Joe Slovo:

A Believing Unbeliever

Joe Slovo, South African Communist Party chief, shatters the preconceptions of the anti-communist media. In many ways he is an uncle-like figure. However, his vast knowledge of politics, worker struggles and Marxist debate leaves one in no doubt where Slovo is ideologically located.

"When I first met Comrade Joe I thought he should be called Oom Joe," observed a young Cape Flats activist shortly after Slovo returned to South Africa from 27 years in exile. "But then as we spoke," continued the youth, "I realised he is Comrade Joe—although not just an ordinary one!" A grey-haired lady who was briefly greeted by Slovo at the event where the youthful comrade encountered his uncle and comrade, was heard to comment: "He's such a nice man, I only wish he wasn't a communist!"

Quiet spoken, Joe Slovo is a warm person, generous with his time. Obviously thoughtful, he is able and willing to speak at length on a number of subjects. Concerned about questions of morality and the source of ethical behaviour, he philosophically discusses the nature of good with all who are willing. As a good Marxist he is keen to stress that the point is not merely to think about the world or even to understand it, but to change it. Convinced that it is possible to have a social order which is kinder and more gentle than that which he has witnessed in the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe or the West, he speaks of the need for a new set of values and ideals in relation to which a better society needs to be built. He has a keen interest in religion and the origins of religious belief, while being eager to explain his secular humanism and materialist understanding of life. As a theologian I was left with the feeling that, despite some differences between us, I was in dialogue with a kindred spirit.

Much of what Slovo says sounds a bit like theology in secular dress. Yet clearly he is operating from a different premise. He has what he calls "a bent for a scientific approach to reality". His case is simply stated: "I cannot present a scientific argument for the non-existence of God, but then neither can I prove the existence of God." Having listened to his views on life, his socialist vision and understanding of religion, I suggest he might be "a kind of believing unbeliever". Thinking for a moment, he responds, "In the sense that I believe in the roots of faith and understand its driving energy, I think that is a pretty neat way of describing me." He shares the vision of communal goodness found in most (all) great religions, while having rejected the metaphysics that constitutes part of the dominant religions of the West.

A Journey Away from Religion

Slovo believes that we are all born atheists. The socialising process does the rest. Raised a Jew in a Lithuanian village ghetto, he was

educated in a school run by the local rabbi. "I had the Bible drummed into my head over and over again." Not sure that he ever fully grasped what the rabbi was getting at, religion provided him with a sense of belonging and self-identity in the face of the anti-Semitism of the time. "This is ultimately what religion is all about," he tells us. "It helps us belong. It gives us a sense of identity. It constitutes a way of dealing with the vicissitudes of life—either by way of escape , as a result of which we systematically destroy the inner resources we have at our disposal to cope with the challenges of life, or by way of encounter through which we develop these resources.

Slovo's mother died shortly after he emigrated to South Africa with his family at the age of nine. He recalls going through the ritual of saying prayers for the dead—the kaddish . Twice a day he prayed in the synagogue in Bellevue, a suburb in Johannesburg, without ever understanding the purpose of these prayers. Slowly, he says, a sense of religious doubt and rebellion began to rise within him. "While other boys were playing football, I harboured an irrational sense of obligation to repeat the same prayers over and over again, while wanting to get on with life by joining the other boys on the sports field. That, I think, is where my religious doubts began. At the time I could not explain my uneasiness about having to pray for the soul of my dead mother, but looking back it was the beginning of the realisation that belief in the afterlife is rooted in a sense of human powerlessness. It is grounded in a simple refusal to accept that life actually ends."

Religion, for Slovo, is a human creation, intended to explain and legitimise humanity's inability to deal with suffering and defeat. This is a theme to which we return. Obviously ready to acknowledge the reality of human limitations, he feels that religion too often reinforces and legitimises human failure, persuading us to capitulate in the face of life's difficulties. Concerned to unleash the more creative and heroic resources within the human psyche which cause us to rebel against evil, triumph over defeat and shape our own future, it is clear that Slovo was forced from an early age to develop these resources in order to enjoy any measure of success in life. Indeed, there is a sense in which Slovo's philosophy of life is a reflection of his own grappling with the meaning of life.

Slovo's father was a truck driver, often unemployed. Compelled to leave school at the age of thirteen the young Joe found employment as a dispatch clerk for a chemist, and soon became drawn into the labour

movement. He joined the Communist Party of South Africa in the 1940s. He later graduated with a BA and an LLB degree from the University of the Witwatersrand, fought in World War ll and became active as a defence lawyer in a number of political trials. He married Ruth First in 1949, and their lives were dominated by the political struggle. He covertly shared in drafting the Freedom Charter although in 1953, under the Suppression of Communism Act, he was banned from attending all gatherings. He remembers the Congress of the People at Kliptown which he observed through a pair of binoculars from the top of a tin roof about a hundred metres away from the square where the meeting took place. In 1956 he was accused of treason—the charges were dropped two years later. He was detained for four months in 1960, became one of the earliest members of Umkhonto we Sizwe (the military wing of the African National Congress) and left the country on a special assignment in June 1963; shortly before the raid on Lilliesleaf Farm in Rivonia near Johannesburg, where other members of the military high command were arrested and jailed for the next 27 years.

A particularly sorrowful memory for Slovo is the price he and Ruth First required their children to pay for the political activities of their parents. "Black children often know massive material deprivation, while white children of parents engaged in resistance," he points out, "experience a different kind of suffering. Black children whose parents rebel against apartheid are regarded as heroes by schoolfriends and neighbours. White kids are shunned. Shaun, Gillian and Robyn (the Slovo children) were told that Ruth and I were traitors, communist filth and liars." He pauses. "Only in recent years have we as a family come to grips with all that happened."

What is the source of his endurance in crisis? Slovo explains that it comes from immersing himself in working for the goals he has set himself. "There will always be suffering in the world," he concedes. Then, seeming to challenge his own observation, he continues: "My goal is to ensure that a society will one day emerge within which hurt will be kept to an absolute minimum and the kind of unnecessary suffering which our children had to face is eradicated from the face of this earth." I ask him about the assassination of his wife who was killed by a parcel bomb explosion in Mozambique in 1982. "The depth of that wound is still with me. I was particularly angry that violence of this kind should be extended to someone who had never been involved in the military." Feeling that there ought to be "a kind of

morality even in war", for a long time he lived with "a great deal of deep, deep sorrow and a degree of bitterness" while being determined not to allow this to shape what he believed his task to be.

I didn't feel that getting the bastards responsible for my wife's death would solve the problem, although I would obviously not have grieved had they been apprehended and dealt with appropriately.

My rational response was to work even harder to ensure that this kind of thing would never happen again. The violence against Ruth was not an isolated case. She was not the only victim of a violent society. I was convinced that the best way to deal with evil was to prevent it from recurring.

Four years later a British court awarded Slovo £25 000 damages against The Star newspaper in Johannesburg for reporting that he had orchestrated the murder of his wife. "This kind of personal attack is what I've found perhaps most painful in life," he allows. Responding to the rumour that he was a colonel in the KGB, his words are decisive: "That is total nonsense. It's an absurd proposition."

My interview with Slovo takes place shortly after his initial treatment for cancer. He speaks of the reality of death. "I am not experiencing any anxiety or grief at present," he says. "I rise to challenges and don't easily quit. If necessary I shall fight the disease. I've still a lot of work to do." He is silent for a while. "I understand from my doctors that my life is probably not going to end too quickly. . . I have had a wonderful life, despite the wounds, suffering and deprivations—and that life must end sooner or later." He insists that the reality of death has not influenced his views on religion.

Is there a Slovo apart from politics? "I am not a single-minded person. I read widely, listen to classical music, enjoy the company of friends and play a bit of poker. The problem with life is that it has a way of setting one's priorities." For him the priorities are clear: Thoughtful political engagement in the South African struggle.

In Quest of the Moral Life

He explains that the reflective life (necessary for creative political work) involves dealing with the competing forces within us. Allowing that morality has to do with integrating the plurality of desires and interests, memories and experiences that constitute one's history, he stresses the need to forge a set of values and principles in relation to which we can work out our response to life. As he sees it, the crises

and events of life continually modify these principles. "There is no ethical absolute or set of ethical rules," he argues, "to which we are simply required to adhere—except the obligation to create a more humane society within which people are taken seriously. And this means firstly a society within which the hungry eat, the naked are clothed and the homeless have houses." He emphasises the importance of recognising that no one tradition, whether religious or secular, has a monopoly on this humanising process. His appeal is for an open society within which we learn to understand and respect the various traditions from which people draw their moral inspiration and values. "When it comes to ethics we need all the help we can get. Instead of trying to impose our values and the source of those values on others, we need to encourage them to give expression to moral beliefs and ideals—then, as we talk together, I am convinced that we will find that the major ethical and religious traditions have more in common than we realise." Arguing that public moral debate in South Africa has been too narrow and parochial, he pleads for a broad-based participation in the creation of a more tolerant and pluralistic culture. "Everyone has the right to share in the quest for a new morality."

He tells the story of his encounter with ds Johan Heyns, the former moderator of the Dutch Reformed Church, at the Peace Conference called in September 1991, in an attempt to put an end to the violence sweeping across the country. "If you do not believe, if you do not have faith, if you have no God hypothesis, what is the source of your morality?" he reports Heyns as asking. Slovo's response was that the most cursory survey of history shows that religion has never been a guarantee of morality or compassion. There were the crusades, the conquest of the Americas by the Conquistadors, Kaiser Wilhelm's troops who marched into World War l with "Gott Mit Uns" emblazoned on their buttons, tyrants who have ruled in the name of Yahweh, Allah and Christ, and apartheid that has been legitimised by Christian Churches.

While insisting that religion is simply not a working hypothesis in his life, he is at the same time ready to concede that the religious memories of his youth have influenced his present ethic (positively and negatively), and that religion as a social phenomenon continues to be a source of interest and stimulation in his ethical reflection. He believes that correctly understood and implemented, the major religions of the world can and ought to play a constructive role in society.

Not the Opiate of the People

Slovo rejects as unMarxian the notion that religion is the opiate of the people. When elevated to the status of a general statement on all religion, the slogan is "unMarxist, because it is undialectical and unscientific," says Slovo. He insists that the anti-religious stance of Marxism on religion emerged as a critique of the specific crimes, committed in the name of a specific kind of religion, which undergirded economic greed and political exploitation. "To the extent," he continues, "that religion distracts the attention of the poor away from the causes of their oppression, by directing their attention to a future reward in heaven, religion is the opium of the people. Marx was correct, religion of this kind is a deadly disease which would better be eradicated from the face of the earth." Slovo is quick to point out, however, that not all religion serves this end. "The majority of the people in South Africa have deep religious roots and the new Constitution must guarantee the fundamental right to believe and practise religion. This must, however, include the right not to believe—without prejudice, suspicion or fear of retribution."

This has implications for the relationship between Church, Mosque, Synagogue and Temple on the one hand and the State on the other. It has special implications for the public promotion and practice of religion, leading Slovo to argue that the compulsory teaching of a specific religion in state schools is as undemocratic a violation of basic human rights, as was the prohibition of religious tuition in schools in Eastern bloc countries. "If religion is taught it must be taught in a nonsectarian manner, designed to expose our children to different religions as well as the various philosophies behind atheism," he says. "In this way mutual understanding and the freedom of choice can thoughtfully be promoted. Freedom is grounded in the availability of information and free discourse." Asked whether he would prefer religion not to be taught in schools, he responds, "I support the teaching of religion comparatively, which means that religious, atheist and agnostic ideas must receive equal attention." This approach to the teaching of religion can, he believes, make an important contribution to a new South Africa.

Many Different Gods

"There are many different religions and gods," Slovo insists. "The God of Trevor Huddleston, Archbishop Tutu, Frank Chikane and others, but also the God of Verwoerd and his cohorts—as well as the

Gods of an array of religionists who use other more subtle ways of subverting the struggle of the oppressed." Showing a particular fascination with the religion of Jesus, Slovo's challenge to the Church is that it return to its origins, relocating itself, like Jesus, on the side of the poor and the marginalised in society. He suggests there is no obvious evidence that Jesus formed a close friendship with any rich person, and that when he addressed himself to the rich it was to inform them that if they wanted to enter the kingdom of heaven they should share their wealth with the poor. "From my perspective," he continues, "the Sermon on the Mount comes very close to a socialist manifesto."

He sees Jesus as a liberation leader in every sense of the term, who resorted to such tactics of struggle as the situation required. Reflecting on the New Testament story, he points out that: "When Jesus' disciples faced danger he advised them to sell their cloaks and buy swords. When hunted by the state Jesus withdrew underground. When entering Jerusalem shortly before his arrest he sought the protection of the masses." Slovo is quite sure: "The religion of Jesus is not an opiate." With a wry smile he adds: "I am no theologian, but wonder whether Jesus would not at least have understood Operation Vula (a covert military contingency plan instituted at the time of the initial talks between the government and the African National Congress) as something demanded by our context."

An Unrehabilitated Utopian

Moving on from Slovo's exegetical forays into the New Testament, his understanding of the human quest for fulfilment is tough but not uncompromising. "Religion teaches us that God made people in His or Her image. That notion needs to be stood on its feet. I believe it is rather the human collective that made God in its image."

He argues that humanity has projected 'into the heavens' what it has not been able to accomplish on earth. The notion of a perfect God and a world to come within which poverty and tyranny are defeated, is for Slovo a manifestation of the sense of human powerlessness that has emerged over the millenniums.

What Marxism has done is take the human longing for the perfect society and incorporate it into a socialist vision. It turns an otherworldy, religious notion into a political programme. Sure there are weaknesses, sometimes called sinful dimensions, to the

human character such as greed and the lust for power. That is partly why democracy is so important. It is an important antidote against tyranny, a dangerous possibility that lies deep within the human spirit. But I also believe in the greatness of the human spirit, the ability of humanity to build a paradise on earth, at least in the sense of putting together a society that is a vast improvement on what is seen in either the capitalist world or the former socialist countries of Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. I am an unrehabilitated utopian, and intend remaining one until the day I die .

If the human race is to conquer the dehumanising aspects of life, a utopian or eschatological vision of what society can and must become is imperative. I reject the metaphysics associated with religious belief, while recognising that the vision of an impending kingdom as described in the Bible and the Qur'an can make an important contribution to politics. Believers must, however, accept the responsibility to translate this vision into political action.

He points to the coalescence of the social visions of true Christians, Jews, Muslims and socialists. "Of course we have all fallen short in translating our visions into practice, but that does not invalidate these visions." He believes that there is a need for religious people to rediscover the moral vision that constitutes the roots of all great religions. Similarly, it is the task of socialists to acknowledge the failure of socialist countries, to return to basics, and ask what the socialist dream means in present historical circumstances. "Without a socialist vision," he argues, "I believe the world will be a poorer place. I say this conscious that the destruction of this vision constitutes the undermining of an important part of what the religious traditions found in South Africa are all about." He concedes that the Eastern European model of socialism has failed. His booklet entitled Has Socialism Failed? indicates that the SACP must commit itself to a multi-party democracy, freedom of speech, thought, the press, movement, residence, conscience, religion and organisation. "To argue," says the unwearying (and provoking) Slovo, "that the socialist vision per se is dead is for the Christian to concede too much. It is to concede that the social vision of the gospel is dead."

I Was Wrong

Slovo was an early critic of the attempted coup against Gorbachev in mid-1991. Why did he take so long to come to the point where he openly condemned the Stalinist practices in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe? What is his response to those who suggest that his earlier silence was a simple matter of political expediency and co-

option? "That's not an easy one to answer. I was wrong." He repeats the question. "Why was I silent?"

I was part of a tradition within the SACP which was historically closely tied to the Comintern (the Communist International in Moscow). . . My engagement, together with that of many others, in the South African struggle included an uncritical 'religious adoration' for the so-called achievements of the socialist world. Today I marvel at the romanticism that characterised that period of my life. There were positive achievements in the Eastern European socialist countries, but the obvious cracks in the system were already beginning to appear. . .

My first uneasiness about Stalinism came when Krushchev revealed a number of atrocities in 1956. . . At the same time I questioned to what extent these crimes were being exaggerated by the imperialist world seeking to destroy what I had convinced myself was a successful workers' state. Then when I and others went into exile in 1963, the Soviet Union and Eastern bloc countries provided us with the only international base from which to pursue our national struggle. That created a natural bias against believing all that was reported in the western media. Living in the Soviet Union also made it extremely difficult, if not impossible to get at the truth behind Krushchev's claims. . . I was also preoccupied with the South African struggle. This was virtually all that mattered to me at the time.

I asked questions, but regarded my energy best spent solely in relation to our own struggle. This was wrong. The level of questioning nevertheless intensified and our party, earlier than most communist parties, began to move away from the basic totalitarian propositions which formed the foundation of the negative features of Stalinism.

Ideological and political isolationism and entrapment is a deadly thing. No one is immune to it. That is why democracy is an essential ingredient of a free society. South African society does not have many democratic, cultural and political memories and/or resources to draw on in this regard. We all need to work hard at this. We dare not again drift into the habits of the past.

Perhaps an Agnostic

What is the source of Slovo's restlessness? Where does his vision and strength to keep striving come from? Explaining my interest (as a theologian) in the transcendent dimension of history, I ask what

draws him forward to what has not been realised in history. Does he have a sense of a transcendent reality in life? His reply is to distinguish between a sense of a transcendent agent and transcendence as a human and historical ideal. "I have a sense of human transcendence. I am driven by the incompleteness of myself and society as a whole. I have a vision of what society can and ought to become, which functions as a lure, continually drawing me into social engagement." Understanding that a believer might personify this dimension of reality as God, Slovo, the non-believer, prefers to leave this reality unnamed. For him this reality occurs as part of a human reality, to be unravelled and explained socially and psychologically. "Above all," he says, "it is a reality which simply must be taken into account in the pursuit of a more complete and better world."

As a historical materialist he is down to earth and practical in talking about what it means to be human. There is at the same time a poetic dimension to Slovo as he speaks about humanity and history. "We are driven. To be human is to reach beyond ourselves to what we ought to become." He argues that there is a sense of incompleteness and a drive for fulfilment within all human beings who take the time to ask what it means to be human, and rejects any suggestion that his sense of vision and inner restlessness make him significantly different from other people. He rejects all talk of being some kind of martyr or hero. "Life," he explains, "is a two-way process. You get out of it what you put into it. To pursue a goal and to be driven by a cause is a glorious and fulfilling thing. When that goal and cause are recognised by global consensus to be right, noble and good, one can only be grateful to have been some small part of it." And what is the nature of that goal? "First and foremost it is a non-racial, non-sexist, democratic South Africa," is his unqualified reply. "The struggle for socialism is a longer-term project. This means that part of my life's vision is hopefully about to be realised, while the struggle for another part of it still lies ahead of me. That's what makes life so exciting and worth living!"

Why he is an atheist? "Because I fundamentally believe our fate is in our own hands rather than being determined by some mysterious force outside of history." I suggest to him that the biblical God is to be found within history—a spirit, a dynamic force; a presence that drives the human soul and history itself towards completion, emancipation and hope. Quick to respond, Slovo insists: "Well, that is pretty close to what I tried to say earlier. My concern is that the human drive for fulfilment be realised in an age of equality, in a situation where

morality and caring for one another are executed in a concrete and practical manner in this world; not in some distant world-to-come. There is, I believe, a certain drive to this kind of fulfilment which is part of the human soul—a notion which I employ in a non-religious sense! Maybe I need to say I am an agnostic rather than an atheist!"

Slovo judges religion, like any other philosophy of life, on the basis of its social function. Does it contribute to the social and political struggle for justice? "Religion in South Africa and elsewhere is today a more ambiguous phenomenon than the kind of religion which Marx knew when he wrote his critique of religion. My interest in religion is partly due to the liberating religious praxis of people whom I have come deeply to respect in the struggle."

"I understand why religious people pray," he says. "Prayer can be an extremely positive dimension in life. It can put people in touch with ideals and values of the humanising process, helping them to reach beyond their prejudices and fears, while enabling them to reach out to one another in the pursuit of goodness. To pray, from my perspective, is to reflect on the purpose and intent of one's engagement in life. Then, to the extent that it leads people to engage in concrete actions designed to further the ends for which they pray, prayer can be an important part of political praxis." Preferring not to get into debate about whether there is someone 'out there' waiting to answer prayer, Slovo is ready to respect the prayers of all people who are seeking to promote peace on earth.

Let's Stop Arguing

Asked to comment on the challenge facing religious institutions in South Africa, his comment is a telling one: "It has something to do with reaffirming their roots. It is to replicate, in the contemporary context, the liberating dimensions which are at the foundation of religious aspirations." He argues that religious people have resented those who have questioned the legitimacy and relevance of religious belief which has deviated from its own most sacred origins, and persecuted those who dared to suggest an alternative approach to life. Marxists, he is equally ready to concede, are guilty of religious persecution that can only be condemned in the strongest terms. "Marxists and religious people owe one another a whole bunch of mea culpas . We actually have a hell of a lot in common."

Slovo is reminded of one of Lenin's more conciliatory comments on religion. "We must stop arguing about whether or not there is a

paradise in heaven. Whatever we may believe about that matter, let's build a paradise on earth." "That's about where I am at," says Slovo. "And should I eventually discover that there is a paradise in heaven, that would be a bonus!"

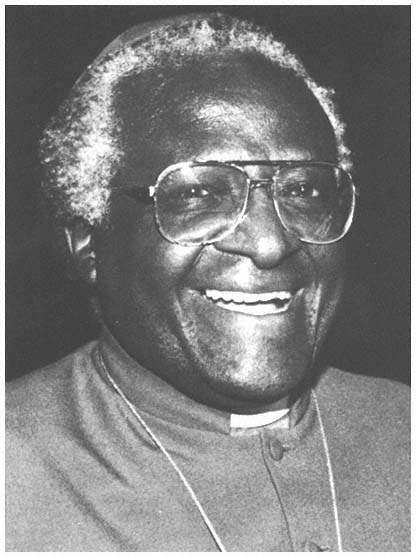

PHOTO ACKNOWLEDGEMENT: South African Chapter,

World Conference on Religion and Peace