19—

Foundations of Political Stability (Book IV)

A Diagrammatic and Prescriptive Paradigm

In an important sense the illustrations for Book IV in B and D (Figs. 64 and 65) continue the theme of stabilizing or neutralizing threats to the body politic inaugurated in the program of Book III, even though they contrast sharply with those of Figures 60 and 61. The allusive and cryptic representational mode chosen for the illustrations of Book III gives way in Book IV to a diagrammatic and prescriptive paradigm that serves as both model and example.

In the opinion of some scholars, Books IV to VI of the Politics provide a practical and unified treatment of the types and subtypes of the six forms of government. Whereas Aristotle examines Kingship and Aristocracy in Book III, in Book IV he analyzes the remaining four: Polity, Tyranny, Oligarchy, and Democracy.[1] Aristotle's discussion is based on his profound knowledge of the historical development and contemporary practice of forms of governments in ancient Greece. Once again Oresme had to translate the verbal concepts and historical context of the Politics into terms and institutions intelligible to his readers. Essential to his task are his selection, definition, and clarification of key terms both verbally and visually.

Styles, Decoration, and Layout of the Illustrations

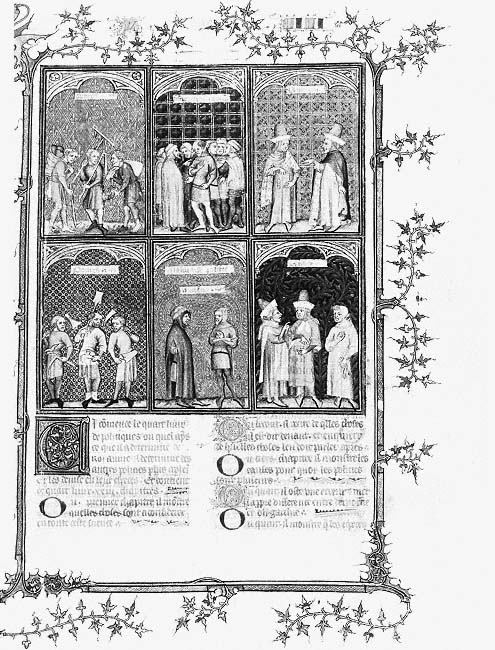

Figure 64 (also Pl. 10) introduces a sequence of four illustrations executed by the Master of Jean de Sy and his workshop. In comparison to the retardataire elegance of the illustrations of the previous two books executed by the Master of the Coronation of Charles VI, the more naturalistic style of the Jean de Sy Master stands out strongly. His ability to give expressive vitality to the poses and gestures of the figures is clearly apparent in the diagrammatic illustration of Book IV. Fluid modeling and subtle alternation of the customary red-blue-green color chord and geometric backgrounds of the three compartments of the upper and lower register both unify and contrast them. A more naturalistic presentation results from eliminating the restrictive quadrilobe enframement of the two preceding illustrations. Instead, the entire miniature and the six individual compartments of Figure 64 are divided by slender gold exterior frames and pink, blue, and white painted interior ones.[2] The figures stand on narrow ground planes beneath rounded gold arches

Figure 64

Above, from left : Povres gens, Bonne policie—Moiens, Riches gens; below, from left : Povres

gens, Mauvaise policie—Moiens; Riches gens. Les politiques d'Aristote MS B.

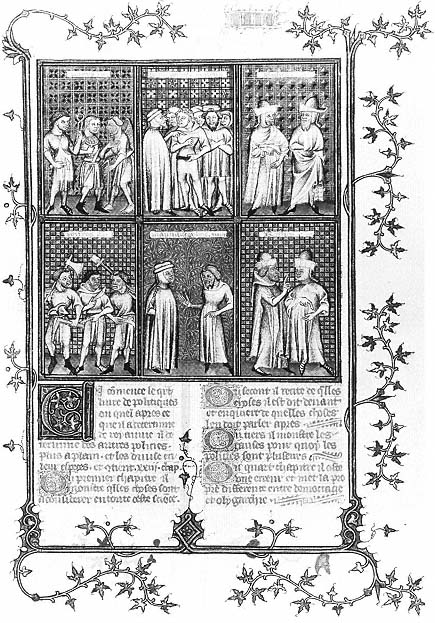

Figure 65

Above, from left: Povres gens, Bonne policie—Moiens, Riches gens; below, from left :

Povres gens, Mauvaise policie—Moiens, Riches gens. Les politiques d'Aristote, MS D.

decorated with corner lozenges and ending in bosses. Together with the frames, this abbreviated architectural element suggests a unified stagelike space in which the six compartments are separate but spatially united in a common structure.

In D the comparable illustration of Book IV (Fig. 65) closely follows the format and layout of Figure 64. The dimensions show a proportional similarity, as each miniature occupies about two-thirds of the folio. In the interests of economy, two major changes have been introduced. The gold arcades of Figure 64 are lacking and the figures are modeled in grisaille. Alternating red and blue geometric backgrounds, green washes, and other touches of color are, however, used for the ground plane and accessories held by the figures. The miniaturist is a member of the workshop of the Master of the Coronation Book of Charles V. Reduction of the modeling of the figures and accentuation of their linear contours emphasize the diagrammatic nature of the program. With their large heads, rigid stances, and exaggerated gestures, the individual forms seem like puppets. The central compartment of the lower register is somewhat marred by the carelessly written inscription that exceeds the allotted space.

The Missing Definition

A last feature missing in Figure 65 is the empty rectangular band in the center space above the frame of Figure 64, where the intended inscription was not inserted. While it is possible that the omission was an oversight, it may also be the case that Oresme may have intended that readers should "fill in the blank" with the word policie .[3] A key term in Aristotle's text derived from the Latin politia, policie is a neologism in French defined by the translator in the glossary of difficult words as a political system, form of government, or constitutional government:

Policie est l'ordenance du gouvernement de toute la communité ou multitude civile. Et policie est l'ordre des princeys ou offices publiques. Et est dit de polis en grec, qu'est multitude ou cité.

(Polity is the arrangement of the government of the whole community or city population. And polity is the arrangement of authority or public offices. And it comes from polis in Greek, which is population or city.)[4]

In addition to this general usage of the term, Oresme employs policie as a synonym for Timocracy, the third of the good forms of government after Kingship and Aristocracy. As Oresme notes in a gloss, Timocracy is used in Book VIII of the Ethics to connote the particular form of constitution in which the multitude rules for the common good.[5] In English, this third form of government is sometimes called a Republic or, more frequently, Polity. Here it seems preferable to use the latter term as a synonym for the more archaic Timocracy.

Oresme's program for Figures 64 and 65 includes both meanings of policie . This double form of visual definition corresponds to the Aristotelian concept of definition as genus and species.[6] In Chapters 12 and 13 of Book IV Aristotle discusses Polity in a specific sense as the third of the good forms. Polity is a mixed constitution: a blend of Oligarchy and Democracy that avoids the extremes of these perverted forms.[7] Furthermore, Aristotle distinguishes between the social class that holds power according to wealth in the bad regimes: the poor rule in Democracy, and the rich in Oligarchy. But the economic group that holds sovereign power in Polity is the middle class. Thus, if the reader supplies the missing word for the inscription in Figure 64 as policie , examination of the headings for Chapters 12 and 13 would lead to definitions of that term. The first title reads: "Ou .xii.e chapitre il determine de une espece de policie appellee par le commun nom policie" (In the twelfth chapter he discusses one kind of government called by the common name of Polity).[8] The next heading states: "Ou .xiii.e chapitre il monstre comme ceste policie doit estre instituee" (In the thirteenth chapter he shows how this Polity must be instituted).[9]

Figures 64 and 65 also refer to the more general use of policie as a system of government. The index of noteworthy subjects offers references to the context of Oresme's terminology under the entry for policie : "La principal condition qui fait toute policie estre bonne en son espece et forte et durable—IV, 15, 16. Et de ce soubz cest mot moiens en richeces " (The basic condition that makes every polity in its individual way good, strong, and lasting—IV, 15, 16. And more about this under the heading moiens en richeches [the mean in wealth]).[10] This cross-reference leads to the entry under that heading:

La principal chose qui fait policie estre tres bonne en son espece et seure et durable est que les citoiens soient moiens sans ce que les uns excedent trop les autres en richeces, mes en proportion moienne. Et tant sunt plus loing de cest moien de tant est la policie moins bonne—IV, 16, 17.

(The principal thing that makes a polity very good of its kind and sure and lasting is that the citizens should be of average means, without some exceeding the others too much in wealth, but proportional to the mean. And the further they are from this mean, the less good is the polity—IV, 16, 17.)[11]

In this context, Oresme refers to Polity not as a specific constitution but as a generic system of government.

Inscriptions and the Index of Noteworthy Subjects

Inscriptions above the central compartments of Figures 64 and 65 lead the reader to further entries in the index of noteworthy subjects relating to the roles of the

classes depicted respectively in the upper and lower registers: bonne policie—moiens (good polity—the middle class) and mauvaise policie—moiens (bad polity—the middle class). Under povres gens (poor people) in the index, two references to Book IV reinforce the message that the poor are less desirable governors than the middle class. Within the same heading a second entry explains: "Comment selon une consideration vraie, ce est inconvenient que aucune partie de la communité ou aucun estat soit simplement de povre gens—IV, 16" (How, according to a valid argument, it is not good that any part of the community or any estate be composed only of poor people).[12]

The linking function of the inscriptions to further explanations in the text continues in the right-hand compartments of the upper and lower registers of Figures 64 and 65. There the word riches leads to four references in the index of noteworthy subjects under the heading of riches gens (rich people). All four entries cite Chapters 12, 16, and 17 of Book IV. The first of two relevant references states that the moderately rich are better than the poor: "Que les riches sunt melleurs que ne sunt les povres, et est a entendre des richeces moiennement—IV, 12."[13] The second says that regimes are more likely to be destroyed by the rich than by the poor: "Que les policies sunt plus destruictes par gens tres riches que par autres—IV, 17."[14] Guided by these intriguing entries, the reader could turn directly to Chapters 16 and 17 of Oresme's translation to follow Aristotle's argument regarding the crucial role of the middle class. One such passage reads:

Et donques appert que la communion ou communication politique qui est par gens moiens est tres bonne, et que les cités politizent bien et ont bonne policie qui sunt teles qu'en elles la plus grande partie ou la plus vaillante ou plus puissante est de gens qui sunt ou moien.

(And thus it appears that the community or political association which is [formed] by the middle class is very good, and that states which work well politically and have a good form of government are those in which the most active or most powerful part is of the middle class.)[15]

The presence of a sizable middle class, then, ensures the political stability of a constitution.

The Visual Structure of the Illustrations

To combine the lexical and indexical functions of the illustrations in a coherent, comprehensible system was no easy task. Although the design of the format reveals complex political, social, and economic relationships, the scheme adopted seems simple and clear. The two-register format conforms to a contrast between good and bad entities on the top and bottom respectively. This type of contrast between opposites is found in Aristotle's writings and "was common in classical, medieval,

and Renaissance logic."[16] The subdivision of each register into three compartments provides further horizontal and vertical comparisons of individual units to each other and to the register as a whole. Position on the left, right, and center also communicates ethical and social oppositions.

Allied to the visual and lexical structure as a means of communicating social contrasts is costume. The clothes worn by the figures in the six compartments signal and reinforce the differences among the social classes in a polity. The long mantles or short pourpoints and tight hose of the middle class in the central compartment are distinguished from the lavish, fur-trimmed robes and high-domed hats of the rich on the right and the short tunics, torn hose, and bare feet of the laboring poor on the left. The poor are also characterized as to occupation and status by their tools.

The number of figures in the various compartments explains key concepts. The most obvious example relates to the contrast between the middle class in Bonne policie above and Mauvaise policie below. In the Good Polity the middle class is represented by a crowd, while in the Bad Polity this group has suffered a severe reduction to two members. The tightly packed central group in Bonne policie engrossed in speech gives the impression of a closely knit body united in a common goal. The circular group of Figure 64 conveys the idea of animated, cooperative communication. By way of contrast, the two figures in the central compartment of the lower register of Figure 65 face each other across a central void that emphasizes their isolation. The treelike form of the background pattern intensifies the effect. In Figure 64 the rich in Mauvaise policie have increased by one third over the two imposing figures of the Bonne policie.[17] The most subtle device of the visual structure of Figures 64 and 65 is the use of the central compartment to signify the mean in relation to physical position, socioeconomic status, and political/ethical orientation. Standing in the center of the composition, the middle class occupies the mean position between the extremes of poverty and wealth.

The clarity of Oresme's program for Book IV contrasts with an illustration in the Morgan Avis au roys that also deals with the middle class as a stabilizing force in the body politic (Fig. 66). A blank for an inscription, like that of Figure 64, occurs in the center of the composition. On the left, a king points with his right hand to the seated figure in the center, representative of the middle class, who counts out the money in his purse. Also pointing to the central figure is the person standing on the right, who may represent a member of the wealthy class. The contrast between the classes, characteristic of the costumes, visual structures, and inscriptions of Figures 64 and 65, remains undeveloped in the Morgan miniature.

The Middle Class and the Aristotelian Concept of the Mean

The placement of the middle class between two extremes in Figures 64 and 65 could remind readers of similar concepts and illustrations in the Ethiques . Of paramount importance is the essential Aristotelian concept of Virtue as a mean be-

Figure 66

Social and Economic Classes of the Kingdom. Avis au roys.

tween too much or too little of a moral quality. Oresme gives stunning visual form to the generic concept in the personification allegories of Book II (Figs. 11 and 12); specific examples occur in the miniatures of Books III and IV of C (Figs. 16 and 21). Oresme makes an interesting analogy between ethical and political character. In a gloss on Chapter 13 of Book IV of the Politiques , the translator explains that Polity (in the sense of a good regime) mixes elements of Oligarchy and Democracy in the same way that Liberality is "composee et moienne de prodigalité et de illiberalité" (composed [of] and [is the] mean [between] Prodigality and Illiberality). Oresme goes on to make the same point about Fortitude: "Et ainsi diroit l'en que la vertu de fortitude est moienne et composée de hardiece et de couardie" (And thus one could say that the virtue of Fortitude is the mean and [is] composed of Courage and Cowardice).[18]

Oresme's association of the middle class with the group that holds the ideal mean position in terms of wealth and political power relates to other key Aristotelian concepts previously explored in the Politiques and other writings. For example, Oresme's commentary on ostracism in Chapter 19 of Book III of the Politiques declares that banishment is an extreme remedy for the concentration of wealth and possessions in the hands of any one group. A wise ruler or regime would avoid such an obvious threat to political stability.[19] Warnings against correct proportional relationships among the members of the body politic is a main theme also of De

moneta .[20] Thus, the illustrations for Book IV continue Oresme's and Aristotle's concern for correct proportional relationships in society and politics. Although ethical considerations play a part in the textual and visual foundations of the predilection for the middle class, in this analysis pragmatic considerations of political utility exercise a preponderant role.

The adjective moiens on the central inscription ties together the complex power relationships among the three groups. Most significant is the mediating political role of the middle class. In Chapter 15 of Oresme's translation the discussion focuses on which form of government is most suitable for the majority of states. The text explains why both the rich and the poor dislike princes. The poor feel oppressed by the central authority of the prince and will carry out machinations against him, while the rich are anxious to obtain power for themselves.[21] But, Oresme states in a gloss, the middle class is free of envy and lives without fear. Furthermore, the gens moiens will not take part in "les seditions et commotions et rebellions" (seditions and disturbances and rebellions) in which the poor and rich participate.[22] Avoiding the extremes of oligarchy when the rich rule or the disorder of the worst types of democracy, the middle class serves as a moderating force in political life. Chapter 16 continues the explanation of how the middle class contributes to political stability. At this point Oresme inserts a lengthy commentary that deals with the unsatisfactory methods of the contemporary church in distributing wealth.[23]

The Ideals of Bonne Policie and Contemporary Historical Experience

The programs of Figures 64 and 65 present Aristotle's generic and specific definitions of polity. Even though costumes differentiate the social classes and their relationships that promote or destroy effective political systems in contemporary terms, the illustrations suggest only a few explicit historical references. For example, representation of the agricultural poor in Bonne policie might have recalled the revolt in 1358 of the Jacquerie. On the other hand, Oresme considers agricultural workers the least politically active and dangerous group.[24] The poor depicted in Mauvaise policie appear to belong to the group of workers who have more leisure for subversive political activity. Their tools identify them as artisans connected with the building trades.[25] In the insurrections of 1358 craftsmen actively opposed the Dauphin. Charles V's mistrust of this group led in 1372 to his regulation of their economic life in Paris by a royal official, the provost of the city.[26]

The presence of the rich might also recall the pressure for a more equitable fiscal system brought about by the financial reforms of 1360, as well as the earlier opposition to the future Charles V of the wealthy merchants and the Parisian haute bourgeoisie led by Etienne Marcel.[27] Yet other contemporary issues addressed in Oresme's commentaries on Book IV, such as the proper distribution of wealth among the classes making up the political community of the church, are not represented in the illustrations.[28] All in all, rather than a subversive plea for establishing Policie as a specific form of government, it seems more appropriate to interpret

the programs of Book IV as general prescriptions for securing effective political rule and avoiding the type of class warfare that leads to political instability. Such a function of the program for the illustrations of Book IV is consistent with its position as the second of a series devoted to the theme of the dangers to, and the means of, preserving political stability within a state. In Figure 64 the abbreviated architectural settings constitute a unified environment suggestive of a spatially related community and memory structure.

Although Figures 64 and 65 fulfill apparently straightforward lexical and indexical functions, their visual structures are in fact quite sophisticated and rare examples in secular iconography of the presentation of such complex concepts of social and political theory. Furthermore, the lucidity of the visual structure reflects and translates Aristotelian methods of argument. Among the most unusual of these devices is the identification of the central area of the pictorial field with the Aristotelian concept of the mean to embrace the ethical, political, and social realms. The allied preference for a triadic ordering scheme promotes understanding and recollection of the central positive and off-center negative opposite qualities. If in oral exposition Oresme was called upon to elaborate on the propositions selected for the illustrations of Book IV, the program he devised would have provided substantive talking points from which his discussion could embark.