17—

Classical Authorities on Political Theory (Book II)

Representations of Classical Theorists

Inasmuch as they relate directly to the content of the specific book before which they appear, the illustrations for Book II in B and D (Figs. 55, 56, and 57) are more typical of the rest of the Politiques cycles than the frontispieces. Yet the programs of Book II reveal a change of strategy in the relationship of image to text. Such a divergence says something about Oresme's limited choices in providing a viable program of illustrations for the text, as well as his judgment about the relevance of its contents for his primary readers.

In Book II of the Politics Aristotle discusses the theories of four ancient writers on the ideal state: Socrates, Plato, Phaleas of Chalcedon, and Hippodamus of Miletus. Following a medieval tradition discussed further below, in Figures 55 and 57 Socrates and Plato are represented together as master and pupil respectively. Although the four thinkers are identified in internal inscriptions, the miniatures offer few clues to their theories. The limited allusions to their writings are handled within the chosen representational mode: portraits of the philosophers. Unlike the frontispieces, in which the lexical functions of the illustrations dominate, these images have an indexical purpose, since they offer a guide to the sequence of authors whose ideas are presented in Book II.

Why did Oresme choose to focus on the thinkers rather than on their thoughts? One reason may be the abstract character of the theories put forward by the four sages. Oresme may have judged that the subjects were too radical or too remote to have any direct, practical application to contemporary problems faced by his readers. Furthermore, it is difficult to conceive of intelligible visual translations of such topics as Plato's "community of wives and children," Phaleas's "proposal for the equalization of property in land," or Hippodamus's plans for developing states according to triads of classes, territory, and laws.[1] Thus, recourse to the ancient iconographic type of the author portrait may have offered the only possible alternative for a visual program.

The Designs of the Miniatures

In B the cryptic and conservative representational mode of the illustration contrasts with the lavish layout of the two folios on which the three portraits are

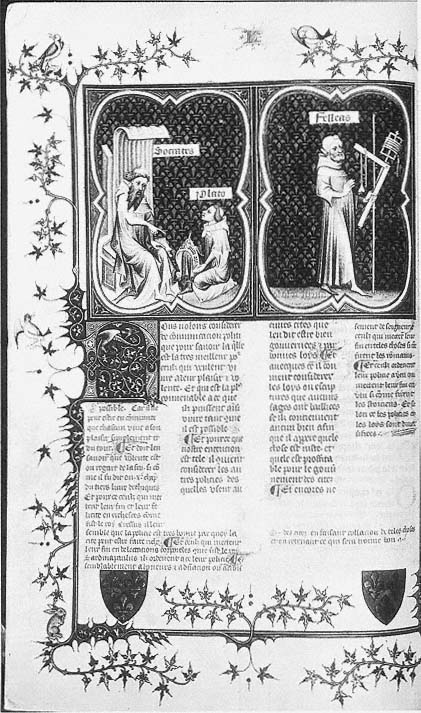

Figure 55

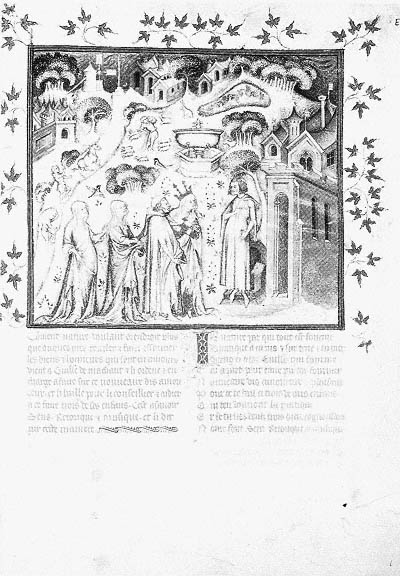

From left : Socrates Dictates to Plato, Phaleas. Les politiques d'Aristote, MS B.

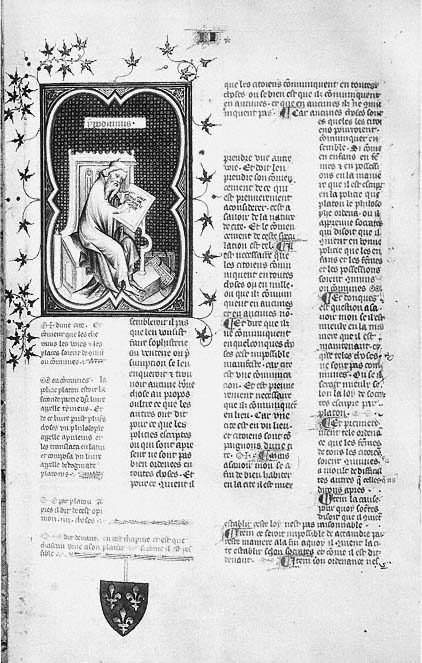

Figure 56

Hippodamus. Les politiques d'Aristote, MS B.

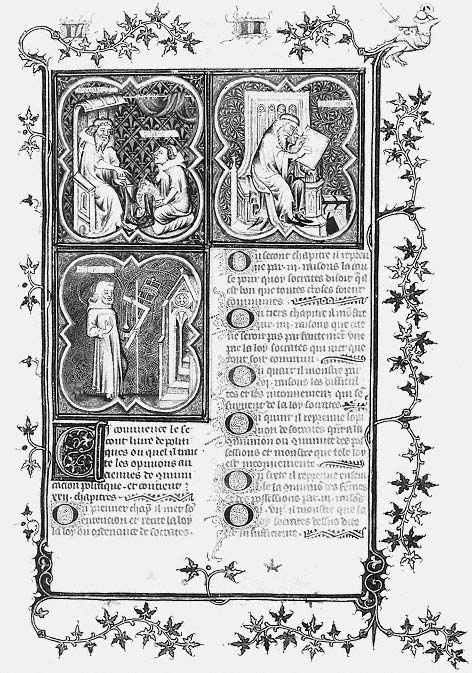

Figure 57

Top, from left : Socrates Dictates to Plato, Hippodamus; bottom : Phaleas. Les politiques

d'Aristote, MS D.

placed (Figs. 55 and 56). Executed by the artist known as the Master of the Coronation of Charles VI, folios 32v and 33 are the most lavish in this deluxe manuscript. For the first time the arms of Charles V (azure shields bearing three fleur-de-lis) appear twice on the lower margin of folio 32v and once on folio 33. Fleur-de-lis also appear as the overall geometric motif in the backgrounds of the miniatures of folio 32v. The decoration of this folio is exceptionally enhanced by the appearance of a rabbit and three birds among the ivy-leaf sprays of the upper and side borders.

All three miniatures are isolated by gold outer and tricolor interior quadrilobe frames. A continuous relationship between the two folios is assured not only by repetition of the shield but also by the alignment and color symmetry of the third miniature on folio 33. A blue-red-blue color scheme unites the layout. Placed after the chapter headings and above the introductory paragraph of Book II, Figures 55 and 56 are distinguished by their large size. The grisaille modeling of the figures, associated in the B cycle with this illuminator, increases their monumentality. The mannered elegance of the master's style, evident in the figures' drapery, hands, and feet, is echoed by the elongated proportions of the quadrilobes. Yet intensity of gesture and expression coexists with the somewhat archaic style. Compatible with the overall design of the folios, both figures and frames contribute to an antinaturalistic effect characteristic of the three miniatures in B executed by this master.

In contrast to the lavish layout of Figures 55 and 56, the illustration for Book II in D (Fig. 57) is more modest. Consistent with the re-editing of this manuscript, the three miniatures have been compressed into a two-register format on a single folio. The first and third exceed the width of the first column of text with which they are aligned. Each miniature is about half the size of its counterpart in B . A member of the workshop of the Master of the Coronation Book of Charles V followed the design of the miniatures of B in the interior quadrilobe frames and the color scheme of the background. The grisaille modeling of the figures in D is a feature characteristic of the entire cycle. As is usually the case in these two manuscripts, the miniatures appear below the running title identifying the book and above the chapter headings and summary paragraph. This order helps the reader to connect the image and its inscriptions with specific information about the contents of the individual book. For example, the general relationship of the images to text occurs in the introductory paragraph: "Cy commence le secont livre de politiques ou quel il traite les opinions anciennes de communication politique et contient .xxii. chapitres" (Here begins the second book of the Politics in which he discusses the ancient theories of political organizations; [it] contains twenty-two chapters).[2] Figures 55 and 56 also provide a linkage between the chapter heading and inscription of each miniature. Thus, Socrates' name occurs in the titles for Chapters 1 to 5 and 7 to 9; Phaleas's in Chapters 11 to 12; and Hippodamus's in Chapters 13 to 14. The normal order of reading the miniatures from upper left to upper right is, however, not observed in Figure 57. Here, the process of consolidating the miniatures on one folio has resulted in an irregular presentation of sequence in the text, where Phaleas is the second, not the last, of the three

thinkers discussed. It is possible, though, that the unusual feature of reading each element of the two-register format as an isolated entity allows a vertical ordering of the miniatures.

Iconography and Invention

As noted above, the well-established tradition of the author portrait serves as the basic iconographic source for two of the three representations of the ancient sages. It is particularly appropriate that this type, which originated in antiquity, should provide the ultimate models for the illustrations.[3] Yet the costumes and furnishings of these classical authorities in Figures 55–57 identify them as medieval teachers and writers. This practice exemplifies Panofsky's principle of disjunction between a classical theme and its medieval pictorial representation.[4]

The images of Socrates and Plato afford an apt example of such medieval interpretations of the conventions of the antique author portrait. One such strain is represented by the type of the Evangelist dictating to a scribe. Socrates sits in a high-backed, canopied chair dictating to the figure of Plato, who kneels at his feet. Each man wears academic dress that identifies him with his status as a "Regent Master of Theology."[5] Among the key elements of the costume is the plain supertunica , with its fur-trimmed hood. Plato's costume also includes two furred lappets on the chest, while Socrates wears a skullcap with an apex. Plato's tonsured head indicates that he is a cleric. Age differentiates the two thinkers: Socrates is depicted as a mature man with a long beard; Plato, as youthful and clean-shaven. The updating of the portrait types by these costumes and accessories places these thinkers within a recognized institutionalized structure for disseminating late medieval thought: the University of Paris. The use of French for the inscriptions identifying Phaleas and Hippodamus and for recording Socrates' ideas affords additional evidence for the authority invested in the vernacular and in French culture particularly.

Plato turns his upraised head, seen in profile, toward Socrates, whose pointing finger conveys the fact that he is speaking (Fig. 55). While listening to Socrates, Plato has written on his scroll the words dictated to him: "soit tout commun" (let everything be [held in] common). The iconography thus conveys the medieval tradition of interpreting Plato as the transmitter of Socrates' ideas rather than as a great thinker in his own right. The miniature also presents the oral communication of knowledge within a teaching situation: the magister cum discipulo relationship.[6] The Socrates-Plato image thus relates to another variation of the medieval author portrait: the writer as teacher, lecturer, or preacher.[7] The rise of universities and the mendicant orders contributed to making such themes popular. In particular, the assimilation of Aristotle's thought into the university curriculum made the depiction of the Philosopher as a teacher a popular theme in historiated initials placed at the beginning of the many Latin translations of his works.[8] A contemporary variation on the theme of the scholar as lecturer occurs in the lower left quadrilobe of Figure 7, the dedication frontispiece of A .

The Socrates-Plato image thus combines two types of the medieval author portrait. But in Figure 55 the inscription on Plato's scroll highlights a particular subject in Book II. The featured text "soit tout commun," highlights the origin in Socrates' teaching of Plato's theory that property and wives should be held in common. Since the text of the Republic was not known in the Middle Ages, it is not surprising that Oresme, referring to a commonality of wives and property, cites the second part of Plato's Timaeus and Apuleius's De dogmate Platonis .[9] The prominence given the words soit tout commun accords with the lengthy discussion of this concept in the text and glosses of the first nine chapters of Book II. The remaining seven chapters of Book II on ancient constitutions are not represented in the program of the miniature. The "soit tout commun" inscription may also highlight what Oresme considered a politically explosive or subversive theme. In the re-edition of D , however, Plato's scroll no longer carries an inscription (Fig. 57). Despite the addition of a curtain to suggest an interior setting, Figure 57 lacks the intensity of expression characteristic of the figures in Figure 55.

In both Figures 55 and 57 Phaleas's (Felleas ) attributes, not words, characterize the theories of this writer. Since his ideas relate to the redistribution of land and property, he is depicted with symbols of measurement. In his left hand he holds a T square on which is draped a length of string weighted on one end. A vertical rod and an unidentified instrument wrapped in string are also depicted. Facing and striding to the right, Phaleas gestures with upraised hand toward these implements. Standing in the middle of the picture field, he appears as an aged figure with a short beard. His plain bonnet and simple mantle, which lacks the fur-trimmed hood that indicates the academic status of Socrates and Plato, suggest a lesser, secular rank. The elongated proportions of his figure, visible especially in his thin feet shod in pointed poulains , are typical of the style of the Master of the Coronation of Charles VI. Although the iconography may derive from the representation of a standing author holding his writings, the figure of Phaleas also recalls the depiction of a sacred person identified by his attributes. Precedents for the appropriation of this scheme occur in the Ethiques illustrations of Justice in A of Book V (Fig. 24) and of Art in Book VI of C (Fig. 34). Phaleas's vertical posture may have been chosen to balance and vary the seated figures on his right and left. Yet the lack of any kind of setting to which Phaleas might relate results in a discordant effect. The addition of a building in D (Fig. 57) may have been an attempt to remedy the lack of a concrete object appropriate for Phaleas's instruments of measure.

Hippodamus of Miletus (Hypodamus ) is the last theorist represented (Figs. 56 and 57). He wears a skullcap similar to that of Socrates. The lack of a fur-trimmed hood on his plain mantle appears to disassociate him from university status. His white hair and long beard suggest advanced age. Facing right, he is seated on a low-backed chair equipped with a stool to which a writing stand is attached (Fig. 57). Next to it lie two upended books. Hippodamus is engaged in writing with pen and scraper on a ruled sheet. Although in Figure 56 it is possible to read individual letters and several words (le and les ), the writer's hands conceal the ensemble. Thus, unlike the images of Socrates and Plato or Phaleas, those of Hip-

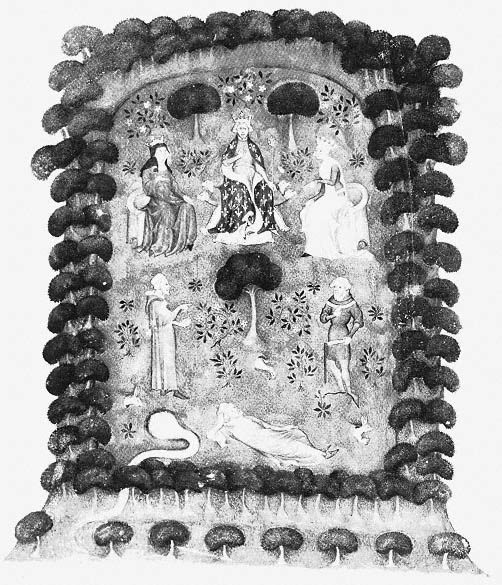

Figure 58

The Dream of the Author. Le songe du vergier.

podamus do not reveal any clue about his ideas. Yet in all three portraits authoritative doctrine and wisdom are embodied in mature, masculine figures characterized by their white hair and beards.

In another sense, however, the attention given to the ancient writers of secular works may signify a shift in attitude toward establishing the notion of individual authorial identity.[10] By means of an inscription or attributes the portraits of Socrates and Plato and Phaleas characterize their works as distinct entities. Placement of the portraits within separate frames further concentrates attention on each one as an individual unit. The inscription of the name within the picture field helps the reader associate the thinker's appearance with the sequential presentation of his theories in Book II. The relationships governing the thinker's name, figure, and activities have indexical and memory functions.

These variations on a theme may well have served Oresme as convenient talking points in an oral explication of Book II. In particular, the Socrates-and-Plato miniature could have easily led to a discussion of the "soit tout commun" subject. Although seemingly remote from contemporary experience, Plato's theories about the commonality of property and wives may have struck a chord with Oresme's primary readers because of the dynastic disputes concerning inheritance of the French throne via the female line. In a similar vein, Phaleas's ideas about redistribution of land had a practical application in view of the protracted struggle with the English about claims to territories in France. Oresme's ability to relate the ideas of the ancient sages to contemporary events is revealed in his long commentary on the issue of voluntary poverty of the clergy, inserted in a refutation of Socrates' views on common ownership of property.[11]

Oresme's long-standing mentor relationship with Charles V and the oral transmission of knowledge exemplified in the Socrates-Plato miniature seem to present appropriate analogues for discussions suggested by the writings of the ancient sages. In visual terms the prominence accorded these secular writers reflects the growth of individual authorial identity. Other contemporary portraits in which the author forms part of a narrative or addresses an audience seem far more adventurous than Figures 55–57 in asserting the writer's identity. The unknown writer of the Songe du vergier , a manuscript commissioned by Charles V in the 1370s, appears in the frontispiece by the Jean de Sy Master as a sleeping figure whose dream unfolds in the discussions of the figures deployed above him (Fig. 58).[12] Also executed by the Jean de Sy Master and also dating from the 1370s is a highly individualized portrait of Guillaume de Machaut in one of two frontispieces of his collected poetic works that shows him introduced to important characters in his writings (Fig. 59).[13] By comparison, the exactly contemporaneous illustrations of the ancient sages in Book II of the Politiques seem almost deliberately archaizing: perhaps the retardataire style of the illuminator of Figures 55 and 56 was an attempt to assert their antiquity.

Oresme's historical interest in classical theories and theorists is consistent with his search for understanding of ancient culture. At the same time, presenting the

Figure 59

Nature Introduces Her Children to the Poet Guillaume de Machaut. Collected

Works of Guillaume de Machaut.

ideas of the ancient sages in the vernacular claims for French culture the means of inheriting, transmitting, and interpreting these authoritative sources. While Figures 55–57 are among the most conservative of the Politiques cycles, their iconographic tradition bestows on the author portraits a new cultural importance.