Félicité Contemplative:

A Monumental Personification Allegory

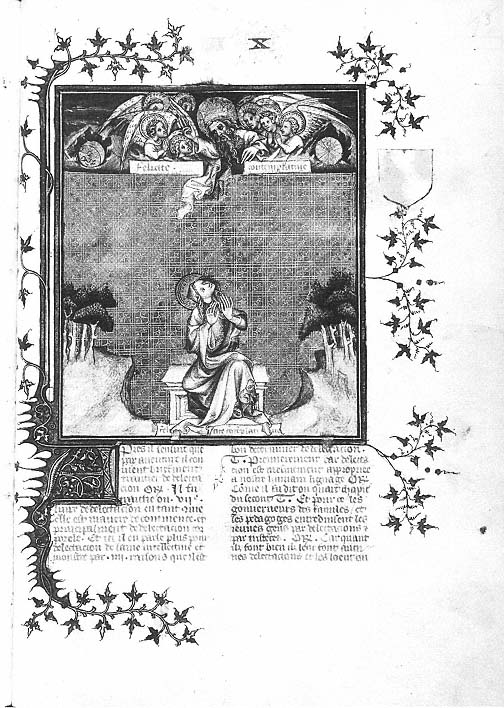

Following the pattern of revising the program of A , Figure 43 (Fig. 43a and Pl. 6) shows certain marked changes in iconography. Like the illustrations for the two preceding books in C (Figs. 38 and 41), the content of the miniature for Book X becomes more specific and focused, even though Figures 42 and 43 share the same representational formula: a seated female figure gazing up at the inhabitants of a celestial sphere. But in Figure 43 a process of simplification brings about not only the elimination of the book and lectern but also of the cloak and beggar. New to Figure 43 is the setting of hills and trees on either side of the principal figure, now identified specifically as Félicité contemplative. Her seat is a low bench similar to that of Sapience in Figure 34. The heavenly contingent has also changed. Instead of the bust-length image of Christ tucked in the corner, the godhead in Figure 43 is a commanding, dynamic force who occupies the center of the heavenly sphere. Accompanied by adoring angels and the sun and moon, he blesses Félicité contemplative. While these iconographic revisions in Figure 43 reveal important alterations in the program of Figure 42, physical and formal features show an even more dramatic character. For one thing, in its size Figure 43 is, after its predecessor

Figure 43

Félicité contemplative. Les éthiques d'Aristote, MS C.

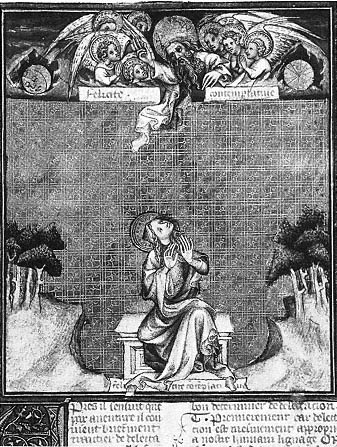

Figure 43A

Detail of Fig. 43

(Fig. 41), the second largest miniature in the cycle. The gold leaves of the outer borders of Figures 41 and 43 suggest another link between them: the execution of the last two miniatures of the C cycle by a separate workshop.

Figure 43, however, shows characteristics that set it apart from the illustration for Book IX. The scale of the figure of Félicité contemplative shows a striving for monumentality unique in the cycle. The care taken to render the drapery folds of her robe and that of the deity is also unusual. Because the figures are modeled in grisaille, their resemblance to, and reliance on, sculptural prototypes seems even more pronounced. The size and beauty of Félicité contemplative, as well as the power of God's head and gesture, mark them as "imagines agentes" or "corporeal similitudes" of ethical ideals.[16] Also distinctive to Figure 43 are the touches of color: green for the clump of trees and blue for the clouds. The use of gold for God's crown, the angels' heads, the sun and moon, and the belt and halo of Félicité contemplative shows the lavish treatment of this illustration.

The extraordinary formal qualities of Figure 43 certainly deserve notice both in themselves and as evidence for the emphasis given to the illustration. Remarkable though it is, the miniature contains a few irregularities that suggest haste or misunderstanding of instructions. Haste is suggested in the blurring of the frame directly above the head of God the Father and above the word delectacion at the lower right. God's flowing drapery, apparently painted over the background, shows evidence of reworking. Inspection of the inscription below the bench of Félicité contemplative also indicates last-minute additions. Compared to the identical words set on either side of God within the usual rectangular boxes, those below Félicité are irregularly shaped and outlined in pen. The use of abbreviations, the small scale of the letters, and the interruptions of words by drapery folds suggest that the lower inscription was added after the upper one. Perhaps Oresme thought that the placement of the higher one confused the reader by identifying the celestial figures with Félicité contemplative rather than with the personification herself. An alternative explanation is that the repetition of the inscriptions affirms the resemblance between the activity taking place in each realm.

Also difficult to interpret is the distance between the head of Félicité contemplative and the celestial sphere. Is the program meant to convey the vast space of an outdoor setting and the separation between the earthly and divine? Or is the miniaturist incapable of locating a monumental figure in a naturalistically conceived space? The too-small trees and rocks indicate a conventional approach to representing a figure in a landscape. Despite these incongruities, the setting signifies that mountains are a traditional location for contemplative activity.[17]

The striving for effects of grandeur in Figure 43 is obvious not only in the composition and the style but also in the expressive quality of the principal actors. Changes from the iconography of Figure 42 noted above also play their part in bringing out characteristics of God and Félicité contemplative inherent in their verbal definition by Aristotle and Oresme. For example, the translator is careful to emphasize that speculative activity takes place in a state of leisure, marked by disengagement from labor, or, in Oresme's words, "repos ou cessacion de labeur ou de occupacions en negoces."[18]Vacacion , the word used by Oresme to describe this state, is a neologism included in the glossary of difficult words at the end of the volume.[19] Oresme also supplies a Christian context for associating the term both as noun and verb with contemplation of the divine. To contrast the active and speculative ways of life, the translator cites St. Augustine as the source of the distinction and the biblical exemplars of the two types of existence:

Ainsi disoit St. Augustin de Marie et de Marthe, que l'une vaquoit et l'autre labouroit. Donques il veult ainsi argüer: Félicité est en vacacion, et les vertus morales ne sont pas en vacacion; mais la speculative, etc.

(Thus spoke St. Augustine of Mary and Martha: one took her rest and the other toiled. Therefore he wishes to argue thus: Happiness lies in leisure, and moral virtues are not passive, but the speculative virtue is, etc.)[20]

In another gloss at the end of Chapter 13, in which the term vacacion is introduced, Oresme again turns to Scripture to emphasize the superiority of the contemplative life: "Et est meilleur que n'est félicité de vie pratique ou active. Et pour ce dit l'Escripture : 'Maria optimam partem elegit, etc.'" (And it is better than the Happiness that comes from the practical or active life. And for this reason Scripture says, "Mary chose the better part").[21] In Figure 43, Félicité contemplative shows no sign of the apparently worldly activity that marks her counterpart in Figure 42.

Other aspects of Félicité contemplative's character absent in Figure 42 emerge in this illustration. The deletion of the cloak-and-beggar motif emphasizes the self-sufficiency or independence of others that constitutes a great advantage of the contemplative life. The large gold halo accorded Félicité contemplative conveys the divine quality of such a mode of life stripped of "passions corporeles" (bodily passions).[22] In a gloss to Chapter 15, Oresme explains that because of Félicité's disregard of such emotions, "elle n'est pas a dire humaine, mais divine" (She is not to be called human, but divine).[23] Her halo also relates her to the inhabitants of the divine realm. Of all the female personifications in the A and C cycles, Félicité contemplative is the only one awarded a sacred status, an honor that refers to the idea that speculative activity expresses within human beings "aucune chose divine" (something divine).[24]

The posture and gesture of Félicité contemplative reveal her character. Unlike the analogous personification in Figure 42, Félicité contemplative no longer needs a book to inspire her activity. With sharply turned head and upraised hands, she glances directly at God and the celestial sphere. Figure 43 emphasizes the meaning of the verb contempler as an act of actually looking at something.[25] Furthermore, the gaze of Félicité contemplative affirms her independence of earthly things and her direct communication with the objects of her contemplation. Since Félicité's activity is based on the intellectual virtue of Theoretical Wisdom (Sapience), which encompasses Intuitive Reason (Entendement) and Knowledge (Science), she seeks to express the best elements encompassed by the human intellect. The act of contemplation, which resembles the activity of divine beings, brings directly to her sight the objects of her speculation.[26] Not surprisingly, the model for Félicité contemplative is the same inspired Evangelist mentioned for the figures of Sapience in the illustrations of Book VI (Figs. 33 and 34).[27]

The gesture of Félicité contemplative may also provide clues about the antecedents and interpretation of the figure. Her eloquently upraised hands may indicate astonishment, submission, striving, or prayer. Stemming from her exalted activity and relationship to the deity, such expressions are appropriate also to personifications of the vita contemplativa . As previously noted, a process of medieval exegesis identified the sisters Martha and Mary of Bethany as exemplars of the vita activa and vita contemplativa respectively.[28] But various medieval writings cite the Virgin Mary as one who unites both categories of experience.[29] Although Oresme does not mention the Virgin in such a context, he may have referred the miniaturist to an image of Mary. The ideal beauty, blue mantle, and long hair of Félicité contemplative are attributes of the Virgin appropriate to such an allusion.

The representation of God the Father also conforms to medieval iconographic tradition.[30] The deity as a creative and unifying force of the cosmos is symbolized by his command of the heavenly host of angels and the depiction of the sun and moon. God's blessing gesture and the fall of his drapery into Félicité's sphere indicate the spiritual affinities between them. As Oresme's text states, of all human activities, the one closest or most like the activity of God is the most blessed.[31]

Although in his discussion of Félicité contemplative, Oresme does not give an explicit Christian definition of God as the object of her activity, it is difficult to say whether he envisioned a philosophical rather than a theological frame of reference. At the point in Chapter 15 where Oresme speaks of the excellence of Félicité contemplative, he refrains from defining her character as a task beyond the scope of the present inquiry. His gloss also evades a clear interpretation: "Car ce appartient a la methaphisique et a la science divine. Mais par ce que dit est, plus excellente que n'est félicité active" (For this belongs to metaphysics and theology. But by what is said, [it is] more excellent than is happiness of the active life).[32] Furthermore, Oresme does not carry on the distinction made by Thomas Aquinas that the contemplative life in this world yields only "imperfect happiness," compared to the "perfect happiness attainable only in the next life consisting principally in the vision of God."[33] The imagery of Figure 43 does not resolve this problem either. Although God is not associated with specifically Christian symbols as in Figure 34, it is hard to imagine that Oresme or his readers understood the text or the image in secular, philosophical terms. Even if Oresme wished to convey such notions, the conceptual and linguistic transformation of the vita contemplativa during the Middle Ages into a Christian context makes such an interpretation difficult. Likewise, the visual associations of Figure 43 are also founded on religious iconography. As is the case with the visual language chosen to represent Justice légale in A (Fig. 24), the illustration of Félicité contemplative has an ambiguous or multivalent character. Yet the absence of overt Christian symbols may furnish a clue to Oresme's perceptions, if not to his audience's reading of them.

The relationship between God and Félicité contemplative also deserves comment. By virtue of his position in the celestial hierarchy, his crown, and his commanding gesture, the image of the deity is the dominant force. It is consistent with Aristotle's outlook that the highest creative and intellectual powers are masculine. Also traditional is the contrasting passivity of Félicité contemplative, a compliant and beautiful young woman. Yet the size, monumentality, and halo of Félicité give her figure visual and spiritual authority. Ironically, the representation by a feminine personification of the highest type of happiness derived from intellectual activity is perhaps the most dramatic instance in the Ethiques cycles of a disjunction between the image and Aristotle's views of female mental, moral, and physical inferiority.