Visual Definitions

The familiar concept of Fortitude or Courage is Fortitudo in Latin; in medieval French the equivalent noun was force . Oresme changed the Latin ending to introduce Fortitude as a neologism.[7] If the reader is unfamiliar with the term included in the inscription of Figure 15, the meaning can be found in the glossary of difficult words supplied by Oresme: "C'est la vertu moral par laquelle l'en se contient et porte deüement et convenablement vers choses terribles en fais de guerre, si comme il appert ou tiers livre; et par especial ou .xvi.e chapitre en glose" (It is the moral strength by which one controls and bears oneself appropriately and fittingly in the face of the terrible events of war, as is revealed in the third book, in particular a gloss of the sixteenth chapter).[8] The titles for Chapters 14 through 21 include the word Fortitude and provide another system for the reader to find locations in the text itself where the inscription of Figure 15 is repeated.

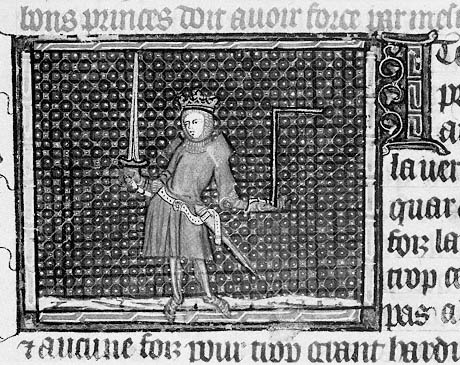

The visual definitions of Fortitude in these two images represent the virtue as male. Such a choice, an acceptable and traditional alternative to the depiction of Fortitude as female, has obvious advantages. First, a masculine Fortitude more naturally associates the sphere of activity of this virtue with conduct on the battlefield, an exclusively male domain. Second, the representation of Fortitude as an armed knight signifies the warrior class, one of the three estates of medieval society. In Figure 15 the addition of a crown to the representation, as well as the conspicuous fleur-de-lis background, specifically associates Fortitude with a virtue possessed by the king of France. A direct precedent for such an identification occurs in an illustration from the Morgan Avis au roys (Fig. 17). In this miniature, the king not only carries a sword but holds a measuring stick, symbolizing reason. The representation is connected with the rubric emphasizing that "bon princes doit avoir force par mesure" (a good prince must possess courage with moderation).[9] Moreover, a subsequent passage identifies Courage (called Force) with "li bon roy de France" (the good king of France).[10] Although Charles V was not an active military leader, Christine de Pizan continues to associate him with the warrior role of French kings.[11]

The forward-moving figure of Fortitude (Fig. 15) is seated on his blue-draped mount and clad in armor. As he advances into battle, his frown and tight grip on his horse's reins, as well as his upright posture, express consciousness of danger. The horse's bent leg and open mouth echo his rider's alert response to approaching danger. A sense of compelling motion is conveyed by the horse's fluttering drapery, which overlaps the quadrilobe frame.

The right half of Figure 15 is occupied by a second cardinal virtue, Actrempance, or Temperance. Oresme defines the nature of Actrempance in Chapter 22: "Or avon nous dit devant que actrempance est moienneresse vers delectacions et les modere" (Now we have said earlier that temperance is the mean [midpoint] in the direction of pleasure and serves to moderate the latter).[12] He elaborates in a sentence from the first gloss in this chapter, which compares Fortitude with

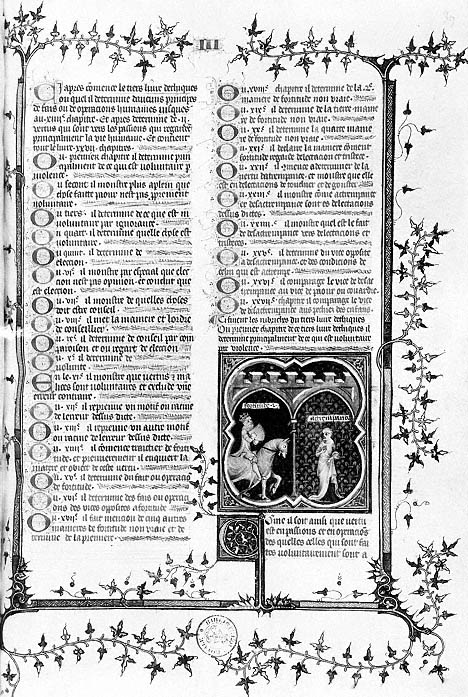

Figure 15

Fortitude, Actrempance. Les éthiques d'Aristote, MS A.

Figure 15A

Detail of Fig. 15

Temperance: "Item, fortitude resgarde les choses qui sont corrumpables de vie humaine. Et actrempance resgarde celles qui la conservent ou en singulier comme boire ou mengier, ou en son espece comme fait ou culpe charnel" (Item, Fortitude concerns things that are capable of corrupting human life. And Temperance concerns those which preserve it either individually, like drinking or eating, or in its species, as in the sin of the flesh).[13] Thus, the pairing of the two virtues not only follows the textual sequence but also presents a contrast for explication by Oresme.

The program for Figure 15 effectively juxtaposes the two virtues. Fortitude looks to the right, Actrempance to the left. The first wears blue garments set against a background of red fleur-de-lis; the second is clad in red and rose set against a dark blue field of the same motif. The traditional female gender of Actrempance, whose wary glance and upraised hand express an appropriate spiritual alertness and restraint, contrasts with the masculine activity and movement of Fortitude. The latter is active and engaged; the former, detached and contemplative. The widowlike wimple worn by Actrempance further accentuates her spiritual character of moderation in respect to bodily pleasures. The miniaturist has imbued the two virtues with expressive qualities consistent with their verbal definitions.

The likeness and difference between Fortitude and Actrempance explained in the gloss cited above also emerge from other aspects of the pictorial design. The two virtues are united in one quadrilobe, but within the common space they inhabit separate rooms,[14] divided by a central column supporting two pointed

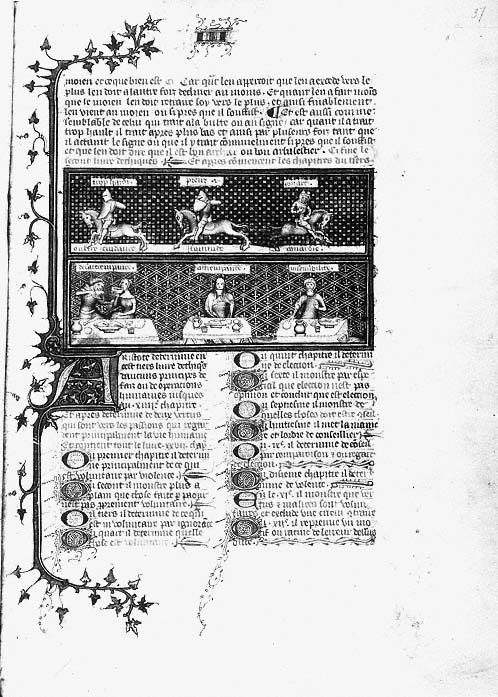

Figure 16

Above, from left : Oultrecuidance, Fortitude, Couardie; below, from left : Désattrempance,

Attrempance, Insensibilité. Les éthiques d'Aristote, MS C.

Figure 16A

Detail of Fig. 16

Figure 17

A French King as an Exemplar of Courage. Avis au roys.

arches. These arches are in turn topped by a rectangular wall segment with a large central spandrel and two smaller ones terminating in a row of seven crenellations. The gray color suggests a stone structure, although its practical function is difficult to determine. Initially this wall, or gateway motif, appears in two miniatures of A beginning with Books III and IV (Figs. 15 and 20) as a means of separating two representations. But in the remaining illustrations of the cycle, except for that of Book VII, the wall is undivided, embracing a single representation. While it is possible to explain the prevalence of the crenellated wall motif as a decorative device, its repetition in the miniatures of A may also have symbolic connotations. In various literary and visual images, personifications of the virtues are often placed within a tower, castle, or city wall setting. The crenellated wall motif here generally connotes a stronghold: a safe or fortified place in which the virtues exist. This tradition is a feature of the medieval iconography of the virtues.[15]

The crenellated wall motif could also function as a memory gateway. As noted earlier, medieval memory treatises stress the usefulness of visual images in fixing in the mind general concepts by associating them with distinctive corporeal forms located within architectural places.[16] The brightly lit crenellated wall and arches of Figure 15 correspond in a general way to the tower or castle gateway inhabited by Lady Memory in Richard de Fournivall's Li bestiaires d'amour (Fig. 18).[17] Set within the gateway under identical pointed arches silhouetted against contrasting backgrounds, stand strikingly opposed figures (Fig. 15). Connected by the inscriptions with verbal concepts, the individualized personifications of Fortitude and Temperance lend themselves to association with the appropriate left or right location within the gateway. The symmetrical division of the crenellated wall by the central column in Figure 15 encourages visual identification of each half of the picture field with the specific personification. Like two painted sculptures, Fortitude presses forward on the left like an equestrian statue, countered on the right by the still, columnar form of Actrempance. Coordinated also with the central vertical division of the quadrilobe, the separate spaces of the two virtues within the memory gateway are identified with distinctive but juxtaposed verbal concepts and visual images. Simple as it appears, the structure of Figure 15 mirrors not only the order of the text but also its spiritual dimensions. The juxtaposition of opposing concepts, reinforced by gender and color contrasts, corresponds also to rhetorical theory.[18]