6—

Virtue as Queen and Mean (Book II)

Definition and Location of a Basic Concept

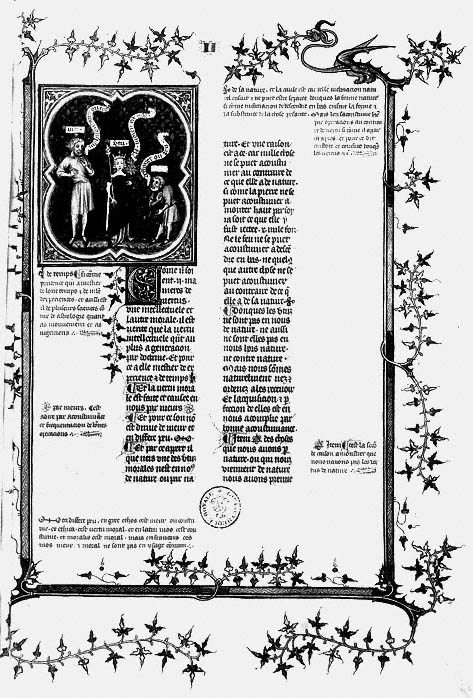

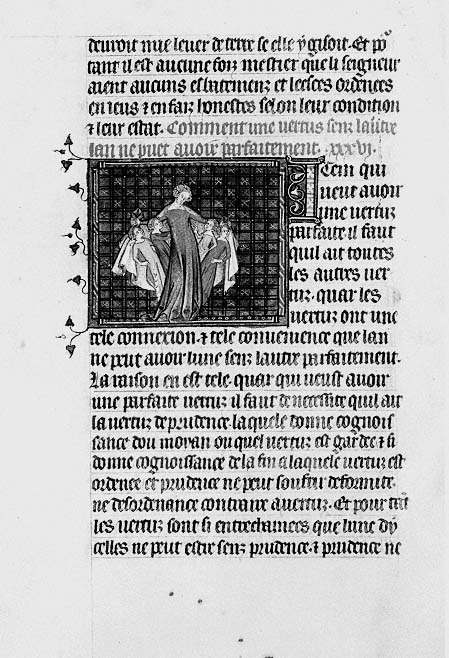

Because the frontispieces of A and C emphasize the dedication portraits rather than the specific contents of Book I, the illustrations for Book II (Figs. 11, 11a and 12, 12a) provide the first representative examples of how the miniatures promote the reader's understanding of the text. Both verbal and visual representations of key concepts in Book II are difficult tasks. Oresme had to make clear in French Aristotle's generic definition of virtue, a principal subject of Book II of the Nicomachean Ethics . Such a definition follows from the discussion in Book I that the goal of human life is Human Happiness, characterized as an activity of the soul in accordance with rationality and virtue. What constitutes virtue (Arete ) or excellence of character is a foundation of Aristotle's ethical thought: "Virtue, then, is a state of character concerned with choice lying in a mean, i.e. the mean relative to us, this being determined by a rational principle, and by that principle by which the man of practical wisdom would determine it."[1] From this generic definition Aristotle proceeds in Books II through V to discuss individual moral virtues. While the familiar four cardinal virtues—Fortitude, Temperance, Justice, and Prudence—figure extensively in Books II through VI, they are not grouped together in any particular order.[2]

Oresme's definition of virtue closely follows the English translation cited above.[3] His translation shows his awareness of Aristotle's method of generic definition by including the French words gerre (genus), diffinicion (definition), and difference in chapter headings and glosses of Book II, as well as in the glossary of difficult words at the end of the volume. Although these words are not neologisms, Oresme seeks to establish their precise logical and philosophical connotations. The emphasis on definition thus relates both to Oresme's rhetorical strategies as a translator and to Aristotelian and scholastic methods of argument. Such efforts also belong to his campaign to make the vernacular an effective instrument of abstract thought. Also included in the glossary is habit , a noun included in the definition.[4]

The importance of the generic definition of virtue in Book II is reflected in the relationship of the illustrations in A and C to the folios on which they appear (Fig. 11, Pl. 2, and Fig. 12). Linked by the Roman numeral II of the running titles to the second book, both miniatures stand at the top of the folio. The miniature in A is the only one in the manuscript linked to the column that has this distinction.[5]

Furthermore, this image is one of the two largest illustrations of the group that spans a single column in A .[6] In both A and C the sprays of the leafy border point to the miniatures. In the same way, below Figures 11 and 12 the large foliated initials of the letter C , embellished with brightly colored leaves and gold accents, draw the eye upward to the illustrations. Special directional emphasis is given to Figure 11 on the upper right margin by the vigorous movement of the dragon drollery.

Plate 2 derives added resonance from the brilliant color of the surrounding verbal and visual elements. The alternating red and blue paraphs, present also in Figure 12, are repeated in the rubrics of the key words in the glosses, the line endings, and the renvois , or symbols linking text and gloss. The vivid red, white, and blue of the elongated quadrilobe frames and surrounding gold lozenges of Plate 2 enliven the peripheries of the miniature. Indeed, the three figures of the A illustration, itself placed symmetrically in relation to the first of two units of text and gloss, receive strategic emphasis by their placement at the points of the quadrilobes.[7] In contrast, the simpler character of C limits the framing and border elements of Figure 12.

In both images, then, the layout of the folios serves as an integrated system of numeric and visual cues that aid the reader's cognitive processes. What other means communicate to the reader the identity and character of the generic definition of virtue? A process of verbal repetition of the key word vertu written on the inscription above the central figure of the A and C miniatures is one important device. This internal text links the words to all but one chapter heading of Book II. Vertu also occurs in the rubrics of Oresme's summary of the book's contents that appear on the preceding folio: "Ci finent les rebriches du secont livre de Ethiques ou il determine de vertu en general" (Here end the rubrics of the second book of the Ethics , where he examines the nature of virtue in general).[8] Placed between the chapter headings and the first paragraph of the text of Book II, the illustrations of A and C function as subject guides to a major theme.

The location of the word vertu leads the reader to Chapters 7 and 8, where Oresme defines the term. Another inscription unfurling on a scroll next to the figure of Virtue reads: "Le moien est ceste" (this is the mean). The heading for Chapter 8 locates the specific place in the text where the two key words of the inscriptions, vertu and moien , are associated: "Ou .viii.e chapitre il monstre encore par autre voie que vertu est ou moien et conclut la diffinicion de vertu" (In the eighth chapter he shows again by another way that virtue is at the midpoint [the mean] and concludes the definition of virtue).[9] In a succinct passage Oresme states the gist of Aristotle's theory of the mean as the moral capacity to respond appropriately in a given situation in respect to action or emotion. Oresme puts it this way:

Donques vertu est habit electif estant ou moien quant a nous par raison determinee ainsi comme le sage la determineroit. Et cest moien est ou milieu de .ii. malices ou vices, desquelles une est selon superhabundance et l'autre selon deffaute. . . . Et vertu fait le moien trouver par raison et eslire par volenté. Et pour ce, selon la diffinicion de vertu, elle est ou milieu ou ou moien.

Figure 11

Superhabondance, Vertu, Deffaute. Les éthiques d'Aristote,

MS A.

Figure 11A

Detail of Fig. 11.

(Thus virtue is a characteristic [habit] involving choosing the mean relative to ourselves determined by a rational principle as the man of wisdom would define it. And this mean is the midpoint between two evils or vices, one of which is conditioned by excess and the other by deficiency. . . . And virtue finds the mean by reason and chooses it by action of the will. And therefore, according to the definition of virtue, it is at the midpoint or mean.)[10]

This passage also makes clear that an appropriate or "mean" response avoids the extremes (the ".ii. malices ou vices") of reactions that are either too great or too small.

Virtue as Queen and Mean in MS A

Following Aristotle's method of generic verbal definition, Oresme's translation clarifies in French essential concepts associated with the terms. At first glance, Figure 11 seems like a labeled diagram in which inscriptions demonstrate the verbal arguments. Yet further study of the miniature reveals unexpected subtleties. To begin with, the personification of Virtue, at the center, seems in no way exceptional. Wearing a crown and holding a scepter in her right hand and a blooming

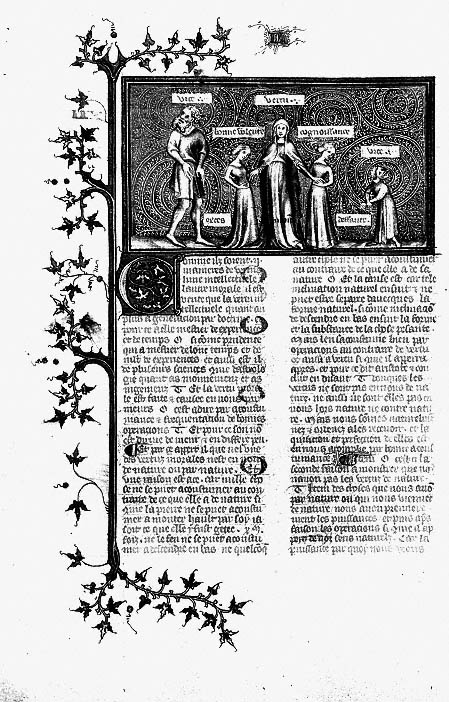

Figure 12

Excès, Bonne volenté, Vertu, Cognoissance, Deffaute. Les éthiques d'Aristote, MS C.

Figure 12A

Detail of Fig. 12

branch in her left, she stands facing the reader. From the inscription stating that the mean is here, it becomes clear that the word moien has a double meaning. Moien refers not only to the moral mean in respect to a proper action or emotional response but also to the center or midpoint of the picture field physically occupied by Vertu.

The scale of her figure is also the mean or norm between the two extremes standing to either side. On the left Excess (Superhabondance) is represented as a youthful, clumsy giant whose gaze is focused ruefully on the tranquil figure of Vertu, an upright vertical accent stabilizing the composition. The rectangular label inscribed Vice identifies him; the scroll next to him characterizes his negative quality as "Superhabondance ou trop" (excess or too much). His abnormally large size visually expresses by means of scale departure from the mean. On the other side of Vertu stands Too Little (Deffaute), personified by the shrunken, aged figure of a hunchback dwarf, whose fault is spelled out on the winding scroll to the left of his head as "deffaute ou peu" (lack or too little). The word vice is absent from the horizontal band above his head. Is this omission an error, or a deliberate attempt to associate the emptiness of the label with moral blankness, the deficiency that the figure embodies? In this case the lack of a sign naming the vice corresponds to the essence of his moral character.[11] Indeed, Aristotle states that many vices have no names, including the one that renders people deficient in regard to pleasure.[12] The diagonal line of descent of the rectangular inscriptions from the height of Superhabondance first to the mean position of Vertu and then to the low point of the empty scroll of Deffaute confirms such a reading. Although it is fitting that this vice is nameless, the adjoining scroll identifies him.[13]

Abstract verbal concepts are vividly expressed not only through scale and position but also through costumes and gestures. Credit for this goes to the Jean de Sy Master, whose lively style imparts a distinctive character to the miniature. The clumsiness of the giant Superhabondance, shown by his outspread right elbow and feet sprawling on the ground plane, suggests a lack of containment that helps define his moral stance. In contrast, the illuminator depicts the pinched, inward movement of the aged, hunched dwarf, emphasized by the feet set closely together. In both instances, posture, age, and gesture indicate moral states: Superhabondance with the excesses of youth, Deffaute with the abstinence of old age. The physical abnormalities of the giant and the dwarf also connote departure from moral norms. Although the vices edge away from the center of the pictorial and—by analogy—the moral field, their gazes are directed to Vertu, embodying the mean. The vivid red of her fashionably cut red robe and the narrow white fur sleeves emphasize her central role. Her gold crown set atop her modishly braided locks as well as the light brown scepter and blooming branch framing her face are distinctive color accents.

Vertu is the only one of the three figures to assume a frontal position. Her placement, reinforced by the vertical points of the quadrilobe, establishes the axial symmetry of the composition and makes visible the notion of holding firm to the moral center. It also signals an ideal status associated with royalty.[14] Representing Virtue as a ruler conveys the generic nature, leadership, and sovereignty of the concept. The association of these positive values suggests the high social status enjoyed by medieval French queens.[15] The prominent, dark red fleur-de-lis background alludes not only to Charles V but also to his consort, Queen Jeanne de Bourbon. In the dedication frontispiece of A , Figure 7, the upper right quadrilobe depicts this queen with a similar fashionable dress and hairstyle.[16]

Vertu's standing as a queen has other social implications. Her embodiment of high moral values is associated with noble and royal status. In contrast, the vices or extremes of Superhabondance and Deffaute are personified by lower-class male figures, identified by their short tunics. This is the first of many instances in the illustrations of the Ethiques and Politiques in which costumes signal to the reader distinctions between socially positive or negative values. Perhaps it is significant, too, that the vices are active male presences whose movements and three-quarter poses stand out sharply from the motionless frontality of the female personification. Ironically, the grotesque vices are endowed by the illuminator with a vitality and individuality completely lacking in the morally ideal figure of Vertu.

The program of this illustration ingeniously clarifies Aristotle's generic verbal definition of Virtue as a mean. In a personification allegory, Oresme's program opposes abstract concepts, a traditional medieval theme and rhetorical device.[17] Employing visual metaphors that effectively juxtapose and distinguish morally positive from morally negative values, Oresme imposes on the personifications an order based on scale and division of the picture field. The visual structure creates analogies between the proportions of the personifications and their deviations

from the moral norm. Superhabondance, a term used in Oresme's text, stands for the generic extreme of Too Much. The vice's position on the left reflects prior sequence in the text definition of this concept. On the right, the smallest figure, Deffaute, is equated with the opposite fault of deficiency. Both Superhabondance and Deffaute are respectively too large or too small in proportion to the mean, personified by Vertu, who stands in the middle of the picture field. While Figure 11 exemplifies a simple demonstration of proportional relationships, Oresme employs it effectively in ordering the visual metaphor. An expert in mathematical theories of ratios and proportions, Oresme provides a more concrete example of his thinking on such topics in the illustration of Book V (Fig. 24). Finally, another ordering principle relates the "off-center" positions of the vices to their moral characters.

With its logical process and ordering of the visual definition, the subtle personification allegory establishes a close relationship between text and image. The discussion thus far establishes conclusively that as master of the text only Oresme could have devised such an ingenious and witty program. Moreover, the translator shows a considerable imagination in clothing the abstract notions of Excess and Deficiency in the compelling guises of a giant and a dwarf respectively. For these actors appear in neither Aristotle's text nor Oresme's. In their creation Oresme may well have intended the image to fix in the reader's mind moral teachings that "are set out in order" by means of "corporeal similitudes."[18] Familiar with Aquinas's thinking on artificial memory, which reflects Aristotle's theories on the subject, Oresme may have consciously sought to have the reader recollect the teachings of the Philosopher by associating them with distinctive visual forms, "imagines agentes —remarkably beautiful, crowned, richly dressed, or remarkably hideous and grotesque."[19] Such a description suits the figures of Vertu and the two vices. Moreover, such "corporeal similitudes" also had the function in scholastic memory treatises of inspiring the beholder to virtuous action. For Charles V, Oresme's primary reader, both the images of Figure 11 and its background would have encouraged his participation in and assimilation of its meanings. The activation of the ground with its large red fleur-de-lis outlined in black allowed the king to "put himself in the picture" by identifying first with the royal symbol and then with the central personification of Virtue.

Oresme's achievement in devising the program of Figure 11 is even more impressive in view of the lack of known precedents. Erwin Panofsky points out that the representation of virtue as a generic concept, totally secular in context, is a landmark in medieval art.[20] Although a miniature in the Morgan Avis au roys representing Vertuz parfaite (Fig. 13) can in some respects claim priority to Figure 11 as a depiction of generic virtue, the opposing vices and the notion of a mean are missing.[21] In any case, the ordering and images of Oresme's ingenious visual definition command admiration for their lively and deceptively simple character successfully realized in the illuminator's inimitable representations of the giant and the dwarf.

Figure 13

Perfect Virtue and Cardinal Virtues. Avis au roys.

Vertu and Her Companions in MS C

The success of the personification allegory in A is shown by the limited revisions made in the equivalent miniature of C . Despite these continuities, both subtle and obvious differences exist between Figure 12 and its model. For one thing, the vertical orientation of Figure 11 in A , dependent on the dimension of the column of text and gloss, gives way in Figure 12 to a horizontally oriented image as wide as the entire text block. Furthermore, the elimination of the interior quadrilobe of the A miniatures permits a freer disposition of the pictorial space. The frontispiece character of this and other miniatures of the C cycle is unique among fourteenth-century illustrated manuscripts of the Ethiques .[22] Perhaps the influential precedents of certain miniatures in B brought about the decision to adopt the frontispiece format for the illustrations of C and D . Whatever the reason, the frontispiece emphasizes the importance of the miniatures. The uniform placement of the miniature serves as a stable, repeated visual cue that associates the summary functions of the image with the beginning of each book. Recognition that the frontispiece offers a more regular and unimpeded field appropriate to the didactic aims of the C cycle may have come from any or all of the people entrusted with the production of the manuscript: the scribe, the translator, the illuminator, or the patron.

The rectangular shape of Figure 12 accommodates two more figures standing on each side of Vertu.[23] The first is identified as Bonne volenté (Desire to Do Good) and the second as Cognoissance (Knowledge). Both are represented as young girls dressed in a simplified type of contemporary costume. They wear gold fillets in their blond hair.[24] Their identical physical appearance suggests that they are twin sisters, matched by analogy in the possession of similar moral qualities. Such metaphors of kinship to express relationships among a "society of concepts" are widely used in the Ethiques programs.[25] The twins' support of Vertu's arms implies that they are her companions, handmaidens, or daughters. Verbal sources accounting for the presence of the twins come from a passage in Oresme's text stating that knowledge of one's actions and the desire to achieve good are essential states of mind for attaining virtuous conduct.[26] The text does not, however, pair these concepts or in any way identify them as twins. Oresme may have invented the kinship metaphor to make more concrete and memorable the psychological states required for excellent or virtuous action.

In accordance with the increased didacticism of the cycles, other changes may reflect Oresme's concern for completeness and consistency of detail. Unlike the case of Figure 11, where the word vice is missing for Deffaute, all the inscriptions in Figure 12 are filled in, placed horizontally, and shortened. Perhaps the change in the Deffaute label suggests that the allusion to deficiency as a moral shortcoming or nameless vice was too subtle. The decision to omit the descriptive scrolls used for the vices in Figure 11 means that the reader must depend solely on visual devices, such as the scale relationships, to grasp the essential character of the personifications. Even Vertu has lost her scroll establishing the association between her and the concept of the mean. Yet after the figure was in place, the scribe,

Raoulet d'Orléans, wrote the word moien on her mantle. The location of the word and the lack of the usual rectangular box framing the inscription suggest an unplanned addition. Oresme may have judged the verbal reinforcement necessary because the increased height of Vertu (relative to Excès) and the presence of the twins may have obscured visual understanding of the concept of the mean.

Figure 12 inaugurates another important change in the C cycle: Vertu is no longer pictured as a queen but is clad in loose, flowing garments and a head covering that combine features of the garb worn by widows and members of female religious communities. Immediate precedents for such costume are found in the representation of certain personifications of the A cycle (Figs. 15, 20, 33, and 35). The dress of Vertu in Figure 12 reflects a long tradition in medieval depictions of both virtues and vices traceable to a tenth-century Psychomachia manuscript. A classical type of female draped figure is the ancestor for such costume.[27] Although the garments of Vertu in Figure 12 do not replicate those of any specific order of nuns or of widows, the costume effectively neutralizes female sexuality. The garb of Vertu also suggests a timeless character, shorn of explicit secular, contemporary, and royal associations created by the costume and attributes of the same personification in Figure 11. In A , two other personifications, Justice and Félicité (Figs. 24 and 42) are also represented as queens, while in C only Félicité humaine (Fig. 10) is depicted as a crowned ruler. Perhaps in the process of revising the program of A , Oresme realized that queenship is not even figuratively a divisible concept. Whatever the reasoning, except for the personifications of Happiness (Figs. 10 and 43) in C , representations of virtues and female vices consistently wear the nunlike garb.

One consequence of this change in costume is the loss of clear social and class distinctions between Vertu and the vices. Yet Figure 12 retains other essential characteristics of the personification allegory established in the A illustration, such as the proportional relationships and ordering of the picture field. Moreover, several nuances of meaning unique to Figure 12 are indeed notable. For example, the inclusion of Bonne volenté and Cognoissance expands the notion of a strong, ethically positive center. The two vices, separated from Vertu and the mean by the twins, are relegated to the sides, or extremes, of the picture space. This distance symbolically embodies the departure from the normative mean demonstrated by the placement of Excès and Deffaute. This effect of physical and moral alienation is enhanced by the way that the vices dramatically turn their heads not toward Vertu (as in Fig. 11) but away from her toward the limits of the picture field, again symbolic of moral extremes. The turning of the heads may relate to the concept that the two extremes are more opposed to each other than they are to the mean.[28] This dynamic movement contrasts with the frontality and stability of Vertu. The gold spirals that animate the warm apricot color of the background emphasize the lively turnings of the vices' heads.

The personifications of Figure 12 stand out effectively against the agitated background, much like actors taking a bow on a narrow stage after the curtain has fallen. The style of the Master of the Coronation of Charles VI (or a member of his shop) lacks the tension and excitement of that of the Jean de Sy Master, who

Figure 14

Vice of Excess, Desire to Do Good, Virtue, Knowledge, and Vice

of Too Little. Les éthiques d'Aristote, Chantilly, Musée Condé.

executed Figure 11. Yet as noted previously, despite the changes in the program, the essential meaning of the personification allegory established in Figure 11 remains intact. Although Vertu is no longer a queen, by scale and position she remains the mean. In comparison, a later fourteenth-century illustration of Book II, based on Figure 12, reverts to the older principle of hieratic scale (Fig. 14), thereby destroying the essence of Oresme's strategy.

Although the integration of the fleur-de-lis background with the lively forms of Figure 11 seems consistent with the royal character of the manuscript, the tranquil and meditative rendering of Figure 12 is also suitable to the more private function of the manuscript as Charles V's reading copy. In short, Figures 11 and 12 are auspicious examples of Oresme's collaboration with miniaturists and scribe to produce images that ingeniously convey complex verbal notions in a lucid and deceptively simple manner.

If Oresme delivered an oral explication, private or public, of the main points of Book II, the illustration of Figure 11 could have served as vital talking points. The visual metaphors of the Giant, Dwarf, and Queen would have made discussion of key points of Aristotle's verbal definitions concrete and vivid, whether or not the illustrations were available or familiar to the audience.