Oresme's Identification of His Readers

Among the valuable information contained in Oresme's prologues to his translations of the Ethics and the Politics is his identification of the readers and the functions of the works.[1] In stressing the universal and historical authority of the works, Oresme insists on the primacy among the Philosopher's writings of these texts.[2] Regarding them as two halves of one work, Oresme describes the Ethics as a "livre de bonnes meurs" (book of good morals), aiding the individual to live the good life, while he designates the Politics as the guide to the "art et science de gouverner royaumes et citéz et toutes communitéz" (the art and science of governing kingdoms and cities and all other communities).[3] The two are interconnected inasmuch as the goal of the political community is to help the citizens to lead the best life defined in the Ethics , while the Politics is concerned with the systematic study of the ideal political community.

In praising God for providing his people with a ruler "plain de si grant sagesce" (full of such great wisdom), Oresme identifies Charles V as the most crucial member of his audience. For, the translator asserts, after the Catholic faith, nothing is more beneficial to the king's subjects than a knowledge of the Ethics , which teaches an individual to be a "bon homme" (good man).[4] Thus, Oresme rightly establishes a context for the translations within the tradition of Mirror of Princes texts: both the Ethics and Politics are deeply concerned with the education of the young and the conduct of rulers.

Oresme's prologue to the Ethiques mentions not only the prince but his counsellors as readers who will profit from study of these works. Since the Politics deals with the science of government, Oresme links knowledge of these texts with the common good: "ceste science appartient par especial et principalment as princes et a leurs conseilliers" (this knowledge concerns first and foremost princes and their counsellors).[5] Oresme goes on to say that the study of all books brings about "affeccion et amour au bien publique, qui est la meilleur qui puisse estre en prince et en ses conseilliers, après l'amour de Dieu" (attachment to and love for the public good, which is the best kind of love a prince and his counsellors could have after the love of God).[6]

In addition, Oresme includes an unnamed group, identified only as "autres" (others), who will also profit by French versions of the Ethics and Politics , since the Latin texts are so difficult to understand:

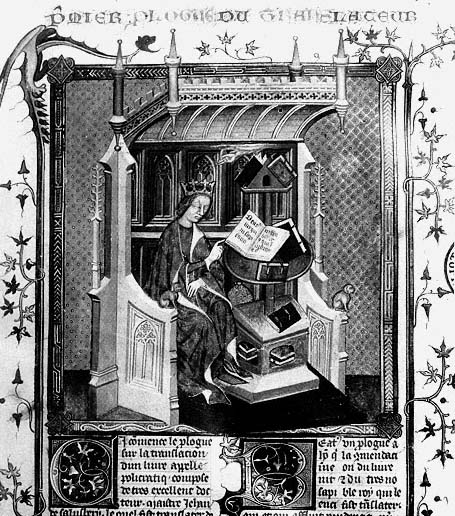

Figure 5

Charles V Reads in His Study. John of Salisbury, Le policratique.

le Roy a voulu, pour le bien commun, faire les translater en françois, afin que il et ses conseilliers et autres les puissent mieulx entendre, mesmement Ethiques et Politiques , desquels, comme dit est, le premier aprent estre bon homme et l'autre estre bon prince.

(The king has desired for the sake of the common good to have them translated into French, so that he and his counsellors and others might better understand them, especially the Ethics and the Politics , of which, as they say, the first teaches one to be a good man and the second, a good prince.)[7]

In short, Oresme identifies his "autres" as persons of influence with little knowledge of Latin. Their understanding of the texts in French translation will benefit the common good. Thus, the moral and social values of the texts make the translations instruments of benevolent public policy. As noted previously, other passages of the Ethiques prologue declare that as these works were transmitted from Greece to Rome, so now they are translated into French. Under enlightened monarchic patronage, the translations of Aristotle's writings form part of a translatio studii directed to an informed circle of French readers.

Throughout the fifteenth century, the subsequent readership of the translations generally belonged to the groups mentioned by Oresme. Later manuscripts of Oresme's translations were owned by members of the royal family, royal counsellors, members of the nobility, and the municipal government of Rouen.[8] Not surprisingly, the number of manuscripts of the Ethiques, Politiques , and Yconomique —with one printed edition by Vérard dating from 1488 to 1489—is relatively small, compared to such popular works as the French versions of Valerius Maximus or Livy. Monfrin cites twenty-one manuscripts of the Ethiques , seventeen of the Politiques , and ten of the Yconomique .[9] Then, as now, the market for scholarly books was limited. The difficult subject matter and the learned nature of Oresme's word-for-word translations and their extensive commentary certainly contributed to their limited popularity. Historical texts with strong narrative threads or anecdotal features obviously had greater appeal as recreational reading than weighty works by the Philosopher. Nevertheless, illustrated copies of the Ethics, Politics , and Economics were not only collected but consulted throughout the fifteenth century.