The Representation of the Wedding Ceremony

The ceremony in front of a church marked the second step in the medieval marriage ceremony. The first was "a betrothal in which one made a marriage promise for the future (sponsalia de futuro ) and the actual wedding itself (sponsalia de praesenti )."[10] The betrothal, which guaranteed arrangements for the transfer of property, was legally binding, as it was based on the mutual consent of the couple. At the church door, the bride and groom expressed their desire to wed and administered the sacrament to one another. The priest's role was that of a witness. Following the ceremony at the church door, the couple entered the building to participate in a nuptial mass.[11]

The ceremony depicted in Figures 83 and 84 obviously corresponds to the second step, the marriage ceremony in facie ecclesiae . In both scenes the groom stands next to the priest and closer to the church door; the leafy spiral of the background in Figure 83 makes clear the separation of bride and groom. The groom places his right hand on his heart in a gesture that may signify a pledge of devotion to the bride, who is not so independent as her intended mate. In both scenes the figure at her left, probably her father, places his hand on her arm, perhaps an allusion to the fact that she leaves the paternal house and protection for that of her husband. The bride in Figure 83 seems to shrink backward in a modest way, as though she is somewhat fearful of the fateful step she undertakes. Her counterpart in Figure 84 appears, however, more forthcoming and removed from her father's protection. This bride is accompanied by a more numerous retinue than that attending her counterpart in Figure 83. Clad in white in both miniatures, the priest holds in his left hand an open book. The book may refer to the appropriate blessings contained in a pontifical or missal or to pledges made by the couple.[12] The lighted taper that the priest holds in his right hand in Figure 83 gives way in Figure 84 to the instrument for asperging the couple with holy water.

Several details of the costume of the bridal couple are worth noting. Following the fashion of the period, the bride wears a low-cut dress decorated with three jewels.[13] In Figure 83 she wears the aumonière , a purse suspended from a belt. This accessory may allude to the marriage custom of offering arrhes , a symbolic gift of coins or jewels relating to the bride's dowry.[14] Both bride and groom wear gold circlets on their heads, possibly suggesting wedding crowns.[15] Several fourteenth-

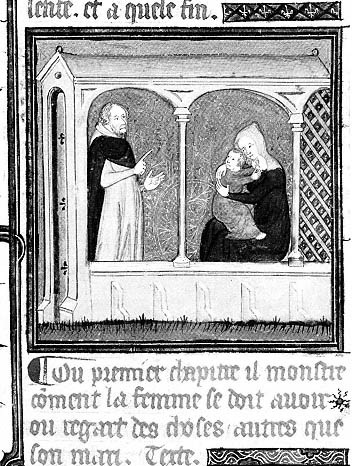

Figure 86

A Husband Instructs His Wife. Le yconomique d'Aristote, Paris,

Bibl. Nat .

century illustrated manuscripts of Gratian's Decretals depict the bride and groom wearing either crowns or circlets in scenes of the wedding banquet following the nuptial mass.[16] Although such circlets were associated with grand attire worn by the aristocracy, such items may have been worn by other classes and were customary for such a festive occasion.[17] In short, the design and details of Figures 83 and 84 may accord with Oresme's intention of encouraging his readers' association of a contemporary wedding ceremony with the discussion of the social and religious institution of marriage in the Yconomique .

Although the text of Book II of the Yconomique continues the patriarchal attitude of Book I, Figures 83 and 84 do not reveal this perspective. As in the illustration of Book VIII of the Ethiques (Fig. 38), the bride and groom are represented

as equals. It is significant that a different passage from Book II was chosen as the subject of the illustration for a slightly later illustrated manuscript of the Yconomique (Fig. 86). Chapter 1 lists six rules by which the wife runs the household under her husband's guidance, while later chapters lay out her obligations to behave properly.[18] Figure 86 represents a husband instructing the wife with a commanding gesture of his right hand. The scene takes place in an arcaded porch or interior of a house. His standing figure occupies one bay; those of his wife and child, the second. She is seated grasping a chubby child, whose expression and clinging gesture indicate alarm about paternal admonitions. The husband's domination is clear from his commanding gesture and standing posture. The wife's submission is equally evident from her seated position and the inclination of her head. Her modest dress also accords with the desired deportment of the chaste and virtuous wife set forth in the text. Also significant is that, as in the illustration of Book I of the Yconomique from this manuscript discussed above (Fig. 82), the husband's costume and the domestic setting indicate the depiction of a middle- or upper-class household. Thus Figures 82 and 86 prefigure the future popularity of the Economics in both vernacular and Latin forms as an authoritative conduct book for regulating family life.[19]

While Oresme's text maintains the patriarchal point of view of the Latin medieval translations, certain of his glosses, such as those in Chapters 4 and 5 of Book II, emphasize the humane character of the husband's treatment of his wife.[20] Although Figures 83 and 84 do not refer to such text passages, they represent a moment of equality in the relationship symbolized by the wedding ceremony. In this way Oresme may have chosen to insert unobtrusively his own progressive views on the companionate nature of marriage. As noted in the previous chapter, in any oral explication of the text by Oresme such ideas could have appealed to and alluded to Charles V and Jeanne de Bourbon as exemplars of the partners in a harmonious marital relationship.