4—

Formal and Political Radicalism in the Short Films of the 1960s

The two short films Machorka-Muff (1962) and The Bridegroom, the Comedienne, and the Pimp (1968) unite in concentrated form the political and formal radicalism for which Straub/Huillet became internationally known by the late 1960s. Machorka-Muff is closely connected to Not Reconciled (1964–1965), which is treated in the next chapter, since both films are based on works by Heinrich Böll. Both Böll films confront the violence of German history and the difficulty of "coming to terms with the past" (Vergangenheitsbewältigung ), combining rage at the continuities with the militaristic and Nazi past, affectionate sorrow at the shame Germany thus brings on itself, and a silent memorial to the victims. Bridegroom couches political rebellion in a concentrated reinvention of film convention and genre that has retained its modernist ability to shock for over twenty-five years. Since it features performances by Rainer Werner Fassbinder and the Action-Theater of Munich, Bridegroom marks the point of intersection between Straub/Huillet and the radical origins of what became the New German Cinema.

Machorka-Muff

In Machorka-Muff , a former Nazi officer enters the West German capital in triumph to lay the cornerstone for the Academy of Military Memories and is welcomed by the political, religious, and aristocratic elites. In interviews, Straub has referred to Machorka-Muff as the story of a rape—the rape of Germany by the military—whereas Not Reconciled is the story of the frustration of violence, since a German rebellion against twentieth-century militarism and Nazism never occurred. Also, he has somewhat facetiously de-

scribed both of them as "Westerns"—Machorka-Muff a Western in the present tense, Not Reconciled a Western in the past tense.[1] The sheriff in Machorka-Muff , however, never rides into town to deal with the gangsters on the screen; "the avenger is in the audience."[2]

The remilitarization of West Germany in the 1950s was Straub's "first political rage," a sign that the country would be prevented from finding its own way out of the wilderness of World War II. For decades he has spoken with compassion for the Germans of the 1950s who were just beginning to have enough to eat after the horrors of the war and were then forced or led to remilitarize. Similarly, Straub is not at all arrogant in regard to the undernourished German film culture of the 1950s and praises the Fritz Lang films produced in West Germany by Artur Brauner.[3] As we have seen, Straub/Huillet thus distance themselves from the contemptuous attitude toward the German public exhibited by the Young German Cinema arising out of the Oberhausen Manifesto, portions of the leftist intelligentsia, and the student movement. As Huillet said regarding student reactions to the Bach film in 1968, "If they laugh when they hear talk of God, they will never make a revolution."[4]

The ability of Straub/Huillet films to provoke both the cultural establishment and rebels in politics and film is indicated by the long and arduous production history of Machorka-Muff and Not Reconciled , begun only after Straub/Huillet were forced to put the Bach project on hold. After meeting Böll to consult him on Bach's language, Straub read Billiards at Half Past Nine and immediately wanted to make a film out of it. This script was also turned down by both Bonn and North Rhine–Westphalia and finally submitted to Rob Houwer, who would have produced the film if Straub had not stubbornly insisted on original sound.[5] Similarly, a producer named Hans Eckelkamp at Atlas-Film, to whom Böll had sent the script for Not Reconciled , might have made the Bach film had Straub accepted Herbert von Karajan as the lead.[6] When Not Reconciled , too, failed to get immediate support, Straub/Huillet developed a scenario based on "Bonn Diary." The association with Schonger, who had been interested in the Bach film as well, failed because of the producer's reservations about the directness of the satire: He was convinced it would simply be banned and his money wasted.[7] Straub went to Eckelkamp at Atlas-Film. While the producer was expressing his reservations about the commercial viability of Not Reconciled , a visitor in his office looked over the scenario for Machorka-Muff , which Straub had also brought along. This visitor, Heiner Braun, eventually played the role of Nettlinger in Not Reconciled . At this meeting, he said he found the scenario amusing and persuaded Eckelkamp to guarantee DM 12,000 for the production of Machorka-Muff . After work began, the producers were persuaded to provide DM 20,000, and the filmmakers raised the remaining DM 11,000 themselves. Since the publisher, Witsch, had not yet acquired the rights to the story, Böll simply gave Straub/Huillet permission to use it for the film.[8]

The difficulties of Machorka-Muff did not end with the financing, however. The producers attempted to interfere with the editing, and the distributor, Atlas-Film, disowned the film after it had been turned down by the Oberhausen Festival. It only got a semiofficial screening after Straub distributed a provocative leaflet at the festival announcing an underground screening.[9] Critics praised the film and condemned its exclusion, but it was only released a year later. Atlas-Film did not pair it with a Western or even with a promising art film like The Silence , as the filmmakers would have preferred, but with a number of less promising titles.[10] Marketing of the film was further hampered by the rating given it by the Filmbewertungsstelle. Since it was rated only "Wertvoll" and not "Besonders Wertvoll," exhibitors received less of a tax credit for showing it than the films with the higher rating. The film was also not approved for holidays or viewers under eighteen years of age. All of this was, of course, intended to hinder the film without appearing to actually censor it. In France, as Straub remarked, it would simply have been banned.[11]

Despite the film's difficult beginnings, Machorka-Muff won Straub/Huillet some renown, including a congratulatory letter from Karlheinz Stockhausen.[12] Buoyed by this, they became even more dedicated to the longer Böll project and decided to produce Not Reconciled themselves. Huillet calculated that they could make two-thirds of the film for DM 50,000, which they would raise themselves in the confidence that the remaining sum could be won on the basis of the finished portion.[13] Godard, Nestler, Huillet's mother, and other friends and relatives helped Straub/Huillet raise the DM 50,000, and the production was furthered by a credit from Walter Kirchner of Neue Filmkunst in Munich, even though it was later withdrawn. The cinematographer from Machorka-Muff , Wendelin Sachtler, had been successful enough to offer to work for free and to lend the blimped Arriflex camera for the film. He later asked for and received his payment of DM 10,000.

After showing the rough cut to Böll, who was less than pleased but indicated they should go ahead and finish, Straub/Huillet took another four months to raise another DM 22,000 and finish the film. Still lacking a distributor, they went with the film to the Berlin Film Festival in July 1965. The film was rejected by the regular festival, but perhaps wishing to avoid the absurd situation of Machorka-Muff at Oberhausen, Enno Patalas of Filmkritik organized a special screening. Announced only by posters saying, "New Narrative Forms in Cinema, Not Reconciled ," the screening became the succès du scandale of the year.

Most of the scandal came from Böll's publisher, Witsch, who had ordered Straub/Huillet to stop work on the film and who now demanded that it be destroyed. Straub/Huillet quickly took the film with them to Switzerland, perhaps to evade this threat, but also—as Straub has insisted was the real reason—to work on the subtitles while staying with a friend.

After much anguished and often bitter debate with Witsch, with Böll uncomfortably caught in the middle, Straub/Huillet won approval to have the film distributed but not to show it on television. Böll, who wanted to avoid all this conflict and concentrate on his work, was eventually worn down by the filmmakers' indignant appeals to his solidarity and his earlier verbal commitment to the project. He finally gave them permission for full distribution but begged in conclusion, "Please don't write me any more such letters!"[14]

The political atmosphere surrounding Machorka-Muff was thus much different from that only a few years later with Bridegroom or Chronicle . The film seems now to be a biting political satire, with strong surrealist elements, and is considered a breakthrough for the German cinema. At the time, however, it seemed too radical to be comprehensible. Straub and Huillet had not been signatories of the Oberhausen Manifesto, and the explanation Straub cites for the film's exclusion from the festival is that they were told, "If we show this film in competition, we will make ourselves look ridiculous—as intellectuals of the Left." "Who? Never heard of them . . ." was Straub's caustic reply.[15]

Another criticism of the film from the Left was that it does not show a "militarist"—in other words, the political satire is not specific enough. This criticism perhaps foreshadows much of the political objection to Straub/Huillet films up to the present day. They are utopian but not specifically connected to current politics and therefore challenging to their friends as well as their foes. Form and politics are important to the seventeen-minute film in roughly equal proportions, perhaps accounting for its continued impact. Reinhold Rauh has chosen it for the subject of two recently published studies, maintaining, "More than in many other films, the few minutes of Machorka-Muff concentrate together film history and film policy/politics."[16] Rauh also considers Machorka-Muff a lone, early precursor of the New German Cinema and, in the period of the Oberhausen Manifesto, "the very first film to seriously propose a new conception of film in the Federal Republic."[17]

The analogy to the Western is useful in considering both the politics and the form of Machorka-Muff . The Böll short story "Bonn Diary" was first published on 15 September 1957, the day of the election that "consecrated" the remilitarization of West Germany.[18] Böll's satire is bitingly antimilitarist, with scathing depictions of army officers whose fame rises with the number of casualties their own forces suffer. Largely avoiding reference to fascism in this dynamic, Böll concentrates on the smooth collusion of aristocracy, church, and military to succeed—"And in a democracy too." "A democracy in which we have the majority of Parliament on our side is a great deal better than a dictatorship."[19]

As in a Western, Machorka-Muff is an evil gunslinger who comes into town and easily takes over because of his villainous reputation. The film does not "act out" this takeover but shows only the confirmation and celebration of the victory. The plot of Böll's "Bonn Diary" follows the events of four days

recorded in diary entries by Erich von Machorka-Muff, a former major in the Nazi Wehrmacht who is to be rehabilitated and promoted to general. Mostly concentrated on the Tuesday after he arrives in the capital on Monday night, the story consists of a number of commemorations of milestones for Machorka-Muff. As the film review by Helmut Färber noted, all of these have been more or less foregone conclusions, and the story thus has both a dreamy quality and an unreal tempo. The events are not occurring as we are told of them, only their public recognition. The ritualistic nature of the scenes depicted implies that, through behind-the-scenes manipulation, history is repeating itself—or continuity is being restored. The film underscores this, beginning with the words on-screen after the title: "No story; a visual, abstract dream."

Peter Nau has also observed that the diary element of the film in the form of the voice-over adds a level of temporal distance to the narration of the Böll text.[20] In the latter, all the action is narrated from the point of view of the author of the diary, looking back in time. In the film, the action is narrated in present tense, while the voice-over, representing a later temporal point of view, comments on it. These comments, Nau asserts, are not blended with the "reality" of the film but are set among the other temporal and dramatic levels of the film in a montage. This he describes, citing Brecht, as a "literarization of film."[21] The film is therefore not an illustration of a text but a construction of cinematic materials. In Nau's words.

The literary text by Böll, the newspaper articles, the music ("A musical Offering" by Bach, the "Transmutations" by François Louis, as well as the song "Once I Had a Comrade," played by a brass choir at the dedication ceremony), the bodies of the actors, their individual manner of speaking, the sound of their voices—these elements go into the film as raw materials and permit, separate from one another, not blended together, the insight into its construction.[22]

The central event described in Böll's text is Machorka-Muff's triumphal entry into Bonn, the capital city of the Federal Republic of Germany, for the laying of the cornerstone of the Academy of Military Memories, the creation of which had been a dream of his youth. Another victory consists in the major's formal recommissioning at the rank of general. Before the cornerstone ceremony, he is visited by a government minister, who greets him as "General" and presents him matter-of-factly with the documents of his commission. A third event in the story is the grotesque revisionist rehabilitation of General Hurlanger-Hiss, after whom the academy is to be named. Legitimized by unpublicized research by Machorka-Muff's fiancée, Inn, this event is enacted by way of Machorka-Muff's reading of the speech containing the new information on war casualties. Finally, the denouement of the story consists of two steps, each conveyed in a very short diary entry for Wednesday and Thursday. On Wednesday, possibly carried away by the emotions of his military success,

Machorka-Muff becomes engaged to Inn (Inniga von Zaster-Pehnuntz: All the cronies of Machorka-Muff bear absurd, usually alliterated aristocratic-sounding German names). The Church, in the person of a priest, immediately sanctions this union of military and aristocracy by annulling Inn's previous seven marriages (as civil ceremonies).[23] On Thursday, Machorka-Muff mentions an "annoying interlude"—the intrusion of political discord into his dream of success. The opposition has complained about the academy project, and Machorka-Muff responds in astonishment, "Opposition? What's that?" The response of the military man reveals that politics is anathema to him and disrupts his project of reconstructing historical memory: "Opposition—a strange word, I don't like it at all; it is such a grim reminder of times that I thought were over and done with."[24] This resistance to the intrusion of conflict and memory that is uncomfortable for Machorka-Muff is actually a last reference to a theme that occurs throughout the "Bonn Diary" and in Billiards at Half Past Nine as well. Machorka-Muff's project in creating his academy is repeatedly couched in terms of reconstructing memory and history, and the language of the story calls attention to this: In addition to the name and purpose of the academy, there is also the Latin inscription Machorka-Muff proposes, Memoria Dextera Est, and the title of his first lecture, given on the last day of the diary, "Reminiscence as a Historical Duty." The type of memory that Machorka-Muff supports is that which leads to the construction of institutions of state power. Military memoirs are less important than the stone building where they are to be written—in Böll's words, "through conversations with old comrades and cooperation with the Ministry's Department of Military History." The political power this represents is more important than the building: "My own feeling is that a six-week course should suffice, but Parliament was willing to subsidize a three-month course."[25]

The element of class is also included in the role that memory plays. For the powerful, memory is a justification for building monuments to their power, but for the less powerful, it merely signifies sentimentality and comradeship. This is made clear by the contrast between the reminiscences of Machorka-Muff's first visitor in Bonn, his former adjutant, Heffling, and Machorka-Muff's mental observations while he is speaking. The diary does not report the reminiscences the two men of unequal rank share, apart from the introductory words, "Remember the time at Schwichi-Schwaloche, the ninth . . .?" (Which are implied to come from Heffling and in the film explicitly do so.) It does contain, however, Machorka-Muff's distracted comment, "It is heartwarming to observe how powerless the vagaries of fashion are to corrode the wholesome spirit of the people: the homespun virtues, the hearty male laugh, and the never-failing readiness to share a good dirty story are still to be found. While Heffling was telling me some variations on the familiar subject, I noticed Murcks-Maloche had entered the lobby."[26] Since an important comrade in the plans for the academy has arrived, Machorka-Muff merely glances at his watch

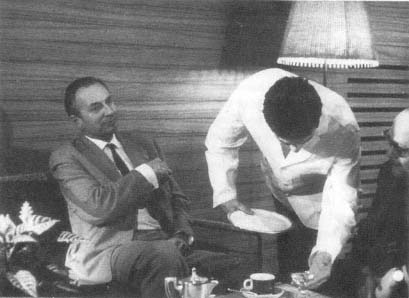

Machorka-Muff (Erich Kuby) in civilian clothes. Courtesy New Yorker Films.

and "with the sound instincts of the simple man he [Heffling] understood immediately that he had to leave."[27] Time is in the control of the powerful, as is memory. The only activity, along with the brief dialogue, in this scene is the ordering of drinks, and this, too, is a marker of status. For his subordinate, Machorka-Muff orders a double schnapps; for Murcks-Maloche and himself, he orders two Henneseys.

The film's adaptation of these actions is one of three departures from the temporal content of the story, and, in each case, the effect is consistent with the domination of time that Machorka-Muff is in the process of enacting. The insignificance of the subordinate's reminiscences and Machorka-Muff's class superiority are conveyed by the camera. It does not remain with the conversation but instead follows the major's order for the double schnapps, waiting over fifty seconds for the drink to be poured and brought. It is the power of the military man's order that "acts." When the schnapps is brought, the conversation is begun and concluded in a matter of seconds. The second conversation, with a powerful comrade, does take place while the drinks are brought and concludes with a close-up of the cognac glasses raised in a toast.

The power to control time and memory is thus inscribed in the film sequences that follow the effects of Machorka-Muff's whims: the securing of a drink, the idle browsing in a newspaper (which actually provides a concentrated survey of the advancing remilitarization of Germany with Christian Democrat

support), and an idle walk through the city. The time in each case may be irritatingly empty to the audience, since it is not accompanied by narratively introduced memories, but in each case, they provide evidence of the time and memories that this character proposes to possess.

Machorka-Muff's domination over time is contrasted in the story with a number of terms that make him seem dreamy and swept away with emotions in response to the magnitude of his successes. The word ergriffen (moved, deeply stirred) is one of the most frequent in the story, and other phrases invoke Machorka-Muff's physical and emotional swooning at what is transpiring: "abandoning myself wholly," "resigned myself with a sigh," "I was too moved to undertake any serious business that morning," "melancholy overtook me," "I got out of bed, followed her in a kind of daze," "I must have swayed for a moment and suppressed a few tears."[28] This dreamy attitude corresponds to the reminders present in the story that there is no suspense here, that all that is happening is a restoration of a past order. When Murcks-Maloche tells him of the success of the plan for the academy, which of course he already knew, he turns it into a kind of military ceremony: "I felt constrained to stand up; I was filled with solemn pride; historic moments have always moved me deeply."[29] In the film, this scene ends with the ceremonious clink of the brandy glasses.

An ironic counterpart to this swoon over a consummation that is nothing new comes after his decision to marry Inn. Both are in a gay mood, as Machorka-Muff observes, "Inna was elated, I had never seen her quite like that. 'I always feel like this,' she said, 'when I am a bride.'" Machorka-Muff's emotions are stimulated by the sensation of power, and his enjoyment of power is never far removed from a sensation of lust. For instance, his engagement to Inn (whose family was only ennobled two days before the kaiser abdicated) is stimulated by "military memories," and his proposal is even couched in terms of his own military rank: "I felt encouraged when she whispered (in church) that she recognized a colonel as her second husband, a lieutenant-colonel as her fifth, and a captain as her sixth. 'And your eighth,' I whispered in her ear, 'will be a general.'" Machorka-Muff's daydreams about the Academy of Military Memories are also punctuated by sexual fantasies. While preparing for a "rendezvous with Inn," he muses that she would be the right wife for him, despite their differing religious backgrounds. Böll does not describe their rendezvous and copulation but rather Machorka-Muff's musings, which connect war and sex: "all the same, the numbers link us together symbolically: she has been divorced seven times, I have been wounded seven times. Inna!! I still can't get used to being kissed on the street. . . . Inna woke me at 617 hours." The sexual intercourse that occurs in the space of Böll's ellipsis is referred to twice in Machorka-Muff's memories in the next few minutes, as his attention goes back and forth between her and the Hurlanger-Hiss files she has prepared for his speech. "Lost in daydreams of her gift of love, I heard

the band music: melancholy overtook me, for, like all the other experiences of this day, to listen to this music in civilian clothes was truly an ordeal." And one of the events was sexual intercourse. The arrival of the minister of defense, to which he also responds dreamily, is also scintillating because it occurs near "the rumpled bed in all its delightful disarray of love."[30]

The nearness of power and sex in Machorka-Muff's consciousness becomes even clearer in his two references to the pleasure or diversion that military officers can get from working-class women. The first instance occurs when his subordinate Heffling invites Machorka-Muff to come and visit sometime, saying, "My wife would be delighted." Machorka-Muff's commentary: "And I promised Heffling I would come and see him. Perhaps an opportunity would offer for a little adventure with his wife; every now and again I feel the urge to partake of the husky eroticism of the lower classes, and one never knows what arrows Cupid may be holding in store in his quiver."[31] The second such reference to sexual exploitation has an even more explicit relation to violence and "military memories." It is an unrealized part of his plan for the academy: "I was also thinking of having a few healthy working-class girls housed in a special wing, to sweeten the evening leisure hours of the comrades who are plagued with memories."[32] Obviously, these memories will not be of the sort to be included in the memoirs the officers are to institutionalize. The film includes in voice-over the first of these comments but excludes the second and the inscriptions Machorka-Muff plans for the portals of the academy: Memoria Dextera Est; Balneum Et Amor Martis Decor.

The sexual aspect of Machorka-Muff's conquest of the capital city is still implied in Straub's description of the story as a rape. The cultural form that this rape of Germany takes is to be that of monuments and institutions. Here, both the story and the film introduce a theme that is significant to all Straub/Huillet films, the difference between monument and memory. Again, Machorka-Muff provides a useful contrast to Not Reconciled , which is about the destruction of monuments in order to reawaken memory. Here, the laying of a cornerstone, dedicated to "military memories," is celebrated. It is to be a place where military officers from the rank of major up can gather to write their memoirs.

The treatment of history that will be introduced here becomes obvious in the dedication speech by Machorka-Muff: He "corrects" the supposedly shameful record of Field Marshal Emil von Hurlanger-Hiss, who had reportedly lost only 8,500 men in the retreat from Schwichi-Schwaloche, when, "according to the calculations of [Hitler's] specialists in retreat . . . his army should, with the proper fighting spirit, have had a loss of 12,300 men." Machorka-Muff reveals with satisfaction that the losses can now be established at 14,700 dead.[33]

This scene, which Nau terms the "satirical high point of the film," is given a special status by its striking cinematic construction. The general's speech

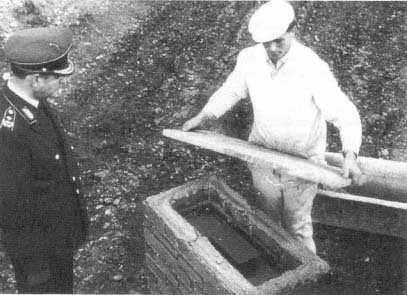

Machorka-Muff (Erich Kuby) back in uniform. Courtesy New Yorker Films.

dedicating the Academy of Military Memories is filmed from above so that emphasis is placed on the cornerstone, his gloved hands holding the papers, the lapels of his uniform, and his cap. From this high angle, the camera tracks in, so that first the papers, then the decorated visor of the uniform cap grow larger. In the process, the eyes recede and eventually disappear except for the suggestion of a fold of skin. The nose and moving mouth—he is a "mouthpiece" after all—become the only signs of his bodily presence. Because of the dramatic effect of this tracking shot, critics misinterpreted it as a series of close-ups, isolating individual aspects. But the continuity of the shot increases the shock of the close-up that does conclude the speech. As the "honorable" figure of 14,700 casualties is named, the camera drops to a low-angle close-up of the fully "exposed" face of the officer, who then steps away leaving the camera to dwell on the empty gray sky. After the brass band plays, the high-angle shot is repeated, showing the mason laying the cover on the cornerstone and Machorka-Muff ceremoniously tapping it down with a hammer.

This visual isolation of Machorka-Muff from his surroundings exaggerates his identification with his role at that moment, as indicated by the gloves, the uniform, and the pages of his speech. It also reduces and concentrates the visual image as his speech becomes most grotesque: He measures heroism by senseless loss of life, evokes continuity of Hitler (with the cozy familiarity of the nickname Tapir) as an authority, and bemoans the ludicrous "disgrace" that

Laying the cornerstone of the Academy for Military

Memories in Machorka-Muff. Courtesy New Yorker Films.

Hurlanger-Hiss suffered—punitive transfer to Biarritz where he died of food poisoning after eating lobster.

The surprising angle of the shot, the point of view that is only that of the camera, not of any possible character or theatrical audience, also concentrates the cinematic nature of such shots. Nau sums up the production of meaning through this separation of elements.

The speech is reproduced intact, but the speaker is captured from various, fragmentary and unusual perspectives. Therefore no reality effect is produced, resting on image and sound doubling each other so as to produce an illusion of reality. Instead of giving the appearance of the film reflecting a reality outside itself, the sequence of the dedication ceremony is only to be seen as a specifically filmic reality, so that in each moment it conveys the explicit expression of the film.[34]

Eric Rentschler places this concentration of filmic reality into historical context in his discussion of the song "I Once Had a Comrade," New German Cinema, and U.S. president Ronald Reagan's controversial visit to the Bitburg military cemetery in 1985. Rentschler notes that the music begins over a shot of the "empty" sky after the speech and the laying of the cornerstone: "We become able to see the music, to read its importance in this setting, to reflect

on the meaning of this song and the tradition it implies, a tradition the Academy for Military Memories means to restore, a legacy that Straub/Huillet every bit as forcefully want to undermine."[35] The cinematic form thus allows "sound to have space to step into the image"[36] and "involves the spectator in the construction, providing space to see through the historical fiction presented here."[37]

Three types of narration are used in the film to convey Böll's satire. Nau pointed out the contrasting moods of two of them: the voice-over narration of the diary and the abrupt intrusions of the dramatized passages. A third, the documentary, will be examined presently.

The narration provided by the diary entries is at times illustrated or acted out by the film. The contrast between the film images and the ironic, short commentary of Machorka-Muff is, if anything, more effective than the story's form. Rather than being embedded in his musings, the comments conclude and set off the meaning of visual sequences. For instance, his dream on his first night in the capital is seen in the film. In the story, he reports seeing hundreds of pedestals with shrouded statues on them, which reveal countless images of himself in uniform bowing in acknowledgment as the shrouds are removed. He touches the pedestal that bears his own name. In the film, we see Machorka-Muff asleep and then the dream images, reduced to three shrouded figures arranged at an angle rising to the right, accompanied by organ music (Bach). The three figures bow when the shroud is removed, and he touches his own name on the pedestal. But it is only in the next shot, when he is shaving, that we hear the self-satisfied commentary of the diary: "Such dreams one only has in the capital." Such a comment resonates with other points in the diaries, where Machorka-Muff says things like "Only in uniform can one . . ." and each of these illustrates the relish with which he enjoys his rediscovered power.

The film departs from the text in its depiction of the walk Machorka-Muff takes through the city because he is too restless and "ergriffen" to undertake anything serious. The film excludes his comment, "Although I was in civilians, I had the impression of a sword dangling at my side; there are some sensations which are really only appropriate when one is in uniform."[38] The film does connect the uniform with erotic thrills as it is revealed to Machorka-Muff, however, with wildly rapid close-ups alternating between the uniform, Inn's face, and his leering expression. The film replaces this sensuous relish of walking through the city, armed and in uniform, with several shots following Machorka-Muff after the voice-over simply states, "After Murcks had driven to the ministry, I wandered through the city." The relation of the Western gunslinger to the town he is taking over is suggested by the shots that follow. Böll's text stresses the physical side of Machorka-Muff's feelings as he walks, and Nau has noted how the film undertakes a brechtian "literarization" of film by placing the temporal and physical elements of narration next to each other

so that their narrative structure is revealed after they have been presented, rather than implied beforehand and then fulfilled.[39]

The meaning of the walk through the city emerges only after it has taken place. Since Straub gave the film the "formula" M = M and connected it to other gangster films, Fritz Lang's M is suggested when the murderer sees images in shop windows reflecting his own psychological obsessions. First, Machorka-Muff is shown crossing streets and plazas. He looks at the shop window of a pharmacy with the picture of a very old man next to a mechanical figure that does gymnastics on a bar. In the lower left of the window is the slogan "To grow old—to remain young, that is the wish of us all." He then picks up a visiting card on the steps of a Chinese restaurant. The card, addressed to "Chérie," appears to be an invitation to a sexual encounter, with a meeting at a club called the Queen of Spades, in the Nymphenburger Strasse. Another possible reference to M is the cry of a young girl, "Mummy, the lights are going on!" as the major walks along the streets. A second shop window shows women's fashions in the military style of the Hussars.

Finally, the camera makes a 180-degree pan over the Rhine and the suburbs behind it, ultimately stopping with a bridge in the background and Machorka-Muff in profile filling the left side of the screen. At this point, he shifts from his anticipation of his fiancée to memories of his old general. The voice-over accompanying this panorama is, "Uplifted by the certainty that my plan had become reality—once again I had every reason to recall one of Schnomm's expressions: 'Macho, Macho,' he used to say, 'you've always got your head in the clouds.' He had said it when there were only thirteen men left in my regiment and I had four of those men shot for mutiny."[40]

The sexual anticipation that Böll's text juxtaposes with the military memories and the anticipation of the later military ceremony is merely suggested in the film. At this point, the memory leads Machorka-Muff to marvel at the militarization of Germany that "these Christians" had been able to achieve and wonders what his old general would have to say about it. Here is where the documentary aspect of the film is introduced in the form of newspaper clippings. Straub describes the method as the opposite of the Bach film: "In Machorka-Muff I made use of reality, so that the fiction, let's say the satire, should become more realistic." But he stresses that most of the film is fiction, whereas the newspaper sequences make up only one and one-half minutes of the seventeen-and-one-half-minute film.[41]

While he kills time in the city, Machorka-Muff idly looks through the newspapers. The newspaper clippings are shown full screen, at first alternating at angles, then horizontally, so there is no longer a suggestion that these particular articles are in the paper Machorka-Muff is reading. Instead, they form yet another surrealistic intrusion into the film, much like the dream sequence, and are also accompanied by organ music (a dissonant improvisation by

François Louis). The newspaper articles document the preparation for German rearmament on a number of fronts:

Religious/philosophical: "Is a Christian permitted to kill?" [Christ did not insist that soldiers give up their profession.] "The most perfect Christian will be the most useful soldier."

Economic: "Armament industry in free competition."

Political: "Defense is the citizen's duty."

Adenauer: "Neutralization would be acquiescence."

Strangely enough, Färber criticized the film for not being radical enough in 1964, since the devices "still available" to the cinema, particularly the strategy of ellipsis and the exclusion of a more penetrating intellectual content, reveal its impotence.[42] The critique brought a quick response from Straub, which is typical of his comments on the films over the years. In a letter to Filmkritik , he defends the militancy of his work against those who misinterpret it: "I have forged out of the Böll satire a naked weapon for those who are neither 'militaristic' nor 'antimilitaristic' (antimilitarism is, like laughter, a narcotic for the privileged). . . . Even supposed leftist intellectuals react to Machorka-Muff as if they had expected pornography and were shown a marble venus."[43] Straub asserts that the quality of the weapon is not dependent on a "message"—which would fall into the category of pornography—but on the film's aesthetic integrity. It is a weapon, but "for those who have eyes and ears for what my old master Robert Bresson calls 'matière cinématographique.'" This double gesture of political radicality and loyalty to artistic tradition is then repeated with Straub's double dedication of the film "to the author of The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui [i.e., Brecht] and to that of The Rise and Fall of Legs Diamond " (i.e., Budd Boetticher, who directed the film at Warner Brothers in 1960) and his conclusion that it is "built on the equation M = M."[44]

This stance in regard to a leftist response to Straub/Huillet's first film is characteristic of Straub's political and aesthetic polemics. Most often, the explicit gestures placing the works into contemporary political contexts are in the form of a dedication, mentioned either in the film or separately by Straub. Moses and Aaron , for instance, had difficulty being cleared for television broadcast because of a handwritten dedication to Holger Meins in the opening credits (Meins died in a hunger strike in prison as a suspected Red Army Faction terrorist);[45] the Bach film was "dedicated" in conversation to the Viet Cong;[46]Antigone , in Straub's comments immediately following the stage production in May 1991, to the one hundred thousand Iraqi victims of George Bush's New World Order.[47]

In his letter on Machorka-Muff , Straub connects his political radicality to

a respectable aesthetic tradition with the references to Bresson, Brecht, and Lang and to a leftist tradition of political art (regarding capital and violence, with the reference to Brecht's Arturo Ui ). But in all the debates over Straub/Huillet films, Straub has denied that they are incompatible with the "popular cinema." Hence the reference, along with Brecht, to a contemporary product of the Hollywood studio system, The Rise and Fall of Legs Diamond . All of these gestures against the categories of film culture still play a role in Antigone in 1992. Here, as early as 1964, is a sign of resistance to the "art cinema ghetto" that some perceive as the bane of New German Cinema in its confrontation with Hollywood's world domination.[48]

Straub's cinematic utopia envisions high art films such as those by Straub/Huillet coexisting with mainstream forms. This is not an acceptance of the impoverishment of the mainstream cinema, but too often Straub/Huillet's distance from the mainstream obscures their longing for a popular film industry that would include their films. This is another sign of their "respect for the audience," that they do not wish to address an elite. After all, Straub's letter says Machorka-Muff is for "lovers of the Western," and he would have liked the short film to have preceded Westerns in theatrical bookings.[49]

Despite the public anticipation of what fruits the Oberhausen Manifesto of 1962 would bring, the selection committee did not choose Machorka-Muff for the 1963 festival. Although the influence of the old guard had certainly not been dismantled by the manifesto, even "leftists" opposed the film, according to Straub. Even Böll refused to defend Straub/Huillet's film of his work, which Straub ascribed to fear of the unpredictable mass film audience as opposed to the readers of his literary work. The novelist here perhaps merely reflects the separation between film and literature that was greater in West Germany than in France, for example. If filmmakers thought of themselves as Autoren , the inverse was generally not the case.[50] But if Böll thought the film satires of the 1960s too explicit, he did not successfully avoid political controversy. By the 1970s, Böll was accused of being an "intellectual father" of left-wing terrorism and a terrorist "sympathizer." Hence the irony he contributed to Germany in Autumn : by 1977, even Sophocles' Antigone is too controversial for German mass media distribution.[51]

The Bridegroom, the Comedienne, and the Pimp

It is perhaps testimony to the uniqueness of the period of the "student movement" around 1968 that the political significance of Bridegroom was widely appreciated. In this film, the relation to contemporary politics is not nearly as clear as in Machorka-Muff , and the modernist separation of elements reaches a high point. Yet the film received the award of the Mannheim Film Festival in 1968, not because of a jury decision, but because of the popular

demands of the youthful crowd discussing the films after the festival was over.[52]

The revolutionary political impulse of the film remains even more general than the reference to "resistance" in the Bach and Böll films. As in the earlier work, artistic forms are the means chosen to express this liberation, and the connection to Germany, or any other political entity, remains metaphorical. Aside from the language and locations, the only reference to Germany in the film is in the graffiti of the opening shot, behind the titles, with the words, scrawled in English among other barely legible names and dates on a wall of the telegraph department of the Munich Post Office, "Stupid/old Germany/I hate it over here/I hope I can go soon//Patricia/1.3.68."[53]

As in a musical structure, this time more in the sense of heterogeneous variations on a theme rather than a fugue, a motif is established: a female prisoner who desires to escape. The static, fifty-second shot of the graffiti is followed by a tracking shot along the Landsberger Strasse in Munich. The shot is photographed from a vehicle proceeding with varying but almost constant speed, so that the sidewalk and the businesses facing the street are observed from right to left. Anticipating the driving shots in History Lessons , this tracking shot derives its pacing and "action" from the appearance and disappearance of identifiable elements before the neutral, urban-industrial background—the people who work at night on this street, the prostitutes, walking, standing, talking to each other or to men who pull up in their cars. Aside from these women's ephemeral presence, pace and variety are lent to the shot by the dramatic appearances of billboards and industrial signage out of the darkness—signs generally for steel plants and oil companies, accompanied by several gas stations, the only other location of human activity. To the theme of female imprisonment is thus added the motif of economic production and exchange: heavy industry, energy, and women's sexuality, all presented in parallel fashion to the camera as commodities.

At the same time as these motifs are being presented to the viewer without interpretation, the dilemma of cinematic form is also raised. The camera still has not isolated an image or an action, since its tracking from right to left is constant. Almost two minutes at the beginning of the shot are silent, adding to the evocation of the origins of cinema. Here the question of the "birth of the movies" is proposed: When does one cut the film? While posing this question of the birth of the movies, with all the elements present—human labor, industrial infrastructure, market exchange, light, motion, and commodified desire—the shot avoids the issue by fleeing the cinema temporarily to another source of aesthetic structure, the music of Johann Sebastian Bach. The music begins in the middle of the shot and is itself an excerpt from the Ascension Oratorio, also with a text praying for deliverance: "Thou day, when wilt thou be / In which we greet the savior / In which we kiss the savior / Come, make

thyself appear!"[54] Once the music begins, however, it provides to the film a reference to time that gives logic to the cut at the end of the shot, simultaneous with its conclusion. This method of calling attention to the artificial connection between real time and cinematic narrative time is echoed at the conclusion of Fassbinder's The Marriage of Maria Braun (1978) as well. The conclusion of the explicitly timed "seven minutes" of soccer action on the sound track determines the end of the film's narrative with the explosion of Maria's house.

The Bach music supplies a stark contrast to the mundane scene before us. The spirituality of the religious text and the choral singing shockingly elevate the commodity exchange implied by the visual image. The most striking effect, however, is the transformation performed on the visual image by the presence of sound, especially this beautiful and lofty music. First, a dimension of meaning is added, another evocation of the longing for escape; and second, a sense of temporal structure or rhythm is added to the visual track, so that an expectation arises that its eventual cutting will have a meaning. Indeed, the music supplies both to this shot and to the end of the film one very practical requirement: an expectation in the audience that there is a reason to cut the film at the place where it cuts because the musical passage has come to its ending. This, of course, is perceived as the reverse of the actual procedure, since the end of the music is matched to the chosen final image or the end of the film roll. Then the music is laid over the shot from the end to the beginning. The crucial decision is thus not the ending of the visual track, which is the sensation aroused in the viewer, but the beginning of the sound track (a technique similar to that of Introduction to Schoenberg's "Accompaniment to a Cinematographic Scene" ).

The use of the sound track to give structure to the film also relates to Straub/Huillet's use of texts for the same purpose. Since the filmmakers separate to a great extent the narrative structure from the cinematic form of their films, the narrative of the texts—or the simple duration of their delivery—provides one method of determining beginnings and endings of shots. The connection to early cinema is made by calling attention to the difference between the two logics, that of cinema and that of narrative. Bridegroom thus functions as a precursor to Straub/Huillet films that juxtapose text and landscape, such as History Lessons, Fortini/Cani , and Too Early, Too Late . It also recalls the centrality of editing to the filmmaking of Straub/Huillet, and Huillet's role is perhaps the greater here. As Handke put it, "Editing is the essence of film." And after giving directing students hands-on experience with editing Empedocles , Straub/Huillet wondered why the students still wanted to study directing at all.[55]

The motif of Bach's Ascension Oratorio returns at the end of the film as the poetry spoken by Lilith concludes with the words "eternal father of lights." Rather than the conclusion of the choral passage from the film's first shot, we

now hear its beginning, signaling an element of rebellion against the constraints of the world as we see it before us. Again, the end of the musical passage dictates the end of the visual track, and the theme of deliverance is repeated. Lilith, another prostitute, has liberated herself from her pimp at the end of the film and, in a gesture repeated in other Straub/Huillet films, turns toward the light of a window.

After the initial driving shot ends, following the cues of the music, another "movement" begins which does not initially appear to take up any of these themes. Rather than the shock of beginning and remaining in the visual space before a moving camera, the next shot returns the camera to the interior, a static camera, and the world of the theater. If the initial shot corresponded to the early cinematic tradition of Lumière, with its documentary emphasis, the second might logically connect with the other early film tradition, Méliès's studio-bound work (minus the magic). Historically, however, the world we see before us is an anachronistic one: The shot consists of the entire performance of the play Pains of Youth (1926) by Ferdinand Bruckner, as adapted and directed by Straub at Munich's Action-Theater in July 1967.[56] Straub had initially wanted to direct Brecht's The Measures Taken , but the Brecht family would not grant the rights. Instead, the group offered Straub the Bruckner piece, which he initially resisted until he had reduced it to a mere eleven minutes. It was performed on the same program as Fassbinder's first play with the Action-Theater, Katzelmacher . The antinaturalism of the performance is obvious, which at least in an abstract sense could connect to the cinema of Méliès. But even more pertinent is the source of the play—the expressionist theater contemporary with the "Golden Age" of German cinema in the 1920s. This—again without the magic—is the cinema of Dr. Caligari .

It would seem that the reduction of a full-length, three-act play to eleven minutes would destroy the original aesthetic impact, but, given the expressionism of the original work, this is not entirely the case. In the filmed performance, the actors walk through their roles, taking positions in relation to each other as they recite machine gun-like the lines that reveal the action taking place. Straub has indicated that it may be impossible to understand all of the content of what is taking place but that this is not a disadvantage, since what one does perceive is a series of constellations. This is not at all inconsistent with expressionism or the Chamber Theater that developed parallel to it in 1920s theater and film: The characters are significant not as naturalistic representations of individuals but as types in dramatic situations or hierarchies. Even in Straub's reduced version of Bruckner, these constellations are clear: the aristocrat, the devil-may-care medical student, the arrogant pimp, the innocent maid from the country. The cynicism of the postwar 1920s and the 1960s in regard to bourgeois culture and power structures is evident in both versions. The threat of the pimp to force any woman he chooses into prostitution

(or marriage), the ridicule of German classical culture (Goethe) as a mere trapping for empty vanity, and the close connection between sex and death (murder or suicide) are striking similarities between both the early 1920s and the late 1960s: "You long for it as for the knife," as the character Freder (played by Fassbinder) says. Only a cryptic fragment of a Mao quotation provides a link to politics of the 1960s in this shot. Most of the slogan is obstructed by backdrop, but as with the drastically cut play, the sense is clear: "Only when the arch-reactionaries are — will it be possible to —." Similarly, Straub called the film "the last judgment of Mao and of the Third World on our world."[57]

Again by way of contrast, this shot develops the theme of temporality initiated by the traveling shot, but in an entirely different direction. In the shot on the street, a sense of rhythm only arises from the random comings and goings of the women and cars, in interaction with the constant motion of the camera itself. Once the music begins, a rhythm is added to the shot from outside that gives it an aesthetic structure without altering its content. In the stage shot, the rhythm arises only from the delivery of the lines and the motion of the actors. At first viewing, most people have assumed that the performance of the film is entirely expressionless, but this is far from the case. Since the delivery of the lines lacks expression, this actually serves to exaggerate two aspects: meaning and time.

Because so few cues are given as to the identity of these people and their projects, we are all the more intent on figuring them out and are all the more shocked by their lack of affect in the face of conflict, violence, and death. Rather than attend to their histrionic demonstration of these experiences, we are able to ignore the necessary walking about in order to strike the poses that reveal the constellations where they take place. Since the attention to the acting is reduced and the concentration on the language is increased, the temporal element is also exaggerated, this time by the speed of the actors' line delivery, the placement and length of their pauses, and the pauses introduced by physical movement from one constellation to another. Far from being monotonous, this rhythmic arrangement of sound and silence is quite musical and dramatic.

Their collaboration in the political theater of this period was also the source of Straub/Huillet's influence on Fassbinder. Most critics limit their influence to the latter's early films, such as Katzelmacher (1969), which in the stage version was performed together with Pains of Youth . In the Fassbinder film, the actors are also arranged in almost two-dimensional constellations against rather static backgrounds, which are then broken by abrupt entrances and exits from the sides. Contrasted with these scenes are tracking shots of alternating pairs of characters who walk toward the camera as it moves backward through a narrow apartment courtyard.

Fassbinder had also dedicated his film Love Is Colder than Death (1969) to Claude Chabrol, Jean-Marie Straub, and Eric Rohmer,[58] and the arrangement of characters to show "attitudes," as was done in the Bruckner play, persists throughout Fassbinder's work. Wilfried Wiegand connects Effi Briest (1972-1974), for instance, back to the "Dreyer-Bresson-Straub tradition."[59] Also, Fassbinder's avoidance of exterior or landscape shots, except to show how inaccessible they are, seems to connect to Stockhausen's description of the camera as "sheet lightning" in Machorka-Muff .

That Fassbinder "learned to direct" from Straub and the evidence for this in Fassbinder's early work confirms the "Brechtian" aspect of cinema they share in regard to work with the actors. Fassbinder's irritation with Huillet as the more "rigid" of the two indicates that she and Straub rehearsed the Action-Theater actors together. In a 1974 interview, Fassbinder confirms this aspect of Straub/Huillet's influence.

Q: Has Straub influenced you?

RWF: Straub has been more like an important figure for me.

Q: But weren't you inspired by him to use a slow narrative rhythm, and a principle of real time in which occurrences on the screen last exactly as long as they do in reality?

RWF: What was more significant for me was that Straub directed a play, Krankheit der Jugend (Ferdinand Bruckner) with the Action-Theater, and even though his version was only ten minutes long, we rehearsed it for all of four months, over and over again, for only two hours a day, I admit, it was still really crazy. This experience I had with Straub, who approached his work and the other people with such an air of comic solemnity, fascinated me. He would let us play a scene and then would say to us, "How did they feel at this point?" This was really quite right in this case, because we ourselves had to develop an attitude about what we were doing, so that when we were acting, we developed the technique of looking at ourselves, and the result was that there was a distance between the role and the actor, instead of total identity. The films he's made that I think are very beautiful are the early ones, Machorka-Muff and Not Reconciled , up to and including Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach , though Othon and other films since then have proved to me that what is most important to him is not what interests me in his work.[60]

The third portion of Bridegroom leaves the theater and enters the realms of ritual, love story, and the gangster genre. This section is composed of nine shots, and for the first time, camera motion is coordinated with the movement of a character and with cinematic suspense in the form of a car chase. As with the static shot of the power constellations in the Bruckner play, here we also have only a suggestion of the characters (even less): The woman bids her lover

good-bye, urging him to be careful. The man's motion to the elevator produces the powerful expectation that it will follow him when he reaches the entrance of the building, but instead the next camera placement is from behind the man lurking in wait in a car outside. So the doubling of point of view—our initial identification with the character named James and the second identification with a malevolent pursuer's view of him—creates in a single edit the sense of a gangster film or film noir. The absurdity of the reduction is an added aspect of distance from the drama: A VW Beetle pursues James's BMW. He leaves the car at the end of a reservoir and runs up an embankment (the only energetic movement in the entire film). His pursuer enters the shot from the right, scrambling up an embankment after him, but seems to be daunted enough by James's kicks to slide back down out of the frame as James continues to struggle upward.

With this sequence, crystallizing the drama of a car chase into three shots, we have left the world of Méliès's early cinema to reach perhaps Buster Keaton, for whom the position in the frame and motion into and out of it have existential power. The narrative space of these three shots is abstract but is defined totally by the sense of danger and a chase: James leaves home, descends, enters the street and the public realm (the car), is pursued out of the city into nature (with the sound of falling water). The sequence begins and ends with static shots, but in the intervening shots the camera pans left, right, and left. To escape, he ascends again into an unknown space, but in any case out of frame and in a direction where no camera movement has followed.

The next shot confirms that he has escaped, since it depicts the marriage ceremony between James and Lilith, the woman he had left before being chased. Their vows, conducted in an austerely modern chapel and photographed in a single shot, constitute a different kind of ritualized performance than the theatrical shot. Here there is no dramatic variation of rhythm but only the repetition of the expected ritual, also in the real time it takes to recite them. The only drama engendered by the shot is that of its composition in relation to the camera and a real or implied audience. Here it is quite dissimilar from the Bruckner play, which had been photographed from an angle only slightly to the left of center, and instead related to the performance spaces of the Bach film. The angle of the shot reveals the couple to be married on the right, spaced carefully so that the priest and his attendant are visible on the left. The open space of the composition, however, is toward the front of the church (the left) rather than toward the back where the congregation would be. There is no reason to believe that there would be a crowd, but the ritual does refer to witnesses of the wedding who also commit themselves to support the married couple in the future.

This is reminiscent of the exclusion, but implied presence, of an audience in the Bach film. The composition shifts the weight away from an actual congregation of witnesses, but the text invokes one. Thus the audience is

presented with the possibility of taking the place of the witnesses. But the angle of the shot makes it a conscious tension rather than a "natural" identification with the space of the audience as in the theater segment.

The shot of the wedding is followed by a more dramatic mise-en-scène as we see the car of the wedding couple emerge from the distance and arrive, followed by the panning camera, at a new suburban house. As they disembark, James recites poetry to Lilith, lines from St. John of the Cross, beginning, "The time at last came/For the old order to be revoked, /To rescue the young Bride / Serving under the hard yoke."[61]

Peter Jansen has observed that the film follows an alternating structure of exterior/interior/exterior (although this is not strictly true, since the third section includes both interior and exterior shots).[62] His observation of the use of empty space is of interest, however, although it also assumes a schematic consistency that goes beyond what Straub/Huillet actually construct. Jansen asserts that a space is always shown (regarding interiors) before the people enter them and in the long shots (such as, in Not Reconciled , Schrella crossing the housing blocks that are his childhood home or Johanna's long walk to get the gardener's gun): "The imagination of the viewer has each time already penetrated the scene, is present in it and at home, before the figures of the film join in."[63]

The effect of this seems to be somewhat different from what Jansen implies, however, especially in the shots of approaching cars in Bridegroom . There is the element of almost satirical suspense, since each long shot of an approaching auto could be seen as part of the car chase. It is not entirely true, however, that the spectator is at home in these shots. The suspense created by the car's long approach is perhaps exaggerated by the fact that the spectator's quizzical imagination is already "at home" in the shot, but the approach of the car also disrupts that familiarity. In the first car chase, the loudness of the sound and the fragmentation of the cars as they break the bounds of the frame once they reach close-up are disturbing. The comfortable space set up in the long shot is spilled over by the violent vehicles, and the viewer becomes aware of space outside the frame that had been inviolable for the seconds previous.

The arrival of the car in the final sequence of Bridegroom is another matter. This time the frame is not broken, but instead the camera pans to the left to follow the car and to reveal a house—another narrative space—that had not been visible before. This again builds suspense and disrupts the "at home" feeling that Jansen describes. The result is a dramatic interaction between space, mise-en-scène, and camera movement—which all work on audience perception separately to create an effect.

The shock of the cut reveals Fassbinder, the pimp from the Bruckner segment, already inside and holding a gun. This also goes against the pattern Jansen describes, since the camera retroactively takes on the dual function of narrating and lying in wait, as it had done in shot 2 of the film noir sequence.

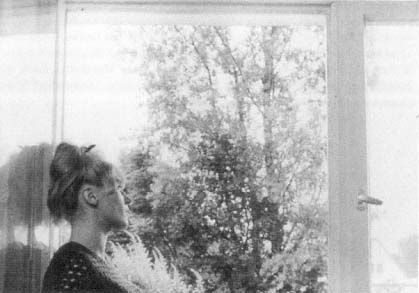

The final shot of The Bridegroom, the Comedienne,

and the Pimp (Lilith Ungerer). Courtesy New Yorker Films.

But here, the narrative structure is carried by forces independent of the threat of the pimp to resubjugate Lilith.

The camera moves quite wildly in this scene, starting with a nearly full shot of Fassbinder threatening, "One doesn't flee our family so simply, Lilith," echoing Inn's claim at the end of Machorka-Muff that no one has successfully opposed her family either. After the pimp has spoken, the camera pans and tilts right to show Lilith and James, then pans straight across to the left, following Lilith in an uninterrupted movement to the window. There she delivers her final speech from St. John of the Cross about the passion of her "heart of clay" that burns with flames that quench thirst and would rise "up to the high peaks / of that eternal Father of Lights." The shock of this second pan, however, is that its smooth, level motion records the "melodramatic" act of Lilith's taking up Fassbinder's gun and shooting him as she walks past him toward the window. Only Lilith and the gun are framed in the briskly moving shot; Fassbinder is not visible even though the pan crosses above the space where he was initially seen. Neither the motion of the camera nor the pattern of the poetic exchange between Lilith and James has been interrupted.

The effect of this camera movement, as one can see in related shots in Not Reconciled and Class Relations , is for the character's liberation to be inscribed across a camera movement that is not dependent on "narration" but that has

a telos of its own. After the camera has come to rest and Lilith recites her last verses, it then slowly tracks in to place her more literally on the edge of the window frame. Outside, the leaves blowing in the wind become even more vivid as the Bach music is repeated to the close. Much like the pans to windows at the end of Not Reconciled and Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach , the evocation of the cinema's essence in light and framing, independent of the character's lot, intimates an avenue of liberation.