3—

Traces of a Life:

Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach

Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach will be treated first, because it was the first project Straub undertook even though it was only realized as the third Straub/Huillet film. It is also the film that brought Straub and Huillet together and brought them their widest international recognition.[1] The story of their struggle to get the film produced spans their entire ten-year residence in West Germany (1959–1969). Straub/Huillet's filmmaking practices, their long-term confrontation with German culture, and their other projects of the time all developed out of the Bach film.

Chronicle is composed of images of documents from Johann Sebastian Bach's life, musical performances in historic locations, and a few fictionalized scenes—all held together by a voice-over narration by his second wife, Anna Magdalena Bach. The film begins with Bach's tenure as Capellmeister at the court of Anhalt-Cöthen, where he and Anna Magdalena met, and ends with her description of his final illness and death. The role of Bach is played by the Dutch harpsichordist Gustav Leonhardt, and Anna Magdalena is played by Christiane Lang-Drewanz.[2] The film marks a transition in Straub/Huillet's work in that it initially had a script that was written by the filmmakers rather than excerpted from other texts as in all subsequent films. But whereas Roy Armes writes that Chronicle is the only Straub/Huillet film without a literary source, this is not accurate.[3] Most of the language of the film is taken from documents; letters, texts of cantatas, the necrology.[4] Although Straub claimed only the title came from Esther Meynell's book, The Little Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach , the narrational gesture and the chronological sequence of music and events parallel its structure.[5] The method of letting musical structures suggest the form of the film rather than being subordinate to it is, however, a consistent aspect

of Straub/Huillet's treatment of all the material they select for their films. Research on the documents concerning Bach's life also brought the filmmakers into contact with Heinrich Böll, whose work forms the basis for their first two finished films. And finally, the struggle to make the film, involving as it did the rallying of colleagues from various countries, reveals the political nature of filmmaking in Europe in the late 1960s. In this period, the formal difficulty of the film was taken as an aspect of its revolutionary value, something that became less and less possible from the 1970s onward. Straub traces his own beginnings as a film director to the Bach project. He at first suggested that Bresson make it but was told he should make it himself, since it was his project. Thus Straub began his path toward directing his own films "as one falls into a trap."[6]

The saga of Straub/Huillet's struggle to get the film produced in Germany is as complex and compelling as a film plot.[7] In an interview with Cahiers du cinéma , Straub listed the reasons the film had been turned down. "One pretext: it's a fiction film. Another pretext: it's a documentary. A third: it can't be an audience success. What is piquant is that this last pretext comes from the North-Rhine Westfalian 'Kultusministerium' [Ministry of Culture] which subsidizes precisely films on music."[8] The idea for the Bach film originated in 1954,[9] and the screenplay was written and researched between 1954 and 1959. The film could have been made as early as 1959, when the producer Hubert Schonger offered financing for it if Straub/Huillet could raise the remaining DM 100,000. But the search for financing delayed the film another eight years, with two films intervening.[10] Straub/Huillet had tried every possible avenue from the smallest distributor to Bavarian Television, UFA, and DEFA, the state-owned studio of East Germany. A representative of the Pallas film company in Frankfurt who had been ready to support the film met with a car accident.[11] Grants were repeatedly denied by the Federal Film Subsidy Board in Bonn and by the Culture Ministry in Düsseldorf.[12] These efforts were not in vain, however, since the contacts made in the long struggle to get funding for the Bach film led to both the material and the financing for the two Böll films as well as to the stage production at the center of Bridegroom .

Straub said that he had met Böll in Paris when he had been looking for someone to consult about the language in the Bach screenplay. Böll's advice had been to leave the antiquated German exactly as it was except for a few minor changes such as the more comprehensible phrase "to appeal" in place of "vozieret."[13] After meeting Böll, Straub/Huillet became interested in making a film based on his work. Because of the availability of funding, two such films preceded the completion of the Bach project: Machorka-Muff (1962), based on Böll's political satire "Bonn Diary"; and Not Reconciled (1964–1965), based on the novel Billiards at Half Past Nine . The

struggle for funding of all three films is treated at greater length in the next chapter.

Between the premiere of Not Reconciled in 1965 and the summer of 1967, Straub/Huillet were able to get partial funding for the Bach film, primarily through the co-producers Franz Seitz in Germany and Gianvittorio Baldi in Italy. The months before the actual shooting began in August 1967 were a battle of nerves. The Kuratorium at first rejected the application for production support, prompting supporters of the project to create the Verein Filmkunstfonds e. V to raise money through "shares" of at first DM 1,000 and later DM 500. The fundraising effort, coordinated through the journal Filmkritik , listed among its supporters Alexander Kluge, Volker Schlöndorff, Enno Patalas, François Truffaut, Enrique Raab, and Artur Brauner.[14] Only in July 1967, a month before shooting, did the Kuratorium approve DM 150,000, about half of what less distinguished films received. By that time, however, Straub had already filmed the Leipzig Town Hall with the DEFA cameraman, since all arrangements had been made. Film stock was purchased, with additional footage ordered in reserve, and contracts were signed with Music House Filmund Fernseh-GmbH, which carried musicians' expenses and Straub's salary while the additional financing was still uncertain. Despite the film's artistic success and its invitation to festivals such as those at Berlin and Cannes, the West German film bureaucracy was unmoved. In the summer of 1968, the Filmbewertungsstelle Wiesbaden refused to assign any tax-reducing quality rating to the film—neither "besonders wertvoll" (excellent) nor simply "wertvoll" (good).

When asked about his strategy for making a film about such a major German cultural icon, Straub has claimed that he had been initially unaware that Bach was viewed as such and had begun his work with a blithe lack of prejudice, with the naïveté of a child.[15] That Bach was indeed a German cultural icon became clear as Straub encountered resistance to the production, sometimes disguised in nonsensical technical reservations, such as the claim that there was no place to put a camera in an organ loft. Finally Straub had come to the conclusion that people "consciously wanted to obstruct the film, to prevent Bach's music from getting into the movie theaters. This music had to stay in the concert halls."[16] This resistance to the film, especially by businesspeople and cultural functionaries, led Straub to more provocative statements. For instance, he noted that Bach was relatively unknown in Germany and connected the Bach project to the political struggles around the Böll films by calling it "yet another film about the unresolved German past."[17] The reference to the anti-Fascist impulses of Not Reconciled is of course not merely a result of the reaction to the film but has always been close to the inspiration for Straub's generation to approach European cultural icons.[18] Confronted with a "bunch of suits" (Filmfritzen ) or "Gesetzeshüter"—

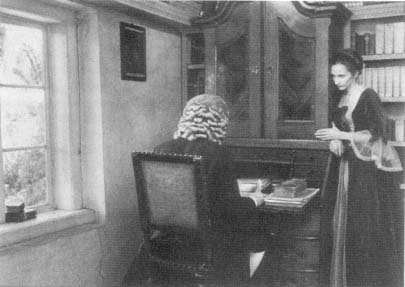

Bach's employers on the Town Council

(Ernst Castelli, Paolo Carlini, Hans-Peter Boye). Courtesy New Yorker Films.

Kafka's guardians of the Law—Straub raised the polemical stakes, saying the film was dedicated to the Viet Cong, with whose struggles against overwhelming opposition he could identify.[19]

Aside from the provocative statements vis-à-vis administrators of culture, Straub/Huillet's work on the Bach film was guided in the main by carefully thought out principles, combined with long years of research and experimentation. Straub had left France for Germany in 1958 rather than be inducted into the army for the Algerian War and had traveled with very little money through both West Germany and the GDR in search of locations and documents for the Bach film. Of this period, Straub reported, "Danièle accompanied me now and then and in between went to Paris to get some money." In the GDR, they visited Eisenach, Arnstadt, Erfurt, Weimar, Dresden, Leipzig, and Mühlhausen and found that most of the actual locations of Bach's work were unusable because of nineteenth-century alterations. "The Thomas school, where Bach lived for thirty years, was torn down around 1900. The Thomaskirche in Leipzig was altered by an organ in a horrible neo-Gothic style."[20] In the old Prussian State Library in East Berlin and in the State Archives in Marburg and Tübingen, Straub/Huillet microfilmed ten times the number of documents that finally

appeared in the film. The search for the authentic locations of Bach's life to shoot the film indicates a practice that Straub/Huillet have never abandoned. The choice of location is never arbitrary and has indeed preceded the screenplays in some instances. The films then explore the physical traces of history that human activity leaves behind and confront these spaces with texts or musical pieces.

Another primary goal, from a musical point of view, was to get away from "romantic performance practice."[21] To this end, Straub/Huillet dedicated much time and travel to finding performers who could use the original baroque instruments, a practice that was not at all common at the time. For instance, they were told that it was out of the question that anyone would ever play a natural trumpet again. But as Straub noted with some pride in 1968, "In the meantime they've managed it, not without some impetus from my film project, which could almost have been realized in 1959."[22] It was also not easy to find a chorus that would take the risk of dedicating only three boys to each part, that is, a choir of twelve. The live recording of uninterrupted performances also goes against industry practice. Straub saw this as an attempt to restore integrity to the musical structures that are so often totally shattered by the power of the cinema to reconstruct them.

We know that nowadays musical recordings are made of a thousand pieces. One simply edits a musical movement, which after all should be a whole, and always was in concert up until the invention and development of sound recording technology; a movement begins and is played to the end. It has a tension from A to Z. . . . Music always consists of following a thought to its conclusion, and that applies to its reproduction as well. So something had to be done to counter the violent habits of current recording techniques, and I hope with this film I have done something in that regard.[23]

The actual application of this approach is contradictory, of course, since Straub/Huillet are making films that are not mere documentations of performances. They do not make arbitrary cuts in the musical pieces they use in their films but rather seek to make cuts that are cinematically motivated and musically defensible.[24] Presenting excerpts of the Bach pieces, with none played in its entirety, stresses the autonomy yet interdependence of the elements of the film, which is part of its theme in other respects.[25]

In her article on Chronicle , Maureen Turim has investigated the arrangement of Straub/Huillet's "cinematic materials" in terms of shot length and composition, rhythm and montage. Distinguishing the film from works of minimalism, despite apparent similarities, Turim describes Straub/Huillet's relation to previous cinematic codes in terms of "écriture blanche," a concept developed by Christian Metz and related to Barthes's idea of "zero-degree writing."

[Écriture blanche ] is the refusal of certain codes (cinematic and narrative) in preference of others which do not yet appear to be fixed codes. It is the refusal to be "recognizable as cinema." Because it simultaneously deconstructs the codes of the classic narrative cinema, disturbing the plenitude of the earlier cinematic text, and presents new codes which startle and thus call attention to themselves, écriture blanche is not only marked by its instrumentality to an intellectual purpose, but is marked by its emphasis on the process of its own construction.[26]

My only quarrel with Turim's assessment is the degree of emphasis placed on intellectual and ideological motivations for deconstructing what she calls the "style of the bourgeois writer-craftsman."[27] We have seen that Straub/Huillet's modernism professes great respect for the work of earlier "craftsmen" in the cinema. Furthermore, although Turim does relate her formal analysis to questions of narrative and cinematic space, there is more to be said in regard to history, memory, and German culture on this basis, as we will also see in later chapters. Finally, the emphasis on the intellect seems to obscure the powerful emotions that can be evoked by Straub/Huillet films, not to mention their emphasis on "play."

Two sequences of shots Turim analyzes can help clarify this distinction. Her description of shots 45, 46, and 47 is productive for an appreciation of the relation of composition to editing in all Straub/Huillet films.[28] The sequence begins with Bach reading a letter he has supposedly just written, then Anna Magdalena Bach in close-up leaning against a wooden panel listening, and finally both of them in a medium shot, which reveals that she is actually much closer to him than the previous shots had suggested, that is, against the same desk at which Bach is sitting. Turim compares the shock of this realization of Anna Magdalena Bach's placement in space to the total lack of spatial orientation for the first image of her in the film, shot 2, an explosively short diagonal close-up with no solid connection to the spaces preceding and following it. The powerful effect Turim describes here is the revelation that there is more continuity in the physical space than the cinematic form had implied.

She contrasts this with the later scene in which Bach forcibly replaces the leader of the boys' choir in the middle of a performance (shots 63–67). This is one of the very few scenes actually acted out in the film. It is also the longest sustained dramatic sequence, since it begins with Bach's entreaty of the governing superintendent of the Thomasschule to take his side in a dispute with the Rector over who is to be in charge of instruction (shot 62) and extends to the two shots of Bach supervising the choirboys at a meal in the refectory, where it becomes clear the boys have had to obey the Rector and Bach has been defeated (shot 67).

In contrast to the scene of Anna Magdalena and Sebastian above, Turim emphasizes that the cinematic codes here imply a greater spatial and temporal

continuity than is visible in the shots. The Rector's return to confront Bach in shot 65 seems to follow his exit in shot 64 immediately. The stairway on which the first confrontation takes place (a favorite location since German expressionism) seems to be contiguous with the doorway to which the Rector returns, and the musical performance seems to have just ended, yet the viewer realizes with a shock that the time of the events must be appreciably later.

The accompaniment of this drama by the Kyrie is indeed a juxtaposition of the sacred with the profane. Because the music is performed with such seriousness and without interruption over the dispute, the sincerity of the religious expression and the artistic passion are not doubted. But at the same time, the film insists on stressing the material basis on which such work rested: As Bach's position is being threatened, we hear the only composition in the film by another composer, Leone Leoni. Turim also sees this scene as central to Straub/Huillet's reinvention of cinematic conventions, since the replacement of the choir leader is for her "the most potentially conventional segment of the film." "Instead," she goes on, "the perturbation of time and space through the destruction of the montage codes of continuity (working against them both by implying a greater discontinuity than exists within the narrative and then a greater continuity than exists) maintains the écriture blanche code destruction of the film."[29]

One can carry this analysis further, however, to examine the context of the sequences where the codes are contradicted in this way. In the first instance, the shocking revelation that Anna and Sebastian have been much closer in space than the cinematic devices had shown produces a shock of intimacy that is all the greater because it stresses the distance between the physical presence of the actors, the characters they represent, and the text being read. This distance is emphasized by the placement of the movement in the two-shot (shot 48), where Anna Magdalena crosses from the right of the desk, behind Sebastian, and to the window at the left—a compositional element with profound significance at the end of this and other Straub/Huillet films (Not Reconciled, Bridegroom, Class Relations ). The discontinuity persists, as Turim observes, because her motion does not begin before the cut. However, the motion is anticipated by the fact that she looks up halfway through the shot, toward the window we see in the next shot. But greater continuity of motion from shot to shot would not only mitigate the shock of intimacy, the motion itself would lose some of its meaning, since it would partly be subordinated to the cinematic narration. This intimacy is underscored by the way in which Anna Magdalena lightly strokes her hand across her husband's back as she walks past him. She continues to look out the window, as we only now realize this was the object of her gaze, and walks in a graceful arc around Sebastian and turns toward him again as she sits on the window seat. The indication of a physical bond is thus couched within her simple motion across the frame, as her gaze has moved from inward

Johann Sebastian Bach (Gustav Leonhardt) and

Anna Magdalena Bach (Christiane Lang-Drewanz).

Courtesy New Yorker Films.

to outward to inward again, from toward the camera's line of view to perpendicular to it to away from it. Since they do not touch in any other shot of the film, this juxtaposition of physical closeness and visual discontinuity is a striking gesture in the film.

The significance gained by gesture and other movement within shots is thus a result of their separateness and autonomy. This, in the realm of mise-en-scène, corresponds to the "counterpoint" Turim describes between shots.[30] "Counterpoint" and "variation" are apt terms to describe the broad repertoire of autonomous cinematic effects the film employs. Camera movement, for instance, which critics have sometimes insisted is not even there, creates a striking pattern. All but two of the pans and tilts are over two-dimensional graphic images: the letters, music, and pictures by Bach's contemporaries of the towns mentioned. The two pans thus become significant in themselves: the first pans from Gustav Leonhardt's hands on a double keyboard up to his face as he reads the music; the second pans along the ceiling from one side of the Apollosaal in the Berlin Opera to the other. One could argue that the pans and tilts on the "documents" correspond to the viewer's act of reading, which at some times corresponds to the "reading" by the narrator or by the musical performers. The rarity of a pan across a three-dimensional space challenges the

transparency of the device and suggests that it is also to be "read" as if it were a two-dimensional document.

Counterbalancing the pans, tilts, and rhythmic cuts between what Turim calls the "graphic inserts" in the film are the long diagonal shots of the musical performances, sometimes containing a track in or out at a carefully selected moment. If the pans and tilts call attention to the kind of reading one does in a film, the tracking shots investigate the camera's and the viewer's relation to space. As Turim puts it, some of these shots could be seen as a dissertation on the effect of camera movement itself.[31] This kind of formal variety must not be underestimated. The range of sound includes complex music, the voice (on-screen, offscreen, or voice-over), and silence. The visual spectrum is similarly broad: the two-dimensional flatness of manuscripts and engravings, intricate and rich images of baroque organ lofts, performers' wigs and instruments; punctuating images of trees against a sky with clouds, waves striking against a stony shore, an expressionist sunrise by Rouault, or simply black film.

As we shall see in regard to the formal analysis of History Lessons , there is a narrative context that forms part of the counterpoint as well. Rhythm and temporality are pleasurably explored in cinematic terms, but in the process, issues of memory, emotion, and cultural meaning are raised as well. An example of this intersection between narrative and form exists in a sequence from the film that corresponds to an anecdote in Meynell's Little Chronicle . Meynell recounts the story of a cask of wine received as a gift from Bach's cousin, who lived too far away to visit regularly in person. The incident has a humorous cast, since the frugal Bach was required to pay a good deal in shipping expenses to accept the cask, which turned out to be almost half-empty. Calculating the cost of the wine on this basis, Bach wrote to the cousin asking not to receive any more such gifts. The humor in the narrative arises, however, not from the documentary record but from the narrative gesture of Meynell's fictional Anna Magdalena, whose words these are. The film, however, does away with the humorous gesture and instead breaks the incident down into several components. First, Bach is greeted on the stairway of his home by an enthusiastic six-year-old daughter who gleefully announces that the gift of the cask has arrived. Then Anna Magdalena narrates the situation with the cousin, recounting facts that are found in the letter. At the same time, Bach's letter is itself shown on the screen in three successive shots. It concludes with the verbose and formal postscript enumerating the expenses involved, which is the documentary source of the humor.

The tensions in this short scene are extreme: The narration in voice-over by Anna Magdalena acts almost as the basso continuo throughout the entire film and functions here as a link to the wider narrative context of remembering Bach's life. The scene starts with the greeting by the little girl, a reenactment of domestic joy that is simple and brief enough to be entirely convincing. At

the opposite extreme from this contemporary example of film fiction is the other cheerful aspect of the sequence, the humorous postscript requesting to be spared such expensive gifts. This, however, is not fictionalized in any way but is merely presented to the viewer in visual, documentary terms. Most viewers will certainly not even be able to read it on the first viewing of the film, and the narration does not call attention to it. Yet here is the narrative counterpart to the performance of the musical pieces that have also been pictured in the film. We see the letter as the physical evidence that the events occurred and are given three avenues of access to the facts: the film narrative, which "imagines" the activity in the Bach household; the process of remembering by way of Anna Magdalena's voice; and finally, the viewer's reading of the letter. This act of reading is emphasized by the tilts from top to bottom, and the fictionalization is documented as Anna's narration repeats sentences taken from Bach's own text on-screen. Throughout, the film shows no writing of either music or text, only "performances" based on reading.

This connects the film's narrative to the performance by the musicians, which is also an act of reading and recitation from documents that have been interpreted. The music thus produced has an emotional effect, touching both secular and spiritual issues, and this effect is preserved by way of the tensions Turim has described and the counterpoint or layering of their narrative contexts. Music critics writing about Chronicle , however, have tended to see the emotional content as intrinsic to each piece of music alone.

Two critics writing in 1968 made detailed comments on the effect of cutting and arranging the selections. Both Friedrich Hommel and Joachim Kaiser recognize the uniqueness of the film's respect for the music and its performance. Kaiser concedes that Straub "succeeded, in pursuing his conception, in achieving musical photography of a restraint and appropriateness hardly seen before. The camera is not transmusically motivated and does not distract with pseudo-virtuosity and optical tricks from the musical material."[32] Hommel also finds that the fact that only complete musical movements are presented "attests to the care with which the musical exhibits are treated here."[33] Both object, however, to what they see as the inconsistency of the film's attitude to the music. The opening chorus of the St. Matthew Passion or the cadenza of the Fifth Brandenburg Concerto are allowed to have their effect, as Kaiser puts it, but he finds their juxtaposition with the andante from the Italian Concerto played by Johann Elias Bach "totally superfluous."[34] Despite the respect the film shows to the structure of the pieces, Kaiser criticizes the filmmakers for using some passages as "background music," and even more so for shifting abruptly in attitude from the quotidian to the sacred.[35]

Both Kaiser and Hommel also criticize the abrupt editing between contrasting pieces. Hommel sees this as an intentional denial of a "breathing space" for the audience: "Emotions, such as those that are relased through

the applause of a concert audience, are undesirable. The screen is to remain pure."[36] Kaiser objects to the fact that the music, which on the one hand is given so much weight in the film, is forced into "a goosestep order (as if all pieces were as similar as geese) on the other." The result, as Kaiser sees it, is the evocation of a vague and undifferentiated sensation of baroque piety and joie de vivre as the culture industry would present it.[37] Although he also would not go so far as to insist on the romantic large-orchestra presentation of Bach's work, Hommel sees the film as being unnecessarily limited by small-scale ensembles and the "stiff and one-dimensional performance style" of Leonhardt as Bach.[38] The effect of the film seems to be, then, that the music is presented in a convincingly authentic style but is irritatingly contextualized rather than being allowed to stand on its own.

The emotional frustration noted by both critics deserves investigation, since it cannot be possible that emotions are simply forbidden. Instead, there is a definite evocation of emotion in the narrative and in the characters of Johann Sebastian and Anna Magdalena Bach. Neither writer has taken the narration of Anna Magdalena Bach very seriously, despite the attention called to it by the film's title. For instance, the mistakes in the singing of the "Trauer-Musik" aria are lamented, without considering that the woman playing Anna Magdalena, not a professional soprano, is singing on camera. The relation of the musical texts to the narrative is also largely ignored, and the English subtitles do not include them at all. For instance, following an image of Anna Magdalena severely ill in bed and the commentary relating how Bach was summoned home, the film reel ends with a peaceful image of clouds between the tips of two trees. The sound is from the cantata "Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme" (BWV 140), with the text

Soul: When com'st thou, my Savior?

Jesus: I'm coming, thy share.

Soul: I'm waiting with my burning oil.[39]

Hommel connects the domestic narrative to his criticism of the small-scale ensembles. "Where Bach's life's work is narrowed down to the perspective of the silently suffering Anna Magdalena, it is ultimately unavoidable that the film takes on the pattern of a family album, in which homey and small-format music-making is recorded as the foundation of all music for posterity."[40] Kaiser is even more sarcastic about Anna Magdalena's "housewifely tone" and believes the music's domination of the film keeps its narrative from being convincing. "If the numerous musical insertions are only to prove that music dominated in Bach's life, the proof is derived from arbitrary material such as could be appropriated from any artist's biography."[41] Hommel sees a contradiction in the filmmakers' attempt to avoid "illustrating any image of Bach constructed by historians." Instead the film

withdraws to an arrangement, where the facts are to speak for themselves. But [Straub] seems to overlook one thing: without interpretation, facts indeed only speak for themselves, or for anyone: Bach's wig would fit a Handel just as well, and no one prevents us in this carefully reconstructed milieu from replacing one Leipzig cantor with another one. Similarly, in even such a faithfully reconstructed interior with house musicians fiddling on old instruments, nothing would stand against playing Telemann music rather than Bach music on the sound track.[42]

What Hommel has missed here is the tension between meaning and lack of meaning that Turim is able to describe using semiotic terms.

We are left with a lack of an easily determined signified, which in effect throws us back to the materiality of the signifier. Signification is achieved not directly (signifier X representing signifieds Y, Z, etc.) but on a bias, through addition, comparison, contemplation of the signifiers, their unintelligibility, their refusal to make sense. We need more than one engraving of a town to build the concept of engravings being a form of representation minimally legible to our modern perception, more than one close-up of music to develop the concept of music as a written code, highly formalized, but legible only to musicians. . . . Thus in this segment the montage of these elements emphasizes that this film is as much about the attempt to recover the past through its records as it is about the life of one man, Bach. It is about antique maps of cities which have since changed, about a script style which is nearly illegible to modern eyes. It is also about the role codes play in communication, about the relationship of musical notation to sounds heard as music. The narrative does not explain these illusive signifiers. . . . The disjunction instead frustrates our attention, the narration with its own terrorization of the text, its lack of immediate comprehensibility is part of its challenge and meaning.[43]

The lack of an obvious relation between the records of Bach's life and his canonization in German culture is thus quite intentional. There is no attempt to make Leonhardt look or sound the way Bach might have, as the film studiously avoids "reenactments" of character or historical events. The images of the documents, the reconstructed (or rather, the rediscovered) spaces where Bach worked, and even the music itself do not bear any incontestable relation to Bach's life as an individual. Instead, to use Grafe's words, documents "function as evidence, as proof; they are not absorbed by the story. In another story they could testify to something else."[44] The central question posed by the film—and I assert that it is the question that lends aesthetic power to it, rather than a proposed answer—is how the music of Bach (as a cultural treasure, religious expression, or simply pleasing music) can at all be connected to the physical life of a historical individual. This is not just a question for interpretation of historical artifacts but rather has a connection to all the dramas of contemporary life: how can anyone, artist or not, know what will be remem-

bered as essential to one's character or as valuable to the lives of others (contemporaries or posterity)? To borrow a phrase from Christa Wolf, one concern of the film is "Was bleibt"—what remains. And what remains of Anna Magdalena's life consists mainly of a few lines written in a Bible and the music she copied for her husband.

Here, the juxtaposition of musical performances with the invented narrative of Anna Magdalena, the domestic concerns as well as the professional struggles, alternatively puts the emphasis on both. Some of the irony of this narration may be lost to some viewers, since the German texts that are sung are not subtitled, such as the cantata text, "How merrily will I laugh" when the world is falling apart.[45] Reference to Bach's identity as an employee also recalls the device Godard uses to expose the material basis for filmmaking, the series of checks signed in close-up at the beginning of the film Tout va bien . But in the case of the Straub/Huillet film, it is the lives of Bach and his loved ones that are expended. The emotional cost of this expenditure is not acted out in the film, nor is the emotion evoked by the acting. The words alone are to convey the professional conflicts and the personal memories, while it is left up to the music and the editing to evoke emotions. The film does not explain what it was about Bach's life that made it possible for him to become a cultural monument. Instead we are confronted with the possibility that, for Bach, perhaps the small pieces composed for Anna Magdalena were just as important as the works for his churches or patrons. In the film, the large public works were no more important to her.

Straub thus would not have been exaggerating when he described the film as a love story. The displacement and concentration of emotions in many aspects of the work are consistent with this description. In this respect, Hommel's complaint that the work resembles a "family album" may not be that far from the filmmakers' intention. Straub did speak of a scene in one draft of the screenplay where he imagined the Bach family on a picnic, a scene that is included in Meynell's Little Chronicle .[46]

In addition to the narrative stress placed on domestic situations, the absence of an audience for the performances in the film functions to intensify the viewers' emotional concentration. Hommel is correct that the usual channeling of the listeners' emotions through applause is impossible due to the relentless pace of the film editing. In addition to the absence of listeners in the film with whom viewers could identify, spatial relations also emphasize the work of performing and inhibit identification with an imagined concert audience. The camera is most often positioned at an oblique angle to the space toward which the musicians seem to be directing their performance. Camera motion underscores this effect, beginning with the Brandenburg Concerto that opens the film: After Leonhardt's solo cadenza, the camera tracks back to reveal the ensemble that finishes the piece with him. The precision of this motion was only possible with the big

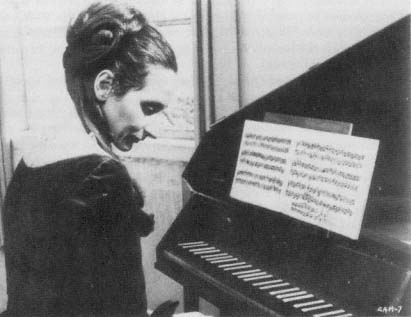

Christiane Lang-Drewanz as Anna Magdalena Bach.

Courtesy New Yorker Films.

Mitchell camera on tracks, a sharp contrast to the much looser use of zooms by other filmmakers since the 1960s.[47] An even more striking example is the cantata (BWV 42) in shot 48. At first, with voice-over by Anna Magdalena and then Bach, the camera frames Leonhardt conducting the "Sinfonia" from the organ. Then it tracks back to reveal the musicians and the tenor, who is seen waiting patiently for his entrance. To begin singing, however, the tenor turns shockingly toward a space that was not "real" to the scene up to that point.[48]

The result is a sensation of distance, which also is explicitly intended by the filmmakers. As in all of their work, the "separation of elements" is a fundamental principle in Chronicle . Straub speaks of the three kinds of "reality" that are accessible where Bach is concerned: "the music, the manuscripts or original texts, and the letters, along with the necrology." To make of this something more than a documentary film, Straub goes on, one has to introduce human beings—that is, the musicians—into the equation. The reality of the traces of Bach's having lived is therefore in tension with the image of Gustav Leonhardt playing the role of Bach.

We won't necessarily say to the spectator, "that is Bach." I would say, the film will instead be a film about this Mr. Leonhardt. Even in the "points" from Bach's life one will respect the performer of Bach as Mr. Leonhardt. The film, the play

consists in bringing him together with these three realities: "writings," "texts" and "music." Only when the ignition between these four elements functions will something come out of it.[49]

In describing what interests him in the work of a performer producing this spark, Straub speaks of layers. He praises the work of Leonhardt because he did not erase all traces of his previous approaches to each scene in developing new ones. Straub's criticism of professional actors is that when they alter their approach, they completely forget what was there before. Nonprofessionals, apparently because their "natural" actions are more essential to the performance, do not erase these impulses but only suppress them.[50]

The supposed asceticism and rigor of Straub/Huillet's method thus seeks to increase the film's impact, not frustrate the audience. The use of original instruments is not chosen out of a desire for aesthetic "purity," for example, but, as Straub has said, because "the music of Bach can reach people of today with the greatest force when it is performed with the means that Bach had at his disposal, because these means are actually new to modern people."[51] The "newness" of the instruments and the distance provided by the costumes are complemented by the concentration on the act of performance itself. Despite the recurring complaints of critics about the "uncinematic" lack of motion in the film—including the absurdly revealing phrase "unless one can call making music motion"[52] —the action of performance and the risk of accident present in any sustained shot of a demanding performance are precisely what Straub finds as exciting as the early motion pictures.

[The quality of chance] exists in every fraction of a second of the film, if only because every musician could make a mistake in every fraction of a second, and there are many of them before the camera. The duration multiplies the quality of chance even more. It's a joke when some say it's a static shot, the camera doesn't move, nothing happens. There is more happening than in a pan, a car chase, or a pursuit. Every finger is moving, and one even senses the air, and besides, that is the essence of the cinematographer: They say when people saw Le déjeuner de bébé or L'arroseur arrosé by Lumière, they didn't cry out: Oh! bébé is moving, or l'arroseur is moving. They said, the leaves are moving in the trees. The bébé who moved they had already seem in the magic lantern. What was new for them was precisely that the leaves were moving. The "leaves" in the Bach film are the fingers and hands of the musicians and the unbelievable gestures of Leonhardt, which are not at all monotonous.[53]

One part of the equation in the Bach film is the "documentary quality" of the performances—the spark that is to be ignited between the types of reality. Straub has gone so far as to maintain that the reduction of the nondocumentary aspects actually increases the "novelistic" quality. He contrasted the Bach film with Machorka-Muff , in which the inclusion of "reality" was meant to

make the film more "realistic." Here, he maintains, with even more "real" elements, "in spite of everything the whole becomes almost only a novel."[54] Huillet, too, speaks of this layering of separate elements as an important aspect of their films. Her term is "archaeology." "Fiction is important for us, because, when it is mixed with documentary images or a documentary situation, a contradiction is created, and a spark can flash up. Fiction is very important, in spite of everything, to somehow ignite a fire. (Straub: I think what interests us is to show layers . . .) Huillet: not to eradicate traces, but to build on them."[55]

The "fiction" of the Bach film is carefully defined as that aspect of the film that arises almost in a shock effect by the confrontation between documentary and fiction. The music and the manuscripts presented to the camera and the documentation of the present performance confront the fiction of Anna Magdalena Bach's remembering these images as her husband. The historical memory evoked in the audience by a film about a major cultural figure is juxtaposed in the fiction with the private memory of his wife. This memory, in turn, resonates with the tension and use of memory involved in any performance. The musicians and actors are also acting out a memory, both in performing a past composition in the present and in reciting a memorized text. Suspense is generated because something could go wrong, be lost or forgotten. The fictional confrontation with documentary reality traces the border between present and past, between life and living memory and death.

A number of critics have noted this presence of death as a major theme of the film, and this was also an aspect of the Meynell book from which it takes its title. Meynell's Anna Magdalena says, for instance, "All Sebastian's noblest music was evoked by the thought of death—that used to frighten me a little, now I understand better what was in his heart."[56] In the film, the texts of both the music and the narration of Anna Magdalena make the theme of death quite explicit. Klaus Eder notes that the shot of informal playing of excerpts from Anna Magdalena Bach's "Notenbüchlein" with a small child playing at her feet "is surprising first in its beauty, but also proves an intensive relationship to music in the Bach family; one senses that music belongs to everyday activity." But the large number of children Bach fathered was often reduced by the intervention of death, and this fact is also juxtaposed with the music. As Eder goes on,

The actor of Anna Magdalena reports this in sober, completely unemotional words as if it didn't touch her at all (which is true: an actress is speaking the text); Danièle Huillet's editing follows this information with a cantata ("Christ lag in Todesbanden") that wrests peace and beauty out of inescapable death. Straub shows that Bach's music is an answer to his own life, to the good or mostly difficult situations in it; it is the continuation of life by other means.[57]

Jörg Peter Feurich stresses, however, that the music does not directly illustrate the narrative.

Thus the musical incidents are not only not integrated into the biographical moment—one perceives a leap of phenomena just where they seem to stand in causal continuity or proximity. For instance, when the report of the deaths of two children accompanies the image of Anna at the keyboard with her child playing at her feet, or when the suicide of the Co-Rector seems to correspond to a Memorial cantata.[58]

Hommel sees in this evocation of death yet another trivial effect.

In Bach's music [Straub] senses everywhere the nearness of death of a cultural late phenomenon, even perhaps something like the Golgotha of occidental music. And only for this reason does Chronicle seem to be photographed so without optical ambition: because he sees incarnations of Bach's music arising everywhere, almost mystically, wherever historical facticity enters the picture. Perhaps it has escaped him as he mulled over his mystical theme, that with this drift toward death that he uncovers everywhere in the life and music of Bach, he is only varying the popular sentimental theme.[59]

These two comments reveal how the film presents Bach's music both as an accompaniment to his own mortality and that of those close to him and as a commentary on his historical period.

The force of the film, however, has to lie in the present. If we are to take Straub's comment seriously, that this is a love story, what does it tell us about the possibilities and limitations of such love and its representation in film? As Eder observed, part of the so-called Brechtian method applied by Straub/Huillet (which may have more to do with Renoir) is the practice of keeping emotion out of the performance, so that the structures and meanings themselves can allow an emotional reaction to develop in the viewer. This emotional reaction, I argue, is the result of the unbridgeable juxtaposition of present and past tense in the film, which is also an evocation of mortality and the struggle against it—through both art and memory.

Feurich has noted, for instance, that a major fictional premise of the film is established in the simple statement of Anna Magdalena at the beginning of the film, "He was . . ." From this point on, we are made aware that Bach is dead, that she has survived him, and that these are the memories that she has constructed to remind herself of him. But the viewer's relation to this depiction of the past becomes ambivalent through this doubling of the distance. In Feurich's words,

The past tense, which at first registers her distance from the years in Cöthen, soon becomes ambivalent. It also describes the distance from the dead person whom she has outlived and from herself while he was alive: a distance that approaches

our own, but by such a small degree that we only clearly become aware of the distance from both. When Anna speaks in the past tense, then she ultimately speaks for us too, in constant ambivalence, because she is only present in a "monotone" voice, quoting, reporting. "Capellmeister, Director . . ." are now only facts that do not pretend to contain anymore the past life from which they are left over.[60]

That these are memories and not depictions is underscored by the presence of documents but also by the fact that scenes are enacted in a documentary style, as if they were indeed images in a family album. Schütte notes that the filtering of the image of Bach through Anna Magdalena's memory is consistent with the fact that there is no attempt to represent aging in the presentation of Gustav Leonhardt. This is part of the attempt to preserve the "foreignness" of the past as represented in the film; therefore, as Schütte notes, Bach is not shown composing "but playing music, 'in practice'; no dialogic tension; if there are dialogues, they are treated as blocks placed next to each other."[61] All this gives the film a structure that is not subordinated to a "unified, unbroken line and motion" but rather is a "chain of different types of punctual intensities of the material."[62] Similarly, Feurich notes that "the levels of music, scene, insert, dialogue, and voice-over chronicle stand independently next to and after each other; they not only do not displace or limit each other, but also the manifest contrasts are only appearances: it is a world of simultaneous realities."[63]

Along with the isolation of scenes as locations of memory, there is the arrangement of text into blocks. This, according to Straub, was an evolutionary process of excluding the exchanges between Bach and Anna Magdelena that would have given the illusion of their living in the present. Instead, all the words of the film refer to him in the past, from the standpoint of those—both Anna Magdalena and the audience/filmmakers—who survive him.

Tension between present and past exists in any block of text, as it does in the performance of music. The distance between the words, their meaning, their origins, their recitation, and the audience is an absolute reality. Most cinematic practice, however, attempts to hide this reality, whereas Straub/Huillet call attention to it. The variation between professional actors and lay performers will be discussed elsewhere, but regarding these texts, Straub has stressed both the attraction of accents and the difficulty some actors have in pronouncing German. For instance, in the French version of the Bach film, the on-camera texts are subtitled, but the voice-over narration is spoken in French by the same actress as in the original. Straub said, "I was glad that I could do that. . . . I love accents in film very much. The language is more alive, when it is spoken by someone who has difficulty with it. Then there are hindrances, which produce a greater veracity. . . . This is not new, since the films of Renoir that encountered the most resistance were also those in which characters spoke with an accent."[64]

The film unites two types of resistance: the resistance of the documents against their appropriation (partly conveyed by the difficulty of performance) and the resistance against death represented by both the life and work of Bach and the act of memory in the fiction of Anna Magdalena. Straub speaks of the difficulty of "holding the two ends of the chain together: that it is to be my tale about Bach and still not for a moment improbable as the tale of Anna Magdalena Bach."[65] Huillet had noted already in typing the screenplay that "this was a film about death," and this awareness—building on such fictional sentences as "A few weeks before Sebastian's death . . ."—gave Straub and Huillet a sense of vertigo that at times awakened the urge to end the project altogether. The final crisis was presented in the editing of the last reel.

Then we cut the last reel, where the vertigo started again, as if it were a film in itself. Then it fit together and we noticed that we had won a victory. . . . That is also one of the novelistic aspects of the film, that it tells of a life that burns like a candle. I think a novel recounts a life; the novels of the nineteenth century, the novels of Dostoyevsky and Balzac recounted a destiny. And here one has, perhaps for the first time, a destiny on the screen. . . . The last reel of the film is the proof, that death is the most unnatural thing—I mean that literally—in the world. The last reel gets faster and faster: it is a race, a wager against time. And suddenly it is completed, burned up.[66]

The material nature of life being expended through work, which produces the "love story" of Chronicle , is touched on by a quotation from Karl Marx that forms the frontispiece of the published screenplay. In the quotation Marx writes of human production as being an avenue both to essential self-expression and to love: ". . . to have been for you the mediator between you and the species, and thus to be known and perceived by you as a completion of your own essence and as a necessary part of your self, and to know myself confirmed in both your thinking and in your love. . . . Our productions would be as many mirrors from which our essence would shine unto itself."[67] Bach's labor may have been alienated by the constrained conditions under which it occurred, but the memory of his productivity is a free, human act of love that resists that alienation. Bach's artistic resistance against death and the constraints of his working conditions complements the resistance of both Anna Magdalena and the authors of the fiction against forgetting. Here, despite his naïve disclaimers, Straub makes quite explicit political claims for the role of the film within a leftist understanding of the role of the artist.

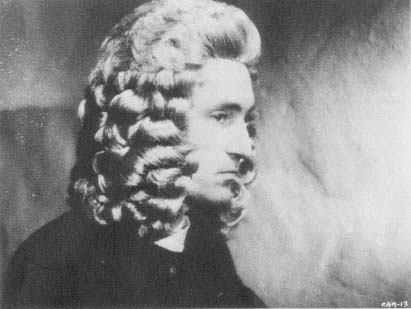

And it is good that someone who "represents" Bach should have had nothing to do with what happened in Germany from 1933 on, either directly or indirectly. [. . .] On the other hand, I discovered in Mr. Leonhardt someone who was much more than an intellectual, who had a great sense of childhood and of provocation. These two traits were very important for Bach. He was and is by far the best

Gustav Leonhardt as Johann Sebastian Bach.

Courtesy New Yorker Films.

interpreter of Bach music. And he took on this musical experiment, a risk, without calculating as most intellectuals do before they will even cross the street: "Oh, what a risk, can I run such a risk?" This is also the reason there are no politics in Germany, because one always pursues the politics of "No experiments."[68]

This film is a bit troublesome. The viewer is in the situation of the Leipzig town councilors, who could not have known that they were dealing with the great Bach. Perhaps it did not interest them. Works of art were not yet sanctified and recognized. But the viewer is also in the position of a twentieth-century person, who knows that this music has been mummified and that it has rightly become a Work of Art.[69]