Chapter Nine—

Renaissance Transformations:

I

The Paideia of Humanism

One of our underlying themes is the continuity between medieval chivalry and Renaissance civic service within both republican communes and seigniorial courts. We shall find a first example in a widely circulating French text by Jean Miélot, derived from a free interpretation in Latin by Giovanni Aurispa (ca. 1376–1459) of an ancient story recorded in the Latin Livy and the Greek Lucian. This text superimposed the chivalrous mold over classical heroes in an underworld debate among Hannibal, Alexander, and Scipio Africanus, who argued before Minos about which of them had most excelled “by his knightly deeds.” It is a striking case of our themes coming together despite their being identifiable with apparently incompatible mentalities. It is also an eloquent example of the way stories and texts can be bent to timely use in different cultural climates. Contrary to Lucian's text, where Alexander and Hannibal won first and second places for military glory, in Aurispa's and Miélot's renderings Minos ruled in favor of Scipio because his achievements were inspired not by a search for personal honor and glory but by the will to maintain the dignity of the Roman name. In other words, at the same time that Miélot presented Scipio as a chivalrous hero, his preface stressed the point, also made by Aurispa, that Scipio acted out of duty to the fatherland.[1] While tracing this intriguing text incorrectly, M. Keen (235) finds “a back-handed dig here at the

quest for vainglory, which had inspired Hannibal and Alexander and had been their ultimate undoing, and which the critics constantly identified as one of the besetting sins of knighthood. The general moral is clear, and its emphasis is on the value of public service, whose aim is to uphold not the fame of an individual, but the honor and fortune of a people.” In sum, we could hardly find a better example of civic humanism at work within the legacy of chivalric ideology.[2]

Aurispa brought Lucian's dialogues and many other Greek manuscripts to Italy from Constantinople. In his free rendering of the competition between the three generals before Minos (1425–1427) he gave the story a completely new twist by introducing into it the humanistic principle that true virtue consists of service to the public good (mostly indicated with the term patria, rendered in Miélot's version as chose publique ). Miélot's version, executed for Philip the Good in 1449–1450, was usually transmitted under the title “Débat entre trois chevalereux princes,” which carried a strong Burgundian flavor. The often accompanying translation of Buonaccorso's text was entitled, in turn, Controversie de noblesse. (The French version of Llull's Ordre de chevalerie also accompanied those two texts in B.R. MS. 10493–10497 of Brussels.)

What deserves all our attention is that the virtues of Aurispa's and Miélot's Scipio are not theological but cardinal (mainly prudence and fortitude), hence secular, and we have noted that this shift already characterized the medieval tradition of curiality on the supporting ground of its Ciceronian component (see my chap. 2). Aurispa identified this ethical strain with humanitas, rendered by Miélot with vertus— chivalric virtues which thus became equivalent to the humanistic ideal of service to the fatherland (la chose publique ).[3]

We could trace our steps even further back and find continuity and implicit alliance between curialitas and humanism, starting with Petrarca and his immediate predecessors. Petrarca's idea of education and Vittorino da Feltre's pedagogical practice were closer to the image of the early medieval teacher of curiality and courtliness than to that of the scholastic dialectician.[4] For, even more than the ascetic monastic circles, the courtly ethic's sternest enemies were the thirteenth- and fourteenthcentury dialecticians who remained the target of most humanists' arrows down to the beginning of the sixteenth century. Those dialecticians had replaced a concern for humaneness and affability with an unswerving quest for pure truth. The Battle of the Seven Arts had

started in mid-twelfth century France on the level of psychological and ethical habits affecting personal careers as much as on that of methods of teaching, learning, and thinking.

I have noted the contrast between the cult of personal greatness, establishing patterns of imitation on the ground of the teacher's charisma, and a desire to prove one's point in purely scientific terms.[5] Stephen of Novara, the Italian master called to Würzburg by Otto the Great, saw his authority challenged when his brilliant pupil, Wolfgang of Regensburg, promised a commentary on Martianus Capella that would outdo his teacher's critical powers. Such a breach of etiquette was to be repeated in other clamorous incidents, as when, in 1028, the Lombard grammarian Benedict of Chiusa appeared in Limoges and without any regard for his hosts' sensitivities proceeded to dispute their belief that their patron St. Martial had been an apostle. Then again, and most sensationally, in mid-twelfth century Abelard criticized the expertise of his teachers, Anselm of Laon and William of Champeaux, after having brashly offended the monks of St. Denis by challenging the true identity of their patron saint. This was not the way the pupils of curialitas were supposed to behave toward their teachers, who were unprepared for the philosophical principle “amicus Plato, sed magis amica veritas.” The avenues to worldly success were, instead, respect, obedience, deference, and diplomatic tactfulness. Abelard, for one, paid dearly for his love of truth above human respect. He never would have risen into a bishopric or a high court. His letter to his son Astrolabe concerning his idea of a correct relationship between teacher and pupil tells much about the new mentality.[6]

No matter how boldly innovative, the early humanistic schools of Vittorino da Feltre at Mantua and Guarino Veronese at Ferrara were still the kind of court schools that trained young knights and sons of princes. They contributed to bringing the ideals of courtly education to fruition. Despite Petrarca's and, among genuine educators of the youth, Vittorino's religious motivations, the new culture was, like that of the medieval knight, generally world-oriented. It sought to refine mind and manners for the secular ends of achieving honor at court and wealth in society, skill in chancery administration, and eloquence in public oratory, including the notarial art. It managed to endow the mind with high humane values even while it fitted its possessors with the credentials for the ruling élite in the city power structure. For such training, ethics was the central and almost exclusive branch of philosophy, and literature the foundation of value and effective communication. Many hu-

manists were at the same time men of action and men of learning, active and occasionally leading citizens of city states, like their proclaimed models from ancient Athens and Rome. True enough, while the chivalric knight had represented the sublimated ideal of medieval clerics and noblemen, the new burgher tried to see himself as a reincarnation of the ancient hero. Yet the goal was similar: to become a civic-minded leader. Pietro Paolo Vergerio's De ingenuis moribus (ca. 1402) addressed this type of humanist as a whole man, scholar and citizen when, citing Aristotle, it warned that “the man who surrenders himself completely to the charm of letters or speculative thought may become self-centered and useless as a citizen or prince.”

Humanistic education ideally aimed at a coupling of eloquence with civic and moral virtues. The actual school practice emphasized the grammatical, rhetorical, and philological aspects of reading the auctores; the extant manuals and commentaries do not generally reflect an equal concern with the formation of moral and social character.[7] In a way, the curial, courtly, and chivalric literature we have been considering embodied such concern more concretely than the statements and exercises of humanistic persuasion. It can be assumed that, as in the best tradition of the medieval royal chapels and cathedral schools, much of the practical impact on students was taking place in the form of the teacher's direct influence by charisma and communication.

At the same time the more worldly side of both medieval and Renaissance educational training, to wit, the rhetorical curriculum (including the ars dictandi ), was directed at what looked like useful preparation for the art of the practicing lawyer. “The critical figures in the origins of humanism,” Lauro Martines reminds us, “were lawyers and notaries, the most literate members of lay society and among its most active in public affairs.” Just as Brunetto Latini had been a notary in Florence, “nearly the whole school of Paduan pre-humanists hailed from the administrative-legal profession,” and the two early leading figures, Lovato Lovati (ca. 1237–1309) and Albertino Mussato (1261–1329), were notaries as well as politicians.[8] The value of rhetoric was stressed not only in special treatises on the art, but also in humanistic political tracts, like the Re repubblica by T. L. Frulovisi (ca. 1400–1480), who held eloquence basic for all members of the city government, including the prince. In his De institutione reipublicae the Sienese Francesco Patrizi da Cherso (1413–1494) reiterated this notion, stressing the government agent's need to persuade others to action. The study of history, especially ancient heroic history, was similarly urged as magistra vitae,

a guide to action as an essential part of humanistic education, as in Leonardo Bruni's De studiis et litteris (ca. 1405). Ancient historians were valued as a repository of eloquence as well as practical wisdom.

Toward the middle of the sixteenth century Peter Ramus produced a large number of school manuals, particularly successful in France, England, and Germany, that contributed to a more practical orientation of educational methods in the sense of pursuing socially attractive positions rather than simply scholarly and intellectual sophistication. But medieval and early humanistic education had been typically concerned with what was regarded as “formation of the mind” rather than with the imparting of directly useful skills: the Trivium Arts were eminently formal rather than professional. This included, to a large extent, rhetorical training, whose relevance to the purpose of forming the lawyer and public man was limited to the development of the “power of persuasion.”

Civic humanism had a counterpart in what one historian has labeled as “courtly humanism” and another one as “subdital humanism,” with reference to the use of the renovated classical ethos to support, praise, and illustrate the new seigniorial rulers.[9] Indeed, humanists could be courtiers, too, and their fashionable panegyrical displays distilled a heady brew of old and new ideals that applied some of the features of the medieval knight and courtier to the new uses of the modern warrior statesman. A most successful funeral oration by the Venetian patrician Leonardo Giustinian for the Venetian leader and general Carlo Zeno (1418, at least sixty-four manuscript copies and six printed editions are extant) praised Zeno as a model captain, even more excellent than the Athenian Themistocles, for having been victorious not by force of arms but through the humanistic virtues of authority, humanity, clemency, affability, civility, and eloquence (auctoritas, humanitas, clementia, affabilitas, comitas, eloquentia ). The Ciceronian matrix, put to a new use, had helped to transform the image of the chivalric leader and refined courtier into that of the modern condottiero in the garb of a humanistic orator.[10] But the widespread enthusiasm for learning that characterized the Renaissance also provided new channels to the aristocrats who had lost the opportunity to achieve power by force of the sword. They became refined courtiers.[11]

If the humanists' public was basically the new oligarchic bourgeoisie in the republican cities and the new aristocracy in the princely signories, it is interesting to see the old topoi of liberality and avarice turned to new purposes and adapted to new social uses.[12] Informed by a taste for

democratic values, Poggio Bracciolini's De avaritia (1428) and De infelicitate principum (1440) both indicted the powerful for their greed and praised them for their patronization of public causes, artists, and humanists.[13] In the dialogue De avaritia Poggio attributed to his character, Antonio Loschi, the bourgeois thesis that avarice could be a source of temperance and happiness in the wise use of fortune. It was a sign of mercantile appreciation for industriousness and thrift—the economic sides of fortitude and prudence.

Humanistic treatises on the nobility and dignity of man invariably emphasized virtue against birth as the true root of nobility, as eloquently argued in Lapo da Castiglionchio il Vecchio's (d. 1390) famous letter to his son Bernardo (1377–1378),[14] Coluccio Salutati's (1331–1406) Tractatus de nobilitate legum et medicinae of 1399/1340, and then, most unequivocally, Buonaccorso da Montemagno il Giovane's (d. 1429) influential tract De nobilitate (1429). This philosophical idea, based on ancient, mostly Stoic speculation, had received the powerful support of Dante's Convivio, which reflected a point of view developed by the new poetic schools for reasons that had to do with the use of courtly love in an alien social setting. When they had to cope with current realities, both Lapo, a jurist of the old landed nobility, and Coluccio, known for his shifting sense of political values, recognized nobility by descent or by holding public office—as did Bartolo da Sassoferrato, translated by Lapo in the first part of his letter.

In Poggio's De nobilitate (1440) the interlocutor Niccolò Niccoli defined nobility as personal virtue, identical to a wise use of assets instead of the simple possession of them, and found only the exercise of virtue a convincing trademark of nobility. His opponent Lorenzo de' Medici objected that a virtue without social purpose is useless and sterile.[15] By vividly examining the behavior of noblemen in different Italian and foreign regions, the dialogue elicited the resentful reaction of some Venetian erudites. Poggio gave more currency to the established distinction that wealth entitles us only to be called “rich,” not “noble.” Replying to Poggio in 1449, Leonardo Chiensi founded nobility in sapientia and virtute.[16] Platina also rejected the equation of nobility and riches (De vera nobilitate, 1471–1478; 1540 ed., p. 43). In book 2 of L. B. Alberti's Dell famiglia we read a hymn to mercatura within a eulogy of wealth as reward not for love or force, but industriousness: noble and great achievements are grounded in strenuous and risky work carried out with liberality and magnificence. Writing in the shadow of a princely court, Guarino Veronese's son Battista Guarino (De ordine do-

cendi et studendi, 1457) declared that only those who could write elegant Latin verse were well educated. This was obviously beyond the reach of the average burgher, busy with other things, but close enough to the training of such refined courtiers as Castiglione, a Latin poet of note.

The best-known texts of this humanistic genre, namely Giannozzo Manetti's (1396–1459) De dignitate et excellentia hominis (1452) and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola's (1463–1494) Oratio de hominis dignitate (1486), were more concerned with the philosophical underpinnings of the humanistic view of man's inner dignity than with the specific social context I am pursuing here. Similarly, Cristoforo Landino's De vera nobilitate (after 1481) repeated what had become standard humanistic motifs, without Manetti's freshness and Pico's philosophical sweep. At the end of the century, in an Epistola de nobilitate, Antonio De Ferrariis, known as Il Galateo (1444–1516), once again submitted an equation of nobility with rationality: “nobiles sunt . . . qui vere philosophantur” (Colucci edition, pp. 140–411). This general theme had been carried on eloquently by P. P. Vergerio, Bartolomeo Fazio, Giannozzo Manetti, Flavio Biondo, Giovanni (Gioviano) Pontano, and the great Pico. The De principe liber (1468) of Pontano (1426–1503), a humanist statesman particularly well versed in court life, was a manual of advice to a young prince. Others of his numerous moral tracts dealt with specific qualities of the public man.[17] His De sermone raised the quality of facetudo, the facetia of medieval memory, to the status of a trademark of the good speaker, namely the one who pleases and avoids offense by clothing his moral judgments in a humorous garb: this distinguishes the man of court from the rustic.[18] In a different vein, Sannazzaro's Arcadia (1480–1496, published 1501, 1504), a successful work fraught with enormous potential for later imitation in many literatures, introduced shepherds and shepherdesses as a counterpart to the Neapolitan court. This model remained the groundwork for generations of pastoral novels, including Honoré d'Urfé's Astrée (1607–1628).

Even on the level of pure poetry, texts that we admire as distillations of the humanistic revival of ancient forms and themes might also, at the same time, respond to solicitations from chivalric customs of medieval origin. Poliziano's poetic masterpiece, the Stanze per la giostra del Magnifico Giuliano, was occasioned by the 1475 tournament in which the burghers' scion Giuliano de' Medici joined in a noble knightly sport to celebrate a diplomatic achievement by his illustrious brother Lorenzo.[19]

Papal Curia and Courtier Clerics

Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini's (1405–1464) De curialium miseriis did not proscribe courtly service for the man of piety, but warned him of the extraordinary difficulties of remaining pure among the soiled: “si potest ignem ingredi et non uri, non illum curiam sequi prohibeo; nam meritum tanto grandius assequetur, quanto periculosius militavit.”[20] This warning found an echo in Castiglione's dialectical notion that true virtue needs testing and stands out clearly only in the midst of vice. Piccolomini had profited from a long, intense experience of court life in Italy and central Europe. As to the term he used in this letter, it is worth noting that the vernacular curiali for “courtiers” was also current in Quattrocento Italy.[21] In tune with the negatively polemical radicalism of the traditional subgenre, however, the pamphlet turned the ambiance of the court into a den of vices that stifled all moral and psychological freedoms, even denying the virtues of eloquence and learning that the idealistic tradition had regularly posited: “in princely courts it is a fault to know letters and dishonorable to be called eloquent,” since “no good art and no love of virtue rule there, but only avarice, lust, cruelty, debauchery, envy, and ambition.”[22]

The field is still wide open for research and, rather than in the Roman social world, I suspect we shall have to search for evidence of the continuity of curialitas in the antipapal documents of conciliary debates. Yet the genre of episcopal biographies, once thriving in medieval Germany, continued its productive life in the Renaissance, including such outstanding papal biographies as that of Nicolas V by Giannozzo Manetti (1459), Julius II and Leo X by Raffaele Maffei, Paul II (1474) by Gaspare da Verona (1400–1474), and those of several popes by Jacopo Zeno (1418–1481) and Platina (Bartolomeo Sacchi, 1421–1487).[23] The great Lorenzo Valla expounded his views on the role and nature of the Curia in his inaugural lecture at the University of Rome, the Oratio in principio sui studii (1455), where he proposed the Curia as the logical center of the renaissance of the Latin language and culture. Even earlier, in 1438 the Florentine humanist Lapo da Castiglionchio il Giovane (1405–1438) had written a short Dialogus super excellentia et dignitate Curiae Romanae where, in a somewhat ambiguous context, the Curia was discussed as a locus for humanistic undertakings.[24]

Given the ecclesiastical connections of the ideological framework we have been pursuing, it is pertinent to recall the relative frequency of

personal association with the Church. With Piccolomini we are in the presence of a future pope. Many important historical characters in Castiglione's Book of the Courtier held (in 1507) or were about to hold important ecclesiastical positions. Bembo was ready to embark on a successful and fruitful ecclesiastical career which saw him secretary to Leo X and then, after 1539, cardinal. Federico Fregoso became bishop of Salerno and almost a cardinal, Bibbiena a cardinal, and Ludovico di Canossa bishop of Tricarico (1511) and then Bayeux. Michael de Silva, Castiglione's Portuguese dedicatee, was then bishop of Viseu and in 1541 a cardinal. Castiglione himself died as bishop of Avila, having been a cleric since 1521 and a candidate for a cardinal's hat since 1527, before publishing his book in 1528.

Dionisotti has estimated that in the first half of the sixteenth century about half of the high literati in Italy moved within the Church as priests, monks, bishops, cardinals, or holders of important ecclesiastical benefices. Even such an apparently unlikely candidate as Ariosto was not only, for a time, secretary to Cardinal Ippolito d'Este, he was himself a cleric and, for a while, hopeful of a bishopric from Leo X.

Rome was teeming with intellectual clerics who gravitated about the cardinals' familiae and the papal Curia,[25] but in secular republics, too, clerical positions were sought for social and political advancement by all sorts of intellectuals. In late Quattrocento Florence, among the leading humanists Angelo Poliziano held minor orders, Marsilio Ficino was a priest, and Pico della Mirandola an apostolic protonotary with minor orders. A prominent humanist who combined high-level philological activity with a full politico-curial career was Niccolò Perotti (1429–1480), archbishop of Siponto and governor of Viterbo, Spoleto, and Perugia.[26]

Against this background, the connection between Castiglione's oeuvre and a contemporary treatise by a leading humanist, Paolo Cortesi's (1465/1471–1510) De cardinalatu, is worth exploring, dealing as it does with the figure of the cardinal as an ideal courtier.[27] Dedicated to Julius II and published posthumously in 1510, it derived from the author's 1504 Sententiarum libri, in turn part of a projected but never accomplished treatise about the prince (De principe ). Castiglione's dialogues are placed in 1507 but were ready in 1516 (first redaction), hence chronologically and ideally close to Cortesi's work as well as to the famous Commentarii urbani of Raffaele Volaterrano, a friend of Cortesi who had grown up in the same circle of the Roman Curia. The main point is that, to put it as does Dionisotti (68), “the cardinal is for

Cortesi more or less what the courtier is for Castiglione: an ideal figure of a man who stands close to the center of a real social sphere, the center, that is, of the ecclesiastical, curial society of the early Cinquecento.” In Italy cardinals were, like Castiglione's courtiers and like chaplains and bishops around German imperial courts, at the point closest to the center of power. Cesare Borgia, for a striking example, had turned himself from a cardinal into a prince.

In the Renaissance, the Roman environment provided little incentive to keep alive the basically Ghibelline tradition of medieval curialitas; moreover, the humanistic climate made it more expedient to lean on the paradoxically less dangerous patterns and motifs of ancient Roman glory. Humanism rings in Cortesi's manner of referring to his cardinal as cardinal/senator, even though he conducted himself more as a cardinal/prince. Furthermore, it was more prudent to deal with style of life and speech than with moral substance and deep-seated merit. Images of once admired courtier bishops could not be safely invoked in an age of rampant absenteeism from pastoral duties. A couple of glaring examples will suffice. Although bishop of two English sees, the active humanist Cardinal Adriano Castellesi never visited England; while bishop of Aquino and Cavaillon, and despite the urgings of his close friend Jacopo Sadoleto, Mario Maffei, another humanist among high prelates, lived in Rome, Florence, and his hometown of Volterra.

Cortesi's encyclopedic work is also somewhat analogous to Castiglione's in the arrangement of subject matter. Book 1, entitled “liber ethicus et contemplativus,” deals with personal character and moral qualifications, education, and cultural aptitudes; the second, the “liber economicus,” deals with the management of the cardinal's princely court; and the third, “liber politicus,” with the cardinal's function as an advisor to the pope, supreme prince of the church, and as a subordinate ruler at his nominal service. The elaborate listing of the virtues required of the cardinal is a conflation of Christian, classical, and courtly prerequisites, including prudentia, memoria, providentia, intelligentia, ratiocinatio, docilitas, experientia, circumspectio, cautio, consilium, and judicium.

In book 2 Cortesi prescribes in detail a magnificent life style for princes of the Church, precisely defining a standard in line with what had been the prerequisites of the high aristocracy and would become the mark of high social status under Louis XIV. The household of the cardinal, Cortesi says, must be ample and imposing, requiring support to the tune of 12,000 aurei or ducats per year on the average. For com-

parison, let us note Cortesi's specification that major officials should earn about fifty gold florins or ducats per year.[28] The College of Cardinals was expected to supply such funds and, should the College run short, the pope was to help. According to the census of 1526/1527 each court or familia of the twenty-one contemporary cardinals averaged 134 servants, administrators, and protégés (the papal familia then numbered seven hundred). Other incomes derived from other benefices, including bishoprics.

This and other tracts on Church government show a distinct similarity to secular political treatises. Del governo della corte d'un signore in Roma by the Florentine humanist Francesco Priscianese (1495–1549) described in detail the management of a Roman princely court of the secular kind with duties and functions corresponding to Cortesi's description of a cardinal's familia.[29] Cortesi himself held a court of sorts in his own house, in what is usually referred to as the Roman Academy (variously conducted by Pomponio Leto, Cortesi himself, Angelo Colocci, and Johannes Goritz, with rather dramatic vicissitudes).[30] Vincenzo Colli, known as il Calmeta (d. 1508), the famous proponent of the lingua cortegiana referred to by Castiglione, was a prominent member of Cortesi's Academy and left a valuable account of it in his biography of the poet Serafino Aquilano.[31] Calmeta makes intriguing comments on the courtly behavior of Cortesi's house circle, ascribing Ciceronian influences to a humanistic discussion centered on decorous public behavior as well as on the principle of decorum in literature and poetry, especially in vernacular works. As to Serafino's career, Calmeta places the court and its patronage system at the centre of that poet's work, despite the lack of appreciation on the part of Cardinal Ascanio Sforza, Serafino's lord.[32] It is an important sign of the realization that courtly environments had become vital for poetic and literary creativity.

Later in the Cinquecento, the literature on the formation, duties, and social status of the bishop gradually started to reflect the shift toward less worldliness and a greater sense of clerical responsibility which was dictated by the Counter-Reformation. Early treatises go from the important De officio viri boni ac probi episcopi (1516) by Gaspare Contarini (1484–1542) to Pier Francesco Zini's (ca. 1520–ca. 1575) Boni pastoris exemplum ac specimen singulare (1555).[33] These Venetian citizens forcefully advocated a type of high ecclesiastic who, consonant with the clergy's way of life in the Venetian republic, purposely eschewed the imitation of princely display of wealth and mundanity that characterized the Roman Curia. Contarini specifically excludes magni-

ficentia as a necessary or desirable attribute of a bishop's life (1571 ed., p. 407).[34] For one thing, the princely courts held by cardinals and bishops, as splendidly illustrated by Cortesi, were made anachronistic, at least on principle, by the Council of Trent's injunction to the high clerics to reside in the places of pastoral assignment. De facto, bishops and high prelates were affected much more by the new sense of austerity than were the cardinals, who continued to live and rule like ostentatious princes holding court. The new priests, foremost among them the Jesuits, were less like courtiers than were their predecessors. Yet the pendulum swung back when, in the course of the Italian wars, the secular courts lost much of their importance and autonomy, while the diplomats who felt superior to the princes started to gravitate toward the only effective court in Italy, the Roman Curia, thus consummating a process of “desecularization” that would have important and lasting consequences for Italian society. As we have seen, this was typically the destiny of several of the Cortegiano' s interlocutors.

Castiglione's Courtier

The reader looks to the Cortegiano (1508–1528) for signs of changing times, new standards, and renewed social attitudes. Burckhardt made us see the Renaissance as a cultural revolution, the civilizing effect of literature and the humanities bringing about social refinement and a new spiritual sophistication. The courtier was the new model for the future honnête homme and gentleman, replacing the feudal hero whose power and authority were more apt to be based on the accidents of birth and social position.[35] The Italian courts became the centers of a new “civilization of good manners” (N. Elias), whether this meant the foundation of a new secular leadership or, rather, as Francesco De Sanctis held, the sterile and artificial separation of a new élite from those popular layers of society that in the Middle Ages had been the source of productivity and cultural vitality.[36]

Castiglione's question, “what is a courtier?” was, after all, similar to the one affecting the ruling classes from the twelfth century on, namely: “what is a nobleman?” The similarity rested in the nobleman's inherent right to be close to the centers of power and to be at court, just as nobility could be granted as a reward for successful service at court. Castiglione did refer to “noble knights” (nobili cavalieri ) as his specific audience.[37] Urbino was the right setting for a marriage of humanism and chivalry: Federigo da Montefeltro (1422–1482), a paragon of hu-

manistic patronage on the largest scale, also sympathized with his northern contemporary the Duke of Burgundy in his appreciation of old chivalry, and had his court painter, the incomparable Piero della Francesca, portray him in full knight's armor at the feet of the Virgin and Child (the portrait, of around 1475, is now in the Brera Gallery). After all, that founder of public museums and public libraries, who had hundreds of scribes copying away precious ancient and medieval manuscripts at his court, endowed his library and museum with money he had amassed from serving as a condottiero, like his illustrious ancestors.

The thread that ties together the three main subjects of our inquiry—courtliness, chivalry, and courtesy—should by now be clear: just as knighthood and courtliness were intimately interrelated in the Middle Ages, so was the Renaissance courtier the direct descendant of the medieval knight. With regard to courtesy, our third ingredient, while discussing Wolfgang Mohr's (1961) description of the twelfth-century courtois lover/courtier as “servant of love,” Minnes Dienstmann, E. Köhler (Mancini ed., p. 276) offered a sociological transcription of it which, mutatis mutandis, could still apply to Castiglione's courtier over three hundred years later:

To be recognized as a powerful lord's Dienstmann already meant much for the knight: having once obtained this goal he must persevere in his service with loyalty, constance, and without hesitation. He must know how to be patient and to endure disillusionment. A great psychic, ethical, and spiritual effort was necessary to advance in the service of the lord. His effort aimed at the ultimate goal of becoming integrated into the rank of lords, but the aspirant took great care not to make his wishes too obvious.

We could say that the Renaissance cortegiano's submissiveness placed him even closer to the curialis than to the knight, and even the “aestheticizing” of manners and conduct that makes cortegiania, in Burckhardtian terms, a work of art, had clear medieval precedents.[38] Furthermore, both curialis and chivalrous knight possessed a high degree of polite refinement (including affability in elegant conversation, musical training, respect for women, humility toward superiors, and dedication to helping the needy and the weak) which distinguished them from the heroic knight of the epic, and which continued to engage the theorist down to the Cortegiano. There may be some irony in the fact that a text which to a De Sanctis or a Burckhardt was a paragon of Renaissance secularism would in fact turn out to be so closely tied to longstanding ecclesiastical perspectives. Classical qualities that Castiglione

derived directly from Cicero and Horace were also reflected in the medieval portrait of the curialis, that is, a combination of decus, honestas, and mediocritas: we find in Castiglione “certa onesta mediocrità” (1.41) and “certa mediocrità difficile e quasi composta di cose contrarie” (3.5).[39] The criterion of decorum would extend to what became known in the seventeenth century as un homme comme il faut, a term still current today. Conforming with the social standards of one's status, no matter how modish and irrational they might be, was a sign of respect for other members of the social group, a sign of deference and vergogna. One would avoid censure and ridicule by adopting set ways of dressing, gesturing, moving, and speaking.[40]

Some strikingly specific instructions remind us of the ethos of the knight errant. Federico Fregoso, in open disregard for contemporary reality, warns the courtier who is engaged in a military action to keep to himself, go to battle in the smallest company possible, and not mingle with the crowd of common soldiers (2.8)—in other words, to behave on the battlefield like a knight of King Arthur or a paladin of Boiardo or Ariosto, rather than in ways that were more likely to save his skin and render him useful.[41] This and other passages point to the concern with personal honor which, we shall see, would soon be defined as the mainspring of chivalric behavior, even above loyalty to prince and country: granted that arms hold first place in the hierarchy of courtly values, Federico Fregoso specifies that the courtier's motivation on the battlefield is principally his own honor: “dee esser solamente l'onore” (2.8).

While dealing with the imposing educational baggage the courtier has to carry, the dialogue enters some differences of opinion on primacy of arms or letters, although all interlocutors agree that the knowledge of letters is relevant. Curiously enough Ludovico di Canossa takes the French to task for “recognizing only nobility of arms with no esteem for anything else, so that they not only do not appreciate letters, but abhor them, holding all lettered men as most base, so that among them it is a great insult to call anyone a cleric. ”[42] Count Ludovico, who against Pietro Bembo was a firm partisan of the primacy of arms over letters (he had trenchantly decided that “questa disputazione . . . io la tengo per diffinita in favore dell'arme” 1.45), nevertheless blames the French for their uncivilized attitude and holds firmly that being lettered befits no one better than a man of arms (“tengo che a niun più si convenga l'essere litterato che ad un om di guerra” 1.46). We have seen how important early chroniclers and clerical advisors considered a liberal education to be for princes as well as for knights at court. It will

suffice to recall Lambert of Ardres on Baldwin II of Guines and Philip of Harvengt's letters to Philip of Flanders and Henry the Liberal (chap. 3 above). It was also important in the romances: just let us think of Gottfried's delineation of Tristan's character and role. The old theme of the primacy of arms or letters spilled over into dozens of treatises of all kinds, and included the clerical argument on whether a cleric could be a better lover than a knight.[43]

Despite these medieval antecedents to the requirement of literacy in the clerics and courtiers, Castiglione's emphatic statement is clearly a reflection of Renaissance humanism: his courtier needs “more than an average degree of erudition . . . at least in these studies that we call humanities,” meaning “familiarity with the poets, the orators, and the historians,” music and the arts, Latin, Greek, and the vernacular, too. All this because “letters are the true and principal ornament of the soul,” and not only for courtiers.[44]

If Castiglione's pages appear to reverberate with echoes of medieval portraits of courtiers, an earlier humanistic text will also ring a bell for its remarkable specificity, while it helps us to tie the literature of courtliness to that of chivalrous love: it is L. B. Alberti's Ecatonfilea (1428), with its portrait of the ideal lover:

neither poor, uncleanly, dishonorable, nor cowardly . . . which will require prudence, modesty, patience, and virtue . . . ; studious of the good arts and letters . . .. Deft, physically strong, courageous, both bold and meek at the right time, poised, quiet, modest, given to wit and playfulness when and where it was fitting, he was eloquent, learned and liberal, loving, compassionate and respectful, cunning, practical-minded, and more loyal than anyone, excellent in courteousness, adept with the sword, horse riding, archery, and whatever similar sport, and expert in music, sculpture, and any other most noble and useful art, and second to no one in all such worthy activities.[45]

In his Ragionamento d'amore of 1545, Francesco Sansovino repeated these epithets of astuto and pratico in another lover's portrait: “of medium height, well to do, noble both by inner worth and by birth, versed in letters and music, . . . prudent, attractive, courageous, practicalminded and cunning, well-received and of loving disposition, affable, pleasing and sweet.”[46] We can readily note the persistence of so many specific terms.

On the verbal level we must not be deceived by the partial absence of the traditional moral terminology, replaced by Castiglione's personal nomenclature. It is significant that the term “courtier” was rendered as

curialis and aulicus (“man of the palace”) in Bartholomew Clerke's Latin translation of the Cortegiano under the title De curiali sive aulico (London, 1571, 1577, 1585, 1593, 1603). The Latin terminology was both more precisely connotative and more enduring. If it is true that the crucial term cortesia is missing, it should be evident that Castiglione's three key terms sprezzatura, grazia, and affettazione are recognizable reinterpretations of measure (G. mâze ), good bearing (like G. zuht ), and the opposite of reticence as part of mansuetudo —this last quality encompassing the “naturalness” that is part of the game of noble deportment, associated with the kind of dissimulation that we found, for example, in Gottfried's young Tristan. Ever since Quintilian and through the medieval period, urbanitas included elegant and witty speech, hence also facetia —and here we immediately think of the famous section of Cortegiano 2.42–83 on witty speech. Nor should we forget the presence of clowns or minstrels at Castiglione's court: besides being the traditional carriers of literature (mainly oral), they contributed that ingredient of courtly gaiety that we have seen among curial qualities as facetia and among courtly/ courtois ones as joi and solaz. The extensive treatment of wit and humor in speech (including facezie ) is part of this.

Though a neologism, sprezzatura is obviously close to the modest pose shrewdly displayed by the young Tristan at King Mark's court, when he coyly underplayed his extraordinary talents. Castiglione explains it further with the synonymous sprezzata disinvoltura, a nonchalantly poised self-assurance designed to impress the observer with the feeling that “the man masters his art so thoroughly that he can obviously make no mistake in it,” like the dancer who talks and laughs while he performs, seeming to pay no attention to his complicated movements (1.27). It is all part of the standards of external conduct, the mores (MHG síte ). The seeming disregard for behavioral technicalities, whereby we look like noble gentlemen rather than manual craftsmen or professionals, is not only an elegant attitude but the result of the fact that the courtier's instruction in the arts is, precisely, not professional, as Castiglione emphasizes early on.

Sprezzatura recalls the Nicomachean Ethics' rather ambiguous treatment of “irony” as the counterpart of boastfulness, somehow corresponding to Castiglione's opposition of sprezzatura/affettazione. For some critics the dissimulation that is inherent to both irony and sprezzatura is “a trick, . . . a discrepancy between being and seeming”; it seems to reveal “an attitude to class values that we must call aristocratic”: in Aristotle “the magnanimous man will have recourse to irony

in his dealings with the generality of men, the masses.” It also involves a complex, difficult, and risky balancing act: if we are caught dissimulating, our game will be over—like courtiers, diplomats, or orators in front of a jury.[47]

There are closer antecedents for this notion of an art that looks like nature. In his treatise on the managing of the household (De iciarchia ), L. B. Alberti advised his readers to handle important things

with much modesty joined with gracefulness and a certain gentlemanly air, so as to delight the observer. Such matters [requiring maximum concentration] are horseback riding, dancing, walking in public, and so on. Above all we must moderate our gestures and our bearing, the movements of all our person with the greatest care and with such thoroughly controlled art, that nothing will seem to be done with calculated artifice; whoever sees you must feel that this excellence is an inborn, natural gift.[48]

Similarly Castiglione:

Having long considered whence this grace may come, I find a most universal rule, to wit, . . . to eschew affectation as much as possible; and, to coin what may be a new term, to make use in everything of a certain sprezzatura that conceals art and makes whatever we do and say seem effortless and almost unconscious. I feel that grace derives above all from this: and this is because we all know the difficulty of things that are rare and well done, so that we tend to marvel at witnessing ease in such matters. Therefore we can say that true art is that which does not appear to be art; nor must we put our effort in anything more than in hiding it . . .. I remember having once read of excellent orators of antiquity, who . . . pretended not to have any knowledge of letters; and while dissimulating their knowledge.[49]

This gift of concealed art, echoing Ovid's Metamorphoses, remained a trait of noble behavior until at the court of Louis XIV Boileau defined it as the peak of art, calling it art caché (translation of Longinus's Ch. 22). We know that the same milieu had become accustomed to the identification of reason and nature or naturalness. The, shall we say, deceiving function of such fashioning of character through the appropriate use of misura and mediocrità lies in being not “like the others” but better than they, but without offending them and, we could add, without causing reactive “envy”: “he must strive to surpass all others in everything at least a little, so that he will be known as the best.”[50]

Alberti's antecedent to the supreme requirement of dignity, poise, and ease that Castiglione summarizes in sprezzatura can also be recognized in what has been called the “poetics of ease” (poetica della facilità ) with reference to the controversy over comparing Raphael's Olym-

pian style to the “difficulty” of Michelangelo's art. Alberti's De pictura (1435) had enjoined that the motions of the figures be “moderate and sweet, so that they will rather inspire grace to the onlooker than wonderment out of difficulty,” and that virgins, young men, or adults should all be represented as moving with strong but sweet gracefulness (“una certa dolcezza”).[51] The term and the concept were destined to enduring success. Merely six years after the appearance of the Cortegiano, Agostino Nifo da Sessa (ca. 1470—ca. 1540), the Aristotelian philosopher at Padua who was also known for his un-Platonic view that love is driven by sensitive appetite (De pulchro et Amore, 1531), published a treatise on courtliness (De re aulica, 1534, translated into Italian by Francesco Baldelli in 1560) where he advised spontaneity and naturalness but gave examples that sounded quite artful, so that, we can interpolate, he was teaching a Castiglionesque art that tried to look like nature.[52]

In sum, the ideal portrait encompasses the principal requirements of: nobility; military art (but only the basic principles, not the “mechanical” technical skills, and including the knightly art of horseback riding); knowledge of humanistic disciplines, including dance and music; and, as for mores, the sprezzata gracefulness of a second nature, in addition to that discretion that avoids or blunts envy and that sense of measure which avoids passing the mark. Since the Renaissance interpreted the traditional virtue of sapientia as essentially knowledge of literature, within the courtly frame of reference the traditional heroic symbiosis of fortitudo and sapientia became a binomium of arms and letters. (Of all Europe, Siglo de Oro Spain witnessed the most intensive and productive coupling of armas y letras.[53] )

The theme of knight versus cleric, miles an doctor, a matter of practical as well as theoretical choice, was destined to remain alive, as witnessed, for example, in Girolamo Muzio's Il gentiluomo (1564) and Annibale Romei's Della nobiltà (1586). But Castiglione no longer separates the two poles: he smoothly merges them into his ideal courtier, a refined military man, statesman, and, if called for, a man of the Church too, the way the medieval bishop had to be statesman and armed ruler in one. Duke Ercole of Ferrara had to implore his son, Cardinal Ippolito d'Este, not to doff his spectacular suit of white armor in order to go off to war against Louis XII of France on the side of Ludovico il Moro.

His sources, Castiglione avers in the prefatory letter to Miguel de Silva, are Plato, Xenophon, and Cicero (meaning Cicero's De oratore for the idealized image of the orator, but also perhaps the De officiis for

the moral portrait of the public man). To these models we must add Plutarch and Aristotle,[54] as evidenced by his numerous derivations from their texts. But we must not overlook relevant medieval ingredients, like the pre-humanistic medieval image of the pupil imitating the teacher: see Castiglione's statement that “whoever would be a good pupil must not only do things well, but must always make every effort to resemble and, if that is possible, to transform himself into his master.”[55]

The courtier's functional requirements include the traditional cardinal virtues. Although princes often “abhor reason and justice” (“alcuni hanno in odio la ragione e la giustizia” 4.7), it is the courtier's role to make them practice them in spite of themselves, together with fortitude, prudence (prudenza and discrezione ), and temperance (defined as harmony through reason).[56] In performing this difficult task, grazia must temper the severity of the philosopher and moralist, who would otherwise anger an impatient prince. The courtier thus becomes a subtle and dissimulating diplomat, indeed, the foundation of modern diplomacy.

Feeling that the closest specimens of the perfect courtier are his contemporaries, Castiglione protests against the nostalgic laudatores temporis acti who, as Dante and the court critics had traditionally done, use the courtly models to criticize contemporary moral decadence. The image of Castiglione as a nostalgic dreamer after good things irreparably lost is a rather Romantic way of reading him. Pride in the ripeness of the present is Castiglione's primary mover. Nevertheless, the courtier lives in a state of tension in the book as well as in the real life of those years of supreme uncertainty: while trying to save his neck, he must also strive to serve his prince in such a way as to achieve the good of the state and of his subjects. The virtù di cortegiania was conceived by Castiglione as a means to a moral political end.

While discussing Petrarca's position within the modes of literary transmission, I stressed the relative novelty of the early Italian poets' concern for a standardized language, pointing out the ideal connection between such concerns and the nature of life at court. Castiglione's position on the Questione della Lingua was in harmony with his perception of the nature and role of the courtier class, which was to be the most unified and responsible segment of Italian society. The active debate on the national language, destined to have a prolonged impact in many countries,[57] started precisely at Italian courts (Rome, Urbino, Mantua, and Milan).[58] It was not only natural and fitting, but supremely logical that in that setting the question of a standard means of

communication would be seen from a vantage point of administration and official acts rather than literature and high culture, especially since courts were interregional and courtiers, moving about a lot, had to communicate in some lingua franca.

A common language was of paramount importance among people who daily could witness the tragic consequences of the lack of any other strong national bond. Calmeta, cited by Castiglione, and a denizen of all the courts just mentioned, was probably the originator of the theory of a lingua cortegiana, with a book called Della volgar poesia (ca. 1503, dedicated to the Duchess of Urbino) that is now lost.[59] Mario Equicola (1470–1525), another courtier and secretary to the Marquises of Mantua, proposed the usage of the Roman Curia, rejecting current spoken Tuscan as plebeian.[60] So did Gian Giorgio Trissino (II Castellano, 1529), the major theorist of the “courtly language,” while one more proponent of this thesis, Piero Valeriano, found current Tuscan wanting on account of excessive regionalism. Clearly, Castiglione had company, but Bembo's doctrine of Trecento Florentine prevailed, thanks to the prestige of the Three Crowns. Bembo had plenty of allies in all camps in his distaste for anything that smacked of popular parlance, which contributed to downgrading Dante and elevating Petrarca and the expurgated Boccaccio to the status of canonical models. The aesthetic criterion played a dominant role in rejecting from the literary lexicon any part of the language that was not “fitting and decorous”—another echo of established courtly behavioral patterns. Beyond language itself, the new classicism canonized decorum above all.

The issue of a common language was a central one in the life of the courts and it remained so in other countries, too. The emergence of French as the “universal language” of the civilized world from the end of the seventeenth to the beginning of the nineteenth century and beyond was a court phenomenon. Intellectuals, scientists, and diplomats read and wrote French (as well as Latin) all over Europe, but it was only the court societies, from Lisbon to St. Petersburg, that made wide and regular use of spoken French.

The special use of language at court was affected by the style, terminology, and moods of Petrarchist/Platonic love as a way of feeling, speaking, behaving, and living. On its highest level, that philosophy of love had become a form of mystical rapture, and indeed the Cortegiano ended in an emotional climax with Bembo's speech on Platonic love. It was a religion for an age of religious skepticism. The fact that Petrarca

fitted into this need for a Platonic idealism was another reason that Laura became the universal model of the beloved. No room was left for Dante's Beatrice, who was not only sublime and divine but lead directly to God Himself. Platonic and courtly love found a major authority in the learned courtier-philosopher Mario Equicola thanks to his successful treatise Libro de natura de amore, published in the vernacular in 1525 and 1526 (Venice) as a translation of the Latin original of 1495. Equicola perceptively discriminated between the ancient way of loving and writing about love and the Provençal way of, as he put it, “concealing through courteous dissimulation any lustfulness in their affections.”[61] Platonic love was the inspiration of another authoritative Ficinian philosopher of those years, Leone Ebreo (Dialoghi d'amore, Rome 1535).

Should we still wonder how Bembo's lengthy digression on Platonic love squares with the main theme of the Cortegiano, another answer might be that it fits as a conclusive moment of mystical exaltation filling the role of joi in fin'amor, with which it has in common the striking feature of unsatisfied longing for a superhuman reward: courtly love itself functioned as an ideal form of training for service to the lord or prince. Bembo's speech is thus at the intersection of courtliness and courtesy, while courtly love was chivalry's poetic expression. Auerbach (Mimesis 122) recalled Castiglione for his fusion of Platonism with the courtly ideal but concluded that this Platonism was little more than “a superficial varnish,” whereas the true role of courtly culture, “with the characteristic establishment of an illusory world of class (or half class, half personal) tests and ordeals,” remained “a highly autonomous and essentially a medieval phenomenon.” The preceding has shown somewhat closer connections between Renaissance developments and an operative medieval heritage. It bears recalling that Ficino had adapted medieval techniques, including the special intellectual devices that, as we have seen, Petrarca inherited from the troubadours. Furthermore, his sophisticated and somewhat sophistical mysticism of love was the instrument whereby he created at the Medici court his own inner court or “academy” of intellectuals who expressely bound themselves to one another by this Platonic love. P. O. Kristeller has reminded us that Ficino is the only thinker of modern times who tried to found a philosophical school on both an intellectual and a moral bond between teacher and pupils—this bond being his successful brand of “Platonic love.”[62]

Ferroni and Quondam, among others, have stressed (perhaps over-

stressed) the “laceration” and the forced “suture” that occurs between book 4 and the other three books of the Cortegiano.[ 63] Other critics have speculated that Castiglione, having described a self-sufficient court that seemed elegantly aimless and useless (to the “subjects”), decided that his courtiers needed a redeeming social and political function, so he put their rare qualities and talents to the good use of impressing the prince and making him receptive to good advice.[64] But rather than being a possible afterthought, perhaps this “suture” reflects a real duality in western civilization. The gentleman—useless, as we shall see, for a Machiavelli—remained for a long time an object of attention, admiration, and emulation, a center of real power, hence a being with a social function, even when economically unproductive. This bipolarity lived on in literature as it lived on in society. The foregoing exposition should have made clear that this tension between “service” and personal dignity, being a lord's liegeman and at the same time one's own master, is not a unique problem for Castiglione, but the common predicament of the medieval and Renaissance knight and courtier.

We might also wonder whether this suture or inner tension was not analogous to the tensions we found in the medieval epics and in the chivalric romances, especially between, on the one hand, the image of an Arthurian court that was divorced from social and moral reality, and, on the other, the poets' (Chrétien, Hartmann, Gottfried, or Wolfram) need to find a useful moral purpose for wandering knights. Far from being conclusive and satisfied codifications of a self-sufficient imaginary world, those poems were live attempts to frame and resolve open socioethical problems through the fiction of beautiful tales. None of those authors, from Chrétien to Castiglione, felt they were closing a discourse by providing definitive answers. Hartmann, for one, was not even sure he wanted to go on lending allegiance to his chosen genre, as his about-face, later to be once again reversed, showed in the writing of Gregorius.

What some observers of Castiglione's Courtier have perceived as a contradiction between the real forces of court life and the need for moral satisfaction is in fact a noble effort to reconcile reality with moral imperatives. In Gottfried's Tristan and Wolfram's Parzival we noted a tense confluence of sublime aspirations to moral aesthetic perfection and a realistic perception of civilizing forces at work. Tristan was at the same time, in an uncanny combination, a hero of purity and an artist of survival. Somewhat similarly, the myth of Prometheus and Mercury in

Il Cortegiano 4.11 contains in a nutshell Castiglione's concepts of “viver moralmente,” “sapienza civile,” “virtù civile,” and “vergogna”: Jove symbolizes an aboriginal ruler, and Mercury an educator through eloquence and learning, this process involving progress from (individual) art to (collective) civilization.[65] Like Tristan, the courtier too has to face the divergence between full and free development of personal qualities and service to society.

In a passage that reminds us of King Mark's advice to Tristan in Gottfried's Tristan (8353–8366), Castiglione presents a dialectical view of the role of courtly vices in setting off courtly virtues:

Evil being the contrary of the good and vice versa, it is almost necessary that by the law of opposition and compensation the one sustain and strengthen the other, so that if one decreases or increases, the other must increase or decrease, since every term is not without its opposite. Who does not know that there would be no justice in the world if there were no wrongs? No magnanimity, if none were pusillanimous? . . . No truth if there were no falsehood? Hence Socrates well says, according to Plato, that he marveled that Aesop had not made up a fable in which he imagined that God, realizing the impossibility of combining pleasure and pain, had joined them by their extremities, so that the beginning of one was the end of the other. Indeed, we can see that no pleasure can ever be truly appreciated unless it is preceded by some displeasure . . .. Therefore, virtues having been given to the world through grace and gift of nature, by immediate necessity vices became their companions, according to that law of chained contrasts. So, as soon as either one grows or abates, perforce the other must also grow or abate.[66]

In this remarkable piece of pre-Hegelian dialectic the existence of opposites is explained as a psychological and ontological necessity, an answer to the existential question mark that had troubled every moralist from Job through Augustine and on, about the justness of divine providence and the reason for the existence of evil. Castiglione even adds a theoretical insight that is tantamount to a doctrine of the balance of opposites—a doctrine which would continue to be popular among moralists and produce a lively debate in the late seventeenth- and eighteenth-century theory of bonheur, especially in France.[67]

Another feature the Cortegiano shares with chivalric literature is the element of play in the form of contests and formal games—not only in the first chapters, where various typical forms of entertainment are proposed before selecting the game of portraying the ideal courtier, but in the postulate that court life must be entertaining throughout, even in the conduct of serious business.[68] We have noted how in the romances,

too, all contests, like tourneys and hunting parties, were perceived as exquisite games even when they had a serious and dangerous side, as they often did. The fourteenth-century Sir Gawain had carried this aspect of chivalry to extreme consequences.

Castiglione's reception is a signal case of evolution in the form of productive dislocation or even distortion: a work that was a continuous question mark, a problematic meditation on something dynamic, in fieri, to be discussed dialectically because it was still moving and partly undefined, an act of life and a fervent, partly nostalgic reminiscence, was happily misread into the static canonization of a supposedly perfect state, a universal model. Quondam (19) gives a concentrated description of this reception: the work assumed (my translation) “the proportions of an anthropological manifesto (a true cultural typology, a generative model), . . . which activated, above all, other grammars . . . , e.g., that vast body of treatises on dance, games, duel, hunting, horse riding, dressing, eating, being a secretary, etc.”—all literature which was related to the life of the court, explicitly or implicitly.

In conclusion, the specificity of the Cortegiano vis-à-vis the more generic ethics of other treatises on conduct and princely education lies in a combination of military aptitudes, humanistic training (liberal arts), and behavioral patterns—all to be directed to the civic function of influencing the prince by winning his trust and favor. It is this combination of factors that finds its specific antecedents in curiality and courtesy, if we understand the latter as a combination of martial arts and moral purpose with a psychologically strategic method of pleasing refinement. Of course one must take into account the more secular setting of the courtier vis-á-vis the curial cleric (to take the other extreme of the medieval parable). But even here we must bear in mind the closeness of high ecclesiastical spheres to knightly milieus at the chronological beginning of our story—since the bishops were often temporal rulers and warriors as well—and then, at the other end of it, the closeness of Renaissance courtiers to high ecclesiastical milieus, as personally witnessed by the protagonists of the Cortegiano and its Roman counterpart, Cortesi's De cardinalatu.

The Cortegiano was the lofty expression of the humanistic intellectuals' effort to find their place in a changing society at the closest point to the peak of power. The ensuing “curialization” of the courtier was an implicit acknowledgment of defeat, since the ideal of a responsible lay counselor to the prince had hardly been attained. Ironically closing

the circle from its medieval beginnings, the courtier was soon to become either a curialis or a ministerialis as a minister, secretary, or bureaucratic functionary to a prince.

Machiavelli (1469–1527) and the Court as Artifice

We have begun to see better the complexity and ambiguity of social allegiances in Renaissance Italy. I shall now turn to the telling case of Machiavelli in order to show that this so consistently Florentine observer of human behavior is no exception to the fact that even in the most bourgeois environments the aristocratic ideologies that had dominated medieval literature and thought continued to affect perspectives and judgments.

Castiglione's perception of moral values in the world of politics has often been contrasted with Machiavelli's. Patently, Machiavelli's “realism” clashes with his contemporary's idealizing will to form a “perfect courtier” who embodied all that was most admirable and morally respectable in a member of the governing élite. For Machiavelli, we all know, the ordinary moral virtues are more a hindrance than a help to effective political action. Although the well-endowed statesman is conscious of the need to appear virtuous, he is able and ready to depart from moral rules when it is expedient to do so, since he aims not at the good but at the useful. Castiglione was not prepared to see how the good and the useful could be separated. But more relevant for us is how, beyond personal attitudes, both writers mirror the reality of a shattering crisis, involving the agonizing realization that the fragmented individualism of Italian political behavior had been a high price to pay for the splendors of the Renaissance. When foreign armies supported by socially unified national states appeared on the scene, the impossibility of a common policy among the Italian states spelled general ruin. The spectacle of men in unstable governments scrambling for improvised means to save their skins and privileges in the wars of 1494–1559 revealed not only the weaknesses of social and political structures but also the decisive nature of the basic moral imperative: the fateful choice between “good” government in the interest of all subjects and expediency in preserving personal or group privileges.

Both Castiglione and Machiavelli had to face the alternative of justice or power, deep honesty or hypocritical preservation of form, virtue as moral value or “virtue” as, in Machiavelli's peculiar acceptation,

efficient inner energy. Along with the traditional virtues of private morality, the “curial” ethic was now revealing more clearly than ever both its relevance and its profound ambiguity. The questions and the choices were: leading or seeming to lead, governing or oppressing and exploiting.

The “Florentine secretary” was particularly disinclined to appreciate the role of the social layer that made up the courts. As a true citizen of bourgeois and republican Florence, he did not hesitate to define the gentiluomo as one who lives abundantly off revenues without work, “senza fatica”; hence he is inherently outside that true “vivere in civilitá” that Machiavelli identified with the free cities, and is particularly dangerous when he possesses castles and dominates working people who have to obey and serve (Discorsi 1.55).[69] That “vivere senza fatica” that irked Machiavelli as parasitism unwittingly echoes Castiglione's image of the gentleman whose most impressive behavioral feature is grace in concealing his artfulness, so that he seems to do whatever he does without effort and almost without thinking: “senza fatica e quasi senza pensarvi.” Besides being a supreme mark of elegance, that easy manner was also a correlative of “living without effort” on the economic level. The very abstractness and unproductiveness of knightly games in the literature of the romances was a necessary sign of the knights' “nobility”—not quite without effort, to be sure, but without “use.” Even in the epics there were as many tournaments and games as real battles.

To Machiavelli, military exercises were justifiable neither as elegant games nor as a form of superior service to God, but only as necessary means to political ends—a shift that even the Church was compelled to accept. Hence his little regard for the usefulness of the knightly class extended to the military sphere, where he held infantry more valuable than cavalry. Compare, besides his Arte della guerra, Discorsi 2.18, “come si debba stimare più la fanteria che i cavagli,” where he blames the condottieri for a special interest in keeping armies of horsemen and, typically, appeals to the Roman model, where infantry had the major role. He cites the modern example of the battle of July 5, 1422 at Arbedo near Bellinzona, where Carmagnola, acting for Filippo Visconti, managed to prevail against the Swiss infantry only after dismounting all his horsemen.

Just as he distrusted courtiers, noblemen, and knights, Machiavelli appreciated the potential virtues of “the people” (la moltitudine, he says, indiscriminately) in terms as explicit as were ever heard before or

long after. One of his most rewarding essays, Discorsi 1.58, is titled “La moltitudine è più savia e più costante che uno principe.” There he takes a firm stand against public opinion, “contro alla commune opinione,” including, mind you, the hallowed authority of his Livy, by protesting that the people are more prudent, more stable, and of better judgment than the prince: “dico che un popolo è più prudente, più stabile, e di migliore giudizio che un principe.” They are also more reliable in their choice of elected public officials, usually worthier men than the choices of absolute rulers: “Vedesi ancora nelle sue elezioni ai magistrati fare di lunga migliore elezione che un principe.” The people will never be persuaded to put in office a corrupt and infamous person, something princes do easily. In sum, popular governments are better than despotic ones: “sono migliori governi quegli de' popoli che quegli de' principi.” If, as was the thesis of Il Principe, princes are better at organizing new states, popular governments are superior at maintaining a state once organized: “se i principi sono superiori a' popoli nello ordinare leggi, formare vite civili, ordinare statuti ed ordini nuovi, i popoli sono tanto superiori nel mantenere le cose ordinate.” The superior wisdom of the popolo is reaffirmed in Discorsi 3.34. We have come a long way from the hateful distrust of the vilain: even if Machiavelli's close paradigm was bourgeois Florence, which did not include peasants as citizens, his universal model was republican Rome, with plebeians a majority among the voting population.

All this notwithstanding, it is particularly interesting in our context, and it may come somewhat as a surprise, that in a literal sense Machiavelli's ethical framework owed more to the courtly tradition than to the classical and Christian canons. Analyzing the virtues that are profitable to the prince in the ethical section of Il Principe (chaps. 15–24), he criticizes above all the notions of liberalità (all of chap. 16), generosità, and lealtà. The choice and sequence of qualities should have a familiar ring to us. When Machiavelli advises the prince to be a “gran simulatore e dissimulatore” (chap. 18), we are reminded once again of the familiar courtly environment, including the literary one of Tristan.

Machiavelli's review of the prince's moral traits begins with this listing (chap. 15):

alcuno è tenuto liberale, alcuno misero . . . ; alcuno è tenuto donatore, alcuno rapace; alcuno crudele, alcuno pietoso; I'uno fedifrago, I'altro fedele; I'uno effeminate e pusillanime, I'altro feroce et animoso; I'uno umano, I'altro superbo; l'uno lascivo, l'altro casto; l'uno intero, l'altro astuto; l'uno duro, l'altro facile; l'uno grave, l'altro leggieri; l'uno relligioso, l'altro incredulo, e simili.

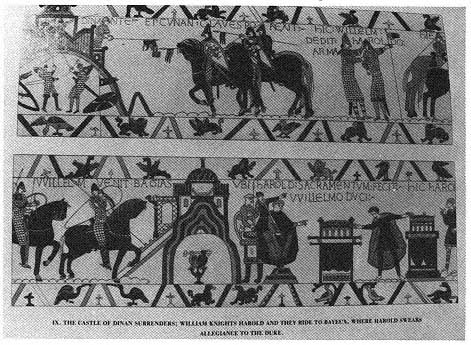

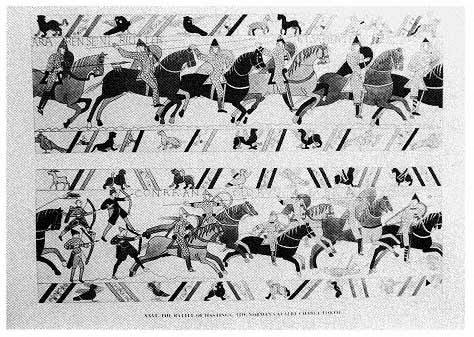

1–2.

William of Normandy Knights Harold of England; The Battle of Hastings: details

(sections 21 and 58, last) of the Bayeux tapestry (ca. 1073–1083).

Courtesy of the Town of Bayeux.

3.

Ruins of Castle Aggstein on the Danube, Austria. A point of encounter for many

troubadours.

Courtesy of Austrian Tourist Office, New York.

4.

Imperial Palace in Goslar, Germany.

Courtesy of German Information Center, New York.

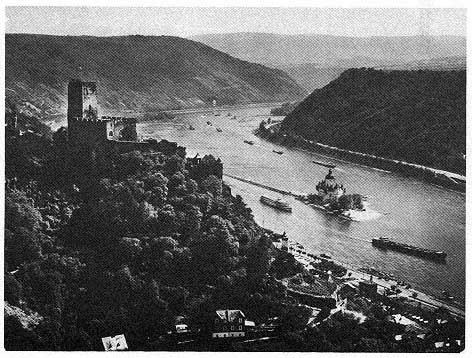

5.

Castle Gutenfels on the Rhine.

Courtesy of German Information Center, New York.

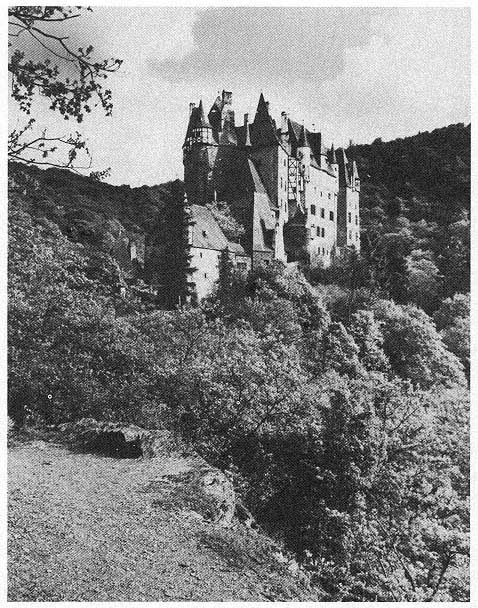

6.

Elz Castle, near the Moselle River.

Courtesy of German Information Center, New York.

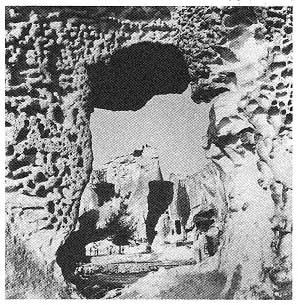

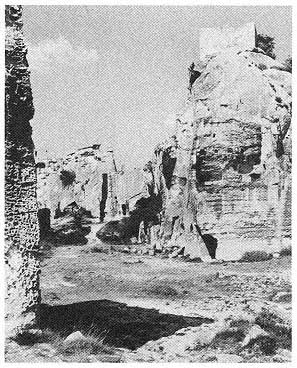

7–8.

Two views of ruins of Les Baux-de-Provence, a leading

Provençal feudal court carved out of the rock in the

thirteenth century, destroyed by order of Richelieu

as a focal point of feudal resistance to the centralized

monarchy.

Courtesy of French Government Tourist Office, New York.

9.

Giant Roland in front of Bremen City Hall. Erected in 1404 by the burghers in defiance of

the archbishops' authority, using chivalric ideology as a symbol of communal freedom.

Courtsey of German Information Center, New York.

10.

Jan van Eyck (fl. 1422–1441),

The Last Judgment. Tempera and

oil on canvas. The angel-judge

appears in the garb of a knight.

Courtesy of the Metropolitan

Museum of Art, New York,

Fletcher Fund, 1933 [33.92b].

11.

Pol de Limbourg, The Fall of the Rebellious Angels

as knights in armor. Les très riches Heures du Duc de

Berry, Musée Condé, Chantilly. Courtesy of Musée

Condé/Art Resource, New York.

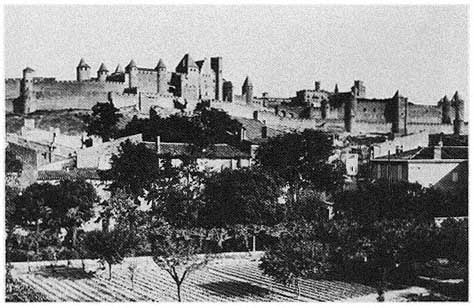

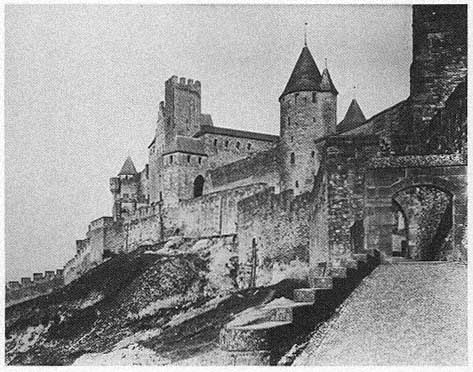

12–13.

Two views of Carcassonne. Outstanding example of medieval military architecture and

planning of a fortified town that coincided with the castle and an extended lordly court.

Courtesy of French Government Tourist Office, New York.

14.

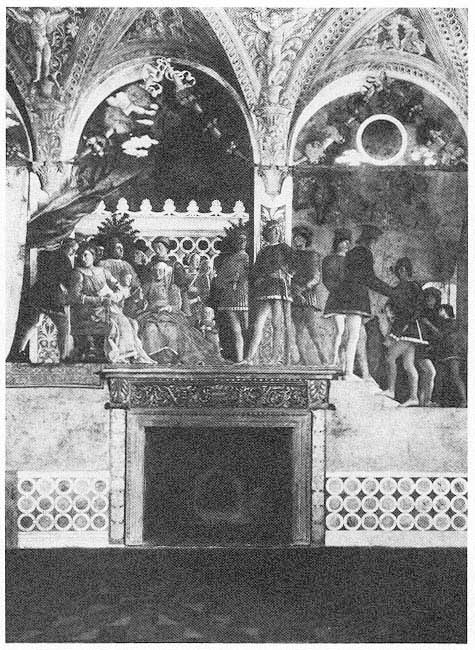

Camera degli Sposi, frescoes by Mantegna, with Ludovico Gonzaga consulting his

secretary Marsilio Andreasi (1465–1474). Ducal Palace, Mantua.

Courtesy of Scala/Art Resource, New York.

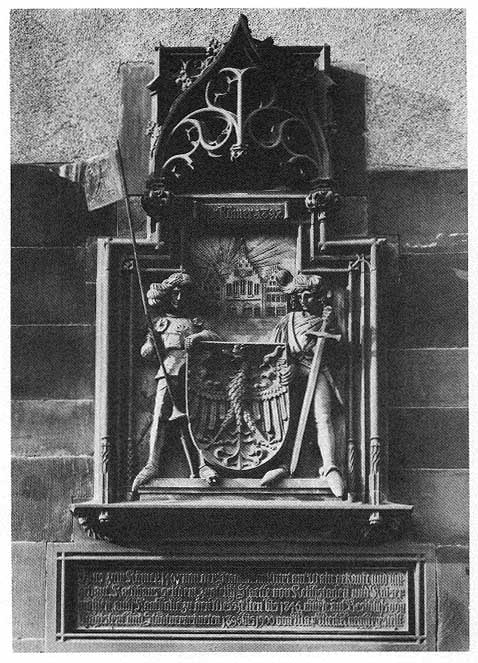

15.

Knights in the shield of the City of Frankfurt on the Römer, 1404.

Courtesy of German Information Center, New York.

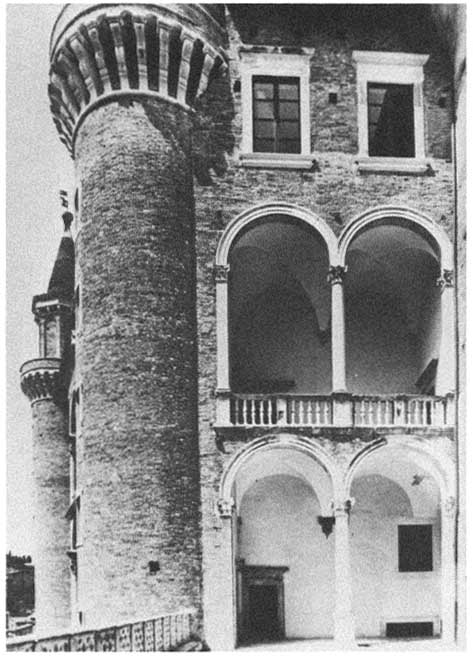

16.

Corner of Urbino Palace, built under Federico da Montefeltro, ca. 1480? Note blending of

medieval and Renaissance features.

ANSA photo from Italian Cultural Institure, New York.

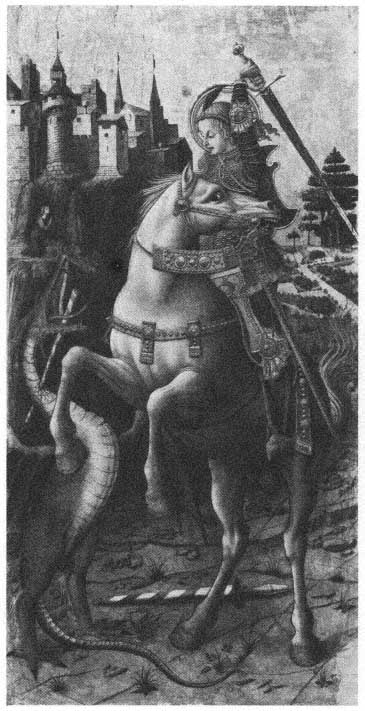

17.

Carlo Crivelli, St. George and the Dragon. A saint i knightly garb,

or a saintly knight: anothr example of the coupling of the religious

and profane.

Courtesy of the Isabella Stewart Gardener Museum, Boston, and

Art Resource, New York.

18.

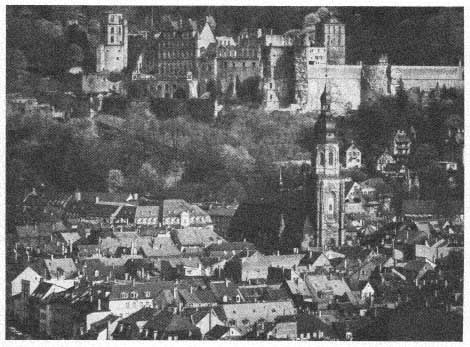

Castle of Heidelberg. Courtesy of German Information Center, New York.

19.

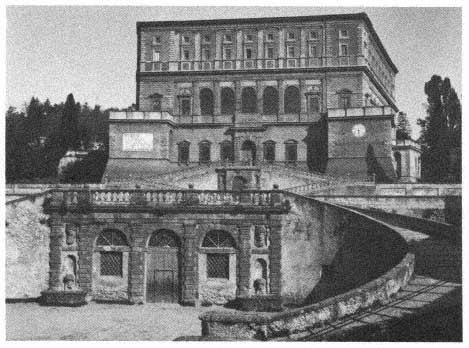

Jacopo Vignola, Palazzo Farnese (1550–1559), Caprarola (Viterbo).

Courtesy of ENIT , Italian Government Travel Office, New York.

20.

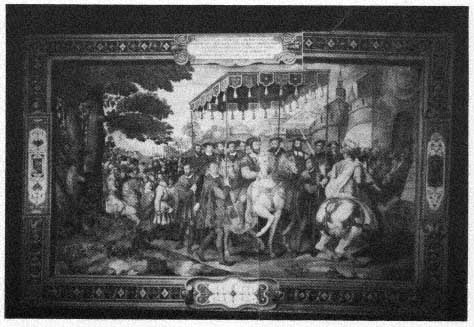

Palazzo Farnese, Caprarola, Sala dei Fasti. Pius III and

Charles V in battle against the Lutherans.

Courtesy of ENIT , Italian Government Travel Office, New York.

21.

Palazzo Farnese, Caprarola, Sala dei Fasti. Francis I welcoming in Paris the Emperor Charles

V accompaind by Cardinal Allessandro Farnese (Taddeo Zuccari and helpers, 1562–1565).

Courtesy of ENIT , Italian Government Travel Office, New York.

22.

Lorenzo Bregno, St. George and the Dragon, from the facade of Buora's Dormitory, Isola

di San Giorgio Maggiore (Venice).

Courtesy of Giorgio Cini Foundation, Venice.

23.

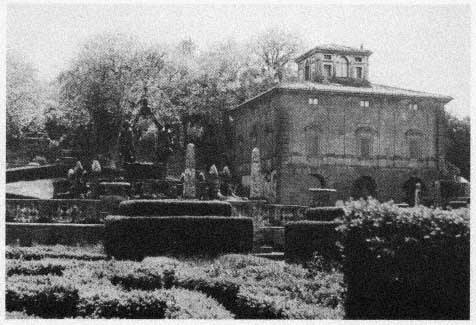

Villa Lante, Bagnaia (Viterbo).

Courtesy of ENIT , Italian Government Travel Office, New York.

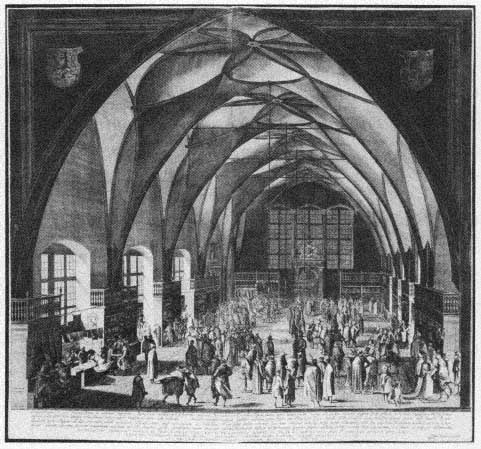

24.

The Great Hall of the Hradshin Imperial Castle, Prague, engraving by Aegidus Sadeler,

1607. The court as a center of wide-ranging socail and even commercial activities, including

trading in art works.

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick fund,

1953 [53.601.10(1)].

Is this not a list of chivalrous qualities, positive and negative? It seems clear that Machiavelli did not have in mind some moral treatment of classical or Christian virtues but one of the kind that would be at home ina “mirror of princes” based on the chivalrous ethic.

Let us now take another look, reordering the pairs which Machiavelli inverts five times. He opposes liberality to miserliness, generosity to thievery, pity or mercy to cruelty, loyalty to treachery, manly spiritedness (Fr. franchise ) to duplicity (a courtly though not a courtois virtue), indulgence to hardness, dignity to plainness, and respect for religion to indulgence to hardness, dignity to plainness, and respect for religion to irreverence. The “great soul” that is made to loom large among the valuable strategic qualities (chap. 21) derives from both classical and medieval ethics, as we have observed, and Ferdinand the Catholic is declared to be its most striking example. The reference to greatness of character or soul that was implied in the animoso (contrasted to pusillanime ) is fully developed in chapter 21, where grandezza (grande imprese, rari esempli ) is commended as a way of winning fame (egregius habeatur in the Latin title rubric) and conquering the admiration of subjects and rivals. Once again, Machiavelli had the ancient Romans in mind, but the belligerent policies he regarded as a sign of vitality in the state and an almost biological law of politics had been a trademark of the chivalric ethic. Aristotle's megalopsychia was destined to play a continuous role through the Middle Ages and humanistic education as well, including, in the new context of militant Christianity at the service of the Church, the Jesuit schools. The ideal of magnanimity would remain part and parcel of Jesuit pedagogy, since Ignatius of Loyola (himself a heroic professional soldier before his conversion) characterized the true Christian as a militant soldier of Christ, the new miles Christi.[70] Machiavelli's heroic view of political leadership falls within this continuous tradition.

Indeed, at opposite poles, as it were, both the secular thinking of a Machiavelli and the planning of educational patterns for the Counter-Reformation disclose the presence of the combined ideologies of chivalry and courtliness. As an eloquent example of the latter I shall mention only the case of the most important college for the nobility in Italy, that of Parma. The Duke of Parma, Ranuccio I Farnese, took pains to ensure the functioning of the Ducal College for the Nobility (1601) as a bulwark of his policies of firm orthodoxy within a program of outspoken loyalty to the Roman Church and to Spain. It is interesting that in so doing he spelled out the guiding principles for his college in terms of the ideologies of chivalry and courtliness. Its pupils were to be in-

structed not only in piety and letters—which was also the explicit program of all Jesuit educational institutions—but also “in those other exercises that are proper to the Nobility and necessary to Knights,” namely dance (a healthy sport and a social grace), mathematics (for military engineering), fencing (for the use of arms in the service of God), and horseback riding.[71] The College was soon entrusted to the Jesuits (1604–1770).