| • | • | • |

Letter XXIII

Dear Sir,

The principal rural sports of the people of Indostan, are hunting and hawking: they purchase hawks and other birds of prey from Persia, which are taught to fly at all manner of game.

The Soubahs and other great characters of the country, find much amusement in the combats of wild beasts. The elephant often encounters the elephant, with a rider mounted on each, to manage them, on a larger space of ground paled in with bamboes to keep off the crowd of spectators: they attack each other with great fury, for several hours, till one of them with its rider, is either killed or disabled. The buffaloe commonly engages with the tyger, and, though ferocious the latter, frequently worsts his quadruped antagonist. It would be endless to enumerate the many diversions of this kind, which consist of various animals attacking each other or combated by men who risque their lives in such dangerous enterprizes.

Among the joyous inhabitants of this country, there are some content to live on what is just sufficient to supply human necessity: which is strictly pursuing the idea of Goldsmith, that elegant writer, who observes in his Edwin and Angelina,

Man wants but little here below, Nor wants that little, long.

They acquire a support, by administering to travellers as they journey along the roads and highways, a chilm, or pipe of tobacco, for which they receive a small gratuity. The rich and poor, sometimes, promiscuously mingle together, and often partake of the same refreshment.

At Muckenpore [Manikpur], a small village sixty miles from Belgram, is the resort of a number of Faquirs, from Delhi, Oude, and the neighbouring provinces. Hither the pious natives flock, to bestow their charity on these holy men, and think it a kind of religious humanity, highly acceptable to their God, to confer their benefactions on his faithful servants.

From the prayers of the Faquirs, great blessings are expected, and many calamities thought to be averted, as they obtain the reputation of sainted martyrs, by torturing their bodies, and suffering a variety of punishments, by way of penance, during this earthly pilgrimage. Some pierce their flesh with spears, and drive daggers through their hands: others carry on their palms, for a length of time, burning vessels full of fire, which they shift from hand to hand: many walk, with bare feet on sharp iron spikes fixed in a kind of sandal: several of their order turn their faces over one shoulder, and keep them in that situation till they fix for ever, their heads looking backward: another sect clinch their fists very hard, till the nails of the fingers grow into the palms, and appear through the back of their hands, and numbers, who never speak, turn their eyes to the point of the nose, losing the power of looking in any other direction. These last pretend to see what they call the sacred fire. Strange as this austerity may seem, if accompanied with purity of intention, it must be considered by the unprejudiced, as less offensive to the Deity, than the indulgence of the passions: though man be not forbid to enjoy the good things of this life, yet an abuse of that enjoyment, which evinces his ingratitude to Heaven, is punished even here below, by wasting the ungenerous being to an untimely grave—but he who foregoes the pleasures of a fleeting period, through an expectation of permanent happiness, and suffers temporary torture in order to obtain endless bliss, with a mind all directed to that great Power who gave him existence, must, notwithstanding the ridicule of the world, meet with a more favourable sentence at his awful tribunal.

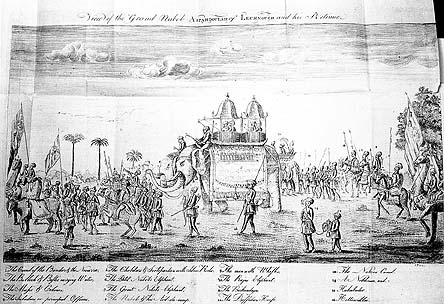

Not long before our departure from Belgram, we were honoured with a visit from the Nabob Aspa-doulah, accompanied by General Stibbert, his Aid-du-Camps, and other Officers of distinction, who met him on the way, in his usual style of grandeur, mounted with his Nobles, on an elephant richly caparisoned, and attended by his numerous train of Burkendaws, Chopdars, pages, &c. and a native band of music to enliven the procession, of which the annexed plate will give you a more perfect idea, than this description [see figure 3].

His entry through Belgram was announced by the beating of drums, firing of cannon, and other marks of military honour. After a repast at the General's, he retired to a large decorated tent erected for him, which covered almost an acre of ground; adjacent to his, others were pitched for his attendants.

The day after his arrival, our Commander in Chief issued his orders to prepare for a review. Early next morning, one regiment of Europeans, six of Seapoys, two companies of artillery, and one troop of cavalry, amounting in all to about seven thousand, were in perfect readiness on the wide plain. The Nabob on his elephant, in company with the General, passed the lines. Shortly after, the former descended from the back of the unwieldy animal, and mounted a beautiful Arabian horse, on which he received the salute of the Officers. Colonel Ironside ranged the troops in the following order: the cavalry were placed on the right and left wing; three regiments of Seapoys on each side next to them; and the European infantry in the centre. At first, they were all reviewed in one body, and afterwards formed different corps, observing the most exact discipline and regularity in their various evolutions, which gave much satisfaction to the General, Officers, and numerous spectators. Aspa-doulah, in particular, was exceeding pleased with the beauty and order of our tactics, and expressed his approbation in the terms of that lively kind of gratitude arising from a high sense of received pleasure. After the review, a breakfast was prepared for him, during which, the artillery continued to salute him with their cannon. His fare was served up by his own servants, as he could not touch any thing from the hands of a Christian, consistent with the duties of his religion: however, to shew his politeness, he sat at the same table, with our Officers of rank, and having remained a few days in the camp, returned to his own territories.

Figure 3. View of the Grand Nabob Aspahdoulah of Lechnough and his Retinue (Mahomet, Travels, Letter XXIII).