3. Dean Mahomet in Ireland

and England (1784–1851)

| • | • | • |

Dean Mahomet Enters Cork

Arriving at Cork late in 1784, twenty-five-year-old Dean Mahomet created a new life for himself. Through his patron, Godfrey Evan Baker, he gained access to the Anglo-Irish Protestant elite but he stood separate from them in origin, color, and culture. Nor did he fit among the colonized Catholic Irish peasantry. A few other Indians passed through or lived in Cork: Indian sailors, servants, wives, and mistresses, their Anglo-Indian children, and even the occasional Indian dignitary. Whatever relationships Dean Mahomet may have had with these other Indians, his situation remained quite different from any of theirs. Yet he quickly made a distinctive place for himself in Cork. He soon married a woman from a Protestant Irish gentry family. His literary achievement, Travels, received the endorsement of hundreds of Ireland's leading citizens, proof that they regarded him as a man of culture. Yet he remained someone quite apart from Irish society at the time.

When Dean Mahomet and his patron Baker reached Cork, Baker immediately assumed a prominent place in elite society. The Bakers stood as an established landholding clan, one of the pillars of the Protestant Ascendancy in southeast Ireland. His father, Godfrey Baker, had made himself a wealthy merchant in Cork. The city fathers had already elected the senior Baker to most of the important offices in Cork including Burgess, Mayor, Sheriff, and Water Bailiff.[1] Godfrey Evan Baker, within a year of his return, married the Honorable Margaret, second daughter of the Commander-in-Chief of Munster, Lieutenant General Lord Baron Massey (1700–88).[2] Godfrey Evan Baker's wealthy marriage added to whatever fortune he brought back from India. Dean Mahomet undoubtedly benefited from the Baker and Massey connections.

Soon after his arrival in Cork, Dean Mahomet began to study (under the Bakers' sponsorship) to advance his education. He particularly cultivated his knowledge of English language and literature. As clearly illustrated by the rhetoric and content of Travels, he mastered the classically polished literary forms of the day, complete with poetic interjections, erudite allusions, and classical quotations in Latin. Occasional poetry remained very much a part of the cultured life of some of the elite of Cork, reflected in the “Poet's Corner” found in nearly every newspaper. Much of this poetry was published anonymously; some liberally imitative of more established poets. We can never know if Dean Mahomet himself contributed his own verse to the “Poet's Corner,” but the unattributed poetry he included in his Travels is typical in style, content, and quality of such work.

In 1786, the same year Godfrey Evan Baker died, Dean Mahomet eloped with a teenage woman student, ![]() Jane

Jane ![]() Daly.[3] Suggestion of the haste or desire for privacy of this marriage comes from their decision to post a bond with the church where they were married rather than have the banns read for weeks previously from the pulpit, as was customary. This substantial bond would then indemnify the church should the marriage prove illegal. Any wedding between a Protestant and a Catholic was unlawful at this time in Ireland, with the officiating clergyman held responsible. Although Dean Mahomet must have already become a member of the established Protestant Church, we can imagine a lingering doubt in the mind of the clergyman who performed the wedding of this unusual couple, particularly since they had eloped. The substantial wedding bond also testifies to Dean Mahomet's own comfortable financial position: he either owned considerable capital or he had sufficient credit to borrow it for such a personal undertaking as his elopement. The newly married couple seem to have been accepted by Cork society, suggesting that Dean Mahomet's marriage to

Daly.[3] Suggestion of the haste or desire for privacy of this marriage comes from their decision to post a bond with the church where they were married rather than have the banns read for weeks previously from the pulpit, as was customary. This substantial bond would then indemnify the church should the marriage prove illegal. Any wedding between a Protestant and a Catholic was unlawful at this time in Ireland, with the officiating clergyman held responsible. Although Dean Mahomet must have already become a member of the established Protestant Church, we can imagine a lingering doubt in the mind of the clergyman who performed the wedding of this unusual couple, particularly since they had eloped. The substantial wedding bond also testifies to Dean Mahomet's own comfortable financial position: he either owned considerable capital or he had sufficient credit to borrow it for such a personal undertaking as his elopement. The newly married couple seem to have been accepted by Cork society, suggesting that Dean Mahomet's marriage to ![]() Jane

Jane ![]() may have enhanced his social status. Nonetheless, he remained too distinctive to assimilate fully into the Protestant Irish elite around him.

may have enhanced his social status. Nonetheless, he remained too distinctive to assimilate fully into the Protestant Irish elite around him.

| • | • | • |

Publication of Travels

Dean Mahomet's most lasting representation of himself as an Indian living in Cork remains his book Travels. In March 1793 (at age thirty-four), he took out a series of newspaper advertisements proposing to publish Travels by subscription, as was usual at the time.[4] He apparently supplemented his public advertisements with personal visits to many of the leading families in southern Ireland. Testifying to his acceptance as a literary figure, a total of 320 people entrusted him with a deposit of 2 shillings 6 pence each long in advance of the book's delivery.

Dean Mahomet clearly appealed to the social elite of Ireland, both men and women. Of the 238 males who subscribed, over 85 percent were gentlemen distinguished by a title, rank, or the epithet “esquire” (the rest bore the label “Mr.”). Included among the male subscribers were 17 members of the nobility, 10 military officers (up to Colonel), 17 clergymen (including 3 Bishops), and 3 medical men. The 82 women, over a quarter of the subscribers, included a Viscountess, 5 Ladies, and several Honorables (i.e., daughters of titled families). In addition, the Catholic Ursuline Convent purchased a set (which still remains in their library over two centuries later).[5] A number of Protestant Irishmen who had served in India and held estates in southern Ireland also appeared prominently among Dean Mahomet's patrons; he dedicated his book to one of them, Colonel William Annesley Bailie (1740/41–1821).[6] Having drawn great wealth from India, such officers continued their bonds to it, sponsoring Dean Mahomet and, sometimes, naming their estates after places in India: for example, William Popham's “Patna.”

Dean Mahomet chose to use for Travels the epistolary form then fashionable in Britain for fiction and travel literature. The epistolary style enabled an author to write more intimately and confidently—notionally to address a friend, rather than a faceless world of unknown readers. England had produced some eight hundred epistolary novels by 1790; this form was especially strong in the 1750–1800 period, when approximately every sixth work of fiction used it.[7] Like most contemporary authors of epistolary works, Dean Mahomet used the fiction of pretending to have written his letters contemporaneously with the events they described. Unlike many other authors of his day, however, he did not backdate these letters or devise a fictional dialogue with an imaginary correspondent.

Although Dean Mahomet began each of the thirty-eight letters in Travels with “Dear Sir,” he did not seem to have any single real or imagined person as his intended audience. Rather, internal evidence suggests he was addressing two types of readers. First, he was presenting India, and himself, to the elite society around him. Authorship proved him an educated man. Second, he intended, at least in part, Travels to be a functional guide for European travelers: young men or women considering a career in, or tour of, India. To this end, Dean Mahomet delineated Indian cities, industries, geography, flora, and fauna, he included a glossary of Persian and Indian terms and factual descriptions of major cities which he did not himself visit, and he designed the book in duodecimo format as two small volumes for easy portability.

When Dean Mahomet determined to write a travel narrative about India, he studied earlier travel narratives and copied parts of them, including Jemima Kindersley's Letters from the Island of Teneriffe…and the East Indies (1777) and, more extensively, John Henry Grose's Voyage to the East Indies (1766).[8] Kindersley and Grose present unsympathetic pictures of India and Indians. Nonetheless, Dean Mahomet found aspects of their work worthy of emulation, since he paraphrased or directly lifted material from them without attribution—a practice today termed plagiarism. To illustrate how Dean Mahomet used Grose's words without accepting his perspective or interpretation, I include a sample of both texts, underlining the words which he took from Grose. These passages describe eating betel leaf, something Dean Mahomet knew well without having to rely on Grose, and yet he clearly did so:

Where Grose used this passage to indicate his condemnation of such “vicious” habits indulged in by natives, Dean Mahomet used some of the same words to describe a healthful and luxurious practice, conducive to polite social intercourse. Overall, Dean Mahomet took 7 percent of the words in Travels from Grose, yet reconstructed them into his own voice.

Grose (vol. 1, p. 238) Dean Mahomet (XXVII) Another addition too they use of what they call Catchoo, being a blackish granulated perfumed composition, of the size of a small shot, which they carry in little boxes on purpose. They are pleasingly tasted, and are reckoned provocatives, when taken alone, which is not a small consideration with the Asiatics in general.

They pretend that this use of Betel sweetens the breath, fortifies the stomach, though the juice is rarely swallowed, and preserves the teeth, though it reddens them; but, I am apt to believe, that there is more of a vitious habit than any medicinal virtue in it, and that it is like tobacco, chiefly a matter of pleasure.Another addition they use, termed catchoo, is a blackish, granulated, perfumed substance; and a great provocative, when taken alone, which is not a small consideration with the Asiatics in general.

It is taken after meals, during a visit, and on the meeting and parting of friends or acquaintance; and most people here are confirmed in the opinion that it also strengthens the stomach, and preserves the teeth and gums. It is only used in smoking, with a mixture of tobacco and refined sugar, by the Nabobs and other great men, to whom this species of luxury is confined.

Although Dean Mahomet wrote Travels twenty-five years after the first events it narrated, and ten years after its last events, the specific details of names and places which he presented have proven quite precise when checked against English Company and other records. It is highly unlikely that Dean Mahomet himself took notes about all his adventures at the time, especially since they began when he was only eleven. He may have supplemented his recollection—and perhaps later notes—with the memories, diaries, or other papers of the Anglo-Irish officers then living in Cork who served with him in India. Nevertheless, the text stands clearly as his own. He orchestrated his various sources into his own narrative, as he understood and wished to present it to his patrons. The writing of such an elevated and refined work of literature, and its acceptance by elite society, buttressed his respectability, yet his self-presentation as Indian stressed his difference.

| • | • | • |

Cork Society

During the quarter century that Dean Mahomet lived in Cork, its citizens encountered a variety of images of India, quite apart from those he presented. Many had personal experience of Asia: as soldiers, officials, merchants, or travelers. Some had Indian mistresses and Anglo-Indian children. Cork newspapers periodically published lists of “Nabobs”: Britons who had returned from India with vast fortunes and exotic tastes.[9] Much of the literature and theater available in Cork held attitudes toward India or Islam that clashed with those espoused by Dean Mahomet.

One image of India prevalent in Cork remained that of the exotic. Traveling carnivals and circuses, books, plays, and newspaper articles all presented India and Muslims as alien curiosities.[10] For example, during Dean Mahomet's years in Cork, two plays proved particularly popular, staged repeatedly with a professional lead but with townspeople in the other roles. In 1788 and 1796, Cork produced the Reverend Mr. Miller's translation of Voltaire's Mahomet, The Impostor: A Tragedy which presented the Prophet Muhammad as a religious tyrant, using the faith of his followers to advance his corrupt personal agenda.[11] In 1791, 1804, and 1807, Cork performed The Sultan; or, a Peep into the Seraglio by Isaac Bickerstaff, which presented a plucky English slavewoman resisting the sexually and physically subordinated role specified for her by Islam, thereby winning over the Sultan, becoming Queen, and freeing the rest of the harem from bondage.[12] This theme of an English Christian woman converting a Muslim to her “higher” principles and then marrying him may have seemed to the people of Cork to be relevant to the marriage of ![]() Jane

Jane ![]() and Dean Mahomet.[13]

and Dean Mahomet.[13]

Some images, in contrast, emphasized the virtues of Indians. Cork newspapers included anecdotes illustrating the extreme pride and sense of honor of Indians: a high-caste Rajput servant who, hit unjustly by his master, committed suicide rather than accept the shame of either being struck or betraying his employer; grenadier sepoys who claimed the right to be executed first among “mutineers,” since grenadiers always had the honor of entering battle first.[14] Indeed, Dean Mahomet or one of his fellow veterans may have been the source of such newspaper stories designed to illustrate the exceptional virtue of Indians. Despite his representation of India and Indians in his own terms, the images that prevailed in Britain were those by European authors; the message of his book received little lasting attention from the British public.

Dean Mahomet and ![]() Jane

Jane ![]() seem to have lived fairly comfortably during their years in Cork. He may have brought some capital with him from India to Ireland. Godfrey Evan Baker may have helped establish Dean Mahomet in Cork, using money Baker had acquired in India, the Baker family's extensive properties, or money brought by Baker's wealthy marriage. The Baker clan's wide range of commercial enterprises would have had room for Dean Mahomet.

seem to have lived fairly comfortably during their years in Cork. He may have brought some capital with him from India to Ireland. Godfrey Evan Baker may have helped establish Dean Mahomet in Cork, using money Baker had acquired in India, the Baker family's extensive properties, or money brought by Baker's wealthy marriage. The Baker clan's wide range of commercial enterprises would have had room for Dean Mahomet. ![]() Jane

Jane ![]() Daly may also have brought property with her into their marriage. Most plausibly, Dean Mahomet worked as manager of the Baker household, probably not a servant in livery, but not an independent gentleman either. He later claimed much experience in marketing and running a kitchen.[15] As manager, he would have had some status in society but would also have been dependent on his patrons, the Bakers.

Daly may also have brought property with her into their marriage. Most plausibly, Dean Mahomet worked as manager of the Baker household, probably not a servant in livery, but not an independent gentleman either. He later claimed much experience in marketing and running a kitchen.[15] As manager, he would have had some status in society but would also have been dependent on his patrons, the Bakers.

In 1796, Captain William Massey Baker (well known by Dean Mahomet as Godfrey Evan Baker's younger brother who had served with them in the Bengal Army, once in the same battalion), returned to Cork on leave from the Company's army. William Massey Baker had done extremely well financially in India, as a Quartermaster and as an entrepreneur in a variety of private commercial activities, rather than depending on his modest army salary.[16] It is not clear if he brought his Indian mistress and their teenage Anglo-Indian daughter, Eleanor, with him to Cork.[17] Soon after his arrival in Cork, William Massey Baker purchased—for a reported £2,500—a large estate a few miles from Cork and built a fine Georgian house, with all the latest conveniences, on the site.[18] His mansion, Fortwilliam, still stands today (figure 4). When the Bakers shifted their household from downtown Cork to Fortwilliam, Dean Mahomet may have set up his own household on the estate.[19] There, in 1799, through a chain of remarkable coincidences, he met an Indian traveler who recorded their meeting.

Abu Talib Khan came from much the same Muslim service elite as Dean Mahomet, albeit from a slightly higher class. By 1799, however, Abu Talib found himself unemployed, and accepted an invitation from Captain David Richardson to visit London. Adverse winds kept Abu Talib's ship from reaching London directly, instead it sought shelter in Cork's harbor. Tired of the sea and shipboard fare, Abu Talib went ashore. He spontaneously decided to travel by land to Dublin, where he hoped to renew the acquaintance of his old patron, Marquis Cornwallis, formerly Governor-General of India (1786–93), currently Viceroy of Ireland (1798–1801), and later Governor-General of India again (1805). While dining in Cork, Abu Talib fortuitously encountered William Massey Baker, whom he and Captain Richardson had known in India. Baker impulsively invited Abu Talib to Fortwilliam, to show off its modern conveniences. While there, on December 7, 1799, Abu Talib met and chatted with Dean Mahomet. Abu Talib went on to a triumphant season in London's high society as a self-proclaimed “Persian Prince,” before returning to India. Thirteen years later, he wrote up a Persian-language account of his travels in Europe based on his notes of the trip. My translation of Abu Talib's account of Dean Mahomet suggests much about the latter's status:

Mention of a Muslim named Dean Mahomet: Another person in the house of the aforementioned Captain [William Massey Baker] is named Dean Mahomet. He is from Murshidabad. A brother of Captain [William Massey] Baker raised him from childhood as a member of the family. He brought him to Cork and sent him to a school where he learned to read and write English well. Dean Mahomet, after studying, ran off to another city with the daughter, known to be fair and beautiful, of a family of rank of Cork who was studying in the school. He then married her and returned to Cork. He now has several beautiful children with her. He has a separate house and wealth and he wrote a book containing some account of himself and some about the customs of India.[20]

Abu Talib's tone suggests that he considered himself socially superior to Dean Mahomet. Nevertheless, he states that Dean Mahomet had an independent income and living arrangements, clearly not the status of a servant. Further, Abu Talib considered Dean Mahomet still a Muslim, at least by culture. In Abu Talib's writings and self-reported behavior, he showed a particular interest in sexual relationships between Indian men and European women, so he appears to have probed the Bakers about Dean Mahomet's marriage and ![]() Jane's

Jane's ![]() status.

status.

Around 1807, Dean Mahomet decided to leave Ireland and move to London. The most probable cause of his departure was a change in his relationship to the Bakers. After a second stay in India (1800–1806), William Massey Baker returned again to Ireland. He soon made a distinguished marriage (February 19, 1807) to Mary Towgood Davies, the daughter of a prominent Protestant minister. We can speculate that her assumption of authority over the Fortwilliam household may have made Dean Mahomet's place there uncongenial, leading to his emigration. Whatever factors pushed him from Ireland or attracted him to London, he was at this time nearly fifty, unusually late in life in that era to undertake such a radical change.

In future, Dean Mahomet would expunge the quarter century he had lived in Ireland from his life story. He never later mentioned it in print or in reported conversation; indeed, he explicitly stated that he had come directly from India to England in 1784. Thus, he evidently never fully identified himself with society in Ireland and started a new life in the British capital.

| • | • | • |

Immigration to London

When Dean Mahomet and his family (including a ten-year-old son William, and perhaps other children born in Cork) moved to London, they entered a cosmopolitan city quickly becoming an imperial capital. London surpassed Calcutta and Cork in scale and power. England was growing wealthy from its industrializing economy and from exploitation of its colonies—particularly India and Ireland. Its capital became the dwelling place for a variety of peoples drawn by the imperial process, including Irish and Indian workers (among the proletariat) and British officials, officers, and merchants who had grown rich in the East (among the elite).

As England developed its national identity, it largely did so over and against the people of its colonies.[21] Irish people, attracted by the growing English economy, often found themselves in the bottom social and economic strata in London. Some two thousand Asian sailors made London's docklands their abode—either temporarily between voyages or terminally marooned there. Many hundreds of Indian servants or slaves had accompanied their masters or mistresses back to England, only to be abandoned with no means of return to India.[22] By law, the East India Company had the financial obligation to repatriate destitute Indians, but it was reluctant to discharge this responsibility.[23] Further, a number of Indian wives, mistresses, and children of British men lived on the margins of whatever social class that man occupied.[24] Finally, a few Indian noblemen visited England during Dean Mahomet's lifetime.[25] Thus, Dean Mahomet and his family, combining as they did both Indian and Irish identities, would have had a particularly difficult time establishing their place in London.

Significantly, Dean Mahomet and his family did not settle among either merchants doing business with India or Indian sailors. Rather, they lived near one of the most fashionable new centers of London high society: Portman Square. A few blocks north, in St. Marylebone Church, Dean Mahomet and ![]() Jane

Jane ![]() baptized Amelia (born August 8, 1808) and Henry Edwin (born December 15, 1810).[26]

baptized Amelia (born August 8, 1808) and Henry Edwin (born December 15, 1810).[26]

| • | • | • |

Dean Mahomet Works for a Nabob

After his arrival in London, Dean Mahomet began to work for a rich and controversial Scottish nobleman, the Honorable Basil Cochrane (1753–1826), sixth son of the eighth Earl of Dundonald. Cochrane had himself returned from India in 1805 as one of the wealthiest of the Nabobs and took the largest house in Portman Square.[27] Here, too, the Ottoman Turkish Ambassador established an imposing residence and a mosque.[28]

Much of Cochrane's vast fortune came from his contracts (which totaled £1,418,236) to provision the Royal Navy in India. Cochrane spent much of the rest of his life successfully disputing Navy charges of embezzlement against him. Meanwhile, Cochrane claimed to have developed a form of vapor cure while in India; he determined to improve the health of London's lower classes, and his own reputation, by establishing a vapor bath for their therapy at his plush home in Portman Square early in 1808. Dean Mahomet served in this vapor bath but Cochrane never acknowledged any Indian contribution to his invention.

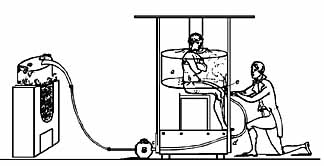

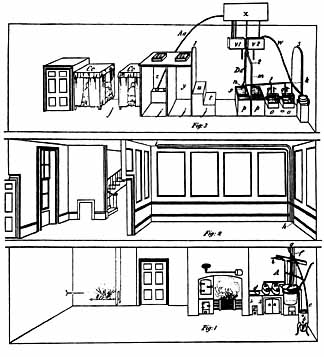

Although Cochrane claimed that he hit upon the original idea of a vapor bath while he was in India, he attributed his inspiration not to Indian tradition but rather to a British innovation which he encountered there: “an accident about this time threw in my way `Mudge's Inhaler,' and I made use of it…this naturally produced reflection on the superior advantages that might be obtained from vapour, upon an extensive scale, and with a more general application.”[29] In a work published later, Dean Mahomet's son, Horatio, acknowledged that the impetus for the establishment of the vapor bath in London had been Cochrane's, but then asserted that the “bath was fitted for” Cochrane by Dean Mahomet.[30] Diagrams supplied and captioned by Cochrane in 1809, showed the design he and his staff developed using flannel, whalebone, and metal pipe fittings and boilers (see figures 5 and 6).[31] Over the years, Cochrane's wealth and social standing enabled him to enlist large numbers of the most prominent members of the medical establishment to authenticate his innovation.[32] Cochrane publicized his contribution to public health repeatedly and widely. His most famous work, An Improvement on the Mode of Administering the Vapour Bath (1809), in many ways epitomized the self-promotional, quasi-medical literature of that era.

Despite Cochrane's assertions, the practice of vapor bathing in London was not original to him. Institutions using a range of forms of such baths had existed for centuries. Hamams, or Turkish steam baths, had been established in London as early as 1631 and have continued in various guises up to the present.[33]

The British conquest of India and Napoleon's invasion of Egypt (1798–1801) had brought ever larger numbers of Europeans into contact with—and power over—the “East.” In terms of medicine and health treatments, the perception of the Orient as exotic led to conflicting valuations. On one hand, Asia represented to many Europeans a largely unknown storehouse of wealth, including a wealth of medical knowledge, drugs, and treatments. On the other hand, the growing European conception of Asians as essentially different from themselves suggested that such medical knowledge and medicine might be specific to Asians and inapplicable or even dangerous for Europeans, particularly to Europeans who had not been subjected to the environment of Asia.[34] While Cochrane's innovation had no particular Indian associations, Dean Mahomet apparently added to Cochrane's bath a practice that he would make famous in England as “shampooing” (therapeutic massage).

Dean Mahomet later claimed to have been practicing shampooing in England from 1784.[35] Nevertheless, in Travels (Letter XXV) Dean Mahomet gave an unflattering account of this art, reproducing Latin citations giving derogatory descriptions by Seneca and Martial of such massage in imperial Rome as immoral and emasculating.[36] In the original context, Martial was castigating Zoilus, a sybarite who feasted surrounded by his catamite, concubine, slave boy, and female shampooer. Furthermore, in Travels, Dean Mahomet attributed this practice of shampooing (“champing”) to the Chinese. Yet by the time he made himself a practitioner of shampooing in England, he had clearly changed his attitude toward it.

Shampooing (champi) and the related art, malish, were widely practiced in India. As in Rome, however, many professional practitioners were servants or people of low status, both male and female. One of Dean Mahomet's contemporaries in Patna described a noble's attendants: “one of his…favourite women…presented herself at the foot of his bed…whose office was to chuppy [champi, shampoo] his limbs.…Within the seraglio, these…offices must be performed by women; and…they must be pretty, elegantly dressed, witty, and ready at repartees.”[37] European commentators about India also described practitioners of this art: “…of lulling to sleep in India…by the chuppy, a method of handling, from the feet upwards, all the members successively, opening the palm of the hand as if going to grip hard a handful of flesh, and yet grasping it so gently, as hardly to make any impression. The person that operates, is always a young one, and with long fingers, and a satined skin.”[38] Further, within a household, a wife or servant might regularly shampoo the elders of the family or a child to induce relaxation and sleep.

After Dean Mahomet began to shampoo in Cochrane's celebrated vapor bath, the idea of shampooing for health quickly entered the popular medical jargon of London; many commercial bathhouses included shampooing among their advertised therapies.[39] Dean Mahomet, however, gained little credit from Cochrane or the London public for his shampooing at this time. Instead, he began a new career: representing Indian culture and cuisine to the British elite.

| • | • | • |

The Hindostanee Coffee House (1809–12)

Late in 1809, Dean Mahomet opened a public eating house. He distinguished it from the thousands of other public houses then scattered across London by calling it the “Hindostanee Coffee House,” thus marketing his Indian identity.[40] In the location, furnishing, and advertising of this public eating house, he clearly sought to appeal and cater to the same type of men who had been his patrons in the past: Europeans who had worked or lived in India, men they called “Indian gentlemen.” He located his establishment near Portman Square: on the corner of George and Charles Streets, two short blocks directly behind Cochrane's mansion.[41] In selecting “coffee house” as the genre of his enterprise, he summoned up the Oriental origins which Londoners continued to attribute to coffee.[42] Like many other nominal coffeehouses of the day, however, he did not feature coffee at all. Rather, he created a restaurant, but one with a difference.

Unique among coffeehouses and other public houses then found in London, the Hindostanee Coffee House provided what Dean Mahomet and ![]() Jane

Jane ![]() intended their European patrons to recognize as exotic Indian cuisine and ambience. He prepared a range of meat and vegetable dishes with Indian spices and served with seasoned rice. He constructed bamboo-cane sofas and chairs on which his patrons would recline. He adorned the walls with a range of paintings including Indian landscapes, Indians engaged in various social activities, and sporting scenes set in India. One observer reported “Chinese pictures” as well, so he may have drawn upon Asia generally rather than India alone. In a separate en suite smoking room, he offered ornate hookas (water pipes), with especially prepared tobacco blended with Indian herbs.[43]

intended their European patrons to recognize as exotic Indian cuisine and ambience. He prepared a range of meat and vegetable dishes with Indian spices and served with seasoned rice. He constructed bamboo-cane sofas and chairs on which his patrons would recline. He adorned the walls with a range of paintings including Indian landscapes, Indians engaged in various social activities, and sporting scenes set in India. One observer reported “Chinese pictures” as well, so he may have drawn upon Asia generally rather than India alone. In a separate en suite smoking room, he offered ornate hookas (water pipes), with especially prepared tobacco blended with Indian herbs.[43]

Soon after he inaugurated his coffeehouse, he presented his creation to the British public through a newspaper advertisement:

This advertisement indicated his continuing public orientation toward Europeans who had traded or ruled in India, but also his effort to attract patronage from other segments of the British elite as well.Hindostanee Coffee-House, No. 34 George-street, Portman square—Mahomed, East-Indian, informs the Nobility and Gentry, he has fitted up the above house, neatly and elegantly, for the entertainment of Indian gentlemen, where they may enjoy the Hoakha, with real Chilm tobacco, and Indian dishes, in the highest perfection, and allowed by the greatest epicures to be unequalled to any curries ever made in England with choice wines, and every accommodation, and now looks up to them for their future patronage and support, and gratefully acknowledges himself indebted for their former favours, and trusts it will merit the highest satisfaction when made known to the public.[44]

The Hindostanee Coffee House received a favorable reception in some quarters. During their first year, he expanded his enterprise into the adjacent building.[45] One connoisseur of fine dining later listed Dean Mahomet among the “Artists who administer to the Wants and Enjoyment of the Table.”[46] To be profitable, however, public houses either had to generate a loyal and substantial clientele or to have a prime location, drawing many occasional visitors. Particularly successful London coffeehouses had already established themselves as hosts for specialized constituencies. Lloyds Coffee House over the previous half century had become central for ship insurers.[47] By the time Dean Mahomet began his enterprise, the Jerusalem Coffee House (in Cornhill, far closer to the City of London financial center) already held the patronage of European merchants and veterans of the East Indies.[48] The elite of the Portman Square neighborhood, including wealthy Nabobs, had their own private kitchens where their personal tastes would be satisfied; they could easily hire Indian servants, or Europeans with experience in India, if they sought to eat or smoke in an Indian style regularly.[49] Therefore, the relatively exclusive location of the Hindostanee Coffee House and its novel and specialized cuisine and ambience meant that its start-up costs exceeded Dean Mahomet's limited capital. After less than a year running the Hindostanee Coffee House on his own, he took in a partner, John Spencer, perhaps to infuse more cash into the business.[50] Spencer's partnership, however, proved either an inadequate recapitalization or simply a mistake, bringing with it even more financial difficulties. Less than a year after that (March 1812), Dean Mahomet (but not Spencer) had to petition for bankruptcy.[51] As a regretful aficionado of the former house suggested: “Mohammed's purse was not strong enough to stand the slow test of public encouragement.”[52] While the Hindostanee Coffee House apparently did eventually generate a loyal clientele and may have continued on the same site until as late as 1833, neither Dean Mahomet nor ![]() Jane

Jane ![]() held any further financial interest in it.[53]

held any further financial interest in it.[53]

Dean Mahomet's bankruptcy stripped him of his financial assets and kept him and his family enmeshed in complex legal processes until July 27, 1813—when his assets were publicly divided among his creditors in front of London's Guildhall. While this bankruptcy left the fifty-four-year-old Dean Mahomet free to begin yet another career, it must have been an extremely difficult period for him and his family. We can only imagine their frustration, particularly since they were recent immigrants trying to establish themselves in a distinctly English society which relegated most Indians and Irish to the lower classes. Not surprisingly, Dean Mahomet soon excised all reference to his life in London from his subsequent autobiographical writings.

Bankrupt, Dean Mahomet had to find a new way to support himself and his family. Late in 1812, he moved his family out of the Hindostanee Coffee House to a boardinghouse on Paddington Street, in a less attractive neighborhood a few blocks north. Their son William, in his midteens, may already have started working as a postman, an occupation he followed in London until his death.[54] The salary of a beginning postman, however, could hardly have supported the entire family. Further about this time, Dean Mahomet and ![]() Jane

Jane ![]() had another son, whom they named Deen, junior.

had another son, whom they named Deen, junior.

Dean Mahomet, lacking any other satisfactory employment, offered himself as an upper servant, hoping to revert to his earlier life running a wealthy household. His newspaper advertisement read: “MAHOMED, late of HINDOSTANEE Coffee House, WANTS a SITUATION, as BUTLER, in a Gentleman's Family, or as Valet to a Single Gentleman; he is perfectly acquainted with marketing, and is capable of conducting the business of a kitchen; has no objections to town or country.”[55] Virtually unique for such “Situations Wanted” advertisements in this period, he gave his name and his previous situation. Thus, he must have still identified himself with his failed business and have thought that he would be known to potential employers for his accomplished cuisine. Although he sought a position as the majordomo in a respectable household, based on his experience with the Bakers in India and Cork, he found employment in a vapor bathhouse, apparently based on his experience working for Cochrane.

| • | • | • |

The World of Brighton

Brighton, during the half century prior to the arrival of Dean Mahomet and his family, had been growing into a fashionable seaside spa. A series of popular medical texts drew public attention to sea bathing and the reputedly healthful marine environment of Brighton.[56] Sea bathing increased in popularity despite the fact that relatively few Englishmen or women actually knew how to swim. A growing number of English families could afford, and felt they deserved, a holiday by the seashore. Nevertheless, these same families were also developing a bourgeois mentality about revealing the body in public. To accommodate their interests and concerns, horse-drawn bathing machines, segregated by sex, sprang up along the Brighton shore to convey the bather into the water. Professional “dippers” stood at the foot of these machines to encourage the occasionally terrified bathers, via the dipper's arms, into the shallow seawater.

In addition to outdoor sea bathing, Brighton emerged as distinctive for its indoor activities as well. A series of medical promoters popularized their particular water treatments: indoor bathing in, or drinking, various types of waters as highly therapeutic for a broad range of maladies. In 1769, Dr. Awsiter established a hot and cold bathing institution at the foot of the Steine (the open area that ran down the middle of Brighton).[57] Other indoor bathing establishments followed, each with its own special method.[58] Thus, long before Dean Mahomet and ![]() Jane's

Jane's ![]() arrival in Brighton, a range of bathhouses flourished there.

arrival in Brighton, a range of bathhouses flourished there.

The flamboyant George IV—as Prince of Wales and then King—added a significant element of social prestige, and much income, to the expanding town. From his first visit in 1782 or 1783 onward, George's almost unbridled expenditures and increasing notoriety focused attention on the resort. For example, in 1784 he dramatically demonstrated his own prowess and the accessibility of Brighton by riding on horseback from Brighton to London and back in ten hours on one day.[59] Brighton offered George release from the social and moral restrictions of London and his father's court. Over the years, George remodeled a rented house into the striking Brighton Marine Pavilion.[60]

The Pavilion's major theme became eclectic Oriental exotica. A gift to George of Chinese-style wallpaper (c. 1802) led to extensive decoration and redecoration of the Pavilion in what George and his architects believed was “Eastern luxury.” While chinoiserie had been fashionable long before, a new amalgamation of putatively “Indian” themes made the Pavilion a striking expression of England's rapidly expanding eastern Empire, with India as its crown jewel (see figures 7 and 8). The Pavilion's final reconstruction into its current “Indian” form took place between 1815 and 1823, during Dean Mahomet's rise to fame in Brighton. He contributed a further fillip of the exotic to Brighton, which proved more receptive to his Indian offerings than London.

Figure 8. Rear of the Brighton Marine Pavilion (Horsfield, History [1835], vol. 1, p. 148).

[Full Size]

| • | • | • |

Dean Mahomet and  Jane

Jane  Move

Move

to Brighton

Burgeoning Brighton offered Dean Mahomet and ![]() Jane

Jane ![]() the opportunity to create new lives for themselves. By September 1814, they were established as bathhouse keepers at 11 Devonshire Place, on the eastern edge of town.[61] Here, Dean Mahomet advertised a range of exotic luxuries: “INDIAN TOOTH POWDER, which possesses extraordinary excellence. It is the first ever offered to the public in this country…also just introduced from India, the celebrated CULEFF [kalaf, Persian for red-black hair dye], for changing the Hair, of whatever colour it might be, to a beautiful glossy permanent BLACKNESS, which will ever remain unaffected by the attacks of time.”[62] Soon, however, they dropped the marketing of these substances to concentrate on a more promising line.

the opportunity to create new lives for themselves. By September 1814, they were established as bathhouse keepers at 11 Devonshire Place, on the eastern edge of town.[61] Here, Dean Mahomet advertised a range of exotic luxuries: “INDIAN TOOTH POWDER, which possesses extraordinary excellence. It is the first ever offered to the public in this country…also just introduced from India, the celebrated CULEFF [kalaf, Persian for red-black hair dye], for changing the Hair, of whatever colour it might be, to a beautiful glossy permanent BLACKNESS, which will ever remain unaffected by the attacks of time.”[62] Soon, however, they dropped the marketing of these substances to concentrate on a more promising line.

Dean Mahomet and ![]() Jane

Jane ![]() began to treat invalids using their own distinctive form of the therapeutic bath, Brighton's mainstay. They distinguished their form of the vapor bath from others by adding medical herbs and other substances to the vapor and calling it “the Indian Medicated Vapour Bath.” Dean Mahomet apparently simply modified Cochrane's apparatus (figures 5–6) with the addition of purportedly Indian elements. He used the same type of white flannel cloth and chair with footstool but, in place of Cochrane's whalebone framework, Dean Mahomet used wood, painted to resemble bamboo, suggesting the Orient. Into the vaporizing chamber, Dean Mahomet placed various “herbs and essential oils,…brought expressly from India, and…known only to myself.”[63]

began to treat invalids using their own distinctive form of the therapeutic bath, Brighton's mainstay. They distinguished their form of the vapor bath from others by adding medical herbs and other substances to the vapor and calling it “the Indian Medicated Vapour Bath.” Dean Mahomet apparently simply modified Cochrane's apparatus (figures 5–6) with the addition of purportedly Indian elements. He used the same type of white flannel cloth and chair with footstool but, in place of Cochrane's whalebone framework, Dean Mahomet used wood, painted to resemble bamboo, suggesting the Orient. Into the vaporizing chamber, Dean Mahomet placed various “herbs and essential oils,…brought expressly from India, and…known only to myself.”[63]

Dean Mahomet also featured “Shampooing with Indian oils.” His son—and a successor as shampooer—explained:

This description seems to indicate a conventional massage, although the exact nature of his proprietary “Indian oils” may never be known.[Shampooing]…consists of friction and extention of the ligaments, tendons, &c., of the body, the operation commencing by briskly administering gentle friction gradually increasing the pressure, along the whole course of the muscles; imperceptibly squeezing the flesh at the same moment: the operator then grasps the muscles with both hands whilst he kneads it with his fingers; this is succeeded by a light friction of the whole surface of the body…anointed with a medicated oil,…the muscles are then gently pounded with the thick muscle of the hand below the thumb.…[64]

For Dean Mahomet and ![]() Jane

Jane ![]() to succeed, they had to make clear both that their Indian methods were unique to their bathhouse and that those methods cured a broad range of complaints. To expand his clientele, Dean Mahomet took out a long series of ambitious newspaper advertisements, from early 1815 onward, to tout his treatments as a virtual panacea:

to succeed, they had to make clear both that their Indian methods were unique to their bathhouse and that those methods cured a broad range of complaints. To expand his clientele, Dean Mahomet took out a long series of ambitious newspaper advertisements, from early 1815 onward, to tout his treatments as a virtual panacea:

In format and broad claims, these early advertisements differed little from other aspiring practitioners of other cure-alls; in featuring “Indian” vapor and shampooing, however, they were distinctive, although later imitated.Mahomed's Steam and Vapour Sea Water Medicated baths…are far superior to the common Baths, as they promote copious perspiration, and never fail in giving relief when every thing else has been tried in vain, to cure many Diseases, particularly Rheumatic and Paralytic Affections of the extremities, stiff joints, old sprains, lameness, eruptions, and scurf on the skin, which it renders quite smooth; also diseases arising from the abuse of mercury, consumption, white swellings, aches and pains in the joints; in short, in all cases where the circulation is languid, or the nervous energy debilitated, as is well known to many professional gentlemen and others in this country.—Mr. M. has attended several of the Nobility with the happiest results, can give most satisfactory references.

N.B. Board and Lodgings in his House, if required.

→Mr. and Mrs. mahomed Possess the Art of shampooing.[65]

Their success and their family grew. Dean Mahomet claimed by 1815 to have treated “a thousand Cases.”[66] ![]() Jane

Jane ![]() gave birth to their daughter, Rosanna, early in 1815.[67] After only a year or so, they moved from the Devonshire Place baths to a more distinguished establishment.

gave birth to their daughter, Rosanna, early in 1815.[67] After only a year or so, they moved from the Devonshire Place baths to a more distinguished establishment.

| • | • | • |

The Battery House Baths (1815–20)

By December 1815, they had shifted to the Battery House, a more prominent location overlooking the sea, just down the Steine from the Royal Pavilion. The British Board of Ordinance still owned the Battery House, but vibrations from cannon fire and the erosion from the sea had combined to weaken this building's foundations and the cliff beneath.[68] As a result, the Board of Ordinance removed the cannon and rented out the building. There Dean Mahomet established his baths and lived with his growing family through 1819. This was their home when they baptized their sons Horatio (1816), Frederick (1818), and Arthur Ackber (1819) and buried their two-year-old daughter, Rosanna (1818).[69]

Increasingly, publicists who touted Brighton and its growing health care industry featured the Battery House Baths in their guidebooks. One stated that, with Dean Mahomet's treatment “the universal remedy…has at length been discovered.”[70] In addition to a growing body of loyal and distinguished clients, he also developed a personal history that presented him to his clients in a suitable manner.

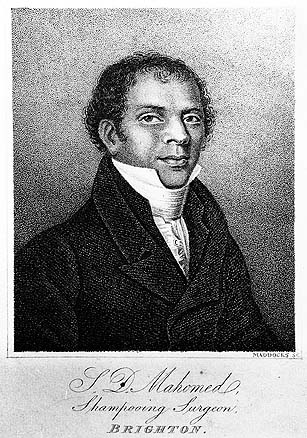

From about 1818, Dean Mahomet began to publicize the title he apparently invented for himself: “Shampooing Surgeon” (see figure 9). In 1820, Dean Mahomet extended his publicity campaign by publishing a book containing both descriptions of many of the cases he had treated and glowing testimonials from his grateful patients. Such tracts, while expensive to produce, were a frequent vehicle for bathhouse advertising.[71] He entitled the work Cases Cured by Sake [Shaikh] Deen Mahomed, Shampooing Surgeon, And Inventor of the Indian Medicated Vapour and Sea-Water Baths…(1820). He modestly attributed the impulse to publish this book to his distinguished patients: “By the pressing desires of many of the Nobility, and others of the first consideration, Sake Deen Mahomed has caused the few cases, herein presented to the public, to be printed.” In his brief opening “Address,” he implied that he had been doing shampooing since 1780. In later works, he would gradually make this claim more specific. By 1822, he had begun to assert that he had started shampooing in England in 1784 (see figure 10).[72]

Figure 9. S. D. Mahomed, Shampooing Surgeon, Brighton (Mahomed, Shampooing, frontispiece).

[Full Size]

During Dean Mahomet's years in the Battery House Baths, the entire medical bath industry continued to expand dramatically. Numbers of therapeutic baths sprang up across Britain, using a variety of types of vapor, chemicals, electricity, and other fluids as their healing medium. Like Dean Mahomet, the promoters of these other baths published numerous tracts, pamphlets, and books advertising their baths as universal remedies.[73] So, in order to prosper, he created a special niche for himself in the industry and in Brighton.

Since the Battery House building proved limiting, Dean Mahomet designed a magnificent, purpose-built bathhouse on the cliff top nearby. At the same time, the Brighton Town Council was developing the shorefront by building the Kings Road past that site. During the period when construction of this road disrupted traffic and commerce and/or while his new baths were under construction, Dean Mahomet shifted temporarily (1820–21) crosstown to a West Cliff location.[74]

The arrangements in his West Cliff establishment may not have been fully satisfactory. Two distressing incidents occurred there which could have ruined Dean Mahomet's budding career. John Claudius Loudon, a promising landscape gardener, took treatment at Mahomet's bath for a badly rheumatic right arm. The shampooers working under Dean Mahomet misjudged the brittleness of Loudon's humerus and snapped that bone close to the shoulder. This bone never healed properly; ultimately Loudon was compelled to have it amputated.[75] In the second incident, an elderly gentleman of means, Mr. Spode, died while undergoing a shower at Dean Mahomet's West Cliff baths. According to a newspaper report, Spode “ordered a shower bath, when he was ready, the water was, in the usual manner, discharged upon him, when, shocking to relate, he fell instantly dead. He death is supposed to have been produced by the shock being too severe for a frame already much debilitated, or from apoplexy. The coroner's verdict was—Died by the visitation of God.”[76] Despite these untoward incidents, the town of Brighton stood behind Dean Mahomet and his career continued to flourish. Kings Road officially opened on New Year's Day 1822 and Mahomet's new baths reopened for business about the same time.

| • | • | • |

Mahomed's Baths (1821–43)

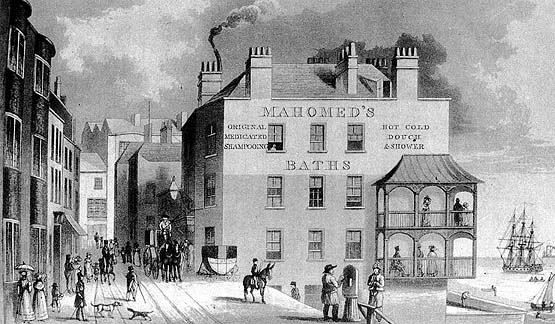

Mahomed's Baths stood as the most concrete expression of Dean Mahomet's professional success. He and a wealthy London backer, Thomas Brown, constructed the splendid baths at a particularly striking location, just down the Steine from the Brighton Pavilion, and perched on a prominent vantage point overhanging the shore on the new main seaside road (see figure 11).[77] This building first opened when Dean Mahomet had already turned sixty-two. Its location, imposing form, and elaborate internal decoration stood as testimony to the prominence he had reached in the community and in the bathhouse profession. A composite of several descriptions of his bathhouse from the time of its glory enable us to describe its design and ornamentation.[78] These descriptions convey the elements which Dean Mahomet evoked in his patients: Oriental and classical Grecian exotica, an almost religious faith in his method, his scientific medical professionalism, and the patronage of the elite. This combination made his bathhouse the epitome of fashion in Brighton for nearly two decades.

Visitors entered his bathhouse through a splendid vestibule off the fashionable Kings Road. Dean Mahomet covered the walls of this entrance room with a mural of “Moguls and Janissaries…represented in rich dresses, and the Muses…in plain Grecian attire.” Over the years, he further festooned the walls of this entry with relics, what a visitor called his “trophies in the shape of crutches, spine-stretchers, leg-irons, head-strainers, bump-dressers, and club-foot reformers…[bestowed by] former martyrs to rheumatism, sciatica, and lumbago. Mahomed's vigorous and scientific shampooing having restored them to health.” In this entryway as well, he kept his “visitor's books,” open for testimonials from his distinguished patients. He divided his patients by sex and class reserving one book, for example, for “Ladies of the Nobility.” He later mined these visitor's books, selecting particularly important patients or glowing tributes for his extensive and colorful publicity.

From this entry, ladies mounted the stairs to the floor above, while gentlemen proceeded directly ahead down a corridor. A naturalist described the walls of this corridor:

[a] profusion of trees laden with their fruits and rich foliage, meet the eye on every side, and description of the Duranta Plumina, the Chinese Limodoron, the large flowing sensitiloe plant or mimosa grandiflora, the rencalmina nutens or nodding grandiflora, the bouvardia versicolor, the bright rencalmis, is given with a correctness that is delightful. Birds of the gayest colours are represented also winging their rapid flight through sylvan groves, and Hebe is seen reclining on the ambent air, and strewing the earth with flowers, symbolical of the efficacy of the Medicated Baths, which are prepared in a peculiar manner from herbs, etc. the growth of India.

Awaiting their baths on separate floors, ladies and gentlemen amused themselves in reading rooms furnished with a variety of local and metropolitan newspapers and journals selected for the expected interests of their respective genders. These rooms faced south, overlooking the sea and, to the east and west, the Brighton seashore and open-air sea bathing machines. The walls of these rooms

In addition, ladies had a “boudoir” and gentlemen a “private parlour” in which to await their turn in the baths. Elevated balconies surrounded the building, including “an elegant sun screen” room.were beautifully painted in the most glowing colours, with Indian landscapes, from designs of Mr. Mahomed himself. On one side is seen a superb pagoda, surrounded by a variety of figures in the costume of the country, making their profound salams. On another is a gorgeous temple, beneath which is represented an enormous idol, the object of idolatrous worship. Here is the celebrated car of Jaggernaut, and here a messenger just dispatched on a distant journey, on his camel, and armed as they are seen in India. On one side is a Rajah's mausoleum, and on another a group of Brahmins, and on a third a group of native musicians sitting beneath the umbrageous trees of that prolific soil. Here is a lake whose liquid surface is lost beneath the rising bosom of those distant mountains whilst the swan, swelling with pride, gently breaks the monotonous stillness of the scene and the rich plumage of the Balearic and Numidian cranes.

Arranged symmetrically off each of the central corridors stood the bathing rooms themselves, four per floor. All of the bathing rooms “[are] fitted with a marble bath, and have the means of giving in the same room hot water, cold water, shower, and douche baths. Four of them are also fitted with the Indian vapour or shampooing baths, two of which are appropriated for ladies and two for gentlemen.” Above, five bedrooms awaited any patient who desired to remain for more extended treatment. Dean Mahomet located water closets discretely at various places within the building.

Unseen by the patients, but essential to the functioning of the Baths, were a basement with “a large coal and store cellars, breakfast room, a manservant's room, kitchens, scullery, and other offices. A spacious area, in which is the steam engine room, surrounds the west and south sides of the house, enclosed with an iron fence, which is a most important benefit to the comfort and security of the building.” This steam engine pumped the large volume of sea and fresh water used by the establishment. Figure 12 shows the structure and apparatus of such baths.[79]

Two men and three women lived as servants and bath attendants on the premises. No one on the staff, except Dean Mahomet, was Indian. Adjacent to the Baths stood a comfortable house where Dean Mahomet, ![]() Jane

Jane ![]() , and their growing family lived (figure 13 shows the only known portrait of Mrs.

, and their growing family lived (figure 13 shows the only known portrait of Mrs. ![]() Jane

Jane ![]() Mahomet).[80] To accompany this majestic new bathhouse, Dean Mahomet developed a new public persona for himself.

Mahomet).[80] To accompany this majestic new bathhouse, Dean Mahomet developed a new public persona for himself.

Figure 13. Mrs. Mahomed, Wife of Mr. Mahomed, Shampooing Surgeon, Brighton (courtesy of East Sussex County Library).

[Full Size]

| • | • | • |

Shifting Self-Presentations

Following the opening of his grand bathhouse, Dean Mahomet's fame and popularity grew dramatically. He enhanced this growth through frequent self-promotional publicity, projecting himself and his method as the latest in medical science and exotic fashion. In addition to his continuing newspaper advertisements, he expanded his book Cases Cured into a full medical casebook. Dean Mahomet followed the popular medical casebook genre by organizing his book around a quasi-scientific analysis of diseases, symptoms, methods, cures, and testimonials: Shampooing, or, Benefits Resulting From the use of The Indian Medicated Vapour Bath, As introduced into this country by S. D. Mahomed (A Native of India). In all, he published three editions of this book: 1822, 1826, 1838. Each edition expanded the previous one, adding another layer to the identity he had constructed in order to reflect the self-image that he wished to project at that time (see figure 9). This work received serious attention in at least one leading literary journal.[81]

In an age when each medical faculty (Physicians, Surgeons, and Apothecaries) was gradually organizing itself into a Royal College, with specified requirements for admission, Dean Mahomet came to feel the need for formal medical credentials.[82] In the first edition of Shampooing (1822), he claimed medical training in India, prior to his entry into the Company's army. To accommodate these years of medical training, he modified his life-story, increasing his putative age by a decade:

In the entrepreneurial environment of the early nineteenth century, a range of self-proclaimed experts made fortunes selling medicine and medical treatments to the public.[84] Dean Mahomet remained well within the bounds of medical and advertising ethics of the day.The humble author of these sheets, is a native of India; and was born in the year 1749, at Patna, the capital of Bihar, in Hindoostan.…I was educated to the profession of, and served in the Company's Service as, a Surgeon, which capacity I afterwards relinquished, and acted in a military character, exclusively for nearly fifteen years. In the year 1780, I was appointed to a company under General, then Major, Popham; and at the commencement of the year 1784, left the service and came to Europe, where I have resided ever since.[83]

Later family traditions among Dean Mahomet's descendants attributed to him professional training as “a medical student at the Hospital in Calcutta…[His commission as] Soubadar of the 27th Regiment…was offered by the Colonel…in grateful recognition of his skillful treatment of cholera among the soldiers.”[85] This family tradition is not supported either by East India Company records or Dean Mahomet's own Travels. A descendant rationalized the decadewide discrepancy in the dates Dean Mahomet gave for his birth in Travels and in Shampooing as due to the “difficulty” of conversion from the lunar Muslim calendar to the solar Christian calendar.[86] While Dean Mahomet may have given this implausible explanation to the curious and his descendants, the 1759 date of birth he stated in Travels accords perfectly with existing records and the chronology of the events of his life, while the 1749 date he claimed in Shampooing does not.

In the next edition of Shampooing (1826), Dean Mahomet further enhanced the amount of scientific testing that had gone into his “invention.” He explained how he developed his hypothesis about the properties of his vapor and shampooing, echoing the format of a scientific paper. He portrayed himself as an inventive, but disparaged, medical practitioner whose empirically derived method eventually triumphed over prejudice. This prejudice, however, rested not on racial grounds, but rather on his challenge as a newcomer to more established and conventional medical practitioners:

Thus, by this time, Dean Mahomet had located his medical methods within the European scientific discourse.It is not in the power of any individual to…attempt to establish a new opinion without the risk of incurring the ridicule, as well as censure, of some portion of mankind. So it was with me: in the face of indisputable evidence, I had to struggle with doubts and objections raised and circulated against my Bath.…Fortunately, however, I have lived to see my Bath survive the vituperations of the weak and the aspersions of the [in]credulous.…Upwards of a hundred medical gentlemen…of the first professional reputation…have since tried the experiment on themselves; most of them were invalids, but many were merely prompted by an honourable desire to ascertain truth.[87]

In addition to “modern” medicine, Dean Mahomet also drew upon the European classical tradition to support his treatment: “Homer mentions the use of private baths, which baths possessed medicinal properties.…[T]he Romans directed their attention in particular to the actual cure of disease by impregnated waters.”[88] This passage contrasts strikingly with the scathing classical references to shampooing by Martial and Seneca cited in Travels (Letter XXV).

Dean Mahomet further took authority for his method from ancient Hindu practice: “To the Hindoos, who are the cleanest and finest people in the East, we are principally indebted for the Medicated Bath.…”[89] Many among the British public never understood the distinction between Hindu and Muslim, or Dean Mahomet's relationship to either religious community, even after he had lived in Britain for over half a century.[90]

Nowhere, indeed, did Dean Mahomet specify his own training in shampooing or vapor bathing that would have prepared him for this career. He implied that his self-identification as a “native” of India had qualified him as a master of “Eastern” knowledge generally. Familiar as we are now with his earlier years, we can understand why, although he came to this career in his mid-fifties, he sought to indicate to his patients and potential patients a far longer commitment to the medical profession.

| • | • | • |

The Indian Method

Through his medical career, Dean Mahomet argued that, as an Indian, he was uniquely able to provide his patrons with access to Indian (and in a larger sense, “Oriental”) medical knowledge. He thus sought to preempt his rival European bathhouse keepers who sought themselves to represent the Orient. Nevertheless, as his fame grew, various competitors sought to appropriate the terms and methods “Indian Medicated Bath” and “Shampooing” for themselves.

One of his most competitive rivals, John Molineux, opened a bathhouse similar to Mahomed's Baths, but somewhat smaller and less elegant, two doors down on East Cliff in 1821.[91] In clear imitation of Dean Mahomet's shampooing and Indian medicated vapor baths, Molineux offered first “affriction” and then, in an effort to shift the origin of this method away from Dean Mahomet's area of expertise: “turkish medicated sea-water, vapour, and shampooing baths.”[92] Much to Dean Mahomet's disgust, many patrons and guidebooks confused the two baths, so similar were they in advertisements and location.[93]

In response to this situation, from June 1821 onward Dean Mahomet ran a series of front-page newspaper advertisements warning the public not to be fooled by

Molineux replied directly in his own advertisements, impugning Dean Mahomet's motives and medical training:…the many imitations of and the repeated attempts to rival his celebrated Indian Bath.…[T]he art of shampooing, as practiced in India, is exclusively confined to himself in Brighton.…[T]hough the outward appearance may be copied, the efficacy of it defies competition.

To avoid mistake the public are particularly requested to enquire for mahomed's baths, no. 39, east cliff.[94]

j. molineux thinks it his duty in answer to an advertizement that appeared in last week's Gazette [containing] unhandsome and unmanly allusions.…

J. M. does not, in the vulgar term, wish to gull the public by saying, that he was the first person that introduced Shampooing into this country, but, with the greatest confidence, he can say he understands it equal to any one who practices it, having, for the last eighteen years, been constantly employed therein, under the directions of the FIRST MEDICAL MEN IN THE WORLD, and thereby obtained a necessary knowledge of the human frame.…“Let man live without envy.”[95]

Even as these rivals battled over the provenance of shampooing (India or Turkey) and similarly the legitimacy of Dean Mahomet's claim as an Indian or Molineux's claim as a professional medical man, other bath proprietors also sought to capitalize on Dean Mahomet's reputation. In 1823, the oldest bathhouse in Brighton, the “Royal Original Hot, Cold and Improved Shower Baths” (founded in 1769), revised the treatment it featured to “Improved Indian Medicated Vapour and Shampooing.” The initial advertisement for this “new” method featured the term “improved” six times and “Indian” four times.[96] Eventually, however, these rivals gave up their direct imitation of Dean Mahomet's methods.

On his part, Dean Mahomet broadened his range of treatments. He provided courses of “vegetable pills,” “Paste or Wooptong baths,” “electuaries,” “dry cupping,” and “electrification”—some of which were not particularly Indian.[97] Thus, to attract broad-based attention and patronage, he did not restrict his publicity or methods to “Indian” traditions alone. Nevertheless, he rose out of the welter of claims and counterclaims among bathhouse keepers in a large measure because his undeniable identity as an Indian distinguished him from his rivals in the eyes of his patrons: the British public and royalty.

| • | • | • |

Shampooing Surgeon to Royalty

During Dean Mahomet's career, Brighton's most celebrated attractions, and sources of income, remained the courts of Kings George IV (r. 1820–30) and William IV (r. 1830–37). Dean Mahomet provided both Kings with shampooing and vapor bath treatments and received Warrants of Appointment as royal “Shampooing Surgeon” to their Majesties.[98] For attendance on such noble patients, he charged a royal rate of 1 guinea each for a shampoo and vapor bath. Further, his official court costume, modeled on Mughal imperial court dress, added another exotic touch to their royal assemblies and the Brighton horse races (see figure 14).

Figure 14. Sake Dean Mahomet in court robes (Erredge, History of Brighthelmston [1862], vol. 4).

[Full Size]

Over the years Dean Mahomet did much business with the royal household. He sold it baths and shampoos, an Indian Vapour Bath apparatus, bathing gowns of twilled calico and swanskin flannel, and other bathing gear.[99] In addition to Kings George and William, continental royalty, British aristocrats, and members of their entourages also took treatments from him.[100] A course of treatment from him became de rigueur for a fashionable visit to Brighton, even for Indian dignitaries.[101]

Even more valuable to Dean Mahomet than his fees from such royal patronage was the attention among the general public that it brought to him and his baths. His visits to the Royal Pavilion to supervise his vapor bath apparatus excited the fascinated gossip of Brighton society, in part because he received advanced word of the King's arrival in town.[102] Dean Mahomet capitalized on these royal connections by inserting the royal coat of arms in his newspaper advertisements (March 1822 onward). He also publicized his fervent expressions of loyalty to the royal family. He dedicated his book Shampooing to King George. He adopted a small, but for him unusual, public role in Brighton politics, placing himself among the inhabitants calling publicly for a Town Meeting to organize a reception for the newly crowned King William IV.[103] Further, he celebrated royal arrivals and anniversaries through elaborate gas-lamp signs and transparencies on the walls of his bathhouse. Such expressions were duly noted in the Brighton newspapers:

When the newly crowned Victoria (r. 1837–1901) first visited Brighton, Dean Mahomet displayed “a transparency of large dimensions, representing Her Majesty walking into Brighton, preceded by a number of damsels strewing flowers before her. … ”[105] His public expressions of loyalty to the royal family were not unusual among entrepreneurs in Brighton, where royal patronage bestowed the greatest cachet and attracted the attention of a less elevated but more broad-based market. Nevertheless, his arrays were repeatedly among the grandest.[Mahomed's baths displayed] portraits of the King and Queen [with the] motto “Welcome to Your People.” Under the portrait of the King was written “King William, Neptune's Favourite Son,” and under that of Her Majesty “Queen Adelaide, Patroness of Every Virtue”…[also] a transparency, representing Fame crowning William IV, Britannia supporting the portrait.[104]

By the late 1830s, however, his connection to the British royal family faded. King William's favor changed to other baths, making them more fashionable. Queen Victoria, despite Dean Mahomet's effusive expressions of loyalty, never graced his Baths or submitted herself to a bath or shampoo at his or ![]() Jane's

Jane's ![]() hands. Ultimately, she found Brighton uncongenial, closed the Pavilion, stripped its furnishings, and sold it the year Dean Mahomet died (1851). Nevertheless, Dean Mahomet's transient entry into the circle of attendants on the royal family did much to draw the attention of society at large to him and his mode of treatment.

hands. Ultimately, she found Brighton uncongenial, closed the Pavilion, stripped its furnishings, and sold it the year Dean Mahomet died (1851). Nevertheless, Dean Mahomet's transient entry into the circle of attendants on the royal family did much to draw the attention of society at large to him and his mode of treatment.

| • | • | • |

Social Position in Brighton

Dean Mahomet's rise and then decline in royal favor paralleled his reputation in Brighton society generally. His very identity as an Indian that made him stand out in society also marginalized him. Through the 1820s and early 1830s, he placed his name prominently before the public as a patron of worthy causes.[106] He further offered his medical treatment gratis to the deserving poor, as his advertisements and the press noted.[107] Although he had a reputation as a poor judge of horses, he contributed handsomely to the Brighton Race Fund through the 1820s, thus locating himself among the patrons of this sport of kings.[108] Such public acts of benevolence, however, were expensive; each one of his £5 donations represented the gross income from sixteen Indian vapor baths with shampooing.

Dean Mahomet and ![]() Jane's

Jane's ![]() lives had been uneven financially prior to arriving in Brighton, and this continued during their years there. On a good day, Mahomet's bathhouse could provide twelve Indian Medicated Vapor baths and thirty hot water baths. In theory, this worked out to be nearly £8 per day. Such an income, however, would rarely be sustained. In contrast, his fixed expenses remained high: rental to the building's owner, salaries to the attendants, expenses including coal and laundry, subscriptions to many newspapers, advertising costs, and taxes. Given the seasonal nature of resort life in Brighton, long periods of little or no business would have to be expected. Nevertheless, in flush times, there would be a handsome income, no doubt enhanced with tips. However, Dean Mahomet never controlled sufficient capital to free himself from financial dependence on his British backers.

lives had been uneven financially prior to arriving in Brighton, and this continued during their years there. On a good day, Mahomet's bathhouse could provide twelve Indian Medicated Vapor baths and thirty hot water baths. In theory, this worked out to be nearly £8 per day. Such an income, however, would rarely be sustained. In contrast, his fixed expenses remained high: rental to the building's owner, salaries to the attendants, expenses including coal and laundry, subscriptions to many newspapers, advertising costs, and taxes. Given the seasonal nature of resort life in Brighton, long periods of little or no business would have to be expected. Nevertheless, in flush times, there would be a handsome income, no doubt enhanced with tips. However, Dean Mahomet never controlled sufficient capital to free himself from financial dependence on his British backers.

Brighton's ambitious rebuilding of its seashore periodically disrupted his business. From the 1820s, the town built broad seawalls in front of the cliff and filled in the intervening space eventually to create a wide “Grand Junction Road” and esplanade. Beyond any financial losses incurred by this disruption in his usual custom, Dean Mahomet had to pay for part of the construction.[109] While the ultimate result was a more secure foundation for his bathhouse, during the construction, anyone seeking to visit his baths would have encountered noise and debris. Complaints by Dean Mahomet to the Town Commissioners about inadequate lighting and disruption met with little satisfaction.[110] Perhaps to compensate for obstructed access to his bathhouse, in 1838 he advertised a mobile bath service which carried attendants and a portable vapor bath apparatus to the patron's own rooms.[111] Further, all this construction isolated his bathhouse from the seashore. Instead of a prominent—if perhaps insecure—location on the cliff top, his bathhouse by about 1830 had become landlocked. Figure 15 shows that strollers now looked in at eye level to both the ground floor gentlemen's bathrooms and to the lowest level of the balcony, one of the building's most attractive architectural features.

Figure 15. Mahomed's Baths (computer-altered version of Berthou and Georges, Album de Brighton [Brighton: The Authors, 1838], pl. 5).

[Full Size]

Most British pen portraits of Dean Mahomet tended to paint him in sympathetic but eccentric terms, as an established Brighton “character,” identified with exotic India and Islam.[112] Some of his supporters identified him as in the forefront of modern medical innovation.[113] Among his detractors, the most consistent theme remained that his self-promotional advertising and his fashionable reputation were out of proportion to the medical benefits of his method.[114] Nevertheless, at the height of his career, Dean Mahomet had inserted “shampooing,” and, to an extent himself, into English popular culture as exotically attractive.

By the end of the 1830s, Dean Mahomet's leadership in Brighton's bathhouse industry had begun to falter. Already into his eighties, he may have found life as an inventive entrepreneur exhausting. Reviewers of bathhouses began to criticize his establishment as having become something of a “museum,” lacking “the air of freshness and sweet atmosphere” found in rival bathhouses. While his baths appeared passé, he personally remained “[o]ne of the greatest curiosities at Brighton.”[115]

Over the years, Dean Mahomet and ![]() Jane

Jane ![]() proved very interested in preparing three of their sons for careers as medical men. They apprenticed one son, Deen junior, to the King's own “Cupper”; “dry cupping” (applying vacuum cups to a patient's skin) and “wet cupping” (therapeutic bleeding of a patient) were highly fashionable at the time. Deen junior first worked at his father's bathhouse in Brighton. Dean Mahomet then established a branch bathhouse for Deen in a fashionable district of London, at 11 St. James Place, quite near both St. James Palace and numerous gentlemen's clubs.[116] Unfortunately, it seems Deen died sometime in 1836 and the bathhouse went to a competitor, George Fry.[117]

proved very interested in preparing three of their sons for careers as medical men. They apprenticed one son, Deen junior, to the King's own “Cupper”; “dry cupping” (applying vacuum cups to a patient's skin) and “wet cupping” (therapeutic bleeding of a patient) were highly fashionable at the time. Deen junior first worked at his father's bathhouse in Brighton. Dean Mahomet then established a branch bathhouse for Deen in a fashionable district of London, at 11 St. James Place, quite near both St. James Palace and numerous gentlemen's clubs.[116] Unfortunately, it seems Deen died sometime in 1836 and the bathhouse went to a competitor, George Fry.[117]

In response to Fry's unauthorized use of the name “Mahomed's Baths” for his establishment, Dean Mahomet opened another London bathhouse a few blocks away, at 7 Little Ryder Street, early in 1838. Dean Mahomet was nearly eighty years old and admitted a reluctance to take on this new operation. Nevertheless, he vowed to defeat Fry's rival business “carried on in [Dean Mahomet's] name, [but] with which he has not, nor ever had the slightest connection.”[118] Having beaten off his imitator, Dean Mahomet gradually withdrew from active involvement with the Ryder Street Baths, leaving them to his son, Horatio, to manage.[119]