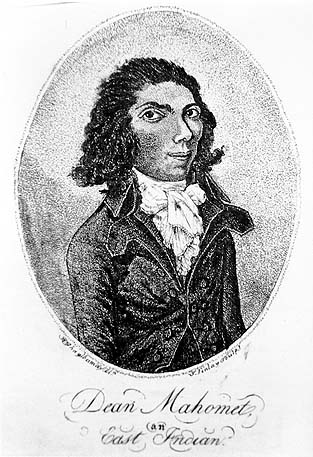

2. The Travels of Dean Mahomet,

A Native of Patna in Bengal,

Through Several Parts of India,

While in the Service of

The Honourable The East India Company

Written by Himself,

In a Series of Letters to a Friend

| • | • | • |

Dedication

To William A. Bailie, Esq., Colonel in the Service of

The Honourable the East India Company

Sir,

Your distinguished character both in public and private life, is a powerful incitement for soliciting your patronage; and your condescension in permitting me to honour my humble production with your name, claims my best acknowledgements.

Though praise is a kind of tribute due to shining merit and abilities; yet, Sir, even envy must confess, that your well-earned laurels, the meed of military virtues, obtained in the service of the Honourable the East India Company, have been too eminently conspicuous, to receive any additional lustre from the language of Encomium.

Your respectable name prefixed to these pages, cannot fail to shield them with the armour of security, as the judicious must be highly gratified with the peculiar propriety of inscribing them to a Gentleman so perfectly conversant with scenes, which I have attempted to describe.

Allow me to request, Sir, your indulgence for any inaccuracies of style, or other imperfections, that may arrest your judgment in glancing over this Work, as my situation in life, and want of the literary attainments, that refine and polish the European, preclude me from embellishing it, with that elegance of expression, and those fine touches of the imagination, which always animate the performance of cultivated genius.

However, Sir, I have endeavoured, at least, to please; and the sincerity of my intention, will, I trust, in some degree, make even an inadequate compensation for my deficiency in learning and refinement. I have the Honor to remain,

Sir, with the most profound veneration, your much obliged, and devoted, humble servant, Dean Mahomet, Cork, South-Mall, Jan. 15, 1794.

[List of subscribers omitted]

| • | • | • |

Letter I

Dear Sir,

Since my arrival in this country, I find you have been very anxious to be made acquainted with the early part of my Life, and the History of my Travels: I shall be happy to gratify you; and must ingenuously confess, when I first came to Ireland, I found the face of every thing about me so contrasted to those striking scenes in India, which we are wont to survey with a kind of sublime delight, that I felt some timid inclination, even in the consciousness of incapacity, to describe the manners of my countrymen, who, I am proud to think, have still more of the innocence of our ancestors, than some of the boasting philosophers of Europe.

Though I acknowledge myself incapable of doing justice to the merits of men, whose happy manners are worthy the imitation of civilized nations, yet, you will do me the justice to believe, that the gratification of your wishes, is the principal incitement that engages me to undertake a work of this nature: the earnest entreaties of some friends, and the liberal encouragement of others, to whom I express my acknowledgements, I allow, are secondary motives.

The people of India, in general, are peculiarly favoured by Providence in the possession of all that can cheer the mind and allure the eye, and tho' the situation of Eden is only traced in the Poet's creative fancy, the traveller beholds with admiration the face of this delightful country, on which he discovers tracts that resemble those so finely drawn by the animated pencil of Milton. You will here behold the generous soil crowned with various plenty; the garden beautifully diversified with the gayest flowers diffusing their fragrance on the bosom of the air; and the very bowels of the earth enriched with inestimable mines of gold and diamonds.

Possessed of all that is enviable in life, we are still more happy in the exercise of benevolence and good-will to each other, devoid of every species of fraud or low cunning. In our convivial enjoyments, we are never without our neighbours; as it is usual for an individual, when he gives an entertainment, to invite all those of his own profession to partake of it. That profligacy of manners too conspicuous in other parts of the world, meets here with public indignation, and our women, though not so accomplished as those of Europe, are still very engaging for many virtues that exalt the sex.

As I have now given you a sketch of the manners of my country; I shall proceed to give you some account of myself.

I was born in the year 1759, in Patna, a famous city on the north [south] side of the Ganges, about 400 miles from Calcutta, the capital of Bengal and seat of the English Government in that country. I was too young when my father died, to learn any great account of his family; all I have been able to know respecting him, is, that he was descended from the same race as the Nabobs of Moorshadabad [Murshidabad]. He was appointed Subadar in a battalion of Seapoys commanded by Captain Adams, a company of which under his command was quartered at a small district not many miles from Patna, called Tarchpoor [Tajpur], an inconsiderable fort, built on the side of a little river that takes its rise a few miles up the country. Here he was stationed in order to keep this fort.

In the year 1769, a great dearth overspread the country about Tarchpoor, where the Rajas' Boudmal [Budhmal], and his brother Corexin [Kora Singh] resided, which they took an advantage of by pretending it was impossible for them to remit the stipulated supplies to the Raja Sataproy [Shitab Rai], who finding himself disappointed in his expectations, sent some of his people to compel them to pay: but the others retired within their forts, determined on making an obstinate defence. My father having received orders to lead out his men to the scene of dispute, which lay about twelve miles from the fort he was quartered in, marched accordingly, and soon after his arrival at Taharah [Telarha], took the Raja Boudmal prisoner, and sent him under a strong guard to Patna, where he was obliged to account for his conduct. My father remained in the field, giving the enemy some striking proofs of the courage of their adversary; which drove them to such measures, that they strengthened their posts and redoubled their attacks with such ardour, that many of our men fell, and my lamented father among the rest; but not till he had entirely exhausted the forces of the Raja, who, at length, submitted. The soldiers, animated by his example, made Corexin a prisoner, and took possession of the fort.

Thus have I been deprived of a gallant father, whose firmness and resolution was manifested in his military conduct on several occasions.

My brother, then about sixteen years old, and the only child my mother had besides me, was present at the engagement, and having returned home, made an application to Capt. Adams who, in gratitude to the memory of my father, whose services he failed not to represent to the Governor, speedily promoted him to his post. My mother and I suffered exceedingly by his sudden yet honourable fate in the field: for my Brother was then too young and thoughtless, to pay any great attention to our situation.

I was about eleven years old when deprived of my father, and though children are seldom possessed of much sensibility or reflection at such immature years, yet I recollect well no incident of my life ever made so deep an impression on my mind. Nothing could wear from my memory the remembrance of his tender regard. As he was a Mahometan, he was interred with all the pomp and ceremony usual on the occasion. I remained with my mother some time after, and acquired a little education at a school in Patna.

| • | • | • |

Letter II

Dear Sir,

In a few months after my father's fate, my mother and I went to Patna to reside: she lived pretty comfortable on some of the property she was entitled to in right of her husband: the rest of his substance, with his commission, came into the hands of my brother: our support was made better by the liberality of the Begum and Nabob, to whom my Father was related: the Begum was remarkably affectionate and attentive to us.

The Raja Sataproy had a very magnificent palace in the centre of the city of Patna, where he was accustomed to entertain many of the most distinguished European Gentlemen, with brilliant balls and costly suppers. My mother's house was not far from the Raja's palace; and the number of Officers passing by our door in their way thither, attracted my notice, and excited the ambition I already had of entering on a military life. With this notion, I was always on the watch, and impatiently waited for the moment of their passing by our door; when, one evening in particular, as they went along, I seized the happy opportunity, and followed them directly to the palace, at the outward gates of which there are sentinels placed, to keep off the people and clear the passage for the Gentlemen; I however got admittance, on account of the respect the guards paid my father's family. The Gentlemen go to the palace between seven and eight o'clock in the evening, take tea and coffee, and frequently amuse themselves by forming a party to dance; when they find themselves warm, they retire to the palace yard, where there are marquees pitched for their reception; here they seat themselves in a circular form, under a semiana, a sort of canopy made of various coloured double muslin, supported by eight poles, and on the ground is spread a beautiful carpet; the Raja sits in the centre; the European Gentlemen on each side; and the Music in the front. The Raja, on this occasion, is attended by his Aid-du-Camps and Servants of rank. Dancing girls are now introduced, affording, at one time, extreme delight, by singing in concert with the Music, the softest and most lively airs; at another time, displaying such loose and fascinating attitudes in their various dances, as would warm the bosom of an Anchoret: while the servants of the Raja are employed in letting off the fire-works, displaying, in the most astonishing variety, the forms of birds, beasts, and other animals, and far surpassing any thing of the kind I ever beheld in Europe: and to give additional brilliancy to the splendor of the scene, lighted branches blaze around, and exhibit one general illumination. Extremely pleased with such various entertainment, the Gentlemen sit down to an elegant supper, prepared with the utmost skill, by an Officer of the Raja, whose sole employ is to provide the most delicious viands on such an occasion: ice-cream, fowl of all kinds, and the finest fruit in the world, compose but a part of the repast to which the guests are invited. The Raja was very happy with his convivial friends; and though his religion forbids him to touch many things handled by persons of a different profession, yet he accepted a little fruit from them; supper was over about twelve o'clock, and the company retired, the Raja to his palace, and the Officers to their quarters.

I was highly pleased with the appearance of the military Gentlemen, among whom I first beheld Mr. Baker, who particularly drew my attention: I followed him without any restraint through every part of the palace and tents, and remained a spectator of the entire scene of pleasure, till the company broke up; and then returned home to my mother, who felt some anxiety in my absence. When I described the gaiety and splendor I beheld at the entertainment, she seemed very much dissatisfied, and expressed, from maternal tenderness, her apprehensions of losing me.

Nothing could exceed my ambition of leading a soldier's life: the notion of carrying arms, and living in a camp, could not be easily removed: my fond mother's entreaties were of no avail: I grew anxious for the moment that would bring the military Officers by our door. Whenever I perceived their route, I instantly followed them; sometimes to the Raja's palace, where I had free access; and sometimes to a fine tennis court, generally frequented by them in the evenings, which was built by Col. Champion, at the back of his house, in a large open square, called Mersevillekeebaug [Mir Afzal ka Bagh]: here, among other Gentlemen, I one day, discovered Mr. Baker, and often passed by him, in order to attract his attention: he, at last, took particular notice of me, observing that I surveyed him with a kind of secret satisfaction; and in a very friendly manner, asked me how I would like living with the Europeans: this unexpected encouragement, as it flattered my hopes beyond expression, occasioned a very sudden reply: I therefore told him with eager joy, how happy he could make me, by taking me with him. He seemed very much pleased with me, and assuring me of his future kindness, hoped I would merit it. Major Herd [Heard] was in company with him at the same time: and both these Gentlemen appeared with distinguished eclat in the first assemblies in India. I was decently clad in the dress worn by children of my age: and though my mother was materially affected in her circumstances, by the precipitate death of my father, she had still the means left of living in a comfortable manner, and providing both for her own wants and mine.

| • | • | • |

Letter III

Dear Sir,

My mother observing some alteration in my conduct, since I first saw Mr. Baker, naturally supposed that I was meditating a separation from her. She knew I spoke to him; and apprehensive that I would go with him, she did everything in her power to frustrate my intentions. Notwithstanding all her vigilance, I found means to join my new master, with whom I went early the next morning to Bankeepore [Bankipur], leaving my mother to lament my departure. As Bankeepore is but a few miles from Patna, we shortly arrived there, that morning. It is a wide plain, near the banks of the Ganges, on which we encamped in the year of 1769. It commands a most beautiful prospect of the surrounding country. Our camp consisted of four regiments of Seapoys, one of Europeans, two companies of Cavalry, and one of European Artillery: the Commander in Chief was Col. Leslie; and next to him in military rank was Major Morrison; Capt. Lundick [Landeg] had the direction of the Cavalry; and Capt. Duff of the Artillery. The camp extended in two direct lines, at Patna side, along the river, on the banks of which, for the convenience of water, were built the Europeans' bangaloes: at one extremity of the line, was Col. Leslie's; at the other, Major Morrison's. The second line was drawn in a parallel direction with the first, at a about a quarter of a mile from the river; the front was the residence of the Officers; the rere a barrack for the soldiers; and the intermediate space was left open for the purpose of exercising the men, a duty which was, every day, performed with punctuality. Near a mile farther off, was the Seapoys' chaumnies; and a short space from them, the horse barrack. Thus was the situation of the camp at Bankeepore.

The Officers' bangaloes were constructed on a plan peculiar to the taste of the natives. They were quite square; the sides were made of mats, and the roof, which was supported by pillars, thatched with bamboes and straw, much after the manner of the farmer's houses in this country [Ireland]: their entrance was wide, and opened to a spacious hall that contained on each wing, the servants' apartments, inside which, were the gentlemen's dining-rooms and bed-chambers, with large frames in the partitions, and purdoes, that answered the same end as our doors and windows fastened to those frames.

Purdoes' are a contrivance made of coarse muslin, ornamented with fancy stripes and variegated colours, and so well quilted that they render the coolest situations agreeably warm: they are let up and down occasionally, to invite the refreshing breeze, or repel the sickly sunbeam. Inside is a kind of screen called cheeque, made of bamboes as small as wire, and interwoven in a curious manner, with various coloured thread, that keeps them together: it is let up and down like the purdoe, when occasion requires, and, admirable to conceive! precludes the prying eye outside from piercing through it, though it kindly permits the happy person within to gaze on every passing object.

The Colonel and Major had larger and more commodious bangaloes, than the other Officers, with adjacent out-houses, and stables. On the left angle, fronting the road, was the Colonel's guard-house, and stood diametrically opposite to his bangaloe; between which and those of the Officers, is situate an ever-verdant grove inclosed with a brick wall: overshadowed by the spreading trees inside, a few grand edifices built by the Nabobs, made a fine appearance; among which was the Bank of Messieurs Herbert and Halambury [Hollingberry], the dwelling of Mr. Barry [Berrie], Contract Agent, and a powder magazine.

The barrack of the European soldiers, was a range of apartments, whose partitions were made of mats and bamboes, and roofs thatched with straw. The chaumnies of the Seapoys were on the same plan; and such of them as had families, built dwellings near the chaumnies.

There are but few public buildings at Bankeepore: the only remarkable one that appeared in its environs, was the house of Mr. Goolden [Golding], who lived about a mile from the camp: it was a fine spacious building, finished in the English style; and as it stood on a rising ground, it seemed to rear its dome in stately pride, over the aromatic plains and spicy groves that adorned the landscape below, commanding an extensive prospect of all the fertile vales along the winding Ganges flowery banks. The happy possessor of this finely situated mansion, was in high esteem among the Officers, for his politeness and hospitality.

At some distance from Mr. Goolden's, lived Mr. Rumble [Rumbold], a Gentleman who received the Contracts of the Company, for the supply of Boats and other small craft. Mr. Baker had the utmost esteem for this Gentleman, for his many good qualities, and frequently visited him. For the honour of my country, I cannot help observing here, that no people on earth can be more attentive or respectful to the European Ladies residing among them, than the natives of all descriptions in India.

In gratitude to the revered memory of the best of characters, I am obliged to acknowledge that I never found myself so happy as with Mr. Baker: insensible of the authority of a superior, I experience the indulgence of a friend; and the want of a tender parent was entirely forgotten in the humanity and affection of a benevolent stranger.

I remember to have seen numbers perish by famine this year: the excessive heat of the climate, and want of rain, dried up the land; and all the fruits of the earth decayed without moisture.

Numbers of people have dropped down in the streets and highways: none fared so well as those whose plantations were watered by wells. The proprietors, some of whom were Nabobs, and other European Officers, distributed as much rice and other food as they could possibly spare, among the crowds that thronged into their court-yards and houses: but the poor creatures, quite spent and unable to bear it, fell down and expired in their presence: some endeavoured to crawl out and perished in the open air. Little did the treasures of their country avail them on this occasion: a small portion of rice, timely administered to their wants, would have been of more real importance than their mines of gold and diamonds.

| • | • | • |

Letter IV

Dear Sir,

When six or seven months had elapsed from the time I was first received by Mr. Baker, my mother unhappy at the idea of parting with me, and resigning her child to the care of a European, came to him, requesting, in the language of supplication, that I might be given up to her: moved by her entreaties, he had me brought before her, at the same time observing, that it was so remote from his intentions to keep me from her, he was perfectly reconciled to part with me, were it my inclination. I was extremely affected at her presence; yet my deep sense of gratitude to a sincere friend conquered my duty to an affectionate parent, and made me determine in favour of the former: I would not go, I told her—I would stay in the camp; her disappointment smote my soul—she stood silent—yet I could perceive some tears succeed each other, stealing down her cheeks—my heart was wrung—at length, seeing my resolution fixed as fate, she dragged herself away, and returned home in a state of mind beyond my power to describe. Mr. Baker was much affected, and with his brother Officers, endeavoured to find amusement for me. I was taken out, every morning, to see the different military evolutions of the men in the field, and on such occasions, I was clad myself in suitable regimentals. Capt. Gravely in particular, was very fond of me, and never passed by without calling to know how I was. This kind attention gradually dispelled the gloom which, in some pensive moments, hung over my mind since the last tender interview. My poor mother under all the affliction of parental anxiety, and trembling hope for my return, sent my brother as an advocate for her to Mr. Baker, to whom he offered four hundred rupees, conceiving it would be a means of inducing him to send me back: but Mr. Baker had a soul superior to such sordid purposes, and far from accepting them, he gave me such a sum to bestow my mother. Having given his people the necessary directions to conduct me to her, he provided for me his own palankeen, on which I was borne by his domestics.

When I arrived at my mother's, I offered her the four hundred rupees given me by my disinterested friend to present to her; but could not, with all my persuasion, prevail on her to receive them, until I told her she should never see me again, if she refused this generous donation. Thus, by working on her fears, I, at length, gained my point, and assured her that I would embrace every opportunity of coming to see her: after taking my leave of her, I returned on the palankeen to the camp.

We lay in Bankeepore about six months, when we received orders from Col. Leslie to march to Denapore [Denapur], where we arrived in the year of 1770, and found the remaining companies of the Europeans and Seapoys, that were quartered there for some time before. Our camp here, consisted of eight regiments; two of Europeans, and six of Seapoys. Denapore is eight miles from Bankeepore, and has nothing to recommend it but a small mud fort, on which some cannon are planted, fronting the water. Inside the fort is a very fine barrack, perhaps the first in India; and when it was ready to receive the number of men destined to serve in that quarter, we marched into it. `Tis a fine square building, made entirely of brick, on the margin of the Ganges, and covers both sides of the road; on the east side, opposite the river, were the Captain's apartments, consisting of two bed chambers and a dining room, with convenient out-offices, stables, and kitchen, at the back of the barrack: a little distance farther out on the line, was the General's residence, an elegant and stately building, commanding a full view of the country many miles round. It was finished in the greatest style, and furnished in a superb manner: the ascent to it was by several flights of marble steps, and the servants about it were very numerous. In the north angle, on the same line, was the hospital, at a convenient distance from the barrack. In the other angles were planted some cannon, which were regularly discharged every morning and evening, as the flag was hoist up or pulled down. At one end of the fourth side, was the Artillery barrack; at the other, their stores: on the west, lay the companies of the brigade; on the north, the Doctors and inferior Officers had their apartments. About a mile thence, were the chaumnies of the Seapoys.

No situation in the world could be more delightful than that of the General's mansion; at the front and back of which, were gravel walks, where the soldiers and servants, at leisure hours, were accustomed to take recreation. A mud battery is drawn round the whole; and from north to south is a public road for travellers, which is intersected by another from east to west. Country seats and villas were dispersed through the neighbouring country, which was highly cultivated with fertile plantations and beautiful gardens. At one end of the avenue leading to the barrack, stood the markets or bazars of the Europeans; at the other, near their chaumnies, were those of the natives. Colonels Morgan, Goddard, and Tottingham, commanded here this year; and the army was mostly employed in going through the different manoeuvres in the field, as there happened no disturbances of any consequence in the country, that interfered with this duty. I called now and then to see my mother, who, at last, became more reconciled to my absence; and received some visits from my brother while I was in camp.

| • | • | • |

Letter V

Dear Sir,

I felt great satisfaction in having procured the esteem of my friend, and the other Officers, and acquired the military exercise, to which I was very attentive. We lay about eight months in Denapore, when Col. Morgan having received intelligence of the depredations committed by some of the Morattoes [Marathas], gave orders to the army to make the necessary preparations for marching to Chrimnasa [Karamnasa], at a moment's warning. The baggage was immediately drawn out, and the cattle tackled with the utmost expedition. The Quarter Masters provided every necessary accommodation for the march: some of the stores they sent before them by water; the rest was drawn in hackeries and wagons, by bullocks. Mr. Baker, who was also Quarter Master, and his brother Officers in the same line, had each a company of Seapoys, as a piquet guard along the road, and about seven hundred attendants, who were occasionally employed, as the army moved their camp, in pitching and striking the tents, composed of the lowest order of the people residing in the country, and forming many distinct tribes, according to their various occupations. We had a certain number of these men appointed to attend the garrison, which was usually augmented on a march, and distinguished under the various appellations of Lascars, Cooleys, Besties, and Charwalleys. They set out with us, a day before the main body of the army, accompanied by several classes of tradesmen, such as shoe-makers, carpenters, smiths, sail-makers, and others capable of supplying the camp; and were ranged into four departments, in order to perform the laborious business of the expedition without confusion. To each department was assigned its respective duty: the employment of the Lascars, who wore mostly a blue jacket, turban, sash, and trousers, was to pitch and strike the tents and marquees; load and unload the elephants, camels, bullocks, waggons &c. The Cooleys were divided into two distinct bodies for different purposes; to carry burthens, and to open and clear the roads through the country, for the free passage of the army and baggage: The Besties were appointed to supply the men and cattle with water: and the Charwalleys, who are the meanest class of all, were employed to clean the apartments, and do other servile offices. Thus equipped, we marched in regular order from Denapore, early in the morning, in the month of February and the year of 1771. We enjoyed a pleasant cool breeze the entire day; while the trees, ever blooming and overshadowing the road, afforded a friendly shelter and an agreeable view along the country. The road was broad and smooth, and in places contiguous to it, we found several refreshing wells to allay the thirst of the weary traveller. In a few hours we reached Fulwherea [Phulwari], a spacious plain adapted for our purpose, where the Quarter Masters ordered out the Lascars to pitch the tents and marquees on the lines formed by them. Our camp, which made a grand military appearance, extended two miles in length: it was ranged into nine separate divisions, composed of two battalions of Europeans, six regiments of Seapoys, and one company of European Artillery. On the front line, the standards of the different regiments were flying: it consisted of a number of small tents called beltons [bell-tents], where they kept their fire arms: the central ones belonged to the Europeans; near them, were those of the Artillery; and on each wing, the Seapoys. The several corps were encamped behind their respective beltons, close to which, were first the tents of the privates; about twenty feet from their situation, were the larger and more commodious ones of the Ensigns and Lieutenants; next to them the Captains' marquees; a little farther back, the Major's; at some distance behind the two battalions, and in a middle direction between them, was the Colonel's, which lay diametrically opposite the main guard, situate outside the front line in the centre: a small space from the Colonels' marquees was the stop line, where the Quarter Masters, Adjutants, Doctors and Surgeons, were lodged: and between the stop line and bazars, was the line for the cattle. Every company of European privates occupied six tents and one belton: an Ensign, Lieutenant, and Captain, each a tent: such Officers as had jenanas or wives, erected tomboos, a kind of Indian marquees, for them, at their own expence. A Major had two marquees, one store, one guard tent, and one belton; a Colonel, three marquees, two store, two guard tents, and one belton; the Quarter Masters, Adjutants, Doctors and Surgeons, had each one marquee. On account of their peculiar duty in furnishing the camp, the Quarter Masters had, besides their own, other tents for their Serjeants, Artificers, and stores. The Seapoys lay behind their beltons, in the same position as the Europeans, and their Officers, according to rank, were accommodated much in the same manner. The hospital was in a pleasant grove not remote from the camp, about half a mile from which were the magazine and other stores for ammunition and military accoutrements; and on an eminence, at some distance, over the wide plain, where we encamped, arose in military grandeur, the superb marquees of the general Officers. In the rere of the entire scene, were the bazars or markets, belonging to the different regiments, on a direct line with each, and distinguished from one another, by various flags and streamers that wantoned in the breeze. Our camp, notwithstanding its extent, number of men, equipage, and arrangements, was completely formed in the course of the evening we arrived at Fulwherea, which is about twelve miles from Denapore.

| • | • | • |

Letter VI

Dear Sir,

We had scarcely been one night at Fulwherea, when some straggling villagers of the neighbouring country, stole unperceived into our camp, and plundered our tents and marquees, which they stripped of every thing valuable belonging to Officers and privates. It happened, at the same time, that they entered a store tent, next to Mr. Baker's marquee, where I lay on a palankeen, a kind of travelling canopy-bed, resembling a camp bed, the upper part was arched over with curved bamboo, and embellished with rich furniture, the top was hung with beautiful tassels and adorned with gay trappings; and the sides, head, and foot were decorated with valuable silver ornaments. In short, it was elegantly finished, and worth, at least six hundred rupees; for which reason, such vehicles are seldom kept but by people of condition. Every palankeen is attended by eight servants, four of whom, alternately, carry it, much in the same manner as our sedan chairs are carried in this country [Ireland]. But to return—the villagers having entered the store-tent above mentioned, bore me suddenly away to a field about half a mile from the camp, on the conveyance I have just described to you, which they soon disrobed of its decorations, and rifled me of what money I had in my pocket, and every garment on my body, except a thin pair of trousers. So cruel were the merciless savages, that some were forming the barbarous resolutions of taking away my life, lest my escape would lead to a discovery of them; while others less inhuman, opposed the measure, by observing I was too young to injure them, and prevailed on their companions to let me go. I reached the camp with winged feet, and went directly to Mr. Baker, who was much alarmed when he heard of my dangerous situation, but more astonished at my arrival; and when I related by what means my life was spared, and liberty obtained, he admired such humanity in a savage breast.

A few of those ravagers, who loitered behind the rest, were first detected by the guard, pursued, and taken: the track of others was, by this clew, discovered; many of whom were apprehended, and received the punishment due to their crimes, for such wanton depredations. They were flogged through the camp, and their ears and noses cut off, as a shameful example to their lawless confederates. Their rapacity occasioned us to delay longer at Fulwherea, than we intended. We had scarcely suppressed those licentious barbarians, when our quiet was again disturbed by the nocturnal invasion of the jackals that infest this country, ferocious animals not unlike the European fox; they flocked into our camp in the silent midnight hour, carried off a great part of the poultry, and such young children as they could come at. It was in vain to pursue them; we were obliged to endure our losses with patience.

Having dispatched the proper people to supply the markets, we left Fulwherea early on the eighth morning after our arrival, and proceeded in our march towards Chrimnasa, which lay about ninety miles farther off. We reached Turwherea, on the first day's march, where we had a river to cross, which retarded us three days, on account of our numbers. As the weather was very warm, we advanced slowly, and found it exceedingly pleasant to travel along the roads shaded with the spreading branches of fruit-bearing trees, bending under their luscious burthens of bannas, mangoes, and tamarinds. Beneath the trees, were many cool springs and wells of the finest water in the universe, with which the whole country of Indostan abounds: a striking instance of the wisdom of Providence, that tempers “the bleak wind to the shorn lamb,” and the scorching heat of the torrid zone to the way-worn traveller.

The former natives of this part of the world, whose purity of manners is still perpetuated by several tribes of their posterity, having foreseen the absolute necessity of such refreshment, and that in the region they inhabited, none could be more seasonable than founts of water for the use of succeeding generations, contrived those inexhaustible sources of relief in situations most frequented; and to prevent any thoughtless vagrant from polluting them, took care to inspire the people with a sacred piety in favour of their wells, and a religious dread of disturbing them. For this reason, they remain pure and undefiled, through every age, and are held in the most profound veneration. Wherever we found them, on the march, our Besties stopped to afford the men some time to recruit themselves, and take in a fresh supply of water, which was carried by bullocks, in leathern hanpacallies or bags made of dried hides, some of which were borne by the Besties on their shoulders.

| • | • | • |

Letter VII

Dear Sir,

In about fifteen days after we left Fulwherea, we arrived at Chrimnasa, and encamped on the banks of the Ganges: the Morattoes fled on our arrival. Chrimnasa is an open plain, near which is a small river that flows into the Ganges. We remained here in a state of tranquility, occasionally enjoying all the rural pleasures of the delightful country around us. After a stay of a few months, we received orders from Colonels Morgan and Goddard, to march hence to Monghere [Monghyr]; and Messieurs Baker, Scott, Besnard and the Artillery Quarter Master, set out before the army, between one and two o'clock in the morning, with the baggage and military stores, in the middle of the year 1771. We continued on the march near a month, and when we came within thirty miles of Monghere, a small antique house, built on a rock in the middle of an island, in the Ganges, attracted our notice: we halted towards the close of the evening, at some distance from it: the next day, Mr. Baker, Mr. Besnard, and the other Gentlemen, made a hunting match: I accompanied them: and about noon, after the diversion was over, we turned our horses towards the water side, and taking a nearer view of this solitary little mansion, resolved on crossing the river.

We gave our horses in charge to the sahies or servants, who have always the care of them, and passed over to the island in one of the fishing boats that ply here. When we advanced towards the hermitage, which, as an object of curiosity, is much frequented by travellers, the Faquir or Hermit, who held his residence here for many years, came out to meet us: he wore a long robe of saffron colour muslin down to his ancles, with long loose sleeves, and on his head a small mitre of white muslin, his appearance was venerable from a beard that descended to his breast; and though the hand of time conferred some snowy honours on his head, that negligently flowed down his shoulders a considerable length, yet in his countenance you might read, that health and chearfulness were his companions: he approached us with a look of inconceivable complacency tempered with an apparent serenity of mind, and assured us that whatever his little habitation could afford, he was ready to supply us with. While he was thus speaking, he seemed to turn his thoughts a little higher; for with eyes now and then raised towards Heaven, he continued to count a long bead that was suspended from his wrist; and he had another girt about his waist. We went with him into his dwelling, which was one of the neatest I have ever seen; it was quite square, and measured from one angle to the other, not more than five yards: it rose to a great height, like a steeple, and the top was flat, encompassed with battlements, to which he sometimes ascended by a long ladder. At certain hours in the day, he stretched in a listless manner on the skin of some wild animal, not unlike a lion's, enjoying the pleasure of reading some favourite author. In one corner of the house, he kept a continual fire, made on a small space between three bricks, on which he dressed his food that consisted mostly of rice, and the fruits of his garden; but whatever was intended for his guests, was laid on a larger fire outside the door. When we spent a little time in observing every thing curious inside his residence, he presented us some mangoes and other agreeable fruit, which we accepted; and parted our kind host, having made him some small acknowledgment for his friendly reception, and passed encomiums on the neatness of his abode and the rural beauty of his garden.

We passed over to the continent in a boat, belonging to the Faquir, that conveyed provisions from the island to the people passing up and down the river, who left him in return such commodities as he most wanted; and joined the army, which arrived early the following day at Monghere.

The European brigade marched into a fine spacious barrack: and the Seapoys into the chaumnies inside the fort, which is near two miles in circumference, and built on the Ganges in a square form, with the sides and front rising out of the water, and overlooking all the country seats along the coast.

The Officers' apartments in the front, were laid out with the greatest elegance; the soldiers', quite compact; and nothing could be handsomer than the exterior appearance of the building, which was of glittering hewn stone. The old palace of Cossim Alli Cawn [Mir Kasim Ali Khan], inside the ramparts, still uninjured by the waste of time, was put in order for the residence of Colonel Grant. The entrance into the fort was by four wide gates, constructed in a masterly manner; one at each side, opening into the barrack yard. It was originally built by some of the Nabobs; but since it came into the possession of the Company, it has served as a proper place for our cantonments. There are no other structures of any figure here. About a mile hence is a long row of low, obscure huts (such as the common natives inhabit in several parts of India) occupied by a class of people who prepare raw silk; and, at a little distance from them, reside the manufacturers. The people, in general, here, are remarkably ingenious, at making all kinds of kitchen furniture, which they carry to such an extent, as to be enabled to supply the markets in the most opulent cities around them; and are in such esteem, that they even send for them from Calcutta, and other parts of Bengal. There is a description of inhabitants in this country, who supply the markets, and have continued in this employment through many succeeding generations, always dwelling in one place; and others who follow the army under the denomination of bazars.

| • | • | • |

Letter VIII

Dear Sir,

There are some very fine seats and villas round Monghere, built by European Gentlemen in the Company's service, who retire to the country in the warm months of the year: among others, is the house of Mr. Grove, an elegant building finished in the English style, and standing in the centre of every rural improvement; a mile hence is the residence of Mr. Bateman, a very handsome structure, where we spent a few pleasant days in the most polite circles: amid such scenes, the riches and luxury of the East, are displayed with fascinating charms. Our host was that elevated kind of character, in which public and private virtues were happily blended; he united the Statesman with the private Gentleman; the deep Politician with the social Companion; and though of the mildest manners, he was brave in an eminent degree having led the way to victory in many campaigns. Twelve miles from Monghere, is a famous monument erected on a hill called Peepaharea [Pirpahar], which the love of antiquity induced us to visit: it is a square building, with an arch of hewn stone rising over a marble slab, supported by small round pillars of the same, without any inscription: and what is very remarkable, a large tiger, seemingly divested of the ferocity of his nature, comes from his den at the foot of the hill, every Monday and Wednesday, to this very monument, without molesting any person he meets on the way, (even children are not afraid to approach him) and sweeps with his tail, the dust from the lower part of the tomb, in which, it is supposed, are enshrined the remains of some pious character, who had been there interred at a remote period of time. The people have a profound veneration for it, which has not been a little increased by the sudden and untimely fate of a Lieutenant of Artillery, who came hither to indulge an idle curiosity, and ridicule those who paid such respect to the memory of their supposed holy man, who had been deposited here. He imputed their zeal to the force of prejudice and superstition, and turned it into such contempt, that he made water on the very tomb that was by them held sacred: but shortly after, as if he had been arrested by some invisible hand, for his presumption, having rode but a few paces from the tomb, he was thrown from his horse to the ground, where he lay some time speechless; and being conveyed to Monghere on a litter, soon after his arrival expired. Here is an awful lesson to those who, through a narrowness of judgment and confined speculation, are too apt to profane the piety of their fellow-creatures, merely for a difference in their modes of worship. At a little distance from Peepaharea was the bangaloe of Gen. Barker, constructed by him on the most elegant plan. Here he retired to spend some part of the summer, and entertain his friends: it was resorted by the distinguished Officers of his corps, and particularly by Colonels Grant, Morgan, Goddard, Tottingham, and Majors Morrison and Pearce, of the Artillery. At other times, he resided in a stately edifice in the fort, newly built, with exquisite taste and grandeur. Having received orders from Colonel Grant, to proceed to Calcutta, we made the necessary preparations for marching, and set out from Monghere in the beginning of the year 1772. The first day, we reached Sitakund, (where we halted three days) to collect our market people, &c. It is a small village, about twelve miles from Monghere, and in its environs are seven baths or wells, two of which are committed to the care of Bramins, who attend them, and will not suffer any person out of their order, to touch the waters, but such as come with a stedfast faith in their virtues (which they generally possess) to be relieved from various disorders by their application. The other five are common to all who travel this way. The two first are near each other, though very different in their qualities: the water of the one which is of a whitish colour, having an agreeable cool taste, while that of the adjacent well being of a darker hue, is continually boiling up. The people of the country make the most frequent use of them, and the Bramins, who dispatch their orders to all quarters round them in earthen jars filled at their hallowed founts, considerably benefit by their pious credulity. They even send it to the north of the Ganges; and it is held in holy veneration by the Hindoos in Calcutta, and the other districts of Bengal.

As we were advancing on our march, we met a number of Hindoo pilgrims proceeding on their journey to Sitakund, and reached Bohogolpore [Bhagalpur], in about fifteen days after we left Monghere. We encamped outside the town, which is, by no means, inconsiderable for its manufactures. It has a mud fort thrown round it, and contains a regiment of militia, to protect its trade, consisting of a famous manufactory of fine napkins, table cloths, turbans and soucy, a kind of texture composed of silk and cotton, some of which is beautifully variegated with stripes, and some of a nankin colour, used mostly by the Ladies of the country for summer wear. Governor Pelham, who commanded here, entertained our Officers in a very splendid manner. We halted four or five days to refresh our army, and during the time, the Cooleys were employed to clear and level the rugged narrow road, from Bohogolpore through Skilligurree [Siclygully]. Before we set out, we perceived that Captain Brook [Brooke], a very active Officer, at the head of five companies of Seapoys, stationed in the different parts of the neighbouring country, had been, some time, engaged in the pursuit of the Pahareas, a savage clan that inhabit the mountains between Bohogolpore and Rajamoul [Rajmahal], and annoy the peaceable resident and unwary traveller: numbers, happily! were taken, through the indefatigable zeal of the above Gentlemen, and justly received exemplary punishment; some being severely whipped in a public manner; and others, who were found to be more daring and flagitious, suspended on a kind of gibbets, ignominiously exposed along the mountain's conspicuous brow, in order to strike terror into the hearts of their accomplices.

| • | • | • |

Letter IX

Dear Sir,

Hence as we proceeded on our march, we beheld the lifeless bodies of these nefarious wretches elevated along the way for a considerable distance, about half a mile from each other; and having passed through the lofty arches or gateways of Sikilligurree and Tellicgurree [Tiliagarhi] planted with cannon, and erected by former Nabobs, as a kind of battery against the hostile invasions of those Mountaineers, we reached Rajamoul, where we remained a few days.

Our army being very numerous, the market people in the rere were attacked by another party of the Pahareas, who plundered them, and wounded many with their bows and arrows: the picquet guard closely pursued them, killed several, and apprehended thirty or forty, who were brought to the camp. Next morning, as our hotteewallies, grass cutters, and bazar people, went to the mountains about their usual business of procuring provender for the elephants, grass for the horses, and fuel for the camp; a gang of those licentious savages, rushed with violence on them, inhumanly butchered seven or eight of our people, and carried off three elephants, and as many camels, with several horses and bullocks. Such of our hotteewallies, &c. as were fortunate enough to escape with their lives from those unfeeling barbarians, made the best of their way to the camp, and related the story of their sufferings to the Commanding Officer, who kindled into resentment at the recital, instantly resolved to send the three Quarter Masters with two companies of Seapoys, in the pursuit of the lawless aggressors, some of whom, they luckily found ploughing in a field, to which they were directed by two of the men whom Providence rescued from their cruelty; and observed numbers flocking from the hills to their assistance: our men, arranged in military order, fired on them; some of the savages fell on the plain, others were wounded; and the greater part of them, after a feeble resistance with their bows, arrows, and swords, giving way to our superior courage and discipline, fled to the mountains for shelter, and raised a thick cloudy smoke, issuing from smothered fires, in order to intercept our view, and incommode us. Our gallant soldiers, swift as the lightning's flash, pursued, overtook, and made two hundred of them prisoners, who were escorted to Head Quarters, and by order of Colonel Grant, severely punished for their crimes; some having their ears and noses cut off, and others hung in gibbets. Their bows and arrows, and ponderous broad swords that weighed at least, fifteen pounds each, of which they were deprived, were borne in triumph as trophies of the little victory. Two of our hotteewallies, supposed to be massacred by them before this expedition, were found in a miserable state from their unmerciful treatment: they were endeavouring to crawl to the camp, disabled, and almost bleeding afresh from their recent wounds. The elephants, camels, &c. which those useful people took with them, for the purpose of bringing certain supplies to the army, were left behind in the hurry of the sanguinary and rapacious enemy's flight, cruelly mangled and weltering in their blood: our very horses and bullocks had iron spikes driven up in their hoofs, from which they must have suffered extreme torture. They were all, with some difficulty, brought back to the camp, and though taken every possible care of, a few only of the animals were restored, and the rest died in the anguish of exquisite pain.

We continued our march towards Calcutta; and on our way thither, encamped at Gouagochi [Godagarhi], which takes its name from a large black fort built on the banks of the Ganges, three miles from the place of our encampment, where we remained about two months. Our situation was extremely pleasant; the tents being almost covered with the spreading branches of mangoe and tamarind trees, which under the rigours of a torrid sun, afforded a cool shade, and brightened the face of the surrounding country; whilst the Ganges, to heighten the beauty of the varied landscape, rolled its majestic flood behind us. Hence we went to Dumdumma [Dumdum], where we had a general review. Governor Cottier [Cartier] came from Bengal in order to see it, with his Aid-du-Camps, and a numerous train of attendants: his entry into Dumdumma was very magnificent: he was accompanied by our Colonel and some of the principal Officers, who met him on the way: all the army were drawn up, and received him with a general salute. The entire night was spent in preparations for our appearance next day: every individual was employed; and at four o'clock, on the coming morn, we were all on the plain in military array, with twenty field pieces, attended by two companies of Artillery: not a man, through the whole of the business, in which we took up several acres of ground, but displayed uncommon abilities; and was rewarded for his exertions, by the unanimous consent of the Officers, with an extra allowance of pay and refreshment. The natives, who flocked from all quarters, for many miles around, were delighted and astonished at the sight——

Of martial men in glitt'ring arms display'd, And all the shining pomp of war array'd; Determin'd soldiers, and a gallant host, As e'er Britannia in her pride cou'd boast.

The General received the Governor's compliments on the occasion, who declared that such brave fellows never before adorned the plains of Asia. The review was over at twelve o'clock, when all the Gentlemen were invited to breakfast with the General. The men, overjoyed with the approbation of their Officers, retired to their tents to talk over their military atchievements, and form, by the creative power of fancy, a second grand review round their copious bowls of Arrack, a generous, exhilarating liquor, distilled from the fruit of the tree that bears the same name. The Governor remained a few days here, and was entertained in a style of elegant hospitality, by the military Gentlemen and the most distinguished Personages of the country. The scene of their convivial festivity, was the former habitation of a grand Nabob of this place, constructed on an ancient plan, and containing a number of spacious apartments; but from the change it received from the hand of recent improvement, it had more the appearance of a modern European mansion, than an uncouth pile of building, that reared its gothic head in remoter time.

| • | • | • |

Letter X

Dear Sir,

Shortly after the review was over, we marched from Dumdumma to Calcutta, where we arrived in the year 1772. The first brigade that lay in Fort William, and thence proceeded to Denapore, was relieved by a part of our army (which formed the third brigade) consisting of one battalion of Europeans that marched into the fort, and three regiments of Seapoys that occupied the chaumnies at Cheitpore; the other battalion of Europeans, to which Mr. Baker belonged, and three regiments of Seapoys, were ordered to Barahampore [Baharampur], after some short stay here.

Calcutta is a very flourishing city, and the presidency of the English Company in Bengal. It is situate on the most westerly branch of the less Ganges in 87 deg. east lon. and 22, 45 north lat.; 130 miles north east of Balisore, and 40 south of Huegley [Hoogly]. It contains a number of regular and spacious streets, public buildings, gardens, walks, and fish ponds, and from the best accounts, its population has advanced to upwards of six hundred thousand souls. The principal streets are the Chouk, where an endless variety of all sorts of goods are sold; the China Bazar, where every kind of china is exposed to sale; the Lalbazar, Thurumthulla [Dharamtala], Chouringee [Chowringhee], Bightaconna [Baitakkhana], Mochoabazar [Machuabazar], and Chaunpolgot [Chandpal Ghat], where the European Gentlemen, of every description, mostly reside. The greatest concourse of English, French, Dutch, Armenians, Abyssinians, and Jews, assemble here; besides merchants, manufacturers, and tradesmen, from the most remote parts of India.

Near Chaunpolgot is the old fort, which contains the Company's stores garrisoned by the invalids and militia, and inhabited by Collectors, Commissaries, Clerks, and in my time by a Mr. Paxon, the Director or Superintendant of the people employed in the mint, to coin goulmores, rupees, and paissays. Fort William is a mile from the town, and the most extensive in India. The plan of it was an irregular tetragon, built with brick and mortar made of brick dust, lime, molasses, and hemp, a composition that forms a cement as hard and durable as stone. The different batteries surrounding it, are planted with about six hundred cannon: and its inner entrance is by six gates, four of which are generally left open: outside these are fourteen gate-ways leading through different avenues, to the inner gates severally situate in opposite directions to the river, the Hospital, Kidderpore, and Calcutta. Near each gate is a well, from which water is easily raised for the use of the army by engines happily contrived for that purpose. The Commander in Chief resides in an elegant edifice within the fort, where there is also a bazar constantly held to supply the army with every necessary: and the Officers of rank next to him, dwell on the very arches of the gates, in beautifully constructed buildings, that, in such elevated situations, have a very fine effect on the delighted beholder. Inside the fort there are eight barracks, for the other Officers and privates; stores for the ammunition and accoutrements; magazines, armories, and a cannon and ball foundry, almost continually at work, for the general use of the Company's troops throughout India. In short, Fort William is an astonishing piece of human workmanship, and large enough to contain, at least, ten thousand inhabitants.

The other principal public buildings, are the Court-Houses, Prisons, and Churches. There are three Court-Houses; one fronting Loldigee, one near the Governor's mansion, and the other in Chaunpolgot: two prisons; one in Lalbazar, and another in Chouringee: and several Churches, besides the English, Armenian, and Portuguese, which are the most noted places of worship, in point of magnitude, exterior figure, and decoration. On the opposite side of the river are docks for repairing and careening ships; and outside the town is an hospital, encompassed by a sheltering grove; some pleasant villas, the summer retreats of the European Gentlemen, delightful improvements, aromatic flower gardens, winding walks planted with embowering trees on each side, and fish ponds reflecting, like an extended mirror, their blooming verdure on each margin, and Heaven's clear azure in the vaulted canopy above. There is also a very fine canal formed at the expense of Mr. Tolly, which is navigable for boats passing up and down: it was cut through the country, and extended from Kidderpore to Culman [Kalna], a distance of five or six miles, connecting the Ganges with the river Sunderbun [Sunderbans]. Mr. Tolly benefited considerably by this mode of conveyance; as it was deemed more convenient than that of land carriage, and became the principal channel of conveying goods to different parts of Bengal.

| • | • | • |

Letter XI

Dear Sir,

Our stay in Calcutta was so short, that I have been only able to give you some account of the town, forts, and environs; and am concerned that I could not contribute more to your entertainment, by a description of the manners of the people, as we received too sudden orders to march to Barahampore, where we arrived in the year 1773, having met with no extraordinary occurrence on the way. The cantonments here are situate on the banks of the river Bohogritee [Bhagirathi], and consist of twenty-two barracks, besides a magazine, stores, and offices. There are two barracks on the south near the river, in which the Colonels and Majors reside: six on the east, and six on the west, occupied by the other Officers: in the northern direction, the privates of the Artillery and Infantry Corps dwell: the Commander in Chief has a superb building, about a mile from the barrack of the privates; and the intermediate space between the different barracks, which form a square, is a spacious plain where the men exercise. Barahampore is very populous, and connects with Muxadabad [Murshidabad] by an irregular chain of building, comprehending Calcapore [Kalkapur] and Casambuzar [Cossimbazar], two famous manufactories of silk and cotton, where merchants can be supplied on better terms than in any other part of India. The city of Muxadabad, to which I had been led by curiosity, is the mart of an extensive trade among the natives, such as the Moguls, Parsees, Mussulmen, and Hindoos; the houses are neat, but not uniform; as every dwelling is constructed according to the peculiar fancy of the proprietor: those of the merchants are, in general, on a good plan, and built of fine brick made in the country; and such as have been erected by the servants of the Company, near the town, are very handsome structures. The city, including the suburbs, is about nine miles in length, reaching as far as Barahampore; and the neighbouring country is interspersed with elegant seats belonging to the Governors, and other Officers; among which, was the Nabob Mamarah Dowlah's [Mubarak al-Daula's] palace, finished in a superior style to the rest, and surrounded with arched pillars of marble, decorated with variegated purdoes—over the arches, native bands of music played on their different instruments, every morning and evening—on one side of the palace flowed the river Bohogritee in winding mazes: on the other, stood the Chouk, where people assembled to sell horses, wild and tame fowl, singing birds, and almost every product and manufacture of India.

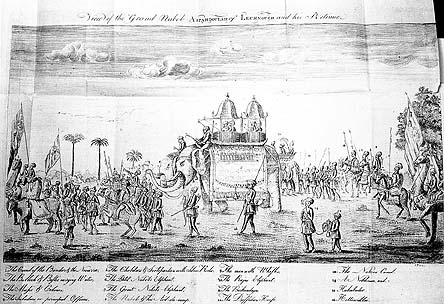

Soon after my arrival here, I was dazzled with the glittering appearance of the Nabob, and all his train, amounting to about three thousand attendants, proceeding in solemn state from his palace to the temple. They formed in the splendor and richness of their attire one of the most brilliant processions I ever beheld. The Nabob was carried on a beautiful pavillion, or meanah, by sixteen men, alternately, called by the natives, Baharas, who wore a red uniform: the refulgent canopy covered with tissue, and lined with embroidered scarlet velvet, trimmed with silver fringe, was supported by four pillars of massy silver, and resembled the form of a beautiful elbow chair, constructed in oval elegance; in which he sat cross-legged, leaning his back against a fine cushion, and his elbows on two more covered with scarlet velvet, wrought with flowers of gold. At each side of his magnificent conveyance, two men attended with large whisks in their hands, made of some curious animal's tail, to beat off the flies. The very handles of those whisks were of silver. As to the ornaments of his person—he wore a very small turban of white muslin, containing forty-four yards, which quantity, from its exceeding fineness, would not weigh more than a pound and half; a band of the same encompassed his turban, from which hung silver tassels over his right eye: on the front was a star in diamond of the first water: a thin robe of fine muslin covered his body, over which he wore another of cream-coloured satin, and trousers of the same, trimmed with silver edging, and small silver buttons: a valuable shawl of camel's hair, was thrown negligently about his shoulders; and another wrapped round his waist: inside the latter, he placed his dagger, that was in itself a piece of curious workmanship, the hilt being of pure gold, studded with diamonds, and embellished with small chains of gold.

His shoes were of bright crimson velvet, embroidered with silver, and set round the soals and binding with pearls. Two Aid-du-Camps, one at each side, attended him on horseback; from whom he was little more distinguished in splendor of habiliment, than by the diamond star in his turban. Their saddles were ornamented with tassels, fringe, and various kinds of embroidery. Before and behind him, moved in the pomp of ceremony, a great number of pages, and near his person slowly advanced his life guard, mounted on horses: all were clad in a stile of unrivalled elegance: the very earth with expanding bosom, poured out her treasures to deck them; and the artisan essayed his utmost skill to furnish their trappings.

His pipe was of a serpentine form, nine cubits in length, and termed hooka: it reached from his lips, though elevated his situation above the gay throng, to the hands of a person who only walked as an attendant in the train, for the purpose of filling the silver bowl with a nice compound of musk, sugar, rose-water, and a little tobacco finely chopped, and worked up together into a kind of dough, which was dissolved into an odoriferous liquid by the heat of a little fire made of burnt rice, and kept in a silver vessel with a cover of the same, called Chilm, from which was conveyed a fragrant cool smoke, through a small tube connecting with another that ascended to his mouth.

The part which the attendant held in his hand, contained at least a quart of water: it was made of glass, ornamented with a number of little golden chains admirably contrived: the snake which comprehends both tubes was tipped with gold at each end, and the intermediate space was made of wire inside a close quilting of satin, silk, and muslin, wrought in a very ingenious manner: the mouth piece was also of gold, and the part next to his lips set with diamonds.

A band of native music played before him, accompanied with a big drum, conveyed on a camel, the sound of which, could be heard at a great distance: and a halcorah or herald advanced onward in the front of the whole company, to proclaim his arrival, and clear the way before him. Crowds of people from every neighbouring quarter, thronged to see him. I waited for some time, to see him enter into the temple with all his retinue, who left their shoes at the door as a mark of veneration for the sacred fane into which they were entering. The view of this grand procession, gave me infinite pleasure, and induced me to continue a little longer in Muxadabad.

| • | • | • |

Letter XII

Dear Sir,

Shortly after the procession, I met with a relation of mine, a Mahometan, who requested my attendance at the circumcision of one of his children. Previous to this ceremony, which I shall describe in the order of succession, it may be necessary to premise, that a child is baptized three times according to the rites of this religion. The first baptism is performed at time of the birth, by a Bramin who, though of different religious principles, is held in the utmost veneration by the Mahometans, for his supposed knowledge in astrology, by which he is said to foretel the future destiny of the child; when he discharges the duties of his sacred function on such an occasion, which consists in nothing more than this prophecy, and calling the child by the most favourable name, the mysteries of his science will permit, he receives some presents from the parents and kindred, and retires.

The second baptism, which takes place when the child is four days old, is performed by the Codgi, or Mulna, the Mahometan Clergyman, in the presence of a number of women, who visit the mother after her delivery; he first reads some prayers in the alcoran, sprinkles the child with consecrated water, and anoints the navel and ears with a kind of oil extracted from mustard seed, which concludes the ceremony. The Priest then quits the womens' apartment, and joins the men in another room. When he has withdrawn, the Hajams' wives enter the chamber, and attend the mother of the child with every apparatus necessary in her situation: one assists to pare her nails, and supplies her with a bason of water to wash her hands in; and others are employed in dressing her in a becoming manner. Several Ladies of distinction come to visit her, presenting her their congratulatory compliments on her happy recovery, and filling her lap, at the same time, with a quantity of fresh fruit, as the emblem of plenty. When this ceremony is over they sit down to an entertainment served up by the Hajams' wives, and prepared by women in more menial offices. Their usual fare is a variety of cates and sweetmeats. The men, who also congratulate the father, wishing every happiness to his offspring, are regaled much in the same manner. Thus is the second baptism celebrated; from which the third, which is solemnized on the twentieth day after the birth, differs only in point of time.

The Mahometans do not perform the circumcision, or fourth baptism until the child is seven years old, and carefully initiated in such principles of their religion as can be well conceived at such a tender age. For some time before it, the poorer kind of people use much oeconomy in their manner of living, to enable them to defray the expenses of a splendid entertainment, as they are very ambitious of displaying the greatest elegance and hospitality on such occasions. When the period of entering on this sacred business is arrived, they dispatch Hajams or Barbers, who from the nature of their occupation are well acquainted with the city, to all the inhabitants of the Mahometan profession, residing within the walls of Muxadabad, to whom they present nutmegs, which imply the same formality as compliment cards in this country. The guests thus invited assembled in a great square, large enough to contain two thousand persons, under a semiana of muslin supported by handsome poles erected at a certain distance from each other; the sides of it were also made of muslin, and none would be suffered to enter but Mahometans. The arrival of the Mulna was announced by the Music, who had a kind of orchestre within the semiana: attended by one of the Hajams, he approached the child who was decked with jewels and arrayed in scarlet muslin, and sat under a beautiful canopy richly ornamented with silk hangings, on an elegant elbow chair with velvet cushions to the back and sides, from which he was taken and mounted on a horse, accompanied by four men, his nearest relations, each holding a drawn sword in his hand, who also wore a dress of scarlet muslin. People of condition, among the Mahometans, contribute largely to the magnificence of this ceremony; and appear on horseback in the midst of the gay assembly, with their finest camels in rich furniture led after them.

But to return—the child was conducted in this manner to a chapel, at the door of which he alit, assisted by his four relations, who entered with him into the sacred building, where he bowed in adoration to one of the Prophets, repeating with his kindred, some prayers he had been before taught by his parents; after this pious duty is over, he is again mounted on his horse, and led to another chapel, where he goes through the same forms, and so on to them all, praying with the rest of the company, and fervently imploring in the attitude of prostrate humility, the great Alla to protect him from every harm in the act of circumcision.

After they had taken their rounds to the different places of worship, they returned to the square in which the semiana was erected, and placed him under the glittering canopy, upon his accustomed chair. The music that played before him suddenly ceased, when the Mulna appeared in his sacredotal robes, holding a silver bason of consecrated water, with which he sprinkled him; while the Hajam slowly advancing in order to circumcise him, instantly performed the operation. In this critical moment, every individual in the numerous crowd, stood on one foot, and joined his father and mother in heartfelt petitions to Heaven for his safety. The Music again struck up, and played some cheerful airs: after which, the child was taken home by his parents and put to bed. The company being served with water and napkins by the Hajams, washed their hands and sat down barefooted on a rich carpet, to partake of a favourite dish called by the natives pelou, composed of stewed rice and meat highly seasoned, which they are in general fond of. The entire scene was illuminated with torches, which, by a strong reflexion of artificial lustre, seemed to heighten the splendor of their ornaments.

| • | • | • |

Letter XIII

Dear Sir,

I shall now proceed to give you some account of the form of marriage among the Mahometans, which is generally solemnized with all the external show of Oriental pageantry. The parents of the young people, first treat on the subject of uniting them in the bands of wedlock, and if they mutually agree on a connection between them, the happy pair, who were never permitted to see each other, nor even consulted about their union, are joined in marriage at a very youthful time in life, the female seldom exceeding the age of twelve, and the lad little more advanced in years: they must always be of the same cast, and trade; for a weaver will not give his daughter to a man of any other occupation: in the higher scenes of life, each of the parties bring a splendid fortune; but among people of the middle class, the woman has seldom more allotted her than her apparel, furniture, and a few ornaments of some value, as the parents of the man provide for both, by giving him a portion of such property as they can afford; in land, merchandize, or implements of trade, according to their situation. When they conclude all matters to their satisfaction, Hajams are sent with nutmegs, in the usual form, to invite their friends and acquaintance to the wedding, and the houses of each party are adorned with green branches and flowers. Outside the doors they erect galleries for the musicians, under which, are rows of seats or benches for the accommodation of the lower class of people, who are forbid any closer communication. Allured by invitation and the love of pleasure, the welcome guests arrive, and discover the houses by the green branches and flowers with which they are gayly dressed, to distinguish them from others. The entire week is spent in the utmost mirth and convivial enjoyment. The finest scarlet muslin is procured for the young people and their relations, by their parents on both sides: those of the youth supply the dresses of the young woman and her kindred; and her's furnish him and his relatives with suitable apparel.

Thus arrayed, the bridegroom is carried on a palanquin, with lighted torches in his train, attended by a number of people, to the house of the bride, whose friends meet him on the way. At his arrival, the ceremony is performed, if the mansion be large enough to contain the cheerful throng that assemble on this festive occasion; if not, which is generally the case, a semiana is erected in a spacious square, in the centre of which is a canopy about seven feet high, covered on the top with the finest snow-white muslin, and decorated inside with diversified figures representing the sun, moon, and stars. Beneath this temporary dome, the coy maid reclines on a soft cushion, in an easy posture, while the raptured youth, scouring through fancy's lawn, on the wings of expectation, and already anticipating the joys of connubial felicity, leans opposite his sable Dulcinea in a similar attitude. The breathing instruments now wake their trembling strings to announce the coming of the Mulna, who enters the scene with an air of characteristic solemnity: the music gradually ceases, till its expiring voice is lulled into a profound silence; and the Priest opens the alcoran, which is held according to custom by four persons, one at each corner, and reads, in grave accents, the ceremony. The bride and bridegroom interchange rings, which they put on their fingers; and one of the bridemaids, supposed to be her relation, comes behind both, who are veiled, and ties, in a close knot, the ends of their shawls together, to signify their firm union. The Mulna, finally, consecrates a glass of water and sugar, which he presents to them: they alternately taste it, but the man gives it round to a few select friends of the company, who, in turn, put it to their lips, wishing happiness to the married couple. They now sit down to an elegant supper, after which the dancing girls are introduced, who make a splendid appearance, clothed in embroidered silks and muslins, and moving in a variety of loose attitudes that allure admiration and excite the passions.

When the entertainment is over, a silver plate not unlike a salver, is carried about, into which almost every individual drops some pecuniary gratuity to reward the trouble of the Hajams, and the guests retire in company with the newly wedded pair, who are conveyed on separate palanquins to the house of his father, while bands of music in cheerful mood are playing before them, numerous torches flaming round them, that seem with their blaze to disperse the gloom of night, and fire-works, exhibiting in the ambient air, a variety of dazzling figures. When they arrive, the Mulna gives them his benediction, and sprinkles the people about them, with perfumed water coloured with saffron: a second entertainment is then prepared for their friends and acquaintance, which concludes the hymeneal festivity. Among people of rank, merchants, and tradesmen, who have made any acquisitions, in life, the Lady never goes outside the doors after marriage, except when she is carried on a palanquin, which is so well covered that she cannot be seen by any body. A man of any consequence in India, does not stir out for a week after his nuptials, and would deem it dishonourable to suffer his wife to appear in public: the indigence of the poorer kind of people precludes them from the observance of this punctilio. The husband's entire property after his decease, comes into the possession of his wife. It may be here observed, that the Hindoo, as well as the Mahometan, shudders at the idea of exposing women to the public eye: they are held so sacred in India, that even the soldier in the rage of slaughter will not only spare, but even protect them. The Haram is a sanctuary against the horrors of wasting war, and ruffians covered with the blood of a husband, shrink back with confusion at the apartment of his wife.

| • | • | • |

Letter XIV

Dear Sir,

The Mahometans are, in general, a very healthful people: refraining from the use of strong liquors, and accustomed to a temperate diet, they have but few diseases, for which their own experience commonly finds some simple yet effectual remedy. When they are visited by sickness, they bear it with much composure of mind, partly through an expectation of removing their disorder, by their own manner of treating it: but when they perceive their malady grows too violent, to submit even to the utmost exertions of their skill, they send for a Mulna, who comes to the bedside of the sick person, and putting his hand over him, feels that part of his body most affected, and repeats, with a degree of fervency, some pious prayers, by the efficacy of which, it is supposed the patient will speedily recover. The Mahometans meet death with uncommon resignation and fortitude, considering it only as the means of enlarging them from a state of mortal captivity, and opening to them a free and glorious passage to the mansions of bliss. Those ideas console them on the bed of sickness; and even amid the pangs of dissolution, the parting soul struggling to leave its earthly prison, and panting for the joys of immortality, changes, at bright intervals, the terrors of the grim Monarch into the smiles of a Cherub, who invites it to a happier region.