Preferred Citation: Hart, John. Storm over Mono: The Mono Lake Battle and the California Water Future. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1996 1996. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft48700683/

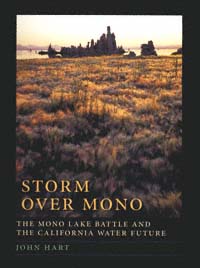

| Storm over MonoThe Mono Lake Battle and the California Water FutureJohn HartUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1996 The Regents of the University of California |

In memory of my mother and best colleague

JEANNE McGAHEY HART

1906–1995

Preferred Citation: Hart, John. Storm over Mono: The Mono Lake Battle and the California Water Future. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1996 1996. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft48700683/

In memory of my mother and best colleague

JEANNE McGAHEY HART

1906–1995

Acknowledgments

The lengthy preparation of this book was made possible by Watermark, a consortium of persons who wish to see this complex story told as fully as possible. Through Watermark, Gerda Mathan provided invaluable new portrait photography for the project and Joan Rosen took on the major task of pulling together the color images. My thanks.

When I began work, the Mono Lake controversy was approaching its climax. I found myself writing a mixture of history and news. Many people who figure in the tale took the time to inform and advise me even in the midst of battle; I am grateful to all of them.

At the top of the list must come three key and continual informants: Mono Lake Committee Executive Director Martha Davis, geomorphologist Scott Stine, and hydrologist Peter Vorster. These experts gave me material enough for a book apiece, and none of them can be quite satisfied with mine. Any outright mistakes that occurred in the compression go of course to the author's account.

At the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, I've had the generous assistance of Mitchell Kodama, departmental point man on Mono affairs. Thanks also to James F. Wickser, Dennis C. Williams, Kenneth W. Downey, Gerald A. Gewe, Valerie Roberts Gray, Steve McBain, Brian White, and the capable staffs of the library and the photo archive. I had most helpful conversations with former department leaders Mike Gage, Duane Georgeson, and Mary Nichols, and with Los Angeles City Council members Ruth Galanter and Zev Yaroslavsky.

On legal matters I'm indebted especially to Virginia A. Cahill, Harrison C. Dunning, Patrick Flinn, Cynthia L. Koehler, Barrett McInerney, Richard Roos-Collins, Jan S. Stevens, and Tim Such; also to Bruce Dodge, Stan Eller, Judge Edward Forstenzer, Joe Krovoza, Palmer Brown Madden, Antonio Rossmann, Joseph L. Sax, Mary J. Scoonover, Laurens Silver, and Bryan J. Wilson.

In Lee Vining and the eastern Sierra, I've had many hosts and informants. I must mention first Sally Gaines, Ilene Mandelbaum, and John Cain; among many other favors, John jeeped me up the steep road to Mono Dome and around the lake's mysterious east side. Warm thanks also to Jerry and Terry Andrews, Don Banta, Carlisle Becker, Jim Edmondson, Scott English, Brian Flaig, Augie Hess, Rick Knepp, Andrea Lawrence, Wallis R. McPherson, Geoffrey McQuilkin, Sally Miller, Shannon Nelson, Arlene Reveal, E. Woody Trihey, and all the staff of the Mono Lake Committee offices in Lee Vining and Burbank.

On natural history, I've taken lessons from researchers Roy A. Bailey, Bob Curry, Gayle L. Dana, David B. Herbst, N. King Huber, Joseph R. Jehl, Jr., Kenneth Lajoie, David T. Mason, John M. Melack, David Shuford, and David W. Winkler.

My thanks to Barbara A. Bates of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; Thomas A. Cahill of the Air Quality Group, Crocker Nuclear Laboratory, University of California at Davis; Jim Canaday, environmental specialist with the State Water Resources Control Board; David Carle of the Mono Lake Tufa State Reserve; Marc Del Piero of the water board; Deana Dulen, Lucy McKee, Dennis Martin, and Nancy Upham of Inyo National Forest; LeRoy Graymer of the Public Policy Program at UCLA; Gary E. Smith of the California Department of Fish and Game; and Elden H. Vestal of that department (retired).

Pieces of the story were filled in by David Brower of the Earth Island Institute; Russ Brown and Tim Messick of Jones & Stokes; Hal Candee of the Natural Resources Defense Council; Thomas J. Graff of the Environmental Defense Fund; Assemblyman Phil Isenberg; Huey Johnson of the Resource Renewal Institute; George Peyton and Dan Taylor of the National Audubon Society; and Mono Lake Committee board members Ed Grosswiler, Dave Phillips, and Genny Smith.

More gaps were filled by Rick Battson, Michael Bowen of California Trout, Gray Brechin, Dick Dahlgren, Grace DeLaet, David de Sante, Cecilia Estolano, Joe Fontaine, Robert Golden, Brian Gray, Jeff Hansen, Jon S. Heim, Mike Jimenez, Stephen Johnson, Bob Jones of the Los Angeles Times , William L. Kahrl, Assemblyman Richard Katz, Louis Lee of the Los Angeles City Administrative Office, former Congressman Richard Lehman, Richard May, Jason Montiel of the Mammoth Review-Herald , Peter Moyle, Randy Pestor, Phil Pister, Betsy Reifsnider, Judge Ronald Robie, Mark Ross, Bob Schlichting, Jan Simis, Felix Smith, Jan Stevens, John Stodder, Dean Taylor, Michael Verzatt, and Dave Weiman.

In chasing sources and odd facts, I've relied on countless libraries and editorial staffs. It would be unpardonable not to mention at least Ann Crawford of the Geological Society of America, Joel Ellis of the Mono Basin National Forest Visitor Center, Barbara Gately of the Marin County Law Library, Vineca Hess of the Mono County Free Library, Shirley McDermott of Resources for the Future, Chris Renz of the National Geographic Society, and Laura Williams of the Point Reyes Bird Observatory.

Special thanks to the photographers for the use of their color and black-and-white images, and for letting them be held for many months as the story and the manuscript evolved.

The process of making a book out of it all was smoothed by John Evarts of Cachuma Press, Steve Fisher, Dane and Wendy Henas, Don Jackson, Dotty LeMieux, David Sanger, and Mary Anne Stewart. It has been a pleasure working with project editor Rose Vekony and copy editor Jane-Ellen Long at the University of California Press.

Some Characters of the Story

BILL BAKER Assemblyman, Republican of Danville, 1981–92, then representative. In 1989, joined with Democrat Phil Isenberg to help Los Angeles find replacements for Mono Basin water.

THOMAS W. BIRMINGHAM Attorney with Kronik, Moskovitz, Tiedemann, & Girard of Sacramento. In later years headed the Los Angeles legal team.

CECILY BOND Superior Court judge, Sacramento County. Her 1989 decision not to force early restoration of Mono Basin streams led to the momentous appellate court decision known as CalTrout II.

TOM BRADLEY Mayor of Los Angeles, 1973–93. This generally environment-minded Democrat was passive on the Mono Lake issue.

WILLIAM BREWER Member of the California State Geological Survey of 1860–64. Recorded his vivid impressions of the Mono Basin.

DAVID BROWER Veteran conservationist. Played a brief but important role in launching the Mono Lake public trust lawsuit in 1979.

EDMUND G. "PAT " BROWN State attorney general, 1951–58; governor, 1959–66. As attorney general, declined to enforce stream-protection laws; as governor, launched the State Water Project.

JERRY BROWN Governor, 1975–82. Promoted water law reform. See Harrison C. Dunning; Huey Johnson.

THOMAS A. CAHILL Researcher, University of California, Davis. From 1979, studied Mono Basin dust storms.

JIM CANADAY Biologist, State Water Resources Control Board. Coordinated the massive staff effort leading to Decision 1631 of 1994 restoring Mono Lake.

HILARY COOK Superior Court judge, Alpine County. The first judge in the Mono Basin cases and the one most attuned to the views of Los Angeles.

DICK DAHLGREN Fly fisherman. In 1984, caught brown trout in temporarily rewatered Rush Creek, triggering a second round of Mono Basin legal cases.

GAYLE L. DANA Biologist. She studied the unique Mono Lake brine shrimp and man-

aged to avoid becoming associated with a "side."

MARTHA DAVIS Mono Lake Committee executive director, 1984–95. Seeking compro-mise and negotiation, she had to settle for a stunning victory instead.

MARC DEL PIERO Member, State Water Resources Control Board. Presided at endless hearings in 1993 and 1994; largely drafted the 1994 lake-level decision.

BRUCE DODGE Attorney, Morrison & Foerster of San Francisco. From 1979, championed the cause of Mono Lake at his own firm and in a seemingly endless succession of courts.

WALTER DOMBROWSKI Hunter and naturalist. Ran a lodge at the mouth of Rush Creek and counted ducks on pre-diversion Mono Lake.

KENNETH W. DOWNEY Assistant city attorney, Los Angeles. Veteran warrior for the cause of the Department of Water and Power.

HARRISON C. DUNNING Law professor, University of California at Davis. In 1977–78, headed the staff of Jerry Brown's Governor's Commission to Review California Water Rights Law; saw how the public trust doctrine might be used to protect streams. A leading academic voice for water law reform.

FRED EATON Engineer; Los Angeles mayor; Long Valley rancher. Initiated the Los Angeles Aqueduct.

JIM EDMOSDSON Fly fisherman and conservationist. From 1990, oversaw the Mono Basin efforts of California Trout.

STAN ELLER Assistant district attorney, later district attorney, Mono County. In 1984, ordered Los Angeles to continue releasing water down Rush Creek.

JOHN FERRARO Los Angeles city councilman. In 1984, conducted hearings on the Rush Creek matter.

TERRENCE FINNEY Superior Court judge, Eldorado County. When the combined Mono cases came into his hands in 1989, he passed the major issues to the State Water Resources Control Board.

PATRICK FLINN Attorney, Morrison & Foerster, Palo Alto. Has spent his entire career to date working on Mono Lake.

EDWARD FORSTENZER Attorney, later Justice Court judge, Mono County. Launched Dahlgren v. Los Angeles in 1984.

MIKE GAGE President, Los Angeles Board of Water and Power Commissioners, 1990–92. Attempted to produce a Mono compromise but balked at the Mono Lake Committee's demands.

DAVID GAINES Activist. Co-founder and leading light of the Mono Lake Committee; died 1988.

SALLY (JUDY ) GAINES Activist and publisher. Co-founder of the Mono Lake Committee and, after David's death, co-chair.

RUTH GALANTER Los Angeles city councilwoman, 1987-. Became a leading voice for a resolution at Mono.

JOHN R. GARAMENDI State senator, Democrat of Stockton, 1976–90. Advocated Mono preservation.

DUANE L. GEORGESON Assistant general manager for Water, Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, 1982–90. In this and earlier departmental posts, confronted opponents in the Mono Basin and the Owens Valley.

THOMAS J. GRAFF Attorney, Environmental Defense Fund. In 1988, sought replacements in the Central Valley for Los Angeles's Mono Basin water.

LEROY GRAYMER Head, Public Policy Program, University of California at Los Angeles. Worked to mediate a settlement between the Mono Lake Committee and the Department of Water and Power.

ED GROSSWILER Executive director, Mono Lake Committee, 1982–84. Professionalized committee affairs and remained a key adviser for years.

DAVID B. HERBST Biologist. Nicknamed "Bug," he studied the Mono Lake alkali fly intensively.

PHILLIP ISENBERG Assemblyman, Democrat of Sacramento, 1983-. With Bill Baker, dangled money in front of Los Angeles to encourage a search for replacement water supplies.

JOSEPH R. JEHL , JR . Ornithologist. Documented the role of Mono Lake for grebes and phalaropes; clashed with David Winkler on the needs of California gulls.

HUEY JOHNSON Secretary of Resources to Governor Jerry Brown, 1978–82. Established the 1979 Interagency Task Force on Mono Lake.

STEPHEN JOHNSON Photographer. An early Mono Lake Committee activist, he launched the Bucket Walks and later curated the exhibit At Mono Lake .

LAWRENCE KARLTON Judge, Federal District Court, Sacramento. When Audubon v. Los Angeles strayed into his court, Audubon fought to keep it there.

RICHARD D. KATZ Assemblyman, Democrat of Los Angeles, 1981-. Pushed water law reform and efforts toward a solution to the battle over the lake.

KENNETH R. LAJOIE Geologist. Produced pioneering studies of the Mono Basin and led an early effort to preserve the lake.

PAUL H. LANE General manager and chief engineer, Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, 1983–89. His tenure at the top began with one legal setback, the 1983 public trust decision of the California Supreme Court, and ended with a second, CalTrout I.

ANDREA LAWRENCE MonoCounty supervisor; skier, conservationist. Founded Friends of Mammoth; serves on the board of the Great Basin Unified Air Pollution Control District.

RICHARD LEHMAN Representative, Democrat of Fresno, 1983–94. Led campaign for the Mono Lake National Forest Scenic Area; maintained federal interest in the alkali dust problem.

TIM LESLIE State senator, Republican of Lake Tahoe, 1984-. Represents Mono Basin; gave key support to the final settlement and water board decision:

JOSEPH B. LIPPINCOTT Engineer. As a federal irrigation bureaucrat, 1903–6, he worked against his own agency to capture the Owens River for Los Angeles.

WILLIAM McCARLEY General manager and chief engineer, Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, 1994-. Formerly an aide to Mayor Riordan, McCarley sought a quick settlement in the Mono Basin.

BARRETT W. McINERNEY Attorney and fly fisherman. Managed the Dahlgren case and later launched a full-scale attack on Los Angeles's Mono Basin licenses for California Trout.

PALMER BROWN MADDEN Attorney. With Tim Such and Bruce Dodge, an architect of Audubon v. Los Angeles .

DAVID T. MASON Limnologist. In the 1960s, did the first systematic modern research on Mono Lake and sought to stir up a campaign on its behalf.

JOHN M. MELACK Limnologist. Conducted research at Mono Lake from 1978 on.

GEORGE MILLER Representative, Democrat of Richmond, 1975-. Pushed water law reform; co-wrote the 1992 Miller-Bradley bill which, among much else, funded water reclamation in Los Angeles to replace Mono water.

NATE F. MILNOR President, California Fish and Game Commission, 1940. Executed an agreement with the Department of Water and Power allowing it to dry up streams, in violation of state law.

ADOLPH MOSKOVITZ Attorney, Kronik, Moskovitz, Tiedemann, & Girard of Sacramento. A noted exponent of traditional water law, he represented the Department of Water and Power in Mono matters from 1980.

WILLIAM MULHOLLAND Engineer. The brilliant first chief of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power who built the Los

Angeles Aqueduct, confronted rebellion in the Owens Valley, and laid plans for tapping the Mono Basin streams.

MARY NICHOLS Attorney. In 1979, at the California Air Resources Board, initiated Mono Basin air studies; in 1992, as a member of the Los Angeles Board of Water and Power Commissioners, sought compromise with the Mono Lake Committee.

DAVID OTIS Superior Court judge, Siskiyou County. In 1985, as a visiting judge, issued the first rulings in Dahlgren v. Los Angeles .

GEORGE PEYTON Attorney and National Audubon Society board member. Brought the organization into the center of the Mono Lake campaign and oversaw Audubon v. Los Angeles for many years.

RICHARD J. RIORDAN Mayor of Los Angeles, 1993-. Moved quickly to settle the Mono Basin controversy.

RICHARD ROOS - COLLINS Attorney, Natural Heritage Institute, San Francisco. In 1991, became lead attorney in the Mono efforts of California Trout.

ANTONIO ROSSMANN Attorney. From 1976, represented Inyo County in its dispute with Los Angeles; sought an Environmental Impact Report on Mono Basin diversions.

ISRAEL C. RUSSELL Geologist. In the 1880s, did the first major study of the Mono Basin.

DIAI D SHUFORD Ornithologist. Succeeded David Winkler as a leading gull researcher at Mono Lake.

NORMAN SHUMWAY Representative, Democrat of Stockton, 1979–90. Introduced the first bill for a Mono Lake National Monument.

LAURENS SILVER a Attorney. At the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund, pursued his own strategy on behalf of Mono Lake.

SCOTT STINE Geomorphologist. His findings about landscape evolution in the Mono Basin did much to shape the outcome of the battle.

TIM SUCH Legal researcher. Originated the public trust approach to "saving Mono Lake" and served on the Mono Lake Committee board for many years.

E. WOODY TRIHEY Stream restoration consultant. In charge of repair work on the Mono Basin streams 1990–93, he found himself in a philosophical and political crossfire.

MARK TWAIN Writer. On a visit in the late 1860s, he reported Mono Lake repulsive—but found it very good copy.

ELDEN H. VESTAL Fisheries biologist. In 1941, protested the diversion of Rush Creek. Fifty years later, his testimony was key to its restoration.

PETER VORSTER Hydrologist. Passing up a chance to work for the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, he instead became the hydrological guru of the opposition.

NORMAN S. WATERS Assemblyman,Democrat of Plymouth, 1977–90. Carried early Mono protection bills in Sacramento.

JAMES F. WICKSER Assistant general manager for water, Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, 1990-. Successor to Duane Georgeson, he sought to defend a crumbling position.

PETE WILSON U.S. Senator, Republican, 1985–90, then governor. In both roles he found occasions to support the preservation of Mono Lake.

DAVID W. WINKLR Ornithologist. Studied the California gull at Mono Lake and helped to launch the Mono Lake Committee.

ZEV YAROSLAVSKY LOS Angeles city councilman, 1975–94. First councilmember to advocate preservation of Mono Lake.

Prologue: The Bucket Walk

What in the world are these people doing? Is it a demonstration, a publicity stunt, some sort of exercise in sympathetic magic?

It's September 9, 1979, on the pale shore of a great lake at the eastern foot of the Sierra Nevada. A crowd of 250 people—longhairs and shorthairs, locals and visitors, biologists, birders, a noted photographer or two—has gathered. Every third person or so totes a banner or a sign, and everyone's carrying a container of some sort: a plastic jug or a plumped-out waterbag, a soft-drink bottle or a pail.

The odd group stands on an odd bright littoral, a seacoast far from the sea. Gulls come at a slant and cry. From the rippling surface rise curious white towers, built of a limy stone called tufa. Beyond them, dusky waterbirds dive and reappear, stuffing themselves with invertebrate fodder against migrations to come. A streak of high ground makes a path. At the end is a homemade sign: "Rehydrate here."

People clump together for the cameras, steadying the placards they carry: "Save Mono Lake!" " California Gulls Need Love, Too!" "Only God Has Water Rights!" Containers tip. Into a brine almost three times as salty as the sea (and getting saltier), fresh water falls, glittering.

"There," somebody says to the lake. "Have a drink."

The inland sea called Mono Lake can use it. It's been nearly half a century now since engineers of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power diverted most of the

Image not available.

Bucket Walk.

(Photo by Larry Ford)

creeks that feed this lake, forty-eight years since an artificial river began flowing south out of the Mono Basin toward a boomingcity 338 miles away. Without the normal inflow from these streams, the level of Mono Lake has been dropping a foot or so each year. Shrinking, the lake has grown saltier. Result: the slow impoverishment of a bizarre but prolific ecosystem, accelerating, there is reason to fear, toward collapse.

Today, by unconventional means, a little mountain water has made it down to the lake. Several hours ago and five miles away, on an aspen-shaded creekbank, these people dipped their containers into a living stream. Sloshing a little, they hiked down a glaciated canyon, past the city's diversion dam, through the village of Lee Vining, and out to this sunstruck shore. Now, pouring their pitiful quarts for the cameras, they make their point. They demand that the streams be allowed to run again—for real. They ask the city of Los Angeles to take less water from its dams and permit more flow to reach thelake—enough to let the salty surface rise, or at least stop sinking.

Why is it that they care?

"This solemn, silent, sailless sea," Mark Twain called Mono. "This loneliest tenant of the loneliest spot on earth." For most of a million years—and possibly for two or three—Mono Lake has lain in this basin at the eastern foot of the mountains, gaining water from streams and springs and glaciers and losing it to the air, forming its own

peculiar web of living things, becoming stranger and stranger. Twain caught the strangeness. He missed the richness, the colors, the beauty. Intrigued though he was, he could not forgive the lake for being salty, nor for being set in what all but botanists usually call a desert.

Others have made Twains mistake. We are trained to expect big lakes to have green surroundings, a cool northern look. That beer-commercial freshness isn't here, and it takes a while to appreciate what is. A quick drive past Mono Lake in the hot, bright middle of the day may well leave you wondering what all the fuss is about.

But if you hang around, be careful. In earliest morning, when the first light comes slanting in from Nevada; in midafternoon, when the sky grows lively with thunderheads; in the evening, when sunset colors the spikes and ramparts of tufa; toward the end of summer, when the lake is alive with a million migratory birds; in winter, when snow lies to waterline, you cannot stop and look without risk of being caught, of becoming what they call a Monophile.

The Bucket Walkers of 1979 were Monophiles. Buoyed by the company of the likeminded, they almost persuaded themselves that they might get their way. They indulged in the fantasy that Los Angeles would consent, rather soon, to give up the water they demanded. But to people who knew the odds and the politics—people who knew power—their effort seemed quixotic, doomed.

Between the Mono Lake advocates and their goal lay the weight of one of the most powerful bureaucracies in California. Even then the annual budget of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power was close to a billion dollars. Its rights to the Mono Basin water were seemingly absolute. It was not about to share that precious substance for the sake, as one writer put it, "of some tiny shrimp and a flock of birds."

Challenge the Department of Water and Power for even a small part of the aqueduct flow that keeps Los Angeles going? As well undertake to "rehydrate" Mono Lake with a canteen.

Yet this peculiar shore—wet where you'd look for dry, rich where you'd count on poor, wind-ripped, volcano-pocked, at the mile-high foot of a mile-high mountain wall, possessed of a beauty that is slow to penetrate but haunting once perceived—is a place where unusual things happen.

By the end of the 1980s, the battle over Mono Lake was to change the landscape of water law and policy in California. Called to umpire the controversy, one court would expand the ancient idea that major bodies of water are the people's property and that government has a special and inescapable duty to protect them. Another court would revive old, disregarded laws against the drying up of streams. Finally, in 1994, the state agency in charge of water rights would hand down a decision more favorable to the lake than any of the Bucket Walkers could have dreamed.

These events inevitably recall the legend of David and Goliath. But to leaders in the

Image not available.

Storm, south shore, 1979.

(Photo by Stephen Johnson)

Department of Water and Power, they must bring to mind instead the tale of Gulliver immobilized, unbelievably, by the thousand threads of the Lilliputians.

The Mono Lake controversy brings us back to the first but often flouted principle of conservation: "You may use, but you may not ruin." It reminds us, too, that this is a country in which determined citizens can take on mighty established powers and, occasionally, bring about real changes in the world.

Here is the place, and here is the story.

1—

The Place

In the middle distance there rests upon the desert plain what appears to be a wide sheet of burnished metal, so even and brilliant is its surface. It is Lake Mono. At times the waters reflect the mountains beyond with strange distinctness and impress one as being in some way peculiar, but usually their ripples gleam and flash in the sunlight like the waves of ordinary lakes. No one would think from a distant view that the water which seems so bright and enticing is in reality so dense and alkaline that it would quickly cause the death of a traveler who could find no other with which to quench his thirst.

Israel C. Russell, Quaternary History of the Mono Valley, California (1889)

Most people enter the mono basin from the south, from the direction of Los Angeles; or they come from the west, across the Sierra Nevada. Neither approach gives them much of a view. Better to get one's first look down into the basin from its northern gateway, from the minor pass called Conway Summit.

At Conway, finishing a long, gentle ascent, you arrive all at once at the rim of a great void. Your foot touches the brake; your gaze leaps outward and down. It is irresistible to see the lowland ahead just as geologists see it: a broken place, a sunken block, a graben.

If the first impression is of space, the second is of the mountains that contain it. To the west, rising directly out of lakewater, is the 7,000-foot eastern scarp of the Sierra Nevada, uncompromising, raw; its farther peaks curve left and seem to spread in front of you. Off east, the basin is bounded by lower ridges, Cowtrack Mountain and the wonderfully named Anchorite Hills; the eye runs beyond them to the prow of the White Mountains, highest of a hundred arid ranges out that way. South of the lake, not so conspicuous from Conway's height, lies the newest and strangest highland: the Mono Craters, symmetrical purplish piles of lava rock and volcanic ash, formed mostly within the last ten thousand years.

It's a hard-edged country, and it is a restless one. The Sierra, the White Mountains block, and the lesser ranges are rising now. The floor of the basin is dropping now. Lava is simmering deep underground and could force its way to the surface again at any time. This is a place where the planet changes fast.

Image not available.

Mono Basin aerial photo,

taken from the east,

1968.

(Photo by U.S. Air Force)

If there were no lake in the Mono Basin, the very shape of the country and the lively drama of the shaping would make this place remarkable. But there is a lake, a center, a Cyclops' eye in the great stony visage. You somehow never get used to its presence in the basin: so much water, carrying so much color of reflected sky and hill or glitter of bounced-back light, at this dried-out edge of California. One traveler recalls his first reaction: "What is that thing?"

Mono Lake is a roundish sheet of water, twelve miles across and, at the deepest points, about 150 feet deep. Don't note those figures in ink, though, for the lake is constantly changing its outline and dimensions, rising and falling from season to season, year to year, century to century. It fluctuates thus because it has no outlet. Water enters it chiefly from the Sierra side, from three big creeks—Mill, Lee Vining, and Rush—and leaves only by evaporation. Loss to the air varies with weather but probably runs somewhere between three and four feet a year. Streamflow varies much more: when the creeks gush, the lake rises; when they trickle, it falls.

High or low, the lake has been here a very long time. Mono has mirrored a stubbier

Image not available.

The inner line is the outline of the lake, with a surface elevation near 6,376 feet

above sea level, reached several times after 1977. The outer line is the lake as

it stood in 1940, at surface elevation 6,417 feet. Between them is the lake at

6,390, a level last seen in 1970—and the level to which the lake will now be

allowed to rise once more.

Sierra and seen the Mono Craters rise from the plain. Flows of lava have hardened in it; tongues of glacier ice have melted on its shores. Pumice boulders and icebergs have floated on it. Volcanic ash and cinders have rained into it and left datable layers, like tree rings, in its bed. This body of water is literally older than the hills—the newer hills, anyway. Somehow, it looks it.

The Making of Mono

To have so durable a saline lake you need a natural basin and just the right amount of incoming water. Too little precipitation and runoff, and your lake dries up; too much, and the water level rises to find an exit from even the deepest hole. The geology of the American intermountain West has produced hundreds of closed basins; it has also produced a climate too arid, by and large, to put permanent lakes in them.

The relevant part of the geologic story begins three or four million years ago. The Sierra Nevada was already fairly lofty then, but the land immediately east of it was utterly different from what we see today. Instead of dropping away to desert and steppe, the country continued high. The Sierra merged with a high plateau. Rivers drained west across this cool plain; one major stream flowed out of today's Nevada, across the present site of Mono Lake, and on westward to the sea.

But changes were approaching from the east. In a vast area of what is now Nevada, the crust of the earth was fracturing on parallel north-south lines. Between these faults, huge blocks lurched and tilted, forming new mountains and new valleys. As time passed, this splintered area expanded both east and west. We call it the Great Basin. When Great Basin faulting reached California, slices of terrain split off from the rising Sierra block, leaving today's precipitous eastern scarp.

What caused this revolution in the landscape? It signals nothing less, geologists now believe, than the secession of a continent. The western United States is in the process of rifting, calving off a new Pacific land mass, a California island. The faults found here are of the type that form when a region is stretching, pulling apart. Some one of these fractures, millions of years hence, may widen into a narrow sea connected with the ocean, like today's Red Sea. The fracture might occur along the Sierra's eastern foot—right here.

As the terrain grew more dramatic, the climate too became more extreme. For the shattered lands east of the Sierra Nevada, that mountain chain became a fence against rain. Storms off the Pacific dumped their moisture on the western slopes of the range; few peaks to the east rose high enough to wring much precipitation from the depleted clouds. Faulting and lava flows cut off the flows of old rivers too feeble to maintain their courses across the changing surface. Just over three million years ago, the river that had flowed across the Mono region became a casualty. The westward reach of the stream became a short river on the western slope, the Middle Fork of the San Joaquin.

Image not available.

Mono Lake lies at the western edge of the Great Basin, a vast region of parallel mountain ranges

and valleys, most of which drain to salt lakes or desiccated playas.

Ancient Mono

By three million years ago the Mono Basin seems to have become an isolated bowl, a likely place for standing water. Indeed, fish fossils suggest that a lake formed here very early; they show, moreover, that it was fresh and had an outlet to the north. It is possible, though not proven, that the original lake has persisted, changing but never entirely drying up, from that day to this.

If scientists can't document three million years' worth of lake in the Mono Basin, they are pretty sure, thanks to a datable volcanic spasm, about the last three-quarters

of a million. Not far away, about 760,000 years ago a great boil of lava swelled and burst, leaving a pit, a caldera; that cavity forms the next basin south of Mono along the Sierra escarpment and is called Long Valley. The Long Valley eruption was 2,500 times the size of the 1980 blast that decapitated Mount St. Helens; it dropped ash as far east as Missouri and a thick layer of it, known as the Bishop Tuff, over 450 square miles of local terrain. If you drill a deep enough hole in the bed of Mono Lake, you encounter what appears to be the tuff, with younger lakebed sediments above it—and older ones below.

Most of the terminal lakes in the Great Basin have dried up now and again since the time of the Long Valley eruption. That Mono Lake has not is due to its favorable site: high and cool (reducing evaporation) and tucked in right under the snowy Sierra Nevada. Nearby, moreover, is a weather gap, a door for storms. West of Long Valley, the Sierra crest sags like an ill-pitched tent; several passes are as low as 9,000 feet. This low region is not accidental but marks the general path of the ancestral San Joaquin; one of several saddles here, Deadman Pass, nearly coincides with the notch last occupied by the vanished river. Storms off the Pacific funnel up the broad valley of what is now the Middle Fork, slip over the low crest, and have water left to dump on the east side. Heavy winter snowfall sustains one of the nation's largest downhill ski resorts, at the town of Mammoth Lakes. It also supports a surprising forest on the heights just south of MonoLake: the world's most extensive stand of the handsome, plate-barked Jeffrey pine. And the same high precipitation swells Rush Creek, the lake's most voluminous inflowing stream.

Ice and Fire

As far as we know, Mono Lake has never sunk much lower than in recent times, but it has certainly risen very much higher. As recently as 120,000 years ago, it mounted far enough to find an outlet from its basin—to the east and south, that time, into the Owens Valley.

About 36,000 years ago, as ice began to gather in Sierra canyons, the lake again grew large, but it did not overspill. During the heart of the most recent glacial period, from 20,000 to 15,000 years ago, the present site of Lee Vining was a shoreline, and Lee Vining Creek was laying down the delta on which the town now sits. About 12,500 years ago, the lake mounted still higher; you can see its highest shoreline etched onto the slopes, hundreds of feet above the rooflines and satellite dishes.

Sometimes in winter a dense fog forms over Mono Lake. The Paiutes called it poconip . In Lee Vining it obliterates the sun for days and gives every branch and twig a cold fur of rime. From the sunny surrounding heights, the fog layer mimics a higher lake: what the basin looked like in glacial times is not hard to imagine.

The approximate scope of the glacial lake can also be judged by Black Point, a

Image not available.

Fissures on Black Point, formed when lava cooled under the

waters of ancient Mono Lake (Lake Russell).

(Photo © Jim Stimson)

Image not available.

Mono Lake during the Tioga Glaciation, as mapped by pioneer

geologist Israel Russell. During this last major glacial period,

advancing ice and rising lakewater reached the same elevation

line, but they reached it at different times: when the lake attained

its high point, about 13,000 years ago, the glaciers had already

shrunk well back. If "Lake Russell" had climbed another 120 feet,

it would have found an outlet from the Mono Basin at a saddle to

the east (arrow). The Mono Craters, which were differently

configured at the time, are incorrectly shown.

Image not available.

During the last glacial period, lakes covered

much of the Great Basin: sprawling Lake

Lahontan to the northwest, vast Lake

Bonneville to the northeast, and lesser lakes

and rivers by the score. But now water is

scarce in the region, and the remaining lakes

are precious.

broad-shouldered, gentle mass of basaltic cinders on Mono's north shore. This volcano erupted underwater about 13,300 years ago. Cooling quickly, the lava that formed the core of the cinder cone cracked, forming crevasse-like fissures. The very top of the mass seems to have reached the lake surface, where waves beveled it off, giving it an almost dead-flat summit. Black Point is said to be the only volcano in the world that formed underwater and is now completely exposed.

By 9,000 years ago, at the latest, Mono had shrunk to something like its present

outlines. (Technically, only after this subsidence is it called Mono Lake: in all earlier incarnations it is known as Lake Russell, in honor of nineteenth-century geologist Israel Russell, the pioneering researcher there.) The shrunken Mono kept fluctuating, within a range of about 130 vertical feet. Its upward "transgressions" and downward "regressions" appear to correspond to century-scale sunspot cycles (which in turn reflect variations in the energy output of the sun).

Volcanic activity continued, adding numerous new summits to the Mono Craters. The pace of this mountain-building seems to have picked up in the last 3,000 years. Panum Crater on the south shore of the lake, a young and perfect example of a plugdome volcano, built itself in the fourteenth century A.D. Its peak of rhyolite obsidian rises within a ring of light pumice gravel. To get a visual grasp of the Mono Basin, you can't do better than to walk the Forest Service trail around this crater.

The present lake islands are volcanoes, too. The smaller, darker island, Negit, is made up of many flows of blocky lava, mostly formed between 1,700 and 300 years ago. Java islet, one of the specks of land near Negit, was raised about A.D. 300, when the lake was very low; the Java eruption spat out tens of thousands of blocks of pumice that floated across the lake, grounded on its shores, and rest there, tufa-encrusted, today. Paoha, the large "white island," emerged sometime in the seventeenth century. Then the rising lava did not reach the surface but burrowed into the lake-bottom sediments, pushing them upward; the powdery surface found on most of Paoha is simply the lake bottom, high and dry. Sediment slid off the island's flanks to the west as it rose and produced shoals that sometimes break the surface of the water as the Paoha islets.

A Grain of Salt

Terminal lakes always turn salty in time. Inlet streams bring in salts and other minerals dissolved from the rock of their watersheds; evaporation removes only pure water. The other compounds stay behind. It is estimated that 285 million tons of chemicals are now dissolved in Mono Lake. How concentrated the solution is, by the gallon, depends on how much water is diluting that load. Before Los Angeles began diverting its feeder streams, Mono Lake was about a third again as salty as the sea; in 1981, it was three times as salty as ocean water.

You can make Mono Lake brine, more or less. Take a gallon of pure water. Add ten tablespoons of table salt. Add eighteen tablespoons of baking soda. Add eight teaspoons of epsom salts. Add a pinch or so of laundry detergent and borax, and you've about got it. Taste it, and you'll feel no urge to swallow.

Chemically, Mono is known as a triple-water lake: it is saline; it is alkaline; and, due to its volcanic surroundings, it is sulfurous. Fluoride, boron, and arsenic levels are also extremely high, and there are surprising amounts of uranium, thorium, and plutonium. Salt lakes are known for peculiar chemistries, but even among them Mono is outstand-

ingly bizarre. Some scientists speculate that the oceans of the pre-Cambrian era, half a billion years ago, may have contained a fluid similar to Mono Lake water.

"The waters are clear and very heavy," wrote William Brewer, an early visitor. "When still, it looks like oil, it is so thick, and it is not easily disturbed. The water feels slippery to the touch and will wash grease from the hands, even when cold, more readily than common hot water and soap. I washed some woolens in it, and it was easier and quicker than any 'suds' I ever saw. . . . I took a bath in the lake; one swims very easily in the heavy water, but it feels slippery on the skin and smarts in the eyes."

This "heavy water," very reflective, makes Mono an outstanding mirror of its surrounding mountains. When wind works the water up into waves, the lake foams more readily and more lastingly than the ocean.

The Living Sea

All salt lakes get compared to the Dead Sea, that hypersaline sink of the Jordan River in Palestine. The Dead Sea, where the chemical mix is so strong as to preclude all life except bacteria and protozoans, deserves its name, but the typical salt lake does not. Certainly Mono doesn't. In the spring and summer it explodes with life, growing algae and other microscopic plants by the millions of tons. On the algae feed two simple, prolific organisms: a specially adapted, tiny crustacean, the brine shrimp, Artemia monica ; and a specially adapted, tiny insect, the alkali fly, Ephydra hians . The shrimp can be found throughout the lake, in the oxygen-rich upper level of water; the flies, related to houseflies but without their annoying habits, make a band around its entire shoreline.

The Mono brine shrimp is unique to this lake. The creatures are about half an inch long, translucent, tinged many colors but most often red. Oarlike appendages, eleven on each side, scull the water and sweep algae particles to the mouth. The shrimp hatch out in the spring from cysts in the bottom muds and go through several stages of maturation. A second generation is born live during early summer. With cool weather the animals die off, having sent another shower of dormant, partially developed, encysted embryos to the lake floor. Shrimp in the lake, at their annual peak, typically number seven trillion .

Alkali flies hatch from eggs laid underwater in algae mats. The larvae live on submerged rocks (the pumice blocks from Java islet are ideal for them) or on drowned vegetation, pulling themselves along with clinging "prolegs" and grazing. After two or three months of growth and three molts, they clamp themselves down and pupate, emerging in one to three weeks as adults. Several generations hatch each year, and flies are present even in winter. These vegetarian insects aren't pests or scavengers; indeed, it is hard to touch one. Whenever feet approach the shoreline, the flies retreat, a humming cloud. You can herd them into swirls with your hands.

Image not available.

LIFE CYCLE of the BRINE SHRIMP

In the spring, miniature shrimp called nauplii hatch from egg-like cysts and mature in about two months. In early summer, the cyst-hatched shrimp produce a second, live- born generation. Before dying in the fall, the shrimp release the next year's cysts, which sink to the bottom muds. Artemia monica is the only brineshrimp species whose cysts sink rather than float.

LIFE CYCLE of the ALKALI FLY

Females crawl under water to lay eggs, which hatch into aquatic larvae. After feeding on algae for a month or more, the larvae secure themselves to tufa or drowned vegetation, pupate, and emerge one to three weeks later as winged adults.

Image not available.

Brine shrimp and alkali fly life cycles.

(Adapted from drawings made by

Joyce Jonté for the Mono Lake

Guidebook.)

The Birds

Millions of flies, trillions of shrimp: food by the ton for something or someone. But who'll play top-of-the-food-chain? The lake is not just too salty for fish; it is also too salty for the liking of most water birds. So the harvest is left to a few bird species adapted to fill this peculiar habitat niche.

The bird you can't miss in the summer, anywhere in the basin, is Larus californicus , the raucous California gull. Unlike most of the twenty-five North American species known as "seagulls," this species leaves the coast in summer for breeding sites far inland. The largest breeding population is at Great Salt Lake, the second largest at Mono.

Image not available.

The food chain at Mono Lake is short and

simple. Brine shrimp and alkali flies eat algae.

Birds eat shrimp and flies (the latter are

scarcer but nutritionally superior). Nitrogen

and other nutrients return to the algae by

way of excretions and decay. Available

nitrogen appears to be the main limit on

productivity. High salinity makes algae less

efficient at "fixing" nitrogen from the air and

slows the whole system down.

(Adapted from a drawing made by Rebecca

Shearin for the Mono Lake Guidebook.)

The Mono gulls nest on various islets, almost invisible from the shore, and on the prominent "black island," Negit, when it is available. But when the lake is low enough, first Negit and then the larger of the islets fuse to the shore, and coyotes prey on eggs and young, soon driving away the birds.

The gulls range far from the lake. One of them once scooped a trout out of a tarn near Koip Peak Pass, far up among the Sierra summits, and lost it onto the grass at my unlicensed feet. I had fish for dinner anyway. Gulls also haunt garbage dumps and

Image not available.

Bird Migrations.

(Birds drawn by Joyce Jonté.)

scavenge on the streets of Lee Vining. "Rats of the air," somebody called them. But the landmark Ecological Study of 1977 has it right: "In winter, when the gulls have returned to the oceans where most of their congeners breed, the inland sea at Mono seems barren without them."

The eared grebe, Podiceps nigricollis , might be the totem creature of Mono. It is a small, dark bird with patches of gold on each side of the head (the "ears"). Grebes are specialists. They dive superbly, fly unremarkably, and barely walk at all. They feed, sleep, court, and mate on water. Though grebes don't breed at Mono Lake, up to a million birds stop off here in summer and fall. They arrive scrawny, with worn and damaged feathers; here, floating safely well out on the lake, they molt and feed, and feed, and feed. At its peak, the throng consumes brine shrimp at the rate of sixty tons a day. When cool weather comes and the shrimp supply crashes, the grebes move on to the Salton Sea and the Gulf of California, 350 miles to the south. The overfattened birds must work off some of their weight in futile takeoff attempts before they can actually get into the air.

Phalaropes are delicate, diminutive sandpipers. They have sharp, straight beaks and black-and-white markings touched with brownish red. The females are larger, more brightly colored, and dominant. There are just three species of phalaropes in the world; Mono Lake is important to two of them.

The northern or red-necked phalarope, Phalaropus lobatus , breeds in the far north and winters at sea, on the open subtropical oceans. Mono and Great Salt Lake are major stopover points in between. Red-necked phalaropes at Mono eat, almost exclusively, alkali fly larvae, pupae, and adults. They feed on the open water.

Then there is the Wilson's phalarope, Phalaropus tricolor . Of all these birds it is the Tuesday's child, the one with far to go. After breeding in a widespread North American range, up to 60,000 birds—perhaps 10 percent of the adult world population—converge on Mono Lake. Like grebes, they arrive worn and depleted, molt and regrow their pelages, and rebuild their fat reserves with flies and shrimp. You sometimes see the birds charging through the lakeside cloud of flies, beaks wide open, swallowing as fast as they can. (Gulls feed in the same manner.) The phalaropes double their weight during an average five-week stay and waddle back into the air.

They need every calorie for the second, longer, nonstop leg of their journey: 3,000 miles, largely over the open Pacific, to winter quarters at saline lakes in Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina. Returning to North America in the spring, they fly in more moderate stages, east of the Andes and the Rockies.

Another very noticeable migrant is the American avocet, Recurvirostra americana . This large, long-legged, long-billed wader has been called "the most graceful of all shorebirds." It has black-and-white markings and, in summer, a cinnamon-colored head and neck. Several thousand avocets stop off at Mono in the spring (northbound) and summer (southbound); a few nest on Paoha Island.

Because Mono Lake lies in a region of scanty aquatic habitat, the arid Great Basin, its importance to these migratory birds is magnified. The lake is one of the three or four most significant shorebird habitats in the western United States; it is internationally recognized as a unit in the Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network.

Another notable bird at Mono Lake is one you need luck, and probably a birder's telescope, to see. The snowy plover, Charadrius alexandrinus , is a bulbous sort of shorebird, white-bellied and brown-backed, that nests on dunes and alkali flats on the lake's east side. Mono Lake's population of several hundred birds is one of the largest in the state. Plovers primarily eat alkali fly larvae and adults and a couple of kinds of beetles.

Still other species, rare today at the lake, used to be as numerous as grebes and as ubiquitous in their season as gulls: the various types of ducks. Before Los Angeles took the creeks, a long-time local resident remembers, "There were so many ducks along the shore sometimes that when they'd move out all together [it was] like the shore itself was moving out." As late as the 1940s, the lake was a fine place for migrating northern shovelers, mallards, green-winged teals, redheads, and numerous other duck species—and a correspondingly popular place with hunters. At times in the fall a million birds would use the region, feeding on the flies and shrimp as well as on land insects and vegetation. Mono water was too salty for them even then, and the lake too choppy when the wind blew, so they gathered in sheltered spots where the surface layer of water was fresher: near creek mouths, in coves, and on the brackish lagoons that bordered the northeast shore of the lake. When those habitats disappeared, so did the great flocks, though there are still a few thousand ducks at Mono Lake today.

The Tufa Towers

After years of calendars and magazine photographs, to say "Mono Lake" is to call up an image of pale stone monuments: the fabulous tufa towers.

The same chemical composition that makes Mono Lake a fishless filling station for birds produces these features. Tufa consists of several forms of calcium carbonate, or lime. The lakewater is full of carbonate ions; fresh water draining into it contains lots of free calcium to combine with them. Wherever the waters mix, the constituents precipitate out as stone. When runoff is vigorous, the mixing can occur almost anywhere; at times a sheet of fresh water spreads across the entire lake, and wave action is enough to cause tufa to form. Every stationary object on the shores of Mono Lake eventually gets coated with the stuff.

But tufa takes the dramatic tower shape only where freshwater springs issue under the lake. Lime precipitates on contact. The fresh water, lighter than the salt, keeps rising, producing a growing sponge of stone. Other processes give this porous trunk a solid rind. Algae that grow on its outer surface alter the chemistry of the nearby water, causing a harder form of tufa to precipitate around them. Even alkali flies get into the act: as

larvae, they have special "lime glands" that filter calcium carbonate from their blood; when the adults emerge, little globules of lime are left behind. Generations of larvae, grazing on existing tufa, thicken it as they pass.

You can walk dryshod among tufa towers, whole groves of them left high and dry by the receding lake, but the towers you see so readily are dead. They no longer grow; with few exceptions, they no longer contain their springs. They are like sapless snags that will eventually crumble in the air.

To see tufa towers alive, you must take to the water. Skimming along in a canoe, you'll see pale shapes growing toward the surface, some of them sending up fresh water in greater or lesser plumes. Above these spots brine shrimp swarm most densely. Where a tower just reaches the surface, it may bubble like a drinking fountain.

Divers get the best view of tufa. Biologist David Herbst reports "columns of tufa that on land could not support their [own] weight . . . often covered with veils of bluishgreen algae and sparkling crystals of the mineral gaylussite" (an evanescent tufa form). Canoe guide Gary Nelson says, "Beneath the lake, tufa are as close as rocks can get to being living organisms. The rocks are covered by a light green patina of algae, speckled with dark clumps of alkali fly pupae, and are literally crawling with adult flies encased in tiny bubbles of air."

Tufa occurs at saline lakes around the world, but nowhere, apparently, in this abundance or in this range of shapes—all these pinnacles, ramparts, mushrooms, knobs, and domes. Mono Lake tufas rise from the water, strange archipelagos doubled by reflection. They lean on upland slopes like menhirs, casting the only shade for miles. In this tree-poor landscape they serve the same functions as snags. Falcons and owls and small mammals nest in them. They also draw photographers, who may seem, at dawn and dusk, the most numerous creatures of all.

2—

Before Los Angeles

But men have known The secret a long time. Men, forgotten, Few . . . Knew in the old time the standing before us of Strangeness under the clear air.

Archibald MacLeish, The Hamlet of A. MacLeish

One may still read that mono is an Indian word for "beautiful." This is pure European sentimentality. Mono is a Yokuts Indian word for "fly." The Yokuts did not live here, but they traded with the tribe that did, a subgroup of Paiutes known to themselves as the Kuzedika, the Fly Larvae Eaters. What the Kuzedika called Mono Lake itself their descendants do not remember.

The Kuzedika, like all their Paiute kin, were expert hunters and gatherers. Like other groups, they harvested nuts from pinyons and edible moth larvae from Jeffrey pines. Like their relations, they hunted rabbits, pronghorn antelope, and other game. They caught gulls and grebes when they could, and harvested gull eggs. They ate roots and seeds and berries. But they named themselves for their distinctive food source and stock in trade: the pupae of the alkali fly, the kutsavi .

When an alkali fly larva is ready to pupate, it clamps itself onto a hard surface by its prolegs and grows still. Its soft outer layer becomes a hard husk, a puparium, within which the creature transforms itself into an adult. Some pupae get dislodged by wave action, float to the surface, and drift to shore. This drift used to be much heavier than now. The Kuzedika sieved it from the water in finely woven baskets and spread it to dry. Early observer Israel Russell described the next step: "The partially dried larvae [sic ], the kernels, are separated from the inclosing cases, the chaff, by winnowing in the wind with the aid of a scoop-shaped basket; they are then tossed into large conical baskets, which the women carry on their backs." Traveler William Brewer recorded: "The worms [sic ] are dried in the sun, the shell rubbed off, when a yellowish kernel

Image not available.

John Muir with Kuzedika Paiutes.

(Photo courtesy the Bancroft

Library)

remains, like a small grain of rice. This is oily, very nutritious, and not unpleasant to the taste." Kuzedika families had harvest rights to certain strips of shore, larger or smaller depending on their status, and were known to do battle over them.

The Kuzedika had no fixed settlements but followed the food sources. In the spring and early summer they lived on the west side of the lake, along Rush Creek, Lee Vining Creek, and Mill Creek. In late summer they moved to the lakeshore for the kutsavi harvest. In the fall they shifted to the pine woods. In the winter they moved away from the gigantic shadow of the Sierra to sunnier, less snowy lands east or north of the lake, living largely on pinyon nuts from the adjacent wooded hills. In a bad year, when the pine nut crop was low, they might trek east or south to Paiute relatives, or even west to the Miwoks of Yosemite.

For in fact the Kuzedika lived at one end of a highway of the day, a major trade route between the east-side Indian groups and the rest of California. This transalpine path went up Walker Creek, a tributary of Rush Creek, to Mono Pass and on down the western slope to Yosemite Valley and beyond. West along it trade parties carried kutsavi , dried caterpillars, pine nuts, salt, paints (red and white), pumice, rabbit-skin blankets, sinew-backed bows, and arrows tipped with obsidian. East came acorns, manzanita berries, paints (black and yellow), shell beads, and bear skins. Differing styles of baskets went both ways.

The Kuzedika were artists of basketry, bending local willow bark, fern fronds, grass roots, and rose stems into elaborate patterns. (Travelers in the eastern Sierra should not miss the Kuzedika baskets in the Bridgeport Museum, each different, each made without model or pattern. Most striking is the late beaded work, combining traditional skills and manufactured beads in a product that was made only for a short while.)

The Kuzedika life was competent and hard. It seems not to have changed, in the

Mono Basin, for a very long time. Not far to the south, in the Owens Valley, another group of Paiutes had apparently instituted regular irrigation. But the Mono Basin, a higher and harsher landscape, was perhaps an unlikely site for such an innovation.

Invasion

In 1833 the explorer Joseph Reddeford Walker trekked east to west across the Great Basin. On its way to "discovering" Yosemite Valley (probably) and the giant sequoias (certainly), the party visited an alkali lake. It is tempting to identify that lake as Mono; historians doubt it, however. The indisputable American entry into the region came remarkably late, in 1852. In June, Lieutenant Tredwell Moore of the U.S. Army went into the Sierra after Miwok Indians who had reportedly attacked prospectors on the Merced River. Following the Indian trade trail through the high country, he learned that Chief Teneiya, the object of his pursuit, had moved on ahead of him, into the Mono Basin. Sometime that summer—the exact date is not known—Moore crossed Mono Pass and descended the abrupt east flank of the Sierra to the Mono Basin floor. The party found no Chief Teneiya; they had some friendly Contact with the Kuzedika, gave the lake its modern name, and sampled some gravels that seemed to promise gold.

In August the Stockton Journal told the story. By fall, one Leroy Vining, after whom the town of Lee Vining was later named, was prospecting in the basin. He had no luck and switched to logging, but other miners struck it rich. A series of gold and silver rushes brought to the basin populations much larger than today's.

Most of the action was north of the lake, in the gaunt Bodie Hills that spread east from Conway Summit. The first boom was in 1857 at Dogtown, on the north slope of those hills, just outside the Mono Lake drainage. The second, in 1859, was nearer the lake at a place called Monoville or Mono Diggings, the first proper town east of the Sierra crest and south of Lake Tahoe. Local streams had too little water to wash the gravels, so ditches were dug to tap Virginia Creek on the north side of the hills—a diversion into the Mono Basin that continues to this day. Then the miners' attention shifted to Bodie, near the crest of the little range in a chilly and windswept bowl. The fourth boom was in silver and produced Aurora, farther east along the range. After a few quiet years, the excitement returned to Bodie and outdid itself. During the early 1880s Bodie was the hub of the region. It was also infamous for gunfights, murders, and prostitution. An apocryphal story has a little girl in Truckee saying in her prayers, "Goodbye, God, I'm going to Bodie."

With Bodie booming, any number of satellite mining districts opened up, especially on the Sierra side of the lake. There were little towns, ambitious while they lasted, up Mill Creek (Lundy Canyon) and near the headwaters of Lee Vining Creek.

At its height, Bodie had a population of well over 5,000. A local agriculture grew up to sustain it. So did a local lumber industry. In 1879 a five-ton steamer was hauled from

Image not available.

The ghost town of Bodie, onetime economic

capital of the Mono Basin.

(Photo by Gerda S. Mathan)

San Francisco to the lake to tow lumber barges across from Lee Vining Canyon. The next year Bodie interests constructed a narrow-gauge railroad around the east side to reach the vast Jeffrey pine forest on the south shore. Extensions were planned to link this local line with other western railroads, but they never materialized.

The birds, too, helped sustain the mining towns. The red-necked phalaropes, known as "Mono Lake pigeons," were hunted for the pot. Egging expeditions went out to Negit and in a few years greatly reduced what had been a large gull population, if contemporary impressions can be trusted. In 1860, gull eggs sold for seventy-five cents a dozen.

As for the lack of fish, the settlers quickly rectified that. Freight wagons with water barrels carried Lahontan cutthroat trout up and down the region, stocking streams. After 1900, hatchery-raised trout of several species were planted; the German brown trout naturalized best and came to dominate in most local waters.

The boom at Bodie was a brief one, but the town flickered on. In 1917 the logging camp at Mono Mills was abandoned, and with it the railroad. In 1932 a fire put a final stop to operations in Bodie itself.

Today, the sites of Dogtown, Aurora, Mono Mills, and Lundy are identified only by historical markers. Monoville is a scatter of scars and foundations; you need a local guide to find it. At Bodie, about one-twentieth of the buildings survive, preserved in Bodie State Historic Park, perhaps the most visited ghost town in the world. In a mod-

Image not available.

For fifty years after 1859, mining was the key

activity in the Mono Basin. (Adapted from a

map created by Thomas C. Fletcher for

Paiute, Prospector, Pioneer.)

ern twist, preservationists have recently worked to prevent further and presumably less picturesque mining in the region around Bodie.

Early Reactions

From the beginning, everybody who saw Mono Lake had an opinion about it. Some marveled, some recoiled.

Alexis Waldemar Von Schmidt, who came to the basin in 1855 to do the first land

survey, called the scene "the most beautiful I ever saw." Mark Twain was here in 1861–62 and said it was "little graced with the picturesque." Judging by his descriptions in Roughing It , Twain found the region fascinating nonetheless. Like others, he noticed that the water was a good detergent, but he had a sharper eye than some for the life it supported: "millions of wild ducks and sea-gulls," and in the lake itself "a white feathery sort of worm, one half an inch long, which looks like a bit of white thread frayed out at the sides. If you dip up a gallon of water, you will get about fifteen thousand of these." He noticed the alkali flies, too, and the way they could walk under water, holding bubbles of air beneath their wings. He ate his fill of gull eggs and went out to Paoha Island to look for a hot spring that people said would cook an egg in four minutes. On the way back, a sudden afternoon windstorm swamped his boat. The same thing has happened to many on this lake, and not a few have drowned.

William Brewer, whose journal Up and Down California is a priceless source on the primitive state of the state, came over Mono Pass in 1863. "It is a bold man who first took a horse up there," he wrote of the steep eastern path. "The horses were so cut by sharp rocks that they named it 'Bloody Canyon,' and it has held the name—and it is appropriate—part of the way the rocks in the trail are literally sprinkled with the blood from the animals." As for Mono Lake itself, Brewer was of Twains persuasion: he found it not quite pleasant but entirely intriguing.

In 1865, journalist J. Ross Browne came for Harper's . He admired most of what he saw: the mountain shapes reflected on the water; the tufa towers, especially when they resembled classical architecture; the clear air; the flocks of ducks. But he thought the rim of kutsavi rather disgusting.

John Muir tramped over the old Indian trail not long after. He loved the country in general for its mix of glacial and volcanic landscapes, "frost and fire." In his account of the trek he says much about this setting, rather little of the lake itself. Perhaps, like many first-time visitors, he didn't know what to make of this uncommon piece of water. On a second visit, he went to Paoha Island in "an old waterlogged boat," got into windstorm trouble, and seems to have warmed to the place.

Then came Israel Russell. The young geologist arrived in the region in 1881, when the Bodie railroad was under construction, and he stayed for several years. He seems to have been the first to set aside alpine standards of scenery to admire Mono Lake as the desert phenomenon it is. He clearly saw it as strange—"a sea whose flowerless shores seem scarcely to belong to the habitable earth"—but he was captured by the beauty in the strangeness. His 1884 monograph, Quaternary History of Mono Valley, California , is well worth reading today.

Russell described journeys throughout the basin and up and down the ranges, made shrewd guesses about the geology, and puzzled out much of the natural history of tufa. He gave their modern names to the Mono Craters and Negit and Paoha islands, using

Paiute words though not the original Kuzedika names (now lost). Paoha refers to water spirits—dangerous ones, though Russell seems not to have known that. Russell thought Negit meant "blue-winged goose." This is uncertain, but, logical though it might seem, Negit does not mean "gull."

In 1890, when Congress was debating the bill to establish Yosemite National Park in the mountains to the west, Robert Underwood Johnson of Century magazine called for a preserve extending "to the Nevada line." (Johnson was a friend of John Muir's, and the plan may really have been Muir's as well.) The indicated boundary would have taken in about the southern third of Mono Lake. As first enacted, the park did at least include the upper reaches of all the important Mono Lake feeder streams. The presence of parkland in the Mono watershed might, perhaps, have drawn earlier attention to the fate of the lake below. But in 1905 the park was shrunk back to the Sierra crest. Yosemite and Mono, two of California's most debatable landscapes, would henceforth be fought over quite separately.

Life after Bodie

As mining petered out, the Mono region needed a new basic industry. Three possibilities offered: oil, tourism, and irrigated agriculture on a new and grander scale.

It's hard to believe it now, but there was a brief, roaring oil boom in the Mono Basin. Sediments have been accumulating on the lakebed so long that old plant matter has indeed been transformed into small amounts of primitive petrochemicals. Wells were drilled on Paoha Island and on the north shore. There was talk of a city of 20,000 on the western shore. But the wells yielded mostly hot water (and geological information).

As roads improved, a trip to the Mono Basin became something less than an expedition, and a tourist trade evolved. In 1915, the transmountain road over the Tioga Pass began to carry traffic from the crest down the canyon of Lee Vining Creek to the basin floor. The rancher who owned the land where the new road met what is now U.S. 395, the highway along the eastern base of the Sierra, saw his chance. Laying out a town at the junction, he named it after pioneer logger Leroy Vining. The speculation took, and Lee Vining became the commercial crossroads of the little region.

The largest town, however, took shape in a curious nook in the Sierra front, invisible from U.S. 395. Just southwest of Mono Lake, an isolated mountain stands out from the main mass of the range. When the glaciers advanced, they split around it, an inverted Y of ice. Rush Creek flows down the stem and north branch of the Y. In the south branch, dammed by the old moraine, is June Lake. Today its outlet stream runs backward, into the mountains, to join Rush Creek. The town of June Lake, which grew up in the 1920s, was to become the local base for Sierra recreation, with skiing in nearby resorts, fishing in nearby lakes and streams, and hiking in nearby wilderness areas.

It would be said, later on, that local people made little of their other potential tourist draw, Mono Lake itself. This is false. The lake at the time was only half again as salty as

Image not available.

Lee Vining.

(Photo by Jim Stroup)

the sea and fairly swimmable; it also had plenty of beaches. And it was the only sizable recreational lake in a vast region. One local family, the McPhersons, made a project of putting these attractions on the map. After their plans for a lavish health resort on Paoha Island fell through, at the northwest corner of the lake the McPhersons opened the Mono Inn, a landmark ever since. You could stay at the Mono Inn for $2.50 a night, go hiking, fishing, swimming, or skiing, buy evaporated lake salts to cure whatever ailed you, and visit the islands daily, or on a moonlit night, on board the forty-two-passenger cabin cruiser Venita .

In 1928, Venita McPherson organized the first Mark Twain Day. The name was something of a joke, for the purpose of the event was to prove that the writer who had called the region "a hideous desert" was wrong. Twain Day was held, of course, at the inn. There were speeches, skits featuring Twain characters, races on land and lake (including one for motorboats and one for swimming horses), a bathing beauty parade, and dance tunes by the Bridgeport Orchestra. Twain Day (later Days) became an August tradition and lasted until World War II. After a hiatus, they were started up again in 1968.

Dams and Ditches

By 1910, hydroelectric dams and powerhouses began to go up on the major Mono Basin streams. Various interlocking power companies arose and were absorbed, in time, by Southern Sierras Power, which in turn gave place to Southern California Edison. Mono Basin energy, like its water, was to flow south.

Hoping for a railroad connection to markets in the outside world, local promoters

were meanwhile planning to apply the creeks to large-scale Mono Basin agriculture. The loudest talk came from the Rush Creek Mutual Ditch Company: it proposed to send water from Rush Creek clear around Mono Lake to irrigate the fertile but arid lands on the southern, eastern, and northern sides. The ditch was begun—the steam shovel that built it stands today in front of the Mono Basin Museum in Lee Vining—and made it as far as the Mono Craters. But when the unlined channel was tested, the water sank into its porous bed and vanished.

The Mutual Ditch Company's more successful competitor, the Cain Irrigation District, was part of the hydropower combine. In 1915, the Cain District built a small dam at an inviting site on Rush Creek where the stream breached one of the recessional moraines of the last glacier. The resulting reservoir, called Grant Lake, submerged a natural pond of the same name. In 1925, the Grant Lake dam was raised. Large areas on either side of Rush Creek, in what is called Pumice Valley, were brought under irrigation. Much of the water sank into the ground and fed springs along lower Rush Creek and in the bed of Mono Lake itself. Researcher Scott Stine believes that the tufa towers at the southern arc of the lake, at the spot called simply South Tufa, date from this period.

As time went on, all this activity began to seem rather pointless. Even in the 1910s it was rumored that the waters of the Mono Basin would be called on for export south. In the 1920s the rumor became a certainty. As they lavished water on the leaky fields of Pumice Valley, the local irrigators were not so much raising a crop as making a point about their water rights. They were boosting the value of a commodity they knew they would soon be forced to sell.

3—

The Coming of the City

The attempted taking of said waters by the said plaintiffs means the destruction of a part of the body politic of the State of California, to wit: the County of Mono.

From the pleadings, Los Angeles v. Aitken, 1930

Almost from the moment california became part of the United States, the Anglo residents of the old Spanish pueblo of Los Angeles had big ideas. For no special reason other than local patriotism, they intended to make theirs the premier city of the West Coast. What we forget, in reading the story of Los Angeles, is that numerous small frontier communities had like ambitions. What set Los Angeles apart was not its bumptiousness but its astonishing success.

Outsiders didn't predict it. At the turn of the century, William E. Smythe, first executive secretary of the National Irrigation Congress, thought California growth would occur where water was naturally plentiful, especially along the Sierra and Cascade chains. Of southern California he wrote, "It is perfectly true that this charming district is not within the field of the largest future developments." Among the future growth centers, he predicted, would be the Owens Valley, that great trough behind the highest part of the Sierra, south of the Mono Basin and Long Valley.

Los Angeles wasn't listening. Its first imperial step had already been taken: to claim all the water available from the Los Angeles River, the stream on whose banks had been founded the original Spanish pueblo of Nuestra Señora la Reina de Los Ángeles de Porciùncula. In 1895 the California Supreme Court agreed with the city that it had an overriding pueblo water right, going back to Spanish rule, to the river's entire flow. Later students have concluded that this decision was in error—that the Spanish never dealt in absolute water rights but, rather, balanced competing claims. Nevertheless, the pueblo water right passed into legal doctrine.

By 1900 it was clear that even the entire flow of the Los Angeles River would not support the growth that civic leaders had in mind. Where next?

An engineer named Fred Eaton saw the answer, but he stood alone for a dozen years. As head of the privately owned Los Angeles City Water Company, he had encountered a radical notion. Just maybe, some unidentified genius suggested, an aqueduct could be built to the Owens River, 235 miles away and 4,000 feet uphill, through which Sierra Nevada water would run to the city by gravity alone. The very region Smythe had seen as a growth center would instead support the growth of Los Angeles.

Eaton saw an opportunity for public service—and great personal profit, for he had hopes of becoming the proprietor of the Owens River source. He made the wild idea his own. During ensuing years, in various leadership roles in and out of government, he pushed the plan. But not even during a term as mayor could he get many people to listen. William Mulholland, an Eaton protégé who succeeded him as chief engineer of the water company, wasn't convinced. Neither were the federal water bureaucrats. "On the face of it," one said, "such a project is as likely as the City of Washington tapping the Ohio River."

That assessment, however, overlooked the difference between the water-rich East and the generally arid West. And it made no allowance for the zest of engineers.

By 1904 the landscape of opinion in Los Angeles had changed. The city had bought out the old private water company, retaining the indispensable William Mulholland as chief engineer. Mulholland had already spent several fruitless years looking into water sources closer to home. Meanwhile, the new U.S. Reclamation Service, the dam-building and irrigation agency established in 1902, had begun planning an Owens River project of its own, strictly to benefit Owens Valley agriculture. Eaton's madcap dream looked plausible now; it was also about to be foreclosed.

The Reach

In the fall of 1904, Eaton and Mulholland made a secret trip to the Owens Valley of Inyo County.

It seems a long way now; it seemed much longer then. Traveling north and east from Los Angeles by buckboard, they first had to cross the mountains that ring the Los Angeles Basin. Next came the Mojave Desert, fiat, heat-blistered. Presently a shadow began growing on the left, the southern reach of the Sierra Nevada. Converging on the escarpment, the road crossed the line into Inyo County. To the right appeared a vast saline sea, larger though far shallower than Mono: Owens Lake, the terminus of the Owens River. North from it stretched a grand valley, about 100 miles long, 4,000 feet above sea level, between the highest Sierra peaks on the west and the somber masses of the Inyo and White mountains on the east. Mountain creeks came down from the Sierra, one after another, to join and swell the river.

North of the town of Bishop, the fertile valley ended and the land tilted upward into Mono County. The road's course grew rough but the river's was rougher: it vanished from view in a narrow slot, the Owens Gorge, eroded into the volcanic Bishop Tuff. At the top of the 2,500-foot ascent perched Long Valley, the misnamed basin, more round than long, from which the tuff was long ago ejected. A few miles further upstream, at the northern edge of Long Valley, the Owens had its beginning in a group of gushing springs.