Preferred Citation: Larkin, John A. Sugar and the Origins of Modern Philippine Society. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft4580066d/

| Sugar and the Origins of Modern Philippine SocietyJohn A. LarkinUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1993 The Regents of the University of California |

To my many Filipino hosts

and to the late Donn V. Hart,

without whom . . .

Preferred Citation: Larkin, John A. Sugar and the Origins of Modern Philippine Society. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft4580066d/

To my many Filipino hosts

and to the late Donn V. Hart,

without whom . . .

Preface

Recently, the Philippine people have endured a series of harsh blows—from nature in the form of earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, killer typhoons, and floods and from the government through its mismanagement, abuse, neglect, and corruption. Such events have saddened me considerably, for during my many years of study in and about this country I have developed a great affection and admiration for its citizens. They have been open and hospitable to me, and I can only offer this book as a token of my appreciation. Here I try to explain in what I think is a sympathetic fashion how colonialism and the international export economy shaped their lives. Hopefully, with the ebbing of neocolonialism, Filipinos can put the larger control of their own destiny more to the service of the many. They deserve a better fate.

A book of this dimension could not exist but for the assistance of many friends and organizations. As always, the late Adelina Ventura and her children, now scattered to the winds, supplied a roof, encouragement, or a quick translation whenever I appealed to them. Norman Owen, Ben Kerkvliet, Yoshiko Nagano, and Ronald R. Edgerton read portions of the manuscript and gave me the benefit of their valuable comments. Sheila Levine eased the process of moving the manuscript along to publication, and Doug Perrelli patiently created meaningful maps from my imperfect directions. Dore Brown and Joanne Sandstrom did an excellent job preparing the manuscript for publication. Serafin Quiason, my kabalen , offered me special access to Pampanga and loaned me the services of the able Roland Bayhon to lighten the burden of archival work. Lina Concepcion not only opened the Philippine National Archives to me, she also listened sympathetically to the problems of a struggling researcher. And Janet

Baglier, my wife, did the major hand holding that saw this book to completion. It is customary to absolve the above for any errors in the text, and I do so; as well, there are certainly fewer mistakes because of them.

Others who supplied either materials, expertise, or moral support include the late Domingo Abella, John and Myrna Adkins, Marysol Aizpuro, Dorothy Baglier, Charles Bryant, Nita and Jim Burris, Linda Casper, Amado Castro, Rosendo Coruña (of SPCMA), Nicholas Cushner, Marina Dayrit, Noel de Paula, Eden Divinagracia, Evelyn Dizon, the late Fred Eggan, Oscar and Susan Evangelista, Doreen Fernandez, the late Frank Golay, Mitchell Harwitz, Namnama Hidalgo, Karl Hutterer, Natividad Jardiel, the residents of Jesuit House in Chicago, Carl Landé, Emma Larkin, Judith Larkin, Sarah Larkin, Sean Larkin, La Salle Brothers of Bacolod, Violeta Lopez Gonzaga, Stephen Moscov, Barbara Nowak, Mario Nuñez, Akil Pawaki, Kathleen Revelle, the J. B. L. Reyes family, Norman Schul, the Smith, Bell & Co. staff, Wilhelm Solheim, the late Tony Tan, and Pedro Tison.

Grants for time away from teaching came from the American Council of Learned Societies, the Center for Asian and Pacific Studies at the University of Hawaii, the U.S. Department of Education (Fulbright Office), and the State University of New York at Buffalo. The School of Economics at the University of the Philippines, Diliman, loaned me an office for a year and facilitated my interaction with its knowledgeable staff.

Unfailingly the staffs at the following repositories assisted me in my search for obscure materials: Newberry Library, Lilly Library, Lockwood Library (SUNY/Buffalo), Colgate-Rochester Divinity School Library, Harvard Library, Yale Library, Library of Congress, New York Public Library, University of Michigan Library, University of Hawaii Library, Cornell Library, Hawaiian Sugar Planters Association Library, University of the Philippines Library, Ateneo de Manila University Library, Philippine National Library, U.S. National Archives, and Philippine National Archives.

Finally, at a time when my spirits were especially low, Donn V. Hart gave me a much needed boost in morale that put me back on the track to finish. In his own ebullient manner he kept me on that track until the time of his death. For his caring ways and his contributions to keeping Philippine studies alive, I include him in my dedication.

One note on names and sources: with Spanish proper names and references I have used Spanish accents, but with Philippine names I have adopted the local practice that drops those accents.

QUEZON CITY, JANUARY 1992

One

Introduction

Fortunes have been made in this Colony in cane-sugar.

John Foreman, The Philippine Islands (1906)

Sugar is chronically in oversupply, because it is one of the few products that can be produced in almost any country in the world.

Philippine Sugar Handbook (1972)

This book examines the influence of an export sugar economy upon the people4 of the Philippines through a study of its two most important sugar-producing areas. Although natives of the archipelago cultivated and chewed sugar cane before the coming of the Spaniards, the milling, consumption, and shipping abroad of brown sugar followed in the wake of the sixteenth-century Iberian conquest, when Catholic friars and Chinese entrepreneurs introduced the technology and created the first middlemen networks. Commercial sugar thus became intricately associated with the colonial experience. Eventually, the exporting of sugar brought the Philippines into direct contact with the outside world and provided a chief means for the introduction of new and foreign ideas into native society and culture. To a great degree, then, "sugarmen" shaped Philippine social and economic life. The main contention here is that the sugar industry had adverse effects on economic development, that it led to wide, harsh social and economic cleavages among the Filipino people, and that it skewed political power in the archipelago, in colonial times and later.

Social historians have commonly accepted the tenet that modern Philippine society and culture derived from the interaction between native traditions and Western ideas introduced through colonialism. They have acknowledged as chief vehicles of occidental penetration the Catholic religion and the American educational system, as well as the forms of government introduced by the two powers. Less well recognized, however, is the role of economic enterprise in the molding process, even though commerce has long been a staple of archipelago activity.[1]

Scholars, for example, have taken it for granted that commerce had minimal influence upon social life during the first two and a half centuries of Spanish occupation, when the tripartite galleon trade operated between China, Manila, and Acapulco.[2] This notion, however, is only partially correct, for, even in this early era, a pattern of foreign domination of export enterprise was already emerging. At this time, too, began the collaboration between members of the native elite and foreign merchants that has remained a characteristic of Philippine business ever since. This pattern of cooperation strongly informed the native socioeconomic structure and, subsequently, nationalist attitudes toward international and domestic affairs. The early choice, too, of sugar as a primary cash crop has played an important part in Philippine social development, for sugar production carries with it certain social ramifications that derive from its particular technology and from the nature of world market conditions.

Recent studies of the sugar cane industry in diverse regional and national settings have affirmed its role as a social determinant.[3] The methods of crystallizing sugar from cane syrup originated in India during the first millennium B.C.E. , and Arabs subsequently introduced this technology to the Mediterranean world in the seventh and eighth centuries. The beginnings of the modern mass production-mass consumption market, however, date back to the seventeenth century, to the time of the formation of estates in the French and English colonies of the Caribbean. Here European planters used African slaves to grow cane and operate mills.

Slavery proved an expeditious system because of the peculiar labor needs of planting and harvesting cane. The two activities follow closely upon one another: the growing period for cane is about one year, and the new crop must go into the ground as soon as the old one leaves. Moreover, because cane begins to deteriorate immediately upon being cut, it must be delivered rapidly and in proper amounts to keep mills operating efficiently. The harvest season, therefore, is very busy, and only a large, well-disciplined labor force capable of toiling in the tropical heat can meet its demands. During nonpeak periods, just a fraction of those workers are required to weed and maintain the fields. Thus, unpaid chattels best fulfilled the requisites of this sector of the industry.[4]

Milling—a capital-intensive activity that utilizes machinery to grind the cane, boil the extracted syrup, and crystallize it into brown sugar—is the other component of sugar production. In various eras owners have employed animal power, windmills, waterwheels, and steam and electricity to run their factories. Mechanical advances have gradually reduced labor costs, enlarged grinding capacity, speeded up manufacturing, and improved the purity of the end product, thus yielding ever greater profits to mill

owners. At the same time, because of the general availability of an abundant, cheap work force in tropical and semitropical climes, the invention of laborsaving field machinery has not kept pace with the technological improvements in milling. Only recently in places like Australia and Hawaii has sophisticated mechanical harvesting equipment come into use.[5]

During the eighteenth century, slave-produced sugar became a staple in the diet of Europe's expanding industrial labor pool. In the Caribbean world, sugar created a society of rich landowners and millers living with poor field hands in closed agricultural communities known as plantations. Over time the West Indian living pattern changed somewhat as more planters became absentee, but the socioeconomic dichotomy persisted in the manufacture of sugar. When the sugar industry spread to Africa, Asia, and Oceania, the legacy of slavery lingered on in the bifurcated income distribution of sugar societies. Sugar farming tended to find a niche in regions where the labor force could be turned to or coerced into doing field work for low wages. Henceforth, production became associated with extremes in social structure: the very poor who cultivated and cut the cane, and estate owners and millers who controlled the conversion of cane to

sugar.

Sugar's status in the modern world economy helped perpetuate this social division. The sugar market faces two givens: first, sugar, which can be produced in numerous settings, is a taste additive rather than an essential food, and second, world sugar supplies have usually exceeded demand. Sugar is a sweetener and preservative, the carbohydrate sucrose extracted chiefly from sugar cane in the tropics and from sugar beets in more temperate climates. It enhances flavor in food but has little nutritional value. Sugar contributes much less to human food requirements than, say, cereal staples, so it can be sacrificed from the diet more readily than the latter in times of privation and high prices.[6]

Because so many countries historically have fulfilled their own need for sweeteners, only a few areas, chiefly North America, northern Asia, and Western Europe, have had to import large quantities of sugar during the past two centuries. From the early nineteenth century on, the expansion of European and American beet sugar cultivation has somewhat reduced the dependence of even those markets on cane sugar. As a result, world sugar supply, except during wartime, has matched or surpassed demand, and sugar has usually remained a buyers' market; moreover, attempts to form international sugar cartels have consistently failed. To stay competitive under such conditions, sugar exporters have faced two options: to seek privileged access to specific markets, the quantity of export sometimes adjusted downward by some kind of quota limitation, and/or to reduce

production costs through investments in milling technology and minimal wages and thus eke out higher profits. Whether in capitalist areas like Hawaii and Louisiana, in colonies such as the Philippines and Java, or in the socialist milieu of Cuba, market forces have reinforced the old pattern of powerful mill owners and grossly underpaid field hands.[7]

Those who adhere to Immanuel Wallerstein's theoretical division of the "capitalist world-economy" into core industrial, semiperipheral, and raw material producing peripheral areas will identify the Philippines as a typical peripheral region given over to sugar production. Certainly that characterization aptly applies; however, visualizing insular society as structured like other peripheral areas offers only a partial view of its nature. Wallerstein's analysis refers mainly to political-economic formations and leaves out the social and cultural dimensions that specifically identify a human community; hence, such an approach will scarcely satisfy the concerns of social historians.[8]

The very diversity of the Filipino population makes it difficult to portray clearly the impact of the sugar industry. The early Philippines where sugar manufacture first took hold was not a unified society, but rather, several communities separated along ethnolinguistic lines. The great cultural traditions of India and China that had provided central organization and a common identity to other parts of Southeast Asia had not reached the sparsely settled archipelago, save for the southernmost islands, where Islam held sway. Spain managed to establish a uniform colonial government and to convert most denizens to Catholicism, but, because of the island nature of the country, regional variation—linguistic, ethnic and economic—has persisted ever since. How sugar affected such a heterogeneous population poses a problem for investigators.

A useful means of assessing the influence of the sugar industry upon Philippine society and culture resides in cultural ecology, a branch of anthropology that seeks to comprehend the creative way humans interact with their environment and the culture that results from those interactions.[9] Julian Steward points out that, as a means of understanding, cultural ecology rejects the contentions of human ecologists that the environment determines human adaptation, as well as those of anthropologists who regard the physical environment as far less important than cultural diffusion in shaping human adaptation. He maintains, rather, that "cultural ecology pays primary attention to those features which empirical analysis shows to be most closely involved in the utilization of environment in culturally prescribed ways."[10]

According to Steward, to understand the interplay between environmental exploitation and society, it is necessary to consider its "culture

core," which he defines as "the constellation of features which are .most closely related to subsistence activities and economic arrangements. The core includes such social, political, and religious patterns as are empirically determined to be closely connected with these arrangements."[11] He then describes the method to uncover the interaction between culture core and society:

First, the interrelationship of exploitative or productive technology and environment must be analyzed. . . .

Second, the behavior patterns involved in the exploitation of a particular area by means of a particular technology must be analyzed. . . .

The third procedure is to ascertain the extent to which the behavior patterns entailed in exploiting the environment affect other aspects of culture.[12]

In the Philippine case cultural ecologists would conclude that the methods by which Filipinos produced sugar shaped to a large degree their cultural and social behavior, especially those aspects closely associated with the industry. In regard to millers and landowners, their capitalist outlook and extravagant behavior sprang from their control over and ownership of land and energy-efficient equipment. As for field hands, the way they cultivated cane as tenant farmers or plantation workers molded their social behavior and attitudes. Where tenancy and barrio communal living prevailed, a cooperative outlook developed that expressed itself not only in mutual assistance, but also in joint resistance to oppression. On isolated haciendas where wage labor dominated, social anomie and a sense of helplessness became the behavioral norm. Moreover, because the industry grew to such importance, in terms of political power, economic prestige, and the great number of people who participated in it, the attitudes of both rich and poor sugarmen spread throughout the archipelago. Hence, to understand the values and attitudes of Philippine society, one needs to understand something about the manner in which the sugar industry functioned.

Large-scale sugar production eventually spread to regions possessing diverse social and labor systems; therefore, the resultant sugar society exhibited considerable variation in structure, norms, and behavior. To describe change in all these places in any meaningful fashion would require a work of massive proportions; instead, I have opted to focus upon just two areas, northern Pampanga and western Negros. Besides encompassing the two largest sugar-growing regions in the country, they also had very different histories and social circumstances. Long-settled Pampanga ben-

efited from its proximity to the colonial capital of Manila and began making sugar in the seventeenth century; Negros, more isolated, remained a wilderness until the opportunity to grow sugar led to its nineteenth-century transformation into a plantation economy. Landholders in the former area built their sugar agriculture upon a traditional patron-client relationship with their tenants; in contrast, newly arrived Negrense entrepreneurs exuding a frontier spirit established and operated haciendas through the more efficient, economical, and flexible use of paid labor. The determinants of the sugar market were common to both.

The sugar industry and Philippine society interacted in complex ways, and concentrating on two disparate local regions as well as upon the insularwide and international levels enhances comprehension of three dimensions of that interaction. First, examining what happened to Pampanga and Negros reveals the regularities in sugar's impact upon local farming areas. The development in both places of the classic pattern of very rich and very poor, millers and field hands, argues persuasively for the universal determinism of sugar in societal development.

Second, observing the contrasts between the two regions, even under the impact of sugar, indicates just how the original culture of each endured and continued to shape local society. Farmers could and did grow cane under differing systems of labor organization, and the degree of sugar's sway varied from place to place. Especially in Pampanga old traditions proved persistent. Moreover, ideas about society and social organization formed in the provinces sometimes affected the way people thought and acted at the insular level. In brief, the influence of the sugar industry did not move just one way.[13]

Finally, portraying broad changes in the industry focuses attention upon the emerging supraregional sugar elite, a small number of powerful and influential individuals and families, many of them from Negros and Pampanga. Because of their political clout and extravagance, derived from their ownership of vast lands and mills, they heavily influenced Philippine society, government, and economic life. On one hand, elite leadership at the local level encouraged the kind of regional identity and loyalty that has operated to the detriment of national political unity; on the other hand, their business and lobbying activities at home and abroad led to the acceptance of a national economic purpose on behalf of their industry. They forged social links in every sugar-growing area, and, through their interactions and business contacts with Europeans and Americans, they became internationalists. At the same time, their need to secure overseas markets strengthened the ties of dependency and neocolonialism that have characterized modern Philippine-American relations.

This book is not exclusively about millers and planters, however, but also about those who toiled physically in sugar factories and fields. They too contributed to the development of both regional and insular culture, for, although their individual voices were seldom heard, they expressed themselves collectively through their work and through figures who represented them in various ways. Sugar hands contributed ideas about social and labor organization, about cooperation in the accomplishment of tasks, and about resistance to oppression and exploitation. Those who articulated their laments and aspirations ranged from rural rebels and messiahs to labor bosses, intellectuals, and politicians. Sugar's contribution to Philippine society and culture, then, includes the thinking and acts of its poor.

I use the term "sugarmen" throughout the book because others in the Philippines have and do employ it to refer to those who participate in the industry. I do not mean to imply that sugar was exclusively a male preserve, however, for it was decidedly not so. Women, young and old, labored in the fields, especially during planting and weeding season, and they participated in family derision making on economic matters. Some women owned sugar lands in their own right, supervised work on their holdings, and made all kinds of investments from sugar profits. The sources, however, proved somewhat stingy in yielding specific information on the activities of women and children, for in the Philippines the tendency is for men to receive much of the public attention in all economic and political endeavors, even when others deserve a goodly share of the credit. So, while I have not been able to describe the particular impact women may have had upon the industry, let it be recognized that they played a substantial role.

Broadly speaking, modern historians of the Philippines have pursued their subject by adopting either a general or a local approach. With the first they have sought to form an overview of the progress of the Philippine state from its origins in the prehispanic, protohistorical past to its more integrated national present. This approach has chiefly emphasized political evolution, especially in the Manila capital complex and the surrounding Tagalog-speaking region. The other avenue has focused upon change in circumscribed, variously defined subregions within the archipelago. Theory has it that such studies, when available in sufficient number and then integrated, will provide a more comprehensive vision of the Philippine experience. So far, local historians have adopted mainly a socioeconomic perspective, paying some attention to geographic, demographic, and political detail.[14]

Each approach has served an important role in illuminating Philippine history, but both have their shortcomings. The first concentrates too

narrowly on Manila-based happenings and assumes, as those who study national centers usually—and sometimes incorrectly—do, that capital events and politics serve as an accurate measure of the country's general development, mood, and sense of unity. The local studies, while concerned with occurrences in rural areas of a vastly agricultural country, have tended to be too region-specific and have merely provided samples of one. Furthermore, because each local history has stressed the unique aspects of its particular region, broad comparisons with other areas have proved awkward. The Philippines, in other words, is more than a nation in the making or the sum of its diverse regional experiences. A need exists for consideration of the ways the insular center and outlying regions have interacted and how and what influences have passed between them. A history of the sugar industry can offer a view of the linkages between the two spheres.

This book, then, is neither regional nor national history as heretofore done, but, rather, comparative and integrative history. Comparative history works best when the areas contrasted share common experiences. During the early centuries of Spanish occupation, Pampanga and western Negros bore little resemblance to one another; thus, I have treated the two regions during this time as distinct. However, in modern times, as their histories converged under the impact of sugar, I have intermingled the two accounts more. By looking at ways each area responded to insularwide forces, I have tried to add new insight into colonialism, the frontier, the Philippine Revolution, the independence struggles, and rural unrest, to understand better the diverse response of Filipinos to economic crises, political events, and social differentiation.

In the end, sugar created a native elite, prestigious and powerful who, despite their disparate provincial origins, acted together with the collusion of foreigners to shape the course of Philippine modernization. For more than a century and a half, sugar represented the most important and influential sector of an insular commercial life that this elite, with rare exception, exploited almost exclusively for their personal advancement. Their conspicuous consumption contributed not so much to the progress of the islands as to the outflow of cash and to the inequitable colonial economy. Among sugar workers the maldistribution of profits created not a consuming public but permanent pockets of poverty, and attempts to ameliorate their circumstances came mostly to naught.

In 1982, Philippine newspaper columnist Arlene Babst wrote the following about the contemporary elite, whom she called "eternal":

I have been charged with belonging to this elite group myself. . . . The charge, to be fair, should be modified to the peripheries of such an elite group. At the risk of "treason" to this group, I must say that even one who has ties to it recognizes it

as an enormous obstacle in the process of building a kinder society.

This elite group has had more power than it should; more wealth than it has fairly worked for; more privileges than it deserves.

It has failed as a social institution because it has not used its leadership to better the lot of the majority; sadly, it has consistently bettered mainly its own lot, not caring enough about that majority which sustains the elite.[15]

Sugar no longer steers the Philippine economy, but its legacy endures in a native elite largely insensitive to the needs of the underprivileged.

Pampanga and Western Negros

Since the mid-nineteenth century numerous regions of the Philippines have yielded export sugar, among them Batangas and Laguna provinces on Luzon, southern Negros Oriental, and the islands of Panay and Cebu. More recently, the Cagayan Valley of far northern Luzon, and Davao Province on Mindanao have become significant sources. The fields of Pampanga and Negros Occidental, however, have remained the two most consistently productive areas in the archipelago (see map 1).

The sugar lands of Pampanga and western Negros do not conform to any provincial boundaries; rather, they follow certain edaphic and terrain features of the Central Luzon Plain and Negros Island, respectively. In both places, where the soil is a sandy, friable loam and the grade not too steep, farmers have regularly planted cane for a century or longer. The Negros lowlands and Pampanga plain where sugar predominates comprise some of the finest and most extensive stretches of flat alluvial farmland in the archipelago.[16]

Pampanga's sugar area forms a rough triangle with its southern apex at a point where Lubao and Floridabianca, Pampanga, meet Dinalupihan, Bataan (see map 2). The western leg of the triangle follows the slope of the Zambales foothills as far as Barrio San Miguel in the capital of the province of Tarlac. The eastern line skirts the edge of the delta of the Pampanga River, follows the San Fernando River, bends toward the slopes of Mount Arayat (1,026 meters), then slants toward Tarlac. The northern cap en-compasses the lands of Hacienda Luisita in Barrio San Miguel. Southern Tarlac was one of the last parcels of the Central Plain settled, and it still has the lowest population density in the area. Alongside the southeastern flank of sugar lands rise the Pampangan towns of the Pampanga River and the Candaba Swamp, very old communities where rice cultivation and fishing have long flourished. Even within the sugar area, because the lowest land has a hardpan suitable for growing rice, farmers possess a degree of

Map 1.

Philippines, Major Sugar-Producing Areas, 1939

flexibility in what they plant and on occasion convert to cereal production when sugar prices fall too low. Hence, the expanse of sugar varies somewhat from season to season. In a good year such as 1970, planters devoted 53,291 hectares to the growing of cane to feed the three modern mills, or centrals, that service the region.[17]

The enormous debris from the 1991 explosion of Mount Pinatubo (1,610 meters) has altered somewhat the physical shape of the Pampanga region, but the effects have mainly been felt in the lowland rice-growing areas. Some sugar farmers have even reported better yields as a result of the fallout of pyroclastic materials.

Pampanga has long benefited commercially from its proximity to Manila. Early on planters and middlemen shipped their product in light sailing vessels called cascos down the shallow streams entering Manila Bay. In the late nineteenth century the main trunk of the railroad that runs north from the capital reached Pampanga. Subsequently, feeder lines branched out to meet the industry's needs, and since then the raw sugar has gone mainly by rail, either to the port, from where it is shipped overseas, or to refineries that supply the insular market.

The sugar region encompasses eighteen towns of Pampanga, four of Tarlac, and one of Bataan, where cane has been grown on a significant scale. Provinces in the Philippines break down into town-sized municipalities subdivided into smaller communities known until recent times as barrios (currently barangays ). In central Luzon, as elsewhere, each town has its commercial, social, and administrative core, usually called the poblacion , where stand the Catholic church, the municipal hall, the more substantial residences of the rich, a covered or open air market, and bigger shops, arranged around or near a central green plaza.

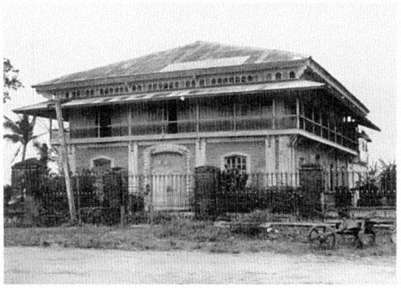

Change, however, is coming rapidly to the Pampanga region. The traditional homes of the wealthy with their wood and stone construction and sliding capiz-shell windows have given way to modern houses of cement and stucco with glass jalousies. The growing trend in the area is toward residential subdivisions separated from the commercial districts. The three biggest communities—provincial capitals San Fernando and Tarlac, as well as Angeles, now an incorporated city—have a somewhat different layout with their chief activities spread along main streets, and they have lost the old-fashioned hispanic character of the smaller towns with their plaza complexes. The former U.S. installation of Clark Air Force Base contributed to the distinctive character of Angeles.

In the barrios, usually comprising from one hundred to three hundred families, reside most of the workers in the area, including the tenants who actually grow the cane. They live chiefly in airy nipa palm and bamboo

Map 2.

Pampanga, Major Physical Features

houses and obtain their everyday necessities at small stores called sarisaris . Better-off farmers might have electricity, and a new feature of the countryside is the more permanent cinderblock house with metal sheet roof purchased with "Saudi money" earned abroad by the adventurous Capampangan. Within the past two or three decades barrios have become much more crowded, for Pampanga has the second highest density among all the provinces in a populous country. The 1980 census revealed that for the first time urban residents in Pampanga outnumber rural ones.

All the towns have in common a central place where barrio folk visit to transact business, to socialize, and to find entertainment. Communities in Pampanga are accessible by a strong network of local, provincial, and

Map 3.

Pampanga, Main Roads

national roads over which stream jeeps, buses, tricycles, and horse-drawn calesas that make travel easy and fairly inexpensive. The many roads and short distances between settlements have facilitated strong social interaction among the local denizens. The predominant language here is Capampangan, one of several important regional dialects in the country; however, one also hears the national language, Pilipino (Tagalog), spoken, especially in town centers. In Tarlac, Capampangan is interspersed with the Ilocano spoken by descendants of settlers from the northern Ilocos area who joined migrants from Pampanga on this nineteenth-century frontier.

The northbound expressway out of Manila passes by San Fernando and Angeles, bisecting the heart of sugar country; near Barrio Dau the highway

becomes a typical provincial road as it proceeds toward more rural Tarlac. Arteries off this central highway offer entree to old towns with many fine examples of colonial architecture, as well as to barrios large and small (see map 3). In such communities people tend to be outgoing and curious toward strangers. Two things are likely to strike the contemporary observer: the myriad children one sees everywhere and the variety of economic activity. The province possesses not only a dense population, but a young one as well. The imperative of maintaining an economy for the many seems dear, and to meet that need enterprising Capampangan have sought numerous solutions in the face of a currently depressed sugar industry. Interspersed among the still extensive sugar fields are paddies, now double cropped and planted with strains of the "miracle rice." Padi dries everywhere, on cement roads, in house yards, and on basketball courts, and seed beds turn deep green with new seedlings. Piggeries appear frequently on roadsides, as do retail and repair shops and fruit and fresh coconut (buko ) stands. Perhaps sugar will revive one day; in the meantime, the rice, pigs, housing subdivisions, and stores suggest that the Capampangan avidly seek to diversify their agricultural economy.

On Negros Island a forest-covered central mountain spine dominated by the dormant volcano Mount Canlaon (2,465 meters) separates the western from the eastern coasts (see map 4). Numerous rivers flow down the sides of this chain of peaks, carving deep cuts and providing irrigation and alluvium to the crop lands below. Gradually rising plains surround this cordillera from the northeast to the southwest, and where the slope is not too steep farmers plant their cane. The flatest sections of the coastal littoral drain too poorly for sugar, and there farmers grow rice or other crops; but not far inland, from Kabankalan to San Carlos, stands an almost continuous band of fields that identifies Negros as the premier sugar region.

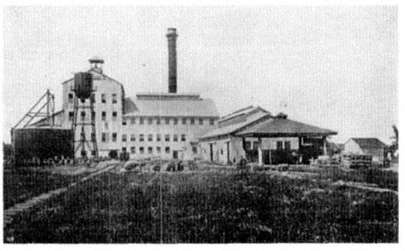

Almost all the sugar lands lie within twenty-two municipalities of Negros Occidental[18] and the portion of Vallehermoso, Negros Oriental, that belongs to the San Carlos mill district. In 1970 Negrense hacenderos devoted 190,592 hectares to sugar cane more than three times as much as did the Capampangan—which they shipped by truck or narrow-gauge railway to the region's thirteen centrals. Western Negros lacks good harbors, and before World War II exporters shipped mainly from Iloilo across the Guimaras Strait on neighboring Panay; however, raw sugar now reaches its overseas destinations via lighters that transport it from the long pier at Pulupandan or from the wharves along the shallow coastline near several centrals to oceangoing vessels off shore.

Bacolod serves not only as the capital of Negros Occidental, but also as its hub of commerce, entertainment, and transportation. While five other municipalities—Silay, Cadiz, Bago, San Carlos, and La Carlota—boast the

status of incorporated cities, only Bacolod truly seems like an urban center. A sprawling market area with a variety of shops and restaurants abuts the large central plaza with its big church and other religious buildings. The city contains colleges, one of the most impressive provincial capitols in the archipelago, and the local offices of the major planter organizations; furthermore, its hotels, movie houses, and other amenities attract visitors from all over the region. From one of its several terminals commence all journeys through sugarlandia (see map 5).

Travel through Negros proves more difficult than through Pampanga because of the greater distances between communities, the poorer road system, and the less frequent, more expensive public transportation. A two-lane highway parallels the shore slightly inland all the way around the island, and through sugar country is mostly macadamized. Off that trunk, feeder roads and paths, frequently gravel and dirt, head inland. Since their main traffic is cane trucks, they become rutted, and access to and from most haciendas is best accomplished by private vehicle.

A highway running northeast from Binalbagan makes it possible to drive through the middle of sugar country. Part hard surface, part gravel, the highway passes through fields of tall cane that block the view on both sides. In the midst of this overwhelming expanse rest the quiet, spare towns of Isabela and La Castellana, for most of those who own land in the vicinity either reside on their haciendas or elsewhere. Not far beyond La Castellana the hills start to rise, and the road crosses the central chain near Mount Canlaon and connects with the main highway along the east coast just above Vallehermoso. From there it is only a short distance to the busy mill town and port of San Carlos.

Along this portion of the coast live speakers of Cebuano, revealing their origin on the neighboring island of Cebu. Only as one proceeds toward the great northern shelflands does the language gradually shift back to the Ilongo of the western Visayas, the dominant tongue in Negros sugarlandia. The northern cap contains large fertile tracts with the highest cane yields in the whole region. This section from San Carlos to Victorias, with its mixture of languages, its rich soils, its timber stands and newer towns, reflects its frontier status as recently as seventy years ago. The cathedral at Silay and the quiet Spanish plaza of Talisay with its stately homes and church offer a contrast to the structures in later-settled northern Negros. The closed sugar mill on the outskirts of Talisay not far from Bacolod serves as a reminder that the sugar industry currently faces a serious economic crisis.

While Negros Occidental has traditionally broken down into the same municipalities and barrios as Pampanga, sugar workers (duma'an ) in the former area do not usually live in barrio communities but on haciendas in

Map 4.

Negros Occidental, Major Physical Features

the immediate vicinity of their employment. Such plantations vary in size from as small as five hectares to as large as many hundreds, and their borders do not necessarily coincide with any political boundaries.

Ruttan described the hacienda, a typical one, on which she undertook research in 1978, in the following manner:

From the town plaza of Murcia, a sand and gravel road passes through several haciendas and leads after three kilometers to

Map 5.

Negros Occidental Main Roads

Hacienda Milagros. A large acacia tree marks the place where the road splits in two, continuing to the left through other haciendas and entering Hacienda Milagros to the right. There is no gate or fence, but the boundaries of the property are known to all who live on its grounds. Two concrete buildings are situated close to the entrance. One is the warehouse (bodega ) where the tractor and cane trucks are parked, the implements and sacks of fertilizer are stored, and where the small office is

housed. It is the central place of the hacienda: here each morning the laborers assemble for the assignment of daily work, and here the weekly payment of wages takes place. The other building is the sacada house . . ., the living quarters of the migrant laborers during milling season, and partly occupied by the security guard and his family. Behind these buildings some twenty-two bamboo and nipa houses line a narrow, winding path. There are the houses of workers and salaried employees—the overseer and timekeeper, foremen and drivers. Across the fields on the northern side of the hacienda is a second group of ten houses built along a river, while a third cluster of six houses lies further downstream. Eight more houses lie scattered in the hacienda. Vegetables and fruit trees are grown in the small, well-kept yards. The house lots border on the sugarcane fields, and when the cane stands tall it hides the houses from view.[19]

Sugar laborers rarely leave the haciendas, for their workdays are long, and they can buy most necessities in shops on the premises. Their isolation, their strong dependence on their jobs, and their constant supervision by management personnel have made the duma'an shy—more so than the sugar tenants or casamac of Pampanga. Only recently have conditions in Negros become so harsh that on a number of estates some duma'an have resorted to protest and to union organizing. Nevertheless, the strongest opposition to landlord control remains among those who have joined the New People's Army (NPA) on the fringes of sugarlandia or among the political demonstrators in. the streets of Bacolod.[20]

Hacenderos, at the same time, seem more outgoing and gregarious, usually eager to defend the vaunted Negrense way of life, by which they mean the planter style of doing things. Planting consists of borrowing from the bank enough money to have others place a crop in the ground in hopes of gaining great profits. If the balance sheets look good, spend those profits lavishly; if they look bad, borrow more and replant. These hacenderos perceive themselves as gamblers, forever ready to raise cane if credit is available; however, they do not appear as willing as the Capampangan to gamble on alternate investments to sugar. Despite a recent tightening of bank funds in the face of poor overseas market prospects, despite a deterioration in the quality of the soil, and despite the mounting threat of the NPA, the majority of Negrenses remain committed, more so than the Capampangan, to the monoculture that has sustained them, identified them, and shaped their way of life since the nineteenth century.

No matter how else the hacenderos from Negros and Pampanga differ, they respond alike to the physical elements that have long determined their

agricultural calendar. Pampanga and western Negros have similar growing seasons susceptive to an annual weather cycle prevailing throughout tropical Asia. Usually the southwest monsoon begins to blow in May and brings an increased amount of moisture, frequently in the form of torrential rains, to fields left dry by the prevailing northeasterlies. The rains abate in November, and farmers commence the harvest of cane planted the preceding year.[21]

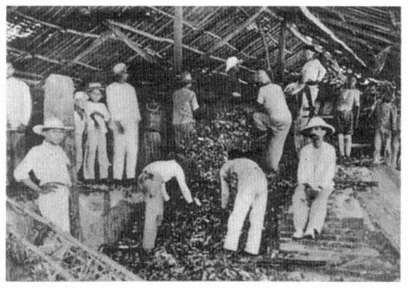

From the dissipation of the southwest monsoon until mid-May, gangs of workers take to the fields where they laboriously cut, trim, and load the cane onto assorted vehicles—carts, trucks or tram cars, depending on the location of the hacienda and on the milling district—for transfer to centrals. The cane reaches the central according to an intricate schedule designed to avoid backlogs that would allow the sucrose-laden stems to deteriorate. What complicates this process is that the Philippine sugar industry is structured differently from that in other countries, for the central operators do not, for the most part, own or manage the majority of farm property in their districts. Rather, these lands belong to numerous private planters who contract with the mills to process their cane for a share of the finished raw sugar. Thus, each central must arrange its grinding to accommodate the harvesting timetables of its numerous clientele.

Meanwhile, the emptied fields must be replowed, harrowed, fertilized, and planted once more with foot-long cuttings from the tops of the cane. In some select fields the stubble is cultivated, and another crop grows from the stools, a process known as ratooning. Later on, the young cane crop requires weeding and cultivating to assure good growth, and farmhands pass along the rows several times with plows and hoes accomplishing those chores. With the overlap of planting and harvesting that necessitates a large manual labor force, even women and children find employment in the fields. Planters also normally hire temporary workers from neighboring regions to cut and load cane.

During six or seven months each year, life in sugarlandia revolves around the frenzy of making raw sugar, but in May the pace slackens. As the southwest monsoon reasserts its domination, field work comes to a close, most mills shut down, and migrant laborers return home. All that remains of activity are the repairs around the haciendas. While the next crop matures, even the business of marketing sugar lags.

For those who still plant and mill cane the seasonal rhythms are old ones.

Two

Foundations, 1565-1835

A riddle in the village goes like this: The head is downwards while the tail is upwards. The answer is sugar cane.

Historical Data Papers, Barrio San Pedro, San Simon, Pampanga(1953)

Although the sugar industry achieved a foothold in the Philippines between 1565 and 1835, it had little impact on native society and commerce. Sugar became a part of Filipino diet and a minor component of local and overseas trade; however, Spanish disinterest in cash crop farming and modest world demand hindered growth. Despite slow development, at the end of this era the industry was preparing for more rapid expansion. Knowledge of basic techniques of sugar production improved, new plantation areas began to open, and export houses appeared in Manila. By the early nineteenth century, Philippine sugarmen were poised to take advantage of improved international market conditions occasioned by the onset of the Industrial Revolution and revised colonial economic policies.

From Sugar Cane to Sugar

Prehistoric immigrants to the archipelago brought with them techniques for growing cane, but only in colonial times did sugar production and commercial uses for sugar develop under foreign tutelage. Saccharaum officinarum , true sugar cane, has many relatives of the botanical family of tall, internoded grasses called graminaceae —cogon, talahib, and tigbao, for example—that grow wild all over Southeast Asia and the Pacific islands. It appears that at some indistinguishable time in the past sugar cane was domesticated somewhere in Southeast Asia and taken by Austronesian-speaking migrants to the southern Philippine Islands. From there its cultivation and use gradually extended northward.[1] Precolonial inhabitants of the islands chewed it as a treat or as a means of assuaging hunger. Mothers employed it as a pacifier for babies, and children ate it mixed with rice. When the fourteenth-century traveler Wang Tayuan visited the archipelago, he observed that natives in different places had acquired the skill

of turning cane juice into wine. Perhaps this was the same process, described by Jesuit missionary Francisco Alzina in the seventeenth-century Visayas, of fermenting in Chinese jars cane juice mixed with a special tree bark to make an alcoholic beverage called intus . This traditional method of fermentation was preserved into the twentieth century by aboriginal Bacobos of Mindanao, who used a wooden press to express juice. Such a press, or one like it, may have originated in prehispanic times, but natives in the islands also extracted juice from some varieties of cane simply by beating two stalks together.[2]

What the early indios (native inhabitants) did not do was make sugar. When Magellan arrived in 1521, natives in the Mindanao area offered cane to his crew as a refreshment, while Spanish explorers of the Cagayan Valley in northern Luzon received similar gifts in 1591. But not sugar. Sugar was among the items of resupply requested from Mexico by members of the first permanent expedition to the archipelago in 1565. From 1571, when Manila became the established place of Spanish settlement, until the first decades of the next century, Chinese traders regularly imported sugar to the colony. The idea of manufacturing sugar and its byproducts came to the Philippines along the route of colonial conquest: across the Atlantic, via the Azores and Canaries; to the Caribbean; on to Mexico and South America; and finally, across the Pacific.[3]

Little information exists on how sugar technology initially entered the Philippines. Presumably Spaniards, who had a great taste for the sweetener, encouraged its domestic manufacture to save the considerable import cost from China. Methods of expressing juice from cane between two horizontal wooden rollers, boiling it down in earthen vessels, and crystallizing it were widely known in China and around the Mediterranean Sea, so that either Chinese or Spaniards, or possibly both, could have brought these techniques to the Philippines. Spanish friars played a considerable role in setting up sugar plantations in the first decades of the seventeenth century, and gradually, sugar making spread throughout the archipelago, first to Luzon and then to the Visayas. Local sugar slowly replaced the Chinese imported product, and as the Philippines became self-sufficient, the price dropped appreciably during the seventeenth century.[4] A kind of brown sugar, called panocha , crystallized in coconut shells with the aid of lime water, is still made today in the countryside and may date back to these early times. With increasingly widespread knowledge of how to derive sugar came a corresponding rise in its consumption by the indigenous population, especially the ruling class. Even before midcentury one Spaniard, Juan Diez de la Calle, noted that sugar abounded in the islands and served as evidence of native wealth; meanwhile, Moro (Muslim Filipino)

sultans served cakes and preserves sweetened with cane syrup as a treat to special guests. Natives learned also to concoct a kind of sugar brandy, probably basi , and by the early eighteenth century, so widespread had its use become that the Spanish government felt obliged to forbid production of this beverage.[5]

While making ordinary sugar for home use spread generally throughout the archipelago from the mid-seventeenth century on, fabrication of more highly refined grades was restricted to the religious estates near Manila and to Pampanga Province. By 1708, estates like San Pedro Tunason and Makati produced pilon sugar, that is, sugar crystallized in day molds, freer of the molasses found in more common grades of the muscovado type. Augustinians in Pasay and Jesuits in Nasugbu were making higher grade sugar by at least the 1740s, and the latter maintained warehouses on their property so that they could hold their product back until prices reached a high in Manila.[6] Processing of commercial grades of sugar may have gone back to the late seventeenth century in Pampanga, although specific references to that industry do not appear before the eighteenth. There native farmers grew cane and may even have undertaken the first stage of producing sugar, but Chinese merchants dominated the marketing end of the business, and in 1729 a Spanish governor of the province complained that the Chinese bought all the produce of the area so that they could resell it in Manila.[7]

Once sugar reached the capital city, no matter from where, the Chinese monopolized its processing and sale. They turned sugar into candy and syrup for drinks (e.g., azucar rosado , a beverage made with caramelized sugar and citrus juice) and packaged it for the slowly growing export trade in native products. A census of Manila Chinese establishments in 1745 noted that the sugar dealers' guild consisted of sixty stores, and the sweetmakers' guild contained twelve.[8] At its inception, then, the commercial end of the Philippine sugar business came under the control of foreign hands with native participation only at the level of primary production.

The Philippine sugar industry has always depended on external market conditions for its progress and profit, and during the first two centuries of colonial domination Spaniards focused their attention on the renowned trans-Pacific galleons, ignoring the development of indigenously based economic endeavors. The galleon trade, sanctioned as a compromise between mercantile interests in Spain and the Philippines, turned Manila into an entrepôt, a place to exchange highly valued Chinese textiles and wares for Mexican silver, with profits in the archipelago going chiefly to the

resident foreign community of Spaniards and Chinese. The Spanish crown remained amenable to maintaining the Philippines as a religious responsibility supported by its more profitable colonies in Latin America. Native produce had little role in this officially sanctioned commerce, although some sugar made its way onto junks returning to China.[9]

But Philippine international commerce did not consist only of what the Spanish government officially allowed; a substantial amount of semilegal and illegal trade also occurred, and Philippine goods found a minor outlet through these clandestine channels. Distance from the mother country made official supervision weak, and colonial servants learned ways to profit from overlooking the strict rules of colonial commerce. By the mid-seventeenth century, European vessels, including Dutch and British, visited Manila, and the British East India Company (BEIC) sent its first ship, Seahorse , in 1644, inaugurating trade on a more or less regular basis beginning in the 1670s. Seahorse , on its return to India, carried samples of Philippine sugar, and small quantities of it went into cargos of later BEIC voyages. By the 1750s, Nicholas Norton Nicols, a naturalized Spanish subject living in Manila, pointed out that substantial quantities of Philippine sugar reached both the Coromandel and Malabar coasts of India, Bengal, Persia, and China.[10] The early pilon sugar industry in the archipelago met those needs.

Still, the sugar industry could not grow beyond certain limits because Mexican silver, the currency of Asian trade, remained the chief object for ships coming to Manila. As late as 1789, export of Philippine sugar did not exceed 30,000 piculs, or 1,898 metric tons, per year, and even in 1819 birds' nests still outranked sugar in value as an export item.[11] Not until the Spaniards altered their economic policy and international demand for sugar picked up could sugar production really expand. These changes began to take place only toward the end of the eighteenth century. By midcentury falling demand for oriental textiles in Mexico and Spain started the Manila galleon traffic on its long decline toward cessation in 1815, a victim of its own anachronistic nature and the Latin American wars of independence.

To compensate for this decline and to put the Philippines at last on an economically independent basis, the government initiated several reforms following the British occupation of Manila (1762-64). Under a series of progressive governors, Spain sought to break the galleon near monopoly of Philippine international commerce, to encourage the growing of local agricultural produce for export, and to keep profits from this new trade in government coffers. In 1785 Governor José Basco y Vargas created la Real Compañía de Filipinas, designed to link private and government capital

to foster a trade within the empire that trespassed even on the hitherto sacrosanct trans-Pacific route. But this endeavor ultimately failed because of a lack of interest and sound management. For example, while foreign merchants were exporting 14,892 tons of sugar between 1786 and 1802, the company shipped only 509 tons. Basco also established in 1781 la Sociedad Economica de Amigos del Pais de Manila to foster a new interest in, and publications about, agricultural crops, but again, lack of sustained concern defeated this project. One of the few tangible results of the society's efforts toward promoting sugar was an 1878 manual by Francisco Gutierrez Creps on the art of growing and producing the sweetener.[12]

The increased international demand for sugar that followed upon the Industrial Revolution stimulated the rise in production. As a result of a petition of la Real Cornpañía de Filipinas, ships of foreign registry began legally to trade in Asian goods at Manila in 1790, thus inaugurating a process of fully opening the port to international commerce by 1834, when the company's charter ended. Initially, the chief beneficiaries of this new policy, as far as the sugar trade was concerned, were Americans who sought new sources of sugar and molasses for their tables and rum distilleries because the British West Indian market had been closed to them following their war of independence. By the mid-1790s, ships from the Atlantic ports, particularly Salem, Massachusetts, frequented Manila; and throughout much of this decade a resident American merchant, John Stuart Ker, acted as broker for U.S. vessels, procuring the cargos of sugar they carried home. As a result of greater sugar consumption among their workers, the English, too, increased their trade and established their first commercial house in Manila in 1809. By the 1820s, England had seven firms at the port, and America one; meanwhile, Americans began consular service in 1817, and the British followed in 1844. These two nations became the chief trading partners of the Philippines and remained so throughout the rest of the nineteenth century.

While figures on sugar export for the first quarter of the nineteenth century remain fragmentary, it appears that sometime in the second half of the 1820s sugar began a climb in output that continued more or less unabated until the end of the nineteenth century (see table 1). The official opening of Manila to world commerce in 1834 did not stimulate this rise; rather, the conclusion of the Napoleonic wars and the subsequent freeing up of shipping, as well as a growing demand for sugar in the United States and England, seem to have been the main causes. In 1836 sugar surpassed rice, abaca, and indigo as chief Philippine export and became one of the mainstays of the economy, a condition that has persisted until recent times.[13]

Table 1. | |

Year | Export (metric tons ) |

Before 1780 | less than 1,898 in any year |

1789 | ca. 2,846 |

1796 | ca. 4,744 |

1786-1802 | avg. 1,058 |

1813 | 949 |

1818 | 911 |

1828 | 7,276 |

1829 | 7,592 |

1831 | 13,432 |

1835 | 11,777 |

Sources: Manuel Buzeta, O.S.A., and Felipe Bravo, O.S.A., Diccionario geográfico, estadístico, histórico de las Islas Filipinas , 2 vols. (Madrid: José de la Peña, 1851), 1:222; Manuel Azcarraga y Palermo, La libertad de comercio en las Islas Filipinas (Madrid: José Noguera, 1871), p. 135; Tomás de Comyn, Estado de las Islas Filipinas en 1810: brevemente descrito (Madrid: Imp. de Repullés, 1820), p. 10; Marîa Lourdes Díaz-Trechuelo Spinola, La Real Compañía de Filipinas (Sevilla: Escuela de Estudios Hispano-Americanos de Sevilla, 1965), p. 269; [Henry Piddington], Remarks on the Philippine Islands and Their Capital, Manila, 1819 to 1822: By an Englishman (Calcutta: Baptist Mission Press, 1828), p. 76; Yslas Filipinas, Estado que manifestan la importación y exportación de esta ciudad en todo el presente año . . . (Manila: n.p., 1818), p. 4; Angel Martinez Cuesta, O.A.R., History of Negros , trans. Alfonso Felix, Jr. (Manila: Historical Conservation Society, 1980), p. 365; Ramon Gonzáles Fernandez and Federico Moreno y Jeréz, Manual del viajero en Filipinas (Manila: Est. tip. de Santo Tomás, 1875), p. 185. | |

Up to 1836, even as foreign trade developed, the manner of making and delivering export-quality sugar changed little from what it had been in the preceding century. Innovation came from China around 1800 with the introduction of stone vertical rollers in place of wooden ones and iron cauldrons (cauas ) in place of earthenware ones; otherwise, the sugar business remained as American supercargo Nathaniel Bowditch described it in 1796 when he purchased a cargo of sugar in Manila for his ship Astrea .[14]

In most Philippine provinces output was small. The sugar was of poor texture and was mainly for local use; nevertheless, a few areas, particularly the Luzon provinces of Pampanga, Bulacan, Pangasinan, and Tondo, earned a good reputation for their product. The former was the most highly regarded for the quality and quantity of its pilon sugar, made from a high

yield, deep red local cane. The success of these regions came in large measure as a result of their proximity to Manila, the center for sugar refining and the only sizable market for consumption of high-grade sugar.

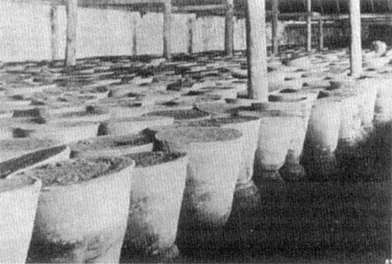

In these provinces, cane, squeezed between stone rollers turned by carabao (water buffalo), released a juice that, when boiled sufficiently in a series of cauldrons, turned into a thick syrup that was poured into conical clay pilones. There, with the aid of stirring and some lime water, the mixture crystallized into a hard substance, a brownish yellow blend of molasses and sugar. Between November and June, traveling agents of refiners purchased pilones, each weighing about 63.5 kilos, from farmer producers and transported them in cascos down the main rivers and streams of Luzon, into Manila Bay, and on to the port area. At small refineries, called farderias , usually operated by Chinese but occasionally by a Spaniard, claying took place. Pilones were broken and sugar separated, the best grade being repacked in new molds. The sugar was then tamped, covered with a thin layer of special clay, and treated with water. As fluid seeped downward, the molasses dripped from a hole in the bottom of the mold into a container below, leaving a purer product, slightly gray on top with a yellow layer underneath. Once the sugar achieved its best color, the pilon was broken and the finest grades separated and dried in the sun; later the finished product was poured into sacks which, when filled, weighed one picul of 63.25 kilos, standard measure of the sugar trade. Merchant refiners stored these bags in warehouses (camarines ) where they awaited sale to foreigners, usually from European and American houses supplying ocean-going vessels. Darker grades could either be reboiled, reclayed, or sold at home, since inhabitants of the Philippines made ample use of various kinds of sugar in their diet.

Another kind of Philippine muscovado, called "mat" sugar, achieved only minor importance in external trade before the 1840s, but found some outlet, mainly to China, Singapore, and Macao. Produced all over the archipelago, but especially in the Visayas, it sold for two-thirds or less the price of pilon sugar, because it was more heavily laden with molasses. In processing mat sugar, cane was passed between wooden rollers and boiled in cauas. Once lime was added to the thickened syrup, final crystallization took place on wooden tables. After drying, the sugar, dark brown in color and resembling a doughy substance, was placed in bayones (buri palm leaf bags of exceptional water resistance) weighing from eighteen to thirty-two kilos each, which were transported to Manila for repackaging and reshipment. Later on, an improved mat sugar garnered a much larger market share as worldwide sugar refining patterns changed, but in the 1830s pilon sugar dominated the trade; moreover, the government took special effort

Table 2. | ||

Price | ||

Year | First Grade | Second Grade |

1796 | 7.00 | 4.50 |

1817 | 6.00 | 5.00 |

1818 | 9.00 | 6.50 |

1820 | 8.00 | — |

1830 | 7. 50 | 6.00 |

1834 | 4.75 | 4.50 |

1836 | 5.25 | — |

Sources: Thomas R. McHale and Mary C. McHale, eds., Early American-Philippine Trade: The Journal of Nathaniel Bowditch in Manila , 1796, Monograph Series, no. 2 (New Haven: Yale University Southeast Asia Studies, 1962), pp. 29-47; Andrew Stuart to Secretary of State James Monroe, May 30, 1817, U.S. Consular Reports, Manila, U.S. National Archives; [Henry Piddington], Remarks on the Philippine Islands and Their Capital, Manila, 1819 to 1822: By an Englishman (Calcutta: Baptist Mission Press, 1828), p. 76; Andrew Stuart to Secretary of State John Q. Adams, April 20, 1820, U.S. Consular Reports, Manila, U.S. National Archives; Ramon González Fernández and Federico Moreno y Jeréz, Manual del viajero en Filipinas (Manila: Est. tip. de Santo Tomás, 1875), p. 238; Centenary of Wise and Company in the Philippines, 1826-1926 (n.p.: n.p., n.d.), p. 101. | ||

to preserve the quality of the product. In 1818, an ordinance passed in Pampanga prohibited adulteration of pilon sugar with darker grades.[15]

Because of market conditions, Philippine export sugar fell in price between 1796 and 1836, as indicated by figures in table 2. Some rise seems to have occurred about the end of the Napoleonic wars, before peacetime shipping fully returned, but, after that, prices did not revert to earlier levels because of changed circumstances in the sugar industry.

Parnpanga

One of the first places the Philippine sugar industry took hold was Pampanga. Leaders of Pampangan society early on agreed to participate in the colonial order and duly benefited from that collaboration. The prehispanic social system was restructured and the population mobilized in the service of the native elite and the Spanish establishment. The contractual labor arrangement that resulted proved adaptable to the needs of the sugar industry as it began to exert an impact on the province.

Archaeological evidence indicates the existence of long prehispanic settlement in Pampanga, and when the Spaniards reached Pampanga, they

Map 6.

Settlement in Early Pampanga

found at least eleven communities along the banks of the Pampanga River system (map 6). The name of the area, indeed, derived from the Capampangan word pangpang meaning "riverbank," and people of the region largely earned their livelihood from that body of water. The river nourished their crops, especially their rice; provided them with fish; and offered them access to interior jungles as well as to Manila Bay and beyond. In the course of their habitation of some of the best grain-producing land in the Philippines, Capampangan developed advanced agricultural techniques, knowledge in the working of brass, and navigational skills that took them to trading emporia of the Malay archipelago. Their use of imported ceramic wares indicated fairly constant commercial intercourse with merchants

originating from the ports of southern China. In addition, Pampanga maintained contact with other parts of the islands through exchange of its excess rice for cotton needed in weaving local cloth. By the late sixteenth century, the delta had become sufficiently populous that Capampangan had moved up feeder streams to Masicu (later called Mexico) and Porac, thus extending their sway onto more elevated, drier portions of the great plain.[16]

Europeans encountered this aggressive and skilled people who dominated a fertile edge of the great forest covering the Central Luzon Plain and began reshaping their social structure and refocusing their economic activities. In 1574 Pampangan warriors were enlisted to defend Manila against depredations of the Chinese pirate Limahong (Lin Feng), thus initiating a tradition of more than three hundred years of military service to the Spanish regime. Subsequently, Spaniards employed their most trusted mercenaries to suppress rebellious natives and riotous Chinese residents, to guard the citadel of Manila, and to make war against the Moros of Mindanao and Sulu. In addition, Pampangan regiments fought overseas, in the Moluccas and Marianas in the seventeenth century and in Vietnam in the nineteenth. Such service brought substantial rewards to their leaders in terms of officers' commissions, even the exalted rank of maestre de campo , and, for a rare few, assignment of an encomienda , a tax-collecting sinecure almost never granted to indios. The most renowned Pampangan soldier of the seventeenth century, Maestre de Campo Don Juan Macapagal, received such an encomienda of three hundred tributes in 1665.[17] Military use of Capampangan provided an early occasion for collaboration between the native elite and the colonial regime, and other opportunities followed.

The Spanish government initially divided wealthy, strategic Pampanga into encomiendas; however, the malfeasance and ineptitude of early Spanish encomenderos made the system unworkable, so the crown moved to institute civil government. Small private encomiendas, like the one to Macapagal, continued to be bestowed until the mid-eighteenth century, but only for recognition of extraordinary service or for maintenance of charitable causes. After the early years of conquest, governance and major tax gathering in the province became the duty of an alcalde mayor (governor), a Spanish appointee of the governor-general, who served in both an executive and a judicial capacity.

Within the province indigenous personnel assumed substantial administrative responsibility because few Spaniards served there. With the disappearance of most encomenderos in the seventeenth century, only an alcalde, parish priests of the Augustinian order, and a handful of soldiers constituted the Spanish government community—in effect the whole of European society—for a law, on the books from the sixteenth century to

1786, prohibited Spaniards from living outside Manila, unless in an official or religious capacity. Spaniards in Pampanga never numbered more than fifty before the second half of the nineteenth century, and control of municipal government passed largely into the hands of gobernadorcillos and cabezas. Under the colonial system, parish priests exercised civil as well as religious authority; nevertheless, priests had to serve in very extensive parishes spread out over many square kilometers containing settlements often difficult to reach. Moreover, between 1773 and 1854 Augustinians did not even hold the Pampangan parishes, because of a clerical dispute with the bishop in Manila. During this time native secular priests represented the clergy, and by 1848 the total number of Iberians in this province of some 140,000 people had sunk to nineteen.[18] A native leadership thus possessed ample opportunity to maintain jurisdiction over the population, collecting taxes, assigning corvee duties, administering justice, and, in general, serving as buffer between the ruling Spaniards and the bulk of the Capampangan.

Mutual self-interest fostered the close collaboration between native leaders and Spaniards during this long era. Spain needed the military and logistical support of the Capampangan, and the local elite took up colonial service in order to continue their prehispanic leadership. In the old Pampangan barangay, authority had resided with the datu, a person exhibiting military, judicial, and administrative ability. The datu presided over a community of lesser datus, freemen (timaua ), and debt slaves in which agricultural land was communally owned and distributed on the basis of need. Members of the community owed labor obligations to the datu in exchange for his leadership, provided he could sustain his authority by virtue of his strength and ability; he could be replaced by another datu if he lost his power.[19]

Sudden intrusion by Spain altered the old basis of authority, and the more ambitious among the datus readily adapted to the new order. Under the colonial regime, loyalty to the government became the main criterion for tenure, and chiefs could perpetuate themselves and their heirs in office merely by delivering goods and services and by not giving offense. In exchange for meeting their quotas, for facilitating native conversion to Catholicism, and for promoting peace and order, Pampangan leaders earned colonial recognition: the inheritable title of cabeza de barangay , head of a group of tribute-paying families. The new position offered its holders numerous advantages, most crucial of which was assurance of continuity. In addition, the cabeza received for his efforts, along with a title, exemption from certain taxes, corvee obligations, and legal liabilities. As a result of administrative reorganization near the beginning of the seventeenth cen-

tury, the new position of gobernadorcillo came into existence, the highest office a native Filipino could aspire to under Spanish colonialism. This official, selected from among and elected by cabezas of a given pueblo (municipality), was ultimately responsible for delivery of the town's tribute. Gobernadorcillos and cabezas in each town of Pampanga became the dominant class in native society, and they and their families became collectively known as the principalia . Principales were addressed as "Don" and "Doña." Although the principalia became a ubiquitous institution in the archipelago, those in Pampanga were especially noted for their reliability and devotion to Spain.[20]

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the principalia converted their political authority into social and economic dominance of Pampanga as well. They used their tax-gathering power and their control of the Spanish system of labor obligation, repartimiento , to reduce the population to share tenants working on lands controlled by the elite. A two-class society, made up of those in charge who monopolized positions and wealth and those who furnished labor for principalia and colonial needs, gradually replaced the more complicated prehispanic society with its various gradations of class, rank, and labor obligations. In each town of the province, a group of families, perhaps a dozen or so, achieved this higher status and perpetuated it with Spanish acquiescence. In exchange for a guaranteed source of goods and services, Spaniards allowed native leaders to control the means of supply, and the population as a whole remained relatively free from colonial interference.

In 1784, perhaps the most astute observer of the techniques by which the elite perpetuated their position, the great reformist governor-general José Basco y Vargas, toured the province and recorded his findings in a decree issued on March 3 at Arayat.[21] In it he noted that farmers could have their implements and draft animals seized as payment for civil debts and that they could be imprisoned for debt during planting, plowing, and harvesting time, even if such incarceration meant loss of their crop. He saw cabezas and former gobernadorcillos avoiding all work on their farms, making others do the labor for no wages, even though legally only those who possessed eight cabalitas (2.24 hectares) of land were exempted from manual work. Principales also rented out land, an illegal practice. Basco observed widespread use of the samacan contract as well. Under this arrangement, a landowner and a laborer (casamac or aparcero ) agreed to farm land on shares, the owner lending seed, food, and money to carry the worker through the season, with repayment coming at harvest time. Basco understood that great abuses occurred under this system because owners charged high interest on loans, forcing their tenants into chronic debt. Moreover,

they loaned tenants rice when the price was cheap and demanded repayment in cash when the rice was dear. By these various methods the elite kept the lower class as the permanent underpaid labor force of the province.

Basco also described the process by which principales acquired control of most land in the province, the pacto de retrovendendo (pacto de retro, or pacto, for short). Through this contract, land was sold for less than its true value, but with the proviso that the seller had the right to repurchase within a specified time limit, with the addition of an interest charge. In essence this arrangement amounted to a way of pawning land to raise cash; however, the system was subject to much abuse, including excessive interest charges. Moneylenders employed the pacto de retro as a means of taking land from poor farmers.

But the pacto de retro was only the latest method for obtaining farmland; other practices had been going on for two centuries. When Spaniards first arrived, they claimed all land in Pampanga for the crown, but because of early datu support, they received large tracts as a reward. The government ceased bestowing such favors after 1626, and all other territory in the province remained royal lands or communal lands to be held by natives in usufruct, rather than in fee simple.[22] In other words, farmers and householders could take up agricultural and residential plots that, theoretically, when vacated became available for reassignment. Such lands could not be bought, sold, or otherwise alienated without court permission. In practice, however, the Pampangan elite acquired real property, purchasing, selling, and renting it out on shares to casamac without ever obtaining a formal right to do so; and they also gained the legal skills to defend their claims in court. Furthermore, they added to their landholdings by picking up, again without official permission, household lots in payment for debts. The principalia thus institutionalized a system of private ownership of land, even though based on faulty legal titles, despite Spanish attempts to maintain a communal system of property control.[23]