Preferred Citation: Metzner, Paul. Crescendo of the Virtuoso: Spectacle, Skill, and Self-Promotion in Paris during the Age of Revolution. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1998 1998. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft438nb2b6/

| Crescendo of the VirtuosoSpectacle, Skill, and Self-Promotion in Paris during the Age of RevolutionPaul MetznerUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · London© 1998 The Regents of the University of California |

To Ann

Preferred Citation: Metzner, Paul. Crescendo of the Virtuoso: Spectacle, Skill, and Self-Promotion in Paris during the Age of Revolution. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1998 1998. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft438nb2b6/

To Ann

Acknowledgments

Every human endeavor is an endeavor of many human beings. A person cannot become an author without other people raising, inspiring, encouraging, educating, training, advising, and assisting that person; similarly, a person’s writing cannot be made into a book without other people expanding, cajoling, massaging, correcting, cutting, prodding, and nudging that writing.

Ann Le Bar, companion and historian, helped me in innumerable ways at every stage in the creation of every part of this book.

Helen Low Metzner and Charles Metzner, my parents, began my instruction in critical thinking and enabled me to pursue my scholarly interest to this distant conclusion.

Stephen Cuffel, Joy Markham, and Ken Wong, friends and originals, gave me inspiration over a long period of time.

John Toews, Scott Lytle, and George Behlmer, professors of history, contributed greatly to whatever virtues I can claim as a historian.

Mark Scholz, friend and historian, assisted me considerably at a late stage in the composition of this book.

Alice Loranth and her staff, led by Motoko Reece, at the Fine Arts and Special Collections Department of the Cleveland Public Library, went out of their way to aid me in my research. Many of the librarians and other staff persons I had contact with at the Library of Congress aided me generously; I would like to mention by name Joan Higbee of the Rare Book and Special Collections Division and Charles Sens of the Performing Arts Division. Leslie Overstreet of the Smithsonian Institution Libraries and Meta Lytle also gave me extra aid with research materials.

The University of Washington Graduate School provided me with a Western European Studies Fellowship that facilitated my spending a full year in Paris conducting research.

I thank these individuals and organizations and all the other relatives, friends, educators, historians, librarians, and organizations who contributed to this book for their help. And I hope that I have helped others in their endeavors as much as they have helped me in mine.

Introduction

The Historical Background

From late-eighteenth-century Paris the world’s first aeronauts arced skyward in gas-filled balloons of their own making above crowds of earthbound onlookers.[1] Then and there human beings began to place themselves in the previously forbidden open air, to successfully defy the consensus of the possible, to fly. Revolutions in the appropriation of space, in the valuation of practical knowledge, and in the projection of the self conditioned these unprecedented ascents of a few bold individuals.

| • | • | • |

Virtuosos are ordinarily taken to be people who exhibit great technical skill in an art, a craft, or any other field of human activity. This study employs a somewhat narrower and more precise definition. Here virtuosos are taken to be people who exhibit their talents in front of an audience, who possess as their principal talent a high degree of technical skill, and who aggrandize themselves in reputation and fortune, principally through the exhibition of their skill.

During the Age of Revolution, individuals with these characteristics appeared in a wide variety of fields, including chess, cooking, crime detection, musical performance, and automaton-building. Their diversity of occupation may have obscured but did not preclude their development of fundamentally similar drives to excel in spectacle-making, technical skill, and self-promotion. More specifically, these virtuosos had a theatrical bent and loved to perform. They sought to find or gather an audience and then to expand it. In so doing, they modified the exercise of their arts to make them more striking to the eye or ear—that is, more spectacular. They presented the marvelous and the outré. They developed large rep-ertoires of techniques. They improved or invented instruments used in their art. They performed often, with rapidity, and from memory. In general they showed their technical skill through the overcoming of difficulties. They advertised their activities in newspapers and on posters. They wrote about themselves or hired or encouraged others to write about them in books and magazines. They solicited for themselves honors, awards, large fees, and other manifestations of social and material advancement. Such were the common characteristics of the virtuosos of the Age of Revolution.

During the Age of Revolution, Paris became the center of a cyclone of virtuosity, as increasing numbers of highly skilled performers arrived from around Europe and the rate of their exhibitions accelerated. Paris was at the same time the center of an anticyclone, as native or naturalized virtuosos flew out from there to tour Europe.

How did it happen that individuals in divergent occupations acquired convergent characteristics? How did it happen that Paris became their focal point? And how did these things happen specifically during the Age of Revolution? The answer in a package is that spectacle-making was encouraged by the proliferation of public spaces, that the cultivation of technical skill was encouraged by the appreciation in the value of practical knowledge, and that self-promotion was encouraged by the dissemination of the self-centered worldview, all of which took place during the eighteenth and first half of the nineteenth centuries throughout the Western world but with particular intensity in Paris.

| • | • | • |

The Age of Revolution is the standard label for a period of Western history that has no standard bracket dates. Here it will refer to the last quarter of the eighteenth and the first half of the nineteenth century, encompassing the American Revolution of 1776–83, the French Revolution of 1789–99, the sporadic revolutions around Europe around 1830, the continent-wide Revolution of 1848, the Industrial Revolution, the Romantic Revolution in the arts, and various other little-studied and unlabeled revolutions.

A revolution in the appropriation of space accompanied the political and economic revolutions. “Space” here means both physical space, defined by location and material characteristics, and social space, defined by common activity of a group of people. For just as “office” may refer to a room, a place in a building, it may also refer to an occupation, a place in society; likewise, “position” may refer to a location or to an occupation. In most countries government is associated with particular buildings in a particular city, but it is more a social than a physical space. Government is the space in which designated people make, execute, and judge adherence to law. In general the political revolutions gave access to this space to many more people, as public officials, as jurors, and as voters. Even more important than this quantitative change was the qualitative, conceptual change: Subjects became citizens and government became self-government. Areas formerly ruled from outside became independent: The United States gained independence from Great Britain in 1783, Norway from Denmark in 1814,[2] Greece from Turkey in 1829, Belgium from the Netherlands in 1830, and both Hungary and northern Italy from Austria temporarily in 1848–49 and permanently in the 1860s. Elected legislative and consultative bodies sprang into existence or, where such bodies already existed, they acquired real power. Kings and queens continued to rule in almost all the countries of Europe, but many of them now ruled over constitutional or limited rather than absolute monarchies. Thus, during the Age of Revolution more and more people could feel that their government was more and more collectively theirs. Put another way, during the Age of Revolution a large number of governments were wrested from the private domains of family dynasties and converted into public spaces.

This happened in France, which went through a whole series of political revolutions. These followed a long series of kings, many of them named Louis, who ruled during a period afterward termed the Old Regime, extending back from 1789 into the Middle Ages. In 1789 broke out the first of the political revolutions, known variously as the French Revolution, the Great French Revolution, the Great Revolution, or simply the Revolution. It started rather peacefully, but gradually, from one representative assembly to the next—the Estates General, the National Assembly, the Legislative Assembly, and the National Convention—it became more radical and violent. The successive assemblies progressively restricted the powers of King Louis XVI until finally the National Convention abolished the monarchy, put the deposed king on trial, and executed him. Shortly thereafter, the Committee of Public Safety, a group of twelve Convention representatives led by Maximilien Robespierre, took control of France and from June 1793 to July 1794 waged a Reign of Terror against its real and perceived enemies, around seventeen thousand of whom were executed by summary justice.[3] Other Convention representatives finally overthrew this brutally effective regime and drew up a new constitution that resulted in a corrupt, ineffective regime called the Directory, after the name of the five-member executive council at its head, which governed during the last four years of the Revolution, from 1795 through 1799.

The revolutionaries made government a public space and then used the space for public spectacles. Discussion in the representative assemblies became oratorical fireworks. Votes became judgments executed by the guillotine, set up in large city squares for the accommodation of large audiences. Fêtes and processions decreed by the assemblies flooded the newly laid-out parks and boulevards of Paris with hundreds of thousands of people celebrating a funeral, an anniversary, a religious belief, a military victory, or a new sense of nationhood.

The revolutionaries also opened up many public spaces in the economy. The Old Regime had had a labyrinth of regulations protecting established patterns of economic activity but obstructing economic development. Most trades, for example the food service trades of cookery, butchery, and patisserie, operated under the guild system, a rigid system of laws, rules, and traditions according to which one could open a pastry shop only after becoming a master pastrycook, one could become a master only after working for several years as a journeyman, and one could become a journeyman only after successfully completing a years-long training program as an apprentice. Impresarios of theaters and publishers of books, periodicals, and newspapers had to have a license from the government, which issued only a limited number of them and then censored the limited output of those few licensees. A network of internal customs barriers had grown up over the centuries, so that to import goods from the French provinces into Paris, for example, one had to pay a duty at the city gate where one entered. The revolutionaries abolished the guild system, so that anyone could open any business; they abolished the licensing and censorship of organs of communication, so that anyone could write or say anything in public as well as in private; and they abolished all internal tariffs, so that any product could be moved freely within the country.[4]

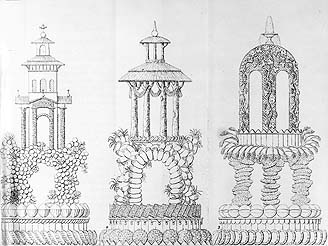

Cafés and restaurants, theaters and exhibition halls, concert series and serial publications are some of the sorts of public spaces that perforated the private quarters of Paris during the Revolution. Taking advantage of all the new public spaces, the practitioners of various arts and crafts became performers and used these spaces as settings for the playing of multiple simultaneous blindfold chess games, for the presentation of huge decorative sugar-sculpture centerpieces, for the exposure of the underworld of crime, for the performance of impossibly difficult pieces of music, and for the exhibition of mechanical marvels that imitated human beings in appearance and movement. In sum, they used these spaces to stage an expanding spectrum of spectacles.

A revolution in the valuation of practical knowledge accompanied the social and economic revolutions. In broad terms, the social revolution of late-eighteenth- and early-to-mid-nineteenth-century Western Europe consisted of the slow but pervasive change from aristocratic society to bourgeois society. In aristocratic society one’s place was largely determined by the circumstances of one’s birth: the social class of the family into which one was born, the occupation of the father of the family, the place of one’s birth, the order of one’s birth in relation to siblings, one’s sex. In bourgeois society what mattered most was the size of one’s assets. As a result of this difference, the two societies also differed in the opportunity they offered to individuals to change situations. In the former society one’s situation had been substantially fixed, while in the latter society one had the potential for considerable social mobility. Money was of course the principal means of social mobility in bourgeois society, but one could acquire enough of it to move upward in any of several ways. One could inherit it, earn it in business as an entrepreneur, or earn it in business or government as a professional—that is, as someone with specialized practical knowledge.

The abolition of the guild system, of the licensing and censorship of the organs of communication, and of internal tariffs, although they laid the foundations of the laissez-faire economic system, constituted a legal rather than an economic revolution. The real engine of economic development in the Age of Revolution was industrialization, the conversion from animal power to machine power in the production of goods. Making this conversion required technological innovations and the commercial reproduction of those technological innovations. In reproduction France lagged somewhat behind Great Britain and the United States, but in innovation France led. French science was second to none for at least the first half of the Age of Revolution. In Paris, Lavoisier founded modern chemistry; Champollion deciphered Egyptian hieroglyphics; Foucault measured the speed of light; Buffon, Lacépède, Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, and Cuvier headed the advance of biology; and Monge, Laplace, Lagrange, and Fourier made innovative applications of mathematics to hydraulics, astronomy, thermodynamics, and other branches of physics. The French also made innovative applications of new knowledge to technology. The balloon ascents of the late eighteenth century arose out of the new chemistry, for example. But while the first gas light was constructed by Philippe Lebon, it was the British who made gas lighting commercially successful. And while the French marquis de Jouffroy d’Abbans built and demonstrated the first operational steamboat as early as 1783, the year of the first manned balloon ascent, it was the American Robert Fulton who built the first commercially successful steamboat, two decades later.

The government of Napoleon Bonaparte was almost as much a technocracy as a military dictatorship. General Bonaparte overthrew the Directory in a coup d’état in 1799, initially calling his regime the Consulate and himself first consul, five years later proclaiming France an empire and himself Emperor Napoleon. As chief of state, he conducted a long series of military campaigns in which he conquered many European countries and intimidated most of the rest into signing treaties favorable to France. But he had been trained as an artillery expert and had almost as much respect for mathematics as he had for tactics. He conducted a domestic modernization campaign, encouraging industry, founding technical schools, and appointing scientists and technical experts as well as generals to head his ministries.

The reorganization of society on the basis of wealth rather than birth, industrialization, and Napoleon’s experiment in technocracy all contributed to the increasing value of practical knowledge in French society. Inventors attracted great celebrity. The École Polytechnique, the national engineering school founded during the Revolution, quickly became the most prestigious school in France and the model for a series of “Grandes Écoles.” Practitioners of every art and craft imagined themselves mechanicians, tinkering with the tools of their trade. Or they imagined themselves authors, publishing handbooks, manuals, encyclopedias, and repertoires of techniques. Or they imagined themselves performers, making agility the basis of a new theatricality. In sum, the appreciation in the value of practical knowledge encouraged individuals to strive to master their world through the cultivation and demonstration of technical skill.

A revolution in the projection of the self accompanied the intellectual and economic revolutions. The Enlightenment is the name of a radiation of ideas that illuminated France and other parts of the Western world in the eighteenth century, more brightly in the second half than in the first. Among the leading lights of the French constellation were Diderot, Rousseau, Montesquieu, Voltaire, La Mettrie, and Condorcet. In general they opposed organized religion and advocated that individuals formulate their own creeds; hence, they were anti-priest but not for the most part antireligious, although they undoubtedly contributed to the secularization of French society. They championed tolerance for dissenting beliefs and opinions, education for a larger proportion of the population and a less dogmatic curriculum, a more equitable legal system with more rights for commoners and fewer privileges for aristocrats and clerics, and the free exchange of ideas. They strongly believed in and encouraged progress in the arts, sciences, and crafts, and they preached the dignity of all useful labor, whether spiritual, mental, or physical.

Partly in reaction to the Enlightenment, another radiation of ideas be-gan in the second half of the eighteenth century but did not reach full intensity until the first half of the nineteenth. If the ideas of Romanticism consisted more of heat than of light, this did not make them any less important. No significant improvements could have occurred in French or Western society without ardent supporters of such improvements. Rousseau was the leading early- or pre-Romantic in France, where, later, Hugo in literature, Berlioz in music, and Delacroix in painting figured among the most productive generators of Romanticism, which issued from the fine arts. Romanticism propagated among a large number of individuals the idea that one’s own life and activities have great value, and that the more energy and feeling one puts into one’s life and activities the better; and it propagated in society at large the idea that people of accomplishment are society’s real aristocrats and that a genius is a demigod.

Both the Enlightenment and Romanticism, through their emphasis on the value of personal achievement at the expense of the values of family tradition and social hierarchy, contributed to the democratic revolution, to the industrial revolution, to the bourgeois revolution, and most of all to the new self-centered worldview. Before the Age of Revolution, most people’s social worldview had at its center the king or the pope, the local lord or priest, or the head of one’s family. One saw oneself more or less distant from, dependent on, subordinate to—in short, revolving around—that center. But during the Age of Revolution many people began to believe that self-fulfillment rather than obedience to another was their proper function, and to see themselves at the center of their world.

The transformation of the economy worked in conjunction with intellectual movements to spread the new self-centered worldview. Handle in hand with the industrial revolution went an agricultural revolution. In the second half of the eighteenth century, for the first time in history, a human society succeeded in increasing the yield of its food crops to the point of making itself immune from famine for the foreseeable future. Over the past two hundred years there has always been sufficient food in the Western world to feed the entire population; what starvation there has been has resulted from unequal distribution. Similarly, there has always been sufficient means to distribute the food, only occasionally unequal will. Concentration of land ownership, introduction of new crops and new winter crops, rotation of different crops on the same plot of land, specialization in cash crops, increased fertilization of crops, selective breed-ing of livestock, and of course new machinery, all contributed to the agricultural revolution. With more food being produced by fewer people, the “surplus labor” of the countryside migrated to the cities to tend the engines of industry rather than the animals of agriculture, thus contributing to industrialization. More people could also be fed, so many more in fact that the population exploded. The population of Europe expanded from 105 million in 1700 to 120 million in 1750 to 180 million in 1800 to 265 million in 1850, increases of 15 million, 60 million, and 85 million in successive half-centuries. The population of France expanded slightly less rapidly, from 19 million in 1700 to 22 million in 1750 to 27 million in 1800 to 35 million in 1850, increases of 3 million, 5 million, and 8 million in successive half-centuries. The real explosion took place in the largest cities, such as Paris, which only grew from 530,000 in 1700 to 550,000 in 1800, or less than 5 percent in a full century, but then grew from 550,000 in 1800 to 1,300,000 in 1851, or more than 100 percent in just half a century.[5]

More people, people living closer together, and a rising standard of living, if not yet for the majority then at least for a substantial minority, brought about a phenomenal intensification of communication. Books, magazines, newspapers, broadsheets, engravings, plays, concerts, exhibitions, and expositions rained down, saturating the public with the ideas of the Enlightenment and Romanticism. The swollen media, press and theater, bearing a new message, the self-centered worldview, produced waves of advertising, upstaging, and autobiography in a whirlpool of self-promotion.

Like industrialization, the conversion to bourgeois society, and the radiation of new ideas, democratization in France took place over a long period of time in France. These were revolutions not in the sense of rapid change but in the sense of radical change. The transition to democracy that began with the Revolution of 1789 took most of a century to complete. In 1814 the Great Powers of Europe, having deposed Napoleon, restored the old monarchy in France, with Louis XVIII as the first king of this Restoration. But the monarchy was now a constitutional monarchy as in Britain, not an absolute monarchy as it had been, or as still existed in Austria, Prussia, and Russia. When King Charles X, who succeeded to the throne in 1824, tried to make the monarchy absolute again he was overthrown in a popular revolution, called the Revolution of 1830 or the July Revolution. That event marked the end of the Restoration and the beginning of the July Monarchy. The July Monarchy had only one monarch, King Louis-Philippe, a close relative of the preceding kings but quite reconciled to constitutional government. However, his regime favored the interests of the wealthy, the only segment of the population with the right to vote. Yet another revolution, the Revolution of 1848, overthrew him and led to the founding of the Second Republic, in which the government was to be elected by universal men’s suffrage. This enlarged electorate chose as president Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, nephew of Napoleon I, who in 1851 reestablished authoritarian government in a coup d’état, calling his regime the Second Empire and himself Emperor Napoleon III. Only in 1871 did France become a democracy more or less permanently, upon the founding of the Third Republic. Like the revolution in politics, the three revolutions that are examined in this study—the revolution in the appropriation of space, the revolution in the valuation of practical knowledge, and the revolution in the projection of the self—were prolonged but profound.

| • | • | • |

The present study elaborates the conventional concept of the virtuoso, most commonly applied to musicians, into a more carefully defined type, and applies it to individuals in a wide variety of occupations.[6] Doing this enables us to perceive patterns that histories of a single art, a single aspect of society, or a single revolution do not show. We discover in the same place at around the same time but in very different social spheres common behaviors: spectacle-making, the cultivation of technical skill, self-promotion. We discover in association with the various political, economic, social, and intellectual revolutions in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Western society common developments: a proliferation of public spaces, an appreciation in the value of practical knowledge, a dissemination of the self-centered worldview. Moving back and forth across the conventional boundaries that have been laid down between disciplines, we discover a more variegated and verisimilar texture of life than histories that respect those boundaries show us. We see an original picture of the Age of Revolution.

History that is deeply interdisciplinary is not common, but it does exist. Carl E. Schorske’s Fin-de-siècle Vienna (1980), which treats literature, architecture and urban design, politics, psychology, painting, and music as they developed in Vienna around the turn of the twentieth century, is a model of interdisciplinary history. Professor Schorske gives this explanation of his method:

Like Schorske’s, the present history proceeds from one post-hole to the next. It takes up chess in chapter 1, cooking in chapter 2, crime detection in chapter 3, musical performance in chapter 4, and automaton-building in chapter 5. The focus in each chapter is on one or a few of the leading practitioners and their places in the history of their fields. Schorske’s explanation continues:The conviction that, to maintain the analytic vitality of intellectual history as a field, I would have to approach it by a kind of post-holing, examining each area of the field in its own terms, determined the strategy of my inquiry. Hence these studies took form from separate research forays into distinct branches of cultural activity—first literature, then city planning, then the plastic arts, and so on.

He fulfills his implied promise, reconstructing in convincing fashion his subjects’ common ground. He does this in the same chapters that consider “distinct branches of cultural activity,” while the present history uses a separate set of chapters to give an account of a “shared social experience.” Chapter 6 situates the virtuosos’ spectacle-making in the context of the proliferation of public spaces; chapter 7, their cultivation of technical skill in the context of the appreciation in the value of practical knowledge; and chapter 8, their self-promotion in the context of the dissemination of the self-centered worldview. All together then, the present history consists of a set of five diachronic essays that emphasize “the autonomy of fields and their internal changes” and another set of three essays that cross the boundaries between fields in order to establish the “synchronic relations among them.” Each of the eight essays elaborates its own individual thesis and also serves the aims of the study as a whole.But had I attended only to the autonomy of fields and their internal changes, the synchronic relations among them might have been lost. The fertile ground of the cultural elements, and the basis of their cohesion, was a shared social experience in the broadest sense.[7]

There are three principal aims of the study as a whole. The first is to show that a variety of prominent individuals working at around the same time but in different fields had certain striking similarities, justifying the categorization of them under one rubric: virtuosos.

The second aim is to suggest that Paris during the Age of Revolution was exceptionally rich in virtuosity. Other individuals with the same characteristics have of course worked in other places at other times. Their numbers, their loci, and how they may have differed from the subjects of this study would require other studies to determine. Since “rich” is a comparative term and since studies of virtuosity in other historical locations are lacking—in short, since there are no good bases for comparison—this study can only hypothesize that Paris during the Age of Revolution was unusually rich in virtuosity.

The third aim is to connect the common characteristics of the virtuosos studied here to the social and cultural tendencies of the historical milieu that favored their appearance. More specifically, the aim is to show that certain developments permeating Paris during the Age of Revolution nurtured what appears, at least, to have been an unusual growth of virtuosity. Again, nothing more than a hypothesis can be advanced. It is difficult to imagine what would constitute proof of connections between such phenomena as are the subject of this study. Yet to refuse to hypothesize about them would be to sacrifice a large part of the interest of it. Whence came the contemporaneous and strikingly similar shoots of virtuosity, if not out of a common ground of social and cultural elements?

| • | • | • |

The temptation is great, greater than in the case of many other historical subjects, to judge the virtuosos either heroes or villains. A certain ambivalence is associated with the very words “virtuoso” and “virtuosity” and their French cognates virtuose and virtuosité. These words all derive from the Italian word virtù, or rather from a particular Italian Renaissance meaning of virtù: “will power, moral energy, a bold and informed resoluteness of purpose, overcoming every difficulty” (forza d’animo, energia morale, decisione coraggiosa e cosciente per cui l’uomo persegue lo scopo che si è proposto, superando ogni difficoltà). Virtù could also mean, of course, “disposition to do good” (disposizione a fare il bene).[8] Similarly, “virtue” in modern English and vertu in modern French can mean either “effective force or power” or “goodness; conformity to standard morality.” [9] Because of the moral and aesthetic ambiguity of their activities, inherent in the word used to characterize them, the virtuosos of the Age of Revolution inspire in their observers now attraction, now aversion, now both simultaneously.

As human beings observing other human beings in another time, place, or culture, our first task is to try to understand what the values of those others are. We should not judge before we understand what we are judging. The first task of a historian is to try simply to describe the people of another period of history and their culture.

Of course we frequently cannot avoid reacting favorably or unfavorably to what we see almost as soon as we see it. But when we have a strong reaction we should ask ourselves why that is. When we are observing a distant world, we often react favorably or unfavorably to something in it because that something reminds us, usually unconsciously, of something in the world immediately around us for which we have a well-established preference or aversion. In other words, we feel the same emotion when we see a familiar color, shape, or texture on a strange object as when we see it on a familiar object. Turning our gaze from our own world to the distant world of Paris in the Age of Revolution, we will repeatedly see familiar characteristics and a familiar virtue.

Notes

All translations of quotations from other languages into English are the author’s unless otherwise noted.

1. The first manned balloon flight took place over Paris on 15 October 1783, when Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier ascended in a balloon made by Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier. Pilâtre de Rozier later ascended in balloons of his own making, as did several other French aeronauts. Henry Dale, Early Flying Machines (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), pp. 12–18.

2. In the process of gaining independence from Denmark, Norway, as “a free, independent, and indivisible kingdom,” was united with Sweden under the same king; only in 1905 did it get its own king.

3. Historians differ somewhat in their dating of the beginning of the Reign of Terror; the beginning date used here is taken from Jean Tulard, Jean-François Fayard, and Alfred Fierro, Histoire et dictionnaire de la Révolution française, 1789–1799 (Paris: Laffont, 1987), pp. 1113–14. The authoritative body count, 16,594, is that of Donald Greer, The Incidence of the Terror during the French Revolution: A Statistical Interpretation (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1935), p. 26.

4. Regimes subsequent to the Revolution revived licensing and censorship with varying degrees of restrictiveness, but the guild system and the internal customs network were dead.

5. For population figures for Europe: Colin McEvedy and Richard Jones, Atlas of World Population History (Harmondsworth, Eng.: Penguin, 1978), p. 18. For population figures for France: R. R. Palmer and Joel Colton, A History of the Modern World (New York: Knopf, 1984), p. 966; Gordon Wright, France in Modern Times (New York: Norton, 1981), pp. 14, 179; B. R. Mitchell, European Historical Statistics (New York: Facts on File, 1975), p. 30. For population figures for Paris: Tertius Chandler and Gerald Fox, Three Thousand Years of Urban Growth (New York: Academic Press, 1974), pp. 17–20; Louis Chevalier, Laboring Classes and Dangerous Classes in Paris During the First Half of the Nineteenth Century, trans. Frank Jellinek (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1973), pp. 181–82.

6. This procedure is modeled on Max Weber’s methodology of the “ideal type.” For an explanation of this methodology: Max Weber, “‘Objectivity’ in Social Science and Social Policy,” in Max Weber, The Methodology of the Social Sciences, trans. and ed. Edward A. Shils and Henry A. Finch (New York: Free Press, 1949). For an example of its use: Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, trans. Talcott Parsons (New York: Scribner, 1958).

7. Carl E. Schorske, Fin-de-siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture (New York: Vintage, 1981), pp. xxii–xxiii.

8. Nicola Zingarelli, Il Nuovo Zingarelli: Vocabolario della lingua italiana (Bologna: Zanichelli, 1988), p. 2155. One can see very clearly in Benvenuto Cellini how virtù in the Italian Renaissance sense of “will power” may have evolved into “virtuoso” in the modern sense (in English, French, German, and Italian) of “a person with masterly technique or skill in the arts.” In his autobiography, Cellini frequently uses the word virtù to mean “will power,” and the word virtuoso to mean “a person with will power.” He also frequently shows himself exercising great virtù in this sense, advancing his own claim to be a Renaissance virtuoso. He exercised this virtù especially in his artistic practice, where his acquisition of great technical skill in goldsmithery and sculpture made him a virtuoso in the modern sense.

9. William Morris, ed., The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (New York: American Heritage, 1969), p. 1432; A. Rey and J. Rey-Debove, eds., Le Petit Robert: Dictionnaire alphabétique et analogique de la langue française (Paris: Le Robert, 1988), p. 2084.

1. Some Models of Excellence

Chess, cooking, crime detection, musical performance, and automaton-building are five arts—as we may call them, lacking a better generic term—whose histories all intersected at Paris during the Age of Revolution. Specifically, the histories of these arts each presented at least one outstanding master, one model of excellence, at that particular place and time. The observation of this striking convergence serves as the point of departure for the present study. The first half of the study will sketch the careers of this cluster of standouts each in turn and place them historically, but not so much in the context of Paris during the Age of Revolution as in the context of the evolution of their respective arts. It begins with some chess players.

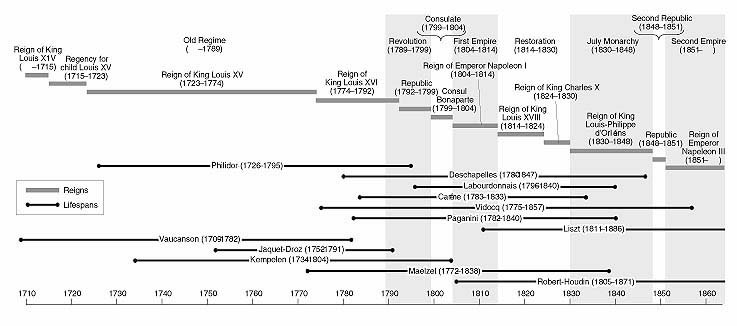

Lifespans of the subjects of this study

1. Philidor and the Café de la Régence Chess Masters

| • | • | • |

§ 1. The Second Career of François-André Danican Philidor (1726–1795) as a Chess Player

Rain or shine, it is my regular habit every day about five to go and take a walk around the Palais-Royal.…If the weather is too cold or rainy, I take shelter in the Café de la Régence, where I entertain myself by watching chess being played. Paris is the world center, and this café is the Paris center, for the finest skill at this game. It is there that one sees the clash of the profound Légal, the subtle Philidor, the staunch Mayot; that one sees the most surprising combinations and hears the most stupid remarks. For although one may be a wit and a great chess player, like Légal, one may also be a great chess player and a fool, like Foubert and Mayot.[1]

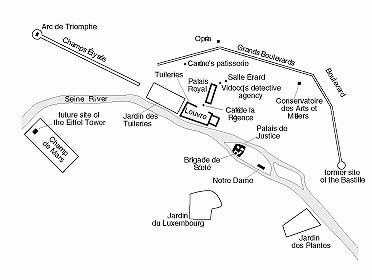

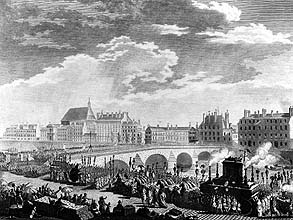

Thus begins Denis Diderot’s famous work of indeterminate genre, Le Neveu de Rameau (Rameau’s Nephew, 1760s). Whether considered a work of fiction or nonfiction, its opening passage certainly contains much that is true to life. The Café de la Régence was a real café, established in 1681 and later renamed for the Regency period, from 1715 through 1723, when it won great popularity. It was in fact widely regarded as the site of the best chess-playing in Europe, if not the world, from Philidor’s rise to prominence around 1740 until Labourdonnais’s death in 1840. And Diderot did indeed frequent the place.[2]

Several others among the philosophes, those eighteenth-century intellectuals who led the movement known as the Enlightenment, also entertained themselves there. Montesquieu perhaps, Voltaire and Benjamin Franklin very likely, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau most definitely paid regular visits during one period or another in their lives. Spectators assembled there in crowds after Rousseau became famous and the police had to station guards at the door to control them. For their part, the philosophes did not go to the Café de la Régence only to watch or to converse; they went to play chess.[3]

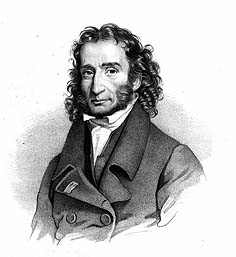

Portrait of Philidor. Courtesy of the John G. White Collection, Special Collections, Cleveland Public Library. Photograph by the Cleveland Public Library Photoduplication Service

The “royal game” had been accepted for hundreds of years at face value, as just a game, an amusement, a diversion. The few who ascribed a deeper significance to it considered it a symbolic representation of war, an activity generally associated with the aristocracy, and the game itself was also generally thought to belong to the aristocracy. In the eighteenth century, however, intellectuals took an increasing interest in chess, so that by the end of the century it had become as much or even more their game than the nobility’s. The philosophes, who had a collective reputation for questioning everything, began to wonder whether there might be something in the game other than mere amusement or symbolic war.

Diderot appears to have been undecided on the matter, to judge from Le Neveu de Rameau. The Encyclopédie (1751–80), the great literary monument of the Enlightenment edited by Diderot and his friend d’Alembert, expresses the same uncertainty in its article “Échecs” (Chess). The author of the article, the chevalier de Jaucourt, concedes that some people,

Nevertheless, both Jaucourt and his editors must have felt that the game had some significance beyond its obvious entertainment value, otherwise why devote an article to it at all, and why admire people who excel at it, such as Philidor?struck by the fact that chance has no part in this game, and that skill alone brings victory, have regarded good chess players as endowed with superior minds; but if this reasoning is correct, how is it that one sees so many mediocre thinkers, indeed even a few near-imbeciles, excel at the game, while geniuses of all sorts have not been able to reach the level of a mediocre player?

We have had at Paris a young man aged eighteen, who used to play two games of chess at once without looking at the boards, beating two players of better than average ability, to each of whom he could only give odds of a knight when playing with sight of the board, although he himself was a player of the first rank. To this feat may be added something that we witnessed with our own eyes: In the middle of one of these matches, an illegal move was deliberately made; after a rather large number of subsequent moves, he recognized the error and had the piece put back where it belonged. This young man is a M. Philidor; he is the son of a musician of some renown; he is himself a great musician, and perhaps the best player of Polish checkers there ever was or ever will be. This is one of the most extraordinary examples of the power of memory and imagination.[4]

The German philosopher and mathematician Leibniz, another representative of the Enlightenment, unhesitatingly recommended chess: “I strongly approve the study of games of reason, not for their own sake, but because they help to perfect the art of thinking.” [5] Thus, unlike Jaucourt, Leibniz did expect good chess players to be good thinkers. Philidor, perhaps misunderstanding him, wrote in the preface to his chess treatise: “I believe I have improved the theory of a game that many famous authors, such as Leibniz, consider a science.” [6]

Others believed that chess could teach morality. In a letter, Diderot drew attention to the chess master Légal’s maxim that when a misplay occurs, the rectification “in doubtful cases should always be against the player who might have been in bad faith.” Diderot did not credit the game as much as the player, however: “What is so frivolous that it cannot inspire a few serious reflections?” [7] While living in Paris, the didactic autodidact Benjamin Franklin composed a short essay entitled “The Morals of Chess” (1779). He asserted therein that playing chess was “not merely an idle amusement” but a constructive activity that fostered the virtues of foresight, circumspection, caution, and perseverance.[8]

Le Neveu de Rameau first appeared in print not in French but in German, in a translation made by the ennobled literary giant Goethe, who did not really belong to the Enlightenment, although his lifetime overlapped those of most of the philosophes. In one of his early dramas, he had a character say of chess that “the game is the touchstone of the intellect.” [9] These eighteenth-century intellectuals, whatever the diversity of their views on chess, all seem to have considered it more than just a game. Perhaps they could have reached agreement on the limited conclusion advanced by the salon aphorist Chamfort: “A good heart is not sufficient to play chess.” [10]

| • | • | • |

François-André Danican Philidor had two careers. His first career, in music, during which he played chess as a second occupation, accorded well with Old Regime French society. But when tastes changed and his career in music began a decrescendo, he composed a second career out of chess, which struck Old Regime society as a dissonance.

The Danican family acquired the name Philidor when François-André’s great-grandfather or great-uncle moved to Paris in the early seventeenth century and joined the orchestra of the French court, replacing a distinguished Italian oboist named Filidori. King Louis XIII, after hearing his new oboist play, is supposed to have remarked in delight: “I have found a second Filidori.” The Danicans adopted the royal compliment as a sort of title and subsequently supplied many musicians to the kings of France. François-André grew up in the ambience of the royal chapel, where he served as a page de la musique, studying music and singing in the choir. At the age of eleven he composed a motet that was performed in the cha-pel before Louis XV, who rewarded and encouraged him. The precocious composer wrote several more motets before he turned fourteen, when he retired from his official post. At that point he became self-employed, copying music and giving private lessons. He continued to produce motets and to have them performed at Versailles.[11]

Meanwhile, Philidor had discovered chess. His eldest son, who started to write his biography but did not get very far, passed along this anecdote:

According to Philidor’s son, he rapidly surpassed all the other musicians. After he left the royal chapel in 1740, he began to frequent the Café de la Régence. At the time, according to Philidor himself, chess enthusiasts played in many of the cafés of Paris. But M. de Kermur, sire de Légal, held court at the Régence.[12]At the age of six, he was allowed to join the children of Louis XV’s chapel. The musicians, while waiting for the king to arrive for [daily] mass, customarily played chess on a long table that was inlaid with six checkerboards. Philidor used to entertain himself by watching the games, to which he gave his entire attention. He had scarcely turned ten when one day an old musician, having arrived before any of the other players, complained to him of their lateness and expressed annoyance at not being able to begin a game. Hesitantly, Philidor offered to play; the musician responded first by laughing and then by accepting. When the game began the musician’s disdain for his young opponent soon gave way to astonishment. The game progressed, and it was not long before irritation appeared, quickly swelling to such proportions that the child, fearing the consequences of wounded pride, began to watch the door. He pursued his successful course of play, edged imperceptibly toward the end of the bench, and fled suddenly after advancing the winning piece and crying “Checkmate!” The old musician was left to curse his leaden legs and swallow his rage.

Born around the turn of the eighteenth century in Brittany, Légal was the founder of the Café de la Régence dynasty. As we have seen, the narrator of Le Neveu de Rameau refers to him as “a wit and a great chess player”; the character “Rameau’s nephew” calls him, somewhat indirectly, a chess genius. For countless years he sat in the same chair and wore the same green coat, taking large quantities of snuff and attracting a crowd with his equally brilliant conversation and combinations. He had already established his reputation as the best in France when Philidor first walked into the Régence in 1740, and he continued playing into the 1780s, his own eighties, without ever having to acknowledge a superior, although he lost at least one match. Philidor persisted as Légal’s chess student for three years, during the course of which he increasingly neglected and finally lost his own music students. But by the end of this period he could hold his own against his master without having to accept odds. He also learned about blindfold play from Légal, who, however, apparently did not attempt it more than once or twice himself.[13] As the Encyclopédie attests, Philidor could soon play two blindfold games simultaneously.

Philidor traveled to the Netherlands in 1745 with the father of a child-prodigy harpsichordist in preparation for a series of concerts to be given there. The harpsichordist died suddenly, however, obviously putting an end to the whole project. But Philidor stayed on in the Netherlands anyway, playing chess and Polish checkers for stakes and giving chess lessons for a fee. Not only the Dutch supported him in this way; so too did some English army officers—noblemen, of course—who were on the Continent to play out the intricate endgame of the War of the Austrian Succession. It was undoubtedly the latter’s encouragement that prompted Philidor to go to England in 1747.[14]

In London, Philidor boosted his international reputation by winning two important matches. He defeated Sir Abraham Janssen, the top-rated English player, three games to one, and Philippe Stamma, a native of Syria and author of a well-known chess treatise published a decade earlier, eight games to one, with one draw. In 1748, Philidor returned to the Netherlands, where he composed his own chess treatise, Analyse du jeu des échecs (Analysis of the Game of Chess), and then in 1749 went back to London, where he published it. Again he bested Stamma, this time in the bookstalls. The number of copies of the Analyse that sold over the course of the next two centuries cannot even be estimated. All told, it has appeared in at least one hundred editions, in at least ten languages. And it sold well immediately, probably in large part because of its novel attempt to build a bridge between general principles of good play and the bare record of moves made in model games. Like previous writers on chess, Philidor provided both abstract theory and records of games, but unlike them he also annotated the records at key points in the games, telling his readers which possible moves at those junctures he judged good and which bad, and on the basis of what principles. In another break with tradition his book emphasized good use of one’s pawns, pieces relatively neglected in the royal game until then. In a revolutionary maxim Philidor wrote that pawns “are the soul of chess.” [15]

After perhaps two years’ residence in England, Philidor left to visit Germany, at that time an irregular checkerboard of more than a hundred independent principalities. Frederick the Great of Prussia welcomed him to Potsdam and observed some of his games, but the martial king, although a chess player, did not himself venture into the field against such a formidable adversary. It was there in 1751 that Philidor’s first-known three-game simultaneous blindfold exhibition took place. The mathematician Leonhard Euler, in nearby Berlin, unfortunately missed the entire visit, although he mentioned it in a letter, calling Philidor a great chess player and thereby giving posterity some idea of the latter’s international fame. Besides Frederick, at least two other German princes castled Philidor before he returned to England.[16]

He remained in England until 1754, when he at last went home to Paris, which, to the best of our knowledge, he had not seen in nine years. Although Philidor played a lot of chess during this long vagabondage, he did not entirely neglect music. We recall that he had set out from Paris to assist with a musical tour that ended before it started. The fact that he never played an instrument and that he apparently ceased singing after he left the royal chapel raises the question of what his role in the tour was supposed to have been. He may have been asked to do some arranging. Whatever the original plan, nothing indicates that he had anything to do with music while in the Netherlands. In Prussia, he was reported to have taken some lessons in counterpoint and studied the works of German composers. In England, he did some composition of his own. His son said that he managed to have one of his pieces performed in London in 1753, and that “the famous Handel gave it a benevolent welcome and found its choruses well-constructed.” [17] That same year he placed this curious notice in the 9 December issue of the London Public Advertiser:

Mr. Philidor begs leave to acquaint the public, that in order to justify himself of the calumny spread about town, that he was not the author of the Latin Music he gave last year, as likewise to convince the world that the Art of Music has been at all times his constant study and application, and Chess only his diversion, he has undertaken to set an Ode to Music, in praise of harmony, wrote by the celebrated Mr. Congreve.[18]

This public statement tells us not how Philidor actually lived but rather how he saw himself, or how he wanted to be seen, in his society. And it probably says as much about Western society in the mideighteenth century as it does about Philidor as an individual within that society. Scarcity of evidence prevents us from being able to make an independent assessment of the relative importance to Philidor of chess and music, in terms of, for example, hours spent or income derived, during his nine years as a knight errant. It is quite likely that Philidor supported himself, even comfortably, playing chess. It is also likely that chess occupied a good part of his waking day for large portions of that period. But whether or not it was in some objective sense his occupation, he did not consider it such. Some intellectuals might have gone beyond considering chess merely a diversion, to the point of considering it a useful or instructive diversion, but almost no one in the Western world could yet conceive of it as an occupation.

Philidor may also have earned money during those nine restless years by giving music lessons, copying music, or composing. But certainly chess more than music provided him with adventures, opened doors for him, and enabled him to see the world and learn about life, including musical life, outside of France; perhaps chess even supported further musical study and paid his bills while he composed. And if he thought of it only as a means to an end, he never suggested that he did not enjoy playing chess.

Chess players almost always staked money on their games in the eighteenth century. This was gambling, to be sure, but because chess engaged the intellect and reduced the role of chance to insignificance, it was a much more respectable form of gambling than most others. These two circumstances, money at risk and the absence of chance, made it a necessity for a stronger player to offer odds to a weaker player. In general, a player gave odds to his adversary by giving pieces, that is, by beginning the game with one or more of his own pieces removed from the board; by giving opening moves, that is, by allowing his adversary the first move and perhaps a free move preceding the first move; or by giving a combination of pieces and opening moves. The same scale of values of the pieces that is used today for the purpose of analysis had already been established in the eighteenth century for the purpose of giving odds. The scale runs, from the least valuable to the most valuable piece: pawn, knight, bishop, rook, queen, and king, the last of whose value, by the rules of the game, is absolute. The opening move was and is considered to be worth some fraction of a pawn. One pawn and the first move constituted the minimum that Légal, his reputation established, or Philidor, having caught up with his master, ever gave to other players.[19]

This system may have developed in response to necessities within the eighteenth-century chess microcosm, but it also reflected the social macro-cosm of eighteenth-century France. French society, or at least its upper 10 percent of aristocrats, clergymen, large landowners, merchants, civil servants, and professionals, was acutely status-conscious. If a stronger player offered odds to a weaker player partly to draw him into a game, he also did it partly to maintain his own superior status. For the stronger player, it was considered more honorable to lose while giving odds than to win while playing without odds, which constituted an admission that the presumed inferior actually had the rank of an equal. Of course if the presumed superior player lost consistently while giving odds to the presumed inferior, eventually he had to give up his pretense, or at least his fortune. Or he could refuse to play his presumed inferior any longer when he saw a disturbing trend developing, and this does not appear to have been a particularly unusual course of action, or inaction, to take. Which may explain a 1787 reference to Légal and Philidor: “The last match these gentlemen played was in 1755 when the Scholar beat his Master.” [20] That is, the two best players in France, habitués of the same café, had not played each other for more than thirty years.

When Philidor, soon after returning to Paris from his nine years abroad, defeated his former teacher Légal in that last match of theirs, he became in all likelihood the best chess player in Europe. But during the next fifteen years he conducted a productive and successful career in music and we hear little about “his diversion.” Philidor stayed in Paris, wrote a long string of comic operas, and acquired a reputation as one of France’s leading composers. His success began with Le Diable à quatre (1756) and Les Pèlerins de la Mecque (1758), and peaked with Le Sorcier (1764), Tom Jones (1765, based on the novel by Henry Fielding), and Ernelinde (1767). Companies throughout Europe staged these operas.[21] He also married a musician. Angélique-Henriette-Elisabeth Richer sang, occasionally as a concert soloist, and played keyboard instruments. Her three brothers were all musicians, and one of them, Louis-Augustin Richer, had attained contemporary celebrity as a singer and singing master. Often Philidor’s wife, and sometimes one or more of his brothers-in-law, rehearsed his compositions for him so he could hear how they sounded, since he himself neither played nor sang.[22]

The beginning of this period in Philidor’s life coincided with one of the many civil wars of French cultural history. Its theater happened to be the opera, and since the invading forces championed an Italian form known as opera buffa, it was called the querelle des bouffons. Paris society cleaved into two camps, favoring either the French traditionalists or the Italianizing innovators. Led by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the philosophes generally sided with the latter.

Rousseau and Philidor were friends, at least for a short while. Philidor helped the philosophe with the music for his first opera, Les Muses galantes (1745). Rousseau reported that Jean-Philippe Rameau, the reigning monarch of French music and the uncle of “Rameau’s nephew,” said of the opera that “a part of what he had just heard was the product of a consummate artist, and the rest that of an ignoramus who knew nothing of music.” Rameau himself corroborated this report of his judgment. A biographer of Philidor, not surprisingly, concludes that Philidor’s contribution was the part singled out for praise by Rameau. Rousseau, in contrast, wrote that Philidor came twice to work on the opera, “but he could not commit himself to laboring diligently for a distant and uncertain profit. He did not return again and I finished the task myself.” Since the score of the opera has long since disappeared, the last word may have been had by the music historian who declined to judge between them, musing, “it would be interesting to know whose genius intermittently flashed.” [23]

In the querelle des bouffons, Rousseau won the biggest victories both on and off the stage. His second opera, Le Devin du village, composed with no help from Philidor, attracted legions of listeners and piled up four hundred performances between its début in 1752 and 1829. His pamphlet salvo of 1753, Lettre sur la musique française, provoked a huge outcry by targeting the “fictitious ‘style’” of the French: “To make up for the lack of song, they have multiplied accompaniments…[and] to disguise the insipidity of their work, they have increased the confusion. They believe they are making music; but they are only making noise.” [24] Contemporaries generally counted Philidor among the Italianizers, although in music he was not a theorist.[25]

From a later perspective, Philidor’s music seems ambiguous with regard to the querelle des bouffons, especially if one accepts Rousseau’s drawing of the battle lines. Rousseau associated the Italianizers with melody, “pure song,” and freedom from both affectation and ornamentation, and the French traditionalists with harmony, “style,” and artful accompaniment. F.-J. Fétis, a highly influential nineteenth-century conductor, composer, teacher, critic, and historian of music, judged that “Philidor showed himself to be a much more skillful harmonist than the [other] French composers of his time, and despite what has been said, he did not lack melody.” [26]

Rousseau had previously tried his hand at chess and, as in music, sought Philidor’s assistance early. In a passage whose echoes we will hear repeatedly, Rousseau confesses:

Diderot’s character “Rameau’s nephew” expresses a similar attitude toward chess and other activities:I made the acquaintance of M. de Légal, of a M. Husson, of Philidor, of every great chess player of the time, and did not become, for all that, any more skillful. Nevertheless, I had no doubt that in the end I would become stronger than all of them, and that was enough for me to keep me playing. I always reasoned in the same way about every foolish thing that infatuated me. I said to myself: Whoever is the best at something is sure of being well known and sought out. Let me be the best then, at no matter what; I will be sought out, opportunities will present themselves to me, and my natural abilities will make me a success.[27]

Shortly after this exchange, “Rameau’s nephew” calls himself mediocre and says that he envies genius. It turns out that he once thought of himself as a genius but eventually ceased believing it.Ah ha! There you are, monsieur philosophe. And what are you doing here among this crowd of good-for-nothings? Do you also waste your time pushing wood? (That’s how one scornfully refers to playing chess or checkers.)

myself:No, but when I have nothing better to do, I entertain myself by watching those who push well.

he:In that case you are rarely entertained; leaving aside Légal and Philidor, the others don’t know what they’re doing.

myself:And M. de Bissy?

he:He is to chess what Mlle Clairon is to acting: As players, they both know everything that one can learn.

myself:You are difficult to please; I see you spare from criticism only sublime genius.

he:Yes, in chess, checkers, poetry, eloquence, music, and other nonsense of the sort. What good is mediocrity in those endeavors?[28]

The relentless drive to become the best that Diderot ascribes to a younger “Rameau’s nephew” and that Rousseau ascribes to his own younger self stands in sharp contrast to the wit and irony that most of the philosophes brought to their activities. Another striking and related similarity between the two youths, and again contrasting with the philosophes, is their idea that chess is equivalent to other arts, in the sense that it is worthwhile to devote one’s life to it and that a great chess player is comparable to a great artist. It has been argued that Diderot’s character “Rameau’s nephew” is in large part a caricature of Rousseau. Diderot and Rousseau were in fact introduced to each other in the Café de la Régence; perhaps they became acquainted across a chessboard, and perhaps Diderot chose this scene of their meeting as the setting for a satire of the opinions of his former friend and current enemy. Other commentators have interpreted the character “Rameau’s nephew” as one side of Diderot’s own personality.[29] In any case, if a few advanced thinkers such as Rousseau and “Rameau’s nephew” could consider making almost any activity at which one excelled a full-time occupation, Philidor still considered chess, though worth study, “only his diversion.”

| • | • | • |

In the last quarter of the eighteenth century, the Age of Revolution began and Philidor’s music became passé, so he set up chess in its place. Europe’s first chess club may have been the one founded by a group of English players in 1770 in London. A second club appeared there four years later, whether in competition with or as a replacement of the first is not clear. In any case, it immediately acquired an aura of fashionability, attracting as members enlightened intellectuals, politicians, and aristocrats such as Edward Gibbon, Charles James Fox, and the marquess of Rockingham. In the early 1770s Philidor traveled to England twice. He undertook the first trip, at least in part, for the purpose of trying to secure the publication of an expanded edition of his chess treatise, which Diderot had helped him plan; the second for unknown reasons. A convergence of interests manifested itself in 1775 when the new chess club induced Philidor to cross the Channel and stay for the duration of the London season, February to June. He subsequently made a similar sojourn every year until his death in 1795. In exchange for his coming to London to provide them with first-rate competition, the English players arranged for him to earn, in addition to his honorarium, a comfortable living teaching, giving exhibitions, and publishing new editions of his book. He may also have taught music independently. All this enabled him to take money home to Paris for the support of his family.[30]

Thus, for the last twenty years of his life, Philidor spent from mid-February to mid-June in London playing chess and—until the Reign of Terror—from mid-June to mid-February in Paris giving music lessons and composing. He had less and less success with his compositions. No new works of his seem to have been performed in public in the four years from 1775 through 1778. In the latter year he composed music for Horace’s choral hymn Carmen seculare, the original music for which had been lost in antiquity. He managed to have it staged three times in London in 1779, three times in Paris a year later, and several more times in Paris in subsequent years; it received high praise from critics in both cities.[31] Through careful preparation, Philidor made the Paris premiere into a society event. He secured a hall in the Tuileries Palace; he chose a Wednesday, when no classes were held at the University of Paris; he sold tickets in advance; and he had a program printed up giving the text in both Latin and French. A contemporary chronicler reported before the concert:

The same chronicler reported after the concert that it had been attended by “a numerous and distinguished assembly,” who had listened to it “with sustained interest and often with outbursts of enthusiasm.” [32] Then passed another stretch of four years, 1781 through 1784, when again no new works of Philidor were performed. In the last decade of his life, he scored two more successes with a Te Deum (1786) and a comic opera, La Belle esclave (1787), but also several failures.[33] There is no evidence of his playing chess in Paris during this period, although the French players founded a club of their own in 1783. It met in some rooms of the Palais-Royal, a palace being renovated by the enlightened duc de Chartres—called “Philippe Égalité” during the Revolution—quite near the Café de la Régence.[34]M. Philidor is doing his best to excite the public, through his own efforts and those of his friends, to purchase tickets for the performance that he is putting on today; he has had one of his partisans write a letter, printed in the Journal de Paris, no. 17, in which the report of the prodigious success his Carmen sæculare had in the capital of England is reiterated; and he has gathered together the support of the three factions into which music lovers are divided.

Philidor expanded his Analyse du jeu des échecs twice, doubling the original size of the book in 1777 and then redoubling it to two volumes in 1790, both times bringing out the new edition in London. The list of subscribers to the 1777 edition resembled the membership list of the London chess club in its social mix, although it contained French names as well as English. Among intellectuals, Diderot, Voltaire, Marmontel, and Gibbon subscribed for copies. The first expansion consisted mostly of endgame analyses. With these he took another long stride ahead of his predecessors. He specified whether the side with the material advantage would win or could only draw, if both sides played the best possible moves, for certain generalized advantages. For example, he said that a side having a rook and bishop left with its king, facing a side with only a rook and king, should win, whatever the placement of the pieces on the board, with the exception of a few extreme cases. He did this for many more kinds of advantage than his predecessors had done; he was usually correct; and for some of them, for example the rook and bishop against rook ending, he gave the definitive analysis. That is, he explained correctly how one can always checkmate with a rook and a bishop against a rook.[35] Incidentally, the piece that the anglophone world calls a bishop is known in France as a fou (jester)—scant difference, from the point of view of the anticlerical philosophes. The 1790 edition contained both more opening and more endgame analyses, as well as the records of some of Philidor’s recent blindfold matches.

Philidor’s music distinguished itself above all by its technical perfection. Musicologists return to this point again and again. Composition classes at the Conservatoire de Musique used his works as models for many years. The fact that Rossini praised Philidor’s music to the latter’s granddaughter perhaps shows nothing but social grace, but the nature of the praise is significant: “All composers make mistakes, and I count myself first; Madame, none have ever been found in the works of your illustrious grandfather; he never made any.” [36] André Grétry, Philidor’s successor as the leading comic-opera composer in France, struck more of a balance in his eulogy of his predecessor:

To invent something entirely new in the arts is impossible; but to add some new beauties to those already known is sufficient to succeed and to merit the title of genius. Philidor is, I believe, the inventor of that kind of piece which uses several contrasting rhythms; I had never heard such things in the theaters of Italy before coming to France. How easily the vigorous intellect of this justly famous and sorely missed artist could grasp difficult combinations is well known. He would arrange a succession of sounds with the same facility that he followed a game of chess. None could vanquish him at this game of combinations; no musician will ever put more power and clarity into his compositions than Philidor put into his.[37]

Did some common skill in fact connect Philidor’s achievement in chess with his achievement in music? Unfortunately, he himself left us no thoughts on so interesting a subject. A few other chess masters have also excelled at music: The mid-nineteenth-century Café de la Régence master Lionel Kieseritzky, a man of many talents, was an excellent amateur pianist, as was the Hungarian master Vincenz Grimm of the same era; Mark Taimanov, one of the top grand masters in the world in the early 1950s, was a concert pianist, and Vassily Smyslov, world champion in 1957–58, an opera singer.[38] Some sort of correlation seems to exist, although certainly not every great chess player has also been a great musician. Likewise probable appears an association between a particular kind of skill in chess and a particular kind of skill in music, but this, too, remains nebulous.

Philidor gave simultaneous blindfold exhibitions during his annual sojourns in London probably beginning in 1782. As far as we know, he had not given such an exhibition since 1751 in Potsdam, and never before in front of a paying audience. These performances, sponsored by the chess club, undoubtedly had the purpose of contributing to Philidor’s earnings and of adding another incentive to induce him to continue making his regular visits. The club advertised the events in the London newspapers, inviting the public to attend. Thirty-three people came to one of them, in 1787, and forty-three to another, in 1790, not counting club members. Several of the exhibitions attracted reporters.

After his début in 1782, Philidor gave at least two performances in 1783, at least one in 1787, at least two in 1788, at least four in 1789, and at least fifteen in the 1790s. In some of these matches, he played three simultaneous blindfold games; in others, three simultaneous games, two blindfolded and one with sight of the board; in a few of them, only two simultaneous blindfold games. To infer from the frequency and dates of the known exhibitions, they probably began as exceptional events and gradually increased in regularity up to a rate of once every two weeks during his annual four-to-five-month stay in London.[39]Yesterday, at the Chess-club in St. James’s-street, Mr. Philidor performed one of those wonderful exhibitions for which he is so much celebrated. He played at the same time three different games, without seeing either of the tables. His opponents were, Count Bruhl, Mr. Bowdler (the two best players in London), and Mr. Maseres. He defeated Count Bruhl in an hour and twenty minutes, and Mr. Maseres in two hours. Mr. Bowdler reduced his game to a drawn battle in an hour and three quarters. To those who understand Chess, this exertion of Mr. Philidor’s abilities, must appear one of the greatest of which the human memory is susceptible.

Philidor approached these exhibitions almost as if they were athletic contests, putting himself through a sort of regimen in preparation for them. He invariably played at the same time of day and took care to eat only lightly before the event, reserving dinner until afterward. In fact, he regulated his diet for several days previously and refused to play on short notice.[40]

Considering his annual visits to the London chess club, the revisions of his chess treatise, and his blindfold exhibitions, Philidor was putting a lot more energy into chess than he had at any period of his life since the three youthful years he spent studying with Légal. He also increased his personal investment in it. He gave no odds in England, from the 1770s onward, of less than a knight. This was for ordinary games; the odds were reduced for blindfold play. A later Café de la Régence master observed: “He showed just as much superiority at checkers, but he did not stake as much of his pride on it as he did on chess.” [41]

Philidor, the composer of comic operas, had always struck his contemporaries as a bit too serious. He was so accustomed to deliberate thinking that for the most part jokes were lost on him. Instead, he became their target. One of his relatives liked to amuse himself at Philidor’s expense: “‘Mon Dieu, how I would like to have a carriage! I would seat myself at my window and enjoy watching myself drive by.’ ‘That’s stupid, my friend,’ Philidor said to him quite seriously, ‘you couldn’t be in your carriage and at your window at the same time; thus you couldn’t see yourself pass by.’” His principal occupations had a tendency to absorb him completely. He twisted his body continually whenever he was deep in composition or chess play, a habit his wife referred to as “playing the silk-worm.” [42]

His contemporaries did not find him an engaging conversationalist. An article on Philidor in a biographical dictionary of musicians that was published a few years after his death reported: “He had a reputation for lack of wit; thus Laborde, one of his greatest admirers, hearing him make a large number of trite remarks at a dinner party, extracted him from his embarrassment by interjecting: ‘See this man, he has no common sense; he’s all genius.’” [43]

Philidor was no boor, but neither did he take the trouble to cultivate the social graces beyond the point of simple politeness. This made him an exception among eighteenth-century French intellectuals. Most of his energy went into his composing and his chess playing. We hear very little about him amusing himself. He was happily married and seems to have been a conscientious and loving father to his children. He gave assistance generously to struggling young musicians.[44] But he also thought highly of his own powers and pushed himself to develop them.

Philidor’s seriousness and his commitment to chess intensified in tandem in his later years. He wrote to his wife in 1788: “There are astonishing panegyrics in all the newspapers, on the subject of the three blindfold games I played last Saturday; they say that the clarity of my thinking increases with my years; it is true that never have I had such a clear head.” The following year he wrote: “I have a great desire to prove that old age has not yet extinguished my genius.” And after another year, when he was giving blindfold exhibitions every two weeks: “I assure you that this does not tire me as much as many people would believe,” although a month later he admitted, “I am exceeding my strength at present.” [45] Undoubtedly his faltering career in music, its sharp contrast with his spectacular success in chess, and his need to earn money one way or another all contributed to the reorientation of his attention and pride toward the latter activity.

In its report of a simultaneous blindfold exhibition given in 1837 by a later Café de la Régence master, Labourdonnais, the newspaper La Presse naturally referred to Philidor’s exhibitions and mentioned that the spectators had paid a guinea per person to attend them. Philidor’s son replied in a letter to the editor that his father’s purpose had not been to make money. The controversy flared up again in a chess journal a decade later when it fell to Philidor’s grandson to defend his honor: “These matches, far from being the pretext for a benefice maintained by taxing the spectators at the rate of a guinea per person, were only engaged in by Philidor out of condescension for the members of the Chess Club, who pestered him relentlessly that they might enjoy such an astonishing spectacle.” [46] Reluctant as his descendants were to admit it, Philidor had become a professional chess player.

He himself had shown the same reluctance: “It is ridiculous that the composer of Ernelinde should be obliged to play chess for half of the year in England in order to keep his numerous family alive.” [47] Philidor had his moments of unhappiness and, while contemplating the decline of his once-glorious musical career, even bitterness. But everything indicates that he both enjoyed chess and relished his success at it. Regrets or no regrets, he dedicated himself to making a second career out of it. His arrangement with the London chess club anticipated in a striking way that of a twentieth-century tennis pro with a racquet club or a golf pro with a country club.