The Mainspring of the Future: Playing the Field

While all artists are not chess players, all chess players are artists.

—Marcel Duchamp

When asked by Katherine Kuh, one of his interviewers, which of his works he considers to be the most important, Marcel Duchamp replied:

As far as date is concerned I'd say the Three Stoppages [3 stoppages étalon ] of 1913. That was really when I tapped the mainspring of my future. In itself it was not an important work of art, but for me it opened the way—the way to escape from those traditional methods of expression long associated with art. I didn't realize at that time exactly what I had stumbled on. When you tap something you don't always recognize the sound. That's apt to come later. For me the Three Stoppages was a first gesture liberating me from the past.[34]

As Duchamp subsequently explains, the idea of letting a piece of thread fall on a canvas was accidental, but "from this accident came a carefully planned work."[35] What exactly did Duchamp stumble on that enabled him to escape the traditional means of expression associated with art? Was it the idea of chance, or its plastic deployment and embodiment as an event or work? Before exploring in more detail the role of Three Standard Stoppages (3 stoppages étalon; 1913–14) as a gesture that would liberate him from the past, one must first understand how this work emerges out of Duchamp's pictorial experiments, for this work decisively signifies both his break with painting and his strategic turn toward the ready-mades and The Large Glass.

Duchamp's interest in chance as a way of redefining conventional forms of artistic expression appears early on in his paintings and is tied to his interest in chess. For Duchamp, chess is not merely a pastime or an ordinary game because its intellectual character represents for him a plastic

Fig. 10.

Marcel Duchamp, The Chess Game (Le Jeu D'échecs), 1910. Oil on canvas,

44 7/8 x 57 1/2 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and Walter

Arensberg Collection.

Fig 11

Paul Cézanne, Card Players, 1892.

Courtesy of The Courtauld Institute Gallery, London.

and thus, by extension, an artistic dimension. As a strategic game that requires the interplay of two opponents, chess provides Duchamp with a new way of envisioning art in its dialogue with the tradition. The analogy of art and chess enables Duchamp to appropriate chance and redefine its plastic impact in a field of already given determinations. Starting with The Chess Game (Le jeu d' hecs; 1910) (fig. 10), and continuing through 1911, Duchamp produces a series of works dealing with chess. These include six drawings/sketches, which culminate in the painting Portrait of Chess Players (Portrait de Joueurs d'échecs; 1911).[36] These works range from a relatively conventional depiction of a chess game, to progressively more abstract renditions of the players, the board, and the chess pieces.

Duchamp's lifetime interest and preoccupation with chess is well known, but its significance and precise impact on his art is less recognized.[37] While Duchamp openly acknowledges his indebtedness of The Chess Game to Paul Cézanne's Card Players (1892) (fig. II), it is clear that he is already playing another game (DMD, 27). In The Chess Game the centrality of the table in Cézanne's Card Players is displaced on a diagonal axis along which there are two tables, one with a chessboard on it and another set in the manner of a still life.[38] Duchamp's choice to replace the card game with a chess game makes visible something that would otherwise remain invisible: the chessboard as a metaphor for the mental ground rules that define it as a game. The checkered pattern of the board, however, is also an allusion to another set of rules, those of Albertian perspective that have guided the development of painting.[39] This allusion is reinforced by the fact that the chess players are Duchamp's brothers, who are both practicing artists. If we pursue Duchamp's analogies in The Chess Game, art no less than chess emerges as a strategic, rather than purely plastic, domain. Both chess and perspective are systems whose normative standards prescribe and determine the nature of representation. What had been originally conceived as an arbitrary relation between painting and the world is now revealed to be a strategic, albeit conventional game, a chess game.

Why, you may ask, did Duchamp choose not merely to reshuffle Cézanne's cards but to play a different game altogether? The answer lies in his understanding of chess as a plastic, rather than a purely intellectual, game. As Duchamp's comments to James Johnson Sweeney indicate, playing

chess is like painting insofar as "it is like designing something or constructing a mechanism of some kind" (WMD, 136). This plasticity, however, is not in the realm of the visible but in the abstraction of the movement of pieces on the board. In his interview with Francis Roberts, Duchamp explains how the strategic and positional nature of chess generates plastic effects:

In my life chess and art stand at opposite poles, but do not be deceived. Chess is not merely a mechanical function. It is plastic, so to speak. Each time I make a movement of the pawns on the board, I create a new form, a new pattern, and in this way I am satisfied by the always changing contour. Not to say that there is no logic in chess. Chess forces you to be logical. The logic is there, but you just don't see it.[40]

The plasticity that Duchamp ascribes to chess is not aesthetic in the visual sense but rather intellectual. The movement of the pieces on the board creates patterns and forms whose contours are constantly shifting. This moving geometry is described by Duchamp as "a drawing" or as a "mechanical reality" (DMD, 18). As Duchamp elaborates: "In chess there are some extremely beautiful things in the domain of movement, but not in the visual domain. It's the imagining of the movement or the gesture that makes the beauty, in this case. It's completely in one's gray matter" (DMD, 18). The beauty that Duchamp appeals to is not one based on aesthetic categories, on visual appearance and artistic self-expression. Rather, the beauty in question is defined by the plasticity of the imagination, by the poetry of its ever changing contours.

The analogy of chess and art is one that is mediated by an allusion to the abstract nature of both music and poetry. As Duchamp explains:

Objectively, a game of chess looks very much like a pen-and-ink drawing, with the difference, however, that the chess player paints with black-and-white forms already prepared instead of having to invent forms as does the artist. The design thus formed on the chessboard has apparently no visual aesthetic value, and it is more like a score for music, which can be played again and again. Beauty in chess is closer to beauty in poetry; the chess pieces are the block

alphabet which shapes thoughts; and these thoughts, although making a visual design on the chessboard, express their beauty abstractly, like a poem. Actually, I believe that every chess player experiences a mixture of two aesthetic pleasures, first the abstract image akin to the poetic idea of writing, second the sensuous pleasure of the ideographic execution of that image of the chessboards.[41]

Relying on analogies to the media of music and poetry, Duchamp uses chess as a way of expanding the meaning of art. No longer bound to the creation or invention of visual forms, the chess player "paints" with already given black-and-white forms. The interest of the exercise lies in the composition of the design, a visual score that is open to multiple performances, for the nature and value of chess exists only as a performance, a duet where two interpreters put their heads together, so to speak. The chess pieces in this game function as linguistic elements already given by convention, but ready to be redeployed poetically in new ways. While subject to particular rules governing the possibility of movement, the mechanisms generated, as the "ideographic execution of that image," are always open to further reinterpretation. Thus Duchamp uncovers within chess a paradigm for the reinterpretation of aesthetic pleasure as a pleasure derived neither from invention nor the sensuality of the pieces themselves, but from their recomposition and poetic deployment as a game.

Is it then surprising that the later versions of The Chess Game, including the pen-and-ink drawings/sketches that culminate in the highly abstracted painting Portrait of Chess Players (fig. 12), represent a visual decomposition of the image in terms of the chessboard? Another painting from this period, Yvonne and Magdeleine (Torn) in Tatters (Yvonne et Magdeleine déchiquetées; 1911) (fig. 13), representing Duchamp's sisters, provides one with some verbal clues in regards to the mechanics of these images. The expression "torn in tatters" (déchiqueter, in French) means to hack, slash, tear to shreds, or tear up. As Duchamp explains to Cabanne, "this tearing was fundamentally an interpretation of Cubist dislocation" (DMD, 29). The word for tearing (déchiqueter, however, is also a pun on chessboard or checker pattern (ßchiquier, in French). Rather than interpreting this tearing as Cubist dislocation, Duchampis reinterpreting Cubism itself conceptually from the perspective of chess, as a game whose

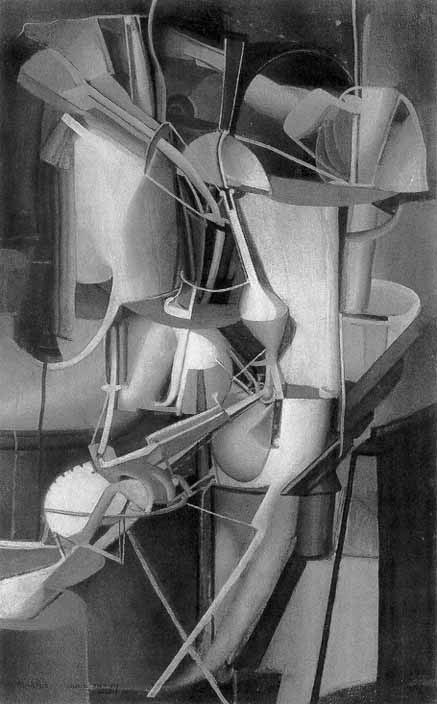

Fig. 12.

Marcel Duchamp, Portrait of Chess Players

(Portrait de Joueurs D'échecs), 1911. Oil on

canvas, 42 1/2 x 39 3/4 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art,

Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.

Fig. 13.

Marcel Duchamp, Yvonne and Magdeleine (Torn)

Tatters (Yvonne et Magdeleine Déchiquetées), 1911.

Oil on canvas, 23 5/8 x 28 3/4 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art,

Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.

illogical visual character becomes legible once seen from the perspective of chess. More specifically, the serial fragmentation and multiplication of the protagonists into shards, while depersonalizing them into mechanical patterns, illuminates painting in a new light. Duchamp visibly draws on Cubism, only to redefine its logic as a representation: the dislocations visible in the image are but the diagrams of movements ideographically transposed from chess.

While such an interpretation seems to force Duchamp's hand, as it were, it is important to recall Duchamp's comment to Cabanne regarding the fact that Portrait of Chess Players was painted not in ordinary light, but by gaslight:

This "Chess Players," or rather "Portrait of Chess Players," is more finished, and was painted by gaslight. It was a tempting experiment. You know, that gaslight from the old Aver jet is green; I wanted to see what the changing of colors would do. When you paint in green light and then, the next day, you look at it in day light, it's a lot more mauve, gray, more like what the Cubists were painting at the time. It was an easy way of getting a lowering of tones, a grisaille. (DMD, 27).

Duchamp's innovative use of a green gaslight as a way of lowering the color tones of this painting (grisaille, in French and in English) also func-

tions as a way of illuminating it from a conceptual or mental perspective (a pun on matière grise, in French). Rather than merely seeking to reproduce Cubist colors, Duchamp uses the "gas" light as a pun that reframes the notion of pictorial "gaze." The title Portrait of Chess Players alerts the viewer to the mise-en-abyme representational nature of this work: its visual character is mediated conceptually: "it's light that illuminated me" (DMD, 27). Duchamp's portrait (pourtraire, in French, from Latin, pro [forth] and trahere [to draw]) draws upon and restages earlier versions of chess games and chess players by redefining the meaning of pictorial representation as a practice that is not merely visual but also mental.

If the sequence of paintings and sketches from The Chess Game to Portrait of Chess Players represents Duchamp's artist brothers playing chess, in later paintings the chess pieces themselves become the subject matter of art. They take over the board, as it were. Having uncovered the affiliation between art and chess by revealing their shared strategic and positional nature, Duchamp now proceeds to examine the plastic dimension of the mechanics of strategy. As Duchamp observes: "In chess, as in art, we find a form of mechanics, since chess could be described as the movement of pieces eating one another."[42] This analogy highlights another aspect of chess—its adversarial nature—which is equally applicable to art, for Duchamp's own effort to rethink painting means devising new strategies for an old game. Whether his adversaries may be his own brothers, who were also artists, or artistic movements such as Cubism, Duchamp's understanding of art as a strategic game enables him to redefine the notion of artistic creativity as a form of production based on reproduction. Duchamp's redefinition of art in terms of chess involves, on the one hand, accepting one's affiliation to traditions, that is, the readymade character of pictorial convention, and on the other hand, the effort to redraw the board in order to radically rethink the terms of the game. Consequently, artistic innovation is freed from the "anxiety of influence," since tradition itself provides conventional or ready-made elements that Duchamp can redeploy in a strategic fashion.[43]

Following Portrait of Chess Players and Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, Duchamp produces a set of sketches and paintings whose mechanomorphic appearance is underlined by titles that pursue chess analogies. Among the most significant are The King and Queen

Surrounded by Swift Nudes (Le Roi et la Reine entourés de nus vites; May 1912) (fig. 14) and The PASSAGE from the Virgin to the Bride (Le Passage de la Vierge à la Mariée; 19) (fig. 15), the latter being one of the preliminary works to The Large Glass. According to Duchamp, the title "'King and Queen' was once again taken from chess, but the players of 1911 (my two brothers) have been eliminated and replaced by the chess figures of the King and Queen."[44] In the case of The PASSAGE from the Virgin to the Bride, the chess analogy is embedded in the notion of marriage implicit in the transformation of the virgin into the bride. In some card games, pinochle for instance, the term marriage refers to the combination of the king and queen of the same suit. In these paintings we are witnessing the passage from chess analogies into works whose diagrammatic character begins to challenge the very limits of art.

The King and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes was painted on the back of an earlier painting, Paradise, which was turned upside down. Commenting on this work to Katherine Kuh, Duchamp notes:

You know this was a chess king and queen—and the picture became a combination of many ironic implications connected with the words "king and queen." Here the "swift nudes," instead of descending, were included to suggest a different kind of speed, of movement—a kind of flowing around and between the two central figures. The use of nudes completely removed any chance of suggesting an actual scene or an actual king and queen.[45]

The irony in question here involves the substitution of chess pieces for the traditional subject matter of painting, which as reproductions put into question the referential status of painting. His choice of renaming the nudes in terms of their quality or agility of movement was "literary play," a way of transposing sport terminology into painting.[46] The juxtaposition of the king and queen with the "swift nudes," which are reproductions of Duchamp's earlier descending nudes, redefines painting itself as a space of reproduction, where visual appearance is merely the diagrammatic record of various transitions.

When discussing the relation of Nude Descending a Staircase and The King and Queen Traversed by Swift Nudes (Le Roi et la Reine traversés

par des nus vites; April 1912), Duchamp describes it as minimal, except that they share "the same form of thought": "as for the swift nudes, they were the trails which crisscross the painting, which have no anatomical detail, no more than before" (DMD, 35). The introduction of speed into these paintings is not merely a concession to Futurism but rather the affirmation of the affinity between art and chess. If playing chess is like designing or constructing a mechanism, then art becomes a way of setting this mechanism into motion strategically. Instead of visually representing motion, Duchamp, following Marey's chronophotographic techniques, maps it as a "system of dots delineating different movements" (DMD , 34). He thus reduces the intervention of vision by demonstrating that all the visible traces are but forms of ideographic mapping. By interpreting painting as a conceptual intervention that converts visible objects into cartographic networks, Duchamp redefines painting as a philosophical enterprise. As Octavio Paz observes:

Fig. 14.

Marcel Duchamp. The King and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes (Le Roi et la Reine

Entoures de Nus Vites), 1912. Oil on canvas, 45 1/8 x 50 1/2 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.

Fig. 15.

Marcel Duchamp, The Passage from the Virgin to the Bride

(Le Passage de la Vierge à la Mariée), 1912 Oil on canvas,

23 3/8 x 21 1/4 in.

Courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

In these canvases the human form has disappeared completely. Its place is not taken by abstract forms but by transmutations of the human being into delirious pieces of mechanism. The object is reduced to its most simple elements: volume becomes line; the line a series of dots. Painting is converted into a symbolic cartography; the object into idea. It is not the philosophy of painting but painting as philosophy.[47]

The painting The passage from the Virgin to the Bride (fig. 15) thus literalizes a transition that Duchamp is effecting from visual to conceptual painting. The resonant tension that this work sustains between abstraction and figuration is amplified by the punning echoes of the title. Itself a transitional work, between two preliminary sketches Virgin No. 1 and Virgin No. 2 , this painting is a study for the final painting of Bride (Mariee; 1912) (fig. 16). The "passage" in question here refers both to the intermediary status of this work and, more importantly, to the redefinition of painting itself as a transitional activity, a "rite of passage" of sorts.

Fig. 16.

Marcel Duchamp, Bride (Mariee), 1912. Oil on canvas, 35 1/4 x 21 5/8 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.

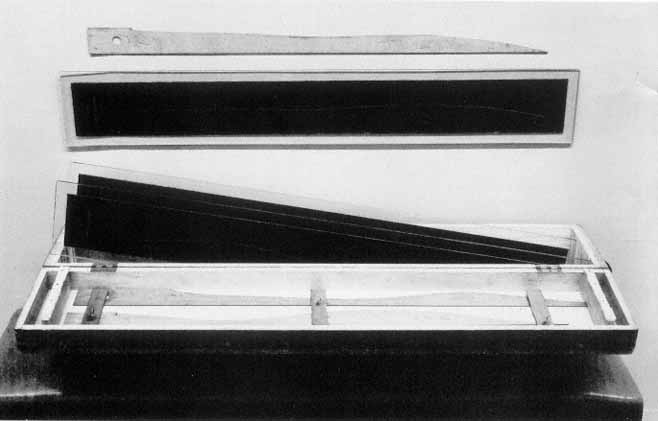

Fig. 17

Marcel Duchamp, Three Standard Stoppages (3 Stoppages Étalon), 1913–14. Semi-Ready-Made Three Threads, one meter in

length, dropped from a height of one meter and glued to preserve their outline onto a canvas painted Prussian blue. The canvas

was cut into three strips (47 1/4 x 5 1/4 in .), which were then glued onto three glass panels (49 3/8 x 7 1/4 in.) ) Three flat wooden

strips (47 x 2 3/8 in; 42 7/8 x 2 1/2 in ., and 43 1/2 x 2 1/2 in) were cut to repeat the curves of the threads. The entire assembly is

enclosed in a wooden box (50 7/8 x II x 9 1/8 in .)

Courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Katherine S. Dreier Bequest

If engraving has enabled Duchamp to conceive painting itself as a transitional activity, as a set of impressions or imprints, chess enables him to redefine it strategically. From the chess Queen of King and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes, Duchamp now stages the process of becoming painting, the passage from visual ("Virgin") to conceptual ("Bride") painting. As Thierry de Duve observes: "the painting does what it says, and says what it does," but in so doing it opens up the space for a new kind of passage, away from painting altogether.[48] By visibly deploying the strategies that define painting, Duchamp effectuates a climactic passage through painting that opens up the possibility of resituating artistic activity within a terrain that no longer requires the confines of the pictorial space or the handiwork of the brush. The nuptial rites that The PASSAGE from the Virgin to the Bride initiates and enacts by covenant involve the redefinition of both painting "the Bride" and the painter, as "the groom." Duchamp, however, is no ordinary groom in the sense of assuming the position of a liveried servant, that is, an inferior attendant in relation to painting. His job is not that of an ordinary groom—merely to equip, prepare, or dress up painting—but rather, equipped with the insights that painting provides, he draws on painting in order to redefine the meaning of art.

Given Duchamp's exploration of the limits of painting as a kind of end game (to use an expression that is common in chess), it is not surprising that by 1913 he begins to envisage leaving it behind altogether. He starts experimenting with chance operations, which, while drawing on pictorial traditions, also announce his future discovery of the ready-mades. As Duchamp himself noted, Three Standard Stoppages (fig. 17) represents a radical turning point in his work, marking his abandonment not only of painting but also of the conventional notions of art. This work is an assemblage (a semi-ready-made) consisting of a croquet box that contains three separate measuring devices that were individually formed by chance operations. Three different threads, one meter in length, were dropped (or allowed to fall freely, depending on one's perspective) onto a canvas painted Prussian blue, and glued into place. The resulting impressions, capturing the curved outline of their chance configurations, were then permanently affixed to glass plate strips. These plates served as imprints for the preparation of three wood templates.

Designated as an instance of "canned chance," this work is also categorized by Duchamp as "a joke about the meter."[49] Francis M. Naumann concludes that "the central aim of this work was to throw into question the accepted authority of the meter," as a standard unit of measurement.[50] Duchamp's own description of this work, as "three meters of thread falling and changing the shape of the unit of length," verifies Naumann's contention with a twist. Not only does Three Standard Stoppages distort the length of the meter through curvature but in doing so, it demonstrates the recognition that the meter itself as a unit of length is generated through approximation: the straightening out, as it were, of a curved meridian.[51] Duchamp sets the viewer straight by graphically showing that the authority of the meter as a measuring device relies upon distortions that he corrects through chance operations.

While this work may parody the authority of the meter, and thus by extension challenge notions of authority in general, it is less clear whether it reflects Duchamp's effort to champion individual rights, as Naumann claims.[52] As a quasi-scientific device, Three Standard Stoppages draws on the authority of a scientific standard, only to uncover its arbitrary and institutionally sanctioned character. Duchamp's invocation of chance is not a strategy to personalize the laws of physics but merely to ironically "strain" its laws in order to reveal their instability. As he explains:"I was satisfied with the idea of not being responsible for the form taken by chance."[53] Chance suspends the notion of personal responsibility by redefining the notion of artistic creativity as a form of production whose plasticity is contingent rather than deliberate.

Duchamp's experiment with "canned chance" not only questions scientific authority but also notions of artistic authority, which by their embedded and ingrained character reduce art to a mechanical practice. Roberts's question whether the dependence on chance betrays a disdain for the mechanics of art, leads Duchamp to respond:

I don't think the public is prepared to accept it . . . my canned chance. This depending on coincidence is too difficult for them. They think everything has to be done on purpose by complete deliberation and so forth. In time they will come to accept chance as a possibility to produce things. In fact, the whole world is based on

chance, or at least chance is a definition of what happens in the world we live in and know more than any other causality.[54]

The notion of coincidence challenges through its arbitrary logic both personal and institutional forms of determinism. More important still, it puts into question the voluntaristic and intentional logic that defines the creative act and the identity of the artist. To assume chance as a locus for production is to understand causality itself not as an origin but as a productive event, whose plasticity can redefine the notion of artistic creativity.

While Three Standard Stoppages captures the "form taken by chance," it does so not as a unique event but as a series of impressions that are recorded first on canvas, then on glass, only to become the molds for a set of wood templates. The first set of chance operations is twice reproduced, each time redrawing the meter and reshaping it as the unit of length. The systematic transposition of the impression of the string to the painterly surface, which is affixed to glass, becomes like a printing plate that generates the outline of wood templates as its photographic negative. In this work we begin to witness the stripping bare of painting, the reduction of its operations to chance understood as a mode of production that relies on "mechanical" conventions. Under the rubric "The Idea of Fabrication," Duchamp discusses the compositional strategies of this work: "3 patterns obtained in more or less similar conditions: considered in their relation to one another, they are an approximatereconstitution of the measure of length" (WMD , 22). Chance deployed as a strategic set of operations replaces the notion of pictorial composition by that of fabrication, a mode of production defined by reproduction.

When Duchamp playfully suggests that Three Standard Stoppages may be a "joke about the meter," he also opens up the possibility that the meter in question may involve a poetic and musical referent, rather than a purely metric one.[55] In poetry the meter is not a unit of length but is instead an indicator of rhythm: a measured arrangement of a line of verse, or groups of syllables, having a time unit and regular beat. This may explain why Duchamp in the Box of 1914 refers to Three Standard Stoppages as "the meter diminished" (WMD, 22). Duchamp's efforts to "diminish" the meter are visible in his musical experiment Erratum Musical (from The Green Box; 1934) (fig. 18), which lacks both time signatures and measure markers.

Fig. 18

Marcel Duchamp, Erratum Musical, from The

Green Box, 1934 8 x 10 in

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art,

Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection

As Carol P. James explains: "To bend meter in music, Erratum actually straightened it out, giving each note the same time value. Having no difference of length in relation to each other, the notes have no real time at all; all are equally hollow."[56] Just as Duchamp straightened out our idea of the meter, so does Duchamp in Erratum bend the notion of musical meter, by straightening it out and thus reducing it to meaninglessness.

In his Erratum Musical Duchamp sets to music a randomly chosen dictionary definition of the verb "to print": "Make an imprint mark traits a figure on a surface print a seal on wax" ("Faire une em-prein-te mar-quer des traits u-ne fi-gure sur une sur-face im-pri-mer un sceau sur ci-re" ).[57] This definition of printing as a mode of impression also alludes to the fate of music in the modern age, the fact that early recordings of sound were made in wax. As James observes: "The text of the Erratum cannily repeats the processes of reproduction of meaning, be they the printing of alphabetic letters, the visual traces codified as representations of meaning, i.e., writing, or do-re-mi (mi sol fa do ré) of the musical code recorded in

wax."[58] This insistence on printing as a recording device captures its affinity with music as a medium that generates "meaning" through successive reproductions. Whether it is a question of a figure or a melodic line, representation in prints or in music challenges conventional modes of artistic creativity, since meaning is constructed reiteratively and successively, rather than in the sweep of an off-handed manner.

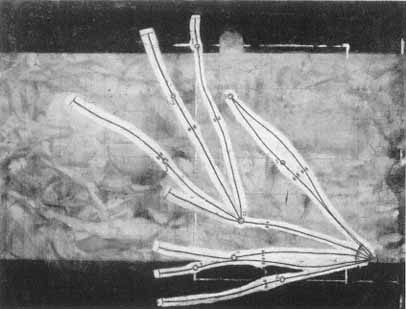

Following Three Standard Stoppages, Duchamp transposes his experiments with chance operations back onto one of his last pictorial works entitled Network of Stoppages (Réseaux des stoppages étalon; 1914) (fig. 19). This work marks Duchamp's effort to contextualize chance not merely as an event but as a set of reiterative impressions whose plasticity is diagrammatic—a cartographic network. It involves the mirrorical return onto painting of chance operations exercised in Three Standard Stoppages. Using an already painted vertical canvas, Duchamp rotates it horizontally, divides it into two sections, and lightly repaints over the right section in white wash. This gesture anticipates his sectioning into two regions that we later find in The Large Glass. Duchamp remaps on the surface of an

Fig. 19

Marcel Duchamp, Network of Stoppages (Réseaux des Stoppages Etalon),

1914. Oil and pencil on canvas, 58 5/8 x 77 5/8 in.

Courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

already given painting, a set of bifurcating lines and angles that redefine the painting as symbolic cartography. He redeploys chance operations by drawing upon painting, only to redraw painting itself according to the plastic logic of the network stoppages. Proceeding from chance understood as a stopgap measure, Duchamp generates a set of imprints whose reproductive character serves to redefine the originality of pictorial practice.