4—

Rocky Horror Playtime Vs. Shopping Mall Home

Seven weeks ago, when I received a call from Adriano Aprà in Rome inviting me to speak at this conference, I was in my hometown, Florence, Alabama, where my parents live today.[*] I have moved with all my belongings seventeen times in the past twenty years, and I will have to find and move to yet another place in New York as soon as I return from this conference. Nevertheless, I consider myself unusually fortunate, fortunate not only in being here—in this city and this country for the first time in my life—but in having a hometown to return to year after year: a fixed reference point. And fortunate in being the grandson of the man who ran most of the local movie theaters when I was growing up, which meant that I had virtually unlimited access to most of what was shown.

Moving Places is an attempt at a narrative exposition of myself through movies and of movies through me, and Florence has been providing me with a sort of personal and historical measuring stick in this process. So when Adriano told me that I was to speak about audiences in the 1980s, I naturally thought first about the audiences in Florence, what they were and what they are, which is my most reliable guide to what they will be.

I have to admit that Florence has undergone radical social changes since I left in 1959. The town is now racially integrated, which wasn't the case when I was growing up. Today black people in Florence don't have to attend sepa-

rate schools, use separate bathrooms (in the nearest train station one facility was labeled "colored women," the other "white ladies"), or drink from separate drinking fountains. State law no longer requires them to sit in the back of a bus or in a special section of a movie theater.

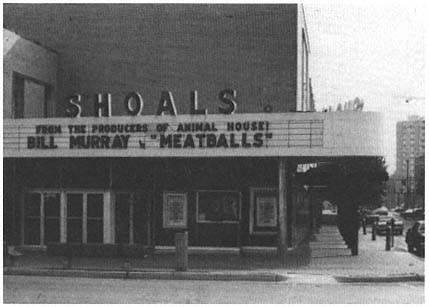

Another drastic change is that downtown Florence is dying, perhaps almost dead. The center of town, where three of my grandfather's theaters once stood—each of them only a block or so from where the courthouse used to be—now seems deserted. Despite lots of brand new parking lots, the place feels haunted, like a ghost town. The largest of the three theaters, the Shoals—built when I was five and originally seating 1300 people—is the only one standing today. It still shows movies; I saw Meatballs there three days after Adriano phoned. But it no longer functions as anything like the place of worship or the community gathering-place that it was twenty and thirty years ago.

The cashier's booth at the Shoals used to have two windows, one around the corner from the other, in order to conform to the Jim Crow laws. The window directly in front of the cashier was for selling tickets to white folks; the one on her left was for black customers, who had already come into the building through a special side entrance. At the side window they would purchase "colored" tickets, which were ten or fifteen cents cheaper than "white" tickets, and climb their own set of stairs to their own special section of the balcony.

After the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed, making Jim Crow laws illegal, some of the old habits were allowed to linger for a period. Both windows in the cashier's booth at the Shoals remained open, and for a while she continued to sell cheaper tickets at the side window. In theory, any black person could pay more and sit downstairs, and any white person could pay less and sit upstairs. Today the balcony is closed and has been for years; everyone sits downstairs, in fewer and wider seats, generally watching worse movies for more money.

In fact a theater like the Shoals is little more than a relic now, and everyone knows this, including the subsequent owners, who have tried to bring some aspects of the building "up to date" and in doing so have eliminated whatever inclinations toward beauty, monumentality, or eccentricity that may once have been in the design. The only movies the Shoals shows now are bland items such as Meatballs and Disney comedies, and a lot of the older kids wouldn't be caught dead there. Their turf is the strip on the outskirts of town where all the shopping centers and one enormous shopping mall are located.

And that is where the other movie theaters are, the brand new ones whose auditoriums have the feel of the insides of cheap jewelry boxes, where I saw Moonraker , a couple of sex films, Dracula , and The Muppet Movie in late July. As a rule, the people I know in Florence who see movies today watch

Shoals Theatre, Florence, Alabama, July 1979, eight months before closing

them either out there, in those frigid space stations that are as strictly utilitarian as circus tents and offer even less of an invitation to linger after the show, or on their TV sets at home. (Cable TV, I should add, is very popular.)

I suspect that most American audiences in the 1980s will be watching films either in homes or in shopping malls. What's particularly disturbing about this is that homes and shopping malls are beginning to resemble one another, along with the movies and the audiences inside them. The separate forms of social behavior that we associate with film and television are also starting to break down as the two media become increasingly difficult to differentiate, thanks in part to such expensive toys as Betamaxes and Advent screens. The arsenals of new communications equipment, which are currently being paraded before us like sophisticated armaments, indirectly yet unmistakably testify to the poverty of what we have to communicate. By trusting ourselves less, we wind up trusting the machines more. And because of these machines, word-of-mouth news travels more slowly these days, as though it were creeping from one petulant medieval stronghold to another—in striking contrast to the sixties, when certain kinds of news traveled like wildfire.

It is estimated that nearly half of all the retail business in the United States today is transacted in approximately 18,000 strip and enclosed shopping com-

plexes known variously as plazas, centers, and malls. They occupy over two billion square feet, employ more than 4.5 million people, represent $60 billion in investments, and their rate of failure over the past twenty-five years is said to be less than one percent.[*]

A study conducted at Temple University indicates that malls are the most popular gathering places for teenagers in the United States. In a controversial paper presented to the Popular Culture Association, Richard Francaviglia compared malls to amusement parks such as Disneyland. William Severini Kowinski expands on this notion by describing malls as "the feudal castles of contemporary America."

By keeping weather out and keeping itself always in the present—if not in the future—a mall aspires to create timeless space. Removed from everything else and existing in a world of its own, a mall is also placeless space.

An article in the socialist magazine Dollars & Sense points out that in recent years the U.S. Supreme Court has twice ruled in separate cases that malls are not public places where citizens can express their views, distribute leaflets, or congregate freely—unlike the old town squares.

To keep people inside the mall and encourage them to see shopping as entertainment, designers attempt to create a "carnival" atmosphere. Once inside a center, shoppers have few decisions to make. Corners are kept to a minimum so the customers will flow along from store to store, propelled, as the developers say, by "retail energy." Said one observer of mall design, "The mirrors, the music and the sound of rushing water create a sense of distortion. There is never a clock to remind one of the world outside the mall."

I think this is a pretty fair description of most of the cinema today. Both films and shopping malls function as media that aim at producing and controlling their own notions and measurements of space and time, designed to supersede all others. They offer themselves to us like self-contained planets, not tools to assist us anywhere else in the universe. Which suggests that we may be losing our marbles.

In these terms, Apocalypse Now —which I saw twice last month in New York—is a $30 million shopping mall, offering Michael Herr's Dispatches as well as Conrad's Heart of Darkness in the bookstore, The Doors and Wagner in the record and tape shop, Marlon Brando and Dennis Hopper in the snazzy nightclub, Playboy, lime, Rolling Stone, and Reader's Digest at the news-

stand, fancy roast beef and plain rice at the fast-food restaurant. To make sure that all of this goes down well, a clever pattern of continuous percussion and exotic jungle noise is pumped seductively into our ears like Muzak, controlling our inner rhythms and emotional temperatures while helping to screen out all vestiges of the outside world, including Vietnam.

To refer to such an all-purpose marketing and environmental complex as a personal form of self-expression, and to try to reduce or elevate this expression to a political statement of any sort, is merely to become a blind man in relation to Francis Coppola's elephant—and perhaps part of the film's promotional campaign in the bargain. In order to confront anything like the whole package (which is so much bigger than we are) one first has to acknowledge the presence of a complex pleasure machine, loads of fun, programmed to stimulate and then gratify as many opposing viewpoints as possible. This machine has nothing to do with Vietnam.[*] It is designed to appeal to good ole boys who kill gooks for the fun of it as well as to pacifists, liberals, blacks, whites, moderates, fascists, conservatives, humanitarians, racists, misanthropes, novelists, avant-garde filmmakers, rock and drug enthusiasts, and literature professors—all of whom are designed, in turn, to feel that it's a movie made just for them.

In the same context, what about homes, which are the only spaces we have left once we've rejected public life for a private boat ride through Coppolaland? Writer-director George Romero hits on a parodic relationship of home to shopping mall in the first two parts of his horror trilogy, Night Of The Living Dead and Dawn Of The Dead , by passing directly from the home as fortress to the shopping mall fortress as home. An alternative version of this interchange—the home as shopping mall—can easily be imagined if one starts with either of Hugh Hefner's Playboy Mansions as a model.

Having outlined such a deprived and limited future, I would like to cite a couple of things that still make me hopeful, in spite of everything. Both of these things signal the potential return of the active audience, in contrast to the passive, refrigerated, cut-off, narcissistic sensibilities that so many recent movies and movie theaters take (or ask) us to be. And both imply (albeit somewhat subversively in the present context) a community of common interests inside a theater, rather than a set of separate, elegantly upholstered masturbation stalls.

Decentered, nonprivileged space and a crowd of people contriving to reclaim what is rightfully theirs is what both these things are about. One of them is my favorite film, Playtime , made by Jacques Tati in the sixties,

which I saw first in 1968 as an American tourist in Paris. The other is an event created by an audience around a film called The Rocky Horror Picture Show , an event that has been occurring and evolving in the United States over the past three years.

Playtime was made twelve years ago, although as a practical tool for learning how to cope with the hideous world that we're building it is only beginning to be understood. When I screened it for 150 college students in San Diego two years ago, I was pleased to discover that many of them had less trouble understanding its basic principles than most film critics did when the movie first appeared—perhaps because they had fewer preconceptions about film comedy. Turning us all into tourists as it charts the movements of a group of Americans through a studio approximation of Paris, Playtime implies that empty space becomes alive (and curved) once it assumes a social function—and that the shortest distance between any two supposedly unrelated individuals within the same public space is comedy.

The film's strategy, lesson, and advice are the same: It directs us to look around at the world we live in (the one we keep building), then at each other, and to see how funny that relationship is and how many brilliant possibilities we still have in a shopping-mall world that perpetually suggests otherwise; to look and see that there are many possibilities and that the play between them, activated by the dance of our gaze, can become a kind of comic ballet, one that we both observe and perform as we navigate our way through Paris's imprisoning patterns, reflections, and deceptions.

By connecting our observations with our performances as observers, Tati returns us to the real world, as he does again in Parade . He doesn't pretend, like Disney or Coppola, to give us anything better. Instead he helps us to become a better audience by presenting us precisely with our social predicament as spectators, and then trying to show us how we might become partners in and through that experience.

Much the same could be said for the event generated by a mainly teenage audience around showings of The Rocky Horror Picture Show in more than two hundred cities across the United States. (I'm told that the fad has even passed through Florence, though not, alas, when I was there.) As an amateur of this curious phenomenon, one who has witnessed only three performances at the 8th Street Playhouse in New York, I cannot claim to be qualified to discuss the movement as a whole. But I can't deny, either, that my three visits were all exhilarating experiences.

Both the film and the stage musical on which the film is based (I first encountered them while living in London four and five years ago, respectively) describe the initiation of an ingenuous American couple into the bisexual joys practiced in a haunted house by English denizens of Grade B horror and science fiction films. (The crossovers between England and America are pos-

sibly as intricate here as those between female and male.) A distanced theatrical narrative that is interrupted repeatedly by a narrator and bracketed by self-conscious film references, the movie began to be appropriated spontaneously about three years ago by isolated members of an audience that attended regularly the midnight screenings of the film in Greenwich Village.[*]

Their appropriation can be seen as an unconscious yet authentic act of film criticism, one that returns in-the-flesh theatricality and confrontation to a flashy work that needs them. Some fans fill the pauses in the film's dialogue with wisecracks, many of them retained from one show to the next and recited in unison. Other habitués get themselves up, often in drag, to resemble the main characters and then mimic the onscreen performers' gestures, standing beneath the screen and in the aisles, while friends spotlight their actions with flashlight beams. Props are used; rice is thrown during the wedding sequence, and water pistols and umbrellas are sometimes brandished to accompany the subsequent rainstorm. These rituals and others have gradually developed into a richly elaborated, multifaceted "text" in which the film itself is only the ostensible centerpiece; it is not always the precise center of attention.

At a Rocky Horror midnight show about a week ago I met a couple of proud veterans, each of whom had seen the film nearly three hundred times. Two women were present to play the Tim Curry part of Dr. Frank N. Furter (the leading transsexual character, who appears in drag), along with more than a dozen other performers, many of whom went through several elaborate costume changes to match their screen counterparts. One of the women playing Frank was a New York regular who told me she had seen the film fifty times; the other, a young black woman from Chicago, took over the role for a few guest appearances toward the end.

Despite some competitive divisions and hierarchies within this cult, the spirit of the shows I have attended has been markedly democratic and non-elitist. No one is treated like an outsider; anyone, theoretically, can make her or his own contribution to the "text," which is in a state of continual change and refinement.

What is it about these shows that is so energetic and exciting? Above all, I think it is the experience of a film's being used by people as a means of communicating with one another—not after the film has ended, but while it is still in progress. I think we could learn a great deal about our own favorite movies if we knew how to use them that way.

Some commentators have found the implications of this practice to be

fascistic and mindless. The adoption of such a movie (or any movie) as a sacred text to be memorized, recited as a catechism, or elaborated upon as in a religious commentary offends their sense of propriety and aesthetics. Without wishing to idealize this ritual, I would like to point out that it is much more appealing to experience it than to hear or read about it. (As a group activity, the closest parallels that spring to mind are jam sessions among jazz musicians and responses from congregations to sermons at black revival meetings.) With its characteristic open-mindedness, Newsweek reports that "Some middle-aged viewers are disgusted by the film's blatant transsexuality; others merely dislike it."[*] Still others, less self-defensive, have simply enjoyed the show, recognizing at once how fundamentally innocent it is. Or perhaps I should say innocently perverse, like the rest of filmgoing.

What most of the objections fail to acknowledge is that the meaning of any work of art is in part bound up in its social function. The Rocky Horror phenomenon—not, I should stress, the film—is a work of art whose audience and creators are essentially one, grouped around a shared irony about sexual roles and social taboos that remains as a legacy of the sixties, and whose social function is largely to bring together strangers and open up new channels of communication between them. I like it because it resurrects moviegoing as a communal event, making one proud, not embarrassed, to be sitting next to other people in the dark.

Station Identification II

Yes, I need the Conquistador; and yes, I mistrust and sometimes despise him. At eight and ten, while watching On Moonlight Bay , I knew that I needed him, and I loved him, too; I'm sure that I even loved my servitude. Now I question how well he fulfilled his duties as a foster parent. I can't deny that he kept me entertained and even busy, but whether he's worthy of the sort of unquestioning admiration due to, say, Nigger Jim is a different matter. Right now I'd say that it was Uncle Remus who came closer to describing—or executing—his peculiar talents.

Now there was a traumatic experience. Walt Disney's Song of the South , according to my real parents, was the first film they ever took me to (probably during its initial run at the Princess, April 8–11, 1947, not long after I turned four and less than a year after Bo taught me how to read). A terrifying cartoon briar patch that might have been hatched in the brain of a Sade; the disquieting, chirpy-rasping voices of Br'er Fox and Br'er Rabbit, and the psychotic, molasses-slow, dumbkiller ground bass of Br'er Bear; and the trauma of Daddy's leaving for Atlanta—made even more real by the fact that Bobby Driscoll's name in the movie was Johnny. So what if the main plot took place on a plantation in the Old South? In all basic respects it was the same world as here and now. As Jacques Rivette once observed, Griffith's Intolerance —which Stanley went to see with his mother Anna in Little Rock when he was in the first grade, taking the streetcar all the way from North Little Rock—has more to say about 1916 than about any of the historical periods it depicts. In the same way, Song of the South is about 1946, not long after a time when many Daddys were away.

Most traumatic was the departure of Uncle Remus, "fired" by Mommy for

telling Johnny stories that taught him how to think and behave while Daddy was away, poor old misunderstood Uncle Remus, packing all his belongings in a bandana that he tied to the end of a pole, then boarding a wagon bound for Atlanta, and Johnny running across the field after him, screaming, "Come back, Uncle Remus, come ba-a-ack! " and failing to notice the mad bull preparing to charge him. Then, waking from a coma, Mommy, Daddy, and the entire plantation staff—the whole world, really—crowded around his sickbed (a bit like the whole Duke Ellington band in silhouetted chiaroscuro, crowded around Fredi Washington's deathbed at the end of Dudley Murphy's 1929 Black and Tan ), as he continues to call hysterically for Uncle Remus (just a junkie, really, like Little Nell and Marcel Proust rolled into one) until Daddy finally fetches Uncle Remus, bringing him right to Johnny's bedside, which immediately revives him. What could possibly be more traumatic than losing Uncle Remus?

Movies were my Uncle Remus, and they didn't prevent my being gored by bulls—not even once. At best they could revive me afterward. Daddy and Bo were the bosses who owned the bull and hired Uncle Remus, and the Conquistador told Bo and Daddy what to do. My greatest ambition was to do what they did, to grow up and do what the Conquistador told me to do. Consequently, I kept on running across fields and getting gored by bulls, and good ole Uncle Remus just kept on reviving me.

So how else can I feel today but ambivalent? The Conquistador paid for Putney, Bard, and Stony Brook, most of Paris, both my novels in all their drafts, and even part of this book, too. After a while it gets to the point where you want to be gored—it's so dramatic! exciting! And it paves the way for Uncle Remus to make his grand comeback, to soothe your wounds so nicely. Just like any ordinary night at the movies.

So let's be clear about this; the villain-of-the-piece is neither the bull nor Uncle Remus (either of whom could be booked through central casting) but the Conquistador, who keeps them both operational, makes them play their assigned parts, calls all the shots, and directs all the shots at me. I have two choices: to do battle with him (shield myself from his shots and/or return a volley of my own) or to surrender. The same choices that anyone has at his or her favorite movie theater, at any given moment. Isn't it just being alive? Both options are very tempting. Either one is fatal.