Representational Practices in Life of an American Fireman

A full appreciation of Life of an American Fireman requires a shot-by-shot analysis. In shot 1, a dream balloon shows the fire chief thinking of a mother

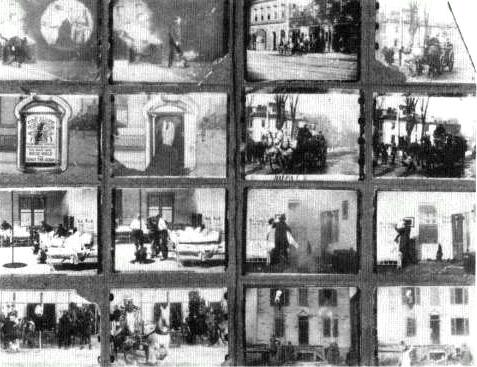

Frames from Life of an American Fireman—two per shot—except for shot 5

(one frame), shot 6 (3 frames), and shot 7, which is not represented.

and child (a composition with religious overtones), possibly his family. The dream balloon fades away and the fire chief exits. This shot is spatially and temporally independent from the rest of the film. Shot 2 is a close view of a hand pulling down the arm of the fire alarm. There is a temporal overlap at the end of shot 2/beginning of shot 3 as the firemen, at first asleep, jump out of bed in response to the alarm. The firemen, on the second floor of the firehouse, put on their clothes and jump down the fire pole until only one is left. Shot 4, the interior of the engine house with its vaunted interior hitch, was actually filmed in an elaborate outdoor set: the floor is mostly grass. The scene begins as the horses are quickly harnessed to the engines. After a few moments, the firemen come down the fire pole. Here, a more substantial temporal overlap with a redundancy of action is employed between shots 3 and 4. The end of shot 4/ beginning of shot 5 employs yet another overlap. Shot 4 ends with the fire engine racing off forward right. Shot 5 begins with the firehouse doors opening and a fire engine exiting off right. In shots 3, 4, and 5, Porter shows everything

of dramatic interest occurring within the frame. This results in a redundancy of dynamic action—the slide down the pole, the start to the fire—effectively heightening the impact of the narrative. At the same time, the repeated actions clearly establish spatial, temporal, and narrative relationships between shots. It is, as Porter realized, a kind of continuity, but one radically different from the continuity associated with classical cinema.

Shot 6, "Off to the Fire," is a conventional rendering of the fire run and relies on the quantity of fire engines to impress its audience. Narrative consistency is sacrificed to spectacle. In shot 7 a fire engine races by a park. As the fire engine approaches, a pan follows the action, focusing on James White, who jumps off the vehicle in front of a burning building. Again, the moving camera suggests the immediacy of a news film. Convention and narrative continuity rather than continuity of action establish the relationship between shots 7 and 8. Shot 8 shows a bedroom interior as the woman gets out of bed, staggers to the window, and is overcome by smoke. The fireman breaks in the door, enters, and then breaks out the window, where a ladder appears. After carrying out the woman, he immediately returns for the child hidden in the bed covers. The fireman leaves with the child, but quickly returns again with a hose and douses the flame.

Shot 9, using virtually the same camera position as the concluding section of shot 7, shows the same rescue from the outside. The woman leans out the window (in shot 8 she does not lean out the window; however, the gesture is identical) then disappears back inside; the fireman brings her down the ladder; she tells him of her threatened child; he races back up the ladder and returns with the child. As the mother and child embrace in a tableau-type ending, the fireman again ascends with the hose. Shots 8 and 9 show the same rescue from two different perspectives. The blocking is carefully laid out, and continuity of action is more than acceptable. The activities in shot 8 have their counterparts in shot 9 as people move back and forth from inside to outside: the succession of complementary actions tie the two shots together—something Porter did only twice in How They Do Things on the Bowery . While on one level these two shots create a temporal repetition, on another level they each have their own distinct and complementary temporalities, which together form a whole. When the interior is shown, everything happening inside unfolds in "real" time while everything occurring outside is extremely condensed. The reverse is true when showing the rescue from the exterior. In keeping with theatrical conventions, whenever actions take place off-screen, time is elided.

This complementary relationship between shots is a kind of proto-parallel editing involving manipulation of the mise-en-scène instead of manipulation of the film material through decoupage, and manipulation of time over space. While Life of an American Fireman uses familiar spatial constructions, its temporal construction differs radically from matching action and parallel cutting,

which audiences would see only six years later in such Griffith films as The Lonely Villa (1909). The Lonely Villa utilizes a representational system dominated by the linear flow of time, an accomplishment made possible by fragmentation of the mise-en-scène and a rapid shift in shots as the narrative moves back and forth between locations. Life of an American Fireman remained indebted to the magic lantern show, with its well-developed spatial constructions and an underdeveloped temporality. By showing everything within the frame, Porter was, in effect, making moving magic lantern slides with theatrical pro-filmic elements. Shots are self-contained units tied to each other by overlapping action. Ironically, Life of an American Fireman has frequently been praised for its fluidity and the way it condenses time through editorial strategies. The reverse is often true: the action is retarded, repeated.

Life of an American Fireman contains a series of fascinating contradictions. The frontal organization of pro-filmic elements occurring in most scenes is briefly broken in shot 7 by the sweeping camera, which momentarily reveals a "continuous" off-screen spatial world that exists outside the static rectangle of the camera frame. The pervasive presentationalism, indebted to traditional stage practices, is again contradicted by the "omniscient" camera, which views the same actions from two (and if two, why not three, four, or five?) different perspectives. Shots are constructed as discrete, independent units even as they are made subservient to an overall narrative. Having developed strategies that superseded the exhibitor's role as editor, Porter continued to draw upon his own background as an exhibitor by combining scenes of four different fire departments (just as an exhibitor might show a Passion Play using films from four different producers). This syncretic film is caught somewhere between the presentation of simulated reality and a fictional story. This story, which exists to the extent that the fire chief and his vision of wife and child resonate throughout subsequent scenes, is periodically sacrificed to spectacle. The tentative story, therefore, could either be ignored or developed by the showman as he was inclined. As if to compensate exhibitors for their lack of editorial opportunities, the film offered them great latitude in presenting the film. Contradictions such as these inspired Noel Burch's description of Porter as a two-faced Janus who looks backward and forward in time.

The narrative and temporal organization that Porter made explicit in How They Do Things on the Bowery and Life of an American Fireman can be found in many of his later films, including Uncle Tom's Cabin (1903), The Great Train Robbery (1903), The Ex-Convict (1904), The Watermelon Patch (1905), The "Teddy" Bears (1907), and Rescued from An Eagle's Nest (1908). Other filmmakers, notably those working at Biograph, followed Méiès' and Porter's lead in films like Next! (photographed November 4, 1903), A Discordant Note (June 26, 1903), The Burglar ( August 21, 1903), Wanted: A Dog (March 1905) and The Firebug (July 1905). English films like G. A. Smith's Mary Jane's Mishaps

(1903) and Cecil Hepworth's Rescued by Rover (1905) have similar temporal constructions, while Méliès continued to use overlapping action in Le Voyage à travers l'impossible (1904) and Le Mariage de Victorine (1907). Porter and his contemporaries were working within a cultural framework that made this mode of narrative organization intelligible, even "natural," to their audiences.

The narrative procedures in Life of an American Fireman involve structures occurring in different cultural forms at different times. Sergei Eisenstein used brief overlaps in October (1927), but these broke the "seamless" linear continuity of shots that had become part of classical narrative cinema. The procedure may be similar to Porter's, but its function was completely different, for Porter's strategy was to create a greater degree of continuity than had theretofore existed.

The parallels between Life of an American Fireman and medieval French poetry —chanson de geste —are extremely provocative. Erich Auerbach, in examining Chanson de Roland and Chanson d'Alexis , notes that "in both we have the same repeated returning to fresh starts, the same spasmodic progression and retrogression, the same individual occurrences and their constituent parts."[16] The description of Roland's death (laisses 174-176) is one example of this narrative technique:

174

2355 Roland feels that death is overcoming him,

It descends from his head to his heart.

He ran beneath a pine tree.

He lay down prone on the green grass.

He places his sword and his oliphant beneath him.

2360 He turned his head toward the pagan army:

He did this because he earnestly desires

That Charles and all his men say

That the noble count died as a conqueror.

He beats his breast in rapid succession over and over again.

2365 He proffered his gauntlet to God for his sins.

175

Roland feels that his time is up,

He is on a steep hill, his face turned toward Spain.

"Mea culpa, Almighty God,

2370 For my sins, great and small,

Which I committed from the time I was born

To this day when I am overtaken here!"

He offered his right gauntlet to God,

Angels from heaven descend toward him.

176

2375 Count Roland lay beneath a pine tree,

He has turned his face toward Spain.

He began to remember many things:

The many lands he conquered as a brave knight,

Fair France, the men from whom he is descended,

2380 Charlemagne, his lord, who raised him.

He cannot help weeping and sighing.

But he does not wish to forget prayers for his own soul,

He says his confession in a loud voice and prays for God's mercy:

"True Father, who never lied,

2385 Who resurrected Saint Lazarus from the dead

And saved Daniel from the lions,

Protect my soul from all perils

Due to the sins I committed during my life!"

He proffered his right gauntlet to God,

2390 Saint Gabriel took it from his hand.

He laid his head down over his arm,

He met his end, his hands joined together.

God sent His angel Cherubin

And Saint Michael of the Peril,

2395 Saint Gabriel came with them.

They bear the Count's soul to Paradise.[17]

The laisse is the primary unit of production for chansons de geste ; its equivalent is the shot in turn-of-the-century cinema. Just as Porter showed the same rescue from two different perspectives, so the author of Chanson de Roland used laisses similares to describe the manner in which Roland dies. Certain actions are reiterated: Roland feeling that his time is up (lines 2355 and 2366), beating his breast (2364 and 2369) and offering his gauntlet to God (2365 and 2373). Other actions or speech in laisse 174 are omitted in 175 and new ones added. Both Porter and the chanson's author made use of this technique at climactic moments in their narratives.

Overlapping action, which Porter used throughout Life Of an American Fireman , is frequently encountered in chanson de geste as well, for instance at the end of laisse 164 and beginning of 165:

He [Count Roland] suffered such pain that he could no longer Stand,

Willy-nilly, he falls to the ground

The Archbishop said: "You are to be pitied, worthy knight"

When the Archbishop saw Roland faint,

He suffered greater anguish than ever before.[18]

These congruencies are not simply representational coincidence, but are intimately related to parallel modes of production. Jean Rychner has explored the complex relationship that existed between the performers who sang the epic

poems and the surviving chansons . He concludes that "all the good singers are also improvisers; they created their songs themselves, and, when they did not create them properly speaking, they knew how to combine the songs of others, how to condense several poems into one, how to modify, complete and amplify.[19] The chanson de geste , like the early film program, was an open work, subject to the jongleur's manipulation—with the manipulation of laisses the primary level on which this was accomplished. New laisses could be added or whole sections could be omitted. Elaboration of narrative was not achieved within a simple linear time line but through repetition. Furthermore, with such a system of production, overlapping narrative was an effective way to relate a new or different laisse to the existing narrative.

There are other parallels. Audiences for Chanson de Roland and Life of an American Fireman already knew the story they were seeing and/or hearing. Much of their enjoyment came from relating the individual presentations to the known narrative: appreciation was based on the audiences' ability to judge skill of execution and effectiveness of representation in comparison to previous presentations. Correspondingly, the film producer or jongleur relied on iconographic images, gestures, and phraseology in the creation of scenes and laisses .[20] Images and forms of expression were both highly conventionalized from the perspective of the producer as well as of the audience.

Chanson de Roland and Life of an American Fireman occupy similar places in the respective developments of European literature and the American screen to the extent that both forms were moving toward a new mode of production in which a work had closure and there was a single "author." This was achieved in literature, of course, by a movement toward the written text. Both works are exceptions within their respective forms because of "the unity of subject and internal cohesion,"[21] which placed them at the forefront of these developments. This exploration of convergences, however, is not an attempt to elevate Life of an American Fireman to the status of Chanson de Roland as a work of cultural significance. Chanson de geste developed over a period of centuries and was a major form of cultural expression. The cinema in 1903 was still only one of many forms of popular culture, and the circumstances that conditioned this kind of narrative structuring were short-lived. The Edison Manufacturing Company bore little resemblance to a medieval court: cinema, driven by fierce competition, continued its rapid transformation, quickly developing strategies more consistent with narrative techniques found in other contemporary media, particularly the use of a linear time line. The mode of representation used by Griffith only ten or fifteen years later would be compared to that of Charles Dickens.[22] Yet Life of an American Fireman is emblematic of a crucial moment in film history. It signaled a further shift in the editorial function from exhibitor to production company and a tendency toward producing larger units (i.e., longer and therefore more complex films). Although this can be attributed in some

degree to industrial efficiency, maximizing profit, and the structure of American industry, such pressures were increased exponentially by a new level of narrative organization, often called "the story film." Because story films could be more effectively produced by an organization having greater creative control, the role of the filmmaker was fundamentally constituted as we conceive of it today.