11

As Cinema Becomes Mass Entertainment, Porter Resists: 1907-1908

Edwin Porter and the Edison Manufacturing Company found themselves operating within a dynamic, rapidly changing industry. The year 1907 was a key turning point in cinema's history as pressures created or magnified by the nickelodeon boom transformed screen practices on almost every level. Finally, by mid 1908, cinema had become a form of mass communication: "a process in which professional communicators use mechanical media to disseminate messages widely, rapidly and continuously to arouse intended meanings in large and diverse audiences in attempts to influence them in various ways."[1] Such a transformation involved changes in the methods of representation, film production, exhibition, reception, and distribution. Yet Porter barely participated in this process. As a result, his standing and the standing of his films were on the wane. Thomas A. Edison, in contrast, began to assume a new and more powerful role, using litigation victories on his motion picture patents as the basis for this renewed influence.

The End of the Nickelodeon Frontier

The nickelodeon boom was coming to an end by late 1907. Towns in most parts of the country had at least one motion picture theater. Nickelodeon managers were operating within a competitive environment that required them to show more and newer films and to change programs more frequently. Expenses therefore rose. Since most of these improvements made the shows last longer, fewer patrons could be admitted. Since admission remained at five cents, box-office grosses declined. With expenses increasing and revenues decreasing, many small theaters could not seat enough customers to survive. Economies of scale, upgrading and expansion of facilities, and elaboration of exhibition practices

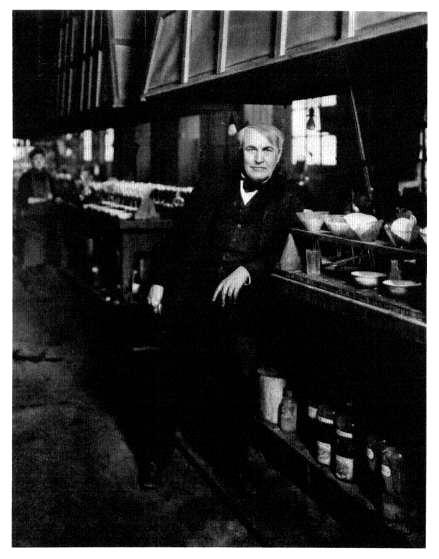

Thomas A. Edison in 1906.

became necessities for many showmen. Larger theaters spread operating expenses over more seats and were able to offer a superior show at a lower cost per customer.

A brief, sharp depression, started by a financial panic in October 1907, intensified competition and the process of rationalization both within the moving picture field and between different parts of the amusement industry. By late

November Film Index reported: "All must admit that there has been a stringency in the moving picture field as far as patronage is concerned. It would be an extraordinary thing had that field alone withstood the 'squeeze.' Every line of business in the country has felt it to a more or less severe extent and none more so than the theatrical."[2] Vaudeville houses in big cities drew fewer customers, reducing their profitability. In New York, Keith & Proctor responded by converting many of its vaudeville theaters to moving pictures.

Manhattan's downtown section became a center for motion picture exhibition. William Brady acquired the 1,200-seat Alhambra Theater on Fourteenth Street and reopened it as a motion picture house, the Unique, at the end of 1907.[3] People had predicted that this change would adversely affect neighboring vaudeville and burlesque houses. These expectations proved correct. By late June not only Keith's Union Square Theater but the Dewey, acquired by William Fox, and Pastor's had been converted to motion picture shows. On a single block between Broadway and Third Avenue on Fourteenth Street, there were five picture houses. Competition was so intense that Variety called it "the Battle of 14th Street." To attract patronage, Pastor's offered a four-reel, one-and-a-quarter-hour program. Unable to compete, the Miles Brothers closed their Fourteenth Street storefront theater at the end of June.[4] Across the country, managers were using films to replace vaudeville or fill a house that would have otherwise been dark.

Opportunities for safe investments by small-time entrepreneurs were giving way to competition and big business not only among exhibitors but among the film exchanges as well. By December 1907 Carl Laemmle had opened exchanges in Evansville, Indiana; Memphis, Tennessee; and Council Bluffs, Iowa.[5] Less than a year later, he had six offices outside Chicago.[6] William Swanson bought out his partner, James H. Maher, and opened a new exchange in New Orleans in September 1907; a third Swanson exchange was started in St. Louis two months later.[7] Similar moves were made by other prominent renters.

By the end of 1907, a web of film exchanges stretched across the country. Subsequent growth for these companies was no longer based on the exploitation of new territories. Superior service, aggressive promotion, and/or lower prices were needed to maintain a competitive position and to win customers away from rival businesses. During the general financial panic, however, prices were slashed relentlessly. One trade journal called it a "renters' panic":

From reports of progress from all over the country it is very evident that something must be done now, as regards the competition among film renters. The best of things do at times outgrow their usefulness, and the healthy influence of competition has been worn threadbare in this case; it is no longer the healthy competition which is said to be "the life of the trade," but a menacing, detrimental scramble for all that is within reach, without regard for the ordinary ethics of a self-respecting commercial man.

Yes it is a panic. Why is it that a renter sends emissaries around the showmen

soliciting business, not at any fixed price but at any price at all, just so it is lower than the other man's?[8]

Less efficient exchanges operated at a loss or cut corners. To avoid purchasing new prints, they sent exhibitors "junk"—worn-out prints that should not have been screened. Short on cash, they sometimes paid film manufacturers with bad checks.[9] Some unscrupulous renters—notably the 20th Century Optiscope Company—made or purchased illegal dupes, depriving the original producers of significant revenue.[10]

Although established producers continued to make good profits throughout the fall of 1907 because of the continued shortage of films, they felt uneasy about the future. As a new generation of successful renters looked for growth opportunities within the industry, they followed the leads of Vitagraph, Kalem, and Essanay by moving into production. William H. Goodfellow, owner of the Detroit Film Exchange, started the Goodfellow Manufacturing Company. In St. Louis, Oliver T. Crawford, who owned several exchanges and many theaters, moved into production. His company's first film was of the International Balloon Races in October. Comedies and dramatic films were to follow shortly.[11] The Actograph Company was taking actualities by August and was ready to make fictional subjects three months later. One of the enterprise's assets was the dog Mannie, which had starred in many previous Edison films.[12] Looking toward the future, established producers realized that unregulated competition assured eventual overproduction, falling prices, and lower profits.

Established motion picture manufacturers were caught between aspiring production companies on one hand and Edison litigation on the other. If the validity of Edison's patents was upheld, they, too, would be treated as upstarts. After Edison's partial victory against Biograph in March 1907, the inventor's lawyers reactivated a suit against William Selig and began to build a case against Vitagraph. Edison hired George E. Stevens away from Vitagraph, where he had worked as a stage manager between October 1906 and April 1907. Stevens provided Edison's lawyers with evidence that proved Vitagraph had been using the infringing Warwick camera and had subsequently converted to the Demeny beater camera made by Gaumont in an attempt to circumvent Edison's patents.[13] Six years later, Smith was to recall, "We were very perturbed and disturbed over the fact that they had gotten this evidence and shortly after that suggestions were made to us that we could get together with the Edison Company and pay a license, the probability was that some sort of agreement could be reached, whereby we could proceed with our business in a state of peace and security, with the assurance that we would be no further disturbed in the development of the art, and the investment of our money."[14] Smith's sentiments were echoed by George Spoor and other producers.[15] When an injunction was entered against Selig on October 24, 1907, it was clearly time for the manufacturers to reach an agreement with Edison.[16] Such an agreement, moreover,

could provide the basis for an association that might regulate aspects of the industry for the benefit of its members.

The Formation of the Association of Edison Licensees and the Film Service Association

The "general dissatisfaction with conditions" led to a meeting of manufacturers in New York on November 9, 1907. George Spoor and William Selig attended from Chicago, as did the leading New York producers and importers.[17] A week later, this group and owners of many of the country's leading film exchanges gathered in Pittsburgh "to discuss matters of vital importance for the regulation and improvement of existing business conditions."[18] The renters met among themselves and formed the United Film Service Protective Association "for the purpose of working in cooperation with the manufacturers, importers, jobbers and exhibitors of the films and accessories to improve the service now furnished the public, to protect each other in the matter of credits and all other conditions affecting our mutual welfare, and in general to take such action as will be appropriate to improve conditions of the trade."[19] They adopted a platform that prohibited exhibitors from subletting or "bicycling" prints among several theaters, a practice that wore out their goods and reduced the number of paying customers. To assure themselves adequate profits, they established a minimum rate for service. To make it more difficult for new exchanges to begin, they eliminated sale of second-hand film. Prints were to be retired after a designated period of time and returned to the manufacturer. To prevent small or new exchanges from joining the association, an initial membership fee of $200 was imposed and thereafter raised to $5,000 with a waiting period of one year before the newcomer's membership could be activated.

The renters planned to form an alliance with a separate, but coordinated, organization of manufacturers; this group would marginalize if not eliminate nonmember competitors. Although the renters came to ready agreement at the Pittsburgh convention and subsequent meetings in Chicago and Buffalo, the manufacturers and importers encountered much greater difficulties, for Edison was determined to take control of any organization that might emerge. While the producers recognized that Edison's patents could provide a valuable under-pinning for the organization, the terms had to be negotiated. Moving Picture World later reported: "It is claimed that the motives which led to the combination of interests between the manufacturers were 'ninety-nine parts commercial and one part legal, the legal aspect being only a stepping stone to accomplish the prime object of placing the business on a substantial footing for the ultimate benefit of all concerned.' "[20]

Edison and Gilmore decided to offer licenses to only seven manufacturers and to exclude importers like George Kleine, Isaac Ullman, and Williams, Brown & Earle. Licenses were designated for Biograph, Vitagraph, Lubin, Selig,

Pathé, Méliès, and Kalem. The inclusion of Kalem was supposed to mollify Kleine. Essanay was viewed as a backup: if Biograph failed to join, Spoor and Anderson would be given a license. Biograph was the source of much difficulty. Since its motion picture patents had been recognized by the courts, it wanted this to be reflected in the new organization. This Edison refused to do. After much hesitation, Biograph finally refused to join, thus enabling Essanay to receive a license.[21] Edison executives planned to permit these seven licensed manufacturers to operate if they paid a penny-per-foot royalty on the film they used. While this tribute was acceptable to American manufacturers, Pathé Frères insisted on only half that amount. Edison held a legal advantage, but Pathé held the upper hand commercially. Without Pathé's participation, no association was possible. Pathé had its way.[22]

A formal agreement, effective March 1st, was finally reached at the conference of film renters and manufacturers in Buffalo on February 8th and 9th. Variety noted that "the American moving picture trade was organized into a compact, cohesive system of manufacture and distribution which, it is promised, will revolutionize the business."[23] This was accomplished through the mutual support of the Association of Edison Licensees (the production companies) and the renamed Film Service Association (the renters): they were conceived of as allied, equal, and independent organizations. Film Service members agreed to purchase films only from the Edison licensees, while the licensees were to sell only to the members of the Film Service Association (FSA). Several exchanges faced difficult choices. O. T. Crawford, the Actograph Company, and the Miles Brothers ceased their production activities and joined the FSA. Mannie, the Edison dog, did not return to the screen. William Goodfellow, however, kept his exchange out of the combination so he could continue his filmmaking activities. Renters were further prohibited from purchasing a manufacturer's business or license, a rule that was later tested in the case of the Méliès company.[24]

To strengthen the position of the licensees, the Edison Company signed an agreement with George Eastman. This required the licensees to buy all their raw stock from Eastman Kodak; in return, Eastman would not sell to newcomers, including American manufacturers outside the trust, with the sole exception of Biograph. Vitagraph was unhappy that Eastman had not limited his sales to European competitors as well. In a letter to George Eastman marked "strictly confidential," J. Stuart Blackton argued that "the only reason which could induce me to accept a license and permit Edison to make an enormous profit with the royalty would be that in doing so I would thereby keep the foreign competition out of the market."[25] With George Eastman providing the best, and for practical purposes the only, film for motion pictures in America, this agreement greatly strengthened the position of the licensees by raising barriers to aspiring domestic producers.

Licensed renting activities were concentrated in approximately 120 ex-

changes owned by 60 renters. Some of these were latecomers that were allowed to join the FSA rather than side with the opposition forming around Biograph. Renters were required to buy at least $1,200 worth of film each month. Vitagraph expected this last requirement to increase its sales by at least forty reels of film per month.[26] It also eliminated smaller exchanges that were a potential threat to more established bureaus. Exchanges were not allowed to rent to exhibitors showing unlicensed films or to undercut the schedule of minimum prices. Violation of these and other rules meant fines or expulsion from the FSA. Some restrictions—for instance, one that prohibited businessmen from acting as both renters and exhibitors—were met with skepticism and never enforced.

The Edison licensees also introduced a formal release system. During the fall, some manufacturers had marketed a new film each week but without specifying the precise day of delivery. Now individual manufacturers released a picture on a given day of the week—every week. Pathé, increasing its production rate to five reels of film per week, released films on Mondays, Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Fridays, and Saturdays. Vitagraph at first released on Thursday and later Tuesday.[27] Edison shipped prints of a new film every Thursday.[28] Others sought the most advantageous position. Designed to maximize sales, the release system ensured a steady, predictable flow of new subjects to the exchanges and then on to the exhibitors.

Although the nickelodeons were suppose to receive better service in the form of newer prints, they were the losers under the new arrangements. The announced increase was expected to force some theaters to raise their admission fees to a dime. Others would be forced to close. In Philadelphia, Harry Davis's general manager observed, "while the new agreement entered into by the manufacturers of films would probably force a number of small places out of existence, it would prove beneficial to the larger concerns."[29] Their rental costs rose as manufacturers and renters were organizing to take a higher proportion of industry revenues. Although barriers were created to deter people from entering production and distribution, no deterrent prevented them from entering the exhibition field. The agreements would initially eliminate some marginal theaters and encourage economies of scale, but the producers' goal was to maximize the number of rentees and the corresponding volume of sale. At the top, the Edison arrangement was monopolistic in intent; at the bottom, free enterprise would reign.

Laying out rules that regulated the principal components of the industry, the Association of Edison Licensees and the Film Service Association prohibited marginal film practices. The production of industrials, advertising films like those Edison made for Walkover Shoes, and special comedies like those made for Lew Dockstader was apparently no longer permitted. Local actuality subjects could not be made or handled by members of the Film Service Association,

pushing nonfiction filmmaking even further to the margins.[30] Sales of films to schools, hospitals, and amateur exhibitors would continue only under severe restrictions: films had to be at least one year old and under 200 feet in length.[31] Independent activities by exhibitors such as Lyman Howe, Burton Holmes, and Robert Bonine were theoretically banned; practically they continued in a legal twilight.

The Biograph Association of Licensees

The Association of Edison Licensees and the Film Service Association had limited ability to implement their desired regulations because important enterprises stayed outside the combination. The American Mutoscope & Biograph Company and George Kleine were not given the opportunity to join the Edison combination in a capacity commensurate with their economic or legal positions. They formed an opposing organization based on Biograph's productions and patents and Kleine's European imports and chain of exchanges. Italian "Cinès"; Williams, Brown & Earle; and the Great Northern Film Company were also given Biograph licenses to import films from abroad.[32] Altogether they offered a "regular weekly supply of from 12 to 20 reels of splendid new subjects."[33] Furthermore, Biograph announced its intention to license local domestic producers. Although it did not follow up on these threats, companies like Goodfellow Manufacturing operated in cooperation with the Biograph group.[34] The resulting "film war" was waged simultaneously on the legal front through the courts, on a commercial front through pricing and marketing strategies, and on the production front through the efficient manufacture of popular films.

On the legal front, Edison sued Biograph and the Kleine Optical Company in March for infringing on a film patent, reissue no. 12,192, that had not previously been tested in the courts.[35] To strengthen its position, Biograph acquired the "Latham loop" patent from the E. & H. T. Anthony Company for $2,500 and used it to bring countersuit against the Edison Company and its various licensees.[36] Lengthy discussions in the trade were devoted to the value of the Latham loop, which Frank Dyer regarded "as so unimportant as not to warrant serious consideration."[37] George Kleine and Biograph's Harry Marvin, in contrast, insisted the loop was essential for making films over 75 feet in length.[38] Biograph also formed an alliance with the Armat Motion Picture Company on March 21st, thereby gaining access to its patents covering motion picture projection.

"We were engaged in bitter commercial strife," Harry Marvin later explained. "We did what all people do under those circumstances. We fought the best we knew how. We belittled the possessions of our enemies, and we magnified our own possessions."[39] Between March 16th and April 30th, the Edison Company brought suit against thirty theater owners in the Chicago area and six in the Eastern District of Missouri (St. Louis) and the Eastern District of Wis-

consin (Milwaukee) for showing films produced or imported by the Biograph licensees.[40] William T. Rock, a longtime believer in patent litigation as an effective commercial weapon, was delighted. "Why, man, all they have to do is to draw up a general complaint, print fifty or a hundred copies and file suits in as many cities of the Union," he told a reporter. "This can be done at very little expense, but look at the thousands of dollars that will have to be spent by the other side in engaging lawyers and defense for all these suits."[41] Kleine, identifying the Biograph licensees as "independents," observed that these suits were attempts to drive users of independent films into the Edison circle by questionable methods. He appealed to "the characteristic feeling of stubbornness in the average American which prompts him to resent such an attempt to compel him to violate his principles of independence."[42] Accepting the argument that such actions constituted harassment, the courts prevented Edison from bringing additional suits against Kleine's customers until the principal suits were resolved. To maintain the balance of anxiety, Biograph and Armat initiated legal action against William Fox's Harlem Amusement Company and a chain of twenty Chicago theaters in late May.[43] Many companies that had joined the Edison association thinking it would bring legal peace were disappointed when the warfare intensified and the uncertainty remained.

On the commercial front, the Edison licensees and Film Service Association cut prices 20 percent to maintain their competitive position. Unaffiliated exchanges were also allowed to join the FSA at the old $200 rate[44] even as the renters' return of old films to the producers was quietly deferred.[45] While able to consolidate their initial advantage, the Edison affiliates could not eliminate the opposition. In an interview, I. W. Ullman of Italian "Cinès" admitted that his company had experienced "the forced shrinkage in our market, beginning March 2, 1908, of upwards of 75 per cent."[46] Reports reaching Frank Dyer at the Edison office, however, document the resurgence of the independents in some areas of the country. Writing in late April, Laemmle reported that "there is no denying the fact that the Independents are getting stronger day by day." He enclosed a letter from his manager in Evansville, Indiana, predicting that "this whole section is going to the independents within the next ten days if something is not done and done mighty quick."[47] The independents moved rapidly to establish their own nationwide network of film exchanges. George Kleine, who sold his Kalem Company shares to avoid conflicting interests, opened new branches until he had offices in twelve key cities.[48] Williams, Brown & Earle inaugurated a Philadelphia exchange much against their will; nonetheless, it soon proved profitable.[49] A small group of established exchanges also went over to the independents.[50]

The exclusion of many European and select American producers from the Edison ranks resulted in a serious dearth of subjects. A New York critic visited ten nickelodeons in his neighborhood and found that nine were showing the

same first-run films.[51] This was particularly notable along Manhattan's Fourteenth Street, where the Unique, Dewey, Pastor's, and Union Square theaters were "determined to have none but the newest and latest films obtainable from the Edison side."[52] The same pictures were shown in all four theaters. In July the Unique jumped over to the independents to secure fresh subjects. Other large theaters in New York and Brooklyn made a similar switch at about the same time.[53] The Dramatic Mirror reported:

Changes of service have been made both ways by theatres in different parts of the country, and such changes are bound to occur from time to time so long as the field is divided into two camps. Neither side is turning out enough new subjects to supply the entire market, and managers who do not want to give the same pictures as their neighbors, or who think they can get better service by changing, will change. In the long run the best output of subjects will prove the most profitable—that is, providing patent litigation does not wipe out one side or the other.[54]

Since the independents helped to satisfy the nickelodeons' desire for product diversity, the Edison group found it difficult to push them from the field using strictly commercial methods.

The extent to which independent films were available in the New York area was suggested by Edison's industrial spy, Joseph McCoy, who saw 515 films while visiting 106 different storefront theaters in June. Of these films, 57 had been made by the independents and the rest by Edison licensees; however, McCoy saw 133 of them at the Elite Theater in Newark, New Jersey, which showed only licensed films. Disregarding this theater, the independents provided about 15 percent of the films that McCoy saw. Of these 57 films, 15 were made by Biograph, 13 by Italian "Cinès," 11 by Gaumont, 10 by Urban-Eclipse, and 8 by Nordisk. In contrast, the Edison Company alone supplied 45 of the films viewed by McCoy.[55] Despite their small share of the film business, the independent or non-Edison combination made it difficult for the Film Service Association to maintain discipline within its ranks. Expulsions for violations would not put the guilty exchanges out of business but send them into the opposition camp, further strengthening the Biograph licensees and weakening the Edison position.

The Edison group was internally disorganized, with considerable animosity existing between rival FSA exchanges. Despite its recently exposed duping activities, the 20th Century Optiscope Company proclaimed its own determination "to live up to the rules and regulations in every way." It accused the Yale Amusement Company—its principal competitor in Kansas City—of price cutting and asked the manufacturers to make an example of it by stopping its supply of films.[56] A. D. Plintom of the Yale Amusement Company insisted on his own integrity and called the "Twentieth Century people . . . very unscrupulous in their methods."[57] William Swanson, who was on the FSA executive

board, complained that "here in Chicago the kikes have organized among themselves" to the detriment of the business. He characterized three or four renters— whom he was responsible for organizing into a local association—as vultures, blood suckers, thieves, and price cutters.[58] Swanson was clearly jealous of Laemmle's success. The Standard Film Exchange informed Dyer that Swanson's animosity toward them had existed before the formation of the association and invited "close scrutiny of our business methods at any and all times."[59] The Yale Amusement Company accused Swanson of illegally opening a branch office in Kansas City and severe price cutting as he attempted to win a toehold in his new territory.[60] Other exchanges also opened unauthorized branch offices.

By June 1908 the situation had become serious enough for Thomas Edison to intervene publicly. Claiming that he was "for the first time taking a personal interest in the strictly commercial side of the business," he put the full weight of his authority behind the venture. In an interview with Variety , he announced,

I am aware of some of the restlessness and minor dissatisfactions among the dealers. This is a natural condition. No big movement was ever perfected without experiment. That's what we are doing now—experimenting. And I may say we are experimenting to some purpose.

What we want to see is a system of business in which everybody is satisfied, everybody making money and getting a full return upon his investment of brains, money and labor. This is the goal toward which we are working. If the progress at times seems slow, it is none the less sure, and our arrival there is a matter of a very short time. This is a great organization. It cannot be administered haphazard[ly]. Each movement must be carefully considered.[61]

The Association of Edison Licensees was likened to an invention that would be improved through constant tinkering and experimentation. Now that the Wizard himself had intervened, the problems would be solved to everyone's satisfaction.

Edison was already enjoying financial benefits from the new organization. Beyond the Edison Company's impressive film-related profits of $410,959 for the 1908 business year, the inventor was receiving additional monies from his licensing arrangements. Lubin sent Edison $3,200 in royalties for the period between February 1st and June 20th.[62] Essanay paid approximately $6,000 during the first year, Pathé $17,000 or $18,000.[63] Edison's total royalty for the first year approximated $60,000.[64] Yet Edison and association members realized that the imperfect nature of the "trust" prevented the organization from operating effectively. Many considered an alliance of Biograph and Edison interests as the only way to achieve the associations' original goals.

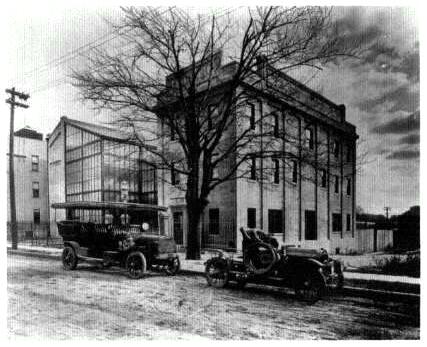

The new Bronx studio.

The Edison Manufacturing Company Opens Its Bronx Studio

Gilmore's belated decision to increase the rate of film production in response to the demands of the nickelodeon era coincided with the hiring of James Searle Dawley on May 13, 1907.[65] A playwright, Dawley had been working for the Brooklyn-based Spooner Stock Company as its stage manager. His adaptation of Ouïda's Under Two Flags and his musical comedy Aladdin and His Magic Lamp were performed by the Spooner Company during the theatrical season.[66] Another one of his plays, On Shanon's Shore , had been copyrighted by the Spooners.[67] Dawley was in charge of renting films that were shown between acts of the stock company's plays, a job that took him to Waters' Kinetograph Company, where he eventually met Porter. As the theatrical season came to a close, Dawley was looking for employment. After an interview, the studio manager offered him a job at $40 a week.[68] Dawley joined Porter's staff but did not give up the theater: over the next year and a half, he was to complete at least four plays.[69]

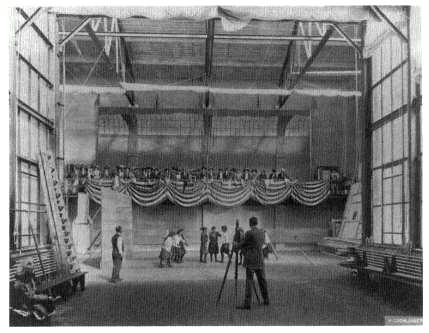

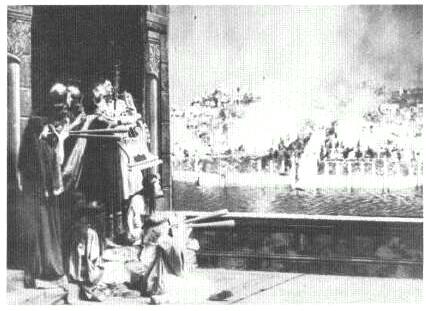

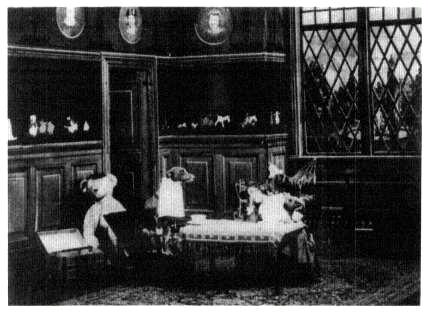

Filming A Country Girl's Seminary Life and Experiences inside Edison's new studio

in March 1908. Next page, a frame from the film.

Two weeks after Dawley joined the Edison staff, Wallace McCutcheon left the Kinetograph Department. The reasons for McCutcheon's departure are unknown, but Porter's salary had been increased from $40 to $50 in March while his remained unchanged. By October 1907 McCutcheon was back working for Biograph.[70] Although Dawley arrived during the making of Cohen's Fire Sale , he remembered Porter's next film, The Nine Lives of a Cat (July 1907), as "my first picture." It was also the last subject to be made before the filmmakers moved into their new studio.

Edison executives had recognized that they needed a new studio soon after fiction narrative films became the company's dominant type of film production. Joseph McCoy, who found a site for the new structure, recalled:

In 1904-5 the Edison Company decided to build a moving picture studio in New York and it was up to me to select a suitable location. I looked at all the vacant places that real estate dealers had listed in Manhattan, but their prices were all too high. I then went over to the Bronx and selected about twelve locations. Mr. Dennison was Secretary of the Company at the time and a photographer. He took photographs of the locations I selected to show to Mr. Gilmore. Moore, Porter and Pelzer visited all the

locations and selected the ground for the studio at 198th Street and Oliver Place, 100 × 100, property owned by Frederick Fox and Company, real estate dealers.

I called to see Fox about buying the property. Fox said he would sell the property for $13,000. I wanted a ten day option on the property at that price. He assured me that the price would be no higher. A couple of days later he telephoned me that his price on the property would be $15,000. I took the matter of the increased price up with Mr. Gilmore. Gilmore, Moore, Pelzer and Ed. Porter looked the location over carefully. As the price of $15,000 was lower than the other locations, Mr. Gilmore said "Take it at the price of $15,000."[71]

This 100' × 100' plot of land on the north side of Oliver Place and the east side of Decatur Avenue near Bronx Park was purchased for $15,000 on June 20, 1905, from the City of New York.[72]

The studio was to be built using reinforced concrete and Edison Portland Cement. Agreements to complete the studio by the spring of 1906 were signed with several contractors just before Christmas 1905. Delays followed. Serious work did not begin on the studio until summer, at which time the studio's completion was announced for the fall at an anticipated cost of $50,000.[73] (The actual cost was $39,557—not including land.)[74] Construction continued over the next year, however, taking much of Moore and Porter's time. As Dawley recalled in his hesitant, scrawled memoirs:

I had the pleasure of watching [the big studio in the Bronx] being built and help [put into working [order]. What a huge place it seem[ed] to Porter and I after working h our former place, a[n] old abandoned photographic studio on the top floor of the building with a sky light roof. Every time we started to take a picture we would hay to run out on the roof next door and see if the sun would pass over a cloud . . . our 21st street studio was about the size of a large office room.

Our Bronx studio seemed like a whole floor in comparison but before 2 years were out, it seemed to be to[o] small.[75]

Porter and his colleagues moved into their new headquarters on July 11, 1907, although much of the work was unfinished.[76] Heating and ventilation were not completed until October 15th. A roof had to be redone by mid De cember. The studio was near enough to final completion for publicity photo graphs to be taken on March 14, 1908, during the making of A Country Girl's Seminary Life and Experiences .[77] "The Edison studio is said to be one of the finest and largest of its kind in the world," reported the Dramatic Mirror . "The building itself is 60 by 100 feet, built of concrete, iron and glass. The scenic end of the studio, corresponding to the stage in a theatre, except that it is not raised is 60 by 60 feet and 40 feet high. Here the scenes for film productions that cannot be made with natural outdoor backgrounds are painted and set."[78] With work continuing until June or July, the fitting out of the new studio was largely Porter's responsibility. This included custom designs for everything from lighting equipment to a mechanized developing setup for negatives (which he personally operated). The studio emulated Edison's laboratory, with all likely materials and gadgets close at hand (see document no. 23).

DOCUMENT NO. 23 |

EDISON CO.'S NEW STUDIO. |

On a hillside near Webster avenue, the Bronx, New York, the Edison Manufacturing Company has erected a unique building, entirely of one piece, like a rockhewn temple. The material is concrete, with a roof of glass over the larger portion of the building. This odd looking structure attracts the attention of every passerby, while comments upon its probable use are varied and often ludicrous. Some are sure it is an electric power house, although the glass roof is puzzling; others think it is a dynamite factory built to avoid danger from explosion and fire. |

Construction on the building commenced in the summer of 1906; its concrete walls, floors, roofs, ceilings and window casings, all molded in the soft mixture which was used thousands of years ago by the ancient builders, were put up before winter set in. An inspection of this method of house building will convince any one that Mr. Edison is right in using concrete for a photographic studio. Not to mention economy in cost, the |

(Text box continued on next page)

hardness is that of rock itself, and therefore neither dampness, frost, nor gnawing rodents can affect it. Dust is minimized, and the floors and walks can be cleaned, washed or swept like a stone house. Again it is hermetically air proof and cold proof, while in the summer the heat penetrates slowly. |

All these considerations are of great value to photographers and the building of a moving picture. The building extends for 100 feet along Decatur avenue; it is 60 feet wide and 35 feet high—an imposing object seen from Webster avenue. |

This studio is in two parts, distinct, but standing on a common basement story. On the south side stands a plain oblong office building, three stories high, containing offices, dressing rooms, chemical laboratories, darkrooms, tankrooms and drying halls, with other necessary compartments. This faces a glass court. These two parts are connected by a sort of open hall, or atrium, directly open to the stage in the studio. |

The main entrance to the offices on the avenue side opens into an entrance hall or reception room for visitors, neatly furnished. On the left is the door of the loading and chemical washrooms, which can in a moment be turned into a darkroom by simply switching off the light and shutting the door. Here a faint red light burns, and the photographer can "load" the eight inch circular boxes holding the blank films. Many other details of the work are done here also. On the right of the reception room a door leads into the main office. It is a neatly kept room, with the usual desks and office furniture, and on one side is a library shelf of books, including history, romance, adventure, travel, fairy tales—books from which particular information is gathered for constructing plots for the pictures. |

Passing through the offices one comes out into the main hall or atrium before mentioned, whence a full view of the stage is obtained, of which more anon. Opposite the doors of the dressing rooms are seen, and these are four in number. Each dressing room is fitted up as in a theater, with makeup stands and tables, long wall mirrors, wash basins and even shower baths, while the windows are given plenty of light—more, probably, than many an actual theater room can boast. Every convenience and necessity is provided, except, indeed, easy chairs, for there is no lounging whatever in the Edison studio. A busier place would be hard to find. |

Down under the main floor is a long, roomy place of great interest— the property room. Yes, there is even the property man here, for the numerous costumes, paraphernalia and necessaries of the work are legion and must be carefully taken stock of. Mr. W. J. Gilroy is property man, and has many interesting features to show one down in the 60 foot long property room. Among other articles are 18 Springfield rifles and a small |

(Text box continued on next page)

armory of other weapons, toys, Roman togas, fairy costumes and lay figures, eagles, and so on. Although not yet a year old, the property room is already filling up. |

Upstairs, on the second floor, are certain mysterious rooms, where uninitiated persons are not admitted, although it is to be guessed that they are for experimental work and secrets of the trade. On the third floor, however, are some highly fascinating rooms, the developing and drying chambers, photographic darkroom and chemical laboratories. |

E. S. Porter, chief photographer and superintendent, is eminently fitted for the responsible position he holds. His ingenuity is constantly exercised; inventiveness and practical method, so necessary to the building of motion pictures, are at his finger ends. |

The scenes painted under Mr. Stevens' direction by the scenic artists, are in distemper—that is, they use only blacks, browns and whites, with the varying shades of these, as photographs do not take color as color, but only suggest it. Houses or block scenery are built up and the stands and wings constructed as in a theatre, only with much more attention to details and naturalness. For the camera, unlike the eye, can not be easily deceived. "Staginess" is avoided and realism is in every case given place over "effect." Scenes indoors can be taken at any time, now that the new and wonderful artificial daylight has been introduced at the studio. |

Much of the apparatus for controlling this light is the device of Mr. Porter himself, and the strength of the violet rays capable of being thrown from any part of the stage on any other part is almost beyond belief. Equal to a thousand of the ordinary arc lamps, the light concentrated on the stage by the reflectors is in photographic effect calculated at the following intensity: Taking the arc street light at its usual power of one thousand standard candles, the studio light equals one million candle power. Such a light in violet rays, is not glaring, but is like daylight diffused. |

The electrical equipment of the whole building is perfect and interchangeable, and especially so these mysterious stage lights. An ordinary theater switch box, with spider boxes and the usual maze of connections, is used. Electric motors of different sizes come handy for mechanical effects, and so there can be produced any sort of scene whatever, even a water scene. |

A water scene? Certainly; and the mystery is explained when we examine the floor of the stage. This floor, 55 × 35 feet, is built in square sections, which can be lifted away, one by one. Beneath is discovered a great tank, the full size of the stage and 8 feet deep. The floor and beams |

(Text box continued on next page)

are so arranged as to render the formation of a pond, a fountain or lake, or even the seashore, easy according to the number of sections of floor taken up. |

A film several hundred feet long would hardly go into a photographer's developing tray, except in Brobdingnag, the giant's country; so special apparatus is used in development. The finest equipment probably in the world is here at the Edison studio. Up on the third floor is a mysterious room, which at first glance looks like some new kind of Turkish bath, there being six porcelain tubs ranged down its length. These are as large as bathtubs, much like them in appearance, but have apparatus around which would disconcert anything but a chameleon. Underneath each is a gas jet series for heating, and at each end are axles, cranks and motors. The latter are compact little devices which are used to turn the axles aforesaid. Now the other side of the room contains several huge drums, hollow and open ended, like cylinders. Mr. Porter who himself conducts the important process of developing, places one of the cylinder drums on the axles of the first tank. This contains the developer and the bottom of the drum dips into the fluid. Then a negative is unwound, all light having been excluded by double curtains at the window and a red light turned on along the falls. The several hundred feet of film is wound carefully on the drum, which is kept in motion until the pictures on the negative begin to "come up." The red light burns magically, lighting dimly the great revolving drum, like a hall of necromancy. The light comes from curious conical devices. |

After development the drum is lifted into a tank of water, warmer than blood heat, and from there at once lifted over to number three tank, where the hypo clears the pictures. While the first drum is on its way down the room from tank to tank a second and third are started after it, each bearing many hundreds of tiny pictures. The series of tanks contain: No. 1, developer; No. 2, warm water; No. 3, hypo; Nos. 4 and 5, water— the bathing is to wash clean the films of hypo—and No. 6, glycerin and water, to render the films pliable in handling. |

Behind the developing room is a large chemical dark room and laboratory, and outside these rooms is the drying hall, where films are reeled off on great seven-foot high wooden drums, which each holds a thousand feet of film. Here there must be no dust, as that would settle on the pictures and look like pieces of coal in magnifying the scenes on a screen. So the advantage of stone floors, walls and ceilings becomes manifest. Even the too high speeding of the rollers is avoided to prevent currents of dust carrying air. |

The drying is followed by careful inspection and brushing off, and then |

(Text box continued on next page)

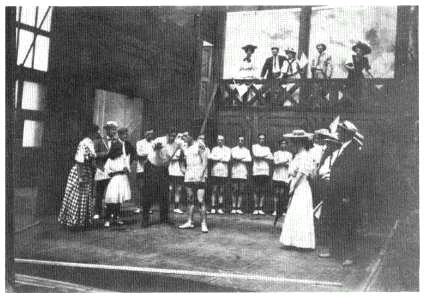

Stage Struck and A Race for Millions.

the films are reeled into their boxes again, ready for shipment to Lewellyn park, where they are developed into positives and prepared for market. |

SOURCE:Film Index , November 28, 1908, p. 4. |

One of Dawley's responsibilities in the new studio was to keep payroll records for actors. These records, as well as some of Dawley's later statements, have led some historians to credit Dawley as author and director of many Edison films of which Porter was in fact producer, (co)scriptwriter, cameraman, editor, and lab technician. While the nature of their collaboration makes attribution of sole authorship inappropriate, Porter retained the dominant role. Dawley was "stage manager" or "stage director" and responsible for blocking and acting. Dawley not only worked under Porter but had little involvement with filmic elements such as camerawork and editing. Porter's former collaboration with McCutcheon provides a comparable model for the relationship between these two men, with one essential difference. In the beginning Dawley was learning about motion pictures and deferred to his studio chief and cameraman more readily than his predecessor. Dawley acknowledged that Porter knew what he wanted, and it was the new employee's job to help him get it. Films such as Rescued from an Eagle's Nest thus continued Porter's previous work in both subject matter and treatment. The two only worked together for a year, after which Dawley was given his own production unit to head. During Dawley's first year, it seems more appropriate to attribute the films that Porter supervised, shot, and edited primarily to the veteran rather than the novice. If this was not the case, Dawley rather than Porter would have taken the blame for the Kinetograph Department's subsequent difficulties.

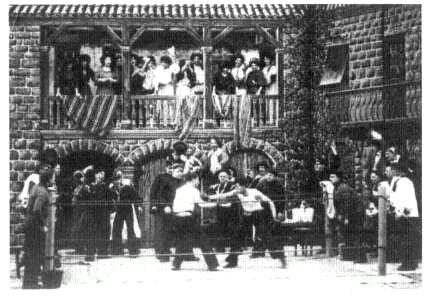

Stage Struck (July-August 1907) was the first film to be made in the new Edison studio. It starred Herbert Prior as an impoverished thespian who helps three sisters escape the farm for a career on the vaudeville stage. The exteriors

for Stage Struck were shot around New York City—at Coney Island and probably in the Bronx. Two scenes utilized the expanded possibilities offered by the new studio. One set created a concert garden where the thespian and three sisters performed on a substantial stage while the girls' parents sat at a table in the foreground viewing the performance. For another set, a "Human Roulette Wheel" was constructed and used in a chase sequence as the farmer tried to capture his wayward daughters. The wheel was not essential to the story, but Porter could not have filmed this indoor amusement either at Coney Island, where the lighting was inadequate, or in the old studio, which was too small. Porter next used the studio to create a western locale for A Race for Millions (August—September 1907). A car was driven on stage, again something that had been impossible at the old Twenty-first Street rooftop. The studio became a plaything as Porter and his associates explored its many fascinating possibilities.

Once in the new studio, the Kinetograph Department responded to the demand for more films. For the remainder of Porter's tenure, the rate of production increased. In August 1907 the studio staff averaged two films per month; by February and March 1908 they were producing at twice that rate and releasing a new film each week. In some cases, these films were very short. Playmates (February 1908) was only 360 feet long. Within a few months, however, the production staff produced close to a reel of film per week-often of more than one subject. The whole approach to filmmaking shifted. Until February, distribution was determined by the production schedule. When a film was completed, it was readied for release and copies were then sold to the various exchanges. With the release system instituted by the licensees, this arrangement was reversed. The rate of production was dictated not by Porter's needs but by the distribution system.

Dawley's records show that the number of days in active production (for which actors were hired) increased substantially over this period, while the average number of shooting days per film decreased only slightly. Less time was devoted to preproduction, and work on each film became more concentrated. The studio rarely hired players who had other acting commitments during a production. In June 1907 the Edison payroll ledger listed four men as making negative film subjects: Porter at $50 a week, J. Searle Dawley at $40, and William Martinetti and George Stevens at $20 a week each. They were assisted by staff members in other payroll categories, like William Gilroy, who received $15 a week. When the group moved into the new studio, Henry Cronjager was hired at $20 a week as Porter's assistant cameraman.[79] In September Martinetti left and was replaced by the set designer Richard Murphy.[80] With staff size and rate of production moving upward, Porter's salary was raised to $65 a week.

By late 1907 the Kinetograph Department was casting a group of actors with increasing regularity. Receiving $5 a day each, they derived a significant portion of their income from the studio. Edward Boulden appeared in eight films be-

tween September 1907 (Jack the Kisser ) and March 1908 (The Cowboy and the Schoolmarm ), and returned subsequently after a few months' absence. A Mr. Sullivan performed in The Trainer's Daughter (November 1907) and ten other films over the next six months. William Sorelle, who also made his first documented Edison appearance in The Trainer's Daughter , acted in more than twenty films over the next year. John (Jack) Frazer appeared in Stage Struck (July 1907) and then joined the Edison staff in September at $18 a week. His baby daughter Jinnie appeared in The Rivals (August 1907); in her next performance, she was stolen by a mechanical eagle in Rescued from an Eagle's Nest (January 1908). Jinnie Frazer continued to appear in Edison films whenever an infant was needed.

Some of the actors had worked for Porter as early as 1903. Boulden had been the shoe clerk in The Gay Shoe Clerk . Phineas Nairs, who played the detective in The Kleptomaniac (1905), was steadily employed at the Bronx studio after Fireside Reminiscences (January 1908). John Wade, who had been tarred and feathered in The "White Caps " (1905), appeared in Stage Struck and five other Edison films. Gordon Sackville, who had acted for Porter as early as 1904, appeared in Tale the Autumn Leaves Told (March 1908) and Nero and the Burning of Rome (April 1908). He later appeared in Porter's first production for Rex, The Heroine of '76 .[81] Other actors had worked with Dawley in the Spooner Stock Company; among these were Harold Kennedy, Augustus Phillips, and Jessie McAllister. Laura Sawyer, who would become one of Edison's leading players, made her first appearance in Fireside Reminiscences .

A number of actors maintained a loose association with the Edison Company. Kate Bruce appeared in five films over ten months, Miss Francis Sullivan in four, and a Mr. Elaxander in five. Others were associated with the company for two or three films and then moved on, among them D. W. (Lawrence) Griffith. Griffith had been an extra in at least two Biograph films in late 1907 before winning a starring role in Porter's Rescued from an Eagle's Nest . He then worked as an extra at Biograph in mid January before returning to Edison in a similar position for Cupid's Pranks (February 1908).[82] As his connection with Biograph developed and the "film war" heated up, the actor severed his ties with the Edison Company. Herbert Prior appeared in Stage Struck and Nellie, the Pretty Typewriter (February 1908), then moved on to Biograph. He eventually returned to Edison in late 1909 as a full-time stock company actor.[83]

The development of an informal stock company grew naturally out of the increased rate of production and enabled Porter and his colleagues to work with actors who were more or less familiar with Edison procedures and whose abilities were known in advance. Films were no longer treated as discrete, individual productions: there was little time for casting calls. This was only one aspect of the Edison Manufacturing Company's hesitant move toward a studio system. Under Porter, there were some department heads: a prop man, an art director,

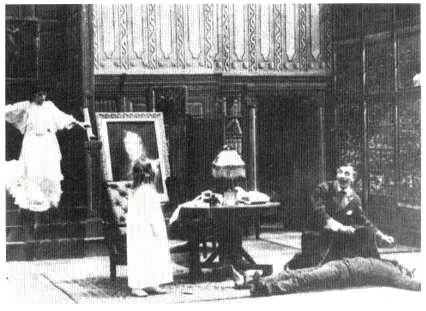

The Devil.

and a stage manager in charge of the actors. Yet Porter also retained complete control over photography, editing, and developing—over all the filmic elements. A division of labor was only partially and unevenly instituted. Many of the gains in the rate of production were accomplished not by increased efficiency but by increased personnel. Edison's rising production level, moreover, was only part of a larger phenomenon occurring throughout the industry. This general increase undermined the representational system that had been established in the period before the nickelodeon.

Narrative Clarity: 1907-1909

The explosion in film production meant that reliance on the spectator's prior familiarity with a story was becoming rapidly outmoded. A textbook demonstration was offered by Arthur Honig, who analyzed the viewer's reaction to Porter's The Devil (September 1908). This critic had already witnessed Henry Savage's play of that title when he saw Porter's adaptation. He not only used the play as an aid to following the film's narrative, but imagined the spoken lines and judged the acting and sets in relation to the play. For a modest nickel, Honig happily recalled the Savage production. While pleased with the film, this writer was also accompanied by "an intelligent friend" who had never seen the play. The friend started asking Honig questions about the story line, forcing him into

the role of personal narrator. Without the necessary frame of reference, the friend's enjoyment of the film was spoiled.[84] Like Honig, the Dramatic Mirror felt that "the Edison players did remarkably well, although to appreciate the pictures one must have seen the original play or read the story."[85] The average nickelodeon viewer did not have this special knowledge, however, and was at a loss to understand the narrative.

While the moving picture world increasingly avoided relying on an audience's prior knowledge of the story, Porter continued to depend on it. Such reliance was fatal, however, in two respects. First, since only a limited number of stories had wide circulation in American popular culture, it limited available narratives unacceptably. There were just not enough stories to go around. Second, the craze or hit on which a story was based often had a more limited audience than the film that emulated it. Narrow, specialized audiences for such films were undesirable and created problems for renters and exhibitors who served a mass audience. Porter and his contemporaries continued to use simple stories and variations on a single gag as the basis for their film narratives, but these were also incapable of providing an overall solution to the problem. As a group, these films were too lacking in diversity and too limited in the kinds of subject matter they could portray.

As the rate of production increased in 1907-8, the only way to achieve product diversity was through the use of more complex, unfamiliar narratives. As this happened, audiences often found it difficult to follow what they saw on the screen. Variety remarked of one film:

This reel offends against the most important of the elements of motion photography—following it involves a decided mental strain. Moving picture subjects, we take it, should be selected first of all for their directness, simplicity and ease of adequate exposition. As little as possible should be left out to the unaided imagination of the spectator. The story, the whole story and nothing but the story should appear on the illuminated sheet. In this subject an effort has been made to tell a complicated and intricate allegory. . . . When it is all over the spectator asks himself what it is all about. That's enough to mark the best picture, mechanically, ever made a failure.[86]

In a fictitious exchange between two moviegoers, one declares, "I guess they have exhausted all of the old subjects and have nothing else to show us than pictures we cannot understand." Her friend agrees, "Yes, they are at the end of their rope."[87] These complaints were common. People "do not want to sit in a dark room, yawning and asking their neighbors, 'What do the pictures mean?'" Moving Picture World observed.[88] The problem of narrative clarity could be solved either (1) by producing self-sufficient work that could be understood without assistance from the exhibitor or the audience's special knowledge of the material, or (2) by facilitating audience understanding through a lecture or

behind-the-screen effects and dialogue. Porter's work was aligned with this second alternative.

The Lecture

The lecture, always an important strategy in the exhibitor's repertoire, was the focus of renewed interest by early 1908. In January Billboard reported: "Many moving picture houses are adding a lecturer to their theatre. The explanation of the pictures by an efficient talker adds much to their realism."[89] W. Stephen Bush, a former traveling exhibitor and a frequent contributor to Moving Picture World , considered the lecture "a creative aid to the moving picture entertainment." Bush, who often lectured at church functions, approached cinema as a traditionalist who wanted to instruct as well as entertain. He condemned the uneducated exhibitor who showed a Shakespearean play on film without a lecture and "bewildered his patrons, who might have been thrilled and delighted with a proper presentation of the work."[90] Bush prepared and offered to sell special lectures, with suggestions as to music and effects, for every feature turned out by the Edison licensees.[91] He was probably the anonymous reviewer who felt that Porter's The Devil "is a fine production and if given with a lecture yields little to the real play."[92] Likewise, Colonial Virginia (made in May 1907 and eventually released by Edison in November 1908) needed "to be presented with a lecture for the spectators to fully understand and appreciate the scenes that are presented."[93]

Bush argued that a nickelodeon's addition of a skilled lecturer would more than offset the additional salary costs by increasing patronage and turnover. "Why do so many people remain in the moving picture theater and look at the same picture two and even three times?" he asked. "Simply because they do not understand it the first time; and this is by no means in every case a reflection on their intelligence. Once it is made plain to them, their curiosity is gratified, they are pleased and go."[94] In an article entitled "The Value of a Lecture," Van C. Lee claimed surprise that "the managers are just awakening to the fact that a lecture adds much to the realism of a moving picture." Like Bush he asked his readers, "Of what interest is a picture at all if it is not understood?"[95]

Bush's and Lee's viewpoints were substantiated by considerable evidence. James H. Flattery, a humorist and elocutionist who had been in the Ed Harrigan Irish Comedian Company, lectured at the Novelty Theater on Third Avenue in New York City with great success, large crowds packing the theater each night.[96] The Casino Company, which owned a half dozen theaters, tried out a lecturer in its three Detroit houses and then added "talkers" in its three Toledo, Ohio, venues.[97] The lecture, however, encountered serious obstacles. A film fan in Augusta, Georgia, tried to convince local managers to add a lecture and found that they were reluctant to increase their expenses.[98] Some exhibitors lacked

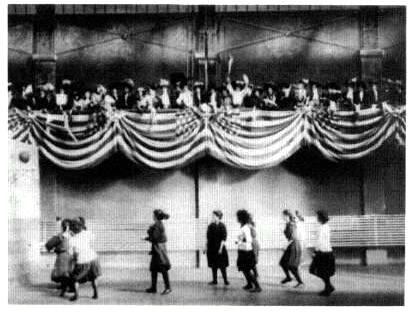

Left: Spook Minstrels. Right: Vesta Victoria sings "Waiting at the Church."

access to plot synopses and often did not entirely follow the stories themselves. Furthermore, talented lecturers were difficult to find. General reliance on lectures was unlikely, given the rapid turnover of subject matter, the exhibitor's narrow profit margin, and the substantial number of films that were intelligible without such aid. In seeking to apply traditional strategies of screen presentation to this new form of mass exhibition, Bush and Lee failed to acknowledge the many obstacles that prohibited its broad application.

"Talking Pictures"

The technique of giving live dialogue to screen characters has a long history. In the mid 1890s Alexander Black changed his voice when he endowed the characters in his picture plays with speech. Starting as early as 1898, Lyman Howe's success was "largely due to his well trained assistants who render the dialogue behind the screen."[99] Having become familiar with this procedure at the Eden Musee while projecting The Opera of Martha , Porter photographed a minstrel performance, Spook Minstrels , late in 1904. Spook Minstrels opened on a vaudeville bill at Harry Davis's Grand Opera House in Pittsburgh on January 9, 1905.[100] A month later, it reached New York City's Circle Theater, where it was reviewed:

A distinct novelty on the bill was the first appearance of Havez and Youngson's Spook Minstrels , in which moving pictures are used in a novel way. The pictures show a minstrel company going through a performance, and as the various numbers are presented the songs, jokes and dances are given by men who stand behind the screen and follow the motions of the men in the picture very accurately. The act is original and novel and was highly appreciated. The performers who do the work and who later on appeared before the curtain and sang some additional songs are G. Dey O'Hara, Charles Bates, Leon Parmet, Parvin Witte and Charles Smith.[101]

Songs included "Will You Love Me in December as You Do in May," "In Dear Old Georgia," and "My Octoroon Lady."[102] The act continued to appear at such vaudeville houses as Keith's Union Square Theater, where "the singing of the quartette won unbounded acclaim."[103] The film remained popular for many years. In the fall of 1908, it was being shown as a special at the Bijou Theater in Providence, Rhode Island, along with a regular motion picture program.[104]

The same principle was used when Porter filmed a version of Waiting at the Church for the Novelty Song Film Company in January 1907. Vesta Victoria was brought to Edison's Twenty-first Street studio and photographed as she sang "Waiting at the Church" in a wedding gown that was part of her smash vaudeville act. Afterwards, in another costume, she sang "Poor John," a song that was to be that season's hit. At least some of the prints were tinted. According to one announcement, "In 'Poor John' she wears for a costume a bright red satin dress with trimmings of green satin ruffles, a short box coat of imitation ermine with a small cap and tiny muff of the same."[105] In the company's theaters a singer stood behind the screen and sang synchronously with the picture, leaving the audience with the impression of having witnessed an amazingly lifelike performance from Vesta Victoria.

After playing the films in their theaters for several months, the Novelty Song Film Company sold copies to fellow exhibitors:

5 & 10¢ THEATRES—NEW, NOVEL—A TRADE BRINGER.

We have a proposition in films that we believe will interest you. We are ourselves operating several five and ten cent theatres, and found that there was a great demand for novelties, particularly films to be used in connection with the singer. We posed Vesta Victoria (probably the highest salaried and best known performer in America to-day), singing her two most successful songs, "Waiting at the Church" and her latest hit "Poor John." This film is about 400 feet long and is unusually clear and lifelike.[106]

Even prior to this announcement, purchases were made by Waters' Kinetograph Company.[107] Keith's organization was headlining Vesta Victoria in its vaudeville theaters and wanted the films shown in its film houses too. When they reached Keith's Nickel Theater in Manchester, New Hampshire, promotional blurbs claimed that the films had been taken at its Boston vaudeville house the previous week. While the singer behind the screen usually imitated Vesta Victoria as closely as possible, in some instances the comedic songs were further burlesqued. At Keith's Nickel Theater in Lewiston, Maine, "Poor John" and "Waiting at the Church" were sung alternately by Mr. and Mrs. Harriman Frost.[108] A male voice in combination with Victoria's diminutive figure simply added to the song's hilarity.

Thomas Edison's expressed wish to preserve operatic performance from the passage of time with a combination phonograph/kinetoscope was implemented

A company of performers who delivered dialogue

behind the screen for Uncle Tom's Cabin.

in a more practical and profit-oriented form. Audiences could be given the illusion of seeing Vesta Victoria, while management only had to pay an unknown performer to sing. Likewise a quartet could give the illusion of being a large troupe. In both cases, cost efficiency plus the novelty of the illusion was the secret of success.

Although Lyman Howe used sound imitators behind the screen in the 1890s, this only became a heavily promoted part of his exhibitions in August 1907, when his "Moving Pictures That Talk" played at Ford's Opera House in Baltimore for four weeks. Trained assistants "yelled orders when the marines attacked the land force, made noises like the popping of guns and the booming of cannon, and helped the figures on the canvas to carry out the proper amount of conversations at suitable times."[109] The exhibitions attracted immense crowds despite adult admission fees of between 25¢ and 50¢. Lubin, who found it expedient to close and refurbish his Baltimore film theater during Howe's run, soon placed actors behind the screen in his Philadelphia theaters. It was reported that Lubin's manager "has a well-known dramatist that writes plays around the pictures and then as they are thrown on the screen a company of actors play the

parts, speaking the lines to suit the action of the pictures. This is one of the most novel ideas ever sprung in this section and is making an enormous hit."[110]

By spring "talking pictures" had become a hit in New York, playing at Charles E. Blaney's Third Avenue Theater. Each Saturday Blaney's "dramatist" selected films from the manufacturer's latest productions and wrote the lines.[111] That May talking pictures were presented on Marcus Loew's People's Vaudeville Circuit "using the best dramatic talent available."[112] A large studio was set up in Loew's offices on University Place. Out of this may have come the Humanovo Producing Company, owned by Adolph Zukor and Marcus Loew and run by Will H. Stevens.[113] In a mid-1908 interview Stevens explained how he worked:

"I have to scratch through a great many films," said he, "to find those that will stand interpretation by speaking actors behind the curtains. I started with Adolph Zukor, who is the proprietor of the companies. We now have twenty-two Humanovo troupes on the road, each consisting of three people. Each company stays at a theatre one week and then moves on to the next stand, traveling like a vaudeville act and producing the same reel of pictures all the time. They travel in wheels, so that a theatre has a change of pictures and company each week. It requires about four days to rehearse a company. First I select a suitable picture; then I write a play for it, putting appropriate speeches in the mouths of the characters. I write off the parts, just as is done in regular plays, and rehearse the people carefully, introducing all possible effects and requiring the actors to move about the stage exactly as is represented in the films, so as to have the voices properly located to carry out the illusion.[114]

New York-based Len Spenser, a "pioneer" in supplying singers and operators to moving picture managers on a systematic basis, added a department in his agency that furnished trained, competent actors to do the talking behind the screen.[115] The Actologue Company, owned by the National Film Company of Detroit and the Lake Shore Film and Supply Company of Cleveland, had eight groups of actors on the road in July and fifteen in September.[116] The Toledo Film Exchange also had four companies for its "Talk-o-Photo" enterprise.[117] William Swanson had ten traveling through Texas and another eight in the Denver area during November.[118] O. T. Crawford's Ta-Mo-Pics (Ta lking Mov ing Pic tures) were playing in his theaters to immense audiences in November. Most actors, however, wanted to be more than a disembodied voice and saw these jobs as a stopgap. In late August many of the skilled performers left the Humanovo Company in preparation for the new theatrical season. Stevens was forced to hire amateurs and dramatic students.[119]

Many five-cent theaters improvised their own form of talking pictures, with inevitable variation in exhibition quality and effectiveness. "The possibilities of this sort of thing with trained actors and painstaking rehearsals are admitted," remarked the Dramatic Mirror , "but the manner in which the idea was carried out in the houses visited by THE MIRROR representative was grotesque and a

Most of College Chums was ideally suited for use of actors behind the screen

drawback to the pictures themselves. The odd effect of the voice of a 'barker' trying to represent several voices, some of them women and children, and in one case a dog, may be amusing as a freak exhibition, but can hardly add to the drawing power of the house."[120] Such makeshift efforts remained popular throughout the summer and fall.

Talking picture companies used an unusual number of Edison films. When the Humanovo played for two weeks at the Maryland Theater in Baltimore, three of their four films were made by Porter: College Chums (November 1907), A Suburbanite's Ingenious Alarm (December 1907), and Fireside Reminiscences (January 1908).[121] Half of the Actologue Company's films appear to have been Edison products, including College Chums, The Gentleman Burglar (May 1908), and Curious Mr. Curio (May 1908).[122] Porter's filmed version of Ferenc Molnár's The Devil was particularly suited for this mode of exhibition. As the Dramatic Mirror observed, "films of this kind may often serve as excellent vehicles for talking companies behind the curtain, and in this respect The Devil, as produced by the Edison people, offers unusual advantages."[123] In fact, the theatrical paper felt that the absence of such aids placed the film's accessibility in jeopardy. Talking pictures not only added "verisimilitude to the scene to an almost incredible degree" but made the story more intelligible.[124] "The dialogue helps the less intelligent to fully understand the plot, for no matter how skillfully worked out, there are always passages which require something more than mere

pantomime to fully explain the situation."[125] Porter's films, in particular, benefited from such treatment. The filmmaker did not so much abandon his reliance on the audience's prior knowledge as accommodate these pictures to the exhibitor's intervention. As with The Devil , unaccompanied screenings of Porter's films could often be appreciated by those who knew the necessary referents.

These "talking pictures" reached their peak by the end of 1908, when the practice, then widespread, began to lose some of its popularity in houses relying on untrained personnel.[126] In January, Stephen Bush, an earlier supporter of the practice, criticized it as "unnatural"—but only to endorse his favorite use of voice, the lecture.[127] Although his criticisms were immediately disputed by others, talking pictures gradually declined as a box-office attraction. Lyman Howe, however, kept impersonators behind the screen until his road shows closed in 1919.

Talking pictures were not a part of cinema's new mass communication system. They suffered from lack of standardization, and since the practice of adding behind-the-screen dialogue was never universally adopted, producers had to assume that actors would not be behind the canvas and seldom made films specifically for this purpose. As the new, more self-sufficient representational system developed, ancillary dialogue became less and less necessary. Moreover, the nickelodeons' customary daily change of program precluded sufficient time for rehearsal. Nor were many people up to performing twenty or more times a day. With specialty services, the additional expense of hiring and transporting actors had to be compensated for by a higher admission price. Although middle-class audiences could afford to pay for the increased enjoyment offered, the practice was never a realistic option for storefront theaters that charged a nickel and depended on working-class patrons.

Talking pictures were part of an emphasis on greater illusionism that, although common in the history of the screen, was particularly intense during the early nickelodeon era. Hale's Tours was first introduced in the spring of 1905 and became a fad by the following year. (Adolph Zukor's capitalization on talking pictures was not so coincidental, given that his initial involvement in cinema had been through Hale's Tours.) Pathé's coloring processes using stencils and the slightly later Smith/Urban Kinemacolor process, with its first public showings in late 1908, achieved startlingly naturalistic effects. Earlier uses of hand coloring, in contrast, had customarily heightened the fantastic elements of fairy-tale films like Jack and the Beanstalk and Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves . These attempts to expand the perceptual range to include sound, color, and bodily sensation further heightened the illusion of film as a transparent medium. The popular conception of film was shifting from cinema as a special kind of magic lantern to cinema as a special kind of theater.

Illusionism and theatricality were parallel currents in cinema that converged with "pictures that talk." As one enthusiast wrote, "The illusion of life which it is the mission of moving pictures to present to the best of its ability, must

always be incomplete, from the impossibility of adequately combining sound with sight, but there is no reason why the complete illusion should not be sought after, to a much greater degree than at present, by the means of stage effects."[128] The rise of talking pictures reveals much about the changes occurring within the institution of the screen during this period. It coincided with a new influx of theatrical directors like J. Searle Dawley, D. W. Griffith, and Sidney Olcott (who worked for the Kalem Company). It occurred at a time when cinema was taking over vaudeville and legitimate theaters and when a theatrical newspaper like the Dramatic Mirror had begun to review films. It was one of several converging elements in 1907-9 that defined film as a kind of theater—superior to the traditional stage in some respects (diversity of locale) though deficient in others (sound, color, and three-dimensional limitations). The move toward heightened realism in cinema, however, remained subservient to the narrative requirements of entertainment and the need for an efficient mode of exhibition that kept down the showman's expenses. Strategies to achieve a superrealism were abandoned or remained a specialty service because they either limited the filmmaker's freedom to tell a story or increased admission fees—or both. Intertitles were an extremely artificial representational strategy, but because they were an inexpensive and extremely effective way to clarify a narrative—whatever the exhibition circumstances—they quickly became standard industry practice.

Intertitles

By 1908 cinema was already perceived as "a language that is universal. No matter what may be the tongue spoken by the spectator, he can understand the pictures and enjoy them."[129] This "language" centered on the gesture of the actors, their rendering of the narrative, and other pro-filmic elements rather than the filmic "grammar" of Lev Kuleshov, Vsevolod Pudovkin, and later theoreticians. The filmmaker utilized this universal language to construct a narrative that could be understood by audiences with the support, where necessary, of a lecture, dialogue, or intertitles. The more successfully a story was rendered, the less this crutch was needed. Intertitles put this verbal accompaniment in the hands of the production company. Each subject became a complete work in itself, guaranteeing, in principle at least, the intelligibility of a company's films. This allowed for a uniformity of information that was central to an industry based on mass production and consumption.

As noted in chapters 8 and 9, Porter had incorporated intertitles into his films with some frequency between mid 1903 and the end of 1905, but then virtually abandoned the practice in 1906-7. Although the industry's only trade journal had urged film producers to use intertitles on a regular basis in September 1906, Porter ignored such requests. With demands for intertitles becoming more urgent, Porter returned to their use on a consistent basis with Fireside Reminiscences (January 1908). Intertitles were indicated in Moving Picture World syn-