Preferred Citation: Musser, Charles. Before the Nickelodeon: Edwin S. Porter and the Edison Manufacturing Company. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1991 1991. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft3q2nb2gw/

| Before the NickelodeonEdwin S. Porter and the Edison Manufacturing CompanyCharles MusserUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1991 The Regents of the University of California |

For Eileen Bowser

In Memory of Jay Leyda

Preferred Citation: Musser, Charles. Before the Nickelodeon: Edwin S. Porter and the Edison Manufacturing Company. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1991 1991. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft3q2nb2gw/

For Eileen Bowser

In Memory of Jay Leyda

Foreword

By its example, Charles Musser's elegantly argued study of Edwin S. Porter conveys two of the primary goals that the UCLA Film and Television Archive seeks to achieve in sponsoring scholarly publication.

In part we hope to underline the creative role played by film archives in making historical research possible and, often, in helping to set the field's scholarly agenda. The study of early cinema is reliant on the accessibility of films rescued and preserved by institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art, the Library of Congress, the International Museum of Photography, and the UCLA Film and Television Archive. The current worldwide revival of scholarly concern with early film can be traced back to the legendary symposium sponsored by the International Federation of Film Archives in Brighton, England, in 1978.

Our second goal in promoting scholarly publication is to celebrate and promote the renaissance of historical writing currently taking place in the field of film and television studies. After a long period of marginalization to the outer fringes of the discipline, serious historical research is now being rediscovered, redefined, and legitimated by a new generation of young scholars like Charles Musser.

In his writing Musser combines the traditionalist historian's respect for scholarly erudition with the contemporary historian's insistence on methodological self-consciousness, multidisciplinary discourse, and intellectual risktaking. Relying almost entirely on primary archival source materials to construct his arguments, Musser rejects timeworn and reductive explanations of historical causality such as auteurism and technological determinism. His dialectical approach to historical narrative freely crosses disciplinary boundaries to convey the complex interplay of aesthetics with a multifaceted social and industrial context.

In theory, the vast holdings of film and documents available through the nation's archives suggest the possibility of doing historical research that is truly definitive—the "last word" in the field. In practice, the current generation of intellectually expansive scholars are much too aware of the complexity of history to believe that interpretive closure is possible. In his commitment to both exhaustive archival research and audacious interpretation, Charles Musser exemplifies the creative potential in this contradiction.

ROBERT ROSEN

DIRECTOR

UCLA FILM AND TELEVISION ARCHIVE

Acknowledgments

An undertaking such as this can be accomplished only with the assistance of many people. I owe a particular debt to Jay Leyda, who taught my first film course. His advice and example over the intervening seventeen years have been a constant inspiration. My deepest regret is that he is not here to read this book, to which he contributed so generously. Eileen Bowser has sponsored the work of many students of early cinema. Her generosity and understanding have helped to make this project possible. In the process, she has become not only a friend and colleague but a quiet muse. To them, this book is dedicated.

This project began in the fall of 1976 in the context of an independent study with Jay Leyda. Unhappy with the frequently expressed assumption that cinema began with D. W. Griffith, Ismail Xavier and I went to the Library of Congress and looked at a group of early films from the Paper Print Collection. George Pratt taught me how to mine newspapers for information and then made his own research on Porter available to me. Pratt's rigorous, carefully documented articles on early cinema, as well as his thoughtful comments and continued enthusiasm, provided me with models of scholarly diligence. From Tony Keefer of the Connellsville Historical Society, I learned much about researching local history even as he kindly shared information about Porter's early life with me.

Robert Rosen of the UCLA Film and Television Archive and Angelo Humouda of the Cineteca D. W. Griffith in Genoa encouraged me to think of this study as a book from its early stages. The UCLA archive offered crucial assistance to this project at several junctures, and I am most pleased that it appears under its auspices. My own researches were supplemented by discussions and the sharing of information with associates interested in early cinema—

particularly with Noël Burch, Tom Gunning, André Gaudreault, David Levy, Paul Spehr, Pat Loughney, and Jon Gartenberg. Robert Sklar played an important role, providing thoughtful criticism and encouragement as I struggled to give this manuscript coherence and a form others would find useful. William K. Everson, William Simon, John Fell, Kristin Thompson, and Peter Dreyer provided me with thoughtful readings.

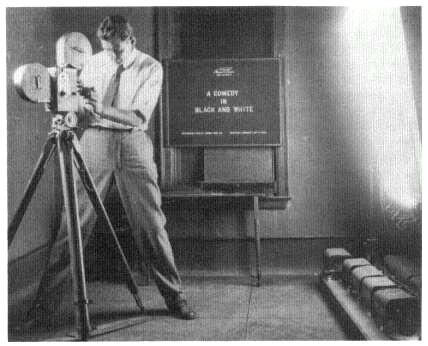

Portions of this manuscript have been previously published as articles. I am very grateful to the editors of Cinema Journal, Film and History, Framework , and Iris for the opportunity to reach audiences with some of these ideas before this study was completed.[1] Such opportunities to participate in the wide-ranging discussions revolving around early motion pictures and the practice of film historiography enabled me to refine my arguments and significantly improve the final manuscript. I am particularly grateful to the Society of Cinema Studies, which awarded the 1978 Student Award for Scholarly Writing to "The Early Cinema of Edwin Porter," the basis for chapter 6. This recognition facilitated the funding of Before the Nickelodeon , a film devoted to Porter's Edison career, and encouraged me to keep working on a project that has taken over ten years to complete.

Many people at various institutions went out of their way to assist this project. Pat Sheehan, Emily Sieger, Barbara Humphries, and Kathy Loughney at the Library of Congress; Mary Bowling, Ed Pershey, Reed Able, and Lea Burt at the Edison National Historic Site; John Kuiper and Chris Horak at the George Eastman House; Charles Silver, Ron Magliozzi, Jytte Jensen, and Mary Lea Bandy at the Museum of Modern Art; and David Francis, Roger Holman, and Elaine Burrows at the British Film Institute were all helpful on many separate occasions. Paula Jescavge at New York University's Bobst Library patiently filled many interlibrary loan requests. I am particularly indebted to the Department of Cinema Studies at New York University, where an earlier draft of this manuscript served as a dissertation.

Many other people deserve my thanks. Among them: Warren D. Leight, Rick King, Alexis Krasilovsky, Stephen Brier, John E. Allen, Reese V. Jenkins, Janet Staiger, John Fell, David Bordwell, Judith Mayne, Susan Kempler, John O'Connor, Martin Sopocy, Sam McElfresh, Standish Lawder, Miriam Hansen, Steven Higgins, Kemp Niver, Bebe Bergsten, Jack Miles, Joan Richardson, Anne Richardson, Don Ranvaud, Bob Summers, Porter Reilly, Charles Harpole, Herbert Reynolds, Roberta Pearson, Louise Spence, Richard and Diane Koszarski, Paul Killiam, Noël Carroll, Carol Nelson, Marilyn Schwartz, Pamela MacFarland, Blanche Sweet, and my family and friends. To Lynne Zeavin I and this book owe more than can readily be expressed. Finally, Ernest Callenbach, my patient and supportive editor, deserves particular thanks.

1

Introduction

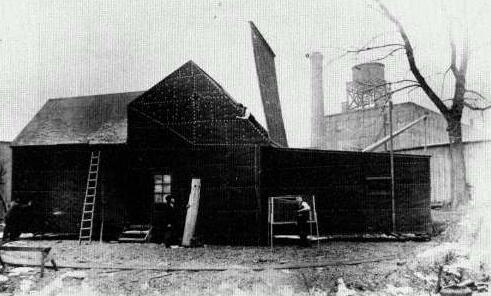

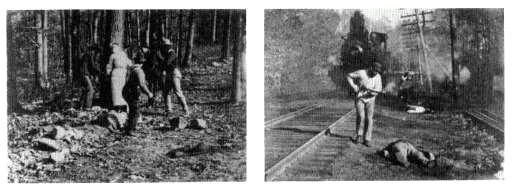

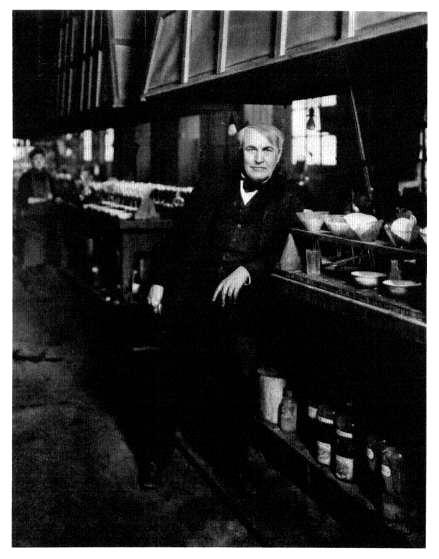

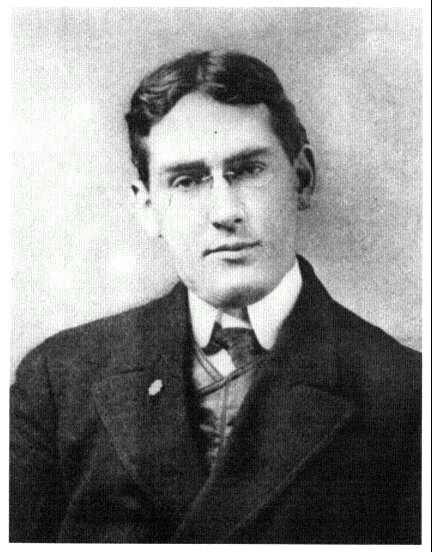

The first fifteen years of commercial motion pictures were extraordinary: film practices and the films not only differed fundamentally from today's counterparts but also underwent an unparalleled series of changes. During this formative period, Edwin S. Porter emerged as America's foremost filmmaker. Although many books have been written on D. W. Griffith, John Ford, and Orson Welles, not one has been published on the creator of The Great Train Robbery . This study is both a biography of the filmmaker Edwin S. Porter and an industrial history of the Edison Manufacturing Company from the beginning of commercial motion pictures through 1909—roughly until the formation of the Motion Picture Patents Company. This double focus is appropriate, for Porter and the Edison Company were associated in one form or another from the spring of 1896, when Porter entered the motion picture industry with a group that owned rights to "Edison's Vitascope," until 1909, when he left Edison's employ. In the interim, he worked for the Edison-licensed Eden Musee and then joined the Edison Manufacturing Company in late 1900. Within a few months he was a key member of the production team operating out of Edison's new motion picture studio. Within another two and a half years, he had become "head of negative production," a position he retained for the next six years.

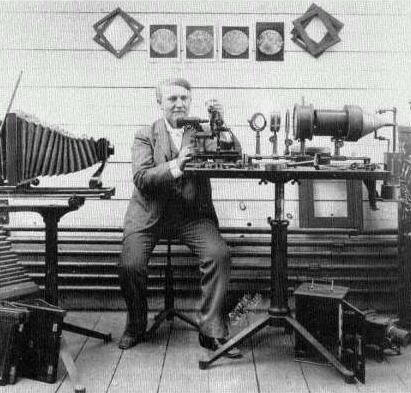

This dual focus proves efficacious in other respects. This undertaking does not dispute long-held assertions that Porter was the principal American filmmaker of the pre-Griffith era, even though I seek to cast that valorization in a new light. Correspondingly, Thomas Edison and his company were at the center of the industry's activities. In this regard, the commercial practices of the Edison Company were inextricably linked with Porter's creative role as film producer.

Each must be seen in light of the other. Porter's departure from Edison, moreover, was not arbitrary but occurred as his methods of film production and representation fell into disrepute and ascendant practices won the strong support of the Edison Company's new chief executive, Frank Dyer. This then is also a study of what has frequently been called "early cinema"—a loosely used term best applied to certain cinematic practices that became antiquated around 1907-8. If—as John Fell suggests—early cinema is pre-Griffith, then this study examines the pre-Griffith modes of representation and production in light of Porter/Edison activities.[1]

Edison's contributions to motion picture history, particularly during the stages of invention and initial commercialization, have been extensively examined by two important figures in film historiography: Terry Ramsaye and Gordon Hendricks.[2] Their assessments are diametrically opposed. Ramsaye's A Million and One Nights (1926) is a highly sympathetic account, read by Edison in manuscript and published with his endorsement. Ramsaye's widely read narrative supported—probably knowingly—the inventor's efforts to pre-date his motion picture inventions. These falsehoods were exposed in Hendricks's The Edison Motion Picture Myth (1961), which argued that America's greatest inventor was a sometimes grasping and unethical businessman. Angered by this realization, Hendricks developed a highly critical stance toward his subject. While staying close to "the facts," the historian interpreted them so unsympathetically that many of his conclusions must be questioned. Although this present text often relies on Hendricks's and Ramsaye's contributions to film historiography, it seeks to treat Edison and his company's activities in another light, from a perspective that might be called "critical sympathy."

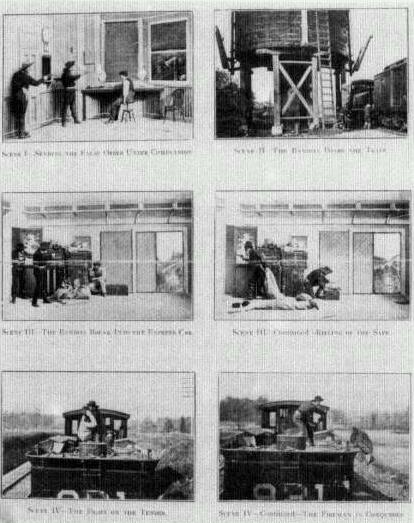

In grappling with Porter's contributions to cinema, most histories have concentrated on two of his productions—Life of an American Fireman and The Great Train Robbery —offering interpretations of these cinematic milestones rather than an understanding of the road they marked. Limited to a few films, their analyses fail to present a coherent interpretation of Porter's work. Perhaps this was inevitable, since these commentators wrote about Porter within the framework of a larger panorama covering many decades and thousands of extant films. The nature of their enterprise necessarily precluded the time, research, and thinking needed to offer a balanced overview of Porter's work. Moreover, their theoretical framework proved suspect. Writing at a time when it was necessary to emphasize that film was an art, Terry Ramsaye, Lewis Jacobs, and their successors conceived of Porter in romantic terms, as a "primitive artist" whose intuitive insights revolutionized the cinema. "Genius" became a methodological category that obfuscated the need for more critical insight.[3] Even recent overviews often continue to paraphrase Ramsaye's and Jacobs' assessments of Porter ("father of the story film" and "the inventor of editing") until they have become hopeless clichés.[4]

Although Porter has received his share of accolades, he also has his critics.

American historians have often viewed him as a lonely pioneer whose struggles to discover the new medium's untold possibilities were not entirely successful. Not only did they fail to acknowledge the vibrancy and diversity of American early film, but they generally failed to assess Porter's contributions within the context of world cinema, projecting America's post-World War I dominance backwards onto the pre-1912 era, when the French—first Lumière, then Méliès, and finally Pathé—often played more prominent roles. The more international, if still somewhat Eurocentric, outlooks of French historians such as Georges Sadoul have found Porter's place to be much more modest. Comparing Life of an American Fireman and one or two other Porter films to the better researched French and English cinemas and ignoring the dynamic of the American's development, Sadoul accuses Porter of imitating James Williamson's Fire! with Life of an American Fireman and Frank Mottershaw's Robbery of a Mail Coach with The Great Train Robbery . In so doing, Sadoul passes over the rich contexts of American cinema and popular culture, presenting a narrow, mechanistic analysis of Porter's development.[5] In truth, the observations of Jacques Deslandes and Jacques Richard are the most acute. They refrain from comparative judgments, admitting that one "must recognize one's own ignorance in the area and wait for serious research to be undertaken before one can make statements about the exploitation of the cinema [in America] between 1896 and 1906."[6]

As the field of cinema studies expanded in the early 1970s, superficial overviews of the pre-Griffith period became less and less acceptable. Making a tentative effort to put American early cinema in a larger context, Robert Sklar notes the need for a full-scale study of Edwin S. Porter, an absence this book seeks to fill.[7] More recently, a new generation of scholars has emerged that is interested in early cinema not because it was simply the precursor of classical cinema but because it was a practice with its own logic and integrity. Many of these scholars were working in isolation until the 1978 FIAF (Fédération Internationale des Archives du Film) Conference in Brighton, England, brought them together. There we met, exchanged papers, and saw hundred of films from the 1900-1906 era. Several of the papers dealt with Porter's work.[8]

Since the Brighton conference, an array of articles on early cinema have been written by participants and other historians. Many of these have been excellent, almost all have been provocative and useful.[9] Fewer books, however, have appeared to reflect this new level of interest. Several notable exceptions, Michael Chanan's The Dream That Kicks and a series by John Barnes, concentrate almost exclusively on the British cinema.[10] Others have added to the extensive literature already available on Georges Méliès.[11] No full-length study of American cinema prior to 1908 has been published as this goes to press.[12] Yet it is increasingly clear that a series of articles cannot replace sustained, book-length examinations of the period.

This present effort seeks to synthesize research derived from written primary source materials and viewings of films.[13] Writings of the period have been ex-

tensively consulted. Trade journals provided indispensable information even as they required painstaking efforts, for the motion picture industry had no specialized publication until 1906. Daily newspapers are another essential resource, one that would need many lifetimes to exhaust. Early motion picture catalogs contribute invaluable assistance, but are scattered across the United States. Collecting catalogs for this study thus led to an important subsidiary publishing project, the six-reel Motion Picture Catalogs by American Producers and Distributors, 1894-1908: A Microfilm Edition .[14] Manuscript collections are another key resource. The number of court cases involving motion pictures during this period was staggering. While these suits affected the industry's development, they also document specific cinematic practices. Porter testified often and was routinely asked to establish his professional credentials. Records, correspondence, and other materials at the Edison National Historic Site made possible a systematic study of the Edison Manufacturing Company and the work of its studio manager. There are gaps, however, and one of the most unfortunate was created by a fire that destroyed Porter's personal archive at the Famous Players studio on September 11, 1915.[15]

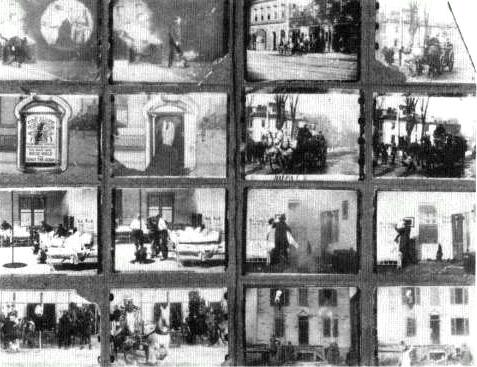

To balance this substantial reservoir of written materials, there are a large number of extant films. Perhaps 65 percent of the Edison subjects made before February 1908 can still be seen. Only scattered productions from 1894 to June 1897 survive, but the Paper Print Collection at the Library of Congress includes a large number of Edison films made between June 1897 and mid 1905. These films, deposited for copyright purposes as reels of paper photographs, have been restored and rephotographed back onto film by Kemp Niver.[16] The Kleine Collection, also at the Library of Congress, is a much smaller, but still significant, gathering of early, often uncopyrighted Edison films. In an unusually complementary relationship, the Museum of Modern Art has most of the Edison negatives from the period between late 1905 and February 1908. In the early stages of this project I had the opportunity to restore some Porter films, which the museum had already preserved, to their original order. When these were incomplete, surviving frame enlargements were filmed and inserted in their correct places, accompanied by titles taken from catalog descriptions. Very few Edison films made between February 1908 and Porter's departure in November 1909 are extant. There is reason to believe that the negatives for these films were shipped to Gaumont in Paris, where European release prints were made.[17] Perhaps they will one day be rediscovered. For the moment, the films made during this period—coinciding with Porter's loss of status both at Edison and in the industry as a whole—are lost.

This book is focused around three topics: (1) production and representational practices, (2) subject matter and ideology, and (3) commercial methods.

Modes of Production and Representation

My research began as I grappled with the assumptions of an earlier generation of film historians: since the "pioneers" discovered the inherent possibilities of film editing, the issue as these historians saw it was, who discovered which techniques, and when did given techniques first appear? It is evident that this basic perception remains entrenched to this day, albeit without so much of an individualistic slant. Yet this approach fails to recognize that early cinema's production methods were. radically different from our own. As shown in chapter 5, editing was a routine procedure during the late 1890s. It was primarily performed, however, by the exhibitor, who structured groups of short, one-shot films into sometimes quite complex sequences. Of course, editing was not as elaborate a procedure as it would become in later years, but its essential elements were clearly in place.[18] The history of early cinema must therefore consider the manner in which producers assumed control over the editorial function and the impact that this had on all areas of film practice, particularly the system of representation.

This history's first line of attention thus examines the dialectical interaction between cinema's methods of production and its mode of representation. Some of this seems obvious. When Edison developed a portable camera, new kinds of subject matter became possible. Conversely, the desire to undertake these new kinds of subjects encouraged the development of such a camera. Once the camera was in use, however, it allowed for the taking of images that could be sequenced into multishot stories. While the distinction between production and representation parallels Marxist distinctions between base and superstructure, changes in the superstructure clearly do not simply reflect those in the base.[19] Cinema's production practices have an impact on its representational system and vice versa.

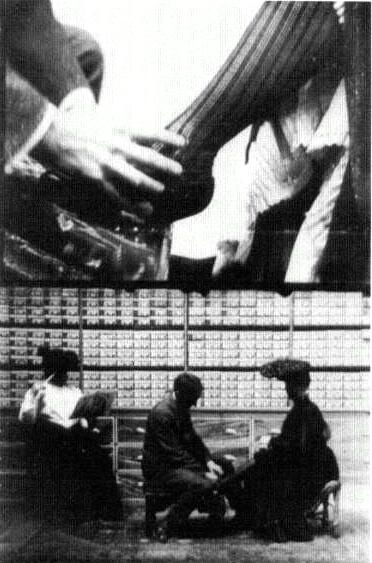

In the largest sense, cinema production involves three essential processes or groups: film production, exhibition, and reception (the production companies, the showmen, and the spectators).[20] While the films are a direct result of the mode of film production, they only have an impact within a changing framework involving the other two operations. The mode of exhibition comprises the showman's methods of presentation and his relation to the production company's films. The mode of reception or appreciation embraces the spectators' relationship to the exhibition and the ways in which they understand and enjoy the films as they are shown. All three processes experienced profound change and reorganization during the 1895-1909 period. The tendency among historians to equate film production to the whole of cinema has severely limited our understanding of motion pictures during the pre-Griffith era.

During its first fifteen years, the cinema's production methods experienced a series of rapid transformations. Insight into this process is facilitated by Harry Braverman's Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in Twen-

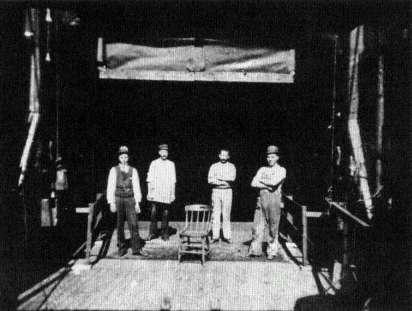

tieth Century America . Its look at changing modes of production outside the cultural sphere can readily be applied to film practice. According to Braverman, the centralization of work processes under one management is the fundamental step for subsequent transformations of production in advanced capitalism. As he remarks, "Control without centralization of employment was, if not impossible, certainly very difficult, and so the precondition for management was the gathering of workers under a single roof."[21] In the case of early film practice, control over creative decisions was scattered among different groups. Editorial decisions, as already mentioned, were initially the exhibitor's responsibility. Obviously it was not usually possible to bring producers, exhibitors, and spectators under one roof (although this occurred to some extent at the Eden Musee, where Porter worked in the late 1890s). Yet it was not only possible but highly desirable to bring certain practices under the control of a single management. Much of this volume examines the manner in which responsibility for many creative processes was more or less concentrated within the production company. This process of centralization, however, was not fully completed until the introduction of sound films.

As control over essential practices was centralized, the opportunity arose for a division of labor within the production companies. Here again Braverman provides a useful discussion of the economic logic of "the manufacturing division of labor" under capitalism. He is concerned not only with "the breakdown of the processes involved in the making of the product into manifold operations performed by different workers" but with the resulting degradation of work.[22] This division of labor was eventually manifested in the motion picture industry by what has become known as the studio system. Janet Staiger has ably explored this process of the division of labor within a similar theoretical framework, also informed by the work of Braverman.[23] While centralization of creative control was crucial to the formation of the studio system, other factors were simultaneously at play. The rapid expansion of the industry resulted in larger scales of production and created opportunities for dividing labor that capitalism was eager to exploit. The almost constant introduction of new technologies, as well as changes in the larger socioeconomic system, also altered production methods and influenced the reorganization of the workplace.

Porter's role in the process of centralization and specialization was complex and, as Noël Burch has noted, characterized by ambivalence.[24] While helping to concentrate crucial aspects of filmmaking within the production company, Porter opposed most aspects of the manufacturing division of labor. His resistance, in certain respects, is not unlike the worker resistance examined by David Montgomery in Workers' Control in America .[25] Although many in the industry—most notably the projectionists—reacted angrily to the rapid degradation of their work life, this volume focuses on the resistance of Edison studio personnel, particularly Porter, to specialization and hierarchy.

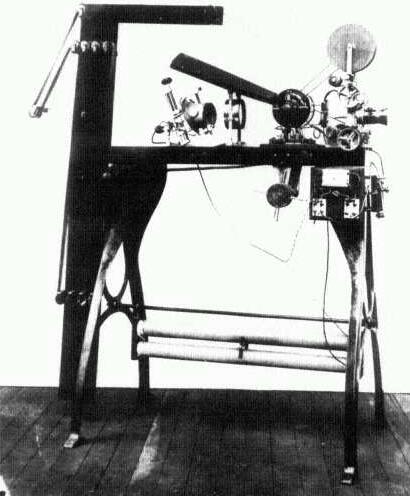

From today's perspective, Porter was an extraordinary individual who mas-

tered all phases of film practice. He not only shot a range of news subjects and actualities but produced a variety of successful dramas and comedies. Moreover, he not only directed them, but worked on the scenarios, acted as cameraman, and edited the film—he even developed his own negatives. He designed and built studios, then outfitted them for operation. He devised projectors, perforators, and cameras. He remodeled Edison's projecting kinetoscope, turning it into a first-rate projector, and went on to build prototypes for the Simplex projector, which became the industry standard during the 1920s and is still considered by some to be the best machine of its kind ever made.[26] Yet Porter was not—as one might say of D. W. Griffith, Erich yon Stroheim, or Charles Chaplin—a one-man show. Throughout his career and in many different areas, he worked collaboratively and in a nonhierarchical fashion. In short, his whole method of work was incompatible with the studio system.

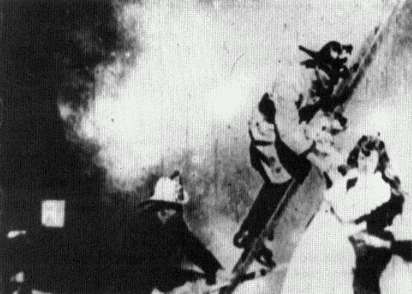

Initially, the radically different formal structures of pre-1907 films attracted me and other scholars to this era of motion picture practice. The problem of cinematic representation, in recent years one of the focal points of film studies, assumed wider significance in the light of these viewings.[27] Here again, Porter clearly played a central role. He was one of several filmmakers who elaborated the mode of representation that flourished in the early 1900s, only to disintegrate as cinema became a form of mass entertainment. The dialectic between production and representation shaped the Edison films on which he worked. As the production company began to assume control over editing, Porter and his colleagues developed new kinds of continuities between shots. Life of an American Fireman (1902-3)—with its overlapping actions, its narrative repetition, and malleable pro-filmic temporality—is particularly illustrative. (The film is analyzed extensively in chapter 7.) Here and in other instances the Edison group applied this new system of continuity in its most extreme form. Such representational strategies proved so successful that they justified and helped to generalize this development. When the viability of these techniques faded, however, Porter refused to give them up. Porter's failure to adopt the emerging proto-Hollywood mode of representation in 1908-9 (embraced by Pathé, Vitagraph, and particularly D. W. Griffith) caused his fall from grace even more than his resistance to the transformation in production.

Although a series of transformations provide the framework for this study, important aspects of early cinema remained relatively stable. In fact, such qualities characterize and define early cinema. Viewers understood and enjoyed screen images in several distinctive ways. Audiences frequently viewed a film in relation to a narrative that they already knew. The narrative might be based on a front-page newspaper item, a play, or a popular song. If spectators were ignorant of the necessary referents, they could make little sense of the film. In other instances, exhibitors facilitated audience understanding of the images with a sound accompaniment—for instance, with a lecture or by speaking dialogue from behind the screen. While some early films required neither special knowl-

edge from spectators nor active intervention by the exhibitor, such situations were neither preferred to other audience-screen relationships nor dominated screen practice. Only in the nickelodeon era did cinema emerge as a cultural practice in which neither the exhibitor's intervention nor special knowledge on the part of the audience was necessary to a basic understanding of the narrative.[28]

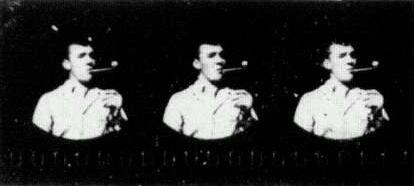

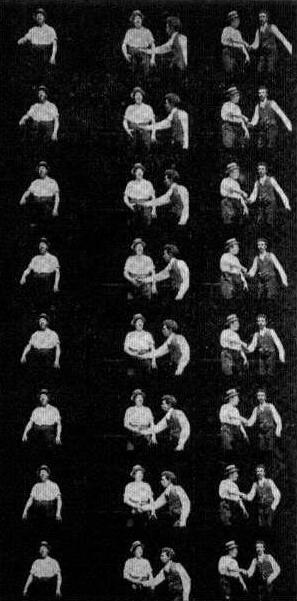

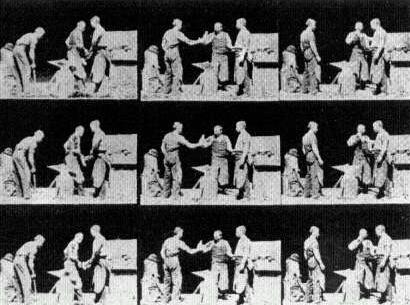

Edison films, like early cinema in general, had a recognizable and coherent system of representing the world. As Tom Gunning has pointed out, performers or subjects in front of the lens characteristically played to or displayed themselves for the camera and an imagined audience.[29] Such an approach might involve tableau-like, static compositions or a confrontation with the camera/ spectator (for instance a cavalry charge directed at the lens). Early fiction films likewise more or less adopted a diagrammatic relationship to the real world, one that limited the degree of verisimilitude. Thus depictions of space and time were generally conventionalized and schematic. Sets suggested a locale rather than creating the illusion of a real world. Condensations of time and action within the shot were commonplace. (Perhaps more surprising, many actuality films achieved similar effects through jump cuts or camera stops.) The acting style likewise embodied highly conventionalized gestures that expressed forceful emotions. The periodic reliance on pantomime by early filmmakers further intensified these tendencies. These interrelated elements of a representational system will be called presentational , appropriating a term from theatrical criticism that is used to describe similar methods that predominated in the theater during much of the nineteenth century. This presentational approach is, moreover, evident in a wide array of other cultural forms from the same period (painting, photography, comic strips).

If presentationalism usually dominated early cinema, it was not an absolute. Films before Griffith were generally "syncretic": they combined and juxtaposed different kinds and levels of mimesis. Thus verisimilar elements could exist side by side with presentational ones. A real pot hangs on a wall next to another painted on the backdrop. A two-dimensional, pasteboard cabin may be placed in the middle of real woods. Such syncreticism operated between shots as easily as within them. A film like The "Teddy" Bears uses a set for one exterior scene and outside location footage for another. Clearly this is different from the consistently represented "seamless" mimetic world of most later cinema.

In examining the interaction between production and representation, it has been advantageous to place early cinema in the larger framework of screen practice. When looking at cinema's beginnings, most histories use some variation of a biological model of development. In its crudest form, this model suggests that the medium was born, grew up, learned to talk, and (having mastered the language of cinema) finally began to produce great works.[30] In any case, cinema moves from the very simple, the naive, and the unformed to the more

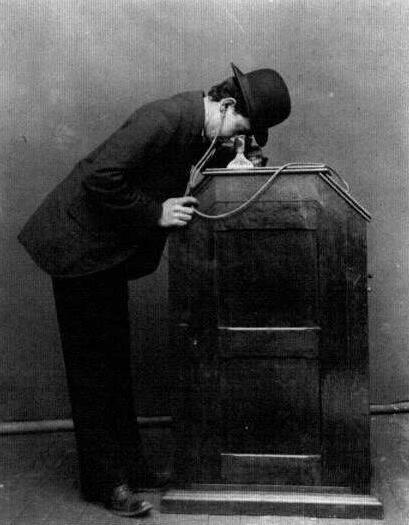

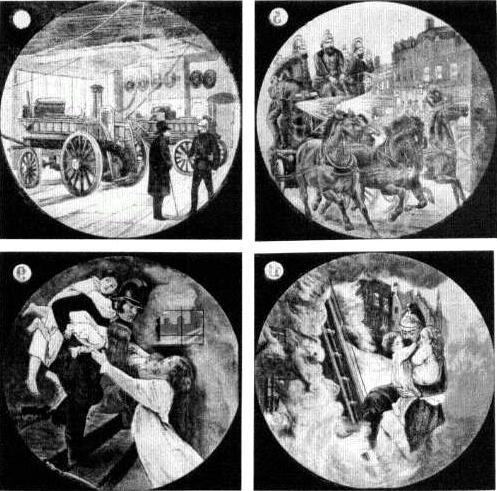

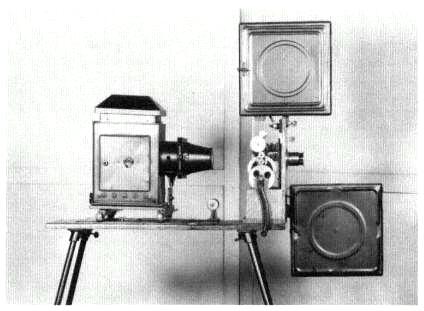

complex and sophisticated. More recently, a number of historians have seen cinema as emerging out of a diversity of precursors to become a culturally and economically determined form of expression.[31] Both these historical models view the invention of cinema as a starting point. In contrast, a history of screen practice considers projected moving pictures as both a continuation and transformation of magic-lantern traditions in which showmen displayed images on a canvas and accompanied them with voice, music, and sound effects. It is worth noting that this notion of historical continuity was commonplace during the first ten years of cinema. As Henry V. Hopwood remarked in 1899, "A film for projecting a Living Picture is nothing more, after all, than a multiple lantern slide."[32]

The history of projected images and their sound accompaniment has its origins in the mid seventeenth century. The beginning of screen practice does not, however, privilege a moment of technological invention—such as the invention of the magic lantern or the cinematographic apparatus—but rather a fundamental transformation in the mode of production. Screen practice began in the 1640s when the process of projecting images was no longer concealed from the unsuspecting viewer. Instead of being an instrument of terror and magic known only to a select few, the projecting apparatus became an instrument of cultural production that was known to all.[33] The history of screen practice prior to 1896 has been neglected by film historians. Although it remains outside the domain of this study, it provides a necessary framework for understanding the processes of industrial transformation examined in this volume. Pre-cinema exhibitors, for example, were the ones who had ultimate control over the editing process; they acquired slides from a variety of sources (including often making the slides themselves) and juxtaposed one projected image against another. The new technology of motion pictures helped to transform the screen, facilitating a shift in both narrative responsibility and authorship from exhibitors to the production companies.

While the interrelationship between production and representation is key to understanding the changes in editorial and narrative practices, its impact extends beyond these areas. The production of Edison films within a white, "homosocial," male world affected the choice of subjects as well as the ways in which these were depicted.[34] Again and again, when early filmmakers expressed a nostalgia for a lost childhood, it was boyhood they recalled and boyhood that they visualized. Such biases shaped the portrayal of women and blacks in particular. The complex relationships between work and leisure at the turn of the century, which Roy Rosenzweig and Kathy Peiss have astutely explored, finds a profound conjunction in the early film industry.[35]

Subject Matter and Ideology

A second line of attention in this study focuses on subject matter and its treatment in Edison films. Here cinema is related to other cultural texts and

practices from which film production appropriated images, gags, and stories. At first they were almost exclusively from the world of masculine amusement, of dancing girls and prize fights. Output was soon adjusted to accommodate "heterosocial" amusement in which women and men participated as spectators. Porter's earliest films, often made with George S. Fleming or James White, served a variety of needs. Some were incorporated into travelogues, perhaps the most popular form of pre-cinema screen entertainment. Others documented vaudeville acts. Most functioned as a visual newspaper. The newspaper in turn-of-the-century America, then one of the few forms of mass communication, had a profound influence on other cultural practices, not least of which was the cinema.[36] Individual films had strong ties to different types of journalistic features: news stories, editorial cartoons, human interest columns, and the comic strip. Even fight films and travel scenes were not inconsistent with cinema as a visual newspaper, for the papers covered both sports and travel. As with the newspapers, the purpose of cinema at the turn of the century was to inform as much as to entertain. By 1902-3, cinema was losing its efficacy as a visual newspaper and was reconceived primarily as a storytelling form. For most production companies, this shift meant that cinema's new role was increasingly to amuse. A significant exception to this pattern involved a group of Porter films made between November 1904 (The Ex-Convict ) and December 1905 (Life of an American Policeman ). These had an explicit social concern. Often Progressive in their politics, they presented a complex, sometimes contradictory, and finally conservative vision of the world. Only at the end of 1905, when the nickelodeon era was under way, did Porter accept the notion of cinema as simple amusement—a shift that may well have been influenced by commercial decisions made by Edison executives.

As the proliferation of storefront theaters turned cinema into a form of mass entertainment, traditional guardians of American culture and public morality protested against subject matter they often considered sensationalistic and corrupting. Porter and the Edison Company found that the broader their audience, the narrower the boundaries of acceptable subject matter and its treatment became. While Thomas Edison and his managerial staff actively supported the articulation of certain "standards" in the face of mounting protest, propriety was occasionally violated—at least in the eyes of some critics—even within the Kinetograph Department. The solution that finally won the support of Edison and his executive Frank Dyer was to defuse criticism by supporting a National Board of Censorship. For these entrepreneurs, the issue was not freedom of expression but maximizing profits within a mass communication system.

Films expressed larger social, political, and cultural concerns even as they sometimes served a personal, reparative function for the filmmaker.[37] The ideological orientation of early cinema has been much discussed. Noël Burch has argued that in form and content these films reflected "the infantilism of the working classes. "[38] Others, such as Robert C. Allen, have seen early cinema as

addressing a middle-class audience and presumably reflecting its ideological orientation.[39] Certainly, America has been called a middle-class country, and this is nowhere more apparent than in its cultural products. The middle class, however, was not a single, unified group, but made up of diverse and even contradictory interests. Harry Braverman makes a useful distinction between what he calls the old and the new middle classes.[40] The old middle class was largely outside the labor-capital dialectic in that it neither sold nor bought labor power on an extensive basis. The new middle class of employees, however, functioned within this labor-capital dialectic, assuming in certain respects the position of the working class and at other times that of employer. Although Porter was a member of the new middle class, his attitudes were shaped by his earlier experiences in Connellsville, Pennsylvania, where his family and then Porter himself had been small businessmen. His films reflect a personal distaste for the workings of large-scale, impersonal capitalistic enterprises: particularly The Ex-Convict, The Kleptomaniac , and The Miller's Daughter . This was not a uniquely personal vision so much as the principal cinematic expression of a more general outlook that then found frequent cultural expression.

In looking at Porter's work, one finds a remarkable ideological unity. The filmmaker's unhappiness with advanced capitalism extended beyond the subject matter of his films and included his resistance to the manufacturing division of labor that arose in the wake of the nickelodeon era. Here again, his approach was that of the old middle class. This did not mean that he wished to work alone, but that he preferred to work with others in an informal, collaborative manner. Finally, the representational system that Porter championed reflected the same old-middle-class orientation, not simply because it embodied a specific set of working methods and prevented the new, impersonal system of mass entertainment from operating effectively, but because it usually depended on audiences sharing his basic cultural frame of reference. Within this framework of production and representation, Porter conducted a far-reaching exploration of cinema's manifold possibilities.

Commercial Methods

Commercial strategies both at Edison and within the industry as a whole constitute a final level of attention. One popular approach to business activities in the film industry has been based on industrial organization economics, "an economic theory of technological innovation, which posits that a product or process is introduced to increase profits in three systematic phases: invention, innovation and diffusion."[41] However, an approach focusing on business strategies provides an insufficient basis for constructing a history of American cinema (or any cultural practice). Moreover, business strategies for the 1895-1909 period were concerned with innovations in many different areas, including sub-

ject matter, modes of representation, marketing, and production. It is not clear why the introduction of technology should be privileged in such a history.

Although this study deals extensively with management decisions that had as their goals the maximization of profits, the history of early cinema suggests a more appropriate framework for analysis: the examination of business strategies in relation to changing modes of production and representation rather than simply in terms of technology. This approach is dialectical rather than cyclical, and it rejects the notion of technological determinism implicit in industrial organization economics. Technology is an essential aspect of the mode of production, but it is often not the crucial factor in accounting for change and new economic opportunities. The nickelodeon era was made possible by the production of an increasing number of longer films that could be used interchangeably by theaters. Vitagraph's and Pathé's rapid expansion in film production after 1905 was based on their astute assessment of this new development. In contrast, the Edison Company's failure to respond effectively and quickly significantly weakened its position in the industry. A methodology that translates technological innovation directly into business practices risks patterning information in ways that render it inaccurate.[42]

Relations between film producers and exhibitors are central to an understanding of commercial strategies and disputes within the industry. In the film business, tension has always existed between these two groups as each attempts to achieve dominance within the industry. This conflict has been manifested characteristically in vertical expansion or integration as exhibitors moved into film production or producers into exhibition. Since the advent of the nickelodeons, producers and exhibitors have tried to strengthen their positions by controlling distribution. Sometimes independent distributors have been able to function at this interface. This was the case when the nickelodeon era began—although even then exhibitors and producers owned important exchanges. Within a few years, however, producers were once again seeking to exercise control over this important commercial function. Not surprisingly, distribution has become a key branch of the film industry.

The motion picture industry did not, however, operate as a self-contained entity. One area in which the larger society had a crucial impact on the industry's commercial structure was through the judicial system. Thomas Edison constantly relied on legal action to protect or expand his stake within the industry. Between 1898 and 1902, he had considerable success with this approach and managed to put many competitors out of business. Others were allowed to continue under a commercial licensing arrangement designed to benefit the inventor. Facing setbacks in the courts between 1902 and 1906, "the Wizard of Menlo Park" lost his position as the dominant producer. In 1907, however, his motion picture patents won significant judicial recognition, encouraging the inventor to establish a "trust," a combination of leading production companies subsequently known as "the Edison licensees." The resulting trade association

hoped to control the American industry. When it failed to accomplish this, the organization was expanded to include the patents and commercial clout of rival concerns. The resulting Motion Picture Patents Company was formed at the end of 1908 and put into full operation early in 1909. Its goal was to assure a high level of profit and raise barriers against those who would otherwise have entered this profitable field.

The moving picture was only one of several products exploited by Thomas Edison and his executive staff during this era. The Kinetograph Department, where Edison located his film activities, was part of the Edison Manufacturing Company, which also produced batteries, x-ray machines, and dental equipment. Edison's National Phonograph Company, which shared the same top executives as the Edison Manufacturing Company, was more profitable and closer to the inventor's heart. The inventor's storage battery, Portland cement, and iron ore-milling ventures, required large infusions of capital—sapping money from other Edison-operated ventures, including film. (In the case of Portland Cement and iron ore milling, Edison and his investors lost large sums of money.)[43] The motion picture business, while important, was not the sole focus of attention it was for most of Edison's rivals. The inventor's film business also suffered from frequent turnovers in management-level personnel. Porter worked under four different department heads: James Henry White (October 1896 to November 1902), William Markgraf (December 1902 through March 1904), Alex T. Moore (March 1904 through March 1909), and Horace G. Plimpton (March 1909 until August 1915). William E. Gilmore served as vice-president and general manager of the Edison Manufacturing Company from April 1895 to June 1908 and actively participated in all important decisions during that period. He was replaced by Frank Dyer, Edison's chief patent lawyer, who reorganized the Kinetograph Department and the entire film industry, hastening Porter's demotion from studio manager to technical expert in February 1909. These were the people who principally determined Edison business policy, an area in which Porter appears to have had little say.

Business considerations constantly influenced what Porter produced. Economic pressures based on the pattern of film sales were determining factors in the shift from actualities to acted "features." Certain films—for instance, Porter's remake of Biograph's popular hit Personal —were first and foremost commercial weapons used to undermine the success of competitors. The decision to rely on "dupes,"[44] calculated on the basis of financial gain, adversely affected the attention paid and resources available to original productions. Edison business strategies were formulated within the framework of the industry's overall development, and it is only within this context that Porter's work can be fully appreciated.

This study is organized in a chronological fashion, broken down into chapters that emphasize important changes from the introduction of cinema as a

screen novelty to the establishment of new practices still associated with modern cinema. Deciding upon the precise moment when these changes occurred as the basis for chapter divisions demanded difficult and sometimes arbitrary decisions. Individual chapters often use specific events and circumstances in Porter's work and Edison Company policy as points of division. While a slightly different breakdown could be offered, it is not so much specific dates and divisions that are important as the general pattern of development.

This book is designed to serve several functions above and beyond providing a history of Porter and Edison film activities between 1894 and 1909. It is meant to be used in conjunction with screenings of the films. If, as this study argues, films were often understood within a framework of specific knowledge or with the assistance of a narrator, then today's spectators need that same knowledge readily at hand. If the films are to be fully appreciated, they not only need to be preserved and made available to the public (a function ably performed by the Museum of Modern Art and other institutions), but the context in which they were seen has to be partially reconstituted. Therefore, for example, the song "Waiting at the Church" has been reprinted in its entirety so the reader can see Porter's Waiting at the Church , and enjoy the correspondence between the two. Selected catalog descriptions have been included, not only to make available key film narratives—including information that could never be derived from a silent viewing of the film—but to provide descriptions that today's students and historians can use to create their own lectures to accompany the films. This volume also serves as a companion to the documentary film Before the Nickelodeon: The Early Cinema of Edwin S. Porter . All the quotations used in the documentary appear in this volume with the appropriate references. A finding aid for these appears in appendix C. In a few cases, recent research has uncovered new information that has made small corrections necessary. The book and the film are designed to complement each other.

This volume also forms part of a larger study, a trilogy of books, I have undertaken on early cinema in America. High-Class Moving Pictures: Lyman H. Howe and the Forgotten Era of Traveling Exhibition, 1880-1920 , written with the collaboration of Carol Nelson and published by Princeton University Press, looks at the activities of America's traveling motion picture exhibitors, particularly Lyman Howe, and also analyzes cultural divisions within middle-class audiences. The Emergence of Cinema in America , a historical overview of American cinema to 1907, published by Scribner's/Macmillan, is the first book in the ten-volume American Film History Project edited by Charles Harpole. Finally, a filmography of Edison films, including extensive documentation, is in preparation. Early cinema, like most cultural phenomena, is not easily grasped in all its complexity. I hope that this body of work, in conjunction with the accomplishments of colleagues and fellow scholars, will enhance people's appreciation for this formative period in motion picture history and contribute to the general knowledge of American culture.

2

Porter's Early Years. 1870-1896

To understand the underpinnings of Edwin Stanton Porter's approach to filmmaking, we must turn to the world in which he was born and spent the first twenty-three years of his life.[1] As with any individual, his subsequent activities were a complex response to these formative experiences—in his case, one that involved significant continuities. With his films often nostalgically longing for a lost past and a romanticized childhood, a biographical study must reassert the concrete character of that world. Porter grew up in Connellsville, Pennsylvania, a small town fifty miles southeast of Pittsburgh. Its population in 1870, the year of his birth, was 1,292. Despite this modest size, it was not a rural community but a small industrial center.

In the 1870s Connellsville functioned principally as a railroad repair center.[2] By the end of the decade, it was producing large amounts of coke—processed coal used primarily for making steel. Connellsville coke soon became known as the best in the country, and the area depended on this industry for its prosperity. Connellsville more than doubled in size by the 1880 census to 3,615 inhabitants. Although the town had its share of small businessmen, including Porter's father, his extended family, and friends, the environs were dominated by the economic realities of large-scale production. The often-troubled relationship between absentee owners of extensive coke works and a large number of "cokers"—workers who mined the coal and tended the coke ovens—was a fundamental aspect of Connellsville life. Connellsville also boasted various forms of commercial popular culture, in which Porter participated. This environment provided Porter with the experiences, presuppositions, and skills that were to facilitate, shape, and influence his subsequent work as a filmmaker.

The Porter Family

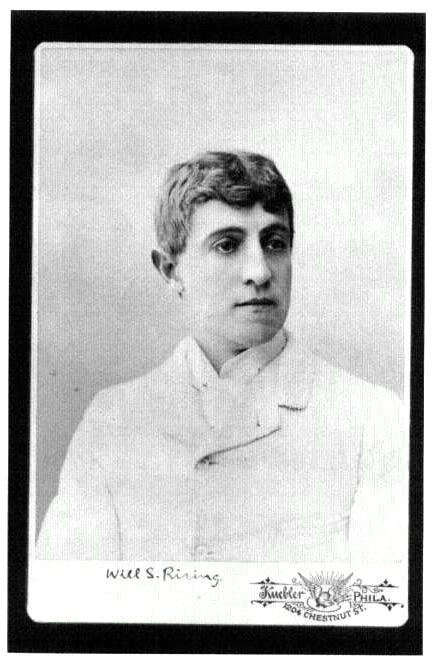

Edwin S. Porter was born on April 21, 1870, to Thomas Richard and Mary (Clark) Porter. His namesake was Edwin M. Stanton, a Democratic politician from Ohio who served as Abraham Lincoln's secretary of war. This name was Porter's own, somewhat later choice, for his parents called him Edward; and as a short chubby boy, he went by the nickname of "Betty."[3] The youngest member of his family for ten years, Ed ultimately became the fourth of seven children, the others being Charles W. (born 1864), Frank (1867), Mary (1868), Ada (1880), John (1883), and Everett Melbourne (1889). His father, Thomas Porter, was one of at least seven brothers who grew up in nearby Perryopolis. Their father, Edward's grandfather, was a stone cutter.[4] After the Civil War, several brothers moved to Connellsville, which was expanding with the growing coke trade. In the 1870s Thomas's older brother Henry, also a stone cutter, became Connellsville's postmaster, a much-sought-after position, which kept his children employed as postal clerks. Through combined financing and partnerships, the Porter clan established or invested in several local enterprises.

Porter's father was a small businessman often dependent on his more successful siblings. When Edward was born, Thomas Porter was working as a cabinetmaker. By the following year he was running Porter & Brother, a furniture store and undertaking establishment owned by his older brothers. The only funeral service in town for the next seven years, Porter & Brother rented furniture for these and other occasions. As Connellsville expanded rapidly in population, the firm began to sell factory-made furniture, for which it also enjoyed a local monopoly. By late 1877 the business was jointly owned by Thomas and John Porter, with John's son Everett Melbourne acting as co-manager. Four years later, John Porter was reportedly worth $50,000, while "Thomas Porter, the managing partner, has very little outside of his investment in firm but is economic, industrious and temperate."[5]

Thomas Porter assumed control of the undertaking business in 1888 when Everett Melbourne, who had been increasingly ill with consumption, died in February, a month after his father. Edward's oldest brother, Charles W. Porter, was soon brought into the family business, renamed Thomas Porter & Co. The local newspaper glowingly described the firm shortly after Thomas had taken full charge:

. . . Of this house it is only fair to say that they have probably done as much toward accelerating the commercial activity of the town by their enterprise as any other concern within its limits. They occupy part of the three-story building of Soisson's Block on Main Street. Their room is of spacious dimensions, being 20 × 70 feet in extent, with a large manufacturing room and other necessary outbuildings in the rear. They unquestionably carry as large a stock as any to be found in the country, including dining-room, reception and drawing room, parlor, library and bedroom suites of every description. In their undertaking department they are equally well equipped, carrying

caskets, coffins, etc. of all grades and sizes. They own two fine hearses, one for children and one for adults, besides a large and beautiful funeral car. Mr. Thomas Porter is especially fitted by nature and practical experience for the delicate duties devolving upon him of the embalming of the dead.

The house was established eighteen years ago under the style of Porter and Brother. This was in a small way, but by diligence in business and energy, fair and honorable dealing, this house now represents the very best class of houses in Western Pennsylvania in the line of fine furniture and funeral directors.[6]

By the early 1890s Charles Porter and his father may have had a falling out: the son set up his own company, eventually forcing Thomas Porter into retirement.[7]

Thomas Porter's success was more modest than his brothers'. Shortly after Edward was born, Samuel, John, and Henry Porter formed a partnership with three other Connellsville men to conduct a general foundry and plow manufactory. The firm added a new branch in 1873 for forgings and machine work. By 1880 some of the partners were bought out and the firm became known as Boyts, Porter & Company. Its most successful product, the Yough pump, captured a substantial market among mining companies across the country. The business flourished and became one of the two major manufacturing establishments in Connellsville during the 1880s.[8]

Edward Porter had other relatives living in Connellsville. His cousin William Porter had a large family and carried on the family trade as a stone cutter.[9] His mother's family was also from the borough. His uncle William Clark sometimes served as justice of the peace, and a great great grandfather, Abraham Clark, had signed the Declaration of Independence. With several aunts likewise living in the area, Edward was related to a significant portion of the population.[10]

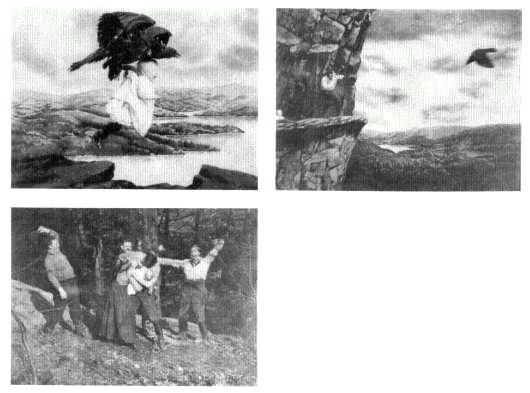

Family life was of central importance to the Porters and other Connellsville residents. The disintegration of a family through death or separation was the worst tragedy a person could suffer, according to the Keystone Courier , which often featured such incidents on its front page.[11] When Henry Porter learned of his eldest son's death, he suffered a stroke, from which he never fully recovered, dying less than two years later.[12] After Everett Melbourne's death, Thomas Porter named his next child after this deceased nephew. Thomas Porter's role as funeral director meant that death and loss of family constantly impinged on the Porter household. No doubt this left a strong impression on young Edward, most likely shaping his development from an early age. Moreover, loss was something that Porter experienced very directly later in his life, when attempts to start a family would be repeatedly frustrated as his wife suffered a dozen miscarriages.[13] In reaction, the filmmaker became preoccupied with the family unit. Although family-centered dramas were common in early-twentieth-century popular culture, Porter drew on such narratives with remarkable frequency. From Life of an American Fireman (1903) to Rescued from an Eagle's Nest (1908), it is the saving of the parents' only child (or in the case of Lost in the

Alps [1907], their two children) that dominates and brings relief. This perpetually happy conclusion stands in stark contrast to Porter's own life. He was not so fortunate, and his inability to have children contributed to his growing reclusiveness and eccentricity in later years.[14]

While Porter's family was part of Connellsville's community of small businessmen and shopkeepers, the town's merchants are of additional interest in that four of its members eventually purchased the rights to "Edison's Vitascope" in 1896.[15] J. R. Balsley was a prominent builder with a lumber mill. F. E. Markell owned drugstores in Connellsville, neighboring New Haven, and East Pittsburgh. R. S. Paine ran a shoe store and had some additional capital invested in other ventures, including a Florida orange grove. Cyrus Echard worked in the coal trade. These local merchants were a closely knit group. They served together on committees, celebrated each other's birthdays, and hired each other's children to clerk their stores. J. R. Balsley's son, Charles H. Balsley, was Ed Porter's best friend. In 1890-91, both worked for the slightly older J. F. Norcross, who had inherited his father's tailoring establishment. The three bachelors formed a youthful triumvirate, not only at work but in their occasional pursuit of adventure. Work and leisure were interwoven in a single, all-male environment. Their work life, with its informality and equality, was in marked contrast to the coke industry's regimentation and hierarchy. After Norcross married and moved west in the fall of 1892, Porter opened his own business as a merchant tailor.[16]

The coke industry impinged on every aspect of daily life in Connellsville, expanding from 5,000 ovens in 1880 to more than 17,000 by 1893.[17] In 1880 a visitor found his entrance into town "lit up by the lurid glare of coke ovens, while the stars were obscured by the murky smoke."[18] With crowded streets, Connellsville was a "business town where everyone seemed to have an object in view," he observed. "Here and there a drunken man reeled along, and from various drinking houses came the noise of revellers." As he passed along the borough's main thoroughfare he saw "the reflected light of the Pittsburg and Connellsville Gas, Coal and Coke Company's ovens. The ovens number 250, the longest continuous line of ovens in the region." The fumes destroyed nearby vegetation and damaged crops and fruit trees. Industry triumphed over agriculture, and when farmers sought redress through the courts, the justice system finally ruled in favor of the coke operators.[19] Coal mining, tending coke ovens, and running the trains was dangerous work. While the large number of industrial accidents and deaths owing to "consumption" and bad air contributed to the prosperity of the Porter undertaking establishment, the fumes also affected the Porters' health. As a child, Edward suffered bouts of pneumonia aggravated by the bad air.[20]

Although Connellsville's merchants prospered when the coke industry did well and suffered when it did badly, those who owned the industry and those

who worked in and around it were removed from many aspects of small-town life. Cokers lived in company housing and bought most necessities from company stores. Their alienation from the local community increased after 1879 when "foreign," that is, Eastern European, labor was brought into the region.[21] The formerly strong kinship and ethnic ties between the cokers and the townspeople began to break down as a result. By 1889 Henry Frick controlled the region's coke trade, and the coke works were owned by distant corporations that had little direct interest in the local communities.[22] For local small businessmen—members of the old middle class—the fundamental opposition was between themselves and mammoth corporate entities represented by the coke industry, not between labor and capital. To a significant extent, these men worked outside the labor-capital dialectic and saw it as a foreign and undesirable intrusion.

Dependent on the coke works for their general welfare, the small-town merchants often felt helpless. Their anxiety increased whenever tension erupted into class warfare. Strikes occurred throughout Porter's youth: in 1877, 1879, 1880, 1883, 1886, 1887, 1889, and 1891.[23] The strikes of 1886 and 1891 were particularly brutal and protracted. The owners sought to break these actions by importing scab labor, thereby forcing strikers to resort to violence to keep the mines closed. The coal operators in turn hired ex-policemen and Pinkertons to protect their interests. In the strike of 1891, cokers were killed and the National Guard was called in. Porter observed a mounting pattern of violence as the coke industry expanded and Frick consolidated his position within it.

The difficult relationship existing between Connellsville's old middle class and the coke industry was apparent in the Democratic Keystone Courier , which spoke primarily for the town's small businessmen, its principal advertisers. Its pages contained editorials preaching against strikes—opposing the operators who provoked them as much as the miners who undertook them. The Courier constantly called for arbitration and the avoidance of conflicts that disrupted business, not only the coke business but the merchants'. It saw itself as an impartial judge in such situations and felt free to lecture both sides on their responsibilities. The paper and the old middle class saw themselves as representing public opinion and providing a moral weight that should be decisive. In the midst of "the most general strike ever inaugurated here," the Courier asserted that "unbiased observers unite in the opinion that if the latter [the workers] return to work, public feeling will compel the former [the operators] to grant the advance asked and remedy the abuses complained of—abuses that even the operators admit do exist."[24] Imbued with this attitude since childhood, Porter later expressed similar desires for the reconciliation of labor and capital. This moral judgment claiming to operate objectively above the conflict is apparent in a number of his films, including The Ex-Convict (1904).

Despite being caught in the middle of the labor-capital conflict, Con-

nellsville's merchants generally favored the miners, who were their real or potential customers—and often relations or members of the same church. Certainly it was in their self-interest, for when the coke workers were fully employed and well paid, local business prospered too. During the strike of January and February 1886, a temporary alliance was forged between the miners and many of the merchants. The store owners donated food and clothing, while the miners demanded an end to the "pluck-me's"—company stores that advanced credit to their employees, making money by inflating prices and depriving local merchants of revenues they might otherwise have expected. Significantly, the strike was won by the workers, although the company-store issue was not resolved.[25]

There were limitations and contradictions in the Courier's support for the working class. To retain the paper's support, the coke workers had to stay within the law even if operators brought in scab labor. Attempts by workers to meet these threats with violence or the destruction of company property were strongly condemned. Socialists and other radical elements were anathema. Old-middle-class support for the working class therefore functioned within a limited framework. Within similar limits, Porter's sympathies for the working class are evident in films such as The Kleptomaniac (1905).

Growing up in Connellsville, Porter apparently adopted the strong prejudices that his family and friends held against many immigrant groups. During the 1880s the town's native white population developed a deep-seated antipathy for Eastern European immigrants. The first explosion of hostility came in February 1883, when an open letter accused the "Hated Hun" of barbaric acts. "One of the most degrading influences brought to bear on our community is the indiscriminate importation of Hungarian serfs and their employment on public works, in preference to good located citizens who are willing and can perform more and better labor for the same pay," this "Appeal to the Christian Public" claimed.[26] The Courier , at first appalled by the vituperative attacks, soon adopted the same terminology. Such hostility focused on the "not overly clean habits and queer customs" of the "Hated Huns." Native workers were disturbed by a common sight: "their women in a state of semi-nudity at work in the . . . blinding dust of a coke yard forking the product of the ovens."[27] By 1886, 25 percent of the cokers were Poles, Hungarians, and Bohemians, while another 10 percent were Germans and Prussians.[28] These workers were initially seen as the tools of the operators who brought them to their mines. During the strike of 1886, however, they proved to be more militant and radical than their domestic counterparts. When they rioted to maintain the effectiveness of the strike, the "Hated Huns" were characterized as lawbreakers and dangerous radicals.

Porter was almost certainly a member of the nativist Order of United Mechanics, which sprang up to challenge the disruptions caused by the protracted, violent strike of 1891. A member of this secret beneficial association had to be a native-born American, of good moral character, believe in a supreme being,

favor the public school system, oppose the union of church and state, and be capable of earning a living.[29] Edward Porter's friend and employer, J. F. Norcross, and his best friend's father, J. R. Balsley, sat on the order's financial committee, which organized a parade of its membership in Connellsville on July 4, 1891. The Courier announced, "The Biggest Fourth in the History of the Town Promised by American Mechanics, The Red Flag of the Socialists Recently Displayed in the Coke Regions Stirs the Blood of the UAM's. . . . They are anxious to show the foreign rabble who rally under it how well American labor loves the American flag."[30] J. R. Balsley, one of the order's most active members, gave a Memorial Day speech denouncing the troublemakers.

We are sorry that there is in our land today an element of discontent, but when we know that this class is made up of the scum of foreign nations and a few weak minded of our own land, there need be little [to] fear from this quarter. These men would not be satisfied with any laws that human skill could enact. If it was possible for them to enter heaven, they would at once want to change the ruling of the divine master.[31]

The ethnic stereotypes in Porter's The Finish of Bridget McKeen (1901), Cohen's Fire Sale (1907), and Laughing Gas (1907) were consistent with the attitudes Porter developed in the western Pennsylvania coke region. They had many counterparts in popular culture and reflected the general ethnic and racial prejudices of most native-born whites.

Porter and Connellsville's Cultural Life

Porter has been portrayed by some historians as a naïf who "had no background or experience in art" and so was unaware of the implications of his work.[32] This is certainly inaccurate, for he was an active participant in Connellsville's cultural life at a time when it was being fundamentally transformed. During the 1870s commercial, popular culture had come to Connellsville only infrequently. The churches, public schools, and the local press were the principal cultural institutions. For an evening's entertainment, a minister might deliver a light-hearted lecture on subjects such as "Fashion" or the local debating society argue topics such as "Can the existence of God be proven without the aid of divine revelation?" or "Should foreign immigration be prohibited?"[33] Performances by touring theater groups were rare and not well attended. When Thorne's Comedy Company came to town in April 1880, twenty people were in the audience, and the play was dismissed as "worse than mediocre." This, the first company to be reported in the Keystone Courier , did not survive its Connellsville performance and was disbanded.[34] The next troupe to visit the borough, the Stenson Comedy Company, did not pass through town for another eight months. In 1880 residents were dependent on their occasional visits to Pittsburgh for most of their theatrical entertainment.

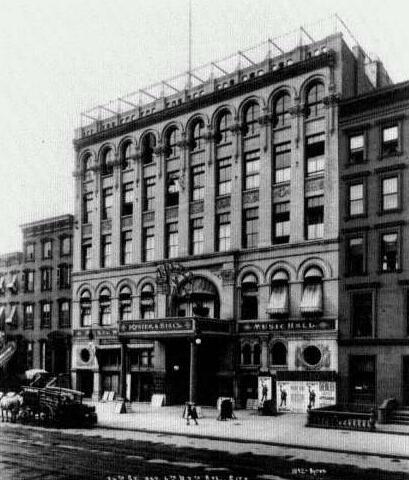

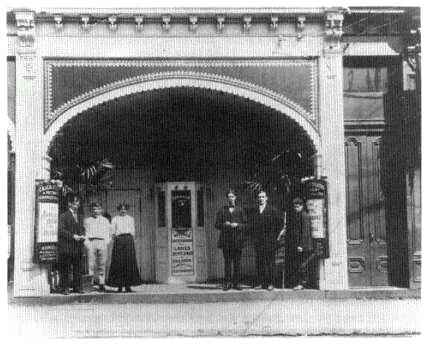

In September 1881, however, work began on Connellsville's first commercial theater, the Newmyer Opera House, a source of civic pride, "as finely furnished as any in the country."[35] According to one local reporter, "The stage is fitted up with a thousand dollar piano, a five-piece parlor set and Brussels carpet. The drop curtain is one of the prettiest we have seen anywhere, and is supplemented with abundant scenery of various kinds."[36] After opening with a performance of Camille , the opera house was frequented by many traveling companies.

Edwin Porter later recalled: "I worked around a local theater of which my brother was manager; acted in the capacity of ticket taker, usher, etc."[37] While the Newmeyer did have a manager named Porter during the 1883-84 and 1884-85 seasons, this was Byron Porter, at most a distant relative.[38] His small orchestra provided visiting theatrical companies with music. It also gave concerts, performing pieces that were arranged, and in at least one instance composed, by Byron Porter himself.[39] Called "the leading artist in this section of the state,"[40] Byron Porter was apparently an important figure in Ed Porter's early life. The two Porter families were closely associated; and, as manager of the opera house, Byron Porter had to maintain links with the town's main undertaker and furniture store in case he needed additional seating. Young Edward was an apparent beneficiary. Byron Porter was also the town's first photographer and ran a photographic gallery and art store. He may have taught Edward the rudiments of photography, an invaluable skill for his subsequent career.[41]

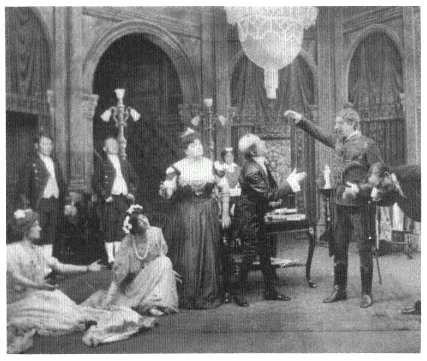

The Newmyer Opera House exposed Porter to a wide range of theatrical experiences. The ever-popular Uncle Tom's Cabin , which enjoyed a unique place in American cultural life, was performed there many times during Porter's Connellsville residence. In later years he was said to have acted out the story as a child, assuming the role of slave owner Simon Legree.[42] Other companies gave minstrel shows, melodramas, various works by Gilbert and Sullivan, travesties like the seriocomic Medea , Irish plays like Hibernica and Shamus O'Brien , and even a few tragedies. Performances included Daniel Boone; or, On the Trail (a local favorite), Peck's Bad Boy, The Count of Monte Cristo (minus James O'Neill), and She , adapted from Rider Haggard's book and produced by William Brady. The opera house was also used by the Kickapoo Indians, a medicine show; for wrestling matches; and to host a visit by John L. Sullivan, the world's boxing champion.[43] This eclecticism of subject matter would find continuity in much of Porter's own filmmaking career, if only as a result of similar commercial pressures. Certain of his pictures may have also been informed by Porter's early experience in the opera house—for instance, Uncle Tom's Cabin (1903), the Irish drama Kathleen Mavourneen (1906), Daniel Boone (1906), and She (1908). His later conception of cinema as filmed theater must have owed something to this as well.

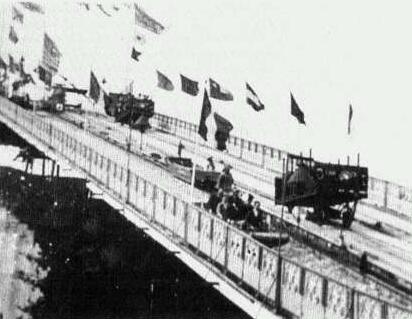

As a successful filmmaker, Edwin Porter recalled other jobs that acquainted him with the mechanical end of the theatrical business. "Later my brother was

'advance' for Washburn and Huntington's circus. I was on the bill car. In that way I came to have a general idea of the circus business. I also traveled with him a part of the season in comic opera."[44] Although these experiences are impossible to verify, they were not unusual for the period; Vaudeville magnate Benjamin Franklin Keith entered the world of commercial amusements after visiting the circus at seventeen.[45] Edward Franklin Albee and Frederick F. Proctor, both prominent vaudeville entrepreneurs, also had early circus experiences.[46] Circuses were the major form of commercial summer amusement in many sections of the United States and frequently came to Connellsville while Porter was growing up. A visit from Barnum's Circus was an important event on the year's calendar, with 20,000 people seeing the main attraction in one day. In 1888 Forepaugh's Wild West Show stopped off and reenacted the holdup of the Deadwood Stage and "Custer's last rally."[47]

Porter also claimed to have been an exhibition skater. Roller-skating became a craze for the first time in the mid 1880s. During the winter of 1884-85 Connellsville had two indoor skating rinks. At their height, the rinks offered recreational skating in which the sexes mingled in casual social contact. Rink managers drew customers by presenting exhibition skaters, bicycle acts, and variety companies. They organized competitions and sponsored "a neck-tie and apron social."[48] Only a few out-of-town performers are mentioned in press clippings, but Porter could have easily been a local demonstrator. Porter thus associated himself with the three major forms of popular culture then making their appearance in Connellsville: the opera house, the circus, and the skating rink.

The emergence of commercial, popular culture in Connellsville during the 1880s produced a cultural split within the town's middle class. The rise of various amusement forms challenged what Alan Trachtenberg has called a virtually official middle-class image of America that was "a deliberate alternative to two extremes, the lavish and conspicuous squandering of wealth among the very rich, and the squalor of the very poor."[49] This Protestant culture sought to enrich people's lives through self-cultivation and self-education. It was centered in the churches, which provided an array of lectures and other educational opportunities. Among these were several examples of pre-cinematic screen entertainment. The lantern shows Paradise Lost, The Customs and Times of Washington , and Sights and Scenes in Europe were given at Methodist, Episcopal, and Lutheran churches.[50] A panorama showing painted scenes of America and Europe was exhibited by Presbyterian and Baptist denominations.[51] In Connellsville, as in most communities outside the metropolitan centers, these two entertainment forms continued to be aligned with religious institutions seeking to educate, inspire, and entertain their mostly middle-class congregations.

The opera house, the circus, and the skating rink did not attempt to educate their patrons; they sought instead to address their desires. They drew middle-

class people away from evening lectures. Trying to revive these older forms of community entertainment, some lectures were moved to Newmyer Opera House; attendance, however, did not improve.[52] In frustration ministers and conservative newspapers denounced the skating rinks, but without success. "The louder the denunciations, the more popular the rinks grew."[53] This reaction against secular, comparatively informal forms of amusement was intensified with the appearance of the Salvation Army in 1886. The pro-amusement Keystone Courier reported its arrival with derisive headlines, calling the group "a case of misdirected energy."[54] The Young Men's Christian Association, which appeared in Connellsville in late 1884, was a more moderate attempt to maintain or expand the church's position in an increasingly secularized cultural life.[55] In the confrontation between church-oriented, moralizing culture and popular commercial culture, Porter sided with the latter.