The Great Train Robbery

In late October, Porter began working with a young actor, Max Aronson. Earlier that month, the thespian had toured with Mary Emerson's road company of His Majesty and the Maid .[57] The engagement did not work out, and he returned to New York in need of employment. After changing his name to George M. Anderson, Aronson found work at the Edison studio, thinking up gags (Buster's Joke on Papa , shot October 23d) and appearing in pictures (What Happened in the Tunnel , photographed on October 30th and 31st). Porter continued to collaborate with Anderson on numerous subjects over the next several months, including The Great Train Robbery .

The Great Train Robbery was photographed at Edison's New York studio and in New Jersey at Essex County Park (the bandits cross a stream at Thistle Mill Ford in the South Mountain Reservation) and along the Lackawanna railway during November 1903.[58] Justus D. Barnes played the head bandit; Anderson the slain passenger, the tenderfoot dancing to gunshots, and one of the robbers; and Walter Cameron the sheriff. Many of the extras were Edison em-

ployees. Most of the Kinetograph Department's staff contributed to the picture: J. Blair Smith was one of the photographers and Anderson may have assisted with the direction.[59]

The film was first announced to the public in early November 1903 as a "highly sensationalized Headliner" that would be ready for distribution early that month.[60] Since the Edison Manufacturing Company urged exhibitors to order in advance and the film was not ready until early December, the delay probably explains why the Kinetograph Department submitted a rough cut of the film for copyright purposes. It avoided distribution snags once the release prints were available. The paper print version of the film, copyrighted by the Library of Congress, is longer than the final release print by about fifteen feet. Over the years, surviving copies of the film have been duped and offered for sale. Although a few have suffered extensive alteration, most have their integrity fundamentally intact. One of the most interesting versions was hand tinted.[61]

The Great Train Robbery had its debut at Huber's Museum, where Waters' Kinetograph Company had an exhibition contract. The following week it was shown at eleven theaters in and around New York City—including the Eden Musee.[62] Its commercial success was unprecedented and so remarkable that contemporary critics still tend to account for the picture's historical significance largely in terms of its commercial success and its impact on future fictional narratives. Kenneth Macgowan attributes this success to the fact that The Great Train Robbery was "the first important western."[63] William Everson and George Fenin find it important because "it was the first dramatically creative American film, which was also to set the pattern—of crime, pursuit and retribution—for the Western film as a genre."[64] Robert Sklar, viewing the film in broader terms, accounts for much of the film's lasting popularity. He points out that Porter was "the first to unite motion picture spectacle with myth and stories about America that were shared by people throughout the world."[65] Little more has been said about Porter's representational strategies since Lewis Jacobs praised the headliner for its "excellent editing."[66] Noël Burch, André Gaudreault, and David Levy are among the few who have discussed the film's cinematic strategies with any historical specificity; their useful analyses, however, can be pushed further.[67]The Great Train Robbery is a remarkable film not simply because it was commercially successful or incorporated American myths into the repertoire of screen entertainment, but because it presents so many trends, genres, and strategies fundamental to cinematic practice at that time.

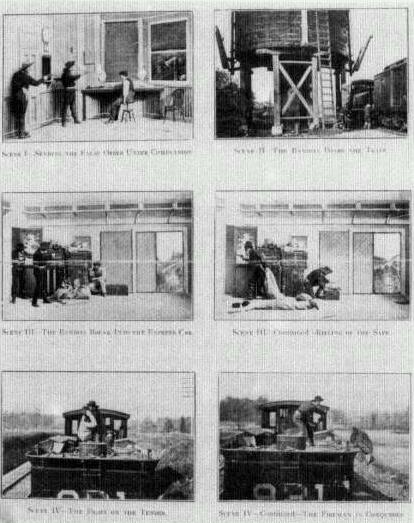

Porter's film meticulously documents a process, applying what Neil Harris calls "an operational aesthetic" to the depiction of a crime.[68] With unusual detail, it traces the exact steps of a train robbery and the means by which the bandits are tracked down and killed. The film's narrative structure, as Gaudreault notes, utilizes temporal repetition within an overall narrative progression. The robbery of the mail car (scene 3) and the fight on the tender (scene

4) occur simultaneously according to the catalog description, even though they are shown successively. This returning to an earlier moment in time to pick up another aspect of the narrative recurs again in a more extreme form, as the telegraph operator regains consciousness and alerts the posse, which departs in pursuit of the bandits. These two scenes (10 and 11) trace a second line of action, which apparently unfolds concurrently with the robbery and getaway (scenes 2 through 9), although Porter's temporal construction remains imprecise and open to interpretation by the showman's spiel or by audiences through their subjective understanding. These two separate lines of action are reunited within a brief chase scene (shot 12) and yield a resolution in the final shoot-out (shot 13).

The issue of narrative clarity and efficiency is raised by The Great Train Robbery . At one point, three separate actions are shown that occur more or less

simultaneously in scenes 3, 4, and 10. How were audiences, even those that understood the use of temporal repetition and overlap in narrative cinema, to know that scenes 3 and 4 happened simultaneously, but not scenes 1 and 2? How were they to determine the relationships between shots 1-9 and 10-11 until they had seen shot 12? There are no intertitles, and much depended on audience familiarity with other forms of popular culture where the same basic story was articulated. Scott Marble's play The Great Train Robbery , Wild West shows, and newspaper accounts of train holdups were more than sources of inspiration: they facilitated audience understanding by providing a necessary frame of reference. While The Great Train Robbery demonstrated that the screen could tell an elaborate, gripping story, it also defined the limits of a certain kind of narrative construction.

The common belief that The Great Train Robbery was an isolated breakthrough is inaccurate. While Porter was making his now famous film, Biograph produced The Escaped Lunatic , a hit comedy in which a group of wardens chase an inmate who has escaped from a mental institution.[69] On the very day that Thomas Edison copyrighted his celebrated picture, Biograph copyrighted a 290-foot subject made by British Gaumont, Runaway Match , involving an elaborate car chase between an eloping couple and the girl's parents. Eleven days later the film was offered for sale as An Elopement a la Mode .[70]

A Daring Daylight Burglary , which the Edison Company had duped and marketed in late June, was particularly influential in creating the framework within which Porter produced The Great Train Robbery ,[71] even though American popular culture provided the specific subject matter. Edison's 1901 Stage Coach Hold-up , a film adaptation of Buffalo Bill's "Hold-up of the Deadwood Stage," served as one source. The title and initial idea for the film were suggested, however, by Scott Marble's melodrama. The New York Clipper provides a story synopsis:

A shipment of $50,000 in gold is to be made from the office of the Wells Fargo Express Co. at Kansas City, Mo., and this fact becomes known to a gang of train robbers through their secret agent who is a clerk in the employ of the company. The conspirators, learning the time when the gold is expected to arrive, plan to substitute boxes filled with lead for those which contain the precious metal. The shipment is delayed, and the lead filled boxes are thereby discovered to be dummies. This discovery leads to an innocent man being accused of the crime. Act 2 is laid in Broncho Joe's mountain saloon in Texas, where the train robbers receive accurate information regarding the gold shipment and await its arrival. The train is finally held-up at a lonely mountain station and the car blown open. The last act occurs in the robber's retreat in the Red River cañon. To this place the thieves are traced by United States marshals and troops, and a pitched battle occurs in which Cowboys and Indians also participate.[72]

The play premiered on September 20, 1896, at the Alhambra Theater in Chicago, and soon came to the New York area, where it was well received.[73]

One page of Edison's illustrated catalog for The Great Train Robbery.

The operational aesthetic at work: the film details the robbery of a train step by step.

Periodically revived thereafter, the melodrama played at Manhattan's New Star Theater in February 1902. Porter could have easily seen it on several occasions.

The Great Train Robbery was advertised as a reenactment film "posed and acted in faithful duplication of the genuine 'Hold-ups' made famous by various outlaw bands in the far West."[74] News stories of train holdups, like the ones appearing in September 1903, may have encouraged a more authentic detailing

of events (see document no. 14). Eastern holdups, also evoked in Edison ads, took place in Pennsylvania on the Reading Railroad in late November—after the film was completed. A telegraph operator was murdered and several stations held up by "a desperate gang of outlaws who are believed to have their rendezvous somewhere in the lonely mountain passes along the Shamokin Division."[75] It was hoped that such incidents would make the film of timely interest. The Great Train Robbery continued to be indebted to at least one aspect of the newspapers, the feuilletons in Sunday editions, with their highly romanticized, but supposedly true, stories of contemporary interest.

DOCUMENT NO . 14 |

KILLS HIGHWAYMAN |

Express Messenger Prevents Robbery-Bullet Wounds Engineer. |

Portland, Ore. Sept. 24.-The Atlantic Express on the Oregon Railroad and Navigation line, which left here at 8:15 o'clock last night, was held up by four masked men an hour later near Corbett station, twenty-one miles east of this city. One of the robbers was shot and killed by "Fred" Kerner, the express messenger. "Ollie" Barrett, the engineer, was seriously wounded by the same bullet. The robbers fled after the shooting, without securing any booty. Two of the highwaymen boarded the train at Troutdale, eighteen miles east of here, and crawled over the tender and to the engine, where they made the engineer stop near Corbett station. |

When the train stopped two more men appeared. Two of the robbers compelled the engineer to get out of the cab and accompany them to the express car, while the others watched the fireman. The men carried several sticks of dynamite, and, when they came to the baggage car, thinking it was the express car, threw a stick at the door. Kerner heard the explosion, and immediately got to work with his rifle. The first bullet pierced the heart of one of the robbers and went through his body, entering the left breast of Barrett, who was just behind. Barrett's wound is above the heart, and is not necessarily fatal. |

After the shooting the other robbers fled, without securing any booty, and it is supposed that they took to a boat, as the point where the hold-up occurred is on the Columbia River. |

The robbers ordered Barrett to walk in front while approaching the baggage car, but he jumped behind just before the express messenger fired. The body of the dead robber was left behind on the track, and the wounded engineer was brought to this city. Sheriff Story and four deputy sheriffs went on a special train to the scene of the robbery, where one of the gang of outlaws was found badly wounded from a charge of buckshot |

(Text box continued on next page)

which he received in the hand. He said that his name was James Connors of this city but refused to tell the names of any of the other bandits or the direction in which they went. The Oregon Railroad and Navigation Company offers a reward of $1 000 for the arrest of the highwaymen. |

SOURCE : New York Tribune September 25 1903p. 14. |

As David Levy has pointed out, it was within the genre of reenactment films that Porter exploited procedures that heighten the realism and believability of the image.[76]Execution of Czolgosz and Capture of the Biddle Brothers provided Porter with an approach to filming the robbery, chase, and shoot-out. In Execution of Czolgosz he had intensified the illusion of authenticity by integrating actuality and reenactment, scenery and drama. In The Great Train Robbery he took this a step further, using mattes to introduce exteriors into studio scenes. On location, Porter used his camera as if he were filming a news event over which he had no control. In scenes 2, 7, and 8 the camera is forced to follow action that threatens to move outside the frame. For scene 7 the camera has to move unevenly down and over to the left. Since camera mounts were designed either to pan or tilt, this move is somewhat shaky. This "dirty" image only adds to the film's realism. The notion of a scene being played on an outdoor stage was undermined. Biograph described the desired effect when advertising The Escaped Lunatic : "Fortunately there were a number of . . . cameras situated around the country . . . and this most astonishing episode was completely covered in moving pictures."[77]