3

Edison and the Kinetoscope: 1888-1895

When Porter was eighteen years old and still living in Connellsville, Thomas Edison was contemplating a new invention that would record and play back a series of photographs so as to create the illusion of a moving image. Edison's initial interest was sparked by the photographer Eadweard Muybridge, who presented his zoöpraxiscope in Orange, New Jersey, on February 25, 1888, and stayed on to meet Edison at his laboratory two days later.[1] Muybridge and Edison discussed the possibility of combining the former's projecting machine and the latter's phonograph.[2] "I am experimenting upon an instrument which does for the Eye what the phonograph does for the Ear, which is the recording and reproduction of things in motion, and in such a form as to be both Cheap practical and convenient," Edison wrote in October 1888. "This apparatus I call a Kinetoscope 'Moving View.'"[3] Thinking of a motion picture machine in terms of the phonograph provided a familiar frame of reference for the inventor and those employees working on the project, but the parallels would often prove to be a stumbling block. Edison initially planned to have approximately 42,000 images, each about 1/32 of an inch wide, on a cylinder that was the size of his phonograph records. These would be taken on a continuous spiral with 180 images per turn. An individual spectator could then look at twenty-eight minutes of pictures through a microscope while listening to sound from a phonograph.[4]

By June 1889 twenty-nine-year-old William Kennedy Laurie Dickson, one of Edison's chief experimenters and a reputable photographer in his own right, was formally assigned to the project.[5] He and Charles A. Brown (Dickson's chief assistant for this project) worked in Laboratory Room 5, where they received

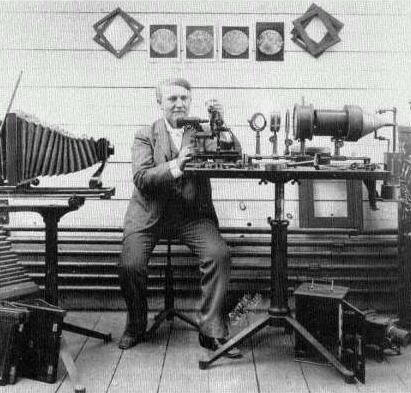

Thomas Edison as photographed by W. K. L. Dickson.

periodic help from Frederick P. Ott, Eugene Lauste, and others. Brown explained their experiments at this stage: "We first took the phonograph and coated a cylinder and put onto it and had a lens taken out of a microscope and rigged onto it, and then they had a coarse feed wheel onto it so as to run slower, and that fed the lens along in front of the coated cylinder; but we made a great many experiments during that time in trying to see how small pictures we could get."[6] Vibrations in the nearby machine shops were felt to contribute to their difficulties. While Edison was away on his European tour in the late summer and early fall of 1889, Dickson arranged for the construction of a special photographic building for the sum of $516.64. It was in this building, during late 1889 or 1890, that Edison's initial idea was realized in modified form with larger cylinders of approximately 4½ inches in diameter. Leaves of photographic film were wrapped around the cylinders and a series of tiny images were taken, spiralling down its length. A few surviving "films" show a man dressed in white against a black background. He faces the camera and makes strongly

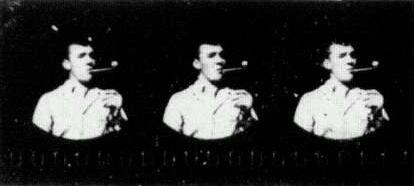

Experimental subject taken by W. K. L. Dickson and William Heise with

the 1891 horizontal-feed camera (larger than life-size). The subject is James

Duncan, a day worker at Edison's laboratory.

delineated gestures in a presentational style. Some of the frames are blurred, and it is evident that the idea encountered many difficulties.

During his European travels, Edison met Etienne Jules Marey and learned of the Frenchman's successful efforts to photograph a continuous series of images on a film strip that moved along intermittently in front of a single camera lens. Shortly after returning to his laboratory, Edison drew up a new motion picture caveat that reflected these conceptual advances. The successful construction of an instrument based on these principles was postponed, however, as Edison and Dickson devoted most of their time to iron ore milling. Work on the kinetograph revived in October 1890, when Dickson was joined by a new assistant named William Heise. They constructed a new camera that used a ¾-inch strip of film. The film was exposed by using a horizontal-feed system rather than the vertical-feed one that would come to characterize modern motion pictures. A single row of small perforations ran along the bottom edge of the band. Finally, on May 20, 1891, Edison was able to unveil a peep-hole viewing machine.[7] Participants in a convention of the National Federation of Women's Clubs were brought to the Edison laboratory, where they saw "the picture of a man. It was a most marvellous picture. It bowed and smiled and waved its hands and took off its hat with the most perfect naturalness and grace. Every motion was perfect."[8] The man was Dickson. Several additional subjects were taken at this time, including a boxing scene, a full-figure view of a juggler, and a close view of a man with a pipe.[9] All were shot against black backgrounds; in the last two, the subjects faced the camera. That June, Dickson and Edison lawyers began to prepare three patent applications for a motion picture camera (the kinetograph) and a peep-hole viewing device (the kinetoscope). Finally submitted on August 24th to the U.S. Patent Office, these applications

initiated a series of legal maneuvers that were to continue for more than twenty years.

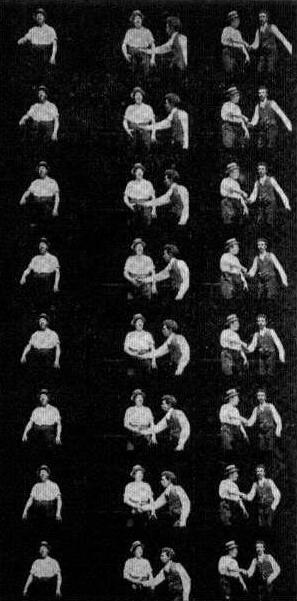

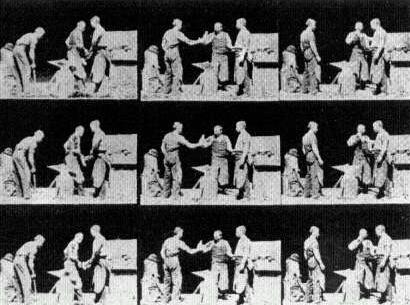

Edison and Dickson developed their vertical-feed, 1½-inch (approximately 35mm) motion picture camera during the summer of 1892. Firm evidence of this appeared in October, when frames of motion picture subjects were published in the Phonogram , a trade journal for the phonograph industry.[10] Two scenes, of men fencing and boxing, owed much to the subject choices and representational methods evident in Muybridge's serial photography. Another begins with William Heise standing alone in the frame. W. K. L. Dickson enters from behind the camera and shakes hands as both men face an imagined audience. This documentation of celebration and authorship marked the successful completion of Edison's search for a worthwhile motion picture system. These films, while not for commercial exhibition, embodied characteristics that would remain important in the years ahead. The isolation of actions and figures against a black background and the subjects' open acknowledgment of the camera retained the presentational elements evident in earlier experiments. Everyone in front of the camera was male, congruent with the homosocial world of the laboratory. In many instances, laboratory personnel acted as subjects. This approach continued for later experimental films, notably Dickson Experimental Sound Film (taken in late 1894 or early 1895). For this, Dickson played the violin into a phonograph funnel while two male employees danced with each other.

Preparations

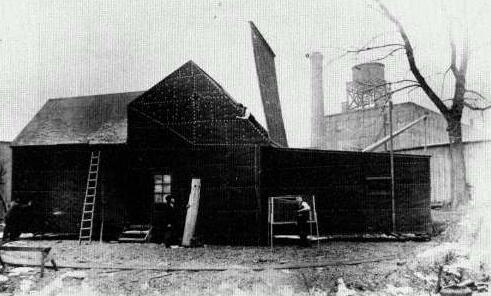

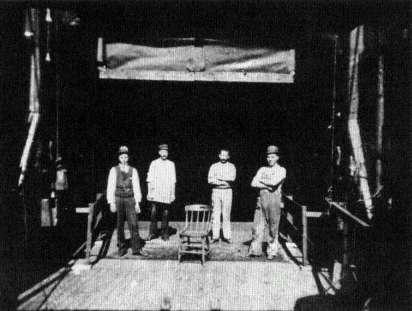

Construction of a motion picture studio began at Edison's West Orange laboratory in December 1892. The inventor and his secretary, Alfred O. Tate, were making commercial arrangements for the invention's exploitation at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago and production facilities were essential. The studio, which became known as the Black Maria, after the black paddy wagons it was said to resemble, was completed the following February at a cost of $637.67.[11] It was approximately fifty feet long and thirteen feet wide. A stage was at one end "entirely lined with black tar paper, giving the effect of a dead black tunnel behind the subject being photographed."[12] The studio rotated on a graphite center and tracks so that sunlight could fall directly on the performers.

The shift from experimental to commercial filmmaking involved many continuities. Blacksmith Scene , one of the first motion pictures shot in the new studio, illustrates this. The earliest Edison film to have a commercial life, it was taken before May 1893 by Dickson and Heise. As this suggests, the people immediately responsible for inventing the hardware remained in charge of the kinetograph during this new phase. Characteristically, Edison declined to shift personnel when moving from the phase of invention to that of commercial exploitation. Moreover, the collaborative approach to invention (i.e., Edison-

A Hand-Shake (1892). Dickson and Heise

congratulate each other on their invention.

The Black Maria studio (March 1894).

Dickson and Dickson-Heise) was continued as part of the production process. Other continuities are likewise striking: the black backgrounds and the frontal organizations of the mise-en-scène.

Blacksmith Scene depicted a blacksmith and his two helpers hammering an iron forging on the anvil, stopping to pass around a bottle of beer, and then resuming their labors. Although it reworked a subject previously photographed by Muybridge, the activity had become much more elaborate. Edison personnel constructed a fictional workspace within their workspace. Charles Kayser appears to be playing the role of the blacksmith, and the two others are almost certainly Edison employees. The world of the laboratory was transfigured in the blacksmith's shop. A conscious element of play was undoubtedly operating, for the crude smithy contrasted markedly with Edison's sophisticated machine shop. Yet there seem to have been important parallels. The fictionalized workspace has someone "in charge," the head blacksmith; but lines of authority are attenuated by egalitarianism and informality. Work, pleasure, and socializing are interwoven. In terms of American work culture, this scene already presents a nostalgic view, for, as Roy Rosenzweig has remarked, by the late nineteenth century, work and socializing were increasingly separated, with workplace drinking considered part of a bygone era.[13] Nevertheless, this film conveys the interpenetration of work and leisure characteristic of the Edison laboratory environment. The very making of the film seems to have been such an effort. Employees put aside serious undertakings to assume the roles of blacksmiths. If they were expected to work long hours and produce results, discipline was lax

Blacksmith Scene (1893). Work and pleasure are intermixed.

and responsibilities were often loosely defined. The informal lines of authority are also evident in the way that W. K. L. Dickson, the man most responsible for the film, copyrighted the subject even though the films and materials were owned by Edison.[14] Edison was not seeking to conduct an efficient workplace but to establish an environment where creativity could flourish.

Blacksmith Scene served as the centerpiece for the first public demonstration of Edison's new l½-inch system, at the Brooklyn Institute on May 9, 1893 (see document no. 1). Conducted by George M. Hopkins, president of the institute's Department of Physics, this presentation was remarkable in that it took the form of an illustrated lecture. To explain the principles on which the kinetograph and kinetoscope were based, Hopkins used a magic lantern to project a series of images from a choreutoscope (created in 1866), which created a dancing skeleton. Projected moving images from an instrument similar to Muybridge's zoöpraxiscope were also shown. Edison and Dickson's accomplishments were carefully situated in the general context of efforts being made in "chronophotography." The superior results of their efforts were carefully noted.

Selected frames of Blacksmith Scene were then projected onto the screen one frame at a time for inspection by the audience of approximately four hundred scientific people. Hopkins emphasized that the kinetoscope in its complete form was a machine for projecting images on the screen with recorded synchronous

The interior stage area of the Black Maria. Some

of the personnel appeared in Blacksmith Scene.

sound. Journal formats aside, the first public presentation of modern motion picture frames was done on this screen. Only at the evening's conclusion did those present file by a peep-hole kinetoscope and peer into the machine. With each peep taking half a minute, the last part of the evening lasted more than three hours.

DOCUMENT NO . 1 |

First Public Exhibition of Edison's Kinetograph. |

At the regular monthly meeting of the Department of Physics of the Brooklyn Institute, May 9, the members were enabled, through the courtesy of Mr. Edison, to examine the new instrument known as the kinetograph [sic , i.e., kinetoscope]. The instrument in its complete form consists of an optical lantern, a mechanical device by which a moving image is projected on the screen simultaneously with the production by a phonograph of the words or song which accompany the movements pictured. For example, the photograph of a prima donna would be shown on the screen, with the movements of the lips, the head, and the body, to- |

(Text box continued on next page)

gether with the changes of facial expression, while the phonograph would produce the song; but to arrange this apparatus for exhibition for a single evening was impracticable. Therefore, a small instrument designed for individual observation, and which simply shows the movements without the accompanying words, was shown to the members and their friends who were present. |

Mr. George M. Hopkins, president of the department, before proceeding to the exhibition of the instrument offered a brief explanation, in which he said: "This apparatus is the refinement of Plateau's phenakistoscope or the zootrope, and like everything Mr. Edison undertakes, it is carried to great perfection. The principle can be readily understood by anyone who has ever examined the instrument I have mentioned. Persistence of vision is depended upon to blend the successive images into one continuous ever-changing photographic picture. |

"In addition to Plateau's experiments, I might refer to the work accomplished by Muybridge and Anschuetz, who very successfully photographed animals in motion, and to Demeny, who produced an instrument called the phonoscope, which gave the facial expression while words were being spoken, so that deaf and dumb people could readily understand. But these instruments, having but twenty-five or thirty pictures for each subject, could not be made to blend the different movements sufficiently to make the image appear like a continuous photograph of moving things; the change from one picture to the next was abrupt and not realistic. In Mr. Edison's machine far more perfect results are secured. The fundamental feature in his experiments is the camera, by means of which the pictures are taken. This camera starts, moves, and stops the sensitive strip which receives the photographic image forty-six times a second, and the exposure of the plate takes place in one-eighth [sic ] of this time or in about one fifty-seventh of a second. The lens for producing these pictures was made to order at an enormous expense, and every detail at this end of the experiment was carefully looked after. There are 700 impressions on each strip, and when these pictures are shown in succession in the kinetograph the light is intercepted 700 times during one revolution of the strip. The duration of each image is one-ninety-second of a second, and the entire strip passes through the instrument in about thirty seconds. In the kinetograph each image dwells upon the retina until it is replaced by the succeeding one, and the difference between any picture and the succeeding one or preceding one is so slight as to render it impossible to observe the intermittent character of the picture. To explain in a very imperfect way the manner in which the photographs are produced, I will present the familiar dancing skeleton on the screen. You will notice that the image appears to be continuous, but the eye fails to notice the cutting |

(Text box continued on next page)

off of the light, and the image simply appears to change its position without being at all intermittent; but when the instrument is turned slowly, you will notice that the period of eclipse is much longer than the period of illumination. The photographs on the kinetograph strip were taken in some such way as this. I will exhibit an ordinary zootrope adapted to the lantern, which shows the principle of the kinetograph. In this instrument, a disk having a radial slit is revolved rapidly in front of a disk bearing a series of images in different positions, which are arranged radially. The relative speeds of these disks are such that when they are revolved in the lantern the radial slit causes the images to be seen in regular succession, so that they replace each other and appear to really be in motion; but this instrument, as compared with the kinetograph, is a very crude affair." |

After projecting upon the screen a few sections of the kinetograph strip, the audience—which consisted of more than 400 scientific people— was allowed to pass by the instrument, each person taking a view of the moving picture, which averaged for each person about half a minute. The picture represented a blacksmith and two helpers forging a piece of iron. Before beginning the job a bottle was passed from one to the other, each imbibing his portion. The blacksmith then removed his white hot iron from the forge with a pair of tongs and gave directions to his helpers with the small hand hammer, when they immediately began to pound the hot iron while the sparks flew in all directions, the blacksmith at the same time making intermediate strokes with his hand hammer. At a signal from the smith, the helpers put down their sledge hammers, when the iron was returned to the forge and another piece substituted for it, and the operation was repeated. |

In the picture exhibited in the kinetograph, every movement appeared perfectly smooth and natural, without any of the jerkiness seen in instruments of the zootrope type which have heretofore been exhibited. |

The machine in this case was not accompanied by the phonograph, but nevertheless the exhibition was one of great interest. The kinetograph in this form is designed as a "nickel in the slot" machine, and a number of them have been made for use at the Columbian Exhibition at Chicago. |

SOURCE : Scientific American , May 20, 1893, p. 310. |

The Black Maria was rarely used for production during 1893, as the refinement of Edison's motion picture system and the manufacture of kinetoscopes experienced delays. W. K. L. Dickson suffered from nervous exhaustion and was absent from the laboratory between early February and late April 1893. Although this accounts for some of the slowdown, the recession of 1893 may have further impeded this project, as Edison devoted his hard-pressed finances and time to iron ore milling. A new model kinetoscope for films taken with the

vertical-feed kinetograph was probably not available until shortly before the Brooklyn Institute demonstration in May. A contract for the manufacture of twenty-five machines based on this prototype was only drawn in late June. Gordon Hendricks indicates that it was given to an Edison employee who had difficulty staying sober. As a result, the machines were not completed until March 1894. Only the prototype was available for exhibition at the Chicago exposition, and this proved too valuable to send.[15]

Initial Film Production

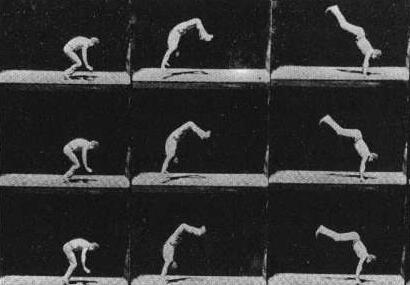

The imminent completion of the kinetoscopes spurred the Edison group into serious film production. Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze (© 9 January 1894) was a short film made for publicity purposes during the first week of January 1894.[16] By the beginning of March, Dickson and assistant William Heise had shot The Barbershop and Amateur Gymnast , both full-length subjects. As with most films made during the coming year, these were slightly less than fifty feet long, shot at approximately forty frames per second, and lasted less than twenty seconds. Like Blacksmith Scene, The Barbershop depicts a homosocial environment where easy comradery is routine. A customer receives a "lightning shave" for five cents—the cost of seeing the film. Since the shave and the viewing of the film take the same amount of time, the subject would seem to gently rib the film spectator, who has been quickly separated from his money. Yet the depiction of a complete shaving cycle highlights the work process (the barber's) and treats the barbershop as both a workplace and a place of leisure.

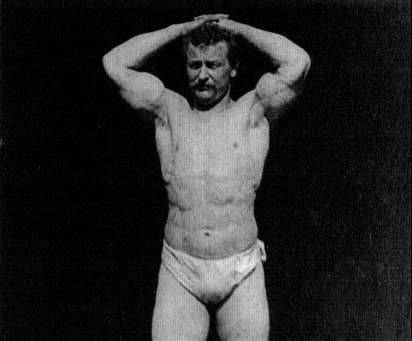

Amateur Gymnast shows a young man performing a somersault: it was probably one of several films taken of members of the Newark Turnverein, a nearby athletic club. Others show two men on parallel bars and a brief boxing match.[17] These may have been rehearsals for the kinetograph's first famous visitor, the strongman Eugene Sandow. On March 6th Sandow came to the Edison laboratory accompanied by the management of Koster & Bial's, the music hall where he was then performing. For the kinetograph, Sandow stripped to a loincloth and assumed an array of positions that showed off his muscular physique. In cinematography as in photography, Dickson had a well-trained eye. His camera framed Sandow just above the knees. Against the black background, the strongman's physique captured the complete attention of his audience.

Making Sandow and other films for this new type of commercial amusement fit easily into the laboratory environment. Although Sandow demanded a $250 fee to pose in the Black Maria unless he could meet Wizard Edison himself, this stipulation was probably unnecessary. Edison, an aficionado of variety entertainment, was delighted to meet the performer. Using a still camera next to the kinetograph, Dickson took several photographs: one caught "Mr. Edison feeling Sandow's muscles with a curiously comical expression on his face."[18] To entertain the inventor, the strongman playfully tossed one of his entourage out the

Amateur Gymnast (1894).

window. The kinetograph added a dash of levity to the laboratory milieu, burdened by discouraging, money-losing efforts in other areas.

The films taken through early March were of men, by men, and principally for men. But this quickly changed. During the second week of that month, the dancer Carmencita pirouetted for the kinetograph—her dress twirling and rising as high as her knees. As the New York Times proclaimed, "the vigor, dash, and sinuous movements of Carmencita herself, having long since defied imitation or improvement, were still indefinable and unique."[19] Unfortunately, the few surviving frames of Carmencita fail even to hint at the reasons for her reputation. Her rise to stardom occurred under Koster & Bial management at their old music hall on Twenty-third Street. There she attracted unprecedented accolades from critics at all the city newspapers. Whatever her actual abilities, like Edison, she was a larger-than-life creation of the mass circulation dailies.[20] She was soon followed by the female contortionist Mme. Ena Bertoldi, then appearing at Koster & Bial's. Both subjects were meant to appeal to male voyeurs who would soon be peeping into Edison's latest novelty. They were films of women, by men and primarily for men. Sandow, Carmencita, and Bertoldi—all headline attractions—were the first of many variety and vaudeville performers to visit the Black Maria over the ensuing year. The most frequent visitor proved to be Carmencita's chief rival, Annabelle Whitford, who performed her Serpentine,

Eugene Sandow.

Sun, and Butterfly dances on numerous occasions between 1894 and 1897. The billowing gauze of her attire was not only sexually evocative but encouraged hand-coloring effects that transcended a strictly masculine appeal. (Hand-coloring work was usually contracted out to the wives of Edison employees, notably the wife of Edmund Kuhn.) However, a large array of dancers came to perform their specialty, including Ruth Dennis (later Ruth St. Denis), who was promoted as "the Champion High Kicker of the World."[21]

These early films functioned within the homosocial amusement world. Cock Fight , shot in early March, was an extremely popular subject, for which new negatives would often have to be made. Filmed as a close view, the intimate depiction of this brutal sport was enhanced by the roosters' rapid movements and flying feathers. Its success generated similar types of subjects.

Through a New York professional rat catcher, Mr. Dickson secured a large cage full of dock rats and he has had at the laboratory for some time two pretty little full-brooded rat terriers. It was an extremely difficult task to arrange the ring, which on account of the limitations of the kinetograph could be only four feet square. The first

Carmencita.

contest was with six rats turned loose in the pit at once, and in fifty-two and one-half seconds all had been killed by one of the terriers. A second and a third trial were made with equally good results.[22]

Rat Catcher , the result of this undertaking, was ultimately considered "not good, the rats being too small."[23]

Additional vignettes of masculine daily life also continued to be made. By early April, Dickson had shot Horse Shoeing , a simple variation of Blacksmith Scene . This highly specialized "genre" also included A Bar Room Scene , taken later that spring. Another male-dominated space is depicted, although the emphasis has now clearly shifted toward a distinct leisure realm—from passing the beer bottle in a work context to the saloon. In fact, such all-male environments would frequently support nickel-in-the-slot kinetoscopes in the years ahead. Yet for the first time homosocial space is viewed somewhat critically. Socializing takes the form of a political argument that ends in a fight and requires police intervention. This less than flattering depiction of a saloon suggests a disturbance in the choice and depiction of subjects, a desire to meet the demands (real or imagined) of actual spectators.

The commercial debut of the kinetoscope occurred in mid April with the opening of the first kinetoscope parlor in midtown Manhattan. With a peek costing 5¢ and most patrons expected to see a series of five scenes, viewers had to have disposable income. Most were middle class. At its fashionable location, the kinetoscope drew female as well as male patrons. The masculine appeal needed to be tempered, if not effaced. Three films used for this opening were appropriately desexualized: Highland Dance , showing "A 'Lad' and a 'Lassie' in

A Bar Room Scene.

full costume,"[24]Organ Grinder , and Trained Bears . "The bears were divided between surly discontent and a comfortable desire to follow the bent of their own inclinations," Dickson later reported. "It was only after much persuasion that they could be induced to subserve the interests of science."[25] Made to perform elaborate tricks, the animals evidenced man's mastery of nature while still holding out the potential for violence. Correspondingly, Organ Grinder offered a reassuring picture of a happy, harmless Italian street musician, although the perceived threat of the Italian immigrant could not be totally eliminated. Other films made by early summer—for example, The Boxing Cats, The Wrestling Dog , and Glenroy Brothers (a comic boxing routine)—reversed this tension, displaying physical violence induced in the most domesticated of subjects.[26] These subjects parodied and softened the sporting world's manly preoccupations without in any way criticizing them.

These "non-offensive" subjects not only added to the diversity of available images but became essential when the more provocative selections encountered opposition. That summer, for instance, dancing girl subjects were censored by moralistic officials in Asbury Park, New Jersey. Told to close shop or use more

The first kinetoscope parlor at 1155 Broadway, New York City.

acceptable "views," the local exhibitor acquired a print of The Boxing Cats .[27] Such comparatively tame views, however, were not the most popular. The kinetoscope gave women a more enticing opportunity: to glimpse the half-hidden male-oriented world of cock fights and risqué women from which they were ordinarily excluded. It encouraged a distinctly feminine voyeurism (in some instances complicated by a narcissistic identification with the women on display), a counterpoint to that motivated by masculine desire. Yet despite the various possible subject positions, every film drew from the world of popular amusement. Sex or violence was at the core of almost every image.

Exploitation of the Kinetoscope

Edison shifted the manufacture and sale of kinetoscopes and films from his laboratory accounts to the Edison Manufacturing Company, which he completely owned, on April 1, 1894. Expenses incurred to that date—for the development of his motion picture system, the building of a photographic building and the Black Maria, the manufacture of twenty-five kinetoscopes, and the taking of various films—totaled $24,118.[28] Henceforth and for the next eighteen years, the Kinetograph Department at the Edison Company (as it was commonly called) was responsible for the inventor's motion picture business. As this new enterprise was starting up, Thomas Edison hired William Gilmore as vice-president and general manager of this and other Edison companies. Gilmore also commenced April 1st, replacing Tate as the Wizard's business chief.

Edison relied on three different groups to market kinetoscopes and films. The first and most prominent was a consortium that included Edison's former sec-

retary and business manager Alfred O. Tate, phonograph executives Thomas Lombard and Erastus Benson, Norman C. Raft, Frank R. Gammon, and Andrew Holland.[29] Through Tate, they had a long-standing order for the first twenty-five kinetoscopes. As soon as these were completed, ten machines were immediately installed at 1155 Broadway, near Herald Square in New York City, where the kinetoscope had its commercial debut on April 14th. A Chicago kinetoscope parlor, using another ten machines, opened in mid May, while the remaining five had a San Francisco premiere at Peter Bacigalupi's phonograph parlor on June 1st.[30] During one thirteen-day period in late June and early July, the San Francisco parlor brought in $961.20 against $249.60 in expenses (including the month's rent of $175).[31] Similar openings followed in other American cities, with consortium members either exhibiting in lucrative territories or making special arrangements with businesses like the Columbia Phonograph Company, which exhibited the machines in Atlantic City and Asbury Park, New Jersey, and later in Washington, D.C. In August the Holland Brothers opened a kinetoscope parlor in Boston and hired James H. White to assist them. White was soon helping them fit up new arcades with the nickel-in-the-slot machines. Among other undertakings, White and fellow employee Charles H. Webster "installed a plant of kinetoscopes in the Flower Show at the Grand Central Palace, New York City."[32] After this four-week November show, the duo bought the machines, and for the next ten months they traveled to different cities exhibiting films.

Edison initially sold kinetoscopes and films on a first-come, first-served basis.[33] Customers included Thomas L. Tally, then based in Waco, Texas, and William Gilmore's brother-in-law, William H. Markgraf. The disorganization that resulted soon forced Edison to rethink this laissez-faire marketing approach. In mid August, he assigned exclusive responsibility for selling regular kinetoscopes within the United States and Canada to the original consortium with Norman Raft and Frank Gammon acting as its principal agents. Through the newly formed Kinetoscope Company they agreed to purchase approximately ten kinetoscopes a week from Edison for $200 a machine. These machines were in turn sold for as much as $350, with discounts of $25 per machine when several machines were purchased. (Sales to consortium members, however, remained at $200 or $225 per kinetoscope.) This contractual agreement could continue in effect for as much as three years.[34]

From its early contacts with customers, the Edison Company developed relations with two other groups that subsequently assumed major roles in marketing its machines. One began its activities in May when Otway Latham, a manager for the Tilden Company, a pharmaceutical firm, ordered a group of kinetoscopes. Joined by his brother Gray Latham, his father Woodville Latham, and Enoch Rector, a fellow Tilden employee, Otway arranged with Edison to show films of prize fights by expanding the kinetoscope's capacity to 150 feet

and reducing the camera and projection speed to 30 frames per second. The increased running time of slightly more than a minute enabled them to show abbreviated rounds. Their enterprise, which eventually became the Kinetoscope Exhibition Company, commenced its exhibition activities in late August.[35] Franck Z. Maguire and Joseph D. Baucus, heading the other group, made their first purchase in mid July.[36] By September they had incorporated the Continental Commerce Company and acquired the exclusive rights to sell and exhibit the kinetoscope overseas—so long as they worked the territory to Edison's

Table 1 . | ||||

(Rounded off to the nearest dollar) | ||||

Hollands/ | Lathams Kinetoscope Exhibition Co. | Maguire & Baucus Continental Commerce Co. | ||

May 1894 | 2,528 | 1,000 | 0 | |

June | 156 | 0 | 0 | |

July | 2,978 | 0 | 1,275 | |

Aug. | 1,215 | 1,166 | 2,853 | |

Sept. | 5,784 | 1,724 | 9,397 | |

Oct. | 5,565 | 2,369 | 2,678 | |

Nov. | 11,288 | 1,000 | 11,532 | |

Dec. | 9,000 | 2,134 | 12,760 | |

Jan. 1895 | 17,010 | 2,858 | 17,186 | |

Feb. | 2,012 | 2,000 | 14,130 | |

total | 57,537 | 14,271 | 71,811 | |

Mar. 1895 | 3,539 | 1,310 | 1,230 | |

Apr. | 809 | 800 | 3,079 | |

May | 5,091 | 212 | 13,551 | |

June | 5,063 | 90 | 5,182 | |

July | 2,000 | 92 | 1,887 | |

Aug. | 1,001 | 0 | 1,757 | |

Sept. | 1,007 | 810 | 725 | |

Oct. | 0 | 992 | 963 | |

Nov. | 1,001 | 66 | 118 | |

Dec. | 1,000 | 152 | 294 | |

Jan. | 0 | 150 | 14 | |

Feb. | 0 | 36 | 64 | |

total | 20,511 | 4,710 | 28,864 | |

satisfaction.[37] They were expected to dispose of thirteen machines a week for six months and eight machines a week thereafter.

For the business term from April 1894 through February 1895, the Edison Manufacturing Company had kinetoscope sales of $149,549, film sales of $25,882, and "kinetoscope sundries" sales of $2,416. With motion picture sales totaling $177,847, the three groups were responsible for at least $143,620 or approximately 80 percent of Edison's film-related activities during this period.[38] Corresponding profits totaled $85,338. Although their sales were substantial for the next few months, the companies' purchases slumped badly during the summer of 1895 and never recovered. Their activities were responsible for almost all of Edison's motion picture sales for the 1895-96 business year, when total profits for Edison's film-related business fell to $4,141.

Edison Company expenses included substantial fees for W. K. L. Dickson and William Heise in recognition of their important contributions to the development of Edison's motion picture inventions. Dickson received at least $3,150 and Heise at least $850 between August 1894 and February 1895. Dickson continued to receive about $100 and Heise about $40 a week until the end of November 1895. These substantial sums may have been in addition to their regular salaries.[39] The cost of film stock was not assumed by the Edison Company until July 1894 and totaled more than $6,000 by March 1, 1895.[40] Raw stock purchases amounted to $8,460 for the following business year, with their size falling during the summer and increasing again during the winter. Almost all stock was purchased from the Blair Camera Company; contrary to received opinion, none of it came from George Eastman's company. After having shouldered the financial burden for taking the early subjects, Edison (perhaps with Gilmore's urging) shifted these costs to the three groups responsible for commercial exploitation. Each financed its own subjects, which it alone could use unless proper arrangements were made among the various groups. Both Raft & Gammon and Maguire & Baucus indicated their ownership by including small signs with their initials—R (Raft & Gammon), MB (Maguire & Baucus), and C (Continental Commerce Company)—within the scenes being photographed.

Continued Film Production

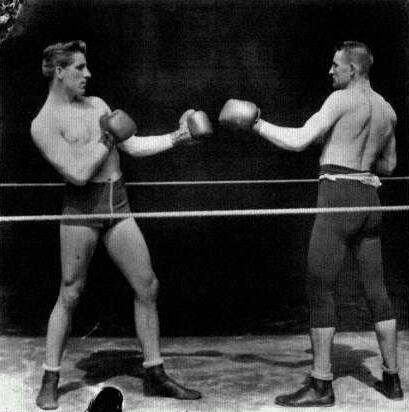

The first subject for the Latham-Rector enterprise was a six-round fight between Michael Leonard and Jack Cushing, filmed by Dickson and Heise in the Black Maria on June 15th.[41] A film of men made by men, The Leonard-Cushing Fight was meant to appeal to the sporting crowd. Again work responsibilities were forgotten as Thomas Edison happily acted as master of ceremonies and supervised the fistic proceedings. His interest was hardly dispassionate, for he found himself mimicking the boxers' thrusts as the fight intensified. When the legality of the fight under New Jersey law was questioned, Edison's role in the

proceedings had to be suppressed. Perhaps this, as much as the time needed for the production of large-capacity kinetoscopes, explains why the Kinetoscope Exhibition Company's storefront arcade on Nassau Street did not open with these films until mid August.

The fruition of Otway Latham's efforts yielded new financing from Samuel J. Tilden, Jr., enabling the group to order seventy-two additional kinetoscopes at $300 a machine.[42] Arrangements were then made for the heavyweight champion James Corbett to fight the New Jersey pugilist Peter Courtney. If he could knock out Courtney in the sixth round, the champion was guaranteed $5,000 against a weekly exhibition fee of $150 (later reduced to $50) for each set of machines on exhibition.[43] On Friday morning, September 7th, four days after Corbett's play Gentleman Jack began a Broadway run, the champion arrived in Orange with his entourage.[44] In the meantime,

Over at the Black Maria, which has been fully described in The Sun , several attendants were busy fixing the kinetograph, so that there might be no slips or mistakes in photographing the impending struggle. The Maria, as the building in which Edison's wonderful machine is located is called, reminded everybody of a huge coffin. It was covered with black tar paper, secured to the woodwork by big metal-topped nails, and was the most dismal-looking affair the sports had ever seen. Inside the walls were painted black, and there wasn't a window of any description, barring a little slide which was directly beside the kinetograph and could be opened or closed at the will of the operator. Half of the roof, however, could be raised or lowered like a drawbridge by means of ropes, pulleys and weights so that the sunlight could strike squarely on the space before the machine.

The ring was 14 feet square. It was roped on two sides, the other two being the heavily padded walls of the building. The floor was planed smooth and covered with rosin. All battles decided in this arena must be fought under a special set of rules. A round lasts a little over one minute, with a rest of a minute and a half to two minutes between the rounds. Consequently, the smallness of the ring and the shortness of the rounds necessitate hot fighting all the time.[45]

At 11 o'clock the prize fighters prepared for the ring, but they were delayed another thirty minutes by a technical problem with the kinetograph.

At 11:45 o'clock everything was ready. The men were first requested to pose in fighting attitudes for an ordinary photograph. Then the chief operator told them to get ready for the fight. John P. Eckhardt of this city was referee and W. A. Brady held the watch. In Corbett's corner were his seconds John McVey and Frank Belcher, with Bud Woodthorpe, bottle holder. In Courtney's corner were John Tracey and Edward Allen, seconds, and Sam Lash, bottle holder. Corbett weighed 195 pounds, he said, and Courtney 190. The men were ordered to shake hands and received instructions as to clinching. Then they went to their corners and waited for the signal to begin the battle. The operators were all ready now, and when the word was given the kinetograph began to buzz.[46]

James Corbett and Peter Courtney pose in the Black Maria before their fight.

Corbett succeeded in knocking out Courtney in the sixth round, and Corbett and Courtney Before the Kinetograph (also known as The Corbett-Courtney Fight ) went on to be a nationwide success. It was shown at Thomas L. Tally's Phonograph and Kinetoscope Parlor at 311 South Spring Street in Los Angeles and in many other large-capacity kinetoscopes across the country. Corbett's contract, however, absorbed much of the profit, and it seems likely that Tilden ultimately lost money on the deal. Moreover, opposition to prize fighting made it difficult to generate additional projects in the months ahead.

After Raft & Gammon and Maguire & Baucus assumed the costs of, and increased responsibility for, making new negatives in September, the same types of subjects continued to be produced. The Kinetoscope Company paid Hornbacker and Murphy to fight a "five round glove contest to a finish" in late September. Each round, however, was limited to fifty feet of film. The

Englehardt Sisters fenced for the kinetograph with both broadswords and foils (Lady Fencers ). Pedro Esquirel and Dionecio Gonzales performed a Mexican knife duel. In January 1895, with variations on the obvious exhausted, Capt. Duncan C. Ross and Lieut. Hartung fought with broadswords on horseback in the five-round Gladiatorial Combat .[47]

Dancers, contortionists, acrobats, and novelty acts also continued to visit the Black Maria from September of 1894 through the following spring. Professor Ivan Tschernoff with his performing dogs, then at Koster & Bial's, appeared in Skirt Dog Dance and Summersault Dog on October 17th. The following day, Toyou Kichi, "the Marvellous and Artistic Japanese Twirler and Juggler," gave a performance for the kinetograph.[48] Robetta and Doreto, who performed their comic routine "Heap Fun Laundry" at the close of Tony Pastor's vaudeville bill for a week beginning on November 26th, also brought their act out to the Edison laboratory (Chinese Laundry Scene ).

With the kinetoscope "one of the recognized sights of the town,"[49] performers and amusement entrepreneurs quickly concluded that moving pictures were good publicity and could help their careers. Prof. Harry Welton's Cat Circus was one of several acts that showed improved bookings subsequent to its appearance in the kinetoscope.[50] The manager for James Hoey's upcoming farce announced a new advertising scheme: "Edison's kinetoscope and phonograph are to be combined in a reproduction of the principal spectacular and vocal feature of the new performance, the instrument to be publicly exhibited in the principal cities weeks prior to the play's appearance."[51] Such a response from the public and the theatrical community enabled kinetograph production to continue drawing from diverse elements of the amusement world.

During the fall, various performers from Buffalo Bill's Wild West show, then at the peak of its popularity, came out to the Edison laboratory.[52] Buffalo Bill, his manager, and a group of Indians traveled from Ambrose park in Brooklyn to appear in a series of films on September 24th. These included Buffalo Bill, Sioux Ghost Dance, Buffalo Dance , and Indian War Council . This last film consisted of "seventeen different persons" and showed Buffalo Bill addressing the Indian warriors.[53] A small group of Mexicans appeared two weeks later to perform their specialty: the knife duel and lasso throwing.[54] On October 16th, rodeo star Lee Martin rode a bucking bronco in a makeshift corral outside the Black Maria (Bucking Broncho ).[55] Finally, on November 1st, Annie Oakley demonstrated her rifle-shooting abilities (Annie Oakley ).[56]

Performers giving specialties in regular New York-based theatrical companies flocked to the West Orange site. On October 6th, Charles Walton and John C. Slavin, from Edward E. Rice's comic opera 1492, executed their comic boxing routine. That same day Lucy Daly's Pickaninnies of The Passing Show tumbled and danced—providing motion pictures with their first images of African Americans. A somewhat later visitor, James Grundy, appearing in The South Before the War , executed a cake walk, buck and wing dance, and breakdown.

Band Drill and Bucking Broncho. The R at the bottom left of the frame stands for Raft & Gammon.

The Grundy films were then marketed as "the best negro subjects yet taken and are amusing and entertaining."[57] Bertha Waring and John W. Wilson, eccentric dancers from the musical burlesque Little Christopher Columbus , and the Jamies from Rob Roy added to this long list.

Two of the most ambitious studio productions were taken in December 1894. Early that month members of the Milk White Flag company presented the camera with five abbreviated scenes from Charles Hoyt's successful song-and-dance farce. The musical satirizes the part-time citizen-soldiers whose "commanderies" served a purely social function. Its many musical and dance numbers were perfect for the kinetoscope. One filmed excerpt, Finale of 1st Act of Hoyt's "Milk White Flag, " had "34 Persons in Costume. The largest number ever shown as one subject in the Kinetoscope."[58] Perhaps the single most ambitious subject of this period was Fire Rescue Scene , made for Raff & Gammon. Filmed inside the Black Maria, the production involved elaborate smoke effects and the assistance of a local fire department. The film can be considered an innovative extension of workplace films like Blacksmith Scene . Certainly, fire-men embodied nineteenth-century manly virtues (courage, strength, etc.), and local fire departments served as centers for many male leisure activities. The homosocial worlds of fire fighting and film production easily converged; they would do so again with much frequency in the years ahead.

Kinetograph activities slowed during the winter months and were then seriously disrupted in April of 1895, when Dickson left Edison's employ. Although this break may have occurred as early as April 2d, it was not made public until late in the month.[59] Dickson's position had become untenable. He had been fighting with Gilmore for control over the motion picture business and for primacy in the inventor's affections. At the same time he was helping two aspiring competitors (the Lathams and the founders of the American Mutoscope Company) develop their own independent motion picture technology. His de-

Fire Rescue Scene.

parture left William Heise responsible for Edison's motion picture business and ended the easy, long-standing collaborative relationship that had produced these films. In the wake of Dickson's departure, Heise proceeded with a handful of additional subjects, perhaps assisted by John Ott. When Barnum and Bailey's Circus stopped in Orange on May 9th, he kinetographed various members of the troupe in the Black Maria before their afternoon performance. Made for the Continental Commerce Company (the circus was soon going to Europe), scenes showed natives of India (Short Stick Dance ), Samoan Islanders (Dance of Rejoicing ), a renowned strongman (Professor Attilla ), and an Egyptian dancer (Princess Ali ).[60]

By mid June, Edison personnel had taken four scenes from Trilby: Death Scene, Dance Scene, Hypnotic Scene , and Trilby Quartette. Trilby , the theatrical adaptation of George du Maurier's novel, opened at the Garden Theatre on April 15th and was proclaimed "an instant and deserved success, which swelled at times to the proportions of a triumph."[61] Even before the opening, however, others were quickly presenting excerpts.[62] Although the actor playing the hypnotist Svengali visited the Edison laboratory in May 1896, it is unlikely that members of the cast did so when the show opened. Moreover, the death scene was buriesqued, suggesting the performance of a renegade group. The Edison-group had ranged freely through various forms of popular amusement to ac-

quire subjects for their productions. Yet they had not moved outside these well-defined boundaries to make actualities or, with a handful of exceptions, their own original scenes. By spring this lack of diversity, as well as the relatively high cost spectators had to pay to peep, led to declining public interest.

Edison's motion picture business faced slackening demand and other difficulties by the spring and summer of 1895. This decline can be illustrated by an incident that occurred in Asbury Park, New Jersey. For the summer season, six kinetoscopes with The Corbett-Courtney Fight were set up inside a building rented from the Asbury Park Amusement Company. This was the second year of kinetoscope exhibitions at the summer resort, but the success of the first season was not repeated. As a local newspaper explained in early August, "The kinetoscopes, although they give wonderful entertainment for those who like that sort of thing, do not seem to have been profitable thus far this summer."[63] Unable to pay the rent, the kinetoscope manager and some cohorts crept into the hall and started to remove the machines under cover of darkness. A night watchman discovered them, called the police, and warned the landlord. In the confrontation that followed the manager was outnumbered and was forced to abandon the attempted removal. The next day a distress warrant was issued turning the machines over to the local amusement company until proper payment was received.[64]

The manager's inability to meet expenses was perhaps not so unusual and symbolizes the wider problems facing kinetoscope entrepreneurs. Overseas, Maguire & Baucus faced serious competition. In London, Robert Paul was making duplicate kinetoscopes and his own original films. Paul's activities, moreover, were safe from legal action, since Edison had failed to take out foreign patents on his motion picture inventions. This severely reduced Edison's potential foreign sales. Domestic imitators also appeared, reducing sales and the price tag within the American market.[65] When the Lathams began to exhibit their crude eidoloscope projector in April 1895, this, too, deflected interest away from Edison's machine.[66] With the urging of Raft & Gammon, Edison began to experiment with projection. According to Terry Ramsaye, Edison sent experimenter Charles Kayser to the Kinetoscope Company's offices in New York, where he pursued these investigations. Nothing useful, however, materialized from these efforts.[67]

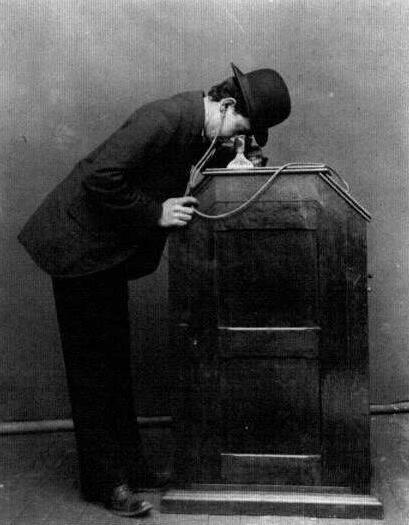

One serious effort to bolster the kinetoscope business was made in the spring of 1895: the kinetophone. A phonograph was placed inside a kinetoscope cabinet with rubber ear tubes protruding from a convenient location for the spectator. Recordings and films could then be loosely synchronized. The longstanding promise of a novelty that combined recorded sound and moving image was to be fulfilled. It was hoped that this would not only revive its novelty value but increase the range of available subjects. The local Orange Chronicle announced:

An unidentified phonograph parlor boasts a kinetoscope. By 1895 business had slowed.

With this combination wonderful possibilities are opened out before the public. An entire change will be made in the character of the objects and scenes taken by the kinetograph. Previously only scenes were taken in which there was a great variety of action, the element of sound being entirely disregarded. Hence such scenes as prize fights, skirt dances, clog dances and the like were taken. With the new combination, the eye and ear being both concerned, the range of subjects is largely increased, and many things that could not have been effectively taken under the principle of the kinetograph alone will now become available.[68]

This breakthrough was premature and no doubt forced by the onset of declining sales. Efforts to kinetograph and phonograph scenes simultaneously had been made, but without success (Dickson Experimental Sound Film and various illustrations testify to these attempts). Thus no new diversity of subject matter resulted. Rather, appropriate music was added to preexisting subjects. The Kineroscope Company announced, for example, that the kinetophone in its offices was featuring Finale of 1st Act of Hoyt's "Milk White Flag ": "as the band is

Looking at and listening to the kinetophone: a pastime that never became popular.

seen coming into view in the Kinetoscope, the music bursts forth with a volume and melody that is truly wonderful and realistic."[69]

The kinetophone was initially marketed in mid April for a cost of $400, $50 more than the kinetoscope. At least one was at Frank Harrison's parlor in Atlanta, Georgia, in May. Although he claimed that they increased business

threefold, Harrison had established a special arrangement with the Kinetoscope Company for the upcoming Cotton States' Exhibition, and his endorsement is hardly credible.[70] Within a short time, the price of the kinetoscope fell to $250 and the price of the kinetophone with it to $300. Demand for the kinetophone proved slight, only forty-five being sold.[71] Dickson's untimely departure from Edison must have harmed whatever slight prospects of success the kinetophone enterprise may have initially enjoyed.

As the kinetoscope and kinetophone novelties faded, Raft & Gammon faced fewer and fewer orders for its goods. Seeking to reverse this decline, they assigned employee Alfred Clark the responsibility for making new films. Clark, who looked after film production and sales for the Kinetoscope Company, tried to reorient and broaden the Edison Company's approach to production. That August and September he produced a group of motion picture subjects at the West Orange laboratory that were not tied to popular theatrical amusement, including several historical scenes based on well-known paintings or other iconography.[72]loan of Arc , which showed the French heroine being burned at the stake, and Rescue of Capt. John Smith by Pocahontas represented larger-than-life, semi-mythical moments. These films, which were taken outdoors, involved elaborate historical costuming. Only one survives, The Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots .[73] Its tableau-like, static quality highlights the moment when the ax descends, cutting off the queen's head. In fact, this effect was achieved using stop-action substitution: the filming was halted, while the actor (Robert Thomae in female garb) was replaced by a dummy; then the action and filming resumed. The camera stop was later cleaned up by splicing the two takes together so that the film appeared to consist of one continuous shot. Other scenes, including Indian Scalping Scene and Frontier Scene (later retitled Lynching Scene ), indicate a curious penchant for the gore of murders and executions, subjects regularly depicted in wax at the Eden Musee's Chamber of Horrors.

Demand for Clark's innovative films was modest. In the following months, the handful of new productions returned to tried and true subjects: Umbrella Dance and Acrobatic Dance , featuring the Leigh Sisters; Cyclone Dance and Fan Dance , with the Spanish dancer Lola Yberri. The declining kinetoscope business most affected those people who depended on it for their livelihood and resulted in career changes. James White and Charles Webster sold their kinetoscopes in August, with White returning to the phonograph business.[74] Clark likewise sought more secure employment in the phonograph field, with Webster joining Raft & Gammon to take his place.[75] Late in the year, Raft & Gammon went for months without selling a single machine, and the partners considered selling or even liquidating their business. Then they came across a screen machine that was far superior to the Lathams'. It soon returned them to the forefront of motion picture activity in the United States and in the process revived film production at the Edison Manufacturing Company.