"Telling a Story in Continuity Form"

In Paris, Alfred C. Abadie attended the opening of Méliès' Le Voyage dans la lune at the Theéâtre Robert-Houdin and then quickly purchased a copy to send back to Edison for duping.[148] Since Méliès knew Edison would dupe his films and so was unwilling to make a direct sale, Abadie's purchase had to be quite devious. According to Arthur White, "through a certain Charles Gershel, a French photographer, 23 Boulevarde des Capuchines, Paris, who had a brother-in-law in Algiers, who had a theatre, Abadie was enabled to buy prints of the latest Melies pictures, among them 'The Trip to the Moon.'"[149] By the beginning of October, Edison was selling copies of Méliès' burlesque space fantasy as a Class A subject.[150] Years later Porter recalled, "From laboratory examination of some of the popular films of the French pioneer director, George Melies—trick films like 'A Trip to the Moon'—I came to the conclusion that a picture telling a story in continuity form might draw the customers back to the theatres and set to work in this direction."[151] A key moment must have been the rocket landing on the moon. One shot ends after the rocket hits the Man-in-the-Moon in the eye, making him wince. In the succeeding shot, the rocket lands on the surface of the moon and its passengers disembark. The event is seen twice from different perspectives. While Méliès' double depiction of the landing had legitimate storytelling reasons, the overlap emphasized the continuities of action and narrative from one shot to the next. It is this kind of continuity that Porter examined, conceptualized, and applied in many of his subsequent films.

How They Do Things on the Bowery could be called an experiment in editorial principles. Its simple, comic narrative had been presented in Biograph's earlier, one-shot Uncle Si's Experiences in a Concert Hall (photographed by F. S. Armitage on April 13, 1900).

HOW THEY DO THINGS ON THE BOWERY

Scene Bowery. Young woman drops her handkerchief while passing a Rube. He picks it up and gives it to her. She induces him to go into a side door of a saloon.

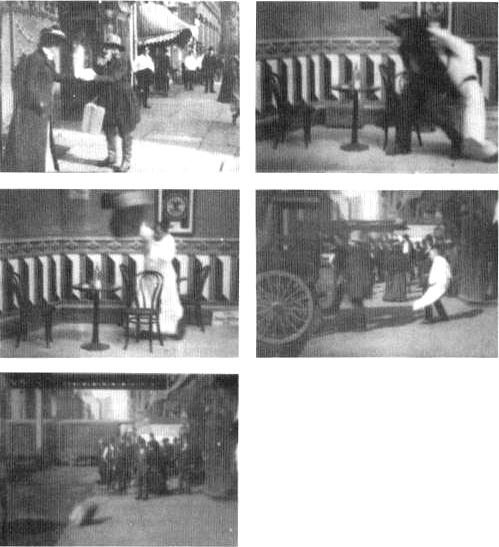

How They Do Things on the Bowery.

Second scene, saloon. Rube and woman enter, take seats at table and order drinks. While the Rube is paying for same, woman puts knock-out drops in the Rube's glass. They drink and the Rube falls asleep. Woman takes all his valuables and leaves. Waiter wakes him up. He discovers his watch gone, fights with waiter, and is thrown out. Third scene, outside of saloon. Police patrol drawn up. They put Rube in and drive off. Length 125 feet.[152]

In the second shot of the film, the prostitute and Uncle Josh sit at a table in a saloon and have a drink: she slips him a Mickey Finn, steals his wallet, and leaves. When the waiter finds Uncle Josh asleep, he kicks the rube out and throws his suitcase after him. In the third shot, a paddy wagon comes down the street and parks outside a building. The waiter dumps Uncle Josh into the gutter and again throws the suitcase after him.

The spatial and temporal relations between shots 2 and 3 are determined by the continuity of action as the waiter throws Uncle Josh out of the saloon. These actions, coming as they do at the end of both shots, reveal the relationship between the two scenes only in the final moments of the picture. Shots 2 and 3 are finally shown to take place in contiguous spaces, inside and outside the saloon. Shot 3 repeats the same time period shown in shot 2, employing a temporal repetition from a different camera position. This temporal construction, which was implicit in Sampson-Schley Controversy and Execution of Czolgosz and was an exhibition possibility when two cameras simultaneously filmed the christening of Kaiser Wilhelm's yacht Meteor , was now made explicit by the producer's assumption of editorial responsibility and the repetition of specific actions in contiguous shots. It is this concept of continuity that Porter would elaborate in Life of an American Fireman and many subsequent Edison films.

In How They Do Things on the Bowery , Porter also used a panning camera to follow action in the final shot, as the paddy wagon backs up to the saloon. For the first time Porter applied the mobile camera associated with actuality production to fiction filmmaking. Heightening a sense of realism for spectators, this procedure to some extent departed from early cinema's presentationalism. And yet the cinema's syncretism easily incorporated and contained these changes. The use of a panning camera established a much stronger sense of off-screen space. To use an insight of André Bazin's, the edges of the picture were perceived much more as a mask and much less as a frame or proscenium arch.[153] This heightened sense of a spatial world thus coincided with the introduction of a new editorial technique that specified the spatial as well as temporal relations between shots. Such camera pans would remain a key element in Porter's cinematic repertoire over the next six years. How They Do Things on the Bowery laid out the representational system that Porter would use during his years at Edison. Yet it was with Life of an American Fireman that this was elaborated, refined, and ultimately found its first large-scale, successful realization.