Porter Becomes an Edison Employee

By the fall of 1900 the Edison Company was reorganizing its Kinetograph Department and upgrading its technical system. Edwin Porter, with his mechanical ingenuity and experience, was the appropriate person to hire for the latter effort. The experienced operator had his own reasons for joining the Edison staff. His small factory for manufacturing projectors had recently been wiped out by fire.[1] Since traveling motion picture exhibitors were suffering through a difficult period, Porter was not eager to pursue such a commercial venture if other options were available. The exhibitor's admiration for Edison was undoubtedly another influential factor. In the end, Porter was added to the inventor's payroll a few days before Thanksgiving 1900. He was employed to "improve and redesign moving picture cameras, projecting machines and perforators," based on the superior equipment he had built and used at the Eden Musee.[2]

Edison Laboratory in West Orange, ca. 1900. Black Maria is in center.

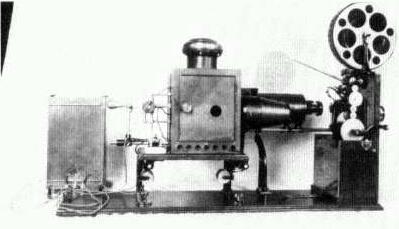

According to Porter, "Mr. White, also Mr. Gilmore, recognized the superiority of my machine over theirs and they engaged me more as a technical man to improve their machine."[3] Edison advertisements described the 1901 Model Projecting Kinetoscope, which benefited from Porter's improvements, as "a complete revolution in projecting machines."[4] Besides the customary claims to a steady, flickerless image, the Edison machine "is equipped with the only perfect take up device which has ever been constructed to reel up 1,000 ft. of film without hitch or failure. Shows both stereopticon slides and animated pictures. One person can work the whole machine. It has a new adjustable arc lamp which is a marvel in itself. The lamp house is adaptable to any kind of illuminant known to the profession." By 1901, after having incorporated improvements from Albert Smith's vitagraph and the Eden Musee's cinematograph, Edison's projecting kinetoscope was among the best in its field. At a cost of $375 in labor and materials, Porter also constructed a new printing machine in January and early February.[5]

By the fall of 1900 the Edison Company had decided to build a new studio that would ensure a steady supply of films and improve its competitive position. The evident stabilization of exhibition outlets through vaudeville theaters made this appropriate. Because the demand for film programs had fluctuated between 1896 and 1899, relying on licensees to produce films and locate exhibition opportunities had kept expenses and risk low. Now that moving pictures were a permanent feature and exhibitors required a consistent supply of films, a new approach was merited. The result was the nation's first indoor, glass-enclosed film studio where pictures could be produced year-round—a definite improvement over both the Biograph and Vitagraph companies' open-air rooftop stages.

The Edison Projecting Kinetoscope, ca. 1901.

Unlike the Black Maria, the new studio was to be located in the heart of New York's entertainment district. All the personnel and materials needed for regular film production were at hand.

In October 1900 the Kinetograph Department rented the top floor and roof of 41 East Twenty-first Street for $150 a month. The Hinkle Iron Company was hired "to furnish, deliver and erect complete and in good substantial and workman-like manner a photographic Studio on roof" at a cost of $2,800.[6] The first expenditures for the New York studio were dispersed in December for "Pay Roll—Photo Gallery"—a total of $95.77. Another $10 was spent "hoisting 3 drums and shafting." On January 12, 1901, E. E. Hinkle announced that the building was complete after a mason had pointed up all the front and rear fireproof blocks at the studio. By mid February the studio was in working order.[7]

The Edison Company shared its space with Percival Waters' Kinetograph Company, which moved from offices across the street even before construction was completed. According to Waters, the space was

approximately 90 feet by 20 feet and on the roof above this floor there was a large studio occupying substantially the entire roof, fitted up especially for the purpose of taking moving pictures. . . . The proposition was made to me, and I accepted it, by which I was to pay the agent of the building monthly in advance $150., the entire rent for the top floor and the studio and I was to receive credit at the end of each month on my account with the Edison Company for $110, making my rent $40. The Edison Company was to have the exclusive use of the studio on the roof and a room approximately 8 × 10 feet lighted by a sky light and another room approximately 25 feet by 10 feet electrically lighted which was used as a dark room and dressing room and access to these two rooms through my place of business and the privilege of using the front rooms on my floor as dressing rooms. The company was also to have the use of

Blueprint for Edison's new motion picture studio on Twenty-first Street, New York.

the telephone, have such electric light as was needed and the use of my shop which I fitted up with a complete set of tools which they did use from time to time in connection with repairs to machines and cameras in connection with their operation of the studio and the producing of pictures there. They also had the use of my projecting machines for the purpose of exhibiting and testing their films.[8]

Porter recalled that "after being with [the Edison Company] a short time and as they were in need of a cameraman and producer, I was given charge of the first skylight studio in the country."[9] Porter actually had little experience as a cameraman; he was hired because of his considerable knowledge of cinematic practices and because his background as an electrician and machinist enabled him to put the studio in working order and to keep it that way. On staff, he was available to further improve the projecting kinetoscope and Edison's cameras. In addition, Edison executives needed someone who would not desert the studio if the inventor's patents suffered setbacks in the courts. Many of the more experienced cameramen could not have been trusted precisely for this reason. Porter's self-effacing manner, his emulation of Edison, and his lack of conflicting business interests all suited him to the company's needs. Also, studio productions did not then have the same importance—vis-à-vis news films and other actualities—that they were later to assume.

Porter's move into filmmaking occurred, moreover, within what might be called a collaborative system of production. Collaboration was, as already shown, familiar in the early years of film—whether between Porter and Charles H. Balsley, Dickson and Heise, White and Blechynden, or J. Stuart Blackton and Albert E. Smith. Now Porter shared his new responsibilities with George S.

Fleming, an actor and scenic designer who started working for the Edison Company on January 13, 1901. Fleming earned $20 per week, while Porter received only $15. This relationship with Fleming would provide Porter with a model for subsequent organizations of film work. In the years ahead, whether with Wallace McCutcheon, James Searle Dawley, or Hugh Ford, Porter would seek out a similar collaborative working method. Porter would feel most secure dealing with the filmic issues (camerawork, editing, special effects, camera tricks, etc.) and look to others to handle the actors. Although the stories and scripts for these subjects came from many sources, Porter would customarily shape them to his own sense of the commercially popular.

Although this collaborative system typified pre-Griffith film production, it has been little recognized. Janet Staiger has articulated the general historical consensus in characterizing pre-1907 filmmaking as relying on the "cameraman system." In the cameraman system, a single individual is responsible for the production of a given film.[10] The notion of a single cinematographer improvising short skits, or, more typically, traveling about the country taking actualities, resonates with the concept of early cinema as simpler and more "primitive."

The cameraman system was indeed employed during the pre-Griffith era, but then it was used in later years as well. The collaborative approach, with its informal exchange of ideas and sharing of roles, was more characteristic of the early period. Although this working method typically involved two key individuals, others also made contributions. Thus, James White assisted Porter and Fleming on such studio productions as Execution of Czolgosz and Life of an American Fireman . Collaboration, however, frequently went beyond Porter, Fleming, and White to include members of the staff whose contributions would never be expected (or even tolerated) in later, more hierarchical and labor-specialized organizations. While filmmakers of this period, including Porter, did occasionally have to work alone, this collaborative approach was preferred.

The new studio changed the balance of power between the Edison Company and its licensees. On January 10th, White and Gilmore terminated their licensing agreement with the talented, but difficult, American Vitagraph Company, after Blackton and Smith claimed that they were unable to pay a 10 percent royalty on exhibition income.[11] In the future, the Vitagraph owners were theoretically restricted to showing only Edison films. Though exhibiting European subjects in order to keep their business afloat, they ceased virtually all production activities. Only William Paley continued to operate under formal Edison auspices.

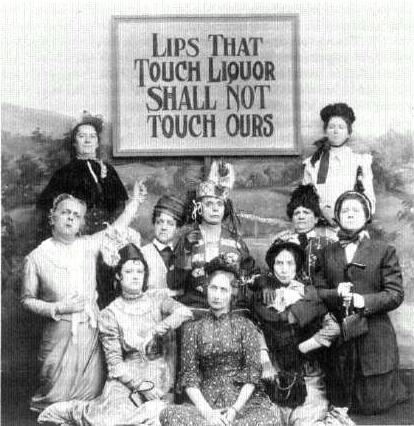

By mid February, Porter and Fleming were turning out short films; one of the first, Kansas Saloon Smashers , was the occasion for a rare publicity still. Excepting a few winter scenes (Ice-Boat Racing at Red Bank, N.J. ) and news films of McKinley's second inauguration (President McKinley and Escort Going to the Capitol ), most Edison subjects from the winter of 1901 were shot in the studio. Full-scale production of short comedies continued at Edison, while

Publicity still for Kansas Saloon Smashers.

Biograph, with its outdoor facilities, suspended most production. Edison's investment was already paying off.