4

Cinema, a Screen Novelty: 1895-1897

The first commercially viable motion picture projector in the United States was known as "Edison's Vitascope." This successful adaptation of Edison's films to the magic lantern not only resuscitated kinetographic activities but brought Edwin Porter into the emerging film industry. Unlike the Lathams' eidoloscope, the vitascope had an intermittent action that halted each frame of film in front of the light source, providing the basis for modern motion picture projection. Despite its name, this "screen machine" was the invention of two young men from Washington, D.C., C. Francis Jenkins and Thomas Armat, who originally called it the "phantoscope." The two inventors quarreled, however, shortly after their first commercial exhibitions at the Cotton States' Exposition in Atlanta, Georgia, during October 1895. Acting independently, each tried to maximize his claims and commercial opportunities. In early December, Armat arranged an exhibition for Frank Gammon in the basement of his Washington office.[1]

Raft & Gammon, discouraged over the future prospects of the peep-hole kinetoscope business, greeted Armat's machine like drowning men who had unexpectedly discovered a life raft. Nonetheless, a month of contract negotiations and delays followed the basement demonstration as they sought Edison's blessing for their use of Armat's machine. Edison's control over film production made the inventor's cooperation essential. William Gilmore, vice-president and general manager of the Edison Manufacturing Company, played a key role in these discussions. A hard-headed, if overly aggressive, businessman, Gilmore had little difficulty interpreting the Edison Company's discouraging balance sheets. The Wizard's motion picture business was doing poorly and was increasingly threatened by independent motion picture activities both domestically and overseas. Gilmore was familiar with the Lathams' eidoloscope and possibly

with the work of W. K. L. Dickson on the mutoscope (a peep-hole device similar to the kinetoscope). Rumors of the Lumières' film projections in Paris may also have reached the Orange office. Since Edison's half-hearted efforts to develop a projecting machine had been unsuccessful, the phantoscope posed yet another threat. But it was one that the Edison organization now had the opportunity to coopt. Gilmore was therefore predisposed to work with Raff &; Gammon. Such a move would not only bolster sales of hardware and film, but maintain a determining presence in the industry and give company machinists valuable experience with the workings of the new apparatus.

At a meeting on January 15, 1896, Raft & Gammon completed negotiations with Edison and Gilmore. The Edison Company would manufacture the vita-scope projectors from Armat's prototype and provide the necessary films. Delighted, Raft & Gammon sent a telegram to Armat announcing that the terms of this agreement were "exceedingly favorable for all. Contract will be signed and forwarded tomorrow."[2] This contract gave Raft &; Gammon "the sole and exclusive right to manufacture and rent or lease or otherwise handle (as may be agreed upon in this contract or by future agreement) in any and all countries of the world the aforesaid machine or device called the 'Phantoscope.' "[3] In exchange Armat received 25 percent of the gross receipts gained by the sale of exclusive exhibition rights for territories and 50 percent of the gross receipts (minus the cost of manufacture) for other areas of the business, particularly the rental of machines. Raff & Gammon gained the exclusive exhibition rights for New York City, while Armat retained the rights for Washington, D.C.[4] No mention was made of Jenkins in the contract: Armat represented himself as sole owner of the invention.[5]

In mid February 1896 the Armat machine was renamed the "vitascope," perhaps once Raft & Gammon belatedly recognized that Jenkins, who had coined the term "phantoscope," could disrupt their plans and become a potential competitor.[6] Certainly Jenkins had become an active threat by early March.[7] Under such circumstances, extensive publicity was considered essential to the vitascope's success. Raft suggested that "in order to secure the largest profit in the shortest time, it is necessary that we attach Mr. Edison's name in some prominent capacity to this new machine. While Mr. Edison has no desire to pose as the inventor of the machine, yet we think we can arrange with him for the use of his name and the name of his manufactory to such an extent as may be necessary to the best results. We should of course not misrepresent the facts to any inquirer, but we think we can use Mr. Edison's name in such a manner as to keep within the actual truth, and yet get the benefit of his prestige."[8] It was an arrangement that benefited everyone concerned. Raft & Gammon garnered the necessary publicity for their enterprise, while Edison kept his name before the public. Since people simply assumed that Edison must be the inventor, use of his name enhanced the legend of the Wizard's fecund genius. This "biographical legend" was another product of the inventor's "genius." Edison's image as

a mythic hero allowed him to acquire financing and manipulate legal and commercial situations in unprecedented ways.[9]

The desire to exploit Edison's name was compelling from a business viewpoint.[10] As Raft & Gammon told Armat: "No matter how good a machine should be invented by another, and no matter how satisfactory or superior the results of such a machine invented by another might be, yet, we find the great majority of parties who are interested, and who desire to invest in such a machine, have been waiting for the Edison machine, and would never be satisfied with anything else, but would hold off until they found what Edison could accomplish."[11] Armat acquiesced. To the public and prospective investors, the vitascope was to be the machine Edison had promised them when the Lathams unveiled their imperfect eidoloscope a year before.[12]

By late March the threat posed by rival machines from abroad had created an urgent situation. As Raft reported: "It becomes more apparent every day that we must take some action with regard to the European machine which is now being exhibited in London, and which we hear is creating a sensation there. If the reports we receive are true, the machine must be quite satisfactory, and we hear of the parties exhibiting the interior of a railway station, with train coming in and going, parties moving about, etc., etc. We also hear of other interesting subjects which they show."[13] The term "chestnuts," which referred to jokes or amusements that had lost their entertainment value through overuse, could be applied to the Edison subjects left over from the peep-show kinetoscope.[14] These would not compete effectively with novel scenes taken abroad. The need for fresh, new subjects had to be added to Raft & Gammon's list of concerns.

For the vitascope group, it was extremely important that their machine enter the entertainment field first. The significance of such a "first" was not one of legal/historical priority. Rather, with projected moving pictures regarded as a novelty, it was essential to be perceived as the first by the amusement-going public, a phenomenon that involved orchestrating one's publicity very carefully. Although moving pictures had been projected in some form within the United States for almost a year, no effort had quite achieved the necessary threshold of recognition. The organization that first achieved this goal would be hailed as the original and its competitors considered imitations. Thus, when Raft & Gammon heard that amusement enterprises in New York were contemplating the addition of the European machine to their shows, the entrepreneurs preempted these plans by quickly preparing for the vitascope at Koster & Bial's Music Hall, continuing a relationship with its management that had earlier provided the kinetograph with a bevy of star performers.

The Edison tie-in was maximally exploited. Several weeks before the Koster & Bial's debut, a press screening was arranged. Although the inventor had a private look at the vitascope on March 27th, this preview was staged at the Orange laboratory on April 3d. The "Wizard" not only attended but played the

role of inventor assigned to him. In successive headlines, the New York Journal announced:

LIFELESS SKIRT DANCERS.

In Gauzy Silks They Smirk and Pirouette at Wizard Edison's Command.

Perfect Reproduction of Noted Feminine Figures and Their Every Movement.

SUCCESSFUL TEST OF THE VITASCOPE.

By it the Great Inventor Will Give Representations of Theatrical Performances with Faces and Forms In Every Detail.[15]

Like the hypnotist Svengali in Trilby , the inventor seemed to command every move and gesture produced by the dancing girls on the screen. They were his creations, objects of desire that he could manipulate to gratify the "bald head row" of older men who sat in the front of the orchestra, the better to eye the Music Hall's female performers. Other newspapers contributed additional accolades to the inventor's genius. Such ballyhoo created anticipation and diverted attention away from the work of the Lumières, the Lathams, and Jenkins.

The Vitaseope's Premiere

Raff & Gammon moved quickly forward with their first public exhibitions of Edison's vitascope. They sent Charles Webster to Europe with one screen machine on April 22d.[16] Only when he arrived in London and saw the Lumière cinématographe did it become fully evident that the vitascope would face insurmountable difficulties in foreign markets. To replace their absent employee, Raff & Gammon hired James White, Webster's former associate, in early April for $75 a month.[17] Arrangements were soon finalized for the Koster & Bial's premiere on April 23d. The fee was set at $800 per week, providing Raff & Gammon with a bountiful income during the ensuing four-month run.[18] Thomas Armat acted as moving picture operator (i.e., projectionist) for the first week, after which he was succeeded by his brother. White assumed overall responsibility for the Koster & Bial's showings.[19] Edwin Porter, while still in the navy, may have helped in his off hours to install the electrical system that ran the machine.[20] The opening night response was ecstatic. "WONDERFUL IS THE VI-TASCOPE," proclaimed the New York Herald .[21]The New York Times enthused:

The new thing at Koster and Bial's last night was Edison's vitascope, exhibited for the first time. The ingenious inventor's latest toy is a projection of his kinetoscope

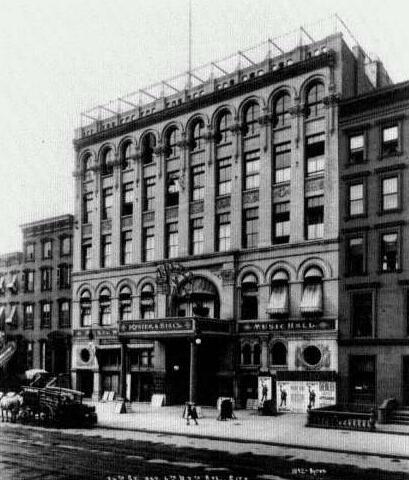

Koster & Bial's Music Hall at the time of the vitascope premiere.

figures in stereopticon fashion, upon a white screen in a darkened hall. In the centre of the balcony of the big music hall is a curious object, which looks from below like the double turret of a big monitor. In the front of each half of it are two oblong holes. The turret is neatly covered with the blue velvet brocade which is the favorite decorative material of this house.[22]

The New York Daily News added:

On the stage, when it was ready to show the invention a big drop curtain was lowered. It had a huge picture frame painted in the center with its enclosed space

Interior of Koster & Bial's. The vitascopes are hidden within

their turret-shaped housing in the second mezzanine.

white. The band struck up a lively air and from overhead could be heard a whirring noise that lasted for a few moments; then there flashed upon the screen the life-size figures of two dancing girls, who tripped and pirouetted and whirled an umbrella before them. The representation was realistic to a degree. The most trifling movements could be followed as accurately as if the dancers had been stepping before the audience in proper person. Even the waving undulations of their hair were plainly distinguishable. The gay coloring of the costumes was also effectively shown.[23]

Six films were shown, but only five were made by the Edison Company. The first to be projected was a tinted print of Umbrella Dance , with the Leigh sisters. Subsequent views included Walton and Slavin (a burlesque boxing bout from 1492), Finale of 1st Act of Hoyt's "Milk White Flag " (not listed on the programme), and The Monroe Doctrine . Made in preparation for the vitascope debut, The Monroe Doctrine offered a new type of subject matter, a comic allegory that was overtly political. Referring to a recent incident in South America, this political cartoon on film showed John Bull and Venezuela fighting. "Uncle Sam appears, separates the combatants and knocks John Bull down."[24] The patriotic audience was delighted and "cheers rang through the house, while somebody cried, 'Hurrah for Edison.' "[25] The final film was of a skirt or ser-

Rough Sea at Dover (1895), taken by R. W.

Paul in England. The hit of opening night.

pentine dance. Although the dancer was blonde, none of the reviews indicate she was Annabelle.

Opening night critics were most impressed by the second film to be shown, Rough Sea at Dover , of a wave crashing on a shore. This subject, the only one not shot in the Black Maria and the only "actuality," had been sent to Edison by his English competitor Robert Paul:

The whirr of the machine brought to view a heaving mass of foam-crested water. Far out in the dim perspective one could see a diminutive roller start. It came down the stage, apparently, increasing in volume, and throwing up little jets of snow-white foam, rolling faster and faster, and hugging the old sea wall, until it burst and flung its shredded masses far into the air. The thing was altogether so realistic and the reproduction so absolutely accurate, that it fairly astounded the beholder. It was the closest copy of nature any work of man has ever yet achieved.[26]

Paul's film pointed out the possibilities of aggressively assaulting or confronting spectators with the image rather than simply using the camera for passive display. Patrons in the front rows were disconcerted and inclined to leave their seats as the wave crashed on the beach and seemed about to flood the theater.

Like Edison's peep-hole kinetoscope, the vitascope used a twenty-second loop of film spliced end to end and threaded on a bank of rollers. Raft & Gammon suggested that "a subject can be shown for ten or fifteen minutes if desired, although four or five minutes is better."[27] When, as in most cases, one projector was used, a two-minute wait occurred between films. At Koster & Bial's in New York, however, projectors worked in tandem and there was no wait. Even under these conditions, films still had to be projected for at least two minutes while a new film was threaded on to the other projector. Thus, each subject was necessarily shown at least six times. As one journalist remarked, "The scene is repeated several times, then the click click stops, and the screen is blank. A moment's interval, then a pretty blonde serpentine dancer appeared."[28] Although two projectors eliminated waiting periods between films, they did not

reduce the number of times a film was projected at one showing, nor were they customarily used to juxtapose related images. There was little room or concern with editorial techniques in these first exhibitions. Films were usually shown separately and treated as discrete images. In Cleveland, for example, waits were eliminated by alternating films with musical selections by the Chicago Marine Band.[29] Later, some exhibitors filled these interludes by showing "dissolving views" (i.e., lantern slides).

The absence of complex cinematic meanings has sometimes been seen as proof of the screen's primitive qualities, but this simplicity effectively emphasized the novel contribution of moving pictures to screen practice. Audiences, while accustomed to projected photographs that were static and to projected nonphotographic images that could move, were tremendously impressed by animated photographs projected on the screen. "Life-like" motion in conjunction with "life-like photography" and a "life-size" image provided an unprecedented level of verisimilitude. And yet cinema's novelty period involved much more than the exhibition of lifelike images. The rapid diversification of subject matter and the increasingly frequent sequencing of images constantly renewed cinema's ability to intrigue and entertain even regular vaudeville customers during the 1896-97 theatrical season. The first year of projected motion pictures, often called cinema's "novelty period," was one of multiple, successive innovations and not, as some have suggested, an undifferentiated period that simply relied on the new sensation of projected motion pictures.

Producing Films for the Vitascope

Revisionist historians have argued that Edison film production was grossly inadequate.[30] Certainly there were problems, and yet during the summer of 1896, the Edison Company remained the only American-based enterprise that produced a significant number of film subjects. With the Vitascope enterprise preparing for its debut, Raft & Gammon desperately needed new pictures. The recent inactivity was apparent when Frank Gammon took several performers to West Orange on March 24th and found the Black Maria in a dilapidated state. He "had great difficulty in persuading them to go in to the theatre dressed in their thin silk costumes, as it was just like going out into an open field in mid-winter."[31] The raised roof could not be closed to protect the dancers during preparations and rehearsals. Several actors, hearing of these conditions, refused to be filmed. Moreover, the studio was inconveniently located for those working in New York City. Although the vitascope's success and the onset of warm weather improved matters, the rate of production at the Black Maria would never again approach the levels of 1894.

At first the production practices of the kinetoscope era continued. Edison personnel, notably cameraman William Heise, coordinated filming activities, with Raft & Gammon acting as producers. Increasingly, however, James White must have been designated to fill this role. A new collaborative relationship

The May Irwin Kiss. The most popular Edison film of 1896.

was emerging, though this relationship was not yet in effect when The May Irwin Kiss was filmed in mid April. While William Gilmore stood by, Heise kinetographed this brief, fifteen-second scene showing the culminating moment of a popular musical farce, The Widow Jones . It was made at the behest of the New York World , which devoted a full page to "May Irwin and John Rice Posed Before Edison's Kinetoscope—Result: 42 Feet of Kiss in 600 Pictures."[32] The promise of extensive publicity may have induced the two stars to travel to West Orange. The scene was carefully rehearsed and then photographed only once. Perhaps intended for the premiere, the picture was not shown until the second week of the vitascope's New York run. It was immediately hailed as a hit. Several weeks later, Cissy Fitzgerald, the girl with a famous wink, likewise performed her specialty for the Black Maria kinetograph.[33]

Coinciding roughly with the filming of Cissy Fitzgerald , the Edison Company completed construction of a new, portable camera. "Our portable taking machine is now completed," Raft wrote Peter Kiefaber on May 6th, "and if tomorrow is a clear day, we expect to secure some every-day street scenes in New York."[34] Yet it was not until May 12th that Heise set to work photographing actualities similar to those that the Lumières were showing in Europe and the Lathams in the United States.

The first Edison street scene was Herald Square . The newspaper after which the square was named reported: "The photographers settled down to work at two o'clock yesterday afternoon, when the square was crowded with cable cars, carriages and vehicles of all sorts, while now and then an 'L' train would thunder by. They chose a window on the lower end of the square, where they were within full view of the Herald Building, and at the same time took in Broadway and Sixth avenue for a radius of several blocks."[35] When the film was shown at Koster & Bial's Music Hall, spectators may have had the pleasure of seeing the exterior of the building inside of which they were sitting (assuming, of course, the theater was within camera range). In this play with space, outside became inside—a somewhat disconcerting experience, greatly heightened by the lifelike quality of the image. Central Park , showing the main fountain, was taken on the same day. Within a week Elevated Railway, 23rd Street, New York was also shot. Six weeks before the American debut of the Lumière cinématographe, Edison actualities were being shown in American theaters. For New Yorkers at least, these were "local views" of locations they encountered in the course of their everyday lives.

Scenes of everyday life significantly diversified the kinds of subject matter that Edison was making. For almost the first time, Edison subjects had no direct ties to popular amusements or leisure activities. Nor did these images have anything to do with either sex or violence. Instead, they recalled the types of photographic images that were routinely presented in lantern shows to religious groups and cultural elites. Of course, these images were familiar, even banal, in terms of subject matter and framing. They would have elicited little reaction— except that they moved. "The Twenty-third street station of the New York elevated was a stirring picture, wherein the train came rushing along at top speed, so realistically as to give those in the front seat a genuine start," remarked one critic.[36] Not only were these films much cheaper and easier to make than those previously taken in the Black Maria, they proved to be at least as popular with audiences.

In late May or early June, Heise and possibly James White took their new portable camera on an ambitious trip to Niagara Falls, long a privileged subject for artists and photographers. Although the Lathams had already made films of this tourist attraction, that did not prevent the vitascope group from treading in their footsteps. The Edison crew shot the falls from a dozen different camera positions using 150-foot film lengths. The results were somewhat disappointing, and only four scenes were finally distributed. The most enthusiasm centered on Niagara Falls, Gorge :

a panoramic picture obtained from the rear end of a swiftly moving train on the Niagara Gorge railway, and one that has never been equalled for completeness of

detail and general effects. In this view the stone bluffs of the gorge, the telegraph poles, rail fences and the waters of the great river go rushing by with incredible swiftness, but yet plain enough for one to note everything in a general way, just as though seated in an observation car. The Whirlpool rapids are in sight one moment and lost to view the next, their whirling eddies and foam-flecked waves sparkling in the sun's rays, forming a very beautiful picture.[37]

Placing the kinetograph on a train was inspired by Grand Canal, Venice, a Lumière film in which the camera was situated on a gondola. (A print of this subject had been surreptitiously acquired by Albert Bial in Europe and turned over to Raft & Gammon in late March.) The results helped to establish an association between actuality subjects and a mobile camera that would be strengthened over the next several years. Two other scenes were of the American Falls from the east and west sides. In Boston, these were shown consecutively— the juxtaposition suggesting at least a rough spatial relationship between shots.

The new, portable camera also enabled Edison and Vitascope Company personnel to reconceptualize their filming of performers and sporting activities. Instead of bringing entertainers to the Black Maria, a kinetograph team could now go to amusement locales and capture subjects in their customary surroundings. This new opportunity was exploited in late June while Heise and a Vita-scope representative were active in Brooklyn. On June 23d they shot The Suburban Handicap , showing Navarre winning the horse race at Gravesend Race Track.[38]Parade of Bicyclists at Brooklyn, New York was made four days later. Although participating bicycle clubs still had exclusively male memberships, the bicycle fad had become a way for men and women to socialize together casually.[39] Additional films focused on another site where the codes of social contact had loosened—Coney Island.[40] Taken at Bergen Beach, where the vitascope was being shown, these included Shooting the Chutes, Ferris Wheel , and Streets of Cairo . The Ferris wheel, almost 200 feet high, was a local landmark that provided visitors with a magnificent view of Jamaica Bay. Streets of Cairo (later retitled Camel Parade ) was taken at the Egyptian Encampment.[41] Paul Boyton's "Shooting the Chutes" was a hit amusement ride (imitations were springing up everywhere). Two shots of this attraction were taken, "the first showing the shoot down the incline and the other the dash into the water."[42] These separate views may have been part of a single 150-foot subject, making it one of the first instances in which the producer assumed an editorial role, juxtaposing two spatially and narratively related shots.

Recognizable, if highly specialized and ephemeral, "genres" were established and/or developed during the summer months. The Haymakers at Work and Carpenter Shop recalled the first workplace films. One subject continued the filming of burlesque boxing matches by depicting a male-female duo. It combined sexual suggestiveness with violence in a single motion picture subject for perhaps the first time. Bathing Scene at Coney Island , taken in early July, not

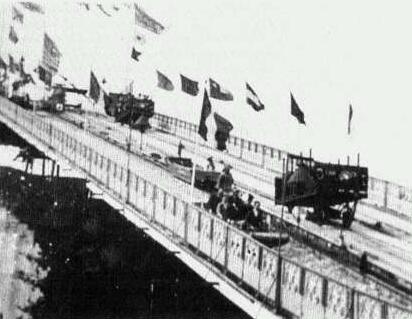

Shooting the Chutes, showing the descent down the incline.

only continued the documentation of that popular amusement resort but provided a variation on the popular Rough Sea at Dover . All these films were taken with either 50-foot or 150-foot rolls of films. While 50-foot sections of the longer films were often sold, these remained the two standard lengths.

The Lumière influence on Edison production was wide-ranging and strong. Short comedies, reminiscent of the Lumières' The Gardener and the Bad Boy , (L'Arroseur arrosé ) appeared. These included two variations on that prototypical gag in which the bad boy plays a trick on the gardener and gets spanked for his prank. In one Edison version the gardener was male, in the other female. In The Lone Fisherman a man casts for fish from a plank cantilevered off a bridge. His friends come and upend the plank, sending him into the water. Street scenes continued to abound (Street Sprinkling and Trolley Cars, Deadman's Curve , etc.). Lumière military scenes, which had taken the vaudeville circuit by storm, were quickly and consciously emulated. Heise and his crew photographed Firing of Cannon at Peekskill by the Battery of Artillery and at least one other subject at the New York State militia encampment by the end of July.[43]

The production of news film was spurred by the screening of the Lumières' attention-gathering The Coronation of the Czar of Russia at Keith's Union

Square Theater in late July. A month later the kinetograph team took The Arrival of Li Hung Chang , depicting the Chinese viceroy at New York's Waldorf Hotel. Li Hung Chang having arrived on the S.S. St. Louis , they also filmed several scenes related to the ship's departure (Steamer "St. Louis" Leaving Dock, Baggage Wagons ). Moreover, the quotidian Ferryboat Leaving Dock, New York suddenly enjoyed a second life as the timely news subject Steamer "Rosedale " when that ferryboat sank in New York harbor.

The paucity of surviving films makes it difficult to characterize the results of all this activity in very great detail. Terry Ramsaye reports that the portable camera was placed on the roof of the new Raft & Gammon headquarters at 43 West Twenty-eighth Street. At this makeshift studio, performers and small fictional scenes could be conveniently photographed. Although dancers may have dropped by the midtown location to appear in scenes such as Couchee Dance , it is not known which scenes were shot there. Candidates include Irish Way of Discussing Politics , a reworking of A Bar Room Scene , and Watermelon Contest , shot against a plain background and showing two "darkies" guzzling watermelon. So too are three scenes of cartoonist J. Stuart Blackton performing lightning sketches, each taken in mid August with 150-foot loads of film. The most successful, Edison Drawn by "World" Artist , was often used to conclude a film program on "Edison's Vitascope."[44] When shown at Proctor's Pleasure Palace in mid September, it was declared "the most curious and interesting of the new views" and was kept on the bill in subsequent weeks.[45]

A number of Edison films were designed to elicit political reactions from theatrical audiences; the theater was then a site where partisan political opinions could be expressed through shouts of approval or disdain. That The Monroe Doctrine was one of the first films made for projection was not, therefore, fortuitous but a calculated attempt to find favor with Koster & Bial's patrons. Its success was followed by Blackton Sketches, No. 2 (Political Cartoon) , in which Blackton rapidly draws likenesses of President Grover Cleveland and candidate William McKinley (rather than his Democratic-Populist rival, William Jennings Bryan). The film begins with a patriotic image of America's commander in chief, then moves on to suggest McKinley as his likely successor. With pro-Republican audiences predominating at the Music Hall and other New York theaters, the response must have been electric. Irish Way of Discussing Politics , in which two Irishmen discuss politics over a glass of whiskey, lampooned the Tammany Hall crowd. Likewise, in Pat and the Populist , the bricklayer Pat is approached by a Populist office seeker and "shows his displeasure by dropping bricks on the politician."[46] Not all images were resolutely anti-Democratic. When Bryan was campaigning in New Jersey, Heise took a news/ political film—Bryan Train Scene at Orange . Yet such a film was not necessarily meant to be pro-Bryan. Rather it could be exhibited ambiguously and elicit both cheers and catcalls, generating an informal opinion poll from an audience.

Throughout the summer and into September, Edison retained a virtual monopoly over the production of American subjects. Lumière films were not taken in the United States until September and not shown here until November. W. K. L. Dickson and the American Mutoscope Company photographed American subjects during the summer, but did not begin their exhibitions until September. Only the Lathams competed in this regard; but their limited number of subjects, inferior projection system, and internal squabbles hindered their effectiveness. With the Edison Manufacturing Company producing an adequate number of new subjects during the summer and early fall, the problems encountered by the Vitascope group occurred principally in other areas.

The Vitascope Group

In a number of crucial respects, the Vitascope organization was typical of film companies as the novelty era began. It manufactured its own equipment and made its own films. In addition, it retained control over exhibition as well as production. In fact, the four leading rivals had incompatible technologies— the vitascope, eidoloscope, cinématographe, and biograph—and thus each company had to operate in a self-contained fashion. However, the Vitascope organization was uniquely burdened by a loose affiliation of individuals and groups, whose interests often did not coincide. At the center was the Vitascope Company, incorporated by Norman Raft, Frank Gammon, and James White (as the third member of the board of directors, with one share of voting stock) in early May.[47] (This was one indication that the stockholders of Raft & Gammon's old Kinetoscope Company were not to play a part in this new enterprise. In fact, it was soon liquidated.) Raft & Gammon acted as a clearing house for the entrepreneurs, who had bought exclusive exhibition rights at considerable expense. As these owners were desperately trying to recoup their investment, they had little sympathy for, or understanding of, the company's problems. Raft & Gammon, moreover, did not control the Edison Company's activities and could only plead for quick action. Thomas Armat and T. Cushing Daniel, with their patent applications, were yet another affiliated organization. Although the coordination of these groups sometimes presented awkward problems, vitascopes served as the principal purveyors of moving pictures in the United States throughout the summer of 1896. The number of available machines, the comparative variety of films, the Edison name, and the hard work of the states rights owners assured a rapid, nationwide diffusion of this novelty.

Raft & Gammon's principal commercial strategies worked on two levels. First, they sought an immediate windfall by selling off the exclusive exhibition rights for specific territories (known as "states rights") to entrepreneurs, with publicity generating interest and raising the price. The sale of rights then bound these investors to the Vitascope enterprise. As Raft explained to Armat, "After

our territory is once sold, we need have but little fear about future business. After the purchasers of territory have their money invested, nothing will prevent their going ahead, and they will co-operate with us against all possible competitors and against untoward conditions and circumstances."[48] Thus, long-term profits would be achieved by renting machines to the states rights owners for $25 to $50 per month and through the sale of films.

States rights was considered a particularly effective way to deal with the threat presented by competing machines. This long-term strategy, however, was premised on controlling the exhibition field through Armat's patents—on which applications had been made but not yet granted. At best, such aid was in the distant future. During the interim, the goodwill and cooperation of the Edison Manufacturing Company were crucial.

In a long, often redundant, letter to William Gilmore, Raff outlined those areas in which Edison Company assistance was sought: good workmanship in the manufacture of vitascopes, prompt service, easy access to a camera and operator, exclusive ownership of films that they financed (so continuing an already established arrangement), and a promise not to sabotage the Vitascope Company by marketing a competing machine.[49] Raff's deference of tone, his frequent reference to moral obligations, and his eagerness to share profits with Edison and Gilmore all underscore the Edison Company's crucial role. This obeisance must also be placed against the background of Edison's business dealings in the closely related phonograph industry where he had just (February 1896) forced the North American Phonograph Company into bankruptcy. The investors in the old company plus the various owners of states rights either folded or, as in the case of the Columbia Phonograph Company, lost the special benefits of their investment. Edison then replaced the defunct company with the new National Phonograph Company under his immediate ownership. As Robert Conot has remarked, such activities gave Edison the worst image in this associated industry.[50] Moreover, if Edison chose to assume direct control over the phonograph, why not over moving pictures? Raft & Gammon never explicitly asked this unsettling question in their correspondence, but it was obviously on their minds. Nor did they apparently receive any reassurances. For the moment, Edison cooperated because Raft & Gammon were extremely useful and served both his reputation and pocketbook. In the longer term, Edison self-interest would prevail.

In the end, vitascope rights were sold for virtually every state outside the Deep South. Owners of these states rights came from a variety of backgrounds. Many had exhibited the phonograph and/or kinetoscope and were anxious to continue a profitable association with Edison. Others had a background in electricity and were ready to continue their Edison association but move into the entertainment field. A few had either theatrical experience or been otherwise

William E. Gilmore.

active in the field of popular amusement. A significant number of the Vitascope entrepreneurs had no relevant background, however, but were small businessmen hoping to strike it rich on Edison's latest novelty.

States rights owners had several ways to make a return on their investment. Typically, owners acted as exhibitors, providing a selection of films, a projector, and an operator. This package was commonly offered to theaters for a fee, usually several hundred dollars a week. In other circumstances, these exhibitors either rented a vacant storefront and kept any profit above expenses or presented films at a hall and divided receipts with its manager. A few leased subterritories to amusement managers who wanted complete control over their shows. Several historians have offered useful overviews of the experiences of these "pioneers," but focusing on the activities of one group of individual entrepreneurs is another way to understand the opportunities and difficulties faced

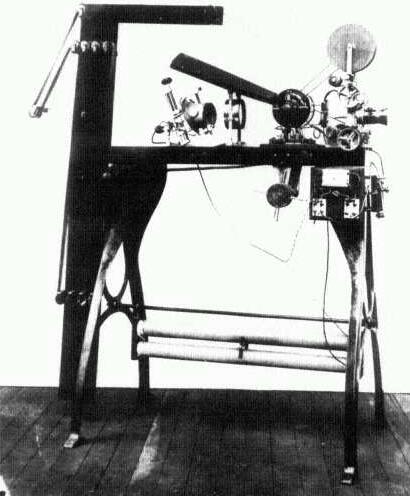

One of the first vitascopes.

by these early exhibitors.[51] What were their backgrounds? How did they come to acquire the rights? How did they try to exhibit this novelty and what kind of reception did it enjoy? The next section will address these questions by looking at the group based in Connellsville, Pennsylvania, with which Edwin Porter was deeply involved.

The Connellsville Entrepreneurs Acquire States Rights

As production on the vitascopes moved forward at the Edison works during March and April 1896, Raft & Gammon were busy promoting the machine and selling territories to entrepreneurs. Edwin Porter, then approaching the end of his naval enlistment and pursuing his interest in electricity, came in contact with this latest of Edison novelties. Perhaps seeing a demonstration in their office, he informed his friend Charles H. Balsley of this new invention and the commercial opportunities it seemed to offer. On March 30th, Raft & Gammon received two pieces of correspondence from Balsley asking about territory in Pennsylvania. The following day they responded, explaining that Pennsylvania had been sold and offering other territories.[52] Balsley's father, J. R. Balsley, and several other Connellsville merchants then decided to purchase the rights to the neighboring state of Ohio. A telegram on April 4th, however, informed the potential investors that Raft & Gammon had agreed to hold Ohio for "an interested party," Allen F. Rieser, who ultimately bought the rights.[53] Members of the consortium then traveled to New York and purchased the rights to Indiana for $4,000— an acquisition soon announced in the Connellsville newspaper[54] (see document no. 2).

DOCUMENT NO . 2 |

THEY OWN INDIANA |

The exclusive rights for the state of Indiana for the new Edison marvel, the Vitascope, have been secured by J. R. Balsley, R. S. Paine, F. E. Markell and Cyrus Echard of Connellsville. |

The vitascope is an improved kinetoscope by which moving life size figures of men, women and animals are thrown on a screen by means of bright lights and powerful lenses. A feature of the new machine which astonished the gentlemen named who recently witnessed a private exhibition in New York, for it is not ready for public view, was the almost entire absence of vibration in the pictures as they appear on the screens. The machine is said to be the wonder of the age. A vast money making field is opened up by it, as exhibitions can be given in theatres and halls, reproducing scenes and views with all the realism of life. |

The four Connellsville men struck while the iron was hot, and secured the exclusive territory of Indiana. No one can exhibit the machine in Indiana without first securing the right from the gentlemen who control that state. They will probably sell the rights by counties and cities and will doubtlessly realize handsomely on their investment. The vitascopes will not be sold, but remain the exclusive property of their maker, Raft and Gammon of New York, who will lease the machines for a nominal sum |

(Text box continued on next page)

monthly. This will enable purchasers of states rights to control their states absolutely. Messrs. Balsley, Paine, Markell and Echard have not disposed of any territory yet, but will place it on the market in a short time. There are great possibilities for the vitascope. The rights to Allegheny county, Pennsylvania were sold to Harry Davis by the syndicate for only $1,000 less than they paid [for] the rights for the whole state. There's money in it. |

SOURCE : Connellsville Courier , April 17, 1896. |

These four Connellsville men were, like many other Vitascope investors, small-time businessmen ready to risk hard-earned capital on the latest invention of America's folk hero Thomas Edison. J. R. Balsley had left the lumber business and retired to part-time inventing. In February 1896 he was selling a thread cutter and holder, "an ingenious little invention that everyone using spool thread will be glad to have."[55] Although Richard S. Paine, shoe store owner, had nearly gone bankrupt in the late 1870s and 1880s, he was prospering in the mid 1890s and owned stock in the local electric company.[56] He was ready to take another chance on the man who predicted the world would soon be run on electricity. F. E. Markell, a pharmacist with several drug stores, was prospering and six years later would become the first president of the Citizens National Bank.[57]

Appropriately, but coincidentally, a stereopticon lecture was given in Connellsville a few days after the group purchased their vitascope rights. As they were about to become entertainers, the local entrepreneurs surely attended. The program, called "The Secret of Success," illustrated the life and work of Thomas A. Edison and ended "in a grand concert by Edison's latest, loudest and best, the Auditorium Phonograph."[58] Certainly these small businessmen dreamed of succeeding on Edison's coattails.

Enthusiastic about their purchase, Paine and J. R. Balsley were ready to risk still more capital. Interest centered on several territories, particularly California, a state for which Raft & Gammon received many inquiries, including one from Thomas L. Tally, who operated a kinetoscope parlor in Los Angeles.[59] Having purchased Indiana, Balsley obtained a brief option on California. A telegram sent April 11th told him: "Price twenty-five hundred. Can hold till Monday no longer."[60] If Balsley was unwilling to invest additional capital, Paine seemed ready to buy the California rights alone. "We will be glad to let you have California if we can do so," Raff & Gammon wrote Paine on April 18th. "There are several parties after it and we have rather obliged ourselves to Mr. Balsley although we shall ask him to decide the matter today." A handwritten note at the bottom informed Paine that "Mr. B has taken Cala." and offered him other states as alternative investments,[61] but Paine was satisfied and the Connellsville entrepreneurs stopped there.

Balsley sent the down payment of $833.34 for California to Raft & Gammon on April 20th. It was acknowledged on the eve of the vitascope's premiere at Koster & Bial's:

You will find the receipt is in a little different form from the one given you on Indiana but we think you will agree with us that it is more specific and better for you. Since giving you a receipt on Indiana, we have adopted this regular form for all future sales of state rights as we want all receipts to be as uniform as possible.

We are promised fifteen machines on the 7th of May, and of that number we have put you down for one for Indiana. If we possibly can, we will save another for your use in California, but we cannot promise positively. However, we are confident that we can deliver you one or more machines before the first of June and possibly considerably before that date.

We note your remarks as to securing the Vitascope view of Coke Works, and we will probably make our arrangements to secure the same at the proper time. We thank you for your kind offer, and shall be glad to take advantage of it when the time comes.

The Edison Works have secured their first lot of what we call "clear stock" for films and we are counting on producing splendid results by use of the same. In fact, the outlook is very bright and we think the machine is going to create a sensation at our exhibit tomorrow night at Koster & Bial's.

Very truly yours,

Raft & Gammon

We enclose letters referring to California rights. Please return letters to us.[62]

As Raft had written to Edison's general manager, William Gilmore, the new contract made it clear that Raft & Gammon could not be held responsible for rival machines. It was this increased burden of risk that the Connellsville group found unsettling—particularly once amusement notices announced the imminent arrival of competing machines. Four days before the vitascope's debut, ads for Proctor's vaudeville organization reassured its patrons: "Coming very Soon to Proctor's Pleasure Palace—the Photo-Electric Sensation that all London is now flocking to see—The Kintographe."[63] Writing Raft & Gammon on April 25th, Paine worried about rival organizations and quoted a negative review of the vitascope's performance. Raft, with the Koster & Bial's premiere just behind them, countered with a reassuring and self-assured letter that offered to refund their money and sell the territory to another interested party. He dismissed potential competitors, insisting that "Information which we have received satisfies us, beyond doubt, that we not only have a superior machine but that we have such tremendous advantages over any similar machine that is now in existence or could be constructed hereafter, that there is but little [to] fear in way of competition." As Raft later added, "There never was a good, big-paying thing which has not been imitated."[64] Another letter of assurance was sent to J. R. Balsley two days later.[65] The Connellsville group wavered but decided to stay in.

The vitascopes being manufactured at the Edison works were not ready as quickly or in the quantity that Raft & Gammon had hoped for and led others to expect. On May 9th the completion of the first three or four machines was still a week away. Owning the rights to Illinois, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Maryland, P. W. Kiefaber was given two of these for an exhibition at Keith's in Boston. He insisted, with considerable justice, that two machines were necessary for a good show: certainly two were being used at Koster & Bial's.[66] The Boston premiere came on May 18th. On that same day, Paine and Charles Balsley also left Connellsville for New York to pick up their equipment and to learn how to operate the machine.[67] Within a week, other openings had occurred in Hartford, Philadelphia, and Atlantic City. The Connellsville consortium were forced to delay their debut, for they took their first projector to San Francisco, the cultural capital of the West, rather than to Indiana as originally planned. Gustave Walter had agreed to show the vitascope at his vaudeville theaters in San Francisco and Los Angeles. Porter remained behind in the New York area, waiting for his enlistment to run out.

Rival Novelties: the San Francisco Opening of the Vitascope

As Balsley and Paine were about to arrive in San Francisco, William Randolph Hearst's San Francisco Examiner devoted a full-page article to the Lathams' eidoloscope with its "Instantaneous Photographs of a Bull Fight." The article, profusely illustrated with line drawings based on film frames, informed readers that the bullfight "was arranged by Mr. Gray Latham for the purpose of taking Eidoloscope pictures now being thrown on the screen" in New York.[68] No equivalent coverage was devoted to the Connellsville entrepreneurs either before or during the vitascope's San Francisco debut. Its effect was to partially undermine perceptions of the vitascope as the original screen machine. Twelve days before the eidoloscope article, the Examiner had run a story on the vita-scope, but it focused on the predictions of Charles Frohman, one of the theater's leading impresarios, who sent road companies to San Francisco from his New York base. The vitascope, he believed, was "destined to substitute for stock scenery actual representations of scenes with all the human agents necessary, sitting, standing, moving about, chatting, in short, fulfilling the ordinary everyday duties and occupations of the ordinary individual."[69]

Once in San Francisco, Balsley and Paine encountered difficulties in setting up their machine—a common problem for the first vitascope showmen. In this instance, their lens gave too large an image for the distance from the Orpheum Theater's balcony to the screen and a new one had to be purchased from George Beck for $55.[70] There may have been further complications as well, for the New York Clipper listed the vitascope's West Coast debut as June 1st,[71] though it was not until June 7th that the local press, after many promises that the vita-

scope was coming, could announce the novelty's opening for the following day. In doing so the papers presented moving pictures as one of several novelties competing for the attention of vaudeville patrons. The Examiner informed its readers:

The Orpheum announces a strong string of novelties. Of these great stress is laid on the engagement of Edison's latest wonder, the vitascope. This wonderful machine, if it may be termed a machine, has been the sensation of the East for the past two months and has been secured by the Orpheum circuit at great expense, it is claimed. "Wizard" Edison has named the latest product of his remarkable genius the "vitascope" from the fact that it projects apparently living figures and scenes upon a screen or canvas before the audience. Another novelty announced is of a troop of Marimba players from Guatemala.[72]

Still other novelties like the dancer Papinta were holdovers from the previous week.

Balsley and Paine opened the vitascope on June 8th, projecting five films with an intermission of two minutes between each film.[73] Perhaps because San Franciscans had read such glowing reports of the machine's feats in New York, the novelty proved a mild disappointment. While declaring that the vitascope was "well worth seeing," the San Francisco Chronicle only gave it a brief two-line review.[74] Since most of the films had been or were available at Bacigalupi's Kinetoscope, Phonograph and Graphophone Arcade at 940 Market Street, the critic felt "the selection of pictures had not been the most interesting so far."[75] San Francisco clearly expected to see the best films available. Other newspapers did not feel compelled to comment on the machine's debut at any length. The Examiner reviewed the Orpheum's program only in passing. "The presentation of fine pictures by Edison's vitascope will be a pleasing feature of this week's program," it reported.[76] To most it did not seem to be the "Sensation of the 19th Century," as Walter suggested in his ads.

The blasé attitude that greeted the vitascope has to be understood in the context of rival novelties, particularly rival forms of screen entertainment, which converged on the West Coast during the spring of 1896. Alexander Black's picture play Miss Jerry , a "novel form of entertainment," had its debut in San Francisco on June 8th at the Metropolitan Temple.[77] It presented an entire play on the screen using a large number of photographic slides that followed each other in rapid succession. Dialogue for the various roles was mimicked by a narrator, in this case Miss Carrie Louis Ray. The San Francisco Call described the picture play as "a most exquisite treat."[78] A lengthy review in the Chronicle was more impressed with Black's picture play than with the vitascope, to which it was indirectly compared. "The photographer has done his work so admirably that it only needs a bit of imagination to make it all seem real, even to a nineteenth century audience. The idea is from Edison, but the love story is so

daintily and prettily told and so full of humor withal that it would be a captious audience that was not pleased."[79]

The illustrated song was yet another novelty. Lantern slides, projected onto the screen, offered a visual interpretation of the song's lyrics as they were performed. On the day the Examiner announced the vitascope opening, it ran a half-page article on the illustrated song calling it "the Latest Novelty of the Stage." After excerpting a song and describing the slides that accompanied it, the newspaper concluded with a brief quote from the proprietor of a vaudeville theater:

The day for ordinary ballad and sentimental singers on the vaudeville stage is rapidly passing away. Recent advancements along electrical and photographic lines have added so much to the pictorial advantages of the stage that the camera has been brought into active requisition in this particular. During the past few months pictures instinct with life, vivid with color and clear in characterization have been associated with a song so that while the verbal description and harmony come from the throat of a singer, the eye is satisfied with the mimic portrayal of the scene. Not only does the song thus presented gain at least 50% in the estimation of the audience, but it also enhances the salary of the singer in equal proportions.[80]

At approximately the same time, moving pictures, the picture play, and the illustrated song jointly refocused the public's attention on the entertainment possibilities of projected images. Only during the course of time was it to become apparent that moving pictures were to dominate the commercial screen to the virtual exclusion of other formats.

The greatest photographic novelty during much of 1896 was not moving pictures but the x-ray. This newest discovery received constant newspaper attention between March and June, with Hearst's Examiner featuring stories in which bullets embedded in Civil War veterans were discovered after thirty years of unsuccessful probing. Edison himself received considerable front-page attention as he worked on "perfecting the x-ray."[81] Americans were even more impressed by the ability to reveal something no one could see than to capture and "reproduce" what could be seen every day. The vitascope, viewed as the logical extension of Edison's peep-show machine, was outclassed by this impressive scientific discovery.

Despite initial disappointment with the vitascope, the Chronicle reassured its readers that subjects closer to their initial expectations were to be offered during the second week: "There are many films coming and the sensational one of the Wave, which has been so much written about, will be worth seeing especially."[82] The following week Sea Waves (i.e., Rough Sea at Dover ) was heartily praised: "Those who have not seen the wave should see it. It is such a thrilling realistic thing that the people in the front seats involuntarily get up afraid they will get wet."[83] Since James Corbett was about to fight Tom Sharkey

in San Francisco on June 24th and since Corbett was the home-town hero, The Corbett-Courtney Fight was added during the second week as a timely subject with hometown appeal.[84] Boxing fans were able to examine their hero's technique with a life-sized image, and Corbett dropped by to watch himself fight.[85] This coup, however, had to compete with the x-ray. On June 18th, the world boxing champion "submitted to the most searching of all photographic processes for the first time in his life and when it was over Corbett said that the experience had been both interesting and enjoyable." After examining various parts of his skeletal structure, Dr. Phillip Jones made an x-ray of his right forearm—a process that took twenty minutes. The result was then published in the Examiner .[86] Once again the vitascope had been preempted by a rival novelty.

The vitascope's third week at the San Francisco Orpheum featured The May Irwin Kiss , which finally reached the West Coast two months after it had been taken. While the response at the Orpheum was not reported in the press, the film was given an enthusiastic reception almost everywhere. According to one review, "the hit of the show, so far as marvellous lifelike effects and mirthful results with the audience go, was the amusing, much-prepared-for kiss—the May Irwin kiss from the 'The Widow Jones.' In this the effect was wonderful. The figures were so large that one could almost tell by the motion of the lips what Rice was saying to May Irwin and what Miss Irwin was replying. The facial expression was the widow to a T, and ditto Rice, and the real scene itself never excited more amusement than did its vitascopic presentment, and that is saying much."[87] In the middle of the third week, it was announced that "new views have arrived for the vitascope and this week will be the last one that the wonderful work of this machine will be seen."[88] The vitascope's run ended on a happier note than it began.

The vitascope was a "novelty"—a term applied to oddities, scientific innovations, ingenious demonstrations of strength and coordination, or displays of beauty and sexual allure with which vaudeville managers tried to amuse their patrons. Shortly after the vitascope's departure, the Chronicle remarked, "Vaudeville novelties are appearing in such rapid succession at the Orpheum that it would seem as if the supply must soon be exhausted. Papinta, the vita-scope, Black Patti, Blondi and Macart's dog and monkey circus have all appeared in rapid succession and now comes another novelty in the way of Herr Techow's cat show, which by reason of its oddity ought to attract attention."[89]

The importance attached to novelty was particularly significant at this moment in American history. The United States was coming out of a major depression (the one that had bankrupted Porter's tailoring establishment), spurred on by the introduction or successful commercialization of a wide array of products and technical improvements: the automobile, the phonograph, electric trollies, and electric light—as well as cinema. This emphasis on novelty celebrated

innovation and the changes transforming American life. Vaudeville confronted this transformation and often expressed it by emphasizing not only novelty but variety. As one journalist explained,

To those interested in the secret of the great success of vaudeville upon the stage, it must be obvious that the clue to the whole thing lies in the nervousness and desire for change that is characteristic of nineteenth century mankind. Sitting in a theatre for three hours at a stretch, looking at the same faces, hearing the same voices and waiting for the denouement of a play, is apt to become monotonous to most people. They prefer a constant change, both of actors and acts, and this they get in a theatre where vaudeville is presented.[90]

From this perspective, the vitascope was the vaudeville novelty of the nineteenth century, for cinema was to transform America's cultural life in the years ahead.

Despite its need for novelty, popular culture also relied on familiarity. Late nineteenth-century theater, particularly as it was performed in America's small towns, brought back the same plays year after year to be seen by the same audiences. In vaudeville successful acts were held over so that the spectators could see them again the following week and experience the same pleasure. Vaudeville acts themselves were rigorously defined by categories that were repeated over the course of time in an almost ritualistic formula.[91] The obverse side of variety was repetition. The acceptance of repetition can be seen in the projection strategies adopted for the vitascope, with its film loops, and in the exhibition of both new films and holdovers. It is also evident in the redundancy of subject matter that immediately followed the first films. A myriad of "kiss films" followed the Irwin/Rice novelty. Given the cultural framework in which they were shown, it would be too easy for the cultural historian simply to dismiss these imitations as derivative. Vaudeville and the vitascope valorized tradition and continuity as well as change and innovation.

Porter Joins His Connellsville Friends in Los Angeles

Porter was discharged from the navy on June 18, 1896.[92] Later he testified that his career as a motion picture operator began in June 1896, and he may have stayed briefly in New York City to operate the vitascope at Koster & Bial's.[93] At the end of the month, he was in Connellsville, but he soon "went to California to operate the first Vitascope machine exhibited there."[94] If the former naval electrician left Connellsville quickly, he could have reached Los Angeles just as the vitascope was opening at Walter's Orpheum Theater in that town.

After a week's hiatus while Balsley and Paine moved from San Francisco to Los Angeles, the Connellsville entrepreneurs resumed their film projections on

July 6th. The Los Angeles Times heralded the machine's imminent debut with enthusiasm greatly exceeding that of the San Francisco press:

The vitascope is coming to town. It is safe to predict that when it is set up at the Orpheum and set a-going, it will cause a sensation as the city has not known for many a long day.

The vitascope is Edison's latest and most shining triumph. It is a miracle of human ingenuity in the realms of electricity and photography. It is on the same order as the kinetoscope, with the difference that in the kinetoscope one person at a time peeps into a hole and sees a tiny moving picture while in the vitascope, the picture is thrown upon a screen and shines forth. . . life-size, so that the entire audience can see the picture at once. The vitascope was first publicly exhibited only about two months and a half ago.

The things shown by the vitascope are of many different kinds. A bit of Broadway in New York is very striking. The audience can see the swarms of people hurrying along, the jostle of horses, carriages, trucks, etc., in the street, all moving and changing and so real one almost expects to hear the street noises. A snowstorm, a skirt dance and a sea beach scene are some of the things shown. The life-like reality of the pictures is said to be startling. In San Francisco and elsewhere, one of the most popular scenes was a reproduction of the famous bit of acting in which May Irwin is kissed by John C. Rush [sic ]. The changing expression of their faces, their graceful movements, the play of hand and lip and eye, are said to be faultlessly reproduced.[95]

The Los Angeles Herald felt it necessary to describe the novelty and how it worked, suggesting that Balsley, Porter, and Paine were the first to project moving pictures in the city that was to become the center of the film industry.[96]

Once again there were competing novelties. Miss Jerry opened on the same night, this time at the Los Angeles Theater. Inquiries for tickets to Black's picture play indicated that "any novelty will take well in Los Angeles."[97] Another "novelty" reported in a Herald article ran opposite the paper's blurb on the vitascope: a French scientist claimed that thoughts could be photographed.[98] In this context, projected moving pictures did not seem quite so "marvelous." Anything, however extraordinary, now seemed possible. As the Los Angeles Herald was to comment on the vitascope, "Can genius go farther? We have been made to hear the voices of our distant friends and now we are enabled to see them move and act. Truly it is enough to make Franklin turn in his grave with wonder of it and yet, so attuned are we to the marvelous in this day and age of the world that we are scarcely decently surprised."[99] Nevertheless, the vitascope headlined one of the Los Angeles Orpheum's best programs in its three-year history.

News of the vitascope's arrival had packed the 1,311-seat Orpheum.[100]

Every seat in the theatre was sold ere the box office window was opened for the evening's business. Standing room only was sold, and the purchasers of it formed a fresco around the entire circuit of the walls from box to box in addition to which some hundreds who applied for seats left, to come again later in the week. So much for what

was expected of the management, and it can be said but in a few words, the immense audience was not disappointed.[101]

The Los Angeles Times provided readers with a clear description of the show's format, the protracted screening of the "endless band" of film and the interruptions that occurred while these films were changed:

The theatre was darkened until it was as black as mid-night. Suddenly a strange whirling sound was heard. Upon a huge white sheet flashed forth the figure of Anna Belle Sun [sic ], whirling through the mazes of the serpentine dance. She swayed and nodded and tripped it lightly, the filmy draperies rising and falling and floating this way and that, all reproduced with startling reality, and the whole without a break except that now and then one could see swift electric sparks. Then the picture changed from the grey of a photograph to the color of life and next came the fairy-like butterfly dance. Then, without warning, darkness and the roar of applause that shook the theatre; and knew no pause till the next picture was flashed on the screen. This was long, lanky Uncle Sam who was defending Venezuela from fat little John Bull, and forcing the bully to his knees. Next came a representation of Herald Square in New York with streetcars and vans moving up and down, then Cissy Fitzgerald's dance and last of all a representation of the way May Irwin and John C. Rice kiss. Their smiles and glances and expressive gestures and the final joyous, overpowering, luscious osculation was repeated again and again, while the audience fairly shrieked and howled approval. The vitascope is a wonder, a marvel, an outstanding example of human ingenuity, and it had an instantaneous success on this, its first exhibition in Los Angeles. A representation of Niagara Falls is now on its way [from the] East, where it was first exhibited only two weeks ago, and this will be added to the bill on Thursday evening.[102]

The opening night performance suffered from minor deficiencies, which were probably owing to inadequate power, since the Connellsville group was running its machine on batteries, an uncommon practice at the time.[103] The vitascope, unlike traditional magic lanterns or the Lumières' cinématographe, ran on electricity, which often created problems. The first vitascope exhibition in Worcester, Massachusetts, for example, was marred by electrical problems. As a result, "Cissy Fitzgerald's wink was invisible owing to insufficient speed and light, and the boxers struck with dreamy sluggishness."[104] Here Porter's background as an electrician and telegraph operator provided expertise that could correct the problem. After one critic returned to the Orpheum, he was able to report that the vitascope "scored even a greater success than on its first appearance, for there had been time to remedy all slight defects caused by the hurry in which it had been necessary to set it up."[105]

The vitascope program at the Los Angeles Orpheum was changed in midweek and reviewed the following day:

The announced change of programme of the Vitascope at the Orpheum last evening was well received, though some of the plates [sic ] which had just arrived from New

York were broken in transit and could not be presented. The view of the whirlpool rapids of Niagara Falls was a most realistic picture showing the rushing, roaring, whirling foam-beaten waves and splashing spray true to nature. Another view presented was that of the Atlantic Ocean beaches rolling up to the shore in the vivid way peculiar to the breakers of that turbulent pond. The picture of the female equilibrist doing a difficult act was appreciated, but the sympathies of the audience went out to the two performers in the kissing scene, and the graceful woman who danced in skirts.[106]

During the first week of moving pictures, at least 20,000 attended the Orpheum, while as many as 10,000 others were turned away. This encouraged the theater to plan a Sunday matinee.[107] Suggesting the city's enthusiasm for the novelty, a Los Angeles Times reporter speculated on the vitascope's future. "Wonderful as it is, the vitascope is as yet surely in its infancy," he wrote. "It is hard to say to what proportions it may yet be used in the amusement field 'with the development of color photography and the combining together of the vitascope and the phonograph, both of which are probably not so very far away."[108]

The most successful films shown on the vitascope were those that isolated a specific characteristic or representational technique to achieve a novel effect: the close view of a kiss, the forward-moving wave assaulting the spectator, even scenes of busy street life "vitascopicly" presented inside a theater (breaking down the separation of indoors and outside). These images were non-narrative, pure examples of what Tom Gunning has called the cinema of attractions.[109]The May Irwin Kiss , for example, was excerpted from a musical, but audiences did not need to know the story or the situation in which the kiss occurred to enjoy the film. In fact, as we shall see, the film could easily be attributed to an entirely different play. With the couple placed against a black background, the kiss was isolated in time and space. Even to the extent that the kiss had a beginning, middle, and end, this progression was undermined by the scene's rapid repetition during the exhibition process. Films like the wave were particularly effective when shown as loops, the repetition of the scene mirroring the repetitive nature of the ocean waves breaking on the shore. In the process these loops drained the image of temporal and spatial meaning.

During the second week, Porter and his associates offered another set of films. "The vitascope came last and the audience applauded every one of the magic pictures rapturously," reported the Los Angeles Times . "The new pictures were Amy Fuller's famous skirt dance, ending with a hand spring; a picture of three pickaninnies, patting, juba and cutting up capers, and a weird Oriental thing, 'the India short stick dance' in which half a dozen natives figure."[110] Ending their Orpheum engagement after the second week, Balsley, Paine, and Porter had toured the California vaudeville circuit as it then existed. Their options were limited by their dependency on electricity. As another vitascope exhibitor wrote Raff & Gammon, "To enable us to make money we have to so remodel the machine that it can be worked with hand power when we cannot

Tally's Phonograph Parlor on Spring Street in the summer of 1896.

get electricity and construct new travelling cases so that the breakable parts can be safely and rapidly packed for shipment. I believe there is plenty of business to be obtained in the country once we are prepared to work it, but it is worse than folly undertaking it in our small towns until we are ready to meet a three night's business and then pack up and get out to the next town."[111] Visits to California's smaller cities and towns were neither practical nor financially justified, particularly in the middle of the summer.

After the Orpheum run was over, R. S. Paine returned to Connellsville, leaving Porter and Charles Balsley to manage the machine. The two friends stayed in Los Angeles and reopened their show at Tally's Phonograph and Kinetoscope Parlor. Tally, who was eventually to become a major West Coast exhibitor and an important executive at First National during the late 1910s and early 1920s, promoted his move into cinema with blurbs in the local papers:

Tonight at Tally's Phonograph Parlor, 311 South Spring St, for the first time in Los Angeles, the great Corbett and Courthey prize fight will be reproduced upon a great screen through the medium of this great and marvelous invention. The men will be seen on the stage, life size, and every movement made by them in this great fight will be reproduced as seen in actual life.

New York and London went wild over this wonderful invention and last week the Orpheum was packed to the walls with people anxious to see the wizard's greatest wonder, the vitascope. Come tonight and see the great Corbett fight. From this date on the fight will be exhibited every evening.[112]

Tally's Phonograph Parlor as it would appear in 1898.

Thomas Tally appears behind the kinetoscopes.

The next day it was reported that "great crowds flocked to see the greatest wonder of the world, the vitascope, Mr. Edison's latest invention. Performances will be given regularly every afternoon and evening and the programme will be changed daily."[113] Admission was ten cents. After a successful run, the Connellsville entrepreneurs sold their rights for California to Tally and returned home. Tally's machine was destroyed by fire shortly thereafter—or so, at least, it was said—perhaps as a way for Tally to free himself from any royalty requirements.[114]

The Vitascope Faces Increasing Difficulties

Purchasers of vitascope exhibition rights faced steadily rising competition throughout the United States. Gray Latham surreptitiously examined the vita-scope at Koster & Bial's and added an intermittent mechanism to the eidoloscope.[115] The Lathams' improved machine then opened at Hammerstein's Olympia in New York City on May 11th and had a successful five-week run. Subjects included Whirlpool Rapids, Niagara Falls; Fifth Avenue, Easter Sunday Morning ; and Bullfight . All "were excellently produced and won storms of applause."[116] During July they were "hot competition" for the vitascope in

Atlantic City.[117] By mid May, C. Francis Jenkins had found a backer for his phantoscope—the Columbia Phonograph Company—and was beginning to market his machine.

The Lumière cinématographe premiered at Keith's Union Square Theater in New York City on June 29th. It was soon evident that "nothing has ever before taken so strong and lasting a hold on the patrons of this house as the cinematographe."[118] Although only three cinématographes were in the United States by mid August, thereafter Lumière machines arrived from France with greater rapidity. Since the cinématographe did not use an endless band, people had to return to the theater to see the same subject again. Relying less on the mere novelty of lifelike images than vitascope entrepreneurs, the cinémato-graphe operators were beginning to explore ways to sequence films as early as July, when they showed various scenes of the coronation of the czar and czarina in Russia.[119] A less well known competitor was the kineopticon, which played at Tony Pastor's theater in New York City from late August to mid October. Among its European views were Paris Street Scenes, Boxing Kangaroo , and Persimmons Winning the Derby .[120] The vitascope's "monopoly" was challenged by an array of competing machines, many of which were technically equal or superior to Armat's projector. The only way for Raff & Gammon to block them effectively was through court action based on patent infringement. This was impossible since Armat's disputed patent applications had not yet been granted. Competition was a reality that the vitascope entrepreneurs had to endure from the outset.

Despite Raft & Gammon's best efforts, vitascope entrepreneurs faced many difficulties.[121] In Canada the Hollands could only give vitascope exhibitions in Toronto and Montreal, where the cinématographe and eidoloscope provided direct competition.[122] The Edison Manufacturing Company was also producing films of poor technical quality. The raw stock used during the summer was still manufactured by the Blair company. Although Blair's semi-opaque product had been excellent, the emulsion peeled away from the base of its clear stock.[123] "I enclose you a sample of a film 'Herald Square', that has been run through just seven times. We have at least six films (amongst them 'Annabelle') in as bad a condition," wrote an unhappy Andrew Holland. "It simply means that we are working for the [Edison] Laboratory—paying our own expenses and doing the chores for nothing. For my part, I would rather pitch the business to the dogs than to continue it under such circumstances."[124] The films' photographic quality was often poor, too. Edmund McLoughlin, who owned the rights to most of New York State, was unhappy that his films were "very gray" and discussed the problem with people at the Eastman Kodak Company. They suggested that Edison was not using the proper emulsion.[125] In mid September the Edison Manufacturing Company shifted its purchases of film stock from the Blair Camera Company to Eastman, inaugurating a customer-supplier relationship that

was to endure for many years.[126] The Edison Company, however, was not as quick to correct these failings as Raft & Gammon and the vitascope owners would have liked. The problem of quality was further exacerbated by the high price of Edison goods, which gave the inventor a healthy profit but left the states rights owners unremunerated.

Owners of exhibition rights felt their efforts were often compromised by a shortage of new, exciting subjects—particularly when competing against rival machines. Kiefaber demanded "good humorous, startling features to keep public turned towards us; with good live scenes we can keep our people attached to us."[127] This need was underscorw the Lumière organization arrived with a large backlog of subjects, all unfamiliar to American audiences. Keith manager E. F. Albee only reinforced this impression when he complained to Kiefaber that "the last two weeks, the films have been of such poor material and the views so indistinct that instead of the machine being a feature, it has become a farce."[128] But subject matter and technical excellence were not the only factors at play. Since Keith had acquired the American rights to the Lumière machine for the first months of its exhibition in the United States, it was inevitable that the cinématographe supplanted Kiefaber's vitascope at Keith's Boston and Philadelphia theaters.