The Porter/Edison Films in Disfavor

As Edison executives were seeking to secure their commercial future through license-related agreements, Edison films were frequently and stridently criticized for their failure to present clear, enjoyable, and effective narratives. The New York Dramatic Mirror , which championed the storytelling methods of Griffith, felt that The Lovers' Telegraph Code (Porter, November 1908) contained "the foundations for a capital comedy . . . although the full possibilities of the situation appear to have been overlooked or awkwardly handled in the construction."[56]Miss Sherlock Holmes (Porter, November 1908) was "an inconsistent and complex story, none too easy to follow, although it is admirably mounted and fairly acted."[57]The Old Maids' Temperance Club (Porter, November 1908) started out "in promising style" but became "flat."[58] One of the most devastating reviews was directed at The Tale the Ticker Told (Dawley and Armitage, December 1908):

This film is a confused, unintelligible series of scenes in which a will, an heir and an heiress, two rivals for a woman's hand, a hunting trip, a bad broker and a good broker, a trip in automobile down Broadway, a scene in the Stock Exchange and a suicide in a broker's office are so mixed up without connection or reason that we can make little headway in figuring out what it is all about. Somehow we divine that one of the rivals puts up a job on the other, gets the worst of it and kills himself. The photography is all right and the scenic qualities are fine, but the story is in an unknown picture language and if one can't understand the story what is the use of all the acting? The tale that this ticker told needs translation.[59]

A Persistent Suitor (Porter, December 1908) "would have been infinitely more humorous if it had been logically and consistently constructed, and if many opportunities for comedy had not been overlooked or carelessly handled."[60]

Positive reviews reiterated the Edison films' usual basic weaknesses by noting

their absence. With An Unexpected Santa Claus (Porter, December 1908), "The Edison Company continues to produce films that are clearly told picture stories, in pleasing contrast to a number issued from the same studio last fall."[61] For Turning Over a New Leaf (Dawley and Armitage, December 1908), Armitage's "camera has been placed closer to the actors than was formerly the Edison practice, thus making identity of the different characters more apparent to the spectators."[62]Where Is My Wandering Boy To-night? (Dawley and Armitage, January 1909)

comes as near to the point of perfection in every essential particular as any subject ever produced by an American company. It lacks every fault that has been apparent heretofore in so many Edison productions. The story, the first and most important consideration in every picture, is simple, consistent and interesting though trite. The characters are introduced distinctly, and their identity is clearly maintained throughout. The scenes follow each other naturally and each tells its part of the story and no more. The acting is done with great feeling, but without being overdrawn. There is not a gesture or movement that appears to be wanting and there is not one too many. The photography is even, and the camera is placed sufficiently close to the actors to make each character always recognizable. Finally the scenic backgrounds are in the usual artistic taste of Edison pictures. In short, the picture is a model that the Edison forces would do well to follow in future work.[63]

This flurry of positive reviews suggests that the Edison films had been bad enough for the Mirror critic to mute many previous criticisms. Certainly this was the case with Moving Picture World , which was careful not to criticize the Edison Company's productions lest its executives withdraw their advertising—along with the advertising of affiliated licensees—as they had done once before.

Edison executives were frustrated by the quality' of their films and wanted to find more qualified personnel. In a letter to the managing director of the Edison Manufacturing Company in Europe, Thomas Graf, Frank Dyer confessed:

In our moving picture business we are very badly handicapped for the lack of skilled camera operators and stage directors. The business has developed to such enormous proportions that it seems to be very difficult to get a good man. Camera men may be found, but to get a good competent stage director, a man with sufficient originality to get up and direct the acting of a picture, seems to be almost hopeless. This is especially true in the case of trick and eccentric pictures. It occurs to me that such a man might be found in Paris, either out of employment or who might be willing to take a better position in this country. The leading manufacturers are there and they must have educated a good many men. I would like to get a first-class man in every respect, one of good intelligence, full of ideas and capable of having them worked out, and especially a man familiar with getting up trick pictures and startling and original effects. For a really good man we could pay $75.00 per week and traveling expenses from

By 1909 film dryers at the Orange, New Jersey, plant had

gotten larger to handle increased capacity.

Paris, with a guarantee to pay expenses back if unsatisfactory. . . . Time is very essential, as we are being handicapped every day by this defect.[64]

Dyer's letter reveals the depths of his unhappiness and his limited insights into the problem. Like Porter, he did not recognize that the crucial problem involved the construction of narratives that could be readily understood by the spectator.

The commercial basis for Dyer's unhappiness is evident in the superficially impressive figures for film sales during the 1908 business year. Film sales increased 170 percent over the previous business year, from $205,243 to $554,359; profits, however, only increased 97 percent to $230,383. This occurred because the number of productions completed between February 1, 1908, and January 31, 1909—seventy-four in all—quadrupled (increasing expenses), even as the number of prints sold on a per-film basis fell sharply, particularly late in the year as quality declined and the number of films offered by competitors increased.

Dyer and Wilson, unable to locate a foreign director who would solve their production problems, reorganized the Kinetograph Department in January 1909. Porter ceased to make his own productions by mid month and continued

solely as studio manager and head of negative production.[65] Dawley, given a raise to $45, began to make $5 more per week than Armitage. Harry C. Matthews was hired as a stage director at $40 per week and teamed with Henry Cronjager ($25 per week). The director and cameraman no longer received identical wages—an indication that competent directors were not only harder to find but that they were assuming principal responsibility for productions. These two units were based at the Bronx studio, while a third unit was formed (for which George Harrington, William Moulton, and Henry Schneider were hired) and sent to the Twenty-first Street studio to make short comedies.[66] Porter was thus put in a strictly management position.

Dyer introduced a director/unit system of production. The cameraman no longer worked with the stage director but for the film director. There was nothing automatic about this shift. Although the photographer and stage director had different responsibilities, they could have easily retained co-equal status. And yet, the director needed to be in closer consultation with the studio head than the cameraman. Story and script, actors and sets—all the "non-filmic" elements—were his responsibility. We know, for example, that Porter collaborated with Dawley on the script for The Star of Bethlehem (March 1909). The move to a multi-unit production system with a supervising producer thus encouraged the emergence of the director as unit head. An efficiently run studio with a well-established hierarchy as well as clear lines of authority and accountability required the implementation of the director system.

The reorganization of production occurring in the industry at this time was primarily a move from the collaborative system to a director-unit system rather than, as Janet Staiger has suggested, from a cameraman system to a director system.[67] Such a shift had occurred at Vitagraph early in 1907, where there were three collaborative teams: J. Stuart Blackton, Albert E. Smith, and Jim French (their senior employee) each acted as cameraman for one of the units and worked closely with stage directors (including William Ranous). A reorganization took place when Smith left for Europe. French was charged with managing the studio operations. Blackton assumed the role of production head and oversaw the work of the three directors, and the three directors had cameramen in their charge. The shift to a director-unit system came about because a military-type model of command facilitated the management of a large and growing studio.

The shift at Vitagraph gives us insight into the transition occurring two years later at Edison's Bronx studio. While documentation is scanty, the Edison Company was in the midst of a tortuous transitional phase: the director-unit system was emerging but not yet fully established. Moreover, Porter, who felt awkward handling actors, was not adept at giving orders and delegating authority, a necessity for any manager who hoped to run a multi-unit studio successfully. In short, he was still committed to a collaborative mode of work. Moreover, he

was unhappy with the frenetic pace of production necessitated by the mass entertainment system. The studio manager "always believed that the bane of the producer was the turning loose of so many reels a week, on certain days, regardless entirely of surrounding circumstances." This did not allow "sufficient time to do those things which ought to be done and to avoid those things which ought not to be done."[68]

The extent of this shift to the director-unit system can easily be exaggerated. The cameraman retained a large amount of authority. He developed the negative and still edited the picture. On the other hand, the increased rate of production resulted in the creation of a script department. In late January 1909 Stanner E. V. Taylor, who had scripted Griffith's The Adventures of Dollie , was hired at $35 a week to form it. While Alex T. Moore remained as manager of the Kinetograph Department (still making $100 per week), he was increasingly squeezed between Porter on one hand and Wilson on the other. Negative film production, of course, was only one of many departments under Wilson. These also included equipment manufacturing, the production of release prints, and sales.

While Porter concentrated on his job as studio head, Edison films continued to be greeted with frequent complaints. A few films received mild praise, but most were strongly criticized. Drawing the Color Line (January 1909) "is very well carried out, although it might have been made stronger if the different situations had been properly led up to."[69]Pagan and Christian (Dawley, January 1909) was "a beautifully elaborate production that may find more popularity in lecture course entertainments than in regular picture houses." Made at the height of the censorship crisis in New York City, the film dealt with a commendable theme, but "the story is somewhat obscure in its details and drags in the action."[70]A Bachelor's Supper (Dawley, February 1909) was criticized for "the unnatural manner in which the story is worked out."[71]The Saleslady's Matinee Idol (Dawley, February 1909) was condemned because "the producers do not appear to have realized the value of their best scenes—at least they have failed to make the most of them and have introduced other scenes that are either confusing or inconsistent." The critic again emphasized the absence of effective intercutting: "If short scenes had alternated back and forth between the stage and the balcony, showing the progress on the stage and the effect on the balcony audience concurrently, the effect would have been greatly increased."[72] This is precisely what Griffith did in A Drunkard's Reformation , which he began to film a few days after this review appeared.

The criticisms leveled at the Edison films were applied to productions by other companies as well. After listing several specific failings in a potentially excellent production, a review of Selig's Love and Law concluded, "A few titles would have cleared up some of the obscurity, but care in construction, to make sure that the story would be conveyed easily to all spectators, would have been

better."[73] With The Castaways , Vitagraph was chided because "the scenes of the story are disconnected and give the impression of being hastily strung together."[74] Many films, however, received a positive response. Biograph continued to enjoy the most frequent kudos, but Woods often praised subjects like Kalem's The Girl at the Mill and used them to illustrate his points—in this instance that "it is the simple, uncomplicated story, if well told, that gives the best results in moving pictures."[75]

The dissatisfaction with Edison productions came from many quarters. In early February, Jonathan M. Bradlet, who had written several scenarios for the Edison Company, wrote Frank Dyer a polite letter outlining a few criticisms of specific films:

It appears to me, that in several of your productions, the studio does not pay enough attention to the distribution of the light. For instance in "KING'S PARDON "the top light is entirely too strong, it is difficult to see the features of the Judge sitting at the high bench, while the faces of the other persons, sitting below the Judge, in a less strong light, are visible.

Your studio grows a little careless in the details, for instance, in "UNDER THE NORTHERN SKIES " the supposed murdered man is a too willing corpse. He steadies himself on his legs and gently passes his arm over the shoulders of the man carrying him away.

You would be surprised to see how the spectators pay some attention to these little details. When a man is supposed to be dead, they want him to appear dead and not to help himself.

With these two cases you can ask Mr. Porter to put more care.[76]

In a postscript to his letter, Bradlet voiced sympathy for Porter's predicament. "I do not blame Mr. Porter but the foolish exhibitors refusing to show repeaters and forcing the Manufacturers to produce too much," explained Bradlet. "If repeaters could be shown you would sell more copies; as there would not be such a tremendous demand for new subjects, the producers would have more time to take care of the details of the new productions." But other companies operated under the same constraints with better success. When an Edison sales representative went on a business trip, he wrote the home office, "I can sell machines but film is out of the question. Our films are being roasted everywhere, particularly the short subjects at 21st St Studio and you know they are not what they should be."[77]

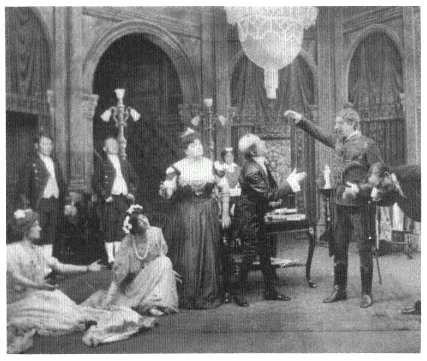

By late February, Edison executives were thoroughly disenchanted with Porter and the films he was producing. Some of these faults can be seen in a surviving fragment of The Uplifting of Mr. Barker (Dawley, February 1909).[78] The actors are heavily made up and their exaggerated gestures often have no clear meaning. This acting style may have been encouraged by a distant camera that reduced the actors to quite small proportions in the frame. The sets and actors are presented frontally, the lighting is fiat and the performers seem more like cartoon characters than real people. Scenes are often drawn out. Even the

The Uplifting of Mr. Barker.

surviving fragment supports the Dramatic Mirror's suggestion that "a pair of shears judiciously used on the film would have improved it."[79] In one scene at a society ball, Mr. Barker fights with his daughters' two escorts and pushes them into a fountain. How this comes about is unclear and there is a long exchange between the three that is impossible to decipher even after repeated viewings. The Mirror's critic may have been generous when he said the film is "funny only in spots."[80]

Films that were completed but not yet released would receive even more negative assessments. The Landlady's Portrait (Matthews, February 1909) was "a mixed-up 'comic' without point or story and we must confess our inability to find in it a single excuse for a laugh."[81]A Bird in a Gilded Cage (Matthews, February 1909) was "greatly weakened by faulty construction, aimless action and the omission of necessary connecting scenes or subtitle."[82]The Colored Stenographer (Matthews, February 1909) was condemned because "there is in this subject so much aimless action, having no apparent connection with the story, that a really good comedy idea is obscured and weakened. We can liken it only to a writer who starts out to tell a certain tale and who continually

digresses to tell little side stories of no interest, and only calculated to draw attention away from the main issue."[83]Mary Jane's Lovers (Matthews, February 1909) was "another good comedy idea weakened by bad handling."[84]A Midnight Supper (Matthews, February 1909) was "certainly not the kind of work the Edison company should be offering to the public," and Love is Blind (Matthews, February 1909) was "not much better handled" and "whatever point there is to the subject is lost in the hurried action."[85] Edison films were being constantly attacked for the incoherence of their narratives.