Edison and Biograph Begin To Negotiate

By June 1908 it was becoming clear that Edison and his licensees would be unable to drive the Biograph association from the field. Many film people, particularly exhibitors, viewed the rivalry as desirable. "It is well that there are two competing elements in the field," Moving Picture World asserted. "It simplifies the question of providing separate programs to theaters which are in close proximity to each other and it gives the manager the opportunity of making a distinct change if he is subjected to treatment which is injurious to his business."[1] The Association of Edison Licensees had eliminated little competition. Although it had forced a few renters to abandon their aspirations to become producers, the organization had failed to exclude unlicensed European

producers from the marketplace. The warfare between Edison and Biograph had even provided a space where some new producers—for example, the Goodfellow Manufacturing Company and the New Jersey-based Centaur Film Company— could operate.[2]

The Edison-Biograph rivalry made discipline within the ranks of the Film Service Association difficult to enforce. Some theaters still rented programs through subletters and showed films by both associations—practices that had been forbidden. Exchanges undercut the rental rates with increasing frequency. In mid June, William Swanson informed Frank Dyer that two of the largest dealers in Chicago would withdraw from the association if action was not taken against violators of the agreement.[3] When Laemmle's income from his Evansville office fell from $1,000 to $500 per week, the renter asked Dyer to come up with a solution. Laemmle hinted that he would find his own solution if Dyer could not provide one.[4] Tally's Film Exchange in Los Angeles also threatened to go its own way.[5] If Edison interests could not eliminate their opposition, it was only a question of time before licensed producers and FSA exchanges broke off on their own.

Biograph and its licensees were also unhappy with the state of affairs. Unlike Edison, Biograph was not receiving royalties for its sponsorship of importers. Its goal was to survive and then work out a financial arrangement with Edison. The Kleine Optical Company encountered many expenses in opening up offices across the country, yet faced a restricted market for its goods. The litigation and commercial rivalry that had plagued the American industry for ten years continued unabated and seemed to hurt almost everyone. While in opposite camps, Pathé and Gaumont let both sides know that they were displeased with the state of affairs and urged a reconciliation.[6]

On July 11th, shortly after assuming charge of Edison's film business, Dyer lunched with Harry Marvin and Jeremiah J. Kennedy of Biograph and discussed peace terms.[7] A week later, George Kleine came to New York and met with the Edison vice-president.[8] By the end of the month, negotiations had proceeded far enough for Edison executives to outline terms (see document no. 27). In early August Variety reported: "It seems to be the general impression among the leaders of the motion picture business that a settlement of the fight now on is but a question of days, weeks or months."[9]

DOCUMENT No. 27 |

Proposed Scheme |

(1) Biograph Company to come in as Licensee under Edison patents the same as others. |

(2) Kleine to be recognized as Licensee, limiting importation to 5,000 feet of new subjects per week for entire list of foreign manufacture as advertised, including Gaumont. In case any foreign manufacture[r] drops |

(Text box continued on next page)

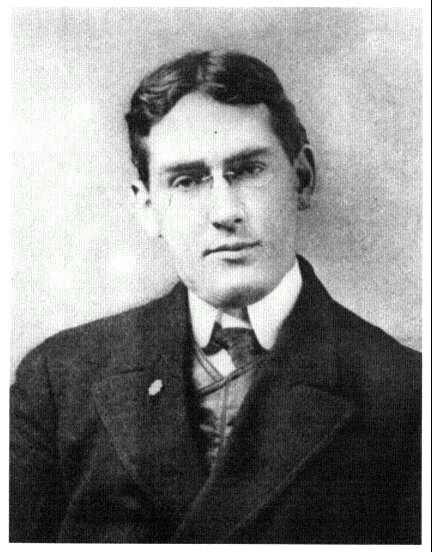

Frank L. Dyer.

out, the amount of film imported to be correspondingly reduced in proportion to his importance as shown by Kleine's output since February 1st, 1908. |

(3) Other Biograph licensees to be taken in (Williams, Brown & Earle, Italian Cines and Great Northern Film Company) on same basis as Kleine, the number of feet of new subjects to be based on amount of film put out |

(Text box continued on next page)

since February 1, 1908, but not to exceed a total of 2000 feet per week. |

(4) Royalties of present licensees and new ones above contemplated not to be increased. |

(5) All licensees to be licensed under Edison, Biograph & Armat patents, and royalties under Biograph and Armat patents to be collected preferably from exchanges who in turn will exact them from exhibitors. Royalties to be based on charge for rental service but not to exceed an average of $2.00 per week. |

(6) All projecting machines now in use to be licensed under all patents, and name-plate attached, limiting use of machines to licensed films. All projecting machine manufacturers to put on similar licensed plates. |

(7) All films to be leased for a limited period and restricted to use with licensed machines. |

(8) Cameraphone Company, Gaumont, or any other concern now making or contemplating making, talking pictures to be licensed, but limited to talking pictures and not to sell or lease films separately. Royalties to be ½ cent per foot and $5 per week or less for each machine. |

(9) Contract limited to two years, but to be extended from year to year until expiration of last patent. |

(10) Expenses for litigation to be borne by respective interests, each defending or prosecuting its own patents. |

(11) Expenses for litigation based on price-cutting or violation of license agreements to be borne pro rata by all licensees, up to $25,000. per year. |

(12) Price of film, net, to exchanges not to be reduced below nine (9) cents per foot, except by unanimous vote of all licensees. All votes to be on basis of running feet of new subjects. |

(13) All film to be bought from Eastman Company, who will collect film royalties. |

(14) Question of licenses to machine manufacturers and number of licensees, to be taken up and concluded after film situation is settled. |

SOURCE : Addendum to communication from Frank Dyer to H. N. Marvin, July 29, 1908, NNMoMA. The term talking pictures in point 8 refers to films shown synchronously with phonograph recordings. |

As the next step, licensed manufacturers met with Kleine, Edison, and Biograph interests. The substance of these negotiations was never reported, but the licensed manufacturers apparently insisted on substantial changes. The li-censors (Edison and Biograph) had planned to include almost every European producer in the new arrangement—but limit their future participation in the American market to current (mid-1908) levels. This would have coopted virtu-

ally all the opposition. The licensed manufacturers, however, wanted to restrict the scope of imported films and increase available supply by expanding their own production capacities.[10] They also wanted to increase their profits by raising the price for films. To further these goals, Biograph abruptly revoked the license of Italian "Cinès," and Edison licensees raised their prices from 9 to 11 cents per foot, effective September 1st.[11]

Agreement between the parties was close enough for the Motion Picture Patents Company to be incorporated in New Jersey on September 9th. Each company was searching for ways to maximize its position in the future combine. Pathé announced plans to open its own rental concern, following the examples of Vitagraph, Lubin, and Kleine, who had their own exchanges. This led to such strong protest among their regular customers that the offer had to be withdrawn.[12] Léon Gaumont visited New York in mid September and entered the negotiations.[13] An agreement was soon reached between Kleine and Gaumont that would allow Kleine to sell 2,000 feet of new Gaumont subjects each week.[14]

Negotiations encountered snags in October. "All talk of merger has dwindled to an extent that not even a whisper is audible in authentic circles," it was reported.[15] The licensed producers seemed to be the principal stumbling blocks. Articulating a viewpoint shared by his colleagues, one company representative "considered that group of manufacturers well able to cope with the demand [for films] for years to come, therefore he would not see the necessity or wisdom of taking in any other manufacturers."[16] Many of these manufacturers worried that additional reels of film supplied by the former independents would reduce their own sales.[17] Adding two weekly releases from Biograph and three through Kleine would increase the number of licensed subjects by approximately 40 percent. Licensed renters, in contrast, were extremely anxious to gain access to a more diverse product line, particularly since many of their customers wanted these films. The potential licensors were not unsympathetic to the renters' position and were ready to incorporate as much of the opposition within their ranks as possible, if only as a way to increase royalties. Offering itself as an impartial observer, Moving Picture World urged the two sides to reconcile their differences for the benefit of the industry.[18]

Griffith's filmmaking activities at Biograph had a somewhat contradictory impact on these negotiations. The high quality of his pictures generally strengthened Biograph's position. Theaters and renters wanted its films. Yet this success discouraged flexibility by Edison-licensed manufacturers. Even while denied access to FSA exchanges, Biograph increased sales per film from 30 + to 50 + prints between September and December 1908[19] Some Edison licensees had been selling as many as 100 prints per subject. If Biograph entered the licensed ranks, its sales would double again, and previously licensed manufacturers seemed likely to suffer.

Edison and Dyer were ready to strike a deal with Biograph's Harry Marvin

and Jeremiah Kennedy, except for the recalcitrant producers. According to Terry Ramsaye, Kennedy ended the long negotiations by threatening "to bust this business wide open" and give a Biograph camera to anyone who wanted it.[20] It was a clear signal to the manufacturers: reach an agreement or competition will be even more extensive. Negotiations began to move forward again. On November 18th the Film Service Association postponed a December membership meeting because "it will be necessary for the association members to meet the manufacturers early in January to consider new business arrangements."[21] While the final details were hammered out, the way for a new agreement was being cleared. On December 1st the manufacturers notified the renters that their relationship would fundamentally change in sixty days. Until then, licensed manufacturers could only terminate their relationship with an FSA exchange if it violated the contract. In the future they could simply terminate the contract with ten days' notice.[22] Whatever the terms of the new combination, renters had little choice but to accept them. When new snags materialized in early December, Edison made additional concessions to the licensed manufacturers. After more than five months of negotiations, agreement was finally reached.