Edison Features: 1907-1908

The continuity of Porter's representational system in the face of changes within the moving picture world can be seen in surviving Edison films and the criticisms of this work by contemporaries. A Race for Millions (August 1907) ends with a shoot-out between the hero and villain. This western interweaves studio-constructed exteriors with carefully selected locations. Many scenes use theatrical blocking with spatial and temporal condensations. Although a theatrical antecedent seems likely, it has yet to be located. The Trainer's Daughter; or, A Race for Love (November 1907), however, has a plot similar to Theodore Kremer's A Race for a Wife , in which the victor of a race between the hero and villain wins the bride.[142] Unless familiar with A Race for a Wife or aided by the exhibitor, spectators were likely to find the complex, unlikely story obscure. The film has no intertitles. Scenes were photographed primarily in long shot, sometimes making identification of characters difficult. This is particularly true in the case of the villain, who wears two different costumes during the course of the brief film. The significance of the second scene, in which the trainer's daughter offers herself as the ultimate stake, is not apparent unless one reads a plot summary (see document no. 24). The film's credibility and character motivation were undermined by the choice of a Miss DeVarney, who was plain and in her mid forties, to play the romantic lead. In contrast to later cinematic practice, Porter evidenced little interest in making the trainer's daughter an attractive woman who would be a suitable object of Jack's desire.

The first and last scenes from The Trainer's Daughter, which survive only as stills.

DOCUMENT NO. 24 |

The Trainer's Daughter |

SYNOPSIS OF SCENES. |

The trainer's cottage—The Lovers meet—The owner of the Delmar Stable and the Trainer come upon them unexpectedly—Jack is given to understand that his suit for the daughter's hand is not favored by the trainer. |

The exterior of the racing stables—Jack has one horse entered in the coming race for the Windsor Cup—Delmar also has a horse entered in the same race—Jack and Delmar lay a side wager on the winner—The money is placed in the Trainer's hands—The Trainer's daughter overhears the wager—They both seek her favor—She enters the wager by giving her heart and hand in marriage to the winner. |

Jack instructs his Jockey—The Jockey tries out Jack's horse—Delmar notes the time—Discovers his own horse has no chance against Jack's— Delmar bribes the stable boy to dope the horse—The Jockey overhears the plans. |

The racing stables at night—The Jockey arrives in time—Delmar and the stable boy prepare to dope the horse—The Jockey stops their plans— The fight—The blow—The Jockey down and out—They hide in a deserted house—The escape. |

The color room the following day—The hour for the race has arrived—The Jockeys leave for the mount—Jack's Jockey missing— Delmar triumphs—No one to ride the horse—The Jockey staggers in— The story—The villainy of Delmar exposed—The Trainer's daughter decides to ride in the Jockey's place. |

The call to the post—The Girl appears dressed in Jack's colors—The mount—The parade—The gong—They are off—The race—The trainer's |

(Text box continued on next page)

daughter is riding for something more than victory now—The home stretch—Neck and neck with Delmar's horse—Under the wire—The Trainer's Daughter wins. |

SOURCE : Moving Picture World , November 30, 1907, p. 639. |

Porter's next film, College Chums (November 1907) was loosely based on a well-known play, Brandon Thomas's farce-comedy Charley's Aunt . A Variety reviewer remarked:

Here's a comedy reel involving a comedy idea which has long been worked to death in burlesque, nothing less than what is called in the profession "seminary stuff." The subject is well enough handled and a variety of fairly humorous incidents is shown. By far the best feature was a mechanical trick scene. A young man and his sweet heart are shown in an altercation over the telephone. Both are seen in small circles at the upper corners of the field of vision, the rest of the sheet being occupied by housetops. As each speaks the words marshal themselves letter by letter in the air and travel across the intervening space. When the quarrel waxes hot the words meet in the middle of the scene and fall to the ground in a shower of letters. The story has to do with a young man who proposes and is accepted by the heroine. She sees him flirting with another girl and without confronting him at the time calls him up on the telephone, telling him the engagement is off. He declares that the other girl is his sister. She declares that she will call on the supposed sister at once. And so the young man's college chum is forced to disguise himself to represent the mythical sister. The sweetheart calls and the bogus girl and she grow entirely too chummy for the taste of her fiance. The girl's father further complicates matters by starting a flirtation with the counterfeit "sister"—a rather far fetched incident even for farcical purposes—and out of these intricacies the humor grows. The reel registered casual approval at the Fifth Avenue.[143]

The last two-thirds of the film is located in the young man's living room: this lengthy, single "shot" was actually photographed in several takes, with the actors exiting and reentering so that Porter could photograph the scene in sections. Actors behind the screen often brought this section of the film to life with quick repartee. This filmed-theater approach, for which the camera is a passive recorder, differs sharply from the animated trick scene that maximizes filmic manipulation and artifice. Here Porter supplied the words, using the technique of animated titles he introduced in 1905. As in the past, Porter juxtaposed various mimetic procedures for a syncretic, rather than internally consistent, mode of representation.

A Suburbanite's Ingenious Alarm (December 1907) was lauded as "another well constructed comedy. . . . The film has a good, up-to-date application and is very well-presented."[144] Its slapstick humor centers around a commuter's attempts to find a foolproof way to wake up in the morning. He "tries the old

Using animated titles in College Chums.

dodge of tying a rope to his foot to be awakened by."[145] Again Porter tells a simple story using a widely recognized situation. Overlapping time and action are employed as the scene moves between the interior and exterior of the commuter's home.

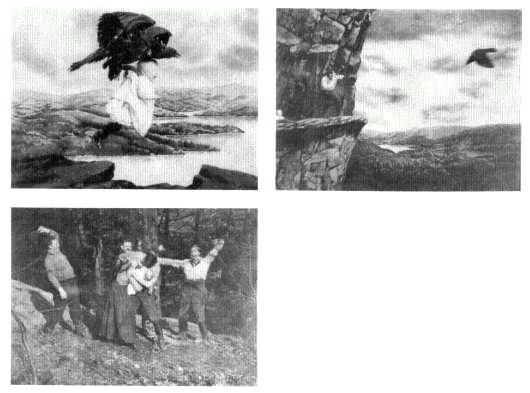

Porter's next film, Rescued from an Eagle's Nest (January 1908), is well known because it features D. W. Griffith in his first major film role. He plays a father who battles an eagle as he rescues his child from the bird's nest. The story for this family-centered drama was taken from a famous incident that the Eden Musee had enshrined in wax (see document no. 25). The film displays all the characteristic qualities of Porter's work. Rather than cut between parallel lines of action, Porter used temporal overlaps. Studio sets for exterior scenes were interwoven with outdoor locations. Despite the obvious abilities of a newly hired scenic artist, Richard Murphy, a precocious critic found the film "a feeble attempt to secure a trick film of a fine subject. The boldness of the conception is marred by bad lighting and poor blending of outside photography with the studio work, which is too flat; and the trick of the eagle and its wire wings is too evident to the audience, while the fight between the man and the eagle is poor and out of vision. The hill brow is not a precipice. We look for better things."[146] The reviewer demanded a consistently rendered visual world, with an emphasis on credibility that was not always valorized within Porter's rep-resentational system. Similar criticisms were to become more frequent in the months ahead.

Rescued from an Eagle's Nest concludes with a reunited nuclear family, their embrace cheered on by friends.

DOCUMENT No. 25 |

No. 8 THE EAGLE'S NEST |

This artistic group pictures a scene and incident which occurred in the Adirondack Mountains a few years ago. An eagle stole a little child and carried it to its nest high among the crags of the mountains. The father and neighbors pursued and battled with the eagle. After a long fight the eagle was killed and the child rescued. The greatest care has been taken in the coloring of the group, and the light and shadows are so perfect that at first view visitors think they are in the mountain tops witnessing a real battle. |

SOURCE : Eden Musee, Catalogue (New York, 1901), p. 4. |

Fireside Reminiscences (January 1908) is a family-centered "society comedy drama" that evokes the story line of the well-known song "After the Ball."[147] In this song, a man explains to his niece why he is single and has no children. One night when he and his sweetheart were at a ball, he found her in the arms of another man. He abandoned her without waiting for an explanation, and she

The husband reflects in Fireside Reminiscences.

eventually died as a result. After learning the man was her brother, he remained faithful to her forever. The ways in which Porter altered this story were consistent with earlier adaptations that add new family-centered elements. The lover is turned into a husband who sees his wife embracing her brother. Without waiting for an explanation, he banishes her from the home. Three years later the husband sits by the fire and recalls his past life in a series of dream balloon images: his wife, he and his wife embracing, their wedding, his wife and child, the moment he threw her out of the house, and his wife on the cold streets at night. This reminiscing is framed by a larger narrative. In fact, his wife is outside the house as he conjures up these images. She is brought inside, and their child acts as a catalyst for reconciliation. The family triumphs over the stern, misguided father, who finally sees the error of his ways and is quickly forgiven.

Surviving fragments of Cupid's Pranks , completed on February 10, 1908, but not released in time for Valentine's Day, make use of the charming, naive iconography of Valentine cards and similar illustrations. Filmed inside the studio except for matted shots of the New York skyline, Murphy's elaborate sets added an important element of spectacle. In this light comedy, Cupid brings two lovers together, arranges for their car to break down and turns back the hour hand of a clock to extend their meetings—all in the interest of love. After the couple fight and reconcile, they are finally married, with Cupid looking on approvingly. Many of these scenes are introduced by intertitles that make the story more

Cupid's Pranks.

Porter utilized widely available iconography like this for Cupid's Pranks.

concrete and guide the spectator. In some instances, they mask or "solve" problematic spatial/temporal transitions between shots.

Only a few fragments of Porter/Edison films made after Cupid's Pranks survive. Our understanding of Porter's work therefore depends on reviews in trade journals. Fortunately, these became increasingly common. Variety 's occasional film reviews commenced in 1907. The Dramatic Mirror , beginning with its issue of June 13, 1908, published systematic reviews of all films released during the previous week, a policy partially motivated by competitive pressures from Va-

Tale the Autumn Leaves Told.

Nero and the Burning of Rome.

riety . The Mirror reviews, written primarily by Frank Woods, offered carefully reasoned judgments that strongly supported the emerging, more modern representational practices. By late September, Moving Picture World responded with its own section of film reviews. Many of these were written by W. Stephen Bush, who remained sympathetic to Porter's approach.

Porter's work generally received strongly favorable comment during the first six months of 1908. Animated Snowballs was "a good interesting comedy run" that was well liked by the audience seeing it with Sime Silverman of Variety . Sime offered a few muted criticisms: the narrative was temporarily forgotten to show an accomplished figure skater, and the realism of the chase was ruined by the premise of a gouty old man successfully pursuing two young boys on figure skates. Nonetheless: "Some novel effects are shown. Snowballs roll uphill, and men also turn somersaults up the same incline. The opinion that the film is being reversed in the running is dissipated by some attending circumstances. It is not possible for a layman to figure out how it has been accomplished."[148]

After viewing The Cowboy and the Schoolmarm (March 1908) at Keith's, one correspondent called it "a specially good film" and reported, "We never saw an audience so affected by a picture show as when the cowboy on the gallop picks up and rescues the kidnapped school teacher."[149] Another referred to Tale the Autumn Leaves Told (March 1908) as "Edison's masterpiece."[150] For each scene, the frame had a different mask cut in the shape of a leaf. Thus the title was cleverly and visually transposed. Nero and the Burning of Rome (April 1908) likewise received much favorable attention. One unhappy critic excluded only this Porter film from a more general lament. "This subject is spectacular, contains many elements of human interest and possesses the dignity of history," he explained.[151]Bridal Couple Dodging Cameras (April 1908) was called "a really novel comedy subject" and "one of the best comedy reels the Edison people have ever turned out."[152]Skinny's Finish (May 1908) was "in the best Edison style and should prove popular for some time to come."[153]

Porter's The Blue and the Gray; or, the Days of '61 (June 1908) garnered the highest praise. "No film that has been issued by any company in a long time can be classed with The Blue and the Gray for consistent dramatic force, moving heart interest and clearly told story," declared the Dramatic Mirror .[154]Moving Picture World felt it was "one of the few film subjects that deserves a long run and which the public will pay to see more than once."[155]Variety agreed, calling it "a commendable moving picture."[156] This story of North and South had many familiar narrative incidents that were often utilized by the popular press and theater. Two West Point classmates end up on opposite sides of the war. The Union officer hides his old friend and his sister's true love from his commander. When both are discovered, the Union officer is sentenced to be shot. The sister wins a pardon from the great reconciler, Abraham Lincoln, and arrives with the reprieve as her brother is about to be executed.

Despite the familiar incidents, Moving Picture World felt this "masterly production of thrilling interest . . . could be made clearer by more explanatory titles."[157]Variety found the impersonations of Grant and Lincoln somewhat less than credible and the sister's pleading with Lincoln for a pardon too brief to convey the complexity of the situation and therefore unrealistic. The Dramatic Mirror questioned its temporal construction:

In only one point does the construction of this story appear faulty and that is when the young officer has been stood up to be shot and the command of "fire" is about to be given, the scene is shifted to Washington where the girl is pleading with President Lincoln. The spectator is thus asked to imagine the firing squad suspending the fatal discharge while the girl rides from Washington to the Union Camp. It would have been better if the Washington scene had been inserted somewhat earlier.[158]

Although this successive presentation of two separate lines of action was typical of Porter's earlier chase and rescue films, the reviewer already assumed that linear temporality provided the proper basis for cinematic construction and perceived Porter's customary methods of narrative construction as awkward.

Love Will Find a Way (June 1908) was commended as an "excellent comedy film, since it is based on a central idea which is humorous in itself."[159] With Pioneers Crossing the Plains in '49 (June 1908), "Edison has given us a very good film in this story of pioneer days. The scenery is excellent and the picture artistic." Nonetheless, the reviewer felt "the film could have been improved in the battle with the indians by the 'pioneers' displaying more judgement in defending themselves instead of standing aimlessly in the open to be shot down like sheep."[160]Honesty Is the Best Policy (May-June 1908) had an excellent story and theme, but its effectiveness was spoiled by "faulty construction and the introduction of incidents that have nothing to do with the development of plot."[161] Ironically, the innovations that many historians have attributed to Porter based on the modernized version of Life of an American Fireman — parallel editing and matching action—were the very procedures that Porter had the greatest difficulty executing. Porter's work was becoming more and more out of step with the emerging mode of representation.