The Biograph Association of Licensees

The Association of Edison Licensees and the Film Service Association had limited ability to implement their desired regulations because important enterprises stayed outside the combination. The American Mutoscope & Biograph Company and George Kleine were not given the opportunity to join the Edison combination in a capacity commensurate with their economic or legal positions. They formed an opposing organization based on Biograph's productions and patents and Kleine's European imports and chain of exchanges. Italian "Cinès"; Williams, Brown & Earle; and the Great Northern Film Company were also given Biograph licenses to import films from abroad.[32] Altogether they offered a "regular weekly supply of from 12 to 20 reels of splendid new subjects."[33] Furthermore, Biograph announced its intention to license local domestic producers. Although it did not follow up on these threats, companies like Goodfellow Manufacturing operated in cooperation with the Biograph group.[34] The resulting "film war" was waged simultaneously on the legal front through the courts, on a commercial front through pricing and marketing strategies, and on the production front through the efficient manufacture of popular films.

On the legal front, Edison sued Biograph and the Kleine Optical Company in March for infringing on a film patent, reissue no. 12,192, that had not previously been tested in the courts.[35] To strengthen its position, Biograph acquired the "Latham loop" patent from the E. & H. T. Anthony Company for $2,500 and used it to bring countersuit against the Edison Company and its various licensees.[36] Lengthy discussions in the trade were devoted to the value of the Latham loop, which Frank Dyer regarded "as so unimportant as not to warrant serious consideration."[37] George Kleine and Biograph's Harry Marvin, in contrast, insisted the loop was essential for making films over 75 feet in length.[38] Biograph also formed an alliance with the Armat Motion Picture Company on March 21st, thereby gaining access to its patents covering motion picture projection.

"We were engaged in bitter commercial strife," Harry Marvin later explained. "We did what all people do under those circumstances. We fought the best we knew how. We belittled the possessions of our enemies, and we magnified our own possessions."[39] Between March 16th and April 30th, the Edison Company brought suit against thirty theater owners in the Chicago area and six in the Eastern District of Missouri (St. Louis) and the Eastern District of Wis-

consin (Milwaukee) for showing films produced or imported by the Biograph licensees.[40] William T. Rock, a longtime believer in patent litigation as an effective commercial weapon, was delighted. "Why, man, all they have to do is to draw up a general complaint, print fifty or a hundred copies and file suits in as many cities of the Union," he told a reporter. "This can be done at very little expense, but look at the thousands of dollars that will have to be spent by the other side in engaging lawyers and defense for all these suits."[41] Kleine, identifying the Biograph licensees as "independents," observed that these suits were attempts to drive users of independent films into the Edison circle by questionable methods. He appealed to "the characteristic feeling of stubbornness in the average American which prompts him to resent such an attempt to compel him to violate his principles of independence."[42] Accepting the argument that such actions constituted harassment, the courts prevented Edison from bringing additional suits against Kleine's customers until the principal suits were resolved. To maintain the balance of anxiety, Biograph and Armat initiated legal action against William Fox's Harlem Amusement Company and a chain of twenty Chicago theaters in late May.[43] Many companies that had joined the Edison association thinking it would bring legal peace were disappointed when the warfare intensified and the uncertainty remained.

On the commercial front, the Edison licensees and Film Service Association cut prices 20 percent to maintain their competitive position. Unaffiliated exchanges were also allowed to join the FSA at the old $200 rate[44] even as the renters' return of old films to the producers was quietly deferred.[45] While able to consolidate their initial advantage, the Edison affiliates could not eliminate the opposition. In an interview, I. W. Ullman of Italian "Cinès" admitted that his company had experienced "the forced shrinkage in our market, beginning March 2, 1908, of upwards of 75 per cent."[46] Reports reaching Frank Dyer at the Edison office, however, document the resurgence of the independents in some areas of the country. Writing in late April, Laemmle reported that "there is no denying the fact that the Independents are getting stronger day by day." He enclosed a letter from his manager in Evansville, Indiana, predicting that "this whole section is going to the independents within the next ten days if something is not done and done mighty quick."[47] The independents moved rapidly to establish their own nationwide network of film exchanges. George Kleine, who sold his Kalem Company shares to avoid conflicting interests, opened new branches until he had offices in twelve key cities.[48] Williams, Brown & Earle inaugurated a Philadelphia exchange much against their will; nonetheless, it soon proved profitable.[49] A small group of established exchanges also went over to the independents.[50]

The exclusion of many European and select American producers from the Edison ranks resulted in a serious dearth of subjects. A New York critic visited ten nickelodeons in his neighborhood and found that nine were showing the

same first-run films.[51] This was particularly notable along Manhattan's Fourteenth Street, where the Unique, Dewey, Pastor's, and Union Square theaters were "determined to have none but the newest and latest films obtainable from the Edison side."[52] The same pictures were shown in all four theaters. In July the Unique jumped over to the independents to secure fresh subjects. Other large theaters in New York and Brooklyn made a similar switch at about the same time.[53] The Dramatic Mirror reported:

Changes of service have been made both ways by theatres in different parts of the country, and such changes are bound to occur from time to time so long as the field is divided into two camps. Neither side is turning out enough new subjects to supply the entire market, and managers who do not want to give the same pictures as their neighbors, or who think they can get better service by changing, will change. In the long run the best output of subjects will prove the most profitable—that is, providing patent litigation does not wipe out one side or the other.[54]

Since the independents helped to satisfy the nickelodeons' desire for product diversity, the Edison group found it difficult to push them from the field using strictly commercial methods.

The extent to which independent films were available in the New York area was suggested by Edison's industrial spy, Joseph McCoy, who saw 515 films while visiting 106 different storefront theaters in June. Of these films, 57 had been made by the independents and the rest by Edison licensees; however, McCoy saw 133 of them at the Elite Theater in Newark, New Jersey, which showed only licensed films. Disregarding this theater, the independents provided about 15 percent of the films that McCoy saw. Of these 57 films, 15 were made by Biograph, 13 by Italian "Cinès," 11 by Gaumont, 10 by Urban-Eclipse, and 8 by Nordisk. In contrast, the Edison Company alone supplied 45 of the films viewed by McCoy.[55] Despite their small share of the film business, the independent or non-Edison combination made it difficult for the Film Service Association to maintain discipline within its ranks. Expulsions for violations would not put the guilty exchanges out of business but send them into the opposition camp, further strengthening the Biograph licensees and weakening the Edison position.

The Edison group was internally disorganized, with considerable animosity existing between rival FSA exchanges. Despite its recently exposed duping activities, the 20th Century Optiscope Company proclaimed its own determination "to live up to the rules and regulations in every way." It accused the Yale Amusement Company—its principal competitor in Kansas City—of price cutting and asked the manufacturers to make an example of it by stopping its supply of films.[56] A. D. Plintom of the Yale Amusement Company insisted on his own integrity and called the "Twentieth Century people . . . very unscrupulous in their methods."[57] William Swanson, who was on the FSA executive

board, complained that "here in Chicago the kikes have organized among themselves" to the detriment of the business. He characterized three or four renters— whom he was responsible for organizing into a local association—as vultures, blood suckers, thieves, and price cutters.[58] Swanson was clearly jealous of Laemmle's success. The Standard Film Exchange informed Dyer that Swanson's animosity toward them had existed before the formation of the association and invited "close scrutiny of our business methods at any and all times."[59] The Yale Amusement Company accused Swanson of illegally opening a branch office in Kansas City and severe price cutting as he attempted to win a toehold in his new territory.[60] Other exchanges also opened unauthorized branch offices.

By June 1908 the situation had become serious enough for Thomas Edison to intervene publicly. Claiming that he was "for the first time taking a personal interest in the strictly commercial side of the business," he put the full weight of his authority behind the venture. In an interview with Variety , he announced,

I am aware of some of the restlessness and minor dissatisfactions among the dealers. This is a natural condition. No big movement was ever perfected without experiment. That's what we are doing now—experimenting. And I may say we are experimenting to some purpose.

What we want to see is a system of business in which everybody is satisfied, everybody making money and getting a full return upon his investment of brains, money and labor. This is the goal toward which we are working. If the progress at times seems slow, it is none the less sure, and our arrival there is a matter of a very short time. This is a great organization. It cannot be administered haphazard[ly]. Each movement must be carefully considered.[61]

The Association of Edison Licensees was likened to an invention that would be improved through constant tinkering and experimentation. Now that the Wizard himself had intervened, the problems would be solved to everyone's satisfaction.

Edison was already enjoying financial benefits from the new organization. Beyond the Edison Company's impressive film-related profits of $410,959 for the 1908 business year, the inventor was receiving additional monies from his licensing arrangements. Lubin sent Edison $3,200 in royalties for the period between February 1st and June 20th.[62] Essanay paid approximately $6,000 during the first year, Pathé $17,000 or $18,000.[63] Edison's total royalty for the first year approximated $60,000.[64] Yet Edison and association members realized that the imperfect nature of the "trust" prevented the organization from operating effectively. Many considered an alliance of Biograph and Edison interests as the only way to achieve the associations' original goals.

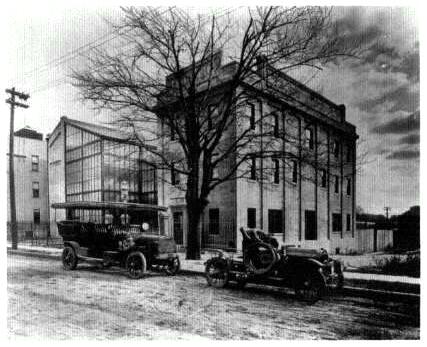

The new Bronx studio.