A Transformation in the Realm of Exhibition

The rapid proliferation of specialized storefront moving picture theaters— commonly known as nickelodeons (a reference to the customary admission charge of five cents)—created a revolution in screen entertainment. In retrospect the ten-year period between 1895 and 1905 witnessed the establishment and finally the saturation of cinema within preexisting venues. Reviewing vaudeville in late 1905, the new publication Variety declared that "in the present day when a special train is hired and a branch railroad tied up for a set of train robbery or wrecking pictures, the offerings are really excellent and those who remain

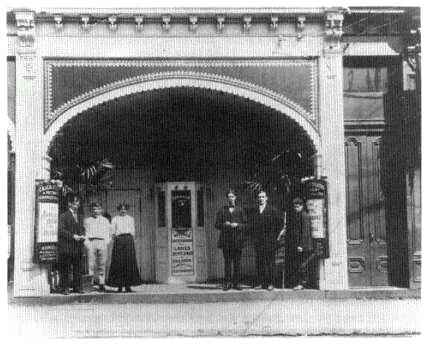

Early nickelodeon theaters such as this one transformed the film world.

and watch them, get sometimes what is really the best thing on the bill. The picture machine is here to stay as long as a change of film may be had every week."[1] Regular Sunday motion picture shows were being given in many eastern cities, and traveling motion picture exhibitors prospered and increased in numbers. Penny arcades and summer parks boasted of numerous picture shows by 1904-5. Such success pointed to the potential viability of specialized picture houses.

Nickelodeons transformed and superseded these earlier methods of film exhibition. They were more than simply specialized motion picture theaters—a common, if often ignored, venue for film exhibition since 1895. The new exhibition mode was made possible by a large and growing, predominantly working-class, audience; the existence of rental exchanges, which facilitated a rapid turnover of films; the conception of the film program as an interchangeable commodity (the reel[s] of film); a "continuous" exhibition format; a sufficient level of feature production to meet demand for frequent program changes; and the relative independence of film exhibition from more traditional forms of entertainment. The nickelodeon phenomenon developed first in the urban, industrial cities of the Midwest, beginning in Pittsburgh, where Harry

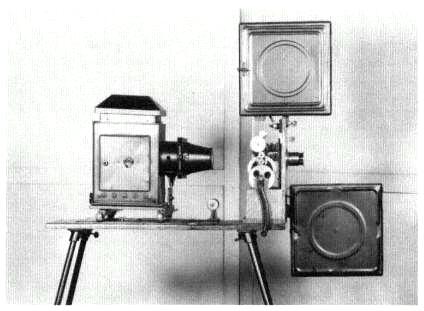

An Edison Exhibition Projecting Kinetoscope, ca. 1907-8.

Davis opened his first Pittsburgh storefront theater in June.[2] With the area's working classes enjoying unprecedentedly high wages, Davis's experiment was a success and was quickly imitated in Pittsburgh, Chicago, Philadelphia, and elsewhere. The "nickel madness" of motion pictures spread outward from its midwestern, urban base in an uneven pattern, taking almost two years to reach all parts of the United States.

Although nickel theaters were being recognized as important exhibition outlets by early 1906, New York City, the nation's production capital, did not feel their presence until that spring.[3] Within six months New York was assumed to have "more moving picture shows than any city in the country."[4] In Manhattan the largest concentration was on Park Row and the Bowery, where at least two dozen picture shows and as many arcades were scattered down a mile-long strip. Their principal patrons were Jewish and Italian working-class immigrants.[5] While these groups made up the hard-core moviegoers, middle-class shoppers from the Upper East and Upper West sides helped to support the theaters along Fourteenth Street and Sixth Avenue. When members of the elite or leisure class saw films, they did so at travel lectures like those given by Burton Holmes or at vaudeville performances, not in dingy storefronts.

As newspaper editorials soon made clear, the "better classes" viewed the nickelodeons with contempt and alarm.[6] The sense of farce and anarchistic play

in the comedies and the condemnation of the rich, not only in social message films like The Kleptomaniac but in more conventional melodramas, could be reinterpreted in ways that might threaten the status quo. Both the appeal to sexual desire and pleasure and the depiction of violent and transgressive acts (robbery, murder) encountered strong condemnation from conservative religious groups. Moreover, nickelodeons facilitated ideological slippages or disjunctions in the reception of films: audiences tended to appropriate pictures for their own purposes, which were often quite different than those intended by the filmmakers and production companies.

Nickelodeons created "the moviegoer"—a new kind of spectator who did not view the pictures in vaudeville formats, as one of many offerings at the local opera house, or as part of an outing to the summer park. To attract these often devoted patrons, storefront theaters found it profitable to change their offerings with increasing frequency. New programs were being offered twice a week in July 1905, and three changes each week were becoming common by late 1906.[7] During the following year, many nickelodeons began to change programs every day but Sunday.[8] The lateral expansion of motion picture houses across the country and this vertical increasing frequency of changing programs caused a tremendous demand for films.

Immense opportunities were created not only for exhibitors and producers but for film renters, who operated at the interface between production companies and exhibitors. In the historical model offered here, distribution is not seen as a fundamental aspect of cinema's production, like film production, exhibition, and viewing. The point at which film production and exhibition meet, however, becomes of central importance in a capitalist system. It can be likened to a fault line where two tectonic plates confront each other, creating large quantities of energy. Screen history suggests a "law": significant changes in either the mode of exhibition or the mode of film production will create new commercial opportunities at this interface. The nickelodeon boom was a revolution in exhibition on an unprecedented scale. Those who took advantage of this golden, fleeting opportunity were to later control the industry—William Fox, Marcus Loew, Carl Laemmle, and the Warner brothers. The rise of a new generation of film exchanges proved to be a crucial moment in the industry's history.

Chicago became the first and largest center for new film exchanges. Eugene Cline, Max Lewis's Chicago Film Exchange, and Robert Bachman's 20th Century Optiscope had become active film renters by 1905.[9] They were joined by William Swanson in the spring of 1906.[10] William Selig, who did not enter the rental business himself, aided Swanson financially. Carl Laemmle became unhappy with the high-handed treatment he received when renting films for his two Chicago theaters in mid 1906.[11] Rather than open more nickelodeons, Laemmle started his own exchange in October and attracted customers by of-

fering "service" as well as a reel of film.[12] The film rental business in New York was at least six months behind Chicago. The new generation of exchanges did not appear until early 1907. Nickelodeon manager William Fox, for example, only opened his Greater New York Film Rental Company in March 190.[13] Increasingly renters appeared in cities outside the traditional centers of New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia.

Thriving exchanges were hampered by a shortage of new pictures. When Laemmle listed popular subjects for rent in May 1907, he included some that were almost two years old—for example, Edison's The "White Caps " and The Watermelon Patch .[14] The demand for films encouraged several groups of film veterans to move into production. Vitagraph recognized the shifting realities of exhibition and greatly increased its fiction film production. It began to sell prints of these original subjects to other renters in September 1905.[15] In early January 1907 George Kleine joined with Samuel Long and Frank Marion, both of Biograph, to form the Kalem Company, which was incorporated in May and began to sell films in June.[16] At about the same time, George Spoor, who owned the Kinodrome Film Service and National Film Renting Bureau, joined with Gilbert M. Anderson, who was then directing for William Selig, and formed Essanay.[17] The large demand for film not only created incentives to start new production companies, it benefited established manufacturers such as Edison.