3. The Armature of Khalqi Power

Having considered Taraki’s life history and his relation to the party, I now consider how the Khalqi government attempted to reinvent the relationship between ruler and ruled. I have already noted various ways in which Taraki and the PDPA leadership deviated from established notions of who rulers could be and whom they should rely on. In this chapter, I consider the manner in which the government presented itself to the people it ruled, how it sought to enlist their support, and how those attempts to mobilize the population diverged in significant ways from long-established understandings of how the government should operate in its dealings with the people. Style is substance, no less in Afghan politics than in our own, and successful politicians learn to negotiate the protocols and practices of their society. The Khalqis, however, in their mode of self-presentation misjudged the needs and wishes of the Afghan people at every stage. Before examining the Khalqi case, I discuss the manner in which some preceding rulers related to their subjects in order to contextualize the strategy chosen by the revolutionary regime.

The first point to note in this analysis is an obvious one: the PDPA government saw its role differently from the way earlier Afghan rulers saw theirs. To take Abdur Rahman again as a point of departure, in his view the sovereign’s primary responsibilities were ensuring the security of the kingdom and providing an orderly and peaceful atmosphere in which his subjects could be free to fulfill their divinely appointed duties as God-fearing Muslims. There was nothing in this social contract about ensuring happiness or prosperity or equality of opportunity, and indeed it was not a social contract at all that bound ruler and ruled but rather divine injunction: “Everyone’s share is determined by God on the basis of his merit, circumstances, and capabilities. Your king also pays attention to these ranks among the people. He has appointed each one of you in one of these ranks from the commander-in-chief to the common soldier. Each one stands in his own place and position, and hence you people should be grateful to God and to the king.” [1]

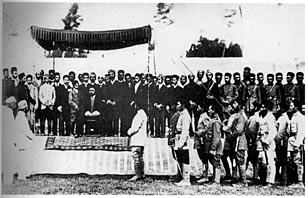

A graphic representation of the traditional relationship of ruler and ruled is seen in a photograph (Fig. 3), probably taken in 1903, that shows Amir Habibullah, son and successor of Abdur Rahman, at an official darbar (court reception) in Kabul. Standing next to the amir is his son, Amanullah, and arrayed to each side are various court officials and advisors to the amir. A row of soldiers and lesser officials fill the rear of the photograph, while notables in line in the foreground wait to pay their respects to the king. Everyone in the picture is dressed in Western-influenced clothing, but the elements of style are still traditional—the amir alone is seated, the raised platform and carpet indicate the exalted position of the king and his court, the canopy overhead protects the royal party from sun or rain, and the presence on the amir’s right of his young son signals the continuity of the royal line. Also instructive is the fact that the ruler looks neither at the camera nor at any individual in the picture. The assembly is turned toward the ruler, but the ruler heeds his own counsel.

3. Amir Habibullah dabar c. 1903 (Khalilullah Enayat Seraj Collection).

Habibullah was a modernist in one sense—he liked Western inventions, be they automobiles, photography, or golf; but he had little time for the political and social agendas that modernists brought with them and that began to sweep through his kingdom in the first two decades of the century. His son and successor, Amanullah, however, took a different tack. Heavily influenced by his intellectual mentor and father-in-law, Mahmud Beg Tarzi, Amanullah wanted to transform Afghanistan into a modern nation, and he set about that task shortly after he took power in 1919. As noted in the previous chapter, Amanullah was much given to trying on new ideas, as well as different styles of clothing. The most significant of these ideas was that government had a role to play in improving people’s lives. This idea was not original to him; Ottoman and Indian intellectuals, among others, had been formulating the outline for a new Asian and Islamic renaissance in which the non-Western peoples would combine Western advances in science, technology, and political democracy with Asian spiritual and social values. Amanullah intended to be at the forefront of this renaissance, and he demonstrated this commitment through the promulgation of economic and social reform programs meant to improve the social conditions of ordinary people and through the adoption of a more informal and democratic manner of dealing with his subjects.

Though most of Amanullah’s economic reforms were directed toward rationalizing the government’s financial infrastructure and developing new industries, he outstripped the Khalqis in the area of social reform, especially with regard to women’s rights and education. In keeping with his commitment to change, Amanullah adopted a relatively nonhierarchical manner of interacting with subordinates, as indicated in the following assessment by the British diplomat Sir Henry Dobbs, who met Amanullah in 1921 during treaty negotiations:

His Majesty Amir Amanullah Khan is himself probably the most interesting and complex character in his dominions. His manners are popular, jocular and easy to such a degree that even in his public appearances he sometimes lays himself open to a charge of want of proper dignity. In private he loves to indulge in sheer horseplay, changing hats with his courtiers, throwing bits of bread at them or sprinkling them with soda-water, and making most intimate and daring jokes about their wives, families and personal appearance. He eschews all ceremony except in the most formal durbars, dislikes elaborate uniforms and affects a spartan simplicity in his clothes, usually not even wearing a shirt beneath his rough military jacket. Collars, ties and cuffs, which were de rigueur in his father’s time, are now forbidden at his Court. . . . When transacting business he is extremely polite and gentle in manner to his Ministers and courtiers and bears himself among them merely as primus inter pares, encouraging them to argue with him freely and appearing to trust to his superior agility of mind for the gaining of his ends. [2]

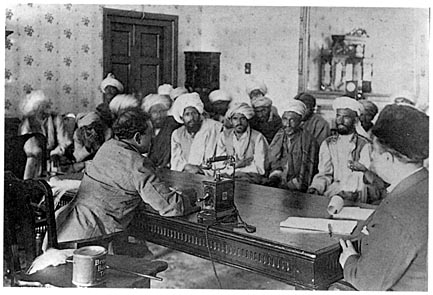

One can get a sense of Amanullah’s manner of relating to his subjects in a photograph (Fig. 4), taken in about 1925 in the winter palace at Jalalabad, that shows the amir meeting with tribal leaders. In the photograph, Amanullah is seated on the same level as his tribal subjects and appears to be looking them squarely in the eye. He has eschewed ceremonial garb in favor of a rough military jacket of the sort Dobbs noted, and he seems intent on pressing closer to the leaders, even as they appear intent on maintaining a wary distance. In this meeting, we see no sign of the usual entourage of retainers and officials of the sort that Habibullah usually surrounded himself with; a single secretary with pen and paper is seated to his right, and a spare number of trappings of office are nearby: a fly whisk behind him, a clock across the way, and a telephone set close at hand.

4. Amir Amalullah meeting with tribal leaders, Jalalabad, 1925(?) (Khalilullah Enayat Seraj Collection).

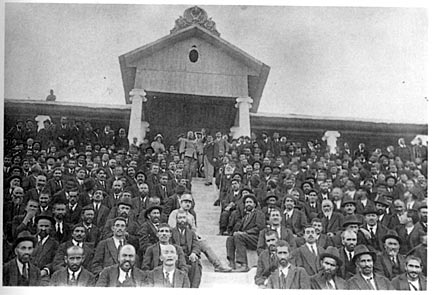

Coming from a more populist tradition, Americans tend to admire this sort of behavior, but Afghans had a good deal more trouble with it, especially with Amanullah’s egalitarian treatment of women. For Amanullah, women’s rights may have begun as a political issue, but they became personal for him after his marriage to the daughter of his mentor, Mahmud Beg Tarzi. Soraya was well educated herself, and Amanullah appears to have been devoted to her, as evidenced by his unwillingness to follow the usual royal practice of contracting numerous marriages for alliance, convenience, and pleasure. Amanullah’s commitment to monogamy was strange enough, but his concerted efforts to reform other customary restrictions on women and girls, as well as his willingness to have Soraya appear in public without a veil, outraged many of his subjects. So too did other mostly symbolic but no less unorthodox gestures, such as his requirement that all delegates to the national assembly (loya jirga) in 1928 wear Western suits. [3] Figure 5 commemorates this occasion, which followed on the heels of Amanullah’s grand tour of Europe, during which he had developed new ideas for the social and economic development of his country. The setting of the photograph was the bleachers of the Paghman race track. Amanullah had spent five days telling the delegates about his trip and his plans for the future. At the moment the photograph was shot, the amir is standing at the top of the aisle, saluting the photographer. Over to the side, his wife, Soraya, wearing the thinnest of veils, stands out as the only women in a sea of male faces—all of whom are dressed in the requisite suit and tie.

5. Meeting of parliamentary deputies, Paghman, 1928 (Khalilullah Enayat Seraj Collection).

Following Amanullah’s abdication and the short-lived reign of Bacha-i Saqao, and with the brief exception of the chaotic period of democratic liberalization in the late 1960s, rulers returned to the more autocratic style that Afghans knew and understood. The first of these rulers was Nadir Khan, a former general who governed in a martial fashion. He was assassinated in 1933, apparently as part of a long-standing family feud, and was nominally succeeded by his teenage son, Zahir Shah, though for the next thirty years power resided principally with his uncles (Muhammad Hashim and Shah Mahmud) and cousin (Muhammad Daud), who ruled sequentially as prime ministers until 1963. [4] During this period, social reforms were gradually introduced, but in a nonconfrontational, nonthreatening way; for example, in 1959 the wives of the prime minister and other important government officials appeared unveiled on the viewing stand at the independence-day ceremonies. Afghans saw that this sort of behavior was once again condoned by the government, but no one was forced to go along, and, in fact, most people outside the upper and middle classes in Kabul chose to ignore the example. The archetype of the mid-twentieth century ruler was, in many respects, Muhammad Daud, who served as prime minister from 1953 to 1963 and as president of his short-lived republic from 1973, when he overthrew his cousin Zahir Shah, until the Saur Revolution in 1978.

Seen in a photograph taken at Persepolis during an official trip to Iran (Fig. 6), Daud was a forbidding but also perplexing figure. During his tenure as president, portraits of the baldheaded Daud glowering at passersby through half-tinted glasses were omnipresent in teahouses and offices. But it was never quite clear what Daud stood for. Was he a leftist—the so-called red prince of his early years—or a Pakhtun nationalist? During Daud’s term as prime minister confrontations with Pakistan regarding the status of the border tribes reached their peak, but he also actively sought Soviet patronage. No one knew where Daud stood for sure, and one might read his vaguely menacing stare as masking a deep uncertainty as to what he wanted to accomplish with his power. Certainly, people didn’t know what to make of him, and while some feared his anger, they also finally didn’t find him that significant in their lives.

6. President Muhammad Daud, Persepolis, n.d. (courtesy of Qasim Baz Mangal).

Ruler and Ruled

The people recognize me by the name of Taraki which is the well-known name of my tribe and clan. But I say openly that I do not belong to any particular tribe or clan. I belong to . . . the Pushtuns, Hazarah, Uzbek, Tajik and all the country’s nationalities, noble tribes and clans, and I live in the hope of serving the hard-working peoples of this country. [5]

Taraki made the preceding statement in a meeting with elders from various provinces a little more than a month after coming to power, and one can only wonder how it was taken by those assembled to meet the new leader. They, after all, had been called to Kabul precisely because they were representatives of particular tribes and clans, and their status as Pakhtuns, Hazaras, Uzbeks, and Tajiks was evident to anyone who saw them in their ceremonial clothing or heard them speak in their native languages and dialects. In the midst of these representative types, Taraki claimed to be no type at all. Perhaps he hoped to appropriate the interstitial status that the Durrani dynasties had developed for themselves over two centuries of rule. People, after all, had not generally thought of the royal family as being associated with a particular tribe, despite their Pushtun roots. Most of the royal family members spoke Dari Persian among themselves, and some spoke Pushtu only haltingly. [6] More important, many Afghans viewed the royal family as having its own interests but not as favoring any particular ethnic group or tribe among those constituting the Afghan people, loyalty to the royal family itself being more significant than ethnicity. Taraki was not from the royal Muhammadzai lineage, however, and his assertion that he belonged to no group must certainly have rung false to those who heard it, as it would have if anyone among them had stood up and made a similar declaration. Religious leaders—particularly Sufi mystics—could profess their nonattachment to worldly allegiances, but a secular politician could not, and one must assume that those who listened to Taraki’s address and many more like it did not gain a great deal of confidence from what he had to say.

That Taraki should try to engage his audience in this way is not surprising. The truth was that his regime desperately needed popular support. Despite initial claims in the government press that the PDPA had fifty thousand “members and close sympathizers” or the assertion made in July that the government was run by “millions of honest, courageous and patriotic people of Afghanistan . . . from every tribe and region in the country,” [7]the new regime probably had only a few thousand committed members at the time of the revolution, and its ethnic base of support narrowed considerably after the Parchami purges of mid-July took out most of the non-Pakhtun leadership. In certain respects, the situation faced by the PDPA was similar to that of Amanullah when he took power after the assassination of his father in 1919. On that occasion, many people suspected that Amanullah himself might have had a hand in the assassination, a suspicion that appeared to be substantiated when he imprisoned his uncle and older brother, both of whom had a better claim to the throne than he did. Amanullah succeeded in stifling any move against him, however, by redirecting popular discontent into a short-lived border jihad against the British in India. Since religious leaders (who had been his uncle’s primary supporters) had been calling for a jihad for years, Amanullah defused any immediate attack against him and thereby bought the time he needed to consolidate his authority. [8]

The PDPA did not have a recognized foreign bogeyman to turn to, and the action that it had to defend was not a dynastic upheaval, which Afghans understood, but a revolution, an inqilab, which was an entirely unprecedented occurrence. Choosing the cautious path, the regime initially attempted to conciliate rather than upset the people it hoped to lead, soothing suspicions by inviting rural elites to meet the new ruler in darbar in Kabul. This was the traditional custom: bring the elders to the palace, present them with ceremonial robes and turbans, and assure them that the new rulers would treat them well and respect their autonomy. Taraki was new to the role, but he did his best; all through May and June, government newspapers published photographs and stories of the new leader meeting with groups of religious leaders and provincial elders. The vast majority of elders came from the Pakhtun frontier areas, including areas under Pakistani control, and it was not difficult to ascertain why the government sought out leaders from these areas. [9] This is where most acts of antistate violence over the preceding hundred years or so had originated, and, even more than Bacha-i Saqao, it was the border tribes that had been responsible for sealing Amanullah’s unhappy fate. The Durranis of Qandahar may have been the erstwhile tribe of kings, but the Pakhtuns of the frontier were the kingmakers and breakers, a fact that Taraki alluded to when he told a group of Pakhtun elders, “You brother tribes be aware and consider the bitter experience of the Amani movement [those who supported the reforms of Amir Amanullah]. . . . The state is yours. It is not your master. It is your servant.” [10]

The parade of elders continued through May and early June but then abruptly stopped in July, about the same time as the Parchami purges. [11] At this point Amin’s ascendance began in earnest, and the first sign of his new power was the adoption of a more aggressive plan of reform. From this time forward, the policy of conciliating traditional elites appears to have been abandoned in favor of a more radical and reckless plan to mobilize the rural poor, who had never before been treated as politically significant by the government in Kabul. Under Amin’s leadership, the regime staked its future on an alliance with small landholders, tenant farmers, agricultural laborers, and women—politically dormant segments of the population that no previous regime had ever taken seriously. While they represented the largest percentage of the people of Afghanistan, the rural poor had been too preoccupied with making ends meet and too oppressed by rural landowners and creditors to have ever taken much interest in politics or to have speculated on the potential of government for making their lives better. Henceforth, however, the nontribal peasantry was to become the bulwark of the regime, while the tribal elders and other rural elites, whom the regime had initially tried so hard to impress, were labeled “feudals” and “exploiters,” the enemies of the people and the state.

The first stage in Amin’s campaign to politicize and mobilize this population came in mid-July with the promulgation of Decree #6, whose objective was to ensure “the wellbeing and tranquility of the peasants [by] relieving them from the heavy burden of mortgage and backbreaking interests collected by the landlords and the usurers.” [12] In an attempt to rally the rural poor to its banner, the regime used Decree #6 to excuse landless peasants from paying back all mortgages and debts, while allowing those who owned modest amounts of land to pay back only the original sum on debts and mortgages. [13]

The second phase of the PDPA campaign to mobilize previously unpoliticized segments of the population was launched on October 18, with the publication of Decree #7, “for ensuring the equal rights of women . . . and for removing the unjust patriarchal feudalistic relations between husband and wife and for consolidation of further sincere family ties.” Among other provisions, this decree forbad the exchange of bride-price as part of marriage arrangements, limited dowries to a token amount, stipulated that both parties had to agree to a marriage for it to be legal, and outlawed the practice by which the widow of a man could be compelled to marry one of her husband’s relatives. [14]

Finally, the third major piece of the PDPA plan was a comprehensive program of land reform, which was first discussed in depth in the Kabul Times in an article on July 19. This article claimed that 95 percent of the population subsisted on half of all the arable land, while the other 5 percent of the population controlled the other half. Seventy-one percent of landowners, according to the Kabul Times, owned from one to ten jeribs (one jerib is two thousand square meters), and most of these small landowners were also required to lease additional land from wealthier landowners in order to make ends meet. “Hence the vast majority of the villagers lease land under feudal conditions, i.e., in most cases inputs such as water, seeds, farm tools and implements, chemical fertilizer, means of transportation and the like have to be provided by the owner of the land, and the one who works on the land receives a small portion of the crop, as little as one sixth, in compensation for his hard work.” [15] Although Taraki indicated shortly after taking power that it would take at least two years for the government to prepare the necessary surveys and otherwise lay the groundwork for land reform, the regime decided to push ahead with this program, presumably in response to the first signs of popular dissatisfaction, which appeared over the summer. Consequently, on December 2, the government published its Decree #8, the most important stipulation of which was that no family could own more than thirty jeribs of first-quality land and that no person could mortgage, rent, or sell land in excess of that amount.

Although the government promulgated many decrees in addition to these and promised still more, Decrees #6, #7, and #8 were the base on which the regime made its appeal for popular support, and press organs went to extreme lengths to inflate the success of the programs and demonstrate the general acclaim with which they were greeted. Thus, on October 3, Taraki reported to the Central Committee that 11.5 million landless peasants had been released from “the backbreaking burden of usury and mortgage”; and on October 18 it was announced that, after five months of the revolutionary regime, “millions of peasants were freed from the clutches of moneylenders and at least Afs. [Afghanis] 30 billion was gained by landless peasants or petty landlords.” [16] According to government statistics, eight hundred agricultural co-ops with two hundred thousand participants had also been established. The lands of forty thousand farmers had been surveyed for redistribution. Two hundred houses had been built for agricultural-extension officials, with 136 more under construction. Fifteen hundred kilograms of seed had been distributed. Eleven hundred seventy new orchards and vineyards had been organized. Thirty-seven threshing machines, 380 ploughs, 300 wheelbarrows, one thousand sickles, and two hundred pitchforks had been distributed. Four million animals had been immunized or treated for disease. Twenty-three veterinary clinics had been opened. Two hundred sixty thousand boxes of silk cocoons had been handed out; and two hundred thousand acres of land, thirteen orchards, and seventy-six houses belonging to the Yahya dynasty had been “bequeathed” to people. [17]

The declarations of popular support were equally extreme. Thus, in July, banner headlines announced that “Peasants Hailed Decree No. 6,” and articles throughout that month told how the decree was releasing “landless and petty land holders from the yoke of exploiters and feudals.” In August, it was announced that a Muhammad Wazir of Faryab Province was so impressed with the new regime that he donated all his property to the government, including 150 jeribs of land, 480 sheep, 220 lambs, forty-two large and thirty-seven small goats, fourteen cows and calves, three donkeys, and one horse. [18]

In November, the reception for Decree #7 in Kunar Province was similarly enthusiastic, as “students and local people of Sarkanai staged a march in the streets of that woleswali [district administrative center] carrying the photographs of our beloved and revolutionary leader, shouting revolutionary slogans, hurrah and prolonged clappings.” Government-sponsored rallies on behalf of the first two decrees proved to be mere rehearsals for the launching of the land-reform program in the winter of 1979. Throughout January and February, the Kabul Times published articles on the jubilation of peasants who were receiving their new land deeds and celebrating “chain-breaking” Decree #8. In these articles, in among descriptions of peasants chanting “death to feudalism,” “death to imperialism,” “long live and healthy be Noor Mohammad Taraki,” a now-dispossessed former landlord is quoted as welcoming land reform “because if I lost my lands on the one hand I got rid of all the psychological pressures and torturing engagements on the other hand.” [19]

One typical article with the headline “Now No One Will Flog Me to Work on His Land without Wage, Says Peasant” contained the following description of a grateful recipient of government largesse:

Haji Nasruddin, a peasant from Balla Bagh village of Surkhrod [in Ningrahar Province] said smilingly, “God is with those who are helpless. Consequently the decree number eight has come to our rescue. Hereafter whatever we reap belongs to us. Hereafter no feudal lords or middlemen will be able to cheat us. This all has happened with the attention of the Khalqi state. We the toiling peasants have been delivered forever. Today the government is headed by those who work solely for the benefit, for the welfare of the poor and downtrodden. It is a happy occasion that we the peasants have achieved our cherished desire.

“Now with the six jeribs land given to me I am sure I will become the owner of a decent living and will not die of hunger. Before the Saur Revolution the feudal lords used to loot all our products. The rulers at that time sided with the oppressive landlords. Fortunately the Saur Revolution has destroyed their dreams and they can no longer achieve their ominous goals.”

Juma Gul another peasant from the same village said that [“]all my age has passed in poverty but today I have become the owner of land and I hope to continue the rest of my life with the peace of mind. Hereafter no one will dare flog me to work on his land without wages and I will be the master of my own destiny.” [20]

Throughout the winter and spring of 1979, the government pushed land reform forward and announced on June 30 that the program had been completed, with 2,917,671 jeribs having been turned over to 248,114 households. An additional 151,266 jeribs had been allocated to state farms, and 125,000 jeribs had been assigned to local municipalities and provincial departments. All told, the government claimed to have redistributed a total of 3,193,937 jeribs. [21]

It is difficult to guess where all of these figures came from, or, to be more precise, it is unclear whether the land-redistribution figures published by the government represented actual transactions that took place, if only on paper, or were simply invented. We do know that by the spring of 1979, the government had lost its campaign to mobilize popular support, and it was already fighting just to maintain its bases in some areas of the country. The best explanations for this failure are those that take into consideration the local conditions and the situation in which the regime tried to interpose itself. In Part Two, I provide an in-depth explanation for one area of eastern Afghanistan, but here I want to examine some general matters relating specifically to how the Khalqis formulated the relationship of ruler and ruled and how that formulation was popularly perceived.

When the PDPA came to power, it tried to convince the people of their shared values and common concerns, as well as the fact that the government was the “servant” of the people, but the language used to convey these sentiments was an alien one. It was derived from a Marxist lexicon that had no roots in Afghan culture and that struck no resonant chord in the hearts and minds of the Afghan people. The government premised its appeal on two assumptions: first, that material concerns were foremost in people’s minds and, second, that abstract principles of recent vintage could carry moral force. The failure of these premises, as well as the antipathy widely felt toward the people empowered by Khalqi rule, is illustrated in the following account by a village elder from the region of Khas Kunar on the east bank of the Kunar River, close to the border with Pakistan:

In the beginning, the common people of Afghanistan didn’t recognize the true identity and face of the Khalqis and Parchamis as infidels [kafir] and communists. And in their own slogans they said, “We respect Islam, and this is a government of the working people. Everyone has equal rights. And we will save all the people from poverty and hunger.” The slogans that they used were things like “Justice” [‘adalat], “Equality” [masawat], “Security” [masuniyat], “Home” [kor], “Food” [dodai], and “Clothing” [kali]. . . .

After Decree #7, Decree #8 concerning land reform was announced. Since the population of Khas Kunar is very high and the land is very little, few people had more than thirty-six jeribs of land. Their number reached ten or fifteen. By the most shameful kind of action, they took these people’s land and gave it to others. On the land of each one of these people, they organized a march, and they invited all the uneducated people, as well as the students, clerks, etc., to take part. When the land was dispensed and the deeds signed by Nur Muhammad Taraki were given out, they shouted “hurrah!” and slogans like “Death to the feudals!” “Death to the Ikhwan [Muslim Brotherhood]!” “Death to American Imperialism!” “Death to Reactionaries!” and that kind of thing.

Since the slogans of the people of Afghanistan during happier times were “Allah-o Akbar!” [God is great] and “Ya Char Yar!” [Hail, Four Companions of the Prophet Muhammad], they became very unhappy and said that, in addition to the other deeds of the Khalqis and Parchamis, the fact that they had changed “Allah-o Akbar” and “Ya Char Yar” to “hurrah” was a sign of their infidelity. [22]

For Pakhtuns, the slogans chosen by the Khalqis conveyed little of a positive nature. Justice, equality, and security are loan words that make abstract what Pakhtuns typically feel they already have, and, in their experience, when justice, equality, and security are absent, it is precisely because of government interference in their lives of the sort that the new regime was promising. Similarly, home, food, and clothing, which were generally chanted in rallies as a single phrase (“kor, dodai, kali!”), are words that glorify material things that are morally inconsequential and properly kept within the domain of family and kin.

Likewise, when recalling marches at which people were encouraged to shout such phrases as “Death to the Feudals” and “Death to American Imperialism,” one should keep in mind the difference between the rhetoric of Marxist opposition and the dynamics of tribal opposition that heretofore had held sway through much of Afghanistan. In tribal culture, to boast that you intend to kill someone places you under the burden of that claim. Utterances have consequences, and for one to publicly promise to do that which one does not intend ultimately to do or which cannot be done makes one appear foolish and dishonorable. That is to say, if people do not realize that words have weight and use them carelessly, then they cannot be trusted, for they are clearly unaware of the implications of honor and, as such, are a danger to themselves and others.

Beyond the morally contradictory nature of the slogans themselves, government-sponsored rallies failed to achieve their intended effect for several other reasons. Given the defensive orientation of Pakhtun groups and their longstanding suspicion of government interference in their affairs, the arrival in their community of government representatives promising to help them by taking the possessions of one group and giving them to another was hardly welcomed. Even those who directly benefited from the land redistributions were unprepared to receive government largesse. The problem here was not only that the language used by the PDPA was novel but also that people had not tended to look to the government for benefits and, when they had, they petitioned the government; the government did not petition them.

The approach taken by the regime was unprecedented, and in Pakhtun society the assumption is that unprecedented actions should be treated with circumspection until such time as they can be rendered familiar and unthreatening. Thus, when strangers came and encouraged all the poor people in a community to come together as a united body shouting slogans, the need for circumspection and a unified front against the outsiders increased—regardless of the offers and promises being made. In this way, public rallies and marches backfired, especially in rural areas and small towns, and they created the opposite effect from what was intended. Instead of loosening the ties that bound wealthy and poor, government attacks on the “feudal class” encouraged a defensive solidarity among the group as a whole and evoked sympathy for the wealthy, who came to be seen as victims of a more immediate oppression than the abstract oppression invoked by the government. [23]

Another issue to consider is the government rallies themselves as a form of public performance. These events usually involved the presentation by provincial and sometimes national officials of newly printed land deeds to tenant farmers and formerly landless agricultural laborers who were brought to the center of the town or village and handed placards praising the government and damning its enemies. Most newspaper photographs of these events show groups of newly enfranchised farmers carrying shiny shovels and slogan-covered placards while standing or marching in parade-ground formation. However the government intended these performances to be perceived, local people generally viewed them as an embarrassment and a disgrace. Nothing in their experience had prepared them for such events, the symbolic construction of which was interpreted as contradictory to modes of self-presentation esteemed in Pakhtun culture. Thus, for example, such stock performance devices as the unison shouting of praise for the revolutionary party while marching in formation were viewed by people as acts of public humiliation that violated their sense of individual initiative and control. For generations, many Pakhtuns had resisted service in the Afghan army (except when they were allowed to retain their tribal character by serving as militia units) because the discipline demanded by the army ran counter to the cultural valorization of individual autonomy. Wearing a uniform, marching in formation, and obeying the commands of officers were demeaning to Pakhtun sensibilities. However, at least such parade-ground displays were performed at a distance from home, and while it entailed a sacrifice of personal control, military discipline did have the saving virtue of being oriented toward success on the field of battle, an objective Pakhtuns understood and valued.

Government rallies, however, were events staged in the presence of the local community and required individuals to comport themselves in front of their peers in order to glorify an alien institution—the Khalq party. In tribal culture, the only kind of public chanting one traditionally heard was of a religious nature, and the only occasion when individuals lined up in formation and collectively performed orchestrated ritual actions was when they submitted to Allah in public prayer. That people were forced to perform other sorts of collective gestures and utter novel phrases in order to glorify an entity other than Allah made apparent a contradiction that doomed the party’s efforts to enlist popular support. Whatever views people might have had about the inequalities of wealth and power in their communities, their belief in Islam was sacrosanct, and once it had been demonstrated to them that the government authorities wanted them to perform in a manner that placed secular principles above religion, their loyalty could not be reclaimed.

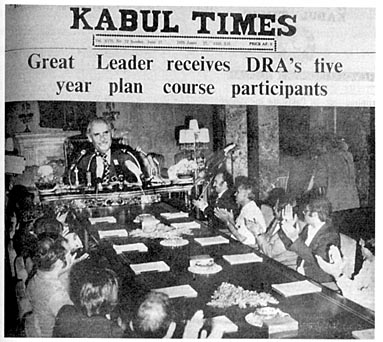

Another example of how the Khalqis lost the confidence and respect of the people was their construction of a cult of personality around President Taraki that transformed him from a “true son of the soil” into a grotesque socialist icon. The first signs of this cult appeared in the early summer after the coup, when headlines began referring to Taraki as “Great Leader.” (For example, the June 27th headline of the Kabul Times announced, “Great Leader Says, We Wish to Ensure Our People a Happy and Prosperous Life.”) The published biography examined in the preceding chapter was another milestone in the cult’s development, as was the announcement on December 9 that Taraki’s birthplace would be converted into a national museum with a special road, three large bridges, and twenty-five smaller bridges constructed to provide public access at a cost of 2.5 million Afghanis. Later, in April, the newspapers proclaimed that, for the first anniversary of the Saur Revolution, Taraki’s birthplace “will be illuminated and decorated with photos of Great Leader of Khalq, national red flags, revolutionary slogans and coloured bulbs.” [24]

One of the more bizarre manifestations of the Taraki cult was the publication in the government press on June 17 of doctored photographs in which the larger-than-life image of Taraki appeared, seated at his desk. In front of him, arrayed around a table, government functionaries, dwarfed by Taraki, are clapping and smiling in the presence of the benevolent “Great Leader” (Fig. 7). [25] On June 18, the same sort of photo was published, this time crudely depicting a giant Taraki with representatives from the Achikzai and Noorzai tribes, Baluchis from Qandahar, and elders from Badghis Province. The retrospective irony here is that as the manifestations of the cult of personality became increasingly outlandish and bizarre, Taraki’s actual authority was steadily being sheared away by his erstwhile disciple Amin, who in all likelihood was the principal author of the Taraki cult and most certainly the agent of Great Leader’s demise. It is interesting to examine this photograph next to those of earlier leaders. Taraki was the one leader who actually rose up from the masses to lead his country. The other leaders whose photographs I have included—Habibullah, Amanullah, Daud—all inherited their right to rule. Taraki pinned his right to rule on the people, the “people’s party,” and his own humble origins. Yet he was the one who ultimately—whether because of insecurity or secret vanity or the manipulations of others—attempted to inflate his stature, thereby only accentuating his limitations and inappropriateness as a ruler.

7. President Nur Muhammad Taraki (Kabul Times, June 18, 1979).

The same could be said as well of those who flocked to the party banner and were taken on as mid- and low-level government officials. Time and again, Afghans have commented to me about the quality of the people who came to power with the revolution in the local, district, and provincial branches of administration. When the Khalqis came to power, they brought with them a new style of rule, what they called “a people’s government [that] doesn’t belong to anybody.” The new regime, they declared, was “not a hereditary government run by a number of traitorous Sardars (princes); rather those who run your people’s government at present are millions of honest, courageous and patriotic people of Afghanistan . . . your best patriotic sons from every tribe and region in the country.” [26] What this meant in practice was that considerable power was exerted by local officials, many of whom had been students before the revolution and some of whom had been recruited and trained by Amin himself when he was a teacher and principal at the teacher-training college in Kabul.

As in many developing countries, teachers in prerevolutionary Afghanistan were poorly paid and had little clout in the communities in which they served. Even if they were respected for their learning, they were often outsiders, and, like mullas, they tended to be viewed in a patronizing light because of their dependent status and the fact that their jobs required that they spend most of their time in the company of children rather than adults. One of the accusations most commonly leveled at these teachers once they ascended to positions of authority under the new regime was that they were more concerned with Marxist ideology than with the realities of the social milieus in which they found themselves. Perhaps because of the patronizing treatment and limited respect they had received before the revolution, they did not tend to make much effort to modulate directives coming out of Kabul to local sensibilities and sensitivities, and people came to resent what they considered their high-handed attitude.

Likewise, many informants claimed that after the revolution the party attracted opportunists who exploited the power given them. In the words of one man from Paktia Province, those who first joined the party after the revolution were the kind who “had begun school but not finished, who had wanted to become bus drivers but only managed to become ticket collectors. They started off to work in the Emirates but only made it as far as Iran.” One oft-heard claim is that the party was so short of members when it took power that it would take anyone willing and able to spout back party doctrine and sport the droopy mustaches then in favor among Khalqi supporters. Men from good families and with established reputations would never humiliate themselves in this way, but individuals from the lower strata of society had no family or personal reputation to disgrace and much potentially to gain by association with the party. In the words of Shahmund, the Mohmand elder quoted in the previous chapter, “the sword of real iron cuts.” Men from poor families were unlikely to manifest nobility or to show abilities that had previously gone unnoticed just because they had been elevated to positions of power. In the view of most Afghans with whom I have talked, this type of individual—no-accounts from ignoble families—flocked to the government when the PDPA took power, and not surprisingly they were only too happy to carry out the regime’s campaign against “feudal exploiters” by debasing the old elites who had previously held pride of place over them.

If these elites had been genuinely resented by the less-wealthy and less-prominent strata of society, then the treatment meted out to them by government officials might have been appreciated or at least tolerated. However, in most parts of Afghanistan in the late 1970s, differentials of wealth, while present, were not extreme, the economy was not heavily monetized, and investment opportunities were scarce, all of which meant that more prosperous landowners were generally not taking their profits out of the area. To the contrary, it was still most common for the wealthy to reinvest their profits within their communities through guesthouses (hujra) where they fed their allies, friends, kinsmen, tenant farmers, and potential political supporters. [27] The continuing involvement and investment of the wealthy in their communities, coupled with local beliefs about the sanctity of private property and the generally poor opinion people had of Khalqi officials, meant that in most locales people rejected out-of-hand government efforts to enlist their support.

Enemies of the People

When the PDPA regime first took power in April 1978, the principal threat with which it was concerned was subversion from abroad. Thus, in the first issue of the Kabul Times published after the coup d’état, the regime lashed out at “the mass media of foreign reaction,” which was spreading false propaganda against the “triumphant revolution of Saur Seven.” The false foreign-press reports blasted by the regime labeled the revolution a coup d’état “launched under the leadership of the communist party of Afghanistan with the help of this or that foreign country.” The government’s position was that “the revolutionary stand of Seventh Saur is the beginning of a truly democratic and national revolution of the people of Afghanistan and not a coup d’état.” In similar fashion, the regime railed at “international reactionary circles” that “shamelessly lie that thousands of our patriots were either killed or executed in the course of the revolution and that one of the great religious figures has been executed or that the revolutionaries had acted in contravention of the principles of human rights, the Islamic religion and our national traditions.” At the same time the government was focusing primarily on the threat of subversion by reactionary forces abroad, the Interior Ministry also warned citizens that “in such a revolutionary situation a number of profiteering, wicked, intriguing, subversive and anti-revolutionary elements [might] appear on the scene posing themselves as revolutionaries and consequently cause inconvenience and indulge in threatening and provoking of compatriots and social disruption.” [28]

In the beginning, no one in the PDPA leadership knew precisely where the greatest “antirevolutionary” threat might lie. Perhaps surviving members of the Daud regime would rise up to challenge the legitimacy of the Taraki government. Perhaps the former king, Zahir Shah, or those close to him, would mount an attack from abroad, as Zahir Shah’s father had done when Bacha-i Saqao had taken the throne in 1929. Then again, there was the threat of subversion from within the party itself; this threat was dealt with summarily in July, when the leadership of the Parcham wing was sent abroad. Despite these uncertainties, however, both historical precedent and personal experience suggested to the leadership that their greatest threat would come from forces representing or claiming to represent Islam.

Amir Abdur Rahman, after all, had had to deal with hostile religious leaders, the Mulla of Hadda prominent among them, throughout his reign; and his grandson, Amanullah, had finally been undermined by a religious/tribal coalition centered around various religious figures, principally the Hazrat of Shor Bazaar. [29] Since Amanullah’s downfall, religious leaders had generally been quiescent, but a new generation of secularly educated Muslim activists had risen up in Kabul at roughly the same time that the Marxist parties had begun their activities. Amin, in particular, would have been wary of this threat, for the students he recruited in the late 1960s and early 1970s had regularly faced off against the Muslim student activists in classrooms, in cafeterias, and on the street during sometimes bloody political demonstrations. For much of his tenure in office, President Daud—to his ultimate misfortune—had been more afraid of Muslim activists than of Marxist ones, and he had been responsible for imprisoning many Muslim student leaders. However, some had escaped his dragnet and had taken up residence in Pakistan, where they had been receiving assistance from the Pakistan government of Prime Minister Zulfiqar ‘Ali Bhutto and were preparing themselves for battle against the new regime.

Given his leftist sympathies, Bhutto might have been willing to work with the PDPA and revoke his support for Islamic opposition leaders who had found a safe haven in Pakistan, but by the time of the Saur Revolution, Bhutto was out of power, and the more devout President Zia ul-Haq had taken his place. Whatever slim chance the PDPA regime might have had of reaching an accord with Pakistan over the removal of the still small and ineffectual Islamic parties on their soil was eliminated when the Kabul government began inviting Pakhtun tribes from the Pakistan border areas to meet Taraki. At various times since the founding of Pakistan, the Afghan government had contested Pakistan’s authority over the border areas, most memorably in the late 1950s, when the two countries broke off relations and closed their borders. Consequently, the Khalqi government’s decision to court the cross-border tribes must have been taken as an insult and threat, particularly after it announced its support for an independent Pakhtun state along the frontier. [30] Bhutto had first given refuge and assistance to the Muslim student leaders because of President Daud’s backing of “Pakhtunistan.” Daud had recognized the risk involved in continuing this policy over Pakistani objections and had backed off, but the PDPA made the decision to again embrace Pakhtunistan, presumably to help defuse tribal opposition to the regime. In so doing, however, it guaranteed the survival of the ultimately more dangerous Islamic movement, without in any appreciable way bolstering tribal support.

The regime tried to counter the still labile Islamic threat by reiterating its respect for Islam and equating the Islamic principles of “equality, brotherhood and social justice” with the guiding principles of the regime. [31] Likewise, at the beginning of Ramazan, which fell in early August in the year of the revolution, the regime arranged for the traditional recitation of the Qur’an and prayers to be held at the People’s House. An article in the Kabul Times about this event noted that while in the past Ramazan prayers had been held in only 164 mosques in Kabul, this year they would be performed in 182. [32] However, at the same time that the regime was trying to affirm its Islamic beliefs, it also had to acknowledge the developing threat represented by Muslim extremists based in Pakistan. One example of the regime’s manner of dealing with this threat can be seen in Taraki’s address of August 2 to military officers, which was discussed in the previous chapter. In this speech, Taraki provided his first extensive commentary on the rising threat posed by the Islamic resistance movement:

When our party took over political power, the exploiting classes and reactionary forces went into action. The only rusty and antiquated tool that they use against us is preaching in the name of faith and religion against the progressive movement of our homeland. The bootlickers of the old and new imperialism are treacherously struggling to nip our popular government in the bud. They think that since we took over power in 10 hours, they would, perhaps, capture it in 15 hours. But they must know that we are the children of history and history has brought us here. These agents of international reaction ought to know that by acting in this way they are banging their heads against a brick wall. These agents of imperialism who plot under the mask of faith and religion have not begun this task recently. They have been busy conspiring against progressive movements in this fashion for many long years. You will remember the crimes they committed in various forms in Egypt and other Arab countries. Now their remnants and pupils existing in Afghanistan are acting under the mask of creed and religion in a different fashion. They ought to be uprooted as a cancerous tumor is from the body of a patient in a surgical operation. [33]

While promising that the government and party were “so fully in control that they will not give them a chance . . . to carry out their evil deeds,” Taraki’s statements demonstrate that already at this early date the resistance was making an impact that the government couldn’t ignore or pretend was insignificant. Taraki’s approach to this threat though was predictable. He emphasized that those working against the regime were—like Nadir before them—“agents of imperialism” out to undermine Afghan independence. Echoing the propaganda of earlier regimes against Muslim opponents, Taraki claimed in this speech that the regime’s enemies were not truly inspired by Islamic principles but simply “plot under the mask of faith and religion.” In later speeches, he embroidered this allegation by referring to the Islamic forces arrayed against him as “made-in London maulanas [religious scholars]” [34] and as “the spies of the farangis” who “have spread fire in Afghanistan several times but this time the people of Afghanistan have spread fire against them.” [35] Taraki was referring here to the overthrow of Amanullah, which many Afghans (including some who took up arms against the amir) suspected was secretly instigated and supported by the British government in India. The fact that the British had been absent from the scene for more than thirty years when the regime made its accusations against “made-in London maulanas” would seem to be evidence either of the enduring power of British imperialism as a symbol of evil in Afghan politics or of the inability of the regime to come up with more effective rhetorical ammunition to counter the growing threat.

By the fall of 1978, antigovernment violence had risen dramatically, and the regime announced that it was “declaring jihad” against “the ikhwanush shayateen”—the brotherhood of Satan. Drawing attention to the philosophical connection between the Muslim activists who had gotten their start at Kabul University and the Ikhwan ul-Muslimin(the Muslim Brotherhood) in Egypt, articles in the state-run press condemned Egyptian radicals for hollowing out copies of the Qur’an in order to conceal guns inside and accused Afghan “Ikhwanis” at Kabul University in the early 1970s of having torn up copies of the Qur’an and then blaming leftist students as a way of defaming their opponents. Anti-Ikhwan articles appeared throughout the fall and winter, climaxing in an article on April 1, which stated that “these ‘Brothers of Satan,’ these Muslim-looking ‘farangis’ clad in white but not able to cover their black faces, these false clergymen who have been inspired by London and Paris . . . they are actually ignorant of Islam as they have only learned espionage techniques in London. They wish our people to abandon their religion and be marked with a seal from London.” [36]

The PDPA’s decision to declare jihad against its enemies can be taken as a measure of its desperation after only half a year of rule, especially given the mixed success of state-sponsored jihads in Afghanistan. In 1896, as the Mulla of Hadda and other religious leaders were stirring up trouble against British posts along the frontier, Abdur Rahman had published and distributed among the border tribes a pamphlet in which he asserted—with appropriate Qur’anic citations—that only a lawful Islamic ruler could declare jihad. [37] With his unerring eye for subversion, Abdur Rahman recognized that the activities of the mullas, though directed against his neighbors and not his own regime, could nevertheless embolden the more fractious among them to redirect their efforts against the Afghan state and to claim religious justification for doing so. The anticolonial uprisings of 1896–1897 ultimately failed to achieve their objective of forcing the British out of Peshawar and the frontier, but they did set the stage for a continuing dispute between the state and Afghan religious leaders over who had the right to raise the banner of jihad.

This dispute bubbled up again in 1914–1915, during the reign of Amir Habibullah, when disciples of the now-deceased Mulla of Hadda again agitated for holy war against Great Britain. Habibullah resisted these efforts, on the same grounds set forth by his father, but shortly after his ascension to the throne in 1919, Amir Amanullah allied his government with the religious forces that had long been urging an attack against British bases along the border. Though he disagreed with religious clerics on almost every other matter, Amanullah had long shared their desire to curtail British dominance in the region and had futilely urged his father to declare war to achieve this end, undoubtedly also recognizing the opportunity provided by such a war to consolidate his own rule in the wake of his father’s assassination. The hoped-for war began on May 15, 1919, with an address by Amanullah at the central Id Gah mosque in Kabul; these are some of the words that he is purported to have spoken on that day:

The treacherous and deceitful English government . . . twice shamelessly attacked our beloved country and plunged their filthy claws into the region of the vital parts of our dear country which is the burial ground of our ancestors and the abode of the chastity of our mothers and sisters, and intended to deprive us of our very existence, of the safety of our honor and virtue, of our liberty and happiness, and of our national dignity and nobility. . . . It became incumbent upon your King to proclaim jehad in the path of God against the perfidious English Government. God is great. God is great. God is great. [38]

In this declaration of war, Amanullah hit all the notes guaranteed to arouse Afghan indignation. The British were not depicted as an honorable adversary but as bestial, dirty, and animal-like in their method of assault. They were the attackers, and in their attack they violated the inviolable: the sanctity of the community, defined here in culturally coded terms as “the burial ground of our ancestors” and “the abode of the chastity of our mothers and sisters.” At stake here was more than land; it was honor, liberty, and dignity—values that Afghans esteem above all other virtues. Finally, Amanullah framed his response in religious terms as a jihad, a struggle on behalf of Islam, and he concluded with the traditional rallying cry of allah-o akbar (God is great). Though in later years the war became known in more nationalistic terms as the jang-i istiqlal (the war of independence), it was framed at the time as a religious jihad, and Amanullah relied heavily on religious leaders to extend his message into the tribal areas. At his urging, the Hazrat of Shor Bazaar and several family members, who were well-known Sufi pirs (masters), accompanied the troops to Paktia, where many of their disciples lived, and convinced the local tribes to join the fighting. Similarly, in the eastern (mashreqi) border areas of Ningrahar and Kunar, disciples of the Mulla of Hadda served as Amanullah’s messengers and preached to their followers the virtue of fighting against the infidel British.

The war was ultimately short-lived and inconclusive in its results, but the Afghans managed to achieve one significant military victory, and the British, still depleted after the First World War, agreed to a cessation of hostilities and diplomatic terms that the Afghans viewed as favorable to their status as an independent nation. More important to the discussion at hand, the war showed the potential advantage to a ruler of using the terminology and apparatus of religious jihad for his own ends. Amanullah’s ultimate downfall, however, also demonstrated the risks of this strategy, for in lending his support to religious leaders like the Hazrat of Shor Bazaar, he gave them a stage that helped to energize and strengthen their own standing with the people. Consequently, when he began his controversial reform program, the Hazrat was well positioned to oppose him and rally the same tribesmen against Amanullah whom he had earlier mobilized against the British.

Taraki’s use of jihad to check the Muslim opponents of his regime proved ineffectual by comparison with Amanullah’s use of the same rhetoric to oppose Great Britain, in part because Taraki was directing his rhetoric not at a foreign enemy but at other Afghans. At the same time, given that he had come to power not through any recognized set of procedures but by the violent overthrow of the previous regime, Taraki was not in a strong position to argue, as Abdur Rahman had been able to do, that he alone had the right to declare jihad. His situation was even further compromised by his prior rejection of the title of amir (they being the ones who are named in the Qur’an as entitled to declare jihad) in favor of such Soviet-flavored titles as general secretary (umumi munshi)of the party and president (ra’is)of the Revolutionary Council. Of the various honorifics attached to his name, none made any reference to Islam or put him in a position to wield religious authority, which he had anyway eschewed in his oft-repeated assertion that he owed his power to the party, not to God.

Likewise, there had never been a religiously sanctioned installation ceremony when Taraki had come to power. No religious figure had ever followed the time-honored practice of tying a turban around or placing a crown on Taraki’s head or otherwise symbolizing religious ratification of his rule. The only support the PDPA regime had managed to secure was from a group of unrepresentative and much-maligned government-employed clerics. The better-known religious leaders had been conspicuously absent from official ceremonies and news accounts, and rumors had quickly spread that a number of well-known religious figures had been arrested after the revolution. Among these rumors was one concerning Muhammad Ibrahim Mujaddidi, the son of the same Hazrat of Shor Bazaar, who had played a major role in overthrowing Amanullah. Although not conspicuously political like his father, Ibrahim Mujaddidi was said to have been arrested, along with most of his family, on orders from the Khalqi leadership. No one knew for certain what happened to the Hazrat and his family, but after his disappearance people came to believe that they had all been executed on the orders of Taraki or Amin (or both). In time, those rumors would be verified, though no one has ever been able to prove—as rumors have indicated—that the family was bound and gagged and placed in tin shipping trunks, that targets were affixed to these trunks, and that soldiers who were ignorant of who or what was inside were ordered to use the trunks for firing practice.

In their efforts to check the spread of popular opposition, the regime was hobbled more than anything by its own terminology. From the beginning, it claimed to be different. It was a party of workers and toilers who had come to power not through dynastic succession or even dynastic strife, both of which had precedents in Afghan history, but through a revolution (inqilab)—a “turning around” from what was normal to something altogether out of the ordinary. For people who felt themselves to be oppressed by and alienated from their society’s institutions, who took no solace in what the culture offered them, and who saw no hope in the present or the future, the language of revolution, of overturning the existing order for something unknown and untried, might prove attractive. But most Afghans—whatever their economic circumstances—were not so radically estranged from their social institutions and their universe of cultural signs and signifiers that they found the language of revolution compelling. If anything, it smelled of trouble, of sanctioned disorder, which in the universe of Islamic belief amounted to fitna—sedition, nuisance, trouble, mischief. In the Qur’an, believers are warned against the dangers of fitna in a passage that urges the followers of Muhammad to expel their disbelieving kinsmen from Mecca because “fitna is worse than killing. Fight them until there is no more fitna and the religion of God prevails.” [39]

In the winter and spring of 1979, the Khalqi regime went more and more on the defensive, attempting to counter charges by the “farangis and their puppets” that they were burning mosques (“We have never burnt the mosques but we have constructed them. We have painted them and decorated them well.”) and confiscating sheep and arresting women (“We will neither take anybody’s sheep nor anybody’s woman—who is our sister. She is our honour, and we make efforts to defend them every moment.”). [40] In the summer of 1979, the government tried to substantiate its claim that the resistance parties were the enemies of Islam by holding a press conference at which four residents from a village in the Zurmat district of Paktia Province recounted separate attacks on their villages by “Ikhwanis” who “were burning the Holy Koran and bombing and destroying the mosques. Those who were trapped in their criminal onslaught begged them, Holy Koran in hand, but Ikhwanis ignoring the sacred religious book of Islam, continued their ominous actions.” [41]

During this same period, in a further effort to shore up its support, the regime began a second series of daily meetings with elders from the Pakhtun border zone and other areas with a history of antistate activity, such as Kalakan and Mir Bachakot north of Kabul. The government-sponsored religious organization, the Jamiat ul-Ulama Afghanistan (Society of Afghan Clerics), also trumpeted its support for the regime, declaring that it was lawful according to Islamic law for the government and its supporters to “kill Ikhwanis” in the prosecution of its jihad against enemies of the revolution. [42] Regardless of these efforts, however, the battle against the resistance was going more and more badly. Some reports indicate that Amin even tried to negotiate a power-sharing agreement with Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, the leader of Hizb-i Islami Afghanistan (Islamic Party of Afghanistan), one of the earliest and best-organized resistance parties. But a deal never emerged, and the regime’s reputation continued to plummet amid rumors of arrests and nighttime executions and stories of civilian massacres.

Other rulers before Taraki had also been known for their ruthless suppression of enemies, notably Abdur Rahman, who blew enemies of the state from the mouth of the noon cannon in Kabul and locked up robbers in iron cages suspended on tall poles and allowed them to starve to death in public view so that passersby could reflect on the fate of those who stole on the king’s highway. Nothing the Khalqis did ever approached Abdur Rahman’s punishments in terms of conspicuous excess, but they nevertheless inspired revulsion: first, because general understandings of the acceptable limits of behavior had changed; second, because of their secretiveness; and, third, because many of their victims were known to be innocent of any offense against the regime. For the residents of Kabul and other cities, the regime’s practice of arresting people under cover of dark and not allowing any communication between those accused and their relatives was the source of the most resentment and fear. [43] For those in the countryside, the source of fear was the possibility of being held responsible for antigovernment violence. The most notorious of such retributions was the massacre at the village of Kerala in the Kunar Valley, which occurred in April 1979 and resulted in the deaths of more than one thousand unarmed males. [44]

If the people needed evidence that the Saur Revolution had introduced not needed reform but an era of irreligious disorder, then mass arrests and incidents like the massacre at Kerala provided it and eroded the little store of credibility the regime had built up with the people. And while Taraki and Amin might have been oblivious to this fact or at least still hopeful that their fortunes might change, their Soviet patrons were less sanguine. They viewed the progressive disablement of the Khalqi regime with mounting dismay and horror, particularly the fact that the popular movement gaining the upper hand against their clients in Kabul was becoming increasingly identified with Islam, a force they knew very well could be revived in their own Central Asian republics. The Soviets were not about to let a sympathetic government fall to a popular insurrection. Better to give the lie to the rhetoric of peasant revolution against feudal oppression—a rhetoric that had been on shaky ideological ground to begin with in Afghanistan—than allow a well-meaning, if incompetent, government to fall to a minimally organized and undersupplied insurgency.

Conclusion

From an orthodox Marxist point of view, the PDPA was ahead of its time, trying to create a socialist revolution in a society that was still solidly feudal and a generation or more from achieving a full-blown capitalist economy. While it is doubtless the case that the party got ahead of itself, paying more attention to the ideological blueprint than to the complex realities of the society that blueprint was designed to transform, it is also true that the regime had an opportunity to stay in power and implement incremental change had they had the strategic sense to do so. Many of the mistakes the Khalqis made were avoidable; indeed, many were repetitions of the errors made by Amanullah fifty years earlier and should have been apparent to them as such. Of these, several stand out, such as the decision to highlight women’s rights as a banner issue immediately after coming to power. The education, empowerment, and politicization of women promised to be a multigenerational struggle. It would not be accomplished in six months, and from a strictly pragmatic perspective the enlistment of women into the coalition—even if it could have been carried off—offered little practical political advantage to the regime. Contrary to what the Khalqis seem to have believed possible, women were not likely to become a “surrogate proletariat” any time soon, and if Amanullah’s experience offered no other lesson, it should have been that interference in domestic affairs was a tripwire issue for conservative elements in the country. [45]

Similarly, one wonders at the decision by the regime to embrace the red regalia of Soviet rule, especially after its leaders had wisely distanced themselves from the Soviets in their first few weeks in office. Foreign interference is the other hair-trigger issue for Afghans, whose history is punctuated and defined by its wars with Great Britain. Adoption of red flags and other Soviet-inspired emblems was doubly troubling for Afghans in that it brought to mind their own history and mythology of foreign intervention, while also invoking the dismal specter of the Bolshevik conquest of Bukhara and other Central Asian polities. In the same vein, the use of Soviet-style rhetoric was another crucial mistake, for rural Afghans, who never read newspapers and rarely saw government insignia, did listen to the radio and recognized the resemblance between the rhetoric coming from Kabul and that from the local-language radio stations broadcasting from Soviet Central Asia. A final error on the part of the Khalqi regime—as discussed in this chapter—was the symbolic mismanagement of its reform platform, which succeeded only in alienating those it intended to win over. Viewed in this light, the Khalqis failed not just because of bad policies, inept leaders, or dreadful timing; of at least equal importance was the regime’s rejection of the symbolic codes of Afghan society and the wholesale importation of an extraneous set of codes borrowed from Soviet Marxism. Given Taraki’s career as a social-realist writer steeped in the minutiae of daily life and the regime’s identification with peasants and workers, it is surprising that he and his partisans would be so disdainful of the sensibilities and sensitivities of the people they hoped to lead.

The only viable explanation for this blindness is perhaps that they were so seduced by the promises of ideology that they lost sight of the social realities around them. Taraki, Amin, and the lesser lights of the party were in the grip of a belief system that led them to believe in the inevitability of what they were doing, and their early experiences only confirmed that message. Thus, when the revolution came, it all fell into place so easily. The once terrifying, glowering Daud and his all-powerful ship of state slipped beneath the waves with barely a groan or a shudder. Few mourned their passing, and none of those left from the royal lineage had the stomach or talent to challenge the usurpers. As for the people, they had experienced a coup d’état before. Daud himself had conditioned them to this reality of modern life, and no one seemed to bother much when it happened again. In the eyes of the Khalqi leadership, the revolution had gone as planned. Really, it had gone better than they ever could have hoped, and their Soviet mentors were right over the border, eager to lend their support. What need then was there for caution? Taraki had been proven a prophet when the first phase of his “short cut” to revolution had gone off without a hitch. All that remained was to complete the process by incorporating the people. What the Khalqis forgot was that the people were still by and large very much in the grip of the old ways; among other things, they were willing to abide changes in Kabul only as long as the new rulers kept their distance and didn’t try to alter the time-honored rules of relationship. Taxes were a recognized part of that relationship, as were schools, conscription, and the punishment of crimes; interference in domestic arrangements and other cultural practices was not.

In violating this basic tenet of governance, the Khalqis unleashed a firestorm of popular protest. That much we know; but less commonly remarked on is the role of the regime in helping to ensure that the popular insurgency took on a religious cast. This was the final and in some ways most lasting mistake of Taraki and Amin, for in focusing as they did on the threat of the Islamic elements of the insurgency they helped to define the ensuing conflict in Islamic terms. In retrospect, this seems almost inevitable, but at the time of the coup d’état, Islam appeared to be moving in the direction of many Western religions: it was becoming a matter of personal belief rather than of social or political consequence. [46] We know now what we didn’t know then—namely, political Islam, marching in competitive lockstep with Marxism, had been gaining a constituency in the schools and military, and radical Muslim parties had been making their own plans to take power for some time before the Marxist revolution. However, these efforts, like those of the Marxist parties, were confined to interstitial institutions such as schools and the military and were not widespread in the society at large.

As discussed in Chapter Six, efforts by the proto–Hizb-i Islami party to spread its message of radical Islam to the general population had been conspicuously unsuccessful. People were not interested in supporting radical Islam any more than they were interested in radical Marxism. When the Marxists defied the odds and took power, however, they immediately assumed that their greatest threat would come from their old rivals, the Islamists, with whom they had often butted heads on campuses and in army units. They failed to recognize that their rivals had the same problem they did of mobilizing ordinary people to their cause. In April 1978, the Islamic parties were economically impoverished and politically marginalized, and, as will be seen, they played a relatively minor role when insurrections broke out that first summer. But that wasn’t the way the Khalqis saw it. In their myopia—their vision still obscured by the covert campus and cadre struggles of the late 1960s and early 1970s—the hand of the Ikhwanis was behind all their troubles. Or maybe they knew that the opposition to their efforts was more broadly based than they were willing to admit publicly, and they hoped to limit and ultimately defame the popular insurgency by associating it with the heretofore unpopular Islamic student movement. If that was their strategy, however, it backfired, for in highlighting the role of the Ikhwanis and demonizing them as “brothers of Satan,” they were putting a national spotlight on a movement that at the time was little known outside Kabul and giving it a prominence that would eventually translate into greater public visibility and material support from foreign governments eager to aid the anti-Marxist cause. Thus, just as the Khalqis mishandled the symbolic apparatus of power, thereby alienating those they sought to woo, so their maladroit rhetoric also helped to empower enemies who were as estranged from any significant base of popular support as the regime itself.

Notes

1. From a proclamation by Amir Abdur Rahman; quoted in Edwards 1996, 78.

2. Quoted in Poullada 1973, 60.

3. On unveiling and other symbolic changes undertaken by Amanullah, see ibid. and Gregorian 1969.

4. For an account of the twisted tale of Nadir’s assassination, see Dupree 1980, 474–475.

5. Nur Muhammad Taraki addressing a delegation of elders, June 5, 1978; quoted in FBIS, South Asia Review, vol. 5, June 6, 1978.

6. Two mutually comprehensible dialects of Pakhtu are spoken in Afghanistan. Pakhtu is spoken in the eastern part of the country; Pushtu is spoken in the south and west and was the dialect used by the royal family. The speakers of this language are referred to variously as Pakhtuns, Pushtuns, and Pathans.

7. Transcript of a Taraki press conference, Kabul Times, May 13, 1978. Taraki speaking to Behsud and Wardak elders, July 11, 1978; quoted in FBIS, South Asia Review, vol. 5, July 25, 1978.

8. See Stewart 1973 and Poullada 1973.

9. An article in the May 6, 1978 issue of the Kabul Times announced that “the people in different areas of Tirah in Pashtunistan . . . have wished for the health of Noor Mohammad Taraki,” along with residents of Sultani Maseed and Waziristan in “Pashtunistan.” The next day, elders from Shinwar, Utmanzai, Ahmadzai, Wazir, Daud, Beitni, Masid, Karam, Wazir, Khyber, Mangal, Bangash, Nawi, and Turi were all said to have praised the new regime, while Taraki met with more elders from other border tribes: Atmerkhel, Khwajazai, Khogakhel, Utmankhel, Mohmand, Kukikhel Afridi, and Ahmadzai Wazir.

The May 17 Kabul Times published separate photographs of Taraki and tribal elders from Ahmadzai and Wazir; Mohmand, Utmankhel, and Bajawar; and Afridi and Afridi Tirah.

Similarly, on May 21, more pictures appeared of Taraki with leaders from the Wazir, Masud, Daur, Madakhel, Pari Zamkani, Shinwar, and Taraki tribes. On May 22, a photo was published of Taraki with elders from the Zadran and with other Paktia elders, along with a second photo of him with elders from Badakhshan and Qandahar.

10. Kabul Times, May 20, 1978.

11. These meetings picked up again the following year, as antigovernment violence increased. From late April through November 1979, there were successive waves of meetings with ulama (religious authorities) and tribal elders, mostly from Paktia and Kunar, as well as Kohistanis from specified areas such as Mir Bachakot, Kalakan, and Panjshir—all famous for their past involvement in antigovernment insurgencies. After Taraki’s assassination, in late September 1979, Amin staged a new round of meetings with tribal elders from both sides of the border.

12. Kabul Times, July 17, 1978.