Bharthari and Gopi Chand

I turn now to a closer examination of the particular origins of Bharthari and Gopi Chand. For Madhu Nath, both tales are part of a unified, integrated repertoire. The two are linked not only in the similar patterns of their stories—both are kings who turn yogi—but genealogically, as sister's son to mother's brother (see figure 1). Indeed the janmpatri of Bharthari reports the birth not only of Bharthari but also

[4] Guru Guga's life story is little known in Madhu Nath's area of Rajasthan but is found elsewhere in that state as well as in Uttar Pradesh and Punjab (Kothari 1989; Lapoint 1978; Temple 1884, 1: 121–209, 3:261–300).

[5] For example, in the Rajasthani Pabuji epic one character, Harmal, turns yogi in order to complete a dangerous journey and another, Rupnath, is raised as a renouncer but uses his power to support a battle for family vengeance (Smith 1986, 1991; Blackburn et al., eds. 1989, 240–43). In the Punjabi Hir-Ranjha tale (Shah 1976; Swynnerton 1903, 3–67; Temple 1884, 2:507–80) and in the ballad of Malushahi and Rajula from Himalayan Kumaun (Meissner 1985), frustrated lovers become yogis in reaction to the hopelessness of their romantic quests but also in order to further these quests.

[6] Van Buitenen's classic essay on the Vidyadhara hero in Sanskrit stories (1959) made this point; see Lynch 1990 for some reformulations. See also Kolff 1987 for a very interesting and comprehensive discussion of temporary renunciation as an important aspect of the Rajput warrior's identity.

of Manavati, Gopi Chand's mother; and the end of Gopi Chand's tale finds him splitting the fruit of immortality with his uncle. This link between the two renouncer-kings is posited not only in Madhu Nath's stories but throughout most of popular Nath lore. The two are familiarly referred to as a unit: mama-bhannej or "mother's brother-sister's son."

For Madhu and his audience, the stories of Bharthari and Gopi Chand, performed in a familiar dialect, belong to local lore. My original approach to interpreting these tales was a parochial one: I wanted to understand their meanings for Ghatiyalians. But even that limited endeavor necessitated broadening my horizons. For example, Gopi Chand's tale is largely concerned with one or more lands called Bengal. True, the women of Madhu Nath's Bengal dress in the red and yellow wraps characteristic of Rajasthani women (rather than less garish Bengali saris) and knead and roll out wheat bread (rather than boiling rice). Nonetheless, Gopi Chand's journey to Bengal is very much a journey into fabled and remote territory. Bharthari's entire story is also located elsewhere—in Malva, a fairy-tale kingdom to Rajasthanis.

In this respect the stories of Bharthari and Gopi Chand differ strikingly from epic tales of regional hero-gods that take place in a familiar landscape. It was possible for me in 1980 to spend several weeks journeying through a storied countryside where the god Dev Narayan's life history was geophysically embodied. A slightly indented rock was reverently identified as the hoofprint of Dev Narayan's magic mare, Lila; a simple stone well was known as the divine warrior's bathing place and thus a source of healing mud and water; a row of slanted stones bowed as Devji passed by; a modest hilltop pool marked his miraculous birthsite.[7] Such imminence is not available for Bharthari and Gopi Chand. Events preceding their renunciation are not indigenous and thus not enshrined. I have, however, visited a number of sylvan shrines dedicated to Shiva in Ajmer and Bhilwara districts, near Madhu Nath's home, featuring caves where Bharthari and Gopi Chand are said to have meditated together, or spots where their tapas is memorialized by divine footprints or by a dhuni or campfire shrine with yogis' tongs.[8]

[7] For Dev Narayan as worshiped in Ghatiyali and environs see Gold 1988, 154–86; for a summary of his epic tale see Blackburn et al., eds. 1989.

[8] Such shrines to yogi gurus are of course found in many other parts of India as well.

7. Bharthari Baba's divine footprints (pagalya ) at a shrine near a well (its engine-driven pump is visible)

in a field belonging to a naga Nath community in Thanvala, Nagaur district, Rajasthan.

Nath stories and the characters who inhabit them have lives of their own that reach beyond what is available in a single telling or a single bard's knowledge. Madhu Nath's performances for me are moments in a long history. The ongoing process of transmission and diffusion through time and space brings about countless permutations. Here, I shall very briefly consider some of these permutations in order to illuminate the unique performances that are my subject. My intention is by no means to present an exhaustive inventory of extant versions but rather to highlight interesting trends in the complex history of an oral tradition.[9] I hope thereby to convey the ways that

[9] The research for this chapter led me across more than one regional and linguistic boundary. In the case of Bharthari, it also led from vernacular oral tales back to Sanskrit texts. For Sanskrit, Punjabi, and Bengali I depended on translations, or English summaries; the comparisons I offer here are necessarily circumscribed by these linguistic constraints. I found references to versions of Gopi Chand's tale in Oriya, in Marathi, and in South Indian languages (Chowdhury 1967, 186–87; Sen 1954, 73–74; Sen 1974, 68)—none of which I discuss here.

one performer's version of an oral tale emerges from multiple streams of tradition and yet has a coherence and weight of its own.

Because of their evident origins in different places, probably on different sides of North India, I shall treat the two tales of Bharthari and Gopi Chand discretely. The issue of when, where, and how they came to intersect and partially fuse—somewhere in the middle of North India—is a mystery upon which little light can be shed; that union appears to date back at least several centuries. Although in terms of the bard's repertoire, Gopi Chand is the favored performance, chronologically and conceptually Bharthari precedes it. For when Gopi Chand, advised by his mother to renounce the world, demands to know what king had ever been fool enough to become a yogi, his mother is able to cite her brother, Bharthari, as a role model. Therefore, although until now I have given precedence to Gopi Chand for several reasons (it was first in my heart and my studies, and first in the favor of Madhu Nath's audience), here I shall begin with Bharthari.

Bharthari

Tradition identifies King Bharthari as the former ruler of the real city of Ujjain, located in what is today Madhya Pradesh. Ujjain and its surroundings—an area that Rajasthani villagers even today call by its traditional name of Malva—is a frequent point of reference in local lore. Dhara Nagar, another name for Ujjain, is often the kingdom inhabited by any king who appears in Rajasthani women's worship stories. Bharthari's birth story, as told by Madhu, includes the founding of Dhara Nagar, by the grace of Nath gurus and the acts of a haughty donkey who is Bharthari's progenitor, Gandaraph Syan,[10] cursed by his father to enter a donkey womb.

Bharthari, the legendary king of Ujjain who turns Nath yogi, is generally considered to be identical with the Sanskrit poet Bhartrihari, renowned for three sets of eloquent verse on worldly life, erotic passion, and renunciation.[11] The legends surrounding the poet Bhartrihari

[10] As Nathu transcribed Madhu's pronunciation, this prince's name is sometimes Gandarap and sometimes Gandaraph , sometimes Syan and sometimes Sen . I regularize this.

[11] Whereas books about the Sanskrit poet often refer to the legendary king, the legends of Bharthari rarely refer to the Sanskrit poet—an exception being Duggal's retelling (Duggal 1979). Miller, who gives us some beautiful translations of Bhartrihari's poems, notes, "In spite of the legend, the content of the verses suggests that the author ... was not a king, but a courtier-poet in the service of a king" (Miller 1967, xvii). Bhartrihari the poet may be the same as Bhartrihari the Sanskrit grammarian, author of a famous treatise, the Vakyapadiya . Coward 1976 and Iyer 1969, 10–15, both favor this identification; Miller 1967 is more skeptical.

identify him, as Madhu identifies his Bharthari, as the elder brother of the Hindu monarch, Vikramaditya; Bharthari's decision to renounce the world brings Vikramaditya to the throne. The name of Vikram is associated with a fixed point, 58–57 B.C. , from which one major system of Hindu dating, the Vikrama era, begins. However, King Vikramaditya's status as a historical personage is also open to doubt.[12]

The tale of Bhartrihari's renunciation takes up but a few pages in the cycle of Sanskrit stories surrounding Vikramaditya. These have been translated and retold in English and are often summarized in introductions to collections of the Sanskrit poet's work.[13] The plot involves a circular chain of deception that will inevitably recall to Western readers the French farce and opera plot evoked by the title La Ronde .

A Brahman, as a reward for his intense austerities, receives the fruit of immortality from God; he presents this prize to King Bhartrihari, who gives it to his adored wife, Pingala.[14] She, however, passes it on to her paramour, and he to a prostitute who offers it once more to the king. Having extracted the truth from each link in this chain, and stunned not only by his queen's perfidy but by the generally fickle ways of the world, Bhartrihari decides then and there to pursue a more stable reality, turning the rule of his kingdom over to Vikramaditya.[15]

Madhu Nath's version of Bharthari's story does not include any

[12] For the historicity of King Vikramaditya see Edgerton 1926; Sircar 1969.

[13] See Edgerton 1926 for translations from the Sanskrit; see also Bhoothalingam 1982 who adapted a Tamil version of the Sanskrit for young readers in English. For an elaborate, embellished retelling in Hindi see Vaidya 1984, 7–24. Versions of the story are also referred to in Miller 1967; Kale 1971; Wortham 1886.

[14] As a woman's name, Pingala is rare. The RSK lists a variant, Pingala as a name of the goddess Lakshmi as well as the name of Bhartrihari's wife. Its primary meaning, however, is one of three main, subtle channels in the human body described by yogic physiology.

[15] Some elaborations on the story have Bhartrihari first exiling Vikramaditya after the debauched queen accuses him of assaulting her honor in order to cover up her real indiscretion. Then Bhartrihari must recall Vikramaditya and exonerate him before following the guru Gorakh Nath to a renouncer's life (Duggal 1979).

reference to tins circle of illicit connections. Pingala here is an impeccably true wife. Rather than woman's infidelity, the premise of Madhu Nath's tale is that even the most faithful woman is part of the illusory nature of the universe and thus not worth loving. Jackson in a note on the lore surrounding Bharthari's Cave—a famous shrine in Ujjain—and Rose in his ethnographic survey of the Northeast both relate stories similar to Madhu Nath's in which Pingala is true (Jackson 1902; Rose 1914). Gray translates a fifteenth-century Sanskrit play, the Bhartrharinirveda of Harihara, that also has a plot very similar to the Rajasthani folk telling (Gray 1904). However, to my knowledge all the popular published dramas and folk romances (kissas ) [16] about King Bharthari and Queen Pingala center on the fruit of immortality and Pingala's deceit (but she usually reforms in the end).

Although I have called attention to a dramatic dichotomy between types of Pingalas in Nath traditions, let me note that these striking differences mask an underlying symmetry. In the end, it is women—true or false, beloved or despised—whom yogis abandon. Madhu Nath's version actually seems at one moment in the arthav to consider Pingala's fanatic fidelity as yet another dangerous feminine wile. Gorakh Nath implies that by becoming sati Pingala was trying to kill her husband. And yet if we shift perspectives once again, we may view both types of Pingalas as the impetus for Bharthari's enlightenment, and thus as valued positive forces in these tales of renunciation.[17]

Bharthari and Gopi Chand's relationship—both as maternal uncle

[16] For popular folk romances based on the Vikram cycle, including brief references to Bharthari and the fruit of immortality, and an insightful discussion of "women's wiles" in this genre, see Pritchett 1985, 56–78.

[17] With a script that explains Bharthari's infatuation and Pingala's perfidy through predestination, one version of the tale actually makes such a collapse nicely logical. Dehlavi's Hindi play Bharthari Pingala frames the fruit-of-immortality circle with a glimpse into Bharthari's previous birth as one of Gorakh Nath's disciples, Bharat Nath. While on an errand for his guru, Bharat Nath is distracted by a beautiful fairy and sports with her in the woods. The fairy is punished for misbehaving with a yogi by Indra, the king of the gods, who forces her to take a human birth. Bharat Nath is given the same sentence by his guru. Indra tells the fairy that she will deceive her husband and cause him to renounce the world, consequently suffering the heavy sorrow of widowhood in her youth (Dehlavi n.d., 32). To mitigate Bharat Nath's misery, Gorakh promises his errant disciple that the same beautiful female who caused his downfall will bring about his reunion with the guru (26). In this frame Pingala's infidelity represents not lack of character but a cosmic plan. Bhoju reports hearing a very similar version from a Brahman schoolteacher who saw it performed in Alwar; that tale tidily made Pingala's lover an incarnation of Guru Gorakh Nath.

and nephew, and as two Naths with immortal bodies—is mentioned in several versions other than Madhu Nath's (Dehlavi n.d.; Dikshit n.d., 264). In Rajasthani folklore not contained within the epic tales themselves, Bharthari and Gopi Chand are paired as immortal companions still wandering the earth. Thus they appear as the authors of hymns (bhajans ) to the formless lord (Gold 1988, 1O9) and are recalled in proverbs: "As long as sky and earth shall be / Live Gopi Chand and Bharthari" (Jab tak akash dharati, tab tak Gopi Chand Bharthari ). Most of the longer versions of Bharthari's tale make some reference to his gaining an "immortal body" (amar kaya ), but none is particularly illuminating about the nature of this immortality. Madhu Nath never refers to immortality in telling the tale of Bharthari, but when Gopi Chand receives the blessing (or curse) of immortality from Jalindar Nath, in part 4 of his separate tale, Bharthari is with him and shares in the fruit.

Distinctive to Madhu's telling is a general concern for mundane detail: many descriptions of actions and relationships, well understood or easily imagined in village thought, that do not advance the story line but rather situate it in familiar experience. These include a gathering of village elders in time of crisis; the technology of potters; the negotiations of patrons and clients; the mutuality and interdependence of subjects and rulers. Such familiar scenes or situations may, moreover, be suddenly spiced with magical occurrences or divine intervention: donkeys talk to village elders, a guru's play spoils the carefully crafted pots; messengers come from heaven to straighten out the king and save his subjects. It would seem that Madhu and his teachers, in adapting a traditional tale for village patrons, elaborate both the familiar and the magical to strike a captivating blend. And yet, as we will see, although Gopi Chand's story certainly shares some stylistic and thematic qualities with Bharthari's, it follows a different recipe.

Gopi Chand

In Madhu's version as well as all others except those originating in Bengal, Gopi Chand is described as the king of"Gaur" Bengal. Gaur was an ancient Bengali kingdom that fell to Muslim invaders in the thirteenth century (Sarkar 1948, 8). Although there is no evidence pointing to an association of a historical Gopi Chand with the kingdom of Gaur, attempts have been made to link Gopi Chand with various

Bengali monarchs of the Pala or Chandra dynasties (Grierson 1878; Majumdar 1940); however, too many conflicting details preclude any certain confirmation of these indentifications (Chowdhury 1967, 186–87; Sen 1954).

Versions of Gopi Chand do not divide neatly into two types, as versions of Bharthari do according to Pingala's good or bad character. However, a number of motifs in Bengali versions consistently contrast with those recorded or written down in western India. [18] For example, Gopi Chand's sister is a significant figure in Madhu Nath's tale as well as in other tales from western India but is never mentioned in Bengali versions. As the stories are told in Punjab, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh, Gopi Chand must go east to Bengal to meet his sister. She is thus married into a Bengal that is alien to the Bengal that Gopi Chand rules, a doubling of distance and foreignness.

I might speculate that the journey to a sister who inevitably dies of grief, to be revived by Jalindar's magic, accrues to the non-Bengali versions in order to lend a sense of completion or closure to the king's renunciation. In two Bengali versions, Gopi Chand parts with difficulty from his wives but eventually goes back to them; in the western Indian traditions he leaves the world and women for good, after parting from his sister. Attachment to the sister is, as Madhu's Manavati Mata firmly instructs her son at one point, a far more serious matter than any bond to wives.

Like the visit to the sister, the motif of Gopi Chand burying his guru in a deep well and covering him up with horse manure occurs in all but the Bengali versions. Moreover, this episode is almost always linked, as it is in Madhu's tale, with the subplot of Gorakh Nath's journey to Bengal to rescue his guru Machhindar from magicianqueens. That is, the two gurus are ignominiously trapped in two different ways, and their respective disciples compete as to who will rescue his first. [19]

[18] I draw on Grierson 1878 and Sircar n.d. for translations from Bengali; Temple 1884 translates a Punjabi oral drama; Dikshit n.d. and Yogishvar n.d. respectively provide Hindi prose and drama versions.

[19] In all versions but Madhu Nath's that include the guru-in-the-well motif, the deliverance of both gurus (Machhindar from Bengal and Jalindar from the well) occurs before, not after, Gopi Chand's initiation. Thus, Jalindar's magical power to be up and about and active in Gopi Chand's tale, despite being down a well and buried under horse dung (which we must accept in order to follow Madhu's plot line), is unnecessary in these more "logically" structured versions. Perhaps somewhere en route to Rajasthan the plot sequence was rearranged.

I initially thought that the lengthy episode concerning those troublesome females, the seven low-caste lady magicians of Bengal, was unique to the Rajasthani Gopi Chand. As some of these characters appear in other Rajasthani folk traditions, this surmise seemed plausible.[20] However, although no other versions give anything near the weight and the detail that the Rajasthani does to Gopi Chand's female adversaries or place them as obstacles between the king and his sister, Bengali and Hindi texts do have Gopi Chand's progress obstructed by one or more lowborn, low-living, magic-wielding females. I have argued elsewhere that the Rajasthani version, which allows both king and audience to develop so much sympathy for Gopi Chand's kinswomen, especially needs the lady magicians to make parting from virtuous females less cruel. The Bengali magicians are women the Rajasthani village audience loves to hate (Gold 1991).

One element that all six versions notably have in common is the dynamic instigating role played by Gopi Chand's mother. In all versions Gopi Chand's mother is a religious adept—although her role may range from immortal, wonder-working magician to dedicated devotee. In all versions it is she who makes the fateful decision that her son should become a yogi—an idea that would obviously never have occurred to Gopi Chand of his own accord.[21] Thus, Gopi Chand is propelled toward renunciation, just as is Bharthari, by a woman.

In the Bengali versions of the tale—which we may accept as probably closer to an "original" version insofar as they are produced in the hero's native region—Manavati is a powerful yogini who has learned the secret of immortality. This is in accord with Bengal's reputation in the rest of India as a place of powerful females.[22] Never-

[20] See Bhanavat 1968 for an episode concerning Gangali Telin, one of the lady magicians who torments Gopi Chand, in Rajasthani lore on Kala—Gora Bhairu or "Black Bhairu and Fair Bhairu."

[21] An exception I encountered as this volume goes to press is a new report on fieldwork among Naths in Bhojpur (eastern Uttar Pradesh); C. Champion describes a version of Gopi Chand, "completely different from the Bengali" in which his mother, "confronting her son's decision to become a renouncer tries only to interfere by invoking all the arguments in her possession" (Champion 1989, 66; my translation).

[22] For a discussion of legends about an Eastern kingdom of women see McLeod 1968, 110–12. Even travel literature of this century may capitalize on such legends and their possible anthropological realization. In one such account Bertrand refers to Bengalis' fear of "sorceresses having the power to change men into animals" (Bertrand 1958, 173); see also Dvivedi n.d., 53–54. In a comprehensive survey of women in Bengali literature, Rowlands 1930 discusses Gopi Chand's mother and wives.

theless, even in Bengal it is not so easy for a woman to be a guru. Sircar's unpublished translation from the Bengali contains a vivid rendition of this plight of the divinely powerful yet domestically powerless woman. She describes to her son how her husband, Gopi Chand's father, preferred death to having his wife as a guru: "You are but the wife of my house, / but I am the master of that house. / If I accept wisdom from a housewife / How can I call her guru and take the dust off her feet?" (Sircar n.d., 13).[23]

Chief among the distinctive aspects of Madhu Nath's account are a critical plot feature and an attendant emotional timbre. Madhu's is the only text that explains Gopi Chand's birth as a loan to his mother (although others do ascribe it to his mother's devotions or asceticisms).[24] Although all the versions have Gopi Chand initially resist the idea of renouncing the world, Madhu's is the only one in which Gopi Chand perpetually laments and sorrows, calling on his guru like a child at every difficult moment. These two factors are in constant interplay in Madhu's text. By portraying Gopi Chand as doomed to yogahood but attached to the world, by having his feelings oppose his destiny, Madhu's tale creates a space for resistance and generates the human drama (or melodrama) that made me wish to translate this tale as a counterpoint to prevailing images of resolute renouncers.

In other versions it is women who display most of the emotion; Gopi Chand passes through their pleas and reproaches with a certain dignified detachment (much as Madhu's Bharthari hears out and denies Pingala). But Madhu Nath elaborates on the king's inner turmoil, not only by returning again and again to the rainstorm of tears in his eyes, but also by providing trains of consciousness (veg ) or reveries when Gopi Chand expresses his regret, despair, and simple shame.

Like his telling of Bharthari's story, Madhu's Gopi Chand tale incorporates some familiar details of daily rural life: the ways that barren women seek divine remedies; the washerwoman's rounds to

[23] See O'Flaherty 1984, 16O, 280–81, for a case from Sanskrit mythology rather than Nath folklore in which a wise wife must resort to extreme subterfuge in order to act as her husband's guru.

[24] David White (personal communication 1990) pointed out to me that the idea of a human life as a loan is a very ancient one in Hindu thought. See Malamoud for a comprehensive discussion of "a theory of debt as constitutive of human nature" in Sanskrit texts (Malamoud 1989, 115–36).

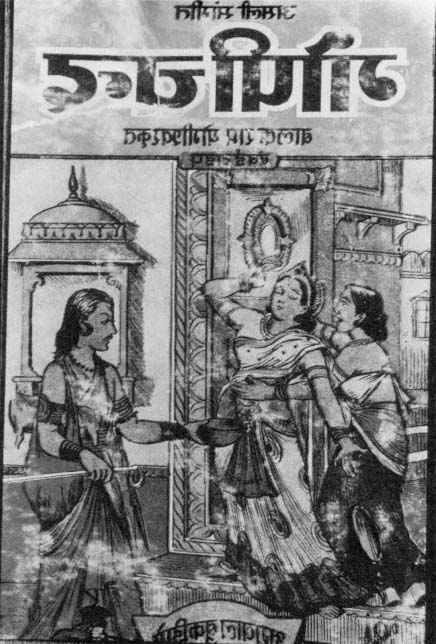

8. Gopi Chand's queen faints as her husband in yogi's garb begs for alms; faded cover

illustration for Balakram Yogishvar's published Hindi play of Gopi Chand .

collect laundry; the companionable filling of water pots by groups of women. But, while these mundane details can seem to dominate his Bharthari performance, generating more interest than do the chief characters and their problems, in Gopi Chand's story the setting is always subordinated to character and interpersonal dynamics.[25]

In Madhu's version of Bharthari, magical moments are embedded in a realistic tapestry of rural life—a life inhabited by largely twodimensional characters. In his Gopi Chand, events in the world float on the surface of deeply reverberating internal spaces and highly charged interpersonal channels. These inner worlds, moreover, are not bounded. That the same bard can present two tales of renouncerkings so differently suggests that the tales themselves, despite being part of the common lore of the Nine Naths, have retained distinctive features of their disparate origins.