In the late medieval era it was not possible to think of a community without also attending to the place of leadership within it. According to the common understanding, every social organism was a body politic in which head and members worked together for the common good. A community lacking a head was, like the human body on which it was modeled, either dead or an enormity. This theme was especially important in cities, since what held them together was their corporate existence, which in turn depended on the ability of their governors to act for the whole polity. Their governing powers required constant justification and continuous reinforcement. Not surprisingly, celebrations of authority became one of the great subjects of urban culture in the period. Embedded in them was a particular view of authority according to which the right to make decisions for the community depended on public recognition of the individual’s worthiness for the task. The activities of St. Katherine’s players in uniting the members of the city’s most important craft with the officials of the Corporation was only one among the many ceremonial means addressing this issue.

In the fifteenth century, Bristol’s government, established by Edward III’s charter of 1373, was a self-perpetuating, closed institution of forty-two citizens. Its members were chosen by co-optation, and its chief officers, the mayor and a single sheriff, were elected exclusively from among its own membership. As described by Ricart, election proceedings began on St. Giles Day, 1 September, when the mayor’s four sergeants officially warned the membership of the Common Council of the impending election. The election itself was held on 15 September, and failure to appear subjected each absent councillor to a fine of £10, very steep for the period. Candidates were nominated as well as chosen on 15 September, and each election was conceived to be a spontaneous judgment by the councillors about who was best suited to serve the city. The voting proper began with the current mayor “first by his reason” naming and giving “his voice to some whorshipfull man of the seide hows,” that is, nominating and voting in the same motion. “[A]fter hym the Shiref, and so all the house perusid in the same, euery man to gyve his voice as shall please him.” In theory, it was possible for each council member to nominate a new candidate, including himself, when his time came to give his voice. The victor was “hym that hathe moste voices.” In fact, contests appear to have been exceedingly rare. But participation by the entire membership in this way helped to bind them in obedience to the new regime, since the councillors were much less free to criticize or oppose the new officers at a later date if they had played a part in selecting them. The vote of every member was to be based on the principles of spontaneity and openness. An election was the free choice of the assembled civic leadership made according to the community’s highest ideals. Reason and good conscience were to be used to find the best person to serve the commonwealth for the coming year.[17]

Election to the mayoralty was a great honor in the city. In recognizing the worthiness of the man for this office of trust, it enhanced his social importance both by the deference that his fellow townsmen would now show him and by the opportunity his office gave to display his wealth to the city. The office was also a burden, requiring time away from personal business and the outlay of large sums to support the ceremonial requirements of officeholding. The mayor had little independent political power, however, since his freedom of action was restrained by the legal forms he was obliged to follow and by the council, which acted as a check upon his formulation of policy. Nevertheless, because the office brought enhanced status it carried political weight: status, especially when given official recognition, rewarded the recipient with greater influence in local affairs and brought his fellow townsmen to him for wise counsel.[18]

In the public presentation of the new mayor, all these considerations played a role. The process began at once. Having been in “due form electid,” the successful candidate was to “rise fro[m] the place he sat in, and come sytt a dextris by the olde maires side,” there to participate in subsequent deliberations. Once these “communications” had been completed, attention was turned to making the new mayor known to the town. With the adjournment of the election meeting, he was worshipfully accompanyed, with “. . . certein of the seid hous, home to his place,” in effect publicly announcing the election to all who observed this mayoral party pass through the streets.[19]

The official date for the new mayor’s installation into office was Michaelmas, 29 September, fully two weeks after the election. In the interval, Ricart tells us, “the seide persone so electid maire shalle haue his leysour to make his purveyaunce of his worshipfull householde, and the honourable apparailling of his mansion, in as plesaunt and goodly wise as kan be devised.” When his house was readied for the festivities to come, the new mayor was to come to the Guildhall in a full-scale procession in which he took his proper place as the head of the government, “accompanyd with the Shiref and all his brethern of the Counseill, to feche him at his hows and bring him to the seide hall, in as solempne and honourable wise as he can devise to do his oune worshippe.” Since the mayor was the head not only of the government but of the community, it was proper for him to enter office “to the honour, laude, and preysyng” of all Bristol, whose inhabitants perforce witnessed the procession as it made its way through the streets.[20]

Because of the preeminence of the mayor in the civic hierarchy, the ceremony at his inauguration was extremely rich in meaning and detail. His formal installation into the seat of authority was accomplished only after he had been reminded of his responsibilities to the borough community and sworn to his duties. Before administering the oath, the outgoing mayor made a speech to his brethren and the others assembled that stressed the commonweal of the city and the maintenance of unity among the citizens. According to Ricart, he apologized to his fellow townsmen for any offense he might have given and offered to make amends for his errors from his own goods or to “ask theym forgevenes in as herty wyse” as he could, “trusting verilly in God they shal haue no grete causes of ferther complaynts.” If he could not heal all the wounds that his government might have caused, the mayor continued, the “worshipfulle man” chosen to be the new mayor “of his grete wisedome, by goddes grace, shal refourme and amende alle such thinges as I of my sympileness haue not duely ne formably executed or fulfilled.” Finally, the outgoing mayor thanked his fellow citizens for their “godeness” according to their “due merits” in showing “trewe obedience to kepe the king our alther liege lorde is lawes, and my commaundment in his name, at all tymes,” and he prayed that God would reward them with “moche joy, prosperitie and peas, as evir had comens and true Cristen people.”[21]

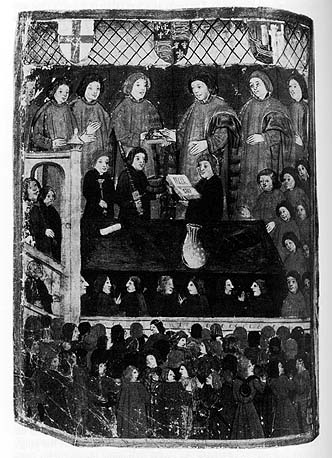

After the speaking of these significant words came the swearing-in of the new mayor (Figure 5). The oath, as it was taken in Ricart’s time and with some small changes at least to the end of the sixteenth century, was preoccupied with the formal and specific tasks undertaken by the mayor that had been laid out in the city’s charters.[22] Ricart shows the incoming mayor swearing on a book, almost certainly the Bible, held by the outgoing mayor; the common councillors sit or stand around the council table. A number of citizens appear at the periphery. The town clerk reads the oath, the swordbearer holds the cap and sword of justice, and an assistant holds the seal mentioned by Ricart. On the council table we see a large pouch (probably containing monies to be received into the new mayor’s care), a scroll, and an account book. The room itself is decorated with the royal arms in the center, the Cross of St. George to the left, and the arms of the town of Bristol to the right. Standing at the “high deise” of the Guildhall, before his fellow common councillors and members of the “Comyns,” the inauguree swore allegiance to the monarch to “kepe and meyntene the peas of the same toune with all my power.” Under this authority he then promised to “reproue and chastice the misrewlers and mysdoers in the forsaid toune,” to maintain the “fraunchises and free custumes whiche beth gode,” to put away “all euell custumes and wronges,” to “defende, the Wydowes and Orphans,” and to “kepe, and meyntene all laudable ordinaunces.” Most important, he also swore “trewely, and with right,” to

trete the people of my bailly, and do every man right, as well to the poer as to the riche, in that that longeth to me to do. And nouther for ghifte nor for loue, affeccion, promesse, nor for hate, I shall do no man wronge, nor destourbe no mannes right.[23]

In these clauses the mayor is viewed largely in his capacity as a judge. The underlying theme, even where the enforcement of municipal ordinances is concerned, is one of judiciousness and evenhandedness.[24] By the formula of the oath, the mayor’s role within the city rests almost entirely on his position as the king’s vicegerent in the city. This same emphasis is apparent at the conclusion of the oath. After kissing the book held for him by the outgoing mayor, the new mayor received from the hands of his predecessor the essential symbols of his office: the king’s sword and the cap of justice, the casket containing the seal of his office as escheator, the seal of the Statute of the Staple, and the seal of the Statute Merchant, all signifying the judicial authority the mayor derived from the Crown.

The Swearing of the New Mayor at Michaelmass in the Late Fifteenth Century. (Robert Ricart, The Maire of Bristowe Is Kalendar, Bristol Record Office, MS 04270 (1), f. 152. By permission of the City of Bristol Record Office.)

[Full Size]

When taken together with the outgoing mayor’s speech, however, the inauguration conveys a more complex picture of the mayor’s role. Although his authority derived from a royal grant, its base was local. He was the king’s lieutenant in the city, but the borough’s servant. As head of the community he could act as a buffer between the Crown and the city, protecting it from corrosive outside interference and permitting it the maximum autonomy by carrying out the king’s business and maintaining peace in his name. The mayor’s duty was, with the aid of the Holy Trinity, to keep the city “in prosperouse peas and felicite” and to preserve its internal solidarity by maintaining the social fabric against all damage, especially that caused by misgovernment.[25]

Along with the formal oath-taking, which renewed the bonds of authority, there were also informal proceedings which were intended to promote the internal solidarity of the civic body. The first of these festive events occurred immediately after the mayor had taken his oath. Once the symbols of office had been handed over to him, he immediately changed places with his predecessor and “all the whole company” brought “home the new Maire to his place, with trompetts and clareners, in as joyful, honourable, and solempne wise as can be devised…there to leve the new Maire, and then to bring home the olde Maire.”[26] These honorific processions were followed by communal dinners, the majority of the council dining with the new mayor at his house and a smaller number, including all the officers, dining with the outgoing mayor. After they had eaten, “all the hole Counseille” assembled at the High Crosse, in the town center,

and from thens the new maire and the olde maire, with alle the hole company, to walke honourably to Seint Mighels churche, and there to offre. And then to retorne to the new Maires hous, there to take cakebrede and wyne. And then, evey man taking his leeve of the Maire, and to retray home to their evensong.[27]

This ceremony repeated in a symbolic way the transfer of authority from the outgoing to the incoming mayor. First the council was divided to honor, some one man, some the other, by being his guests. The two mayors then jointly led a slow and stately procession uphill to St. Michael’s Church. The mood seems to have been one of reluctant farewell to the outgoing mayor. But after the offering at St. Michael’s the tone would have changed. The return to the town center, downhill, undoubtedly conveyed a lively spirit of energetic and joyful new beginning. To conclude the celebration, all were united at the new mayor’s house, where they sealed the transition of power by sharing his cheerful hospitality.