II.

The Intellectual as Good Citizen

We should not imagine that we are able to see such a head in the same way Plato's contemporaries saw it.

—Hans-Georg Gadamer

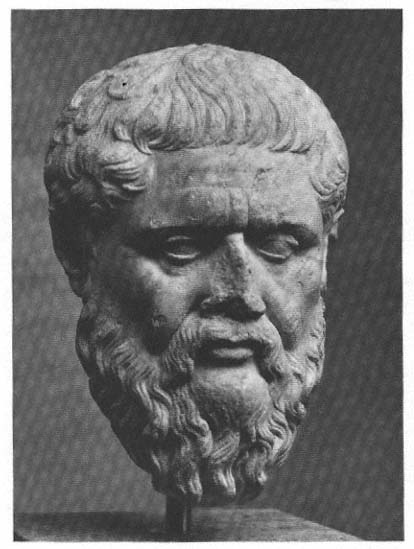

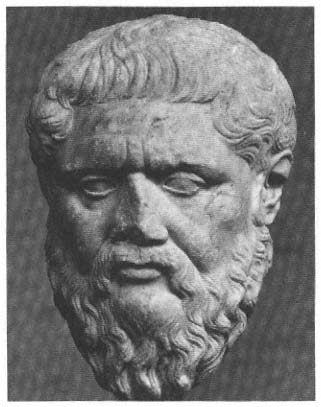

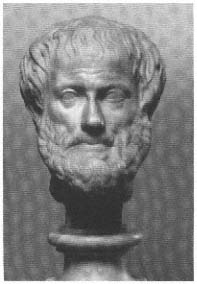

Recently the Glyptothek in Munich acquired a particularly fine Roman copy of the portrait of Plato (fig. 24). Among those who tried to penetrate the stern countenance was the philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer, who detected "Attic wit . . . , something of extreme skepticism, abstracted and distant, almost mocking," especially in the mouth and eyes. At the same time, the distinguished interpreter shrewdly called attention to Plato's dialogues, "the successor to Attic comedy," to qualify the provisional nature of his own reaction.[1]

Archaeologists have also attempted, with a similarly direct approach, to find in Plato's face a reflection of his character, fortunes, or intellect. So, for example, Wolfgang Helbig saw an "ill-tempered, even malevolent quality," while Ernst Pfuhl found an "inner tension joined with the painful resignation that comes of bitter disappointment." Helga von Heintze discovered how "the innermost thoughts and experiences reveal themselves in the earnest, knowing, and concentrated gaze and the firmly closed mouth." Clearly, viewers find in this face what they look for, based on their personal preconceptions of the subject, especially in this case, where the different renderings of the expression in the various preserved copies seem at different times to favor one or another interpretation.[2]

But even archaeologists had to work their way gradually into the Plato portrait before they could arrive at such profound interpretations. "The head occasioned mainly great disappointment when it first became known, for it did not correspond at all to the way people imagined Plato. . . . They sought in vain a characterization of the 'divine Plato,'" or they regretted that the artist "rendered little or nothing of

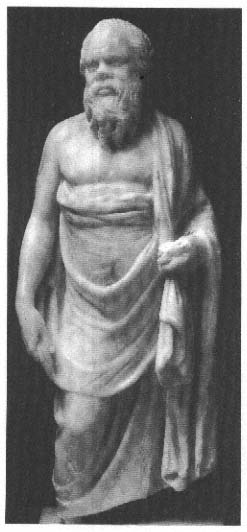

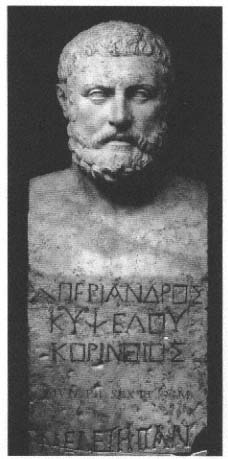

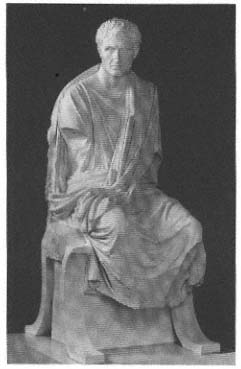

Fig. 24

Plato. Copy of the time of the emperor Tiberius of a portrait statue of

the mid-fourth century B.C. Munich, Glyptothek.

the subject's true nature."[3] This lack of expressiveness and individual characterization in Late Classical portraits must have been felt already in the Hellenistic period, when the portrait of Plato was reshaped into a more communicative one, in the style of contemporary Stoic notions of the physiognomy of the thinker (cf. pp. 92ff.).[4]

The Romans had already tried this kind of psychological reading of the imagines illustrium of the Greeks, which were exhibited by the thousands in their homes, gardens, and libraries, usually as herms or busts with the name inscribed. Just like the modern viewer, they wanted to know "qualis fuit aliquis," as Pliny the Elder put it (HN 35.10f.), in order to use the portraits in their own intellectual retreats. Since they no longer understood the body language of Greek statuary, they usually had copies made only of the heads, assuming, quite naturally, that these were realistic, individual likenesses in the same sense as their own portrait sculpture.

Even modern viewers who are aware that the Greeks always made full-length portrait statues nevertheless find themselves confronted by disembodied heads and remain, like the Romans, nolens volens, fixated on them. In so doing, we perhaps look too closely and ask too much of a face that was intended to be seen in a very different context. Nor are we any better able than the Romans to free ourselves of deeply ingrained ways of seeing, in our case especially shaped by our experience of photographic likenesses. As a result, we search for any indication of individual physiognomy that we can associate with the character and work of the subject. Even when we know that this was not the original intention of a Classical portrait, we can hardly escape our own conditioning.

We must admit, then, that we have no direct access to an understanding of Plato's physiognomy. We can only try, by indirect means, to create the theoretical framework for such an understanding. What is of interest for our inquiry is not the often-asked but unanswerable question of how true to life the portrait is, but rather how specific intellectual traits are indicated. In other words, does this portrait characterize Plato in any way whatsoever as a philosopher, or simply as a mature Athenian citizen conforming to the basic expectations of the polis?

It is my contention that in fourth-century Athens there was no such thing as a portrait of an intellectual as such, and indeed that in the social climate of the democratic polis there could not have been. In order to demonstrate this, I should first like to deal with some retrospective portraits of famous fifth-century Athenians from the period of the Plato portrait. These are statues for which we can reconstruct the context in which they were originally displayed and we can gain a rough idea of their original content. Then I shall return to the question of Plato's much-interpreted expression. Finally, at the end of this chapter, I shall consider two portraits that demonstrate how the strict standards of behavior of the Classical polis broke down in the Early Hellenistic period, giving rise to new options, including the representation of intellectual qualities.

Statues Honoring the Great Tragedians

About the year 330 B.C. , Lycurgus, the leading politician in Athens, who was also in charge of state finances, proposed in the Assembly a decree for the erection of honorific bronze statues of the three great Classical tragedians, Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, who had been active roughly a century before. The statues were to be set up in the Theatre of Dionysus, where their plays had been performed and where, in addition, the Assembly itself met (ps.-Plut. X orat., Lyc. 10 = Mor. 841F; Paus. 1.21.1–2). An authentic and definitive text of their works was also to be established and used as the basis for all future productions. This remarkable project was part of an ambitious program of patriotic national renewal.[5]

Sophocles: The Political Active Citizen

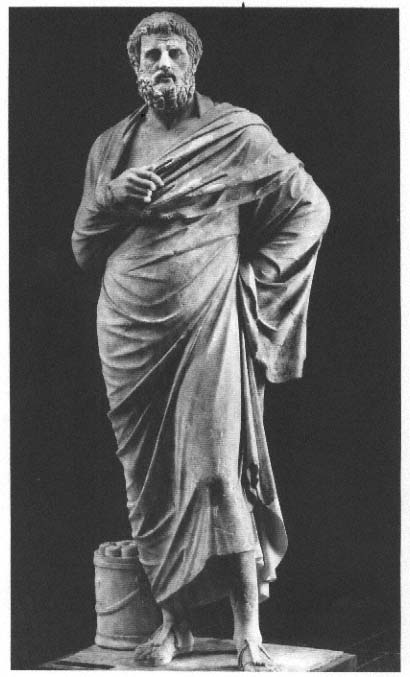

The statue of Sophocles belonging to the dedication seems to be faithfully rendered in an almost fully preserved copy of the Augustan period (fig. 25).[6] Sophocles stands in an artful pose that appears both graceful and effortless. The mantle carefully draped about his body enfolds both arms tightly. The right arm rests in a kind of loop, while the left, under

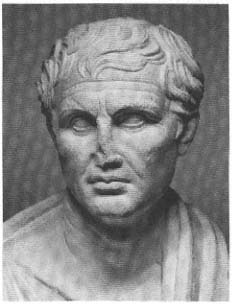

Fig. 25

Sophocles. Roman copy of a statue ca. 330 B.C. Rome, Vatican Museums.

the garment, is propped on the hip. The drapery allows even the legs little room for movement. Yet at the same time that he is so heavily wrapped, the position of the one advanced leg and the one arm propped up conveys a sense of energy and a commanding presence. The head is turned to the side and slightly raised, the mouth open. We have the impression that the poet is making a certain kind of public appearance. Among the Attic grave stelai, which repeatedly display the narrow range of acceptable poses and drapery styles that reflect standards of citizen behavior in this period, there is no male figure who matches this combination of being both heavily wrapped and yet making such an elegant and self-assured appearance. There is, however, a statue of the orator Aeschines, only slightly later in date, in a similar pose (fig. 26). This raises the possibility that Sophocles, too, is depicted as a public speaker.[7]

The model orator was expected to demonstrate extreme modesty and self-control in his appearances before the Assembly, and particularly to avoid any kind of demonstrative gestures. Thus this particular pose, with very limited mobility and both arms completely immobilized, along with the self-conscious sense of "making an appearance," would be particularly appropriate for an orator. Alan Shapiro has recently called attention to a red-figure neck amphora by the Harrow Painter, dated ca. 480 B.C. , on which a man is depicted in the same pose as Sophocles, standing on a podium, in front of him a listener leaning on his staff in the typical citizen stance (fig. 27). Most likely we have here indeed a representation of an orator.[8]

But why depict a tragic poet of the previous century in the guise of an orator? The issue of what constituted the proper bearing and conduct for public speakers, the correct attitude toward the state and its citizen virtues, was the subject of a lively debate in Athens in the years just before Lycurgus put up his dedication. If we may believe Aeschines, most politicians of his generation no longer observed the traditional rules of conduct but gesticulated wildly for dramatic effect, just as the demagogue Kleon had been accused of doing in the late fifth century. Aeschines' great rival Demosthenes seems to be one of those who at least sympathized with these supposedly undisciplined speakers.[9]

Fig. 26

Statue of the orator Aeschines. Early Augustan

copy of a statue ca. 320 B.C. Naples, Museo Nazionale.

In his plea for speakers to display a calm and self-controlled appearance, Aeschines invokes the example of earlier generations and, in particular, cites a rule stating that the speaker must keep his right arm still and wrapped in his cloak through the duration of his speech. Aeschines would naturally have equated this proper stance with ethical and moral

Fig. 27

An orator speaks from the podium. Attic

neck amphora, ca. 480 B.C. Paris, Louvre.

correctness (sophrosyne ). In this connection he refers explicitly to a statue of the lawgiver Solon in the Agora of Salamis:

And the speakers of old, men like Pericles, Themistocles, and Aristides, were so controlled [sophrones ] that in those days it was considered a moral failing to move the arm freely, as is common nowadays, and for this reason speakers did their best to avoid it. And I can give you definite proof of this. I'm sure you have all been across to Salamis and seen the statue of Solon there. You can then verify for yourselves that, in this statue in the Agora of Salamis, Solon keeps his arm hidden beneath his mantle. This statue is not just a memorial, but is an exact rendering of the pose in which Solon actually appeared before the Athenian Assembly.

(In Tim. 25)

Aeschines' opponent, Demosthenes, quickly responded to this, also in the Assembly, and made direct reference to the supposedly authentic statue of Solon:

People who live in Salamis tell me that this statue is not even fifty years old. But since the time of Solon about 240 years have passed, so that not

even the grandfather of the artist who invented the statue's pose could have lived when Solon did. He [Aeschines] illustrated his own remarks by appearing in this pose before the jury. But it would have been much better for the city if he had also copied Solon's attitude. But he didn't do this, just the opposite.

(De falsa leg. 251)

The controversy over the statue of Solon provides us not only proof of the importance of the pose with one arm wrapped up in the mantle. It also represents rare and valuable testimony to the function and popular understanding of public honorific monuments in the Classical polis. That is, in certain situations and in particular locations, a statue such as this one could become a model and a topic of discussion and could take on a significance far beyond the occasion of its erection. The statue was thus incorporated into the functioning of society in a manner altogether different from what we would expect from our own experience.

Aeschines himself, of course, appeared exactly in the pose of the speakers of old. And in the view of both his supporters and his detractors, he did so in a strikingly elegant and admirable manner. The statue in his honor, referred to earlier, does indeed show him in this very pose.[10] His statue evidently led Demosthenes to make the ironic comment that in his speeches Aeschines stood like a handsome statue (kalos andrias ) before the Assembly, a pose for which his earlier career as an actor had prepared him well.[11] But this is apparently just what Aeschines intended, to stand as still as a statue.

The debate over how one should properly appear before the Assembly was not, of course, simply a matter of aesthetics. In Classical Athens, the appearance and behavior in public of all citizens was governed by strict rules. These applied to how one should correctly walk, stand, or sit, as well as to proper draping of one's garment, position and movement of arms and head, styles of hair and beard, eye movements, and the volume and modulation of the voice: in short, every element of an individual's behavior and presentation, in accordance with his sex, age, and place in society. It is difficult for us to imagine this degree of regimentation. The necessity of making sure their appearance and

behavior were always correct must have tyrannized people and taken up a good deal of their time. Almost every time reference is made to these rules, they are linked to emphatic moral judgments, whether positive or negative. They are part of a value system that could be defined in terms of such concepts as order, measure, modesty, balance, self-control, circumspection, adherence to regulations, and the like. The meaning of this is clear: the physical appearance of the citizenry should reflect the order of society and the moral perfection of the individual in accord with the traditions of kalokagathia . Through constant admonition to conform to these standards of behavior from childhood on, they became to a great extent internalized. No one who wanted to belong to the right circles could afford to throw his mantle carelessly over his shoulders, to walk too fast or talk too loud, to hold his head at the wrong angle. It is no wonder that the individuals depicted on gravestones, at least to the modern viewer, look so stereotyped and monotonous.

The statues of Sophocles and Aeschines are therefore meant to represent not only the perfect public speaker, but also the good citizen who proves himself particularly engaged politically by means of his role as a speaker. The motif of one arm wrapped in the cloak had been a topos of the Athenian citizen since the fifth century and would continue into late antiquity, both in art and in life, as a visual symbol of sophrosyne, here meaning something like respectability. Indeed, rigid standards of behavior as an expression of generalized but rather vague moral values are a well-known feature of other societies. In fourth-century Athens, however, we have the impression in other respects as well that the aesthetic regimentation and stylization of everyday life increased as the values expressed in the visual imagery became increasingly problematic.

A glance at earlier occurrences of the Sophocles motif will help clarify its significance when applied to the public speaker. In vase painting of the fifth century, it is primarily adolescent boys who wear their mantle in the style of Sophocles, with both arms wrapped up. They appear in two contexts in which it was essential for them to display their modesty (aidos ): standing before a teacher and in scenes of erotic courtship.[12] The average citizen, by contrast, is usually de-

picted in a more relaxed pose. In the fourth century we occasionally find men with both arms concealed like Sophocles, usually as pious worshippers on votive reliefs.[13] Here again the point is to display modesty and awe, in this case before the divinity. The revival and spread of this long-antiquated gesture of extreme self-control for public speakers in the fourth century also carry a deliberate message for the demos and for the democratic system then in a state of crisis. It was precisely this concern for the democracy that was the focus of Lycurgus' political program.

But let us return to the statue of Sophocles. It presents the famous playwright not at all in that guise, but rather as a model of the politically concerned citizen. The fillet in his hair probably refers to his priestly office.[14] It is of no consequence whether the historical Sophocles did in fact take a particularly active role in politics or not. One of his contemporaries, Ion of Chios, remarks of him drily: "As for politics, Sophocles was not very skilled [sophos ], nor was he especially interested or engaged [rhekterios ], like most Athenians of the aristocracy" (Ath. 13.604D). The poet did, however, serve as general in the year 441/0.[15]

In any event, nothing about the statue of Sophocles alludes to his profession as a poet, neither the body nor the head (cf. fig. 40), which, with its well-groomed hair and carefully trimmed beard, perfectly matches the conventional portrait of the mature Athenian citizen on grave stelai and, like the portrait of Plato, has understandably often been perceived as lacking in expression. But this was just what those who commissioned the statue intended: to show Sophocles as a citizen who was exemplary in every way, including in his political activity, no more and no less than an equal among his fellow citizens, a man whom Lycurgus and his friends would wish to count as their contemporary.[16]

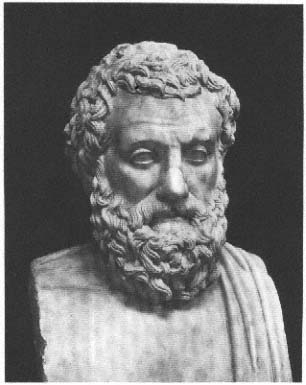

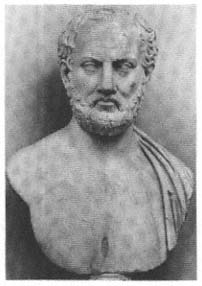

Aeschylus: The Face of the Athenian Everyman

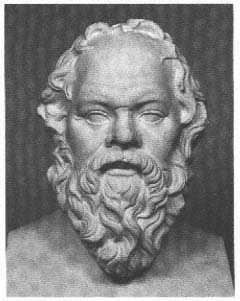

Identifying the portraits of the other two tragedians in Lycurgus' dedication is unfortunately more problematical, the evidence more fragmentary. A head that has convincingly been associated with the lost

Fig. 28

Portrait herm of the playwright Aeschylus. Augustan

copy of a statue ca. 330 B.C. Naples, Museo Nazionale.

statue of Aeschylus portrays a man somewhat younger than Sophocles (fig. 28).[17] The subtly indicated lines in the brow are a feature that he shares, as we shall see, with many images of contemporary Athenian citizens. He too is a conventional type, as is evident from a comparison with the head of an Athenian named Alexos, from a wealthy family tomb monument of the same period (fig. 29).[18] As with Sophocles, there is no hint of intellectual activity in the expression, nor anything of Aeschylus' own character, for example, his severity (Aristophanes

Fig. 29

Head of Alexos from an Attic grave stele

ca. 330 B.C. Athens, National Museum.

Frogs 804, 830ff., 859). Rather than as poet, he too seems to have been depicted simply as a good Athenian citizen.[19] As for the body type, which is thus far not preserved, we can suppose, based on his age (in his middle years), on the billowing mantle on the herm copy in Naples, and on the typology of such figures on the gravestones, that he must have been standing erect.

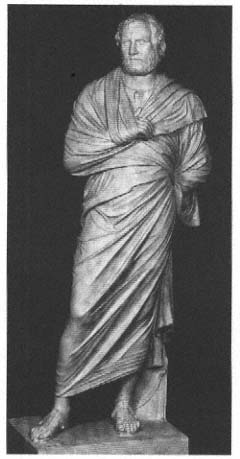

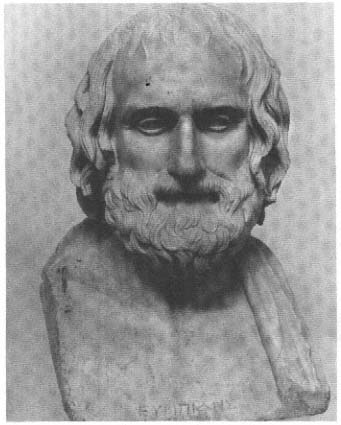

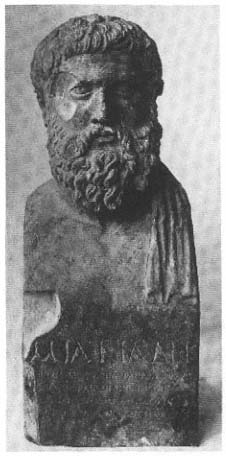

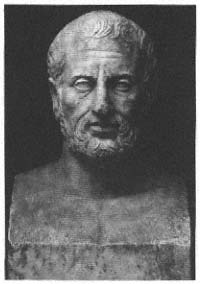

Euripides: The Wise Old Man

For the portrait of Euripides in Lycurgus' dedication the only candidate, on stylistic grounds, is, in my view, the inscribed copy known as the Farnese type (fig. 30).[20] It shows the poet as an elderly man with bald pate, a fringe of long hair, and subtle indications of aging in the face. Not just an ordinary old man, however, but a kalos geron, like the

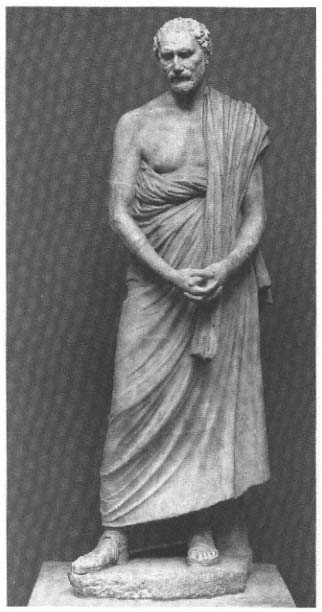

Fig. 30

Portrait herm of the playwright Euripides. Roman copy

of a statue ca. 330 B.C. Naples, Museo Nazionale.

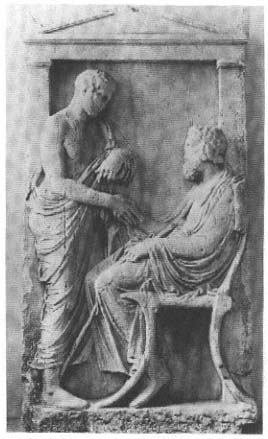

earlier portrait of Homer. In the highly conventional vocabulary of Attic gravestones, this type of old man is often shown seated, especially when he is the principal person being commemorated. (fig. 31). This is an allusion not just to physical weakness, but to the status and authority of the older man within the family (oikos ) and the polis.[21] The dignified, seated position of the elderly paterfamilias is, furthermore,

Fig. 31

Attic gravestone of Hippomachos and Kallias.

Piraeus, Museum.

an accurate reflection of the rituals of daily life. We may be reminded of the dignified figure of old Kephalos, at the beginning of Plato's Republic, who receives his guests seated on a diphros (Rep. 328C, 329E).

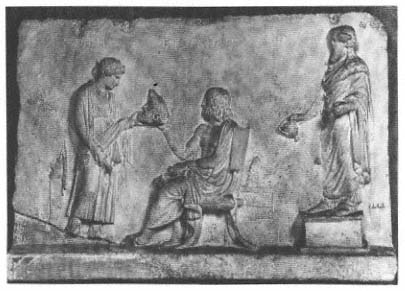

The portrait of Euripides of the Farnese type actually appears once on a seated figure, on a relief of the first century B.C. (fig. 32), which, on the basis of other elements, such as the chair and the overall style, could reflect an original of the late fourth century. The figure is com-

Fig. 32

Votive relief (?) of the seated Euripides, with the personification of the stage

(Skene ) and an archaistic statue of Dionysus. Istanbul, Archaeological Museum.

bined with two that are stylistically later in date, a personification of the stage (Skene ) and an archaizing statue of Dionysus, an eclectic mixture in which, we may well suspect, lurks a quotation of a well-known Classical portrait statue of a poet. Indeed, the classicistic artists of such reliefs as a rule did not "invent" any new figure types. The book roll and the pillow are already elements in the iconography of Late Classical grave stelai. And the mantle drawn up over the back, a standard characteristic of old men, as we see it on the herm in Naples, find a parallel on this relief.[22] In his raised right hand, Euripides takes a mask proffered to him by Skene . In the original portrait statue, to judge from the iconography of the gravestones, that hand could have held the old man's staff.

If we imagine the Euripides statue in this way, then we may well ask why he alone of the three tragedians was shown as an old man. It is

true, of course, that Euripides lived to be eighty, but then Sophocles was ninety, and Aeschylus did not die young either. Euripides in his lifetime was clearly ranked behind Aeschylus and Sophocles and was even accused by his contemporary Aristophanes of lacking any citizen virtues. But in the course of the fourth century, his reputation underwent an enormous transformation, so that by the time of Lycurgus he was considered the most outstanding of the great tragedians (Aristotle calls him tragikotatos at Poetics 1453a29f). For Plato and Aeschines he was simply the wise poet, and later he would even be called by Athenaeus the philosopher of the stage (skenikos philosophos ).[23] Wisdom and insight are precisely the qualities that set the elderly apart from younger men; this is why they enjoyed special privileges both in the life of the city and within the family. So, for example, men over fifty had the right to speak first in the Assembly (Aeschin. In Tim. 23).[24] Not by accident, the relatively few instances on Attic gravestones of this period of a figure holding a book roll are always seated older men like Euripides. That is, they are the only individuals in this highly stylized medium of the bourgeois self-image who are celebrated for their education and knowledge. The aged Euripides would thus have been shown seated to emphasize his extraordinary wisdom relative to the other two tragedians. When we try to imagine the three as a single monument, rather than as separate statues, a grouping of two standing figures and one seated would, by the standards of the gravestones, be a perfectly acceptable one.

If this was indeed the principal message conveyed by Euripides' portrait, we might well expect in his facial physiognomy a clear characterization as an intellectual. Scholars have often seen in this face framed by heavy locks of hair an expression of the supposed melancholy and pessimism that were attributed to Euripides even in antiquity on the basis of his plays, or, at least, as Luca Giuliani recently put it, a definite "Denkermimik."[25] But, once again, modern viewers, influenced by their own expectations, see more than the artist actually intended. Euripides is shown as an older man, and, as on some images of old men on the gravestones, the barely visible wrinkles in the forehead and the eyebrows gently drawn together may suggest a certain element of mental effort or contemplation, but nothing more. A comparison with

the earlier portraits of intellectuals, such as those of Pindar (fig. 7), Lysias, and Thucydides (fig. 42),[26] makes it clear that the sculptor was in no way trying to express a specific kind of mental concentration. On the contrary, the very "normality" of Euripides' old man's face presumably once again reflects the statue's true intentions. Like Aeschylus and Sophocles, Euripides is portrayed as an Athenian citizen, a venerated ancestor, just like those so prominently displayed on the grave monuments of wealthy families at the Dipylon. It seems appropriate, in this context, that in his one preserved oration Lycurgus praises Euripides not so much as a poet, but rather as a patriot, because he presented to the citizenry the deeds of their forefathers as paradeigmata "so that through the sight and the contemplation of these a love of the fatherland would be awakened in them."[27]

Thus in the monument proposed by Lycurgus in the very place where the Assembly met, the three famous poets were presented as exemplars of the model Athenian citizen, probably in three different guises: Sophocles as the citizen who is politically engagé, Aeschylus as the quiet citizen in the prime of life, and Euripides as the experienced and contemplative old man. Their authority, of course, grew out of their fame as poets, yet they are celebrated not for this, but instead as embodiments of the model Athenian citizen.

I should add that most of what I have been suggesting remains valid even if one questions the identification of the portrait of Aeschylus or the association of the portrait of Euripides with Lycurgus' dedication. Even if the context were otherwise, as we shall see, nothing would change in the basic conception of these portraits. The only loss would be in the programmatic interpretation within the framework of Lycurgus' political goals.

A Revised Portrait of Socrates

The Lycurgan program for the patriotic renewal of Athens was all-encompassing. Practical measures for protecting trade and rebuilding offensive and defensive military capability went hand in hand with an attempt at a moral renewal. Religious festivals and rituals were revived

and given added splendor; new temples were built, and old ones renovated. The political center of the city was given a new prominence through a deliberate campaign of beautification that turned the most symbolically charged structures into a stage setting for the city and its institutions. Thus the Theatre of Dionysus, the Pynx, and the gymnasium in the Lyceum were all rebuilt and expanded, as were other buildings and commemorative monuments such as the state burials of the fifth century. Just as in the time of Pericles, the city's physical appearance, its public processions, and publicly displayed statuary were all conceived as parts of an overall manifestation of traditional institutions.[28]

But whereas fifth-century Athens had been a society oriented toward the future, now the city was essentially backward-looking in its desire to preserve and protect. The reminders of the past were intended to strengthen solidarity in the present and increase awareness of the political and cultural values of the democratic constitution now under siege by the Macedonian king and his supporters in the city. The past was to be brought into the present, to make people conscious of their cultural and political heritage. It is no coincidence that in these same years a cult of Demokratia was installed in the Agora and a new monument of the Eponymous Heroes was erected in front of the Bouleuterion.[29] It was in this political and cultural climate that the statues of the great tragedians were put up. They too were intended to strengthen the sense of communal identity and to provide a model for the kind of good citizens that the city needed.

The statues of the three playwrights were not the only examples of retrospective honorific monuments in this period. It is possible that the new statue of Socrates was created as part of the Lycurgan program of renewal. Unlike the portrait with the silen's mask set up shortly after the philosopher's death, this was a statue commissioned by the popular Assembly and erected in a public building. It is reported that the commission to make the statue went to the most famous sculptor of the day, Lysippus of Sicyon (D. L. 2.43).[30]

Alongside numerous copies of the head, we are fortunate enough in this instance to have one rendering of the body, though only in a small-scale statuette (fig. 33). Socrates is now depicted no longer as the

Fig. 33

Socrates. Small-scale Roman copy of an original of the late

fourth century B.C. H: 27.5 cm. London, British Museum.

outsider, but rather once again as the model citizen. He wears his himation draped over the body comme il faut and holds firmly both the overfold in his right hand and the excess fabric draped over the shoulder in his left so that this artful arrangement will not come undone when he walks. These gestures, which seem so natural and insignificant, are in fact, to judge from the gravestones and votive reliefs, part of the extensive code of required behavior that carried moral connotations as well. Careful attention to the proper draping of the garment and a handsome pattern of folds are an outward manifestation of the "interior order" expected of the good citizen. In the pictorial vocabulary, such traits become symbols of moral worth, and, in the statue of Socrates, this connotation is particularly emphasized by the similar gesture of both hands.[31]

The philosopher who was once likened to a silen now stands in the Classical contrapposto pose, his body well proportioned, essentially no different from the Athenian citizens on grave stelai like that of Korallion (fig. 34). The body is devoid of any trace of the famed ugliness that his friends occasionally evoked, the fat paunch, the short legs, or the waddling gait. If we assume for the earlier portrait of Socrates, as I have previously suggested, a body type to match the Silenus-like physiognomy of the face, then the process of beautification, or rather of assimilation to the norm, represented by Lysippus' statue would have been most striking in a comparison of the earlier and later bodies.

The same is true for the head and face, although here the later type does take account of the earlier by adopting some of the supposedly ugly features of the silen (fig. 35). These had by now most likely become fixed elements of Socrates' physiognomy. If we suppose that Lysippus was consciously reshaping the older portrait of Socrates, then the procedure he followed in doing so becomes much clearer. The provocative quality of the silen's mask has disappeared, and the face is, as far as possible, assimilated to that of a mature citizen. Hair and beard are the decisive elements in this process of beautification. They set the face within a harmonious frame. The long locks now fall casually from the head and temples, and the few locks at the crown are made fluffy, so that the baldness looks rather like a high forehead. The face itself is

Fig. 34

Grave stele of Korallion. Athens, Kerameikos.

articulated with more traits of old age than was the case with the silen's mask. Some of the copyists even heightened this tendency of the original portrait, turning Socrates into a noble old man. Thus by the later fourth century, Socrates is no longer the antiestablishment, marginalized figure or the teacher of wisdom with the face of a silen, but simply a good Athenian citizen.[32]

The setting of this statue is no less remarkable than the makeover of Socrates' image. According to Diogenes Laertius (2.43), the statue stood in the Pompeion. This was a substantial building fitted into the

Fig. 35

Portrait of Socrates (Type B). Roman copy

after the same original as the statuette in fig.

33. Paris, Louvre.

space between the Sacred Gate and the Dipylon. Its purpose, as its name implies, was to serve as a gathering place for the great religious processions at the Panathenaea. Another of its functions seems to have involved the training of the Athenian ephebes. Pinakes with portraits of Isocrates and the comic poets, including Menander, suggest that the building played some role in the intellectual life of the city as well. It is even possible that the Pompeion was restored by Lycurgus at the same time as the nearby city wall.[33] In any event, Socrates was to be honored at one of the key centers of religious life and the education of the young. The man once condemned for denying the gods and corrupting the young had become the very symbol of Attic paideia, presented as the embodiment of citizen virtues, a model for the youth!

A General in Mufti: Models from the Past

It was not only the great intellectuals who received such monuments as part of this collective act of remembrance, but other famous Athenians from the city's glorious past. A good example is the posthumous statue of Miltiades, who had led the Athenians to victory over the Persians at Marathon. Unfortunately, only three copies of middling quality preserve the head of the statue created about the middle of the fourth century or a bit later.[34] Despite the rather limited evidence at our disposal, we may make one important inference on the basis of an inscribed herm in Ravenna (fig. 36): the great general was not depicted in helmet or nude, or in armor, as would be usual in the fifth century, but rather in a civilian's mantle, like Socrates and the tragedians. The programmatic message is unmistakable: even the victor of Marathon, after his great triumph over the Persians, had returned to civilian life, an exemplary member of the democracy in the spirit of egalitarianism (his conviction for treason and subsequent death in prison conveniently forgotten). This message is here underlined by the particularly expressionless face, which, when put alongside portraits such as those of Pericles and Anacreon, can signify only a complete self-control. The transformation of Miltiades into an average citizen is all the more extraordinary in as much as the Athenians had long been familiar with portraits of strategoi who were depicted as such, and, as the example of Archidamus makes clear, knew well what the face of a man bent on power could look like.[35]

The statue of Militiades will most likely also have been set up by the polis. Indeed Pausanias (1.18.3) saw in the Prytaneion statues of both Militiades and the other victor over the Persians, Themistocles. And both had been reused by the Athenians in the Imperial period to honor contemporary benefactors, one a Roman, the other a Thracian—a not-uncommon frugality. Pausanias' comment on the "rededication" of the statues is a strong argument for identifying the original Militiades with the type preserved in the herm copy. Assuming the statue was a standard figure in long mantle, the reuse would simply have been a matter of replacing or reworking the head, whereas a nude or armed

Fig. 36

Herm of the general Miltiades. Antonine

copy of a portrait statue ca. 330 B.C.

Ravenna, Museo Nazionale.

statue of the strategos would have presented much greater problems.[36] When we consider all the traditional political associations of the Prytaneion, it seems a reasonable supposition that these two statues of great commanders also belong to the time of Lycurgus. This cannot, however, be confirmed by stylistic arguments, since the portrait of Miltiades could date as early as ca. 360 B.C.

Quite apart from the question of its date, the portrait of Miltiades once more lends support to our interpretation of the statues of the tragedians in the Theatre of Dionysus, as well as that of Socrates in the Pompeion, as paradigms of the good Athenian citizen. In these honorific monuments, the intellectual qualities of the great writers and philosophers of old were of as little concern as the martial valor of the generals. Rather, by representing the great Athenians of the previous century as if they were outstanding contemporaries instead of giants of a bygone era, the impression was created of a seamless continuity between past and present. We are dealing here with a self-conscious act of collective memory, not with a nostalgic reverence for remote and inimitable figures, as will be the case later on.

This attempt to recall and incorporate the great men of Athens's past in the present had not, however, started with Lycurgus. Portraits honoring Lysias and Thucydides, whose furrowed brows we shall return to shortly, had been put up a generation or two before Lycurgus' dedication of the tragedians.[37] Some time after Lycurgus, apparently, statues of the Seven Wise Men were put up, again in the guise of distinguished contemporaries: even Periander, tyrant of Corinth, was converted into a good citizen (fig. 37)![38] Indeed, we may suppose that almost all portrait statues of the great men of the fifth century that were put up in Athens in the fourth century had the same kind of exemplary function. But under Lycurgus this form of didactic retrospection, when coupled with other measures, first took on a particularly programmatic character. Thus it makes little difference for our understanding of them whether the statues of Socrates or Miltiades actually belong ten or twenty years earlier or later.

The Athenians always felt that their loss of primacy in the political and military sphere was compensated by a cultural superiority to other Greeks, evidenced in their democratic constitution and the Attic way of life that they considered unique, as well as in specific accomplishments such as the staging of great festivals, the Periclean buildings on the Acropolis, and even the works of the great playwrights. The strategies employed to sustain this notion included the elevation of daily life to the level of aesthetic experience, along with the continual cultivation of the memory of the great events and figures of the past. In the

Fig. 37

Herm of Periander, tyrant of Corinth, as one

of the Seven Wise Men. Antonine copy of a

portrait statue of the late fourth century B.C.

Rome, Vatican Museums.

visual arts of the fourth century we can already detect conscious evocations of High Classical style, so that the act of memory is cloaked in the appropriate artistic form.[39] The programmatic idea of a comprehensive paideia, as propagated by Isocrates, and the notion of Athens as the "school of Hellas" are both slogans that attest to the remarkable success of these efforts. After the collapse of their imperial aspirations, the Athenians succeeded in establishing a claim to cultural preeminence that they kept intact virtually to the end of antiquity. Later on we shall see how this phenomenon influenced the way many intellectuals saw themselves, even under the Roman Empire.

Plato's Serious Expression: Contemplation as a Civic Virtue?

Thus far we have dealt only with retrospective portraits and must now ask, how did contemporary intellectuals in fourth-century Athens have themselves portrayed? What was the relation between their own self-image and the way they presented themselves? Certainly Plato and Isocrates were no more lacking in self-assurance than the Sophists. By about 420–410 B.C. , Gorgias had dedicated a gilded statue of himself in Delphi, prominently displayed on a tall column (Pliny HN 33.83; Paus. 10.18.7).[40] Both the separation of the intellectual from society at large and at the same time the claim to a position of leadership in the state had, if anything, increased since the days of the Sophists. The formation of large circles of disciples in the rhetorical schools and around the philosophers, as well as the partial withdrawal of these schools from public life, their rivalries and their vigorous criticism of the status quo, had in the course of the fourth century led to a situation in which both teachers and pupils attracted the attention of the public even more than in the time of Aristophanes. The great interest that the comic poets took in contemporary philosophers attests to their vivid presence in the public consciousness.[41]

By coincidence, we hear in our sources of two impressive funerary monuments in the decade 350–340, in both of which the intellectual activity of the deceased was explicitly commemorated. One was a

monument for Theodectes, the poet from Phaselis, with statues of the most famous poets of the past, starting with Homer. The other was the family tomb monument of Isocrates, which had portraits in relief of his teachers, including Gorgias instructing the young Isocrates at an astronomical globe—a motif known to us from later works. Thus the great orator continued even in death to broadcast his plea for a universal paideia . Did these men's contemporaries perceive such tombs as being at odds with the social ideal of equality? Is it just accidental that both tombs are private monuments for men with well-known royalist sympathies? Isocrates was said to have congratulated Philip of Macedon on his victory at Chaeronea, and Theodectes seems to have been a favorite of Alexander's.[42]

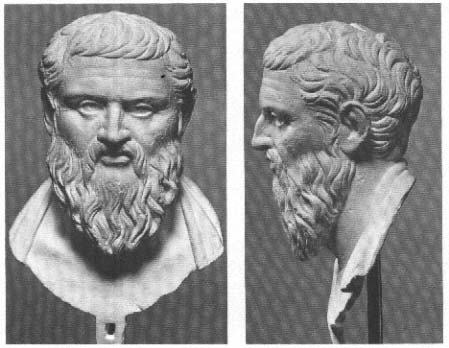

In these circumstances, we might have expected that the portraiture of such self-assured individuals would make direct reference to their intellectual claims and abilities, whether in dress and pose or facial expression, beard, or hairstyle. Unfortunately the pitiful state of our evidence does not permit any definite answers, especially with regard to body types. While we have a whole series of head types, we have not one body that can be identified as belonging to a portrait of a contemporary intellectual of the fourth century. We may, however, suppose that their bodies looked little different from those of the retrospective portraits of the famous poets or of Socrates or, for that matter, of the male citizen on the gravestones. This is, at least, what we would expect from what we know of their heads. This brings us back to the difficult question of how to interpret Plato's expression in his famous portrait type (figs. 24, 38).[43]

A small bronze bust, only fifteen centimeters high, that recently appeared on the art market has considerably enriched our understanding of the original Plato portrait (fig. 39a, b).[44] This version has an aquiline nose, erect head, and the mantle falling over the nape of the neck and the shoulders. Plato is portrayed as a mature man, but not elderly. His hair does not fall in long strands, like that of Euripides, but rather is trimmed into even, fairly short locks. His beard is long and carefully tended, similar to Miltiades' (see fig. 36). The only clear signs of age are the sharp creases radiating from the nose and the loose, fleshy

Fig. 38

Portrait of Plato, as in fig. 24. Munich, Glyptothek.

cheeks. Both style and characterization suggest that the portrait could well have been created during Plato's own lifetime and not, as usually assumed, after his death in 348/7.[45] Perhaps the original is to be identified with a statue set up in the Academy by one Mithridates, presumably a pupil of Plato's, whose inscription is recorded by Diogenes Laertius: "The Persian Mithridates, son of Rhodobatos, dedicates this likeness of Plato to the Muses. It is a work of Silanion" (3.25). It was,

Fig. 39 a–b

Small bronze bust of Plato, from the same original as fig. 38. Kassel,

Staatliche Kunstsammlungen (from a cast).

then, a votive to the Muses, like the portrait of Aristotle (D. L. 5.51), and would have stood in the shrine of the Muses in the Academy, though it is not clear whether this shrine was the one in the public gymnasium of that name or in Plato's gardens nearby.

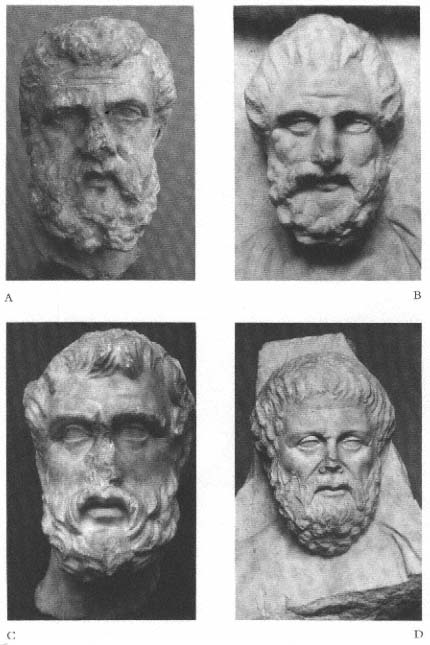

The serious expression of the face is created primarily by the two horizontal lines across the brow and the drawing together of the eyebrows, forming two short vertical lines above the ridge of the nose. This network of wrinkles, however, which is only hinted at in some copies, as in Munich, but more deeply engraved in others, is a widespread formula. It occurs in most intellectual portraits of the fourth

Fig. 40

Portrait of Sophocles. Detail

of the statue in fig. 25.

Fig. 41

Portrait of Aristotle (384–322). Roman

copy of a statue of the late fourth century

B.C. Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum.

century, more or less pronounced, whether for Aristotle (fig. 41) or Thucydides (fig. 42). Theophrastus (fig. 43), the tragedians dedicated by Lycurgus, or Socrates. One could even think back to the mid-fifth-century portrait of Pindar. At that time, however, it had been standard practice, at least in Athens, not to include any indications of effort or emotion in citizen portraits, as we saw attested in the images of Anacreon and Pericles. The serious expression of Plato is therefore an innovation of the fourth century, a departure from, or rather a relaxation of, the earlier convention.

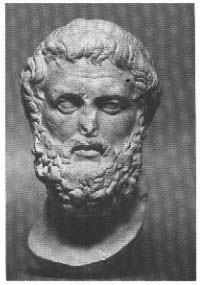

Nevertheless, for the contemporary observer, this trait cannot have been a specific and exclusive indicator of intellectual activity, for the expressions of mature male citizens on Attic grave stelai often have a similar character, and it is hardly possible in each individual case to

Fig. 42

Portrait of the historian Thucydides

(ca. 460–400). Roman copy of a statue of

the mid-fourth century B.C. Holkham Hall.

Fig. 43

Portrait herm of Theophrastus

(ca. 372–288). Roman copy of a statue

ca. 300 B.C. Rome, Villa Albani.

be certain if it is really meant to convey an air of introspection (fig. 44a–d).[46]

As Giuliani has shown, such a serious expression, with the brows drawn together, could have been understood at this time as signifying intelligence and thoughtfulness. In our sources, even a young man is counseled to appear in public with such a countenance.[47] But this particular quality is never mentioned in isolation by contemporary authors, rather always in the context of other traditional expressions of the well-bred Athenian citizen, such as a measured gait, modest demeanor in public, and modulated voice. And these are the very standards of behavior, as we have seen, by which the morally correct citizen, the kaloskagathos, was measured. In other words, the canon of citizen virtues, already well attested in the time of Pericles, was

Fig. 44 a–d

Four portraits of mature Athenian citizens from grave stelai of the later fourth

century B.C. : a, Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek; b, Athens, National Museum;

c and d, Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek.

enhanced in the course of the fourth century with an additional intellectual quality embodied in the new facial expression.

We may well imagine that some well-known intellectuals in Athens, and even more likely their pupils, did indeed cultivate such a serious demeanor in their public appearances, for which they were ridiculed by the comic poets.[48] But this did not stop the admirers of the great masters from having them portrayed with an introspective look, even if, as in Plato's case, so subtly that the basic citizen image is barely altered. We must once again remind ourselves that we tend to see these portraits too close up. No contemporary viewer would have perceived the facial expression in the disconnected fashion we do, when we stare at a photograph and look for the wrinkles. He always saw the face as but one element of the whole statue. As writers of the time attest, the serious expression was not the primary component, rather an extra touch in the traditional citizen image.

Unfortunately, no copy of the body belonging to the statue of Plato has yet come to light, though we may assume that it was somewhat similar to that of Socrates (see fig. 33). Since Plato is not portrayed as an old man, the gravestones would lead us to think that he could hardly have been shown seated in the manner that, as we shall see, first appears with the most authoritative Hellenistic thinkers. Like that of Aristotle and other philosophers of the Classical period, Plato's teaching style involved much physical movement (D. L. 3.27). The dialogue was more than just a literary genre.[49]

But the most interesting aspect of this whole issue is the way in which the serious expression of the philosophers is transferred to the nonspecific citizen image. That this could occur at all presumes that, in spite of the mocking of the comic poets, the new visual formula carried basically positive associations. The fact, however, that the lined forehead and drawn-together brows occur on the grave stelai primarily for elderly and even older men makes the formula even less specific. That is, even if this trait was originally intended for the portraits of intellectuals as the mark of the thinker, this cannot apply equally to all the faces of older citizens that now display it. For them, it inevitably becomes a vague and ambiguous formula, which can express strain as well as introspection, perhaps sometimes even grief or pain. For the

ancient viewer whose eye was accustomed to these images, Plato's expression would lose any specific significance and could hardly convey "a considerable degree of specialized mental activity as the general characteristic of the intellectual."[50]

The great impression made by the publicly known intellectuals of the fourth century on their fellow Athenians can perhaps be inferred from yet another remarkable phenomenon. Among the portraits of anonymous older men on the grave stelai can be found a number of faces that are strikingly similar to those of famous intellectuals. A portrait of an old man in Copenhagen, for example, once part of a grave stele, recalls the portrait of Plato so closely that one could almost ask if this were the philosopher's own tomb monument (fig. 44d).[51] But this is unlikely on typological grounds alone, since older men like this one with the same expression are usually subsidiary figures in the background. Furthermore, this is not a unique instance. Other heads on gravestones recall the portraits of Aristotle (fig. 44b), Theophrastus, and Demosthenes, while at the same time the unsurpassed artistic dimension of these portraits, compared with the grave reliefs, with their new means of expressing personality, is obvious.[52] Such similarities between the portraits of intellectuals and those of ordinary Athenians suggest that not only their meditative expressions but also certain individual physiognomic features of the famous philosophers and rhetoricians were so familiar and widely admired that some of their contemporaries affected similar styles of hair, dress, and bearing. We hear in the literary sources, for example, that Plato's followers were made fun of for imitating his hunched stance, and in the Lyceum some of Aristotle's distinguished students adopted the master's lisp (Plut. Mor. 26B, 53C). Theophrastus is a good example of just how popular an intellectual figure could become in Athens: people came in droves to his lectures, and half the city took part in his funeral (D. L. 5.37, 41).

If what I have been suggesting is true, it would imply that Classical portraits, while adhering closely to a standard typology, do nevertheless occasionally reproduce actual features of the subject's physiognomy—in Plato's case, the broad forehead and the straight line of the brow, in Aristotle's; the small eyes (which are also mentioned in the

literary sources). Athenian citizens will have similarly imitated even more eagerly the faces of influential statesmen and other well-known and well-liked personalities. The fact, however, that such assimilation is attested only in the portraiture of intellectuals is probably to be explained by the choices made by the proprietors of Roman villas for their collections of portrait busts (cf. pp. 203ff). Viewed as a whole, Athenian portraiture of the fourth century experienced a continual and pervasive process of differentiation in facial types. The driving force behind this may well have been the urge to assimilate to the likeness of famous individuals.

We may, then, reaffirm that Plato was depicted not as a philosopher, but simply as a good Athenian citizen (in the sense of an exemplary embodiment of the norms), and this is true of all other intellectuals of fourth-century Athens for whom we have preserved portraits. Nor was Plato's expression likely to have been read by his contemporaries as a reference to particular intellectual abilities.

Furthermore, Plato's beard was, at the time, not yet the "philosopher's beard," but the normal style worn by all citizen men. It was only by the Romans that it was first interpreted as a philosopher's beard, a point seldom recognized in archaeological scholarship (cf. pp. 108ff.). Nevertheless, the length of Plato's beard has rightly caused some puzzlement.[53] On the gravestones, it is primarily the old men who wear such a long beard, while those who, like Plato, have not yet reached old age tend to wear it trimmed shorter.[54] Given the extraordinarily high degree of conformity in Athenian society, such deviations could certainly be meaningful. The key may be contained in an often-adduced fragment of the comic poet Ephippus, a contemporary of Plato's, who makes fun of one of Plato's more pompous pupils, whom he describes as hpoplatonikos (frag. 14 = Ath. 9.509B).[55] His chief characteristics include an elegant posture, expensive clothing, sandals with fancy laces, carefully trimmed hair, and a beard grown "to its natural length." Even this, however, does not imply a specifically self-styled philosopher, but rather a noticeably elegant and soigné appearance characteristic of some of Plato's pupils. As would later be true of the Peripatetics, the members of the Academy evidently valued a

distinguished, not to say "aristocratic," appearance. The portrait of Plato makes the same statement, when one considers especially how carefully cut and arranged the hair is across the forehead, as well as the beard, which is, strictly speaking, too long for a man of his age. if, then, there is anything about the portrait of Plato that suggests a subtle differentiation from the norm, it would be in the realm of aristocratic distinction.

The search for the portraiture of intellectuals in fourth-century Athens leads finally to a kind of dead end. We find an extraordinary situation, in which both Athenian citizens and outsiders, quite independently of their profession or social status, and even including critics of the state and its institutions such as Plato and his pupils, identified with a highly conformist citizen image. This identification was entirely voluntary and is equally applicable to publicly and privately displayed monuments. There must have existed a general consensus on the moral standards embodied in this citizen image. The phenomenon may be likened to that of the standard houses of uniform size that we find in newly planned Greek cities.[56] In both instances, aesthetic symbols express a notion of the proper social order that has been fully internalized, independently of the current political situation at any given time. Even for the famous teachers of rhetoric and philosophy, with their high opinions of their own worth, the message "I am a good citizen" was evidently more important than any reference to their abilities or self-perception as intellectuals. In fact, as the votive and funerary reliefs attest, they were no different in this respect from the craftsmen and other fellow citizens who followed a specific profession or enjoyed a particular status.[57]

Political Upheaval and the End of the Classical Citizen Image:

Menander and Demosthenes

After the death of Alexander, Athens's political stability was shaken by a seemingly endless series of reversals. For several generations, oligarchic and tyrannical regimes alternated with democratic ones, both moderate and radical, each often lasting no more than a few years.

Nearly every change of government brought with it the exile or return from exile of then main protagonists.[58] It is only natural to suppose that these constant political volte-faces had a destabilizing effect on the general mood and the acceptance of traditional standards of behavior in the democratic state. This insecurity would especially have infected the relationship between the individual and the community, creating an urgent need for a new spiritual orientation independent of political values.

In these circumstances, the traditional image of the Athenian citizen also experienced a kind of crisis. I should like to demonstrate this with two exemplary cases, the statues of the comic poet Menander and the orator Demosthenes, both public honorary monuments for which we can reconstruct reasonably well the original location and the historical circumstances. Both statues are rightly regarded as cornerstones of Early Hellenistic art. I wish to place them here alongside the Late Classical portraits of Sophocles and Aeschines primarily to illustrate once again, by means of the contrast, the peculiarly self-contained nature of the Classical citizen image. The values and desires expressed in these new monuments were not in themselves new, but they could, it seems, find public recognition only in the changed political circumstances. In retrospect, this only confirms the suspicion that the moral standards embodied in the imagery of the Classical citizen were a direct concomitant of the democratic political consciousness.

The statue of the comic poet Menander was put up most probably soon after his death in 293/2, in the Theatre of Dionysus in Athens, in a prominent spot at one of the principal entrances. According to the preserved inscription, it was the work of two sons of the renowned Praxiteles, Kephisodotus the Younger and Timarchus. I will pass over the complicated history of the transmission of this portrait type and instead take as my starting point the results of the recent reconstruction by Klaus Fittschen, imaginatively realized with the help of plaster casts (fig. 45).[59] Because, however, the reconstruction still does not give the complete picture (since it is impossible to take account of all the copies at once), a more extensive description will be necessary, to

Fig. 45

Honorific statue of the poet Menander (342–293).

Reconstruction by K. Fittschen with the help of plaster

casts. Göttingen University, Archäologisches Institut.

give an idea of the full state of our evidence as transmitted by the copies.

Everything about this statue runs contrary to the old ideals. The poet, who died at fifty-two, is shown as approximately that age, yet he is seated on a high-backed chair that, on Classical grave stelai, had been reserved for women and elderly men. The seated motif has now taken on an entirely new set of connotations. The poet is presented to us as a private individual who cultivates a relaxed and luxurious way of life.

The chair is a handsome piece of furniture, with delicate ornament. The domestic ambience is underlined by the footstool, slid in at an angle, and the overstuffed cushion that overlaps the sides. Later on we shall see what an important role these cushions play in the iconography of the poet.

Menander sits upright, his garment carefully draped, yet his posture fully relaxed. His legs are positioned comfortably, one forward, the other back, the right arm resting in his lap, and the left descending to the pillow. His shoulders are drawn together, and the head is lowered and, in an involuntary movement, turned to the side. The poet gazes out, as if lost in thought, unaccompanied and unobserved. Why, then, has the artist attached such importance to his handsome appearance and to portraying his calm and idyllic existence? His outfit is also very different from that of earlier portrait statues. The undergarment that he wears would have been considered effeminate in the time of Lycurgus. In addition, the himation is much more voluminous than before, the excess fabric arranged so casually and yet artfully and elegantly as to give the play of folds their full effect. On his feet are handsome sandals with a protective strap over the toes.

The hairstyle, "casually elegant," in the words of Franz Studniczka, betrays a deliberate concern for careful grooming, while the clean-shaven face takes up the fashion introduced by Alexander and the Macedonians, and must be understood as the sign of a soft and luxurious life-style (cf. p. 108).

We have already noted how variable the face of Menander is in the different copies. Of the seventy-one copies recently compiled by Fittschen, there is not one that can simply be assumed to be most faithful to the original. It must somehow have conveyed youthful beauty as well as exertion, have been both distanced and introspective. Two busts, in Venice (fig. 46) and Copenhagen (fig. 47), may provide the two poles between which we should imagine the original. The face is, in any event, expressive and personal in an utterly new way.[60] The artist allows the viewer a glimpse into the private realm of the subject. The public and impersonal character of the statue of Sophocles (fig. 25) becomes in retrospect even clearer.

The whole portrait matches rather well what we hear in our sources about the poet's manner and personal style. The most revealing anecdote relates Menander's appearance before Demetrius Poliorcetes, when he hurried to welcome the new ruler. "Reeking of perfume," as Phaedrus writes, he pranced before the new overlord of Athens in long, flowing robes, swiveling his hips, so that the Macedonian at first took him for a pederast, before he heard who he was. But then he too was impressed by Menander's extraordinary beauty (Phaedr. 5. 1). Incidentally the contemporary source from which this quotation must derive specifically mentioned that Menander entered the king's presence with a group of "private individuals" (sequentes otium ), which implies that they were already recognized as a particular segment of society.

The statue of Menander, in its appearance and the way of life it reflects, embodies the very type so repugnant to the radical democrats: the wealthy and elegant connoisseur who withdraws entirely from public life. As is well known, Menander's comedies are essentially apolitical renderings of everyday life. If we can trust later sources, this image seems to be an accurate reflection of his own life. Evidently he did not even live in the city but deliberately withdrew to the Piraeus with his lover, to enjoy a nonconformist way of life.[61] And in this respect Menander was not alone. Earlier on, in the Peripatos, the philosophical school with royalist leanings where Menander studied together with his friend Demetrius of Phaleron, an elegant and luxurious style was highly prized. Even Aristotle was said to have called attention to himself by wearing many rings (Ael. VH 3. 19). When Demetrius of Phaleron ruled Athens as regent of the Macedonian Kassander (317–307 B.C. ), he was accused of leading a decadent life filled with lavish banquets, beautiful courtesans, and expensive racehorses. And it is unimaginable that the extravagant life-style of Demetrius Poliorcetes did not make a deep impression on the Athenians. Surely some of this will have rubbed off on the wealthier Athenians during his long stays in the city. Thus arose the cult of tryphe, a gay joie de vivre associated with this particular circle, a style that would soon become emblematic of the royal image of the Ptolemies in Egypt.[62]

Fig. 46

Bust of Menander. Venice, Seminario Patriarchale. (Cast.)

But the monument to Menander was set up by the Athenian people, at a conspicuous location, and even stood on a tall base that emphasized its official character. If the figure celebrates elements of a particular way of life, we cannot dismiss these as the traits of one famous individual who was looked on as an outsider in Athens. Rather, the oligarchy now in power, installed by Demetrius Poliorcetes, chose to celebrate a way of life that had always been cultivated at the courts of kings and tyrants but was anathema to the democratic polis. Certainly Lycurgan Athens would not have put up a statue to a man like this or at least would never have celebrated in him these particular qualities.

Fig. 47

Augustan copy of the portrait of Menander.

Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek.

The occasion for the statue was once again, as in the case of Lycurgus' honors for the tragic poets, the great fame and popularity of Menander's work, yet he is not portrayed as a poet. What his friends admired most about him was rather his way of life. Thus Menander's statue can also be seen as a kind of role model, not, however, for a polis oriented toward the ideal of civil egalitarianism, but only for a small segment of wealthy oligarchs and their sympathizers. Or were these now perhaps in the majority?

The statue of Demosthenes, by the otherwise unknown sculptor Polyeuktos, put up about a decade later, may be seen as a counterpoint to the Menander portrait, emanating from the camp of the democrats (fig. 48).[63] The simple garment and beard reflect once

Fig. 48

Statue of Demosthenes (ca. 384–322). Roman copy of the

honorific statue set up in 280/79 B.C. (with the hands correctly

restored). Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek.

again traditional values. But both pose and expression now proclaim for the first time the extraordinary intellectual capacity required for political achievement.

The political situation had once again changed soon after the death of Menander. After 287 the city itself was again free, the old democratic constitution reinstated. Yet there was less room for political maneuvering, so long as a Macedonian garrison remained in the Piraeus. The rehabilitation of Demosthenes, sworn enemy of the Macedonians and defender of freedom, was commissioned by his grandson Demochares, himself a leading democratic politician who had been in exile for seventeen years because he refused to collaborate with the oligarchic regime. The honorific statue of Demosthenes was a clear sign of the renewed Athenian resolve to be independent. The statue's location underlines its political significance. It stood in the middle of the Agora, near the Altar of the Twelve Gods, the famous monument to the goddess Peace, and the statues of Lycurgus and Kallias (Paus. 1.8.2).

Unlike Sophocles and Aeschines, Demosthenes seems to be entirely absorbed in himself. His hands are clasped before him, the head turned to the side, and the gaze directed downward. Despite what looks at first like a quiet pose, the orator is actually shown in a state of extreme mental tension. The brows are almost painfully drawn together, and the position of the arms and legs is not at all relaxed. Everything about the statue is severe and angular, at times even ugly. It has none of the genial quality or self-assured presentation in public of Sophocles or Aeschines (figs. 25, 26). In such a state of concentration, one does not pay attention to the proper fall of the mantle or a graceful posture. Yet Demosthenes' pose cannot be explained simply as a neutral characteristic of the statue's style; rather it expresses a specific message.

As so often in portrait studies, commentators have tried to find biographical clues to the statue's interpretation. The clasped hands are supposed to be a gesture of mourning, to suggest that the failed statesman laments the loss of freedom, a warning to future generations.[64] Yet neither the epigram beneath the statue nor the long accompanying decree gives any hint of failure. The epigram reads: "O Demosthenes, had your power [rhome ] been equal to your foresight [gnome ], then

would the Macedonian Ares never have enslaved the Greeks." The contrast is between gnome and rhome, and Demosthenes is celebrated as a man of determination and insight. Both notions are contained in the word gnome . Since the epigram originated in the circle of the radical democrats, it cannot be taken to imply any criticism of Demosthenes' failure. It merely laments the fact that he did not have access to the necessary military might to implement his political goals.

The statue also celebrates Demosthenes' gnome by rendering the activity in which he won his reputation, as a public speaker.[65] Plutarch reports how excitable Demosthenes became when speaking extemporaneously (as opposed to when he delivered a rehearsed speech). His emotional speaking style was criticized by his opponents as too populist, and Eratosthenes (apud Plutarch) refers contemptuously to the "Bacchic frenzy" in which the orator came before the Assembly. Demetrius of Phaleron is even more specific: "The masses delighted in his lively presentation, while the better class of people found his gestures vulgar and affected" (Plut. Dem. 9.4; see also 11.3).

I believe this passage suggests the correct interpretation of the clasped hands. The statue revives these old accusations of theatrical gestures but refutes them and at the same time praises Demosthenes for his passionate commitment. That is, it asserts, in spite of the extreme effort and concentration of the great patriotic speeches, the speaker never lost his self-control. He grasps his hands firmly before him to show that he has mastered his emotions. Though extremely tense, he does not move his arms, and the mantle remains properly draped. But he is no actor, like his rival Aeschines, who would assume a rehearsed and artificial pose. Rather than showing himself off, he is concerned only with the matter at hand.

The gesture of the clasped hands has, like most others, multiple meanings in Greek art. It can indicate a high emotional state, as Medea before the murder of her children, but also a state of calm and self-control, as on the gravestones. Its specific meaning must be read from the context. I believe my interpretation is confirmed by the occasional reappearance of the clasped hands motif—and an even stronger version in which the two hands grasp each other tightly—on Hellenistic grave stelai, alongside other formulas for depicting a public appear-

Fig. 49

Bust of Demosthenes. Cyrene, Museum.

ance.[66] The gesture can also be found in some later portrait statues that have already been taken to be those of orators, including two torsos of the High Hellenistic period, where it is so dramatically exaggerated as to suggest the "Asiatic" school of rhetoric: the passionate speaker literally wrings his hands.[67]

The "unprecedented pathos" of Demosthenes' facial expression (fig. 49), as Giuliani observes, is indeed to be understood as "a signal for burning political commitment."[68] This is not the expression of a man in mourning. The contracted brows reflect the struggle to find

Fig. 50

Portrait of the general Olympiodorus.

Roman copy of a portrait ca. 280

B.C. Oslo, National Gallery.

the mot juste. We are witnessing here a new paradigm for expressing intellectual activity, one that we shall soon encounter again in the portraits of the Stoics. A comparison with the very different expression of Olympiodorus (fig. 50), in the portrait of this contemporary general who drove the Macedonians from the Mouseion in 287, makes clear that, after the generalized citizen faces of the fourth century, we are now dealing with a new mode of expression that conveys specific talents and situations. Olympiodorus' expression embodies rhome; Demosthenes', gnome .

Alongside the energy and concentration of Demosthenes, his rival Aeschines' appearance—flawless but utterly lacking in emotion—

looks in retrospect rather insincere, mere surface beauty. It is quite conceivable that the statue of Demosthenes was intended as a kind of countermonument to that of Aeschines (fig. 26). Beside the realism of Demosthenes, Aeschines' pose looks rather theatrical, the undergarment and hairstyle effeminate. The portrait of Demosthenes proclaims instead that genuine achievement is gained through extreme effort, that is (and this is the part that is new), intellectual effort. A message of this sort presupposes a very different set of values. The statue's purpose is no longer to present a prescribed model of citizen virtue, but rather to celebrate extraordinary abilities and accomplishments.

With this monument, democratic Athens distances itself from its own earlier ideal of an emotionless kalokagathia . For the first time, an honorific statue of prime political significance celebrates superior intellectual power as the quality of decisive importance. This means, however, that in the representation of Athenian citizens a previously unknown hierarchy becomes apparent. In spite of the many references to earlier tradition, Demosthenes is no longer the exemplary citizen, simply one among equals, like Sophocles and other fourth-century intellectuals. Instead, he is presented as a towering, even heroic figure. Ironically, it was the democratic faction of Demochares that was responsible for this first major break with its own long-cherished image. And this break is but a foretaste of the wholesale shift in values that will reshape the society of the Early Hellenistic age.