The Dual Face of Christ

One of the most remarkable features of Early Christian art is the dual imago Christi . Christ is depicted both as a radiant youth or boy and—

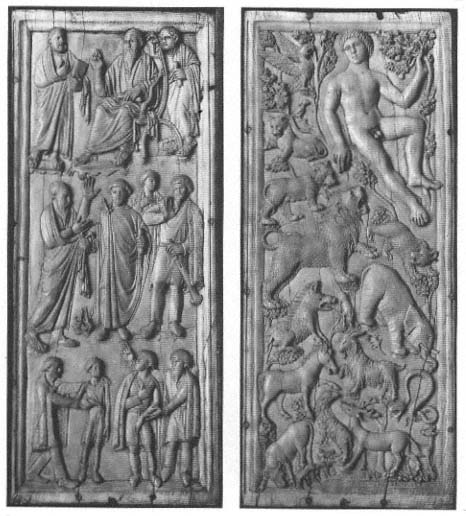

Fig. 161

Ivory diptych showing Paul as teacher and miracle worker and Adam in Paradise.

Ca. A.D. 400. Florence, Bargello.

though much less often at first—with a full beard and shoulder-length hair. Both portrait types can be used in scenes of the same subject, even many times on the same monument, yet no straightforward differentiation in meaning can be discerned.[48] Evidently there was no single, all-embracing image for the figure of Christ in the traditional vocabulary that was considered adequate. Perhaps, then, we should interpret the deliberate juxtaposition of both types as an attempt to capture the totality of Christ's nature through an accumulative process. The phenomenon is of particular interest for our investigation because both portrait types ultimately go back to ideas and pictorial models from the pagan cult of learning.

Let us consider first the youthful Christ. The picture of Christ given by Justin, Tertullian, and Clement of Alexandria is still unremarkable, and it is only in the course of the third century that the image of the beautiful youth appears, probably first among the Gnostics.[49] This is surely an instance of "Hellenization." In the scholarly literature the radiant youth has often been identified with Apollo, but this does not provide a concrete iconographical link, since Apollo's beauty is best revealed in his nude body. Rather, we may recall the tradition of romanticized portraits of young men with long hair of the second century A.D. , which conjured up various Greek heroes from Achilles to Alexander the Great as a kind of nostalgic expression of faith in the revival and preservation of classical culture (cf. fig. 157). Other idealized images of the youth with beautiful long hair may have had an influence as well, such as the Genius Populi Romani .[50] Along with the long-haired youth, we also find not infrequently an even younger, almost childlike image of Christ, not only in some of the more modest catacomb paintings, but also on some especially fine sarcophagi. This is surely somehow related to the type of the intellectual wunderkind, which, as we have seen, was especially popular in Roman funerary art of the later third century (fig. 149). Philostratus and Eunapius also, incidentally, regularly report that the charismatic wise men had been wunderkinder too, distinguished both by their spiritual powers and by extraordinary beauty.

This widespread enthusiasm for the intellectual wunderkind, which only increased as the Empire wore on, represents a definitive break

with the traditions of Greece, where mental powers and wisdom were always associated with advancing age. We are now confronted instead with the notion of a new and miraculous kind of wisdom, something one is born with, a gift, no longer the result of either great mental effort or experience. When these idealized notions of the miracle worker are adopted for the image of Christ, they take on an added dimension. This divine youth, the Son of God, stands for an all-encompassing hope for a new world.

The type of the bearded Christ, on the other hand, has always been recognized as inspired by philosopher iconography. A different avenue of interpretation, which seeks to establish a link to the Classical iconography of the Greek gods, whether Zeus or, as more recently suggested, Asklepios, has rightly found little favor.[51] Nevertheless, I believe it is one particular tradition of philosopher iconography with which we are dealing. His shoulder-length hair clearly separates the bearded Christ from the philosopher portraits of Classical and Hellenistic art and places him instead in another tradition, one that we first encountered in the description of Euphrates (cf. p. 257). As I have tried to demonstrate, this type of portrait, or, rather, the self-image that lies behind it, was meant to translate into visual terms a special aura of dignity, as well as magical and spiritual powers to which these "holy men" lay claim. Of all the guises in which intellectuals of the past had appeared, this one radiated the ultimate authority. Although it has proved impossible to arrive at a clearly defined prototype, both because literary descriptions are vague and contradictory and because the visual evidence from the second century is still rather spotty, I nevertheless remain convinced that the image of the bearded Christ with shoulder-length hair is closely associated with that of the theios aner . The comparison of Christ with the pagan miracle workers, who likewise possessed divine powers and, in their own way, also promised a kind of "salvation," was self-evident and became a favorite topos in the debate between pagans and Christians. It is in the portraiture of the later Charismatic philosophers, who were believed even more "holy" and "divine," that we shall once again encounter the type with shoulder-length hair.

Fig. 162

So-called polychrome plaques, showing Christ performing miracles and at the Sermon

on the Mount. Ca. A.D. 300. Rome, Terme Museum.

The first secure example of a bearded Christ belonging to this tradition is on the "polychrome plaques" made in Rome about A.D. 300 (fig. 162). But there must have been earlier examples, as we can infer from references to the images of Christ of the Karpokratians, who used these as objects of cult worship, along with portraits of Plato, Aristotle, Pythagoras, and others.[52] Christ appears in several scenes on the polychrome plaques as healer or miracle worker, sometimes still depicted as an ascetic philosopher with no undergarment, similar to the figure of the itinerant philosopher in the Herakleion Museum that we saw earlier (fig. 143). In one scene, however, he turns to look out of the picture, gesturing like a public speaker and conspicuously holding aloft a book roll. Several small figures sit listening at his feet, implying that this must be a specific event, such as the Sermon on the Mount. Significantly, in this particular scene Christ's long, thick hair is especially emphasized.

Only about the middle of the fourth century does the image of Christ as the theios aner become widespread on sarcophagi and in catacomb paintings, both in scenes with multiple figures and in the form of painted busts (fig. 163).[53] He is always shown frontally, and both

Fig. 163

Detail of a ceiling fresco in the Catacomb

of Saints Marcellino and Pietro in Rome,

showing Christ teaching between Peter

and Paul. Second half of the fourth century A.D.

beard and hair are particularly lush and carefully tended. The high forehead shows no emotion and is emphasized by the central part. Equally consistent is the immaculately draped garment. All of these traits must be intended to banish any possible association with the "filthy" image of the itinerant Cynic philosopher. Instead, the lavish, dense hair emphasizes his magical powers. The painted portrait busts in the catacombs, which have rightly been said to reflect major works of ecclesiastical art, first present us with the fully formed image of Christ in majesty that will so dominate Byzantine art.

In the time of Theodosius, when the bearded Christ on sarcophagi proclaims his law with a magisterial gesture, the old formula has taken

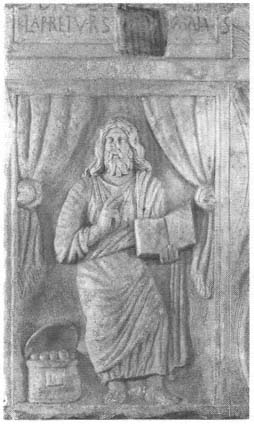

Fig. 164

Strigilated sarcophagus showing Christ as teacher.

Ca. A.D. 370. Rome, Sant'Agnese fuori le mura.

on a new meaning. Yet a more modest strigilated sarcophagus of the same period illustrates how the continuity from the image of the teacher of wisdom has still not been forgotten (fig. 164). As in the earlier scenes with the gathering of pupils, Christ turns directly to the viewer and presents him with the Scripture. The chest of book rolls once again emphasizes the great learning of the teacher. But the

curtains, as in Imperial state art, characterize the site of his epiphany as an impressive public setting. Meanwhile, the lid illustrates that ancient symbol of happiness, the marine thiasos .[54]

At this point we should take at least a brief look at the portraits of the apostles. Typologically they are quite distinct from the image of Christ and are based instead on the traditional repertoire and iconography of the intellectual. Particularly characteristic are the conventional beard, the bald head, and the expression of concentrated thought. The countenance of Christ, by contrast, is free of any sign of exertion.[55] This is also true of Peter and Paul, who early on were set apart from the others in Roman art and received a distinctive physiognomy. Paul is usually bald and/or has a long beard tapering to a point, while Peter has a "classically" styled beard and hair.

Sometimes we may even have the impression that the assimilation of the apostles' iconography to that of the ancient philosophers may have served the artists or their patrons as a means of conveying certain specific messages. Thus, for example, on a well-known ivory pyxis in Berlin (fig. 165), the head of Paul is clearly reminiscent of Socrates, while Peter holds a "Cynic's club" and has the unkempt hair of an itinerant philosopher.[56] Both these visual allusions evoke earlier sets of associations.

Yet in spite of all these ties to the pagan iconography of the intellectual, the imagery of Christ quickly transcends the received tradition. Early Christian art brings about a fundamental change in the depiction of the intellectual and of the workings of the mind. For the first time we are confronted with a clearly defined hierarchy, in which the teacher enjoys absolute authority and the pupils appear fully devoted to him. Furthermore, for the first time the viewer is addressed directly and virtually drawn into the scene. The gathering of teacher and pupils becomes a kind of devotionary image. Not incidentally, from now on the book rolls and codices are displayed in such a way that the viewer is able to read the Holy Writ.

From the beginning there had been a growing tendency in scenes of Christ teaching to portray him as the dominant figure. Although some of the earliest catacomb paintings show Christ on virtually the same

Fig. 165

Ivory pyxis showing Christ enthroned as teacher above

the apostles, with Peter and Paul next to him. After A.D.

400. Berlin, Staatliche Museen.

scale as the disciples, he soon becomes larger and clearly elevated above them. Yet even so, the image of Christ as philosophical teacher was eventually not enough, since it failed to make visible his divine power. Thus from the late Constantinian period, certain elements of Imperial imagery were transferred to Christ, while court theologians and writers of panegyric developed a symbolic system to demonstrate how the power of the emperor is derived from that of God. On the sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, a youthful Christ appears enthroned on the arch of Heaven as kosmokrator, and it is not long before the apostles, imitating Byzantine court ritual, approach him with their hands cloaked, to receive the "law" from the hand of Christ. The viewer is invited to assume the same attitude of reverence. So, for example, on the sarcophagus of Bishop Concordius, two patron figures, representing the

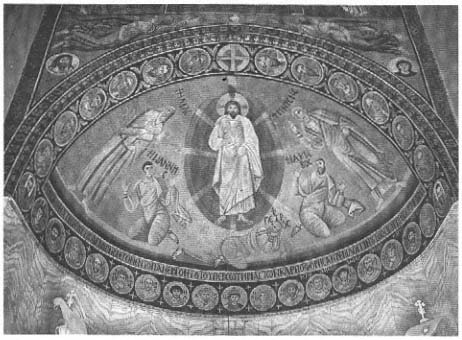

Fig. 166

Mosaic in St. Catherine's in Sinai, showing the transfiguration of Christ. Sixth

century A.D.

populace, are brought before the holy gathering in an appropriately humble pose (fig. 159).[57]

In these hierarchically structured compositions, the artists make good use of the different portrait types of Christ and the apostles in order to give added clarity to the relative ordering of status. Apart from Christ, only the prophets, the evangelists, and a few figures from the Old Testament who enjoyed positions of special authority, such as Abraham and Melchizedek, are depicted with long hair and a full beard. To differentiate them from Christ, they often have grey hair, or their hair and beard are not as carefully styled. Just how rigidly the hierarchy was sometimes observed is illustrated by the splendid mosaic of the transfiguration of Christ in the Monastery of St. Catherine in Sinai (fig. 166).[58] Christ hovers between Elijah and Moses, all three

represented in the portrait type of the "holy man." But whereas the two prophets stand on earth, Christ appears in a mandorla. Of the disciples at his feet and the apostles, saints, and true believers in the tondi, however, many are shown in the traditional iconography of the Greek intellectual.