The Past in the Present: Rituals of Remembrance

To summarize thus far, we have seen how the upper echelons of society were steadily taking on a new cultivated look. Whether they did this simply by the unthinking adoption of a newly fashionable beard and Zeitgesicht or consciously modeled themselves on specific prototypes, whether they looked this way in real life or only in their portraits, there can be no doubt that a man's image in society was defined using stereotypes from the onetime iconography of the intellectual. (The fact that such stereotypes functioned as such only subsequent to their creation made no difference.) The beard is the basic standard by which we can measure the progress of this process of transformation. The phenomenon had its origins in Athens, and it was there and in other cities of the Greek East that this masquerade went to the greatest extremes. But in the West too, in the course of the Antonine period, contemporary faces are gradually assimilated to those of the ubiquitous busts of an earlier age. How are we to understand this phenomenon? Or rather, is there really a phenomenon here at all?

First of all, I cannot stress enough that this was not simply a phenomenon of the visual arts but shaped the real world of daily life as well. The wearing of a beard and the cultivation of an intellectual image were by no means restricted to élite circles, a rarified social game

like playing at being shepherds in the age of the rococo. For the Romans, the setting was the public arena. As I have noted, there is no doubt but that the portraits and their costumes to some extent reflect the public identity and appearance of the subject. (Whether this reverence for high culture extended to walking the streets half-naked in midwinter as an exercise in asceticism one may well question.)

Nevertheless, we must understand the "learned beard" worn by so many men within its larger context. It is but one of many facets of the collective striving to evoke in the present the cultural achievements of the past. The notion of a "Renaissance" often used of this period carries the wrong connotations. It was not a matter of trying to bring back to life something long dead, but rather of claiming that this glorious past was not really past at all but lived on in the present. To support this claim, a whole series of cultural activities served to conjure up the past, and a broad cross section of society took part, some more actively than others. The scenario can be best observed in Athens and elsewhere in Greece.

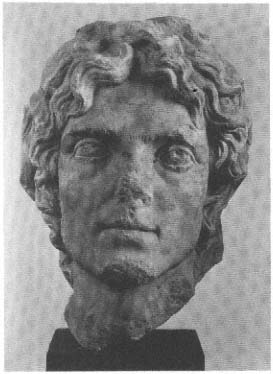

Fittschen has recently called attention to a group of portraits of youths and young men, mostly found in Greece, which, with their long flowing hair and heroic or elegiac expressions, often make a distinctly romantic impression (fig. 137).[63] Usually the portrait is combined with a nude bust, intended to recall Classical statues of heroes and athletes, as opposed to the "intellectual bust" partially draped in the himation. Fittschen has detected in this fashion an assimilation to Alexander the Great, and, indeed, some of the hairstyles are quite close to those of Alexander's portraits. But in the case of a number of these young men, who occasionally wear a short beard as well, identifying the source of the hairstyle in the portraiture of Alexander does not give the full story. For the contemporary viewer, the range of associations of these portraits must have been much broader. The variety of hairstyles worn by young men starting with Antinoos is particularly striking. I believe the long hair represents rather a general reference to the Classical image of the young hero. This does not, of course, rule out a specific reference in some instances to Alexander, whose own portraits are in turn closely linked to images of Achilles. Many ancient authors, from Homer on down, speak of Achilles' blond hair and the beautiful

Fig. 137

Portrait of a young Athenian in the guise of

the epic heroes. Antonine period. Athens,

National Museum.

long locks of other heroes. "From his head she made the thick locks descend like hyacinth," says Homer of Odysseus, when Athena has transformed him into a dazzling youth after his landing on the island of the Phaeacians (Od. 6.230). This and other comparable passages are cited by Dio of Prusa in his Encomium of Hair . Synesius of Cyrene found Dio's treatise so charming that he quoted parts of it in his own Praise of Baldness . Contemporary Roman viewers who were not so steeped in the poetic tradition would nevertheless have understood the connotations of long hair, thanks to the many mythological scenes in wall painting and on floor mosaics and carved sarcophagi.

And the romantic hero was not to be found only in the visual arts. At Marathon Herodes Atticus encountered a real-life Herakles, whom he invited home (he did not, however, accept). Herodes went hunting with his "sons" Achilles, Memnon, and Polydeukion. After their early deaths, he honored them like heroes, with funerary games and banquets, and erected stelai, herms, and altars to them on his vast estates. The Heroic Age of myth should carry on right into the present.[64] The story of Herodes is not a unique instance of the evocation of the mythical past, only unusual in its dimensions. Only recently there appeared on the art market a magnificent bust, probably from Greece, representing a young man as a new Diomedes.[65]

Women's fashions also started to look back at times more or less directly to Classical models, to judge from surviving statues and sculpture in relief. On the hundreds of preserved Attic gravestones of the Early Empire and later, the women are almost exclusively depicted in one of two Late Classical statue types, known in archaeological parlance as the "grande Herculanèse" and the "petite Herculanèse." It is hard to imagine that actual clothing, especially what was worn on festival days, could have looked very different. The men on the gravestones and in honorific statuary are also portrayed in a Classical costume that goes back to the fourth century. At least in the matter of clothing, the past truly did live on in the present. This phenomenon is not limited to Athens. Wherever in the Empire substantial numbers of honorary female statues have been found, they inevitably belong to one of a very few Classical or Hellenistic types. There are, of course, variations in individual preference, but the basic dependence on a relatively small number of models drawn from earlier Greek art remains unchanged through the first two centuries of our era.

The intellectual image was thus only one of several "costumes" that contemporary individuals could put on in order to turn themselves into "ancient Greeks" and, in so doing, demonstrate the unbroken continuity of classical culture.[66] In Athens and other Greek cities of long standing, at least the actors in this masquerade, these latter-day Sophists, heroes, philosophers, and romantic youths, had a genuinely ancient stage setting on which to appear. In many instances these

places now received a major face-lift: we need only think of Hadrian's great building program in Athens and especially of the Olympieion, after so many centuries and so many patrons now finally completed thanks to the emperor. These monuments of the past were real enough and encouraged people to believe that they were not simply living in a dream world.

Along with the costumes and the stage sets came a variety of retrospective rituals. We have already noted, in discussing the literary dilettantes and the public and private poetry readings of the Early Empire, how in general nonpolitical activities and neutral forms of exclusive social intercourse steadily grew under the Principate. By the time of Nero and the Flavians, it is clear that education and intellectual pursuits have become an important measure of social prominence. From the time of Hadrian, poetry is gradually displaced by such prose genres as learned rhetoric, along with philosophy. The curious phenomenon of the Second Sophistic, some of whose elements may be off-putting to us today—the fixation on themes from the distant past, the rhetoricians' spectacular feats of memory, the pedantic straining to achieve the purest Attic dialect with the most arcane expressions—all this can be understood only within the context of an entire society struggling to revive the memories of the past. The formal speeches held at the great city festivals and Panhellenic games are also part of these rituals of remembrance, elements of an all-encompassing discourse in both the public and private spheres that provided the Romans with a communal assurance of the continuity and living presence of the past.

No less than in public, the private sphere and various forms of daily social interaction were characterized by the backward-looking rituals of the cult of learning. Perhaps the most revealing of these is the practice of learned conversation at the symposium. The handy compendia of classical culture contained in the Attic Nights of Aulus Gellius and the fifteen volumes of Athenaeus' Deipnosophistai, and even earlier in the nine books of Plutarch's Conversations at Table (Quaestiones conviviales ), offer a wide spectrum of useful knowledge of all kinds, organized thematically: mythical and historical, literary and philological, scientific and philosophical, antiquarian, abstruse, and fantastic. From these

works we gain an authentic (and also idealized) picture of the topics, views, and arguments that were likely to come up in learned conversation after a meal. As in the rhetorical showpieces delivered in public, here too in these evening conversations a good memory and mental alertness were all-important. But the strenuous effort required was mitigated by the fact that no one expected originality. Rather, intellectual prowess could be demonstrated time and again by calling up the same topics, the same exempla drawn from myth and history. As odd as this sounds to us, it is not so long ago that it was still common practice in Europe to prepare in advance for a dinner party. In some places the topics of conversation planned for the evening were indicated on the invitation so that one could prepare with the help of such conversation manuals as Isaac d'Israeli's Curiosities .[67] At the ancient dinner table, whatever the subject, whether hetairai or philosophers, culinary delicacies or the intricacies of prose style, the examples cited always came from the distant past, the paradigms from the world of myth, and any advice or precedent was centuries old. In short, this was an age of, as it were, living classicism, which shaped much of both art and life.

The most celebrated intellectuals were competing for more than just public recognition. Glen Bowersock has shown how they often came to rank among the leading citizens of their respective cities and led the political and cultural rivalry with other cities, as well as competing among themselves for the favor of the emperor, who would award them higher and higher public office.[68] The emperors themselves even fell under the sway of this cult of the intellect and its high priests. The leading Sophists became their closest advisers and friends, oversaw the Greek bureaucracy, and educated the imperial children. The emperors were not just observers and patrons of this cult but took an active part in it, whether it be the romanticized pederasty of Hadrian or the introverted meditations and philosophical exercises of Marcus Aurelius, composed in Greek.

While for the élite education and intellectual prowess were an avenue to success in the competition for status and influence, for broad strata of the prosperous bourgeoisie these inevitably became tokens of social acceptability. The numbers of those actively involved in the general craze for learned pursuits, like the amateur poets, seem to have

Fig. 138

Sarcophagus of the youth Marcus Cornelius, with scenes from

his childhood, from Ostia. Ca. A.D. 150. Paris, Louvre.

rapidly increased. This is seen most impressively in the mythological imagery so popular on sarcophagi starting in the time of Hadrian. The Classical imagery employed becomes a form of dazzling and recherché funerary rhetoric, mourning the deceased and celebrating his or her virtues by means of sometimes rather abstruse allegories and mythological parallels.[69] These learned images become much more than mere ornament and directly involve both patron and viewer, since the scenes echo their own situation (e.g., as mourners) or delineate a set of shared ideals. In this way even private experience was expressed through learned parallels, and the ordinary viewer felt drawn into the discourse of high culture as an active participant.

Nor was the daily life of the bourgeoisie unaffected by this phenomenon. On a child's sarcophagus of about A.D. 150, the life of a boy who died young is portrayed (fig. 138).[70] We glimpse the interior of a bourgeois household, with the mother herself quieting an infant. The father, standing nearby, also partakes of the shared familial bliss, but in a curiously distanced and intellectualized manner. He stands in the pose of the Muse Polyhymnia, leaning against a pillar and lost in meditation, a book roll in his hand testifying to his intellectual interests: a professor in the playroom!

On the other side of the scene he personally instructs his now adolescent son. This is a marked departure from both the conventional iconography and the actual circumstances of the age, at least in more

prosperous families. Later sarcophagi with such scenes of reading invariably feature a Greek teacher in this role. While the father here wears a toga, the professional tutors are depicted wearing only a himation over a bare torso, to indicate their strict adherence to the philosophical life. Yet this father is otherwise shown like a philosopher, in his contemplative pose.

The way he holds the child in his arm, again wearing a proper toga, is also without parallel. It would seem that in this instance the patron had a direct influence in determining the imagery and that he wanted to project simultaneously a cultivated life-style and the ancient ideal of the Roman paterfamilias, like the elder Cato. It was said that Cato liked to watch as his wife quieted their small son and, "later on, himself instructed the boy in reading and writing, even though his slave Chilon was an accomplished teacher of grammar" (Plut. Cat. Mai. 20.4). At the same time, the patron of our sarcophagus could have been influenced by a contemporary Stoic philosopher from the school of Favorinus, who insisted that even a woman of distinction should cradle her own child, since this was the way of nature (Gell. 12.1). This modest sarcophagus shows how intellectual pretensions were by now almost taken for granted among the middle class, and how they were entirely compatible with a sense of nostalgia for the proud traditions of Rome's past.[71]

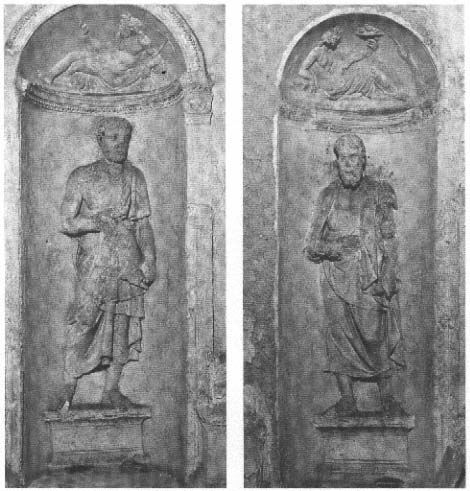

The claim to universal learning is made much more spectacularly in the richly decorated funerary chamber of the freedman C. Valerius Hermia in the cemetery underneath St. Peter's. On the principal wall of the chamber stand five stuccoed statues in relief, the three in the middle representing patron deities of the family, including Hermes for prosperity (as well as being Hermia's "namesake") and Athena for education. To either side of these three, however, stand figures of intellectuals (fig. 139). Since both figures bear different portrait features, and the patron himself is shown with his family on the left-hand wall, it seems likely that these are the teachers of the deceased who are so honored. The upwardly mobile former slave evidently shared the ideals of his emperor, Marcus Aurelius, and was as grateful to his teachers as Marcus, who set up their golden imagines alongside the Lares in his domestic shrine (Hist. Aug. , M. Aurelius 3.5). The two intellectuals

Fig. 139

Philosopher and rhetorician, probably the teachers of Gaius Valerius. Stucco reliefs

from the tomb of the Valerii in the necropolis under St. Peter's. Ca A.D. 170.

on Hermia's monument. it should be noted, are clearly distinguished from one another in manner and appearance. The elder, on the right-hand side, is easily recognized as a philosopher by his long and unkempt hair. The other is most likely the teacher of rhetoric, judging by his carefully draped garment and elegant coiffure.[72]

When a freedman like Hermia honors an ascetic philosopher as his mentor, then we are justified in thinking that the general attitude in Rome toward philosophy has decidedly changed for the better since the days of Trimalchio. To be sure, people's expectations of philosophy had also radically changed. No more contentious debates, abstruse definitions, or scientifically argued theses—in short, all the things the Romans had earlier made fun of. Instead, philosophy was now called on, first and foremost, as a guide to living one's life.

This had, of course, always been the role of the house philosopher. When Livia lost her son Drusus, she asked for philosophum viri sui (Sen. Dial. 6.4). This casual comment shows that philosophy's role as consolation was already well established at this time. Subsequently, however, people turned to philosophy not only for learned conversation or in moments of great need, but as a fundamental guide to life.

It was their growing "care of the self" that brought people under the Empire to philosophy and to the philosophers (as well as to mystery religions and others promising salvation). Neither the state religion nor the imperial cult could offer anything here, but a strict mental and physical regimen might. Physician and philosopher joined forces, for both taught the principles and standards of behavior, and both counseled their "patients" with advice, admonitions, and chastisement. The onetime scholar and learned partner in conversation became during the Empire a spiritual counselor, to whom people entrusted their well-being. As a result, the authority of the philosopher gradually increased once again, but it was now of a very different kind.