The Elegant Intellectual

The leading orators of the day were the exact opposite of the philosophers in their public image. They wore extravagant clothing, reeked of precious scent, and expended enormous effort on the care of both hair and body. Alexander of Seleucia, for example, whom some considered the son of Apollonius of Tyana, possessed a beauty that was like a "divine epiphany" (if we may believe Philostratus). The Athenians were intoxicated "by the splendor of his large eyes, the lush locks of his beard, the perfect line of his nose, his white teeth, and long slender fingers," even before he opened his mouth to speak (VA 2.5.570–71). And yet their contemporaries also attacked the Sophists, whose luxurious ways they so admired, for their greed. This, too, of course, is a classicizing topos. The public appearances of these superstars who elicited such admiration were by no means limited to speech making. Polemon of Laodicea in Asia Minor (ca. A.D. 88–144), one of the most brilliant "concert speakers" of his day, traveled with "a long train of pack animals, many horses, slaves and dogs of various breeds for different types of hunting. But he himself traveled in a Phrygian or Celtic wagon with silver trappings" (Philostr. VS 25.533). His own arrogance was a match for his appearance.

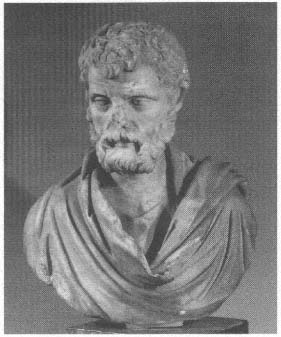

We would expect to find portraits of such men marked by a striking elegance and fashionable touches. Yet unlike the images of ascetic philosophers, those of the elegant Sophists cannot with certainty be identified among the plethora of preserved portraiture of the Antonine and Severan periods. If we take the portrait of Herodes Atticus as our standard (fig. 134), it is not all that different from those of other kosmetai derived from Late Classical models.[58] The same is true of the portrait of a rhetorician and benefactor of the city of Ephesus in Severan times whose identity is unfortunately unknown to us. The portrait stood in the imperial hall of the gymnasium of Vedius and reveals itself as that of an orator through its Aeschines-like pose.[59]

But this is not really so surprising, since these Classical faces sufficed to express the intellectual pretensions of the orator. In addition, they can hardly have wanted their public portraits to fuel even more the charges of luxuria constantly being made against them. On the con-

Fig. 134

Bust of the rhetorician and statesman Herodes

Atticus (ca. 101–177). Paris, Louvre.

trary, we may suppose that most of them wished to combine their man-of-the-world elegance with a hint of philosophical seriousness, though not going as far as to give an impression of the severity of the Cynics or the toughness of the Stoics.

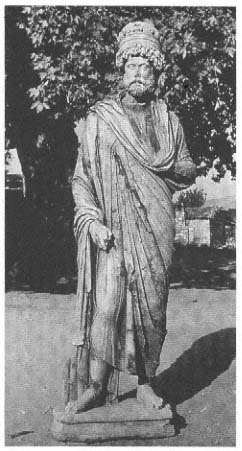

Apart from Herodes Atticus there are, unfortunately, no securely identified portraits of the celebrity orators. Yet a statue like that of L. Antonius Claudius Dometinus Diogenes, the patron and "lawgiver" of Aphrodisias, "father and grandfather of Roman senators," may give some idea of the splendid public image of such men. (fig. 135).[60] As a sign of his priestly office he wears a diadem adorned with portraits of the city goddess and the imperial family. The case with many book rolls alludes to his learning, while the epithet Diogenes expresses his genuine commitment to the philosophical life. This has not stopped

Fig. 135

Portrait statue of Lucius Antonius Claudius

Dometinus Diogenes, from the "Odeon" at Aphrodisias.

Early third century A.D. Aphrodisias, Museum.

him, however, from sporting an elaborate coiffure that could hold its own against that of a Lucius Verus.

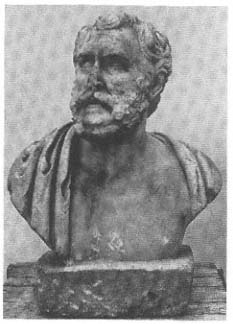

Other portraits of this period, such as those of two magistrates from Smyrna, now in Brussels, are remarkable for their elegantly styled beards and yet wear their hair closely trimmed, like Theon the Plato-

Fig. 136

Bust of the great orator Polemon (ca. 90–145),

Athens, National Museum.

nist. In his case, we took this Stoic trait as a subtle suggestion of a philosophical seriousness.[61] Anton Hekler made the attractive, but entirely hypothetical, suggestion that a bust found in the Olympieion at Athens represents the above-mentioned Polemon of Laodicea (fig. 136). It was he who, in A.D. 131 in the presence of the emperor Hadrian, delivered the dedication speech for the Olympieion. He spoke passionately and, in the Asiatic baroque tradition of oratory, did not shy away from such dramatic effects as leaping up from his throne. The portrait's dramatic turn of the head and the mannered gaze, unique in the portraiture of the Roman Empire, would well suit such an occasion, particularly since it is reported of Polemon that throughout the speech he kept his gaze fixed on a single spot.[62]

The search for a specific portrait type for the Sophists seems to lead

to a dead end. For the time being, at least, we cannot detect one with certainty among the preserved material. And yet the examples we have just considered show that, alongside the portraits of amateur intellectuals with Classical faces and the unkempt hair of the true ascetic, there were others with an elegantly soigné appearance steeped in luxury. It seems unlikely in these instances that the bare chest under a philosopher's mantle should be taken literally, with its original connotation of the toughening of the body through physical deprivation, as in the statues of Chrysippus and other Hellenistic philosophers. As we have seen, busts of this type are quite common starting in the Hadrianic period. Rather, this feature has probably become simply a formula signifying Greek-style paideia .