Humble Poets and Rich Dilettantes

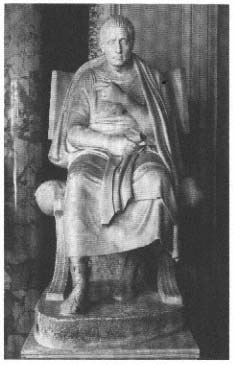

Against this background, two statues in the Vatican, which we considered earlier in discussing Hellenistic portrait statues of poets, take on an added significance as evidence of the Roman preoccupation with otium (fig. 110). As we have noted, sometime after the middle of the first century B.C. the heads of the Greek poets were reworked into portraits of contemporary Roman aristocrats.[19] That the patrons were indeed members of the senatorial aristocracy is revealed by their shoes. The indication of the calceii senatorii is indisputable proof of their social rank. Thus cultural pretensions and pride in one's social status go hand in hand. The provenance suggests they originally stood in the garden of a city residence on the Viminal Hill, that is, that they served to dis-

Fig. 110

Statue of the Hellenistic comic poet Poseidippus. The

portrait head was reworked into that of a Roman senator

after ca. 50 B.C. Cf. fig. 75. Rome, Vatican Museums.

play the patrons' cultivated image within the private sphere. The claims they make were directed at invited guests of comparable status. This case is typical of the whole phenomenon. Portraits of famous Greeks were so pervasive in their influence that by the first century B.C. the Romans could express their own intellectual aspirations only by allusion, assimilation, or by actual appropriation, as in this instance. Such statues blatantly transform the would-be intellectual's habit of affecting Greek dress, about which we have already heard, into a permanent image.[20]

It is no accident that these two Romans had themselves depicted

not as philosophers, but as poets. In the Roman imagination, the cultivation of Greek literature was desirable, but only as a means for perfecting one's skills in public speaking or one's style in the writing of history. The pursuit of philosophy especially when taken too seriously or for its own sake, remained suspect well into the High Empire—even though more than a few Roman aristocrats did indeed practice serious philosophy from the first century B.C. on. The writing of poetry, on the other hand, early on enjoyed recognition in society. Ennius was already frequenting the houses of the aristocracy, and Angustus would later accord public honors to his favorite patriotic poets. Yet the professional poets at Rome, even the greatest among them, were not autonomous and remained dependent on a patronus .[21]

This is all the more remarkable when we consider that literary dilettantism was virtually epidemic in Rome by the time of Augustus and involved the entire aristocracy, including the imperial family. (Nero's artistic career and public appearances performing his own compositions may be counted here as well.) In his Darstellungen aus der Sittengeschichte Roms of 1922, Ludwig Friedländer already recognized the cultural significance of this dilettantism and the cottage industries associated with it. He also pointed out the connection between the old aristocracy's loss of political influence and its new preoccupation with amateur versifying. This is not the place for a detailed account of the various forms taken by such literary games. Suffice it to say that the combination of a plethora of public and private poetry readings, performances of song and dance, poetry festivals and competitions instituted by Nero and Domitian, with the expansion of both public libraries and the book trade gradually created something of a "literary public." The dimensions and spread of this self-propelling literary juggernaut seem to have been tremendous. The volume of invitations that were not to be declined must have quickly become too great, even for someone like Pliny the Younger, who himself wrote and recited poetry.[22]

Along with the culture of otium, this passion for literature, beginning in the time of Augustus, represented another important step toward the "cult of learning." In both instances, one was transported through literary and other pastimes into a world of high culture far

Fig. 111

Portrait of a woman composing verse. Fresco from

Pompeii, ca. A.D. 50. Naples, Museo Nazionale.

removed from the reality of life. The poetry itself was predominantly on apolitical themes, cloaked in a veil of allegory and mythological allusion. The intellectual culture of otium spread out from the villas and to some extent took over public life as well. Not only recitations of poetry, but also theatrical performances and pantomime, seduced the audience into a world of myth. Juvenal ironically condemns the resulting loss of any sense of reality: "No one knows his own house as well as I know the grove of Mars, the cave of Vulcan, and the Aeolian rock" (1.7ff.).

These literary pastimes were not limited to the city of Rome, as one might suppose from the written record alone. I would argue that they are also reflected in the many small-scale wall paintings in the houses of Pompeii showing writing utensils along with readers and writers, images that have never been satisfactorily explained. On a well-known portrait tondo (fig. 111), a young woman with Claudian coiffure looks out at the viewer while pressing a stylus to her lip in a gesture of distracted contemplation. The little tablets in her hand also allude to her

interest in writing. This distinguished woman, adorned with earrings and a golden hair net, is surely not a writer by profession, nor would she need to demonstrate that she is able to write. Probably she is the mistress of the house, or one of the daughters, shown composing poetry. Another equally famous tondo depicts a young married couple. Once again the woman holds writing utensils, but her husband is also characterized as an educated man by the prominently displayed book roll. Similar portrait tondi have been found in several other Pompeian houses. Some of these show a youth with book roll and a laurel wreath in his hair, a reference perhaps to actual or anticipated victories in poetic competitions. The tondo form suggests that the bourgeoisie adopted this newly fashionable manner of having themselves portrayed from the public libraries, which we know displayed portraits of poets. It is also striking that those shown as poets are almost invariably women or youths. In the private world of otium, women were equally admired for their literary pursuits. It is unlikely that the citizens of the once Oscan city of Pompeii were any more passionate about learning than those of other Italian cities. Rather, these small pictures attest to an astonishingly pervasive enthusiasm for the reading and writing of poetry throughout the Italic world.[23]

The flowering of this extraordinary preoccupation with learning must have enhanced the self-esteem of the professional poet, even if his material circumstances, as the example of Martial indicates, had in fact worsened between the time of Augustus and the end of the first century. He remained dependent on the favor of a patron, compelled to celebrate his patron's villa or wife or taste in the fine arts.

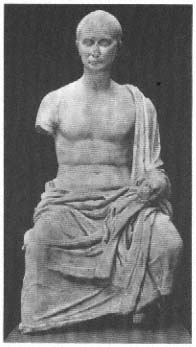

A seated statue from Rome, now in the Albright Art Gallery in Buffalo, somewhat under life-size, presents a poet in a mood of remarkable, if rather strained, self-assurance (fig. 112). We recognize him as a poet by the book roll and Greek manner and clothing, a mantle that leaves the entire torso exposed. The models for this figure are not the earlier Greek statues of poets, in their citizen dress and relaxed pose, like Menander and Poseidippus, but rather the exaggerated heroic imagery of Late Hellenistic art that we saw exemplified in reliefs of Menander (fig. 74). The pose is here even more exalted. The poet sits straight as an arrow, with his legs apart, not unlike the type of Jupiter that inspired images of the enthroned emperor. The sculptor of a sec-

Fig. 112

Funerary statue of an Augustan poet,

from Rome. Buffalo, Albright Art Gallery.

ond statue of a poet in similar pose, Trajanic in date and now in the Terme, added the realistic features of advancing age to the bare torso, thus creating a link to the iconography of the philosopher. Both statues probably stood in grave precincts and represent professional poets. A member of the aristocracy could hardly have had himself so depicted, with none of the attributes of his social status. Furthermore, the statue in Buffalo was hollowed out inside, probably to contain the ashes of the deceased. It will most likely have stood in the funerary precinct of the patron, who may also have paid for this statue of his in-house poet.[24]

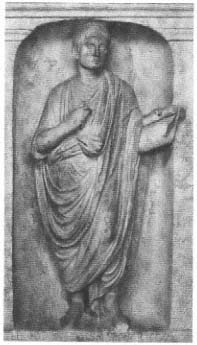

Whereas in these statues the use of allusion to Greek tradition to proclaim a particular virtue is somewhat heavy-handed, the parents of an aspiring and gifted poet who died in his youth, named Sulpicius

Fig. 113

Portrait of the boy poet Q. Sulpicius Maximus.

Detail from his funerary monument, ca. A.D. 94.

Rome, Palazzo dei Conservatori.

Maximus, had their son depicted as the proper Roman citizen, in a toga (fig. 113). He had competed against fifty-two Greek-speaking rivals in a poetry contest sponsored by the emperor Domitian. The proud and devastated parents spared no expense, including having the entire Greek poem that he recited inscribed on the gravestone. Interestingly, the poem portrays Zeus denouncing Helios for entrusting the chariot of the sun to the young Phaethon. It was too much for the poor boy, like Sulpicius Maximus himself, who died of exhaustion "because day and night he thought of nothing but the Muses."[25]

It seems as if the contemporary poet in the early Empire had a choice between only two radically different images with which he could identify: a seated statue in the Greek manner (but with the stan-

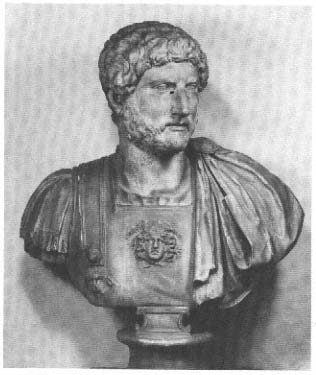

Fig. 114

Cuirassed bust of the emperor Hadrian. After A.D. 117. Rome,

Palazzo dei Conservatori.

dard Zeitgesicht derived from the current fashion of the imperial house) or the basic type of the Roman citizen.