The Retrospective Philosopher Portrait: Socrates, Antisthenes, and Diogenes

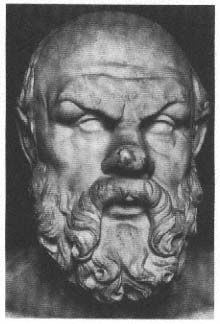

Another, even more particular function of the retrospective portrait can be inferred from some of the philosopher statues. A Middle or Late Hellenistic Socrates is perhaps the most fascinating of the new interpretations of older philosopher portraits (fig. 92).[28] The artist incorporates elements of both fourth-century portrait types (cf. figs. 21, 35) but creates a new interpretation of the silen's mask. It is for him no longer a metaphor for wisdom, but simply a formula to express extreme ugliness. This new Socrates also has a hideously broad and unattractively shaped nose, a completely bald pate, and sunken cheeks, all of which bespeak an individualized physiognomy. Yet at the same time he is characterized as a mighty thinker in the powerfully arching cranium.

The combination of the dramatically tensed brow and the dignified locks of the archaizing beard with the ugly little pug nose has an almost comic effect for the modern viewer. Socrates has been turned into an intellectual pioneer in the Stoic mold, recalling the mighty strain in the face of a Zeno or Chrysippus (figs. 53, 55). One might easily imagine the commission for this image coming from a Stoic school that wanted to honor its spiritual ancestor with a monument that captured

Fig. 92

Socrates. Roman copy of a Hellenistic

statue. Rome, Villa Albani.

his mental powers in a compelling and contemporary fashion, unlike the Classical portrait type. This vision would of course have been completed with an appropriate body, most likely seated in a vigorous pose of cogitating or instructing. There are several types of seated figures of Socrates that survive in various media, but unfortunately none can be associated with certainty with the type of the portrait head in the Villa Albani.[29]

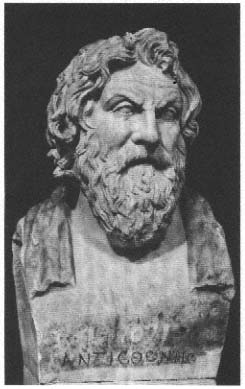

A similar situation might obtain for the impressive portrait of Socrates' pupil Antisthenes, who was revered as a spiritual ancestor by both Cynics and Stoics (fig. 93). The dating of the portrait type, which is preserved in an inscribed herm copy, has been an unusually thorny problem for scholars.[30] The basic iconographical type is that of the

Fig. 93

Antisthenes (ca. 450–370). Herm copy of a

Hellenistic portrait. Rome, Vatican Museums.

Classical old man of fourth-century grave stelai, with long and sometimes disorderly hair, but here combined with a dramatically rendered brow of the deep thinker, an element that does not occur in Classical portraits. There are physiognomic traits as well, which seem to be linked to the character and intellectual qualities of this particular thinker. All this suggests that the type belongs to that of the retrospective portraits, which in turn supports a dating first suggested long ago, in the early second century B.C.

A clue to the interpretation of the head is suggested by the striking

contrast between the carefully tended beard and the vigorous movement of the long and uncombed hair, something unique to this head among philosopher portraits. The contrast seems to be deliberate, and beard and hair may not necessarily convey the same message. The locks rising from above the forehead had been a popular symbol of strength and energy ever since the portraits of Alexander the Great; and centaurs, silens, and giants were all characterized as "wild" creatures by a similar treatment of the hair. It is tempting to see here a reference, again recalling the bioi, to Antisthenes' vigorous and abrasively contentious character or to his much-admired moral rigor. We may even remember how the chauvinistic Athenians never forgot Antisthenes' half-barbarian origins as the son of a Thracian mother. It is quite conceivable that such a reference could be intended in a biographical portrait of this type; Diogenes Laertius' biography, at least, begins with a mention of this circumstance of the philosopher's birth.

The vigorous movement of the forehead, the eyebrows raised with an almost ferocious intensity, proclaim the intellectual energy of this toothless old man. The well-tended beard, on the other hand, may be interpreted simply as a classical "philosopher's beard," if the second-century date is correct. That is, the beard was meant to label him as "one of the philosophers of old." This handsome and old-fashioned beard balances the individualized characterization embodied in the widly unkempt hair and underlines the seriousness of Antisthenes' philosophy, irrespective of his "character." The pose of the head and the bunching of the drapery at the back of the neck suggest a seated statue. He was evidently depicted as a teacher, unlike the Cynic in the Capitoline (fig. 72). Nor does Antisthenes betray any other Cynic features, and the portrait was surely not conceived as that of the founder of this philosophical "sect." We could, however, imagine a Stoic context for this portrait, as for the Hellenistic Socrates.[31]

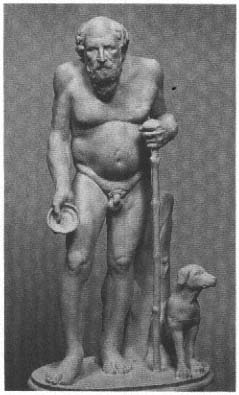

The well-known statuette of Diogenes may also be best interpreted within the framework of specific biographical and philosophical/didactic interests (fig. 94).[32] The completely naked body is unique in the iconography of Greek philosophers and might lead one to wonder if this could be an innovation of the Imperial period, reflecting the

Fig. 94

Diogenes (414–323). Statuette of the Imperial

period after a Hellenistic original. H: 54.6 cm.

Rome, Villa Albani. (Cast.)

popular mockery of the philosopher or an interest in the purely anecdotal. On the other hand, the keenly observed realism, especially in the startlingly misshapen and ugly body, is in the direct tradition of works of the third century B.C.

A tired old man, he walks slowly, bent over a staff that he holds in his left hand. The right hand was probably outstretched and might well have made a gesture of begging, as in the eighteenth-century restoration. The body is stiff and ungainly; neither standing still nor moving is easy for the old man. The sagging belly shows that this old man, who

had nothing but contempt for exercise and training in the gymnasium, never did anything to stave off the outward signs of aging. Yet his begging managed to keep him well fed, and the contrast with, say, the emaciated "Old Fisherman" (fig. 61) is obvious. Though these traits could be taken in the anecdotal spirit of later Roman mockery of the intellectual, the impressive bald head of the philosopher, the thoughtful expression, and long, dignified beard (best preserved in the copy in Aix-en-Provence) nevertheless suggest that this Diogenes and his teachings are to be taken seriously. This is surely not the kind of head one would have expected to go with this body, but the sculptor knew what he was doing in this striking contrast.

Once again the ruthless depiction of a decrepit body must be understood in the context of contemporary negatively charged imagery of fishermen and peasants. But, as in the case of the supposed Cynic in the Capitoline (fig. 72) and the Pseudo-Seneca, our reaction is meant to be one of admiration. Diogenes taught his pupils to despise societal convention, including the care of the body, and to renounce all material possessions as a prerequisite to a true independence and spiritual freedom. The naked body is evidently meant to express visually the uncompromising way of life and defiant protest of the founder of the Cynics, truly philosophy in action.

Whereas the realistic appearance of the Cynic in the Capitoline reminds the viewer of the appalling and irritating public behavior of such men and thus presupposes one's experience of them, Diogenes' nudity has a very different significance. Even though the depiction of the body is highly realistic, the figure does not represent an actual encounter. The artist is not striving for the directly provocative effect of the Capitoline Cynic. Even the Cynics did not really walk naked through the streets but wore the tribon made of coarse material (D. L. 6.22). The nudity has rather a didactic meaning and embodies a moral challenge. The sculptor assumes a familiarity with Cynic writings on the part of the viewer, and the statue calls these teachings to mind and "preaches" them, as Diogenes himself once did by means of his appearance: freedom from want and contempt for the body, for physical beauty and bourgeois conventions. Our encounter with the naked Diogenes is, as it were, literary; it takes place not in public, but at home or in

the philosophical school, which is to say in our head. When later Roman writers speak of the nudi cynici (Juv. 14.309; Sen. Ben. 5.4.3), they have in mind just such a portrait.

The iconography of the head, on the other hand, stands in the tradition of Late Classical portrait types, as does that of Antisthenes. Some scholars have even thought they detected similarities to the portrait of Socrates, which escape me.[33] We may once again suspect that the commission for the original came from the Hellenistic Stoics, who are known to have been the first to collect anecdotes about Diogenes.

In spite of his promotion to the status of a serious philosopher, this Diogenes has nothing to do with the popular hero of the Enlightenment, going about with his lantern and searching for the truth, literally bringing it into the light. The Diogenes of this statuette remains purely a figure of dissent. He has no program to offer and no interest in "progress." At most he stands at the threshold of a philosophical school, by exhorting the viewer to contemplation and exposing the superficiality and "unnaturalness" of conventional life-styles through his own unorthodox behavior. When we find him again, on simple gravestones of the Early Empire, reclining in his cask, he has become nothing more than a memento mori, a symbol of contempt for the world, since death is inescapable.[34]

As we have seen, the retrospective portraits of intellectual heroes of the past arose out of a particular need: they functioned as icons in a unique cult of paideia, even to the point of being actual cult statues in hero shrines. Gradually it seemed the whole of society in urban centers was reading and interpreting the great writers of the past, scholars and orators as well as poets and philosophers. In an age when the structure of individual identity was changing and the inexorable power of Rome loomed on the horizon, these portraits were for the Greeks the principal guardians of their cultural identity. One could see them as a kind of exercise in collective memory in the quest for stability and proper orientation in life. The new cult manifested itself not only in the heroa, but in many branches of education that took in a whole spectrum of both private and collective forms of veneration of the poets and philosophers of the past.[35] Alongside public lectures and

poetic and musical competitions in the gymnasia, there is evidence from the private sphere as well. The appearance of images of the poets and illustrations from their work from the first century on, not only on gemstones and silver vessels, but also on the painted walls of Delian houses and even on humble terra-cotta bowls, gives some idea of the ubiquitous presence of this literary culture in the cultivated home.[36] A good example of this is a silver cup from Herculaneum, probably of Augustan date but employing an earlier motif. The scene is the apotheosis of Homer. The poet is carried aloft by a mighty eagle (as Roman emperors later will be). On either side sit female personifications of the Iliad and Odyssey , who assume a remarkable pose, lost in contemplation, that anticipates the proper attitude of the educated reader.[37]

The attitude toward the intellectual giants of the past is now marked by pious meditation, reverence, and the distance inspired by great awe, in contrast to the public monuments honoring the tragedians in Lycurgan Athens. These new images are bold visions, freed from the bourgeois conventions of contemporary life and retrojected onto an idealized past. At first glance the situation may seem to parallel the glorification of the intellectual hero by the educated bourgeoisie of the late nineteenth century (cf. pp. 6ff.). But Hellenistic readers and devotees were different in genuinely and quite actively seeking guidance for their own lives in the writers of the past. Culture was not some ideal world relegated to a few leisure hours spared from the "real world" of commerce and social interaction. Rather it was the focal point of life as it was lived and the foundation of both personal and collective identity.