The Late Antique Philosopher "Look"

The image of Christ as the teacher of wisdom was not simply derived from that of the theios aner; it was in some sense in competition with it. It is, unfortunately, not possible to reconstruct this process of mutual influence in detail, since the body of evidence for Late Antique philosophers is tiny compared with the wealth of representations of Christ and is mostly quite late as well. There are, however, some literary descriptions that present an impressive glimpse into the beliefs and concerns of the philosophers. They show that their mentality was in many respects not so very different from that of contemporary Christians.

Starting in the third century, the popular notion of a philosopher and what was expected of him once again underwent a major change. Eunapius' Lives of contemporary "philosophers and Sophists," written about 400, are fundamentally different from Diogenes Laertius' Lives of the Philosophers or the Lives of the Sophists of Philostratus, both works of the early third century. While both these earlier accounts deal with men who were well integrated into urban society and displayed a whole range of human strengths and weaknesses, Eunapius writes what are basically hagiographies. He presents the reader with a new kind of mental and spiritual superman who despises his mortal body and continually seeks purification in order to be nearer the gods, who even enjoys certain divine powers himself, and whose entire life is surrounded by an aura of the mystic and the sacred. Each one of the Lives is based upon the same catalogue of physical and spiritual qualities that we first met in Pliny's description of Euphrates. But in addition there is a greatly heightened religious dimension to them, manifested in supernatural phenomena, miracles, and prophecies that attest to the

presence of the divine in these men, "priests of the all-encompassing divinity" (Porph. Abst. 2.49). Here, for example, is Eunapius' description of the philosopher Prohairesios: "One could scarcely estimate his size, so much did he exceed all expectation. For he seemed to be nine feet tall, so that he looked like a colossus, even when he stood along-side the tallest of his contemporaries" (VS 487). When Prohairesios was summoned to Gaul by the emperor Constans, many "could not really follow his lectures and thus admire the secrets of his soul. For this reason they clung to what they could see clearly before them, the size and beauty of his body. They looked up to him as to a colossal statue, so much did his appearance outmeasure any human standard" (VS 487, 492).[59] The religious aura is intensified by the repeated references to looking up to a statue. As early as the mid-third century, in a scene from the tomb of the Aurelii in Rome, is a depiction of one of the miraculous wise men, over-life-size, sitting in some public place and instructing the throngs who crowd around him.[60] We are apparently dealing here with a very widespread need, among Christians and non-Christians, educated and uneducated people alike, to believe in an incarnation of the divine, and even the "holy men" themselves could not escape it. Iamblichus, for example, feels compelled to contradict his pupils when they believe that when he is privately at prayer, "his body would rise up ten ells above the earth, and his garment would radiate with a golden beauty" (Eunap. VS 458). When the transfigured Christ appears in the mandorla, he embodies essentially the same visual conception.

With all this, the great philosophers of late antiquity still considered themselves the spiritual heirs to the classical tradition. They sought their philosophical roots above all in certain of the metaphysical writings of Plato, which they had "rediscovered" and "purified." In their daily lives, however, they modeled themselves most closely on Pythagoras, the ascetic, pious, and pure philosopher of Porphyrius' description ( Vit. Pyth. ). Indeed, Philostratus had already turned Apollonius of Tyana into a pure Pythagorean. Starting with Plotinus, this amalgam of Platonic, Pythagorean, and mystical elements was thought to constitute a sacred teaching, which would be passed on within the Neoplatonic school from generation to generation, by one "divine"

(theios ) or "holy" (hieros ) man to the next. Unlike in earlier philosophical schools, contemplation of the divine, oracles, and secret teachings all now played a central role. In the practice of what is called theurgy, associated above all with Iamblichus, the gods themselves intervene directly and raise up the human soul to themselves in a gesture that transcends anv intellectual effort.[61]

But not every worshipper had equal access to this ultimate mystery. The result was a new set of hierarchical structures within the philosophical schools, very different from that of Christianity. The fundamental distinction was between, on the one hand, the traditionally learned philosophers, known as philosophoi or philomatheis ("lovers of learning") and, on the other, those few who had attained the highest form of mystic revelation, the hieratikoi, theioi, or hieroi .[62] These "divine" individuals were above any criticism. Eunapius describes the effect that Maximus of Ephesus, the controversial teacher of Julian the Apostate, had on his pupils: "No one dared contradict him, even the most experienced and verbally skilled of his pupils, on those rare occasions when they dared address him at all. Rather, they listened to him in rapt silence and took in everything he said, as if it had been spoken from the tripod [of Apollo in Delphi]. So sweet and compelling were the words that issued from his lips" (VS 473).

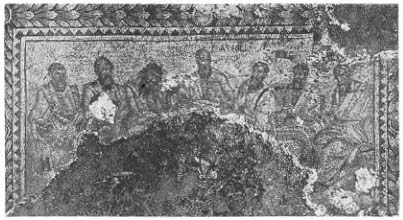

This spirit of subservience to a towering figure of intellectual authority is already reflected on a beautiful philosopher mosaic in Apamea made after ca. 350 (fig. 167). Six of the ancient sages sit on either side of Socrates and listen to his teachings. Although they are still characterized by physiognomic differences, it is only Socrates, elevated like Christ by his central position, who is named by a large inscription. The very man who once cast doubt on the idea of certain knowledge now instructs others ex cathedra . The mosaic was found at Apamea in Syria, the home of a famous Neoplatonic school where Plotinus' pupil Iamblichus, one of the "golden chain of the divine," had taught.[63]

After the triumph of Christianity, the philosophers and rhetoricians lost the tremendous prestige that they had earlier enjoyed in Roman society. Although their ranks continued to be replenished from the urban aristocracies, and they occasionally still held public office, after the failure of Julian the Apostate they quickly became marginalized.

Fig. 167

Mosaic in Apamea in Syria, showing Socrates as the teacher of

philosophers and wise men. A.D. 362/63.

Men of the church now dominated the intellectual field. This is most likely the reason for the very modest number of preserved philosopher portraits from this period.

But in these same circumstances, the pagan philosophers gradually took on a new role. Their schools became repositories of Hellenism in this late phase, places where both classical learning and the cults of the gods were still maintained. It was only natural that, along with their intellectual activities, these late pagan philosophers also served as priests. Proclus (412–485) was still making public sacrifices to Asklepios, even though the emperor Theodosius had ordered the closing of all pagan temples in 391.

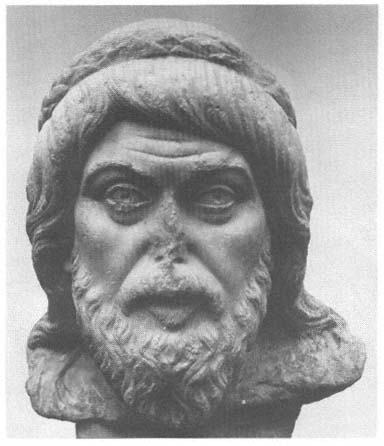

Of the few securely identified portraits of philosophers, to which I should now like to turn, it is significant that all of them save one wear the wreath or fillet that is the mark of priestly office. This makes clear how central the priesthoods had become to the identity of these Late Antique philosophers. It may be just an accident of preservation that these portraits all belong to the early fifth century (figs. 168, 170, 171). Typologically they are an astonishingly homogeneous group, even

though they have been found in very different parts of the Empire. All wear a beard and the thick, shoulder-length hair of Christ and the earlier "divine men." Their appearance is consistently elegant, the beard and hair neatly combed and parted, the garment impeccably draped. In contrast to the Christian ascetics, who neglected their outward appearance in the manner of the Cynics, the pagan "holy men" always remained an integral part of urban culture. Their style reflected their mainly aristocratic origins. The finest of the portraits are characterized by a remarkably dramatic facial expression turned upward, a trait not found in portraits of contemporary individuals. This must have a specific meaning, a point to which I shall return presently.

Given the striking similarities of these portraits, one might well question how true to life they can be, especially with respect to the long hair. These can hardly be realistic representations, since it is rather unlikely that all these men of advancing age had consistently luxuriant, full heads of hair. Could it be that the "divine" figures in the philosophical schools wore hieratic wigs or masks, like the earlier priest of Asklepios, Abonuteichos (cf. p. 263)?

The provenance of four of these portraits is known: Athens, Constantinople (Istanbul), Aphrodisias, and Rome. We can therefore assume that this last of the ancient types of intellectual portraiture was spread through the whole of the Empire.[64] The uniformity within the group also leads to the inference that differences among the various philosophical traditions no longer mattered in shaping the identity of the individual. The known provenances echo precisely what Garth Fowden has called the "topography of holiness." For along with the revived Platonic Academy in Athens, the major schools were located in the cities of Asia Minor—Pergamum, Ephesus, Sardis, Aphrodisias—as well as in Apamea in Syria and Alexandria in Egypt. It was in these great centers, which transcended regional boundaries and were closely linked to one another, that classical studies still flourished into the fifth century.

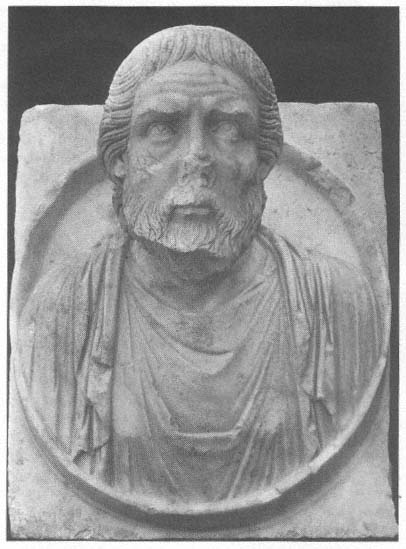

R. R. R. Smith has been able for the first time to reconstruct a specific setting for one of these portraits of an old philosopher, based upon the archaeological context of the recent discovery at Aphrodisias (fig. 168).[65] Together with several other tondo portraits, it decorated an exedra, which, along with a porticus and an apsidal room, was built

Fig. 168

Tondo from an apsidal hall: portrait of a contemporary philosopher.

Early fifth century A.D. Aphrodisias, Museum.

onto a wealthy residence of the Early Imperial period. The building was situated in the middle of the city, directly behind the well-known Caesareum. Smith adduces good reasons for identifying the complex as the location of the Neoplatonic philosophical school of Aphrodisias, where Asklepiodotus taught in the fifth century. He had studied with Proclus in Athens and later married the daughter of one of the richest citizens of Aphrodisias. The lavish decoration and central location of the school confirm that the philosophers of Aphrodisias still enjoyed public recognition and had access to substantial funds. The tondi, of course, were placed to be visible not from the outside, but rather from inside. That is, they served as inspiration to the teachers and pupils, not as a means of showing off to the public at large.

The preserved portraits and fragments fall into two different series. The one includes heads of ancient poets and philosophers, identified by inscriptions, some shown with their famous pupils (Aristotle with Alexander, Socrates with Alcibiades); also Pindar, Pythagoras, and Apollonius (presumably the one from Tyana). The other group comprises the contemporary philosopher, a beardless, rather youthful pupil, and a third contemporary male portrait, identified by Smith as a "Sophist." The latter two may be identified as members of a local family of honoratiores, who had accommodated the school in their home or been its benefactors in some other way. Unlike the first group, these carry no names inscribed, perhaps a token of modesty. Yet the head of the philosopher is larger than all the other portraits. He must have occupied a key position in the school's hierarchy.

A particularly interesting figure in this context is the so-called Sophist, who is also characterized as an intellectual yet is clearly several notches below the philosopher in status (fig. 169). The receding hairline and closely trimmed beard recall the "learned portraits" of the second century A.D. , which were in turn assimilated to great thinkers of the past (see pp. 225ff.). In contrast to the philosophers, his hair falls only to the nape of the neck, not onto the shoulders. He could also be a member of the school, one whose inferior spiritual rank is expressed through differences in hair and beard.

The whole program of busts of ancient philosophers and poets gives us some insight into the profile of the philosophical school. Classical

Fig. 169

Portrait of an amateur philosopher (?), from the same series as fig. 168.

Aphrodisias, Museum.

authors still constitute the foundation of its teaching, with the close teacher-pupil relationship highlighted by the famous pairs, that is, as models for the present-day relationship of wise teacher to pupils. The portraits of Pythagoras and Apollonius (Plato must have been in this series too) perhaps represent a particular branch of Late Antique Neoplatonic philosophy. The analogy with the famous teacher-pupil pairs underscores the close relationship between the contemporary philosopher and the beardless youth. Perhaps his parents had entrusted his entire upbringing to this philosopher. Porphyrius, in his Life of Plotinus, records that parents of the noblest families, just before their deaths, would entrust both their children and their fortunes to a philosopher as "divine and holy protector" (Plot. 9).

The visual program of the Aphrodisias school is not a unique instance. Evidence of tondo portraits of classical philosophers and poets

has also been found elsewhere. The choice of those deemed worthy of a portrait varied, but the principle was always the same. The presence of these classical authors was intended to certify the Late Antique philosophers as direct heirs to a long intellectual tradition. In the Early Empire there had already been galleries of portrait tondi in the libraries, representing the veteres scriptores (Tacitus, Annals 2.83). The Christians then adopted the same form of commemoration. Christ appears surrounded by the apostles, saints, and devout patrons, in the same manner as the pagan holy man with his classical authors, more advanced disciples, and boyish pupils.

The wisdom and divine revelation of the philosopher spring from the stores of classical learning. The portraits of the ancient poets and philosophers represent the whole of the Greek tradition, called up in order to confirm the authority of these latest teachers of wisdom. The law of Christ, on the other hand, is founded upon the divine kingdom of the teacher himself. The one series of portraits is retrospective, while the other looks ahead. Christ is the origin of all things, and all lead back to him.

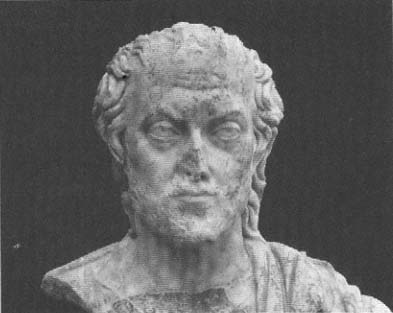

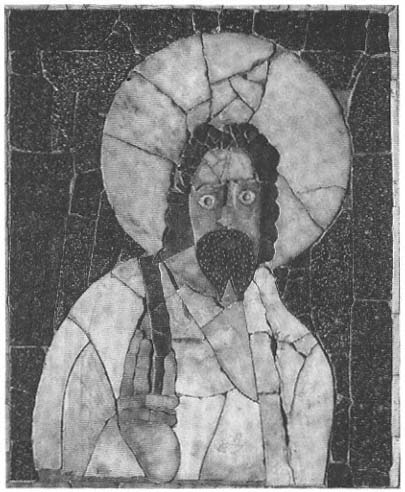

When the original context is lost, it can indeed be difficult in particular instances to distinguish the bust of a holy man from that of Christ in the same schema. Thus, for example, one might at first wonder if the impressive bust in Istanbul (fig. 170) could represent Christ. But in this instance the priest's fillet in the hair suggests instead one of the holy men. A problematic case is the bust of a teacher in Ostia with his right hand in a teaching gesture and a nimbus around his head, done in opus sectile technique (fig. 172).[66] The portrait was found in association with the tondo portrait of a youth in the lavishly decorated marble hall of a patrician house at the Porta Marina. The pairing of what seem to be teacher and pupil must, on the basis of the recent discovery at Aphrodisias, raise doubts about the widely held interpretation of the teacher as Christ. Likewise, two splendid scenes of animal combat with circus lions in much larger format on the same wall argue for a pagan setting. The chamber was abandoned before its completion, ca. A.D. 395. Most likely this was a kind of private philosophical school in the home of a wealthy pagan family, and the animal com-

Fig. 170

Bust of a contemporary philosopher. Ca. A.D. 400.

Istanbul, Archaeological Museum.

bats, as on some third-century sarcophagi, allude to the family's public benefaction of sponsoring the games. If this is the case, then the explanation for the interruption of building activity would be different from that proposed by Giovanni Becatti and Russell Meiggs. It was caused by the Christian reaction to the revival of pagan cults, especially under the emperor Eugenius (d. 394).

The usual interpretation of the hall as a gathering place for Christians rests on the identification of the sage as Christ, and this in turn rests largely on the nimbus. But as a representation of light, and hence a symbol of inner strength, this could be an attribute of a wide variety of figures and even finds a direct equivalent in the contemporary image of the "holy man."[67] About A.D. 485 Marinus described the philosopher Proclus thus:

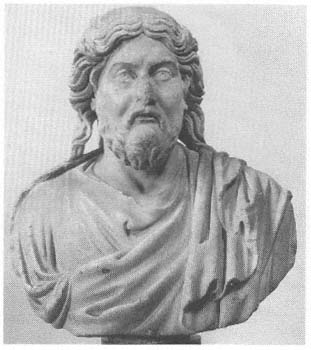

Fig. 171

Philosopher of the early fifth century A.D. Athens, Acropolis Museum.

He seems truly to have enjoyed a particular divine grace. The words issued from the wise man's mouth like snowflakes. His eyes were like lightning bolts, and his whole face was filled with a divine radiance. One day, when a high magistrate named Rufinus, a serious and distinguished man, came to his lecture, he actually saw a light running around Proclus' head. After the lecture he got up, threw himself before him, and bore witness under oath to this divine manifestation.

(Vit. Procl. 23)

Fig. 172

Opus sectile with the portrait of a Charismatic philosopher (theios aner )

in a nimbus. Ca. A.D. 395. Ostia, Museum.

Porphyrius had already recorded something similar of Plotinus, and in Eunapius' Lives of the philosophers, the gleaming eyes are a standard topos. The eyes of the divinely inspired wise man in Ostia have a particularly intense effect thanks to the colorful intarsia work. The viewer is practically blinded by the dark pupils set amid the big white disk.

In the mysterious rituals of theurgy, which were preceded by fasting, silence, and purification, philosophy became a kind of revelation that surpassed rational thought, a uniting of the soul with the divine. The unusual expressions of the heads in Athens (fig. 171) and Aphrodisias (fig. 168) may be consciously alluding to this mystery. In any case, the sculptors of both works were surely trying to render a state of inner arousal with the head turned upward, the emphatically opened eyes, the brows drawn up, and the lines in the forehead. All these traits are probably meant to convey a readiness for the divine, in expectation of the mystic experience. Everything depended on the degree of one's inner receptivity. As we have seen, the expressions of these "holy men" are entirely different from those of Hellenistic philosophers such as Zeno or Chrysippus (fig. 55), concentrated thinkers whose faces are marked by the will to understand and by the conviction that this can be achieved by dint of their own intellect. The philosopher-priest, by contrast, releases himself, listens expectantly to his inner voice, and turns his spirit into a vessel or a medium.

His expression of longing and of readiness is at the same time profoundly different from the sense of calm and illumination expressed in the portraits of Christ.[68] According to this interpretation, the notion of the "divine" would be represented in the "holy man" in the state of expectation of a higher good, the perfection of his earthly life. But he cannot make this happen, nor can he teach it, for it requires a divine gift that comes to only a few. The portrait in this way expresses something of the curious role of the Late Antique philosophers as élitist outsiders, who saw themselves more and more relegated to the margins of society, even though they usually came from established families and occasionally still served their cities in public office, as Fowden has shown. Christ, however, with his radiant visage, promises the blessings

of divine revelation to all the faithful. This was a message with which the pagan holy man could not compete.