Anacreon and Pericles

Our second example also involves the statue of a poet, but of a very different kind. In his description of the Athenian Acropolis, which he visited in the 170s A.D. , Pausanias mentions a statue of the poet Anacreon east of the Parthenon:

On the Athenian Acropolis is a statue of Pericles, the son of Xanthippus, and one of Xanthippus himself, who was in command against the Persians at the naval battle of Mycale. But that of Pericles stands apart, while near [plesion ] Xanthippus stands Anacreon of Teos, the first poet after Sappho of Lesbos to devote himself to love songs, and his posture is as it were that of a man singing when he is drunk.

(1.25.1)[30]

The statue of Pericles stood near the Propylaea and not far from the Athena Lemnia, a location intended to remind the viewer of Pericles' accomplishments as a statesman. Tonio Hölscher has rightly supposed that father and son were deliberately not placed together in order to avoid the impression of an undemocratic concentration of power in one family. The proximity of the statues of Xanthippus and Anacreon has been explained on the basis of a friendship between the two, though the evidence for this is uncertain.[31]

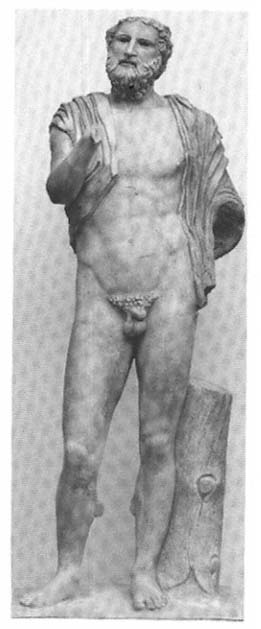

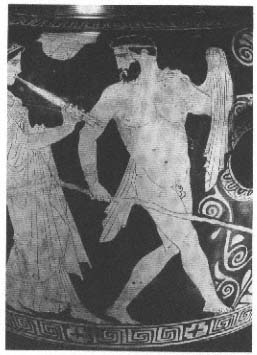

Of the statue of Pericles only copies of the head are preserved, while we know nothing whatever of the statue of Xanthippus. Thanks to one of those rare strokes of archaeological fortune, however, a statue found in the ruins of a Roman villa near Rieti gives an almost complete copy of the statue of Anacreon (fig. 12).[32] An inscribed herm copy of the same type secures the identification. That this is indeed

Fig. 12

Anacreon. Roman copy of a bronze

statue ca. 440 B.C. Copenhagen, Ny

Carlsberg Glyptotek.

the portrait seen by Pausanias is very likely, though, as often, incapable of definite proof. Pausanias' emphasis on the proximity of Anacreon's statue and that of Pericles' father suggests that the two were somehow connected. The statue of Anacreon can indeed be dated stylistically to the period when Pericles was in power, and probably originated in the circle of Phidias, who played such a major role in Pericles' Acropolis building program. It is only logical to assume that we are dealing with a dedication of Pericles or his immediate circle, as has often been thought.

But why would Pericles, of all people, at the height of his power, have wanted to honor posthumously this friend of aristocrats and tyrants, who first came to Athens and the court of the Peisistratids aboard an official trireme sent for him by the tyrant Hipparchus on the death of Polykrates of Samos, and had died at Athens a full two generations earlier at the ripe old age of eighty-five? Why should democratic Athens, on the eve of the Peloponnesian War, honor a poet associated above all with extravagant banquets and drunkenness (cf. Ar. Thesm. 163; Kritias, in Ath. 13.600E), the very embodiment of the soft and unmanly Ionian way of life?[33] Any answer to these questions must come from the statue itself.

The poet is singing and playing a stringed instrument, the barbiton . His enthousiasmos is best expressed by the way the head is slightly thrown back and turned to the side. The drunkenness, however, is indicated only very discreetly. Only when we set him beside other statues of the time, with their firm stance, are we aware of a slight instability of Anacreon, especially in a side view.[34] The poet is presented as a participant at a merry symposium, rather than as a poet as such. Hence also his nudity, the short mantle thrown over the shoulders, and the fillet in his hair, all elements of the iconography of Athenian male citizens, as we see them on countless red-figure vases, taking part in the symposium and subsequent komos . Singing and playing the barbiton are also characteristic of these drunken revelers.

Anacreon's contemporaries about 500 B.C. had in fact depicted him on vases as an older, bearded man in a long robe, dancing, and playing, surrounded by exuberant young revelers. Sometimes he wears a flowing mantle and the Ionian headgear that would later be mocked as

Fig. 13

Three revelers in elegant Lydian dress. Column krater, ca. 470–460 B.C.

Cleveland, Museum of Art. A. W. Ellenberger Sr. Endowment Fund, 26. 599.

effeminate—in the company of older revelers also clad in this exotic "Lydian" costume, including parasol, earrings, and pointy shoes. In the early fifth century, older Athenians did evidently still wear such outfits at komos and symposium (fig. 13), as a gay reminder of the good old days of their youth under the tyrant Peisistratus and his sons.[35] In any event, to judge from these vases, Anacreon was already during his lifetime a representative of the soft Ionian way of life and the uninhibited drinking party.

The image of the drunken singer is also the basis for the statue of Anacreon, though with a significant alteration. Unlike the vase painters, the sculptor shows the poet nude, with a handsome, ageless physique. Only the unusual length of the beard and fullness of the frame might be subtle hints of advancing age.[36]

A comparison with the well-known vase painting of Sappho and Alcaeus confirms that Anacreon is indeed depicted in the guise of a

Fig. 14

Sappho and Alcaeus on a krater or wine

cooler by the Brygos Painter, ca. 470 B.C.

Munich, Antikensammlungen.

symposiast and not as poet or professional singer (fig. 14). Alcaeus wears the long, flowing robe characteristic of singers and flute players and looks intently at the ground as he sings. (The painter has indicated the singing with little bubbles issuing from his mouth.) Sappho turns to him in admiration, attesting to the effect of his song.[37] This is, incidentally, one of our very few depictions of a female poet.

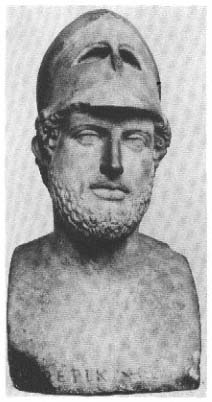

Anacreon is presented as the restrained and in every sense exemplary symposiast, quite unlike the uninhibited revelers, Anacreon himself among them, of Late Archaic vase painting. Drunkenness and ecstasy are hinted at with great discretion. The garment, is carefully arranged over the back and in front barely moves. The face shows no more emotion than the well-known contemporary portrait of Pericles

Fig. 15

Pericles. Herm copy of a bronze statue

ca. 440 B.C. London, British Museum.

Fig. 16

Anacreon. Early Imperial copy of the same

statue as fig. 12. Berlin, Staatliche Museen.

(figs. 15, 16). The point of this is clear: even on this jolly occasion the singer never loses his composure, and shows himself to be the very image of a model citizen of High Classical Athenian society, when it was none other than Pericles himself who set the standard of behavior. We may recall the stories of Pericles' conduct in public, and especially the tradition about his solemn, immobile countenance, which never registered joy or pain but lost its masklike composure only at the death of his youngest son (Plut. Per. 36; cf. 5).[38]

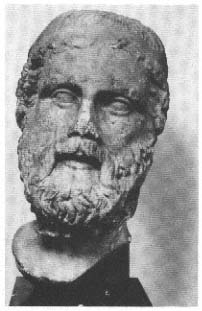

The head of a slightly earlier (though probably not Attic) statue of

Pindar may give some indication of the range of possibilities for facial characterization in this period (cf fig. 7).[39] Pindar is shown with the deeply wrinkled face of an older man, his strained expression best understood as a sign of intellectual activity. At the same time, as Johannes Bergemann has pointed out, the old-fashioned and carefully stylized beard could be meant to associate the poet with the conservative and luxury-loving aristocratic circles for whom he composed his verse. Such biographical traits are entirely possible in this period, as we can also see, for example, in the statue of an elderly poet who rushes off with an energetic stride, evidently toward a specific goal. Even if this figure has thus far resisted interpretation, it is nevertheless clear that we are once again dealing with a specific biographical element.[40]

Just as Pindar has a look of severity and concentration, so we might well have expected for Anacreon an expression of gaiety and delight. Instead, Anacreon's face is so fully devoid of emotion that, in a copy that omits the characteristic turn of the head, we might easily have mistaken him for a king or hero.[41] Such was the determination of the sculptor to emphasize the subject's exemplary behavior, just as in the portrait of Pericles.

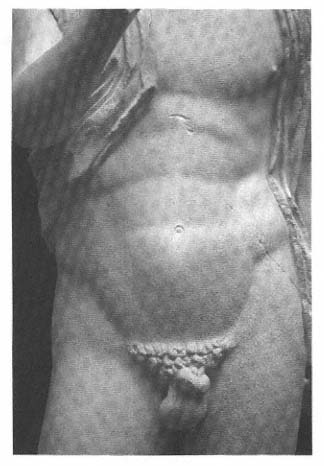

The way the mantle is draped actually emphasizes the poet's nudity and calls attention to a striking detail that has barely been noticed before: he has tied up the penis and foreskin with a string, a practice known as infibulation (or, in Greek, kynodesme ) (see fig. 17). The explanations for this practice in ancient authors—as a protective measure for athletes or a token of sexual abstinence in a professional singer (Phryn. PS 85B; Poll. 2.4.171)—all come from relatively late sources and are not satisfactory in the present instance.[42] But many examples of kynodesme in contemporary vase painting (fig. 18) suggest another explanation. Here it is almost exclusively symposiasts and komasts who have their phallus bound up in the same manner as Anacreon, and as a rule they are older men, or at least mature and bearded. Satyrs are also so depicted, evidently for comic effect.[43] To expose a long penis, and especially the head, was regarded as shameless and dishonorable, something we see only in depictions of slaves and barbarians.[44] Since in some men the distended foreskin may no longer close property, allowing the long penis to hang out in unsightly fashion, a string could be

Fig. 17

Detail of the statue of Anacreon in fig. 12 showing kynodesme .

used to avoid such an unattractive spectacle, at least to judge from the evidence of vase painting. The vases also make it clear that this was a widely practiced custom. We may then consider it a sign of the modesty and decency expected in particular of the older participants in the symposium. Once again, in the ideology of kalokagathia , aesthetic appearance becomes an expression of moral worth.

The borrowing of this detail from the world of Athenian daily life

Fig. 18

Symposiast with his penis bound up.

Stamnos by the Kleophon Painter, ca. 440

B.C. Munich, Antikensammlungen.

lends a realistic element to the nude figure. This Anacreon is no longer the representative of an extravagant and decadent bygone way of life. He becomes instead a contemporary, whose conduct at the symposium is a model of restrained and proper enjoyment. By underlining his nudity, the statue celebrates the perfection of the body, just as those of younger men. This Anacreon is a handsome and distinguished man, a kaloskagathos . In the Athens of this period, when the Parthenon was going up, it is hard to understand a statue like this as anything other than an exemplar of correct behavior, expressing precisely what Thucydides puts in the mouth of Pericles in his famous Funeral Oration (2.37, 41), the praise of Athens for its festivals and enjoyment of life;

thus the statue is a vision of the perfect citizen. In Athens, physical exercise and military training are not part of a hardened and joyless way of life, as in Sparta; rather, they are part of the pleasures of a free and open society.[45]

For all the iconographical similarities between Anacreon and the komasts in vase painting, we should not forget that the same image, when isolated and magnified to the scale of a life-size portrait statue, takes on a very different public character and meaning. Only in this context does it become the exemplar of certain social values. In fact in this period, the symposium was becoming less popular as a subject for vase painting, and the symposiasts themselves are mostly depicted behaving rather modestly and properly, as if following the model of Anacreon.[46]

When the Athenians saw Anacreon, the poet of the celebration, beside the great general Xanthippus, they had before them two prototypes, together representing the twin ideals of Athenian society that blend so harmoniously in Pericles' vision. We might note, however, that the Corinthian envoys at Sparta accuse the Athenians of being just the opposite (Thuc. 1.70). Because of their fierce ambition and nationalism, "they go on working away in danger and hardship all the days of their lives, seldom enjoying their possessions because they are always adding to them. Their idea of a holiday is to do what needs doing." Whether or not such charges were made in reality, and whether justified or not, one thing is clear: the honoring of Anacreon, the poet of the symposium, at this location, in this form, and at this point in time must surely have had a programmatic character. The statue proclaims that gaiety and enjoyment are as much a part of the superior Athenian way of life as sports and warfare, and that life was as pleasurable and happy in this new age of Periclean democracy as it had been in the old days of the tyrants and their "Lydian" decadence.[47]

Whether my interpretation is entirely correct or not, this posthumous statue of Anacreon stood for a very specific set of values. That is, its purpose was less to celebrate an individual famous poet than to be the embodiment of a certain social ideal: the poet as exemplar. In principle this would still be the case if the statue had instead been put up by the opposition camp, the oligarchs.[48]