The "Gentrification" of the Philosopher Portrait: Carneades and Poseidonius

This new state of affairs must naturally have had some impact on how contemporary intellectuals saw and presented themselves, especially in the philosophical schools of the Late Hellenistic period. Whereas philosopher statues of the third century had posed a challenge to society

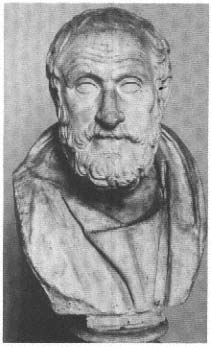

Fig. 95

Carneades (ca. 214–128). Bust (now lost) after

an honorific statue ca. 150 B.C. Copenhagen,

Museum of Art. (Cast.)

in their bold indifference to conventional norms and their claim to spiritual leadership, those of later philosophers gradually adapt themselves to these very standards of the bourgeois image. With the growing rivalry between the philosophical schools, the stark contrast in image of earlier times eventually disappears.

When a statue of the celebrated philosopher Carneades was dedicated in the Agora by two Athenian citizens about the middle of the second century or just after (fig. 95), the sculptor took as his model the statue of Chrysippus not far away (fig. 54).[38] Both were depicted seated and giving instruction, turning their concentrated attention to an imaginary interlocutor. The similarity is quite surprising, for Carneades was the head of the revived Platonic Academy, and his own

fame was due not least to his lifelong struggle with the dialectic of Chrysippus. He was supposed to have said of himself. "Without Chrysippus there would have been no Carneades" (D. L. 4.62).

However striking the similarities to the older portrait, there are also differences. Like the standard honorary statues of the day, Carneades wears a chiton under his himation. Toughness and the refusal to succumb to the needs of the body and one's own mortality are no longer a part of the philosopher's message. In place of the careless external appearance and passionately aggressive energy of Chrysippus, we see an elegant figure, with well-groomed beard and a countenance of fine proportions derived from Late Classical art. Yet the strenuously raised furrows of the brow recall at first glance the expressions of the Stoics. If we compare this, however, with the portraits of Zeno, or even Chrysippus (cf. figs. 53, 60), it becomes clear that in Carneades a different kind of thinking is meant: not the vigorous and direct attack on an opponent, but rather a distanced scrutiny and weighing of arguments. Interestingly the contraction of the brows that was so characteristic of third-century portraits is no longer present. Instead, the deep furrows running in "orderly" parallel lines dominate the facial expression. This is a man of contemplation, who listens carefully and calmly formulates his argument. The portrait makes no particular ethical claims.

The fact that the statue quotes from an earlier Hellenistic philosopher portrait seems to be not a special case, but rather symptomatic of a broader trend. By the mid-second century, the great poets and philosophers of the previous century already enjoyed the status of classics. This retrospective tendency, which had informed so much of Hellenistic culture by the middle of the second century, is particularly tangible here. This backward-looking stance is accompanied by a kind of eclecticism, which had the effect of smoothing over any uncomfortable disagreements between philosophical schools. Under these circumstances, it is not so astounding after all if the image of a Stoic is taken as the model for that of the leader of the Academics.

There is yet another way in which the portrait of Carneades differs from that of his predecessor. The long hooked nose and crooked

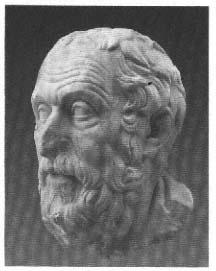

Fig. 96

Carneades. Roman copy of the period of

the emperor Trajan. Munich, Glyptothek.

mouth, which are well preserved in a new copy in Munich (fig. 96), are striking features of an unmistakable, individual physiognomy. For the first time, a Hellenistic portrait of a philosopher clearly reveals the man himself, as an individual, not merely in his role as the representative of a particular school. Not surprisingly, of all the philosopher statues in Athens, this one made the greatest impression on the young Cicero (Fin. 5.4).

In the course of the second century, philosophers of every stripe were steadily integrated into urban social and political life. A typical example is Athens, which in the year 155 B.C. sent the heads of three philosophical schools, the Stoa, the Peripatos, and the Academy, as envoys to Rome (where Carneades held his famous speeches for and against justice). In 124/3, the polls officially recognized these same three schools as centers of education, and at the funeral of the great

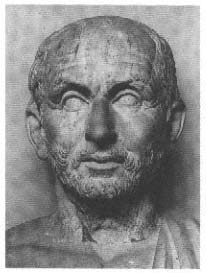

Fig. 97

Stoic philosopher of the late second century

B.C. , perhaps Panaitios (died 109 B.C. ). Roman

copy. Rome, Vatican Museums.

Stoic Panaitios all the philosophers in Athens took part as a corporate entity. There was a reconciliation between Epicureans and Stoics, and some Epicureans even agreed to serve as public magistrates.[39]

Along with this rapprochement of the philosophical schools, it appears that the differentiation of the portraits according to school that had been the norm in the third century, expressed in particular mimetic and physiognomic formulas, gradually disappeared, to make way for a more general look of contemplation. This is the same look, as we shall soon see, to which many citizen portraits of the period also adapt. There are, unfortunately, no securely identified philosopher portraits of the later second century. The portrait of a man with unusually large eyes might be that of a Stoic (fig. 97). The closely shorn but untended beard recalls Chrysippus, while the forehead raised in a gesture of skepticism is closer to Carneades. The portrait is preserver in three

copies found in Rome and must represent a popular figure in Late Hellenistic philosophy. A possible candidate would be Panaitios, who molded out of the classical tradition a straightforward and pragmatic ethical theory well suited to the needs of Roman aristocrats. The style of the portrait would be consistent with a dating toward the end of his life in 109.[40]

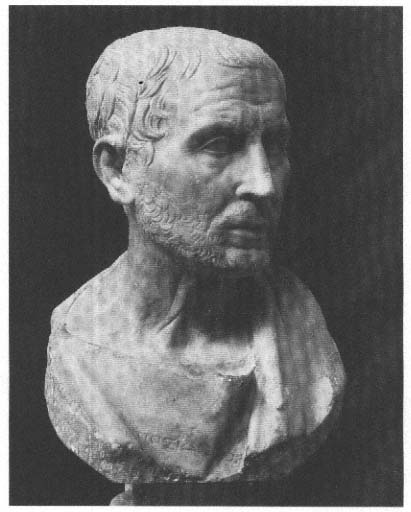

The end of this development may be represented by the portrait of Poseidonius of Apamea in Syria (ca. 135–50 B.C. ), created about 70 B.C. (fig. 98). Poseidonius was a pupil of Panaitios and, like him, taught on the island of Rhodes. The portrait is known from only a single copy of superb quality, a bust of early Augustan date.[41] From the preserved portion of the chest we can infer that the figure was standing and clad in chiton and himation, thus no different from standard portrait statues of contemporary Greeks and essentially the same as those of the fourth century B.C. The modest expression no longer betrays him as a philosopher, and certainly not as a Stoic struggling with his thoughts. In fact only the beard signals the philosopher, and it is so closely trimmed as to be barely noticeable. Nevertheless, unlike the beard of the so-called Panaitios, this one has been carefully trimmed. A number of contemporary portraits are known from Rhodes featuring this kind of closely trimmed beard, but it is unlikely that all of them are philosophers. Rather, it must be a kind of "philosopher look" that was fashionable in this university town. The typical citizen image and the would-be philosopher seem, at least on Rhodes, to have become virtually indistinguishable.

Most striking, however, in the portrait of Poseidonius is the self-consciously classicizing quality, which becomes almost oppressive in the "Polyclitan" locks of hair. This is the hallmark of a man who saw it as his primary responsibility to gather the spiritual heritage of the Greeks and pass it on to the Romans who flocked to his lectures. For a man of his eclectic philosophy, there would have been no point in modeling his image after that of Chrysippus. There is nothing left in this portrait of intellectual passion. The quiet, serious features are those of a tenured professor, self-satisfied both with his own methods

Fig. 98

Poseidonius (ca. 135–50 B.C. ). Roman bust after an original

of the philosopher's lifetime. Naples, Museo Nazionale.

and research and with the recognition accorded him by his pupils and by society, a man who identifies fully with the values of that society and has no more interest in changing it.

Yet in spite of these changing circumstances, the philosopher remained a figure of great authority in the Late Hellenistic age. His reputation now rested primarily on his role as interpreter of the classical tradition. For example, a certain Hieronymos, active on Rhodes in the second century B.C. , had himself depicted, on the doorway of his funerary naiskos, reading and lecturing to a circle of his pupils. Characteristically, he holds an open book roll from which he reads and interprets the text.[42] The role of interpreter is in turn closely linked to that of the educator and counselor.

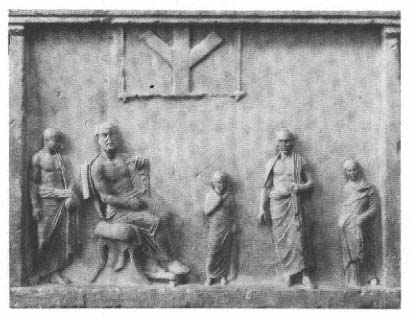

This association is well expressed by a relief of the first century B.C. (fig. 99) that has provoked a great deal of interest on account of a mysterious psi-shaped symbol.[43] Underneath the large framed picture (or window?) bearing the enigmatic sign, a philosopher is seated with his family. His portrait, like that of Poseidonius, is patterned after Late Classical models. Although he has no other heroic traits and sits comfortably in a chair, he is shown on a much larger scale than all the other, standing figures. This is presumably a grave monument that a father commissioned for the resident philosopher to whom he had entrusted the education of his three children. The difference in scale is supposed to convey the great awe in which the teacher is held, and the success of his teaching is expressed in the well-bred manners and poses of the children, a young man, a youth, and a girl. The father is characterized by his bald head and realistically rendered face as an unmistakable individual and wears the same outfit as the philosopher and elder son, a himation without a garment beneath it. This is not the current fashion and marks him as an adherent of the philosophical way of life. If we interpret the curious symbol above the philosopher as a psi, it could be a reference to the concern for the peace and security of the soul common to all those depicted here. The intimate ambience of the scene brings to mind the Greek philosophers employed in the households of contemporary Roman aristocrats. But there, no matter how much the Romans valued the company of the philosopher and

Fig. 99

Grave relief (?) of an in-house philosopher with his host family.

First century B.C. Berlin, Staatliche Museen.

relied on his advice in times of spiritual crisis, they would not have accorded him such a position of honor within the family. The relief is thus a particularly impressive testimony to the high status accorded philosophical teaching in the Late Hellenistic world.[44]