The Divine Homer

There can be little doubt that one's expectations and attitude toward such a statue as that of Homer on the Archelaos Relief, almost more of a cult image, are quite different from how one might approach the traditional honorific statue for a poet or philosopher. The ancient viewer was invited to discern and reflect upon the biographical and literary elements present in the image, to meditate piously upon them in the spiritual setting of a shrine. It was this aura of the sublime that was evidently the very effect aimed at in a number of the retrospective portraits.

It is this particular aspect I should like to focus on in considering the famous portrait of the blind Homer.[21] Again we have copies of only the head, but some idea of the body may be supplied by the Archelaos Relief and the coin types (figs. 85, 86) that depict Homer as extremely old and blind. The tradition of Homer's blindness is an old one, as we have seen, perhaps derived originally from the blind singer Demodokos in the Odyssey . In any case, it is certainly present in the well-known portrait of the elderly Homer created about 460, with which we have dealt in chapter 1 (fig. 9). The blind Homer was, nevertheless, always only one of several ways of portraying the poet, as the other versions on coins attest. But whereas the early portrait, created at the time of the "Severe Style," conveys a sense of profound calm, the Hellenistic sculptor has rendered his vision of Homer in highly dramatic terms (fig. 89). If the earlier portrait merely hinted at the

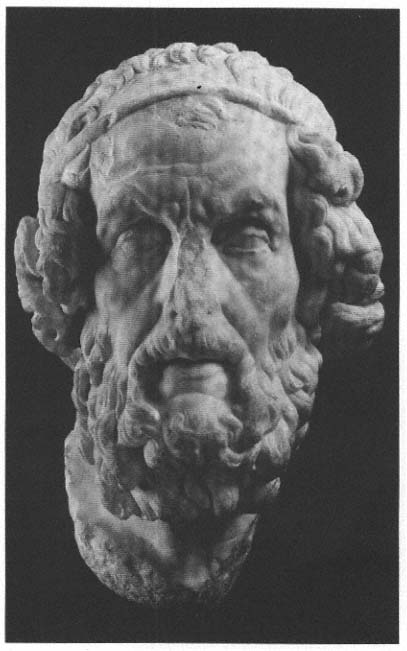

Fig. 89

Homer. Roman copy of a High Hellenistic statue ca. 200 B.C. Boston,

Museum of Fine Arts.

blindness in the closed eyes, here it is rendered with almost clinical accuracy, with the eves half-closed and the muscle degeneration around them. And if the early portrait presented a figure that, for all its loftiness, might still be likened to images of contemporary older men, this is now out of the question. The Hellenistic portrait belongs to another category. The heavy, archaizing locks framing the face, the fillet containing the hair rolled up in the back—also an archaizing trait—and the full, heavy beard all conjure up the majestic aura of a god.

The deep-set, lifeless eyes and the whole expression of the facial features are in certain ways rendered very variously by the Roman copyists. As in the case of Menander, it seems to me hardly possible to reconstruct an authentic version of the prototype out of the more than twenty-five surviving copies. Once again it is precisely the copies of highest quality that may turn out to be instead interpretations of the original, pursuing their own interests and intentions. Roughly speaking, the copies may be divided into two groups. Some sculptors emphasize the active features of the face, others the passive. One group of copies emphasizes the intricate forms of the coiffure, especially the archaizing rounded locks at the temples, while the other confuses these, sometimes in an apparently intentional attempt to render a wild and unkempt mass of hair. We may best illustrate the difference in a juxtaposition of two of the most impressive copies, though bearing in mind that because the two are so outstanding in workmanship, they will have absorbed much of the Roman taste of the period in which they were carved.

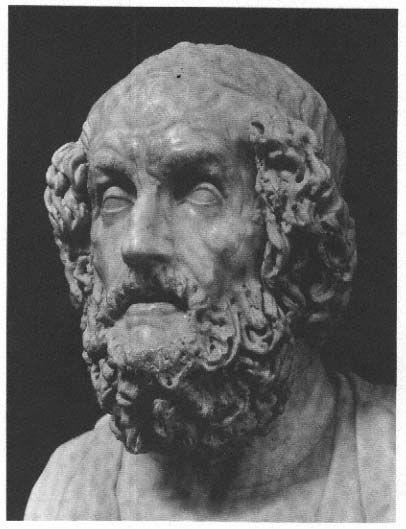

A head in Boston, probably of Flavian date, stresses more the active features (fig. 89).[22] Brows and forehead are overlaid with little rippling muscles that seem to be in continual irregular motion. Our impression is of a fervid imagination in high gear, and we barely notice the elements of decrepit old age. In the famous head in Naples, on the other hand, a Late Antonine copy, the dominant impression is of the frailty of old age (fig. 90).[23] The visionary aspect is linked to a sense of agonizing struggle. The forehead is almost painfully drawn up, and the eyes and face have a kind of dead look. It was this head that the young

Fig. 90

Homer. Roman copy of the second century A.D. after the same

statue as fig. 89. Naples, Museo Nazionale.

Goethe had in mind in his impassioned description for Lavater's Physiognomische Fragmente:

I enter the presence of this figure uninformed. I say to myself: the man sees nothing, hears nothing, doesn't move, doesn't react. In this head, the midpoint of all the senses is in the high, gently arching hollow of the brow, the seat of memory. Every image is stored here; all the muscles rise up, to conduct the figures of the living down to the cheeks that will give them voice. . . . This sunken blindness, the vision turned inwards, energizes his inner life all the more, and makes the father of poets complete. These cheeks have been molded by never-ending speech, these muscles of speech the well-worn paths down which gods and heroes have made their way to mankind; the willing mouth, only the gateway to such images, seems to babble like a child's, has all the naïveté of youthful innocence; and the enclosure of hair and beard contains and ennobles the breadth of the head.[24]

In the Boston head, in contrast, the power of the will wins out, especially in the mouth and eyes: the mouth holds firm, trying to shape into words the vision of the mind's eye. Even if none of the copies can be proved to be the most "reliable," we must nevertheless once again assume that the original somehow combined the different and sometimes contradictory traits captured in the varying interpretations of the copyists: physical frailty and extreme old age, on the one hand; a god-like loftiness and dazzling inspiration, on the other. The head in Boston and others of its type, with the complicated treatment of the hair and facial features, come closer, in my view, to the High Hellenistic original than the group to which the head in Naples belongs. One could imagine the Boston head joined to an imposing seated statue of the type on the Archelaos Relief, but not the head in Naples. Perhaps the High Hellenistic prototype was adapted by a Late Hellenistic sculptor who stressed such elements as the frailty of age and the unkempt hair and beard of the old man. But since these later copies do not share any features that clearly distinguish them typologically from the version to which the Boston head belongs, it is probably more likely that the Naples head and others like it are independent

variants whose only common element is a reflection of the style of the Antonine period.[25]

Nevertheless, the important point for our interest is that the reinterpretation of Homer's face continued uninterrupted into the Imperial period and that the copyists were neither able nor willing to conceal their own conceptions of the great poet. We should also remember that the Roman patron had, at least theoretically, not only a choice among the different versions of this particular type, but a choice of several types as well. (In addition to the two versions of the blind Homer just discussed, there was yet another popular type, probably Late Classical in origin, showing Homer with the wide-open eyes of the seer and long hair at the nape of the neck, the so-called Apollonios type.) The various portraits, with their diverse emphases, were of course meant to evoke in the viewer a whole range of associations. Alongside the enthroned prince of poets, the seer heralding the gods and heroes, there may be another conception, exemplified by the pseudo-Herodotean bios, of Homer as a poor singer wandering from city to city. This image, however, first became widespread only in Imperial times.[26] It could be the inspiration for the head in Naples and others like it.