The Cult of Poets

Though literary and intellectual in conception, these retrospective portraits, in the purposes they served, went far beyond the interests of a small circle of scholars. The reading and interpretation of literary masters was not restricted to the "bird cages" at the royal courts. The

great library at Alexandria itself was open to all who wished to study and read. Indeed, the preoccupation with literature seems to have become a kind of all-embracing social dialogue in Hellenistic Greek cities of the third and second centuries. While the youth were educated in the classics and made to learn them by heart, their elders would congregate at the gymnasia to hear an itinerant scholar, poet, or philosopher, or other speakers employed by the city. These public lectures often focused on the interpretation of great writers of the past. In this way, the poets of old and the philosophers were elevated to the status of authorities who provided guidance in all of life's important matters. Cities would institute genuine hero cults for their own intellectual heroes, complete with appropriate sacrificial rituals. The establishment of such cults is in itself of less interest for us (kings and benefactors also enjoyed this highest form of public honor) than the artistic elaboration that they occasioned and inspired.

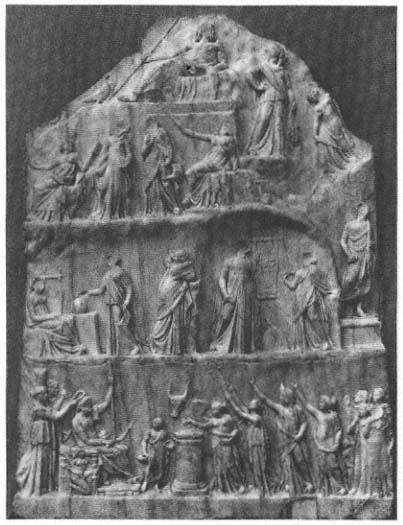

At the very top of the hierarchy, of course, stood Homer, the font of all wisdom, religion, and culture. The relief of the sculptor Archelaos of Priene (fig. 85a, b) translates into visual terms a complete vision of Homer as the ancestor of Hellenic culture.[14] The monument was probably the votive relief of a contemporary poet who had won a tripod in a poetic contest (perhaps in honor of Homer himself) and dedicated it, along with a statue of himself, to Apollo and the Muses. His simple draped statue stands at the right, just at the foot of the hill of the Muses. Below, we are looking into a sanctuary of Homer. He is enthroned, like Zeus, a tall scepter in his right hand and a book roll in the left, while the personifications of the various literary genres, arranged in a careful hierarchy (Historia, Poiesis, Tragodia, Komodia), sacrifice a bull in his honor. The sacrificial attendant is a boy called Mythos. The master's twin works, Iliad and Odyssey, kneel beside the throne. In front of the footstool, two mice nibble on a roll, probably an allusion to the Batrachomyomachia, which was then considered a genuine work of Homer. From behind the throne, the standing figures of Chronos and Oikoumene crown the poet.

Unlike the other figures, these two bear unmistakable portrait features, probably a discreet homage to a royal couple whom we can no longer identify. They may have been responsible for the splendid Homereion depicted here or another one like it. Four female figures

Fig. 85 a

Votive relief of a poet in honor of Homer, by the sculptor Archelaos

of Priene. Ca. 150 B.C. London, British Museum.

on a smaller scale watch the sacrifice from a corner: Arete and Mneme (Memory), with their younger sisters Pistis (Faith) and Sophia. A little girl, Physis, turns to Pistis with a look of supplication and tugs at the hem of her sister, who bids her be silent.

The whole is an extravagant panegyric, celebrating the central im-

Fig. 85b

Detail of an etching. From Ex calcographia Domenici de Rubeis (Rome, 1693).

portance of Homer and, through him, of literature and poetry in education. Particularly striking is the great value attached to certain skills. Among all the Muses, their mother, Mnemosyne, is singled out and stands closest to Zeus. The message of this relief is clear: the standards for the education of the young must be derived from the great literary works of the past, for these are the source of cultural memory. But those writers themselves are all nourished by a single source, Homer. This is truly an image to warm the heart of a classical philologist.

The Archelaos Relief not only presents us with an all-encompassing vision of learning but also gives some idea of how statues of Homer may have been set up in the numerous sanctuaries of the poet in Hellenistic cities that are attested in the literary sources. The Homereion in Alexandria is described as follows by Aelian: "Ptolemy Philopator erected a temple to Homer and placed within it a magnificent seated statue of the poet and, in a semicircle around him, all the cities that laid claim to Homer" (VH 13.22). We may suppose that these various cities, personified in statues in the Homereion at Alexandria, also had richly outfitted sanctuaries of Homer. One that is well attested was in Smyrna, where Strabo saw a temple with cult statue (xoanon ), surrounded by columned porticoes. His use of the word xoanon implies a particularly ancient-looking cult statue, perhaps of wood. This was no doubt intended to legitimize the city's claim to being Homer's birth-

place. "The people of Smyrna have a special claim to Homer, and they even call a bronze coin the Homereion," observed Strabo (10.1.37). But cities of the Greek mainland also accorded the father of poets cultic honors. We hear, for example, of sacrifices conducted by the Argives at a bronze statue of Homer (Cert. Hom. et Hes. 18).

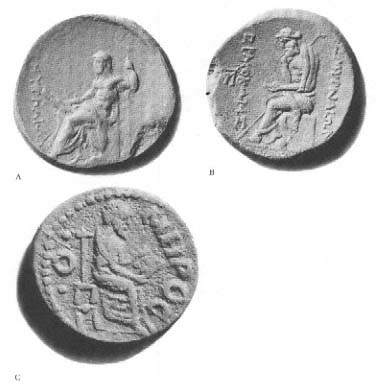

In addition to Homer, many other intellectual heroes enjoyed cult worship. In Priene, for example, stood a heroon of Bias, who had for centuries been numbered among the Seven Wise Men. This small city even issued silver coins about the middle of the second century B.C. with a full-length figure of Bias, probably a rendering of the statue that stood in the "Bianteion" (fig. 86b). The coin depicts a tripod alongside the statue, an allusion to an often-told story. One day in Priene, some people found a golden tripod at the shore bearing the inscription "For the wisest." The city awarded the tripod to Bias, but he in turn, in pious modesty, dedicated it to Apollo (D. L. 1.82).[15] We see here how such a heroon attracted cult legends, just as did the sanctuaries of the traditional gods and heroes, and how cities would strive to propagate these legends, like that of Bias' tripod, throughout the Greek world.

The Archilocheion on Paros, which probably dated back to the Archaic period, was, like other heroa, associated with the poet's grave and a gymnasium.[16] In the third century, a Parian named Mnesiepes ("Collector of Epics") had a temple in honor of Archilochus either built or renovated, by order of the Delphic oracle. A long, partially preserved inscription tells legends from the life of the poet that the dedicator claims to have collected from ancient tales. In reality these stories are paraphrases of Archilochus' poetry, including the story, modeled on Hesiod, of how he was called by the Muses, who made him a gift of a lyre as he was driving a cow to market. A later inscription, of the first century B.C. , contains a list of the poet's writings and deeds in chronological order.

These dedications, with their detailed reports of the life and work of Archilochus, "testify to the poet's continued importance to the people of Paros, who would visit the shrine and read the inscriptions. It is significant that what interested them about Archilochus was not so much his poetry as the relationship of his poetry to his life."[17] In this instance, the sanction of Delphi was particularly important, not only for the cult on Paros, but for its fame beyond the island. Paros

Fig. 86 a–d

Four Hellenistic coins of Greek cities, representing local intellectual heroes

of the past: a, Archilochus of Paros: b, Bias of Priene; c, Anaxagoras of

Clazomenae; d, Stesichorus of Himera (photos enlarged).

issued coins in the first century B.C. with a portrait of the poet as a youthful figure nude to the waist, holding a lyre in his left hand and a book roll in the right (fig. 86a).[18] His one-time reputation for slander and dubious citizen conduct was long forgotten, and all that remained was his fame as a great poet.

There were other cities as well that were putting their intellectual heroes on coins by the second and first centuries B.C. Clazomenae, for

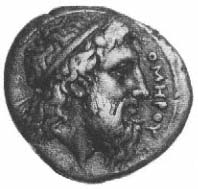

Fig. 87

Homer. Coin from the island of Ios (3:1). Berlin,

Staatliche Münzsammlung.

example, minted coins showing the philosopher Anaxagoras (fig. 86c), and Sicilian Himera the poet Stesichorus (fig. 86d), both represented as vigorously active figures. Stesichorus sings and plays a stringed instrument, while Anaxagoras is shown as a teacher, in the same pose as Hermarchus. The majority of such coins, however, appear first under the Roman Empire. Yet such early examples as those just mentioned suggest how important these figures were to the Greek cities already in the Hellenistic period, both for their image of themselves and for their understanding of their own traditions.[19]

Most numerous, however, are the coin portraits of Homer,[20] minted in several of the cities of Asia Minor. The little island of Ios, for example, which claimed to possess the tomb of Homer, had already in the fourth century B.C. circulated splendid silver coins with a head of Homer that, without the inscription, could easily be mistaken for an image of Zeus with flowing locks (fig. 87). The die cutter probably did in fact simply use a Zeus type with which he was already familiar. We see from this how early Homer was turned into a mythical figure, and how the assimilation of his image to that of Zeus derived from an earlier notion of Homer's unique significance. The figure of the singer is assimilated to that of the gods and heroes of whom he sang.

Fig. 88 a–c

Homer on coins of the cities of Smyrna (a–b ) and Chios (c ).

The city of Smyrna minted several different portrait types, starting in the first half of the second century B.C. , some of them simultaneously. Not all of these images could be based on existing statues, much less "cult statues." This variety shows clearly the intense fascination of Homer in this period, how the popular imagination constantly reshaped his image, while at the same time imagery of the Olympian gods could only imitate fixed Archaic and Classical prototypes. The most popular coin type of Homer in Smyrna shows a Zeus-like enthroned figure, as on the Archelaos Relief, holding a scepter and (in place of the thunderbolt!) a book roll. In one of the earliest issues, he is even more closely assimilated to Zeus, with bare chest and the right hand, with the book roll, outstretched in a commanding gesture (fig. 88a). At the same time, however, beginning in the decade 180

to 170, Smyrna also issued a contemplative Homer, with the head propped on one hand (fig. 88b). Later came other images, the poet reciting dramatically from his work and, on nearby Chios, the poet quietly reading in his Iliad (fig. 88c). This incongruous notion of the quietly reading Homer was also a Hellenistic innovation, in some other medium (cf. fig. 104). The activities of Homeric scholars and connoisseurs are, as it were, retrojected onto the poet himself. The act of reading, of meditating on and immersing oneself in his verse, acquires an almost religious aura.