Wisdom and Nobility: An Early Portrait of Homer

Of the earliest known portrait type of Homer, a life-size statue created about 460 B.C. , only copies of the head are preserved.[15] The form of

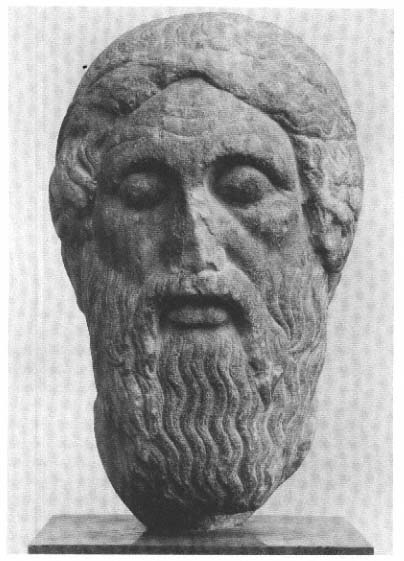

Fig. 9

Homer. Early Imperial copy of a portrait of ca. 460 B.C. Munich, Glyptothek.

the body is unknown, as are location, patron, artist, and occasion. Nevertheless, we can still reconstruct some sense of the conceptual framework of this portrait type. A subtly carved head in the Glyptothek in Munich (fig. 9) of the Early Imperial period seems to give a reliable copy of the original. Its fidelity is confirmed by two other, less finely worked examples, which in turn enable us to spot the divergences in the remaining copies.

The sculptor imagined Homer as a blind old man, turned slightly to one side and listening to his own inner voice. Old age does not carry negative connotations here, as so often in Greek poetry. Signs of decrepitude in the cheeks, temples, and the deeply sunken eyes are indicated with the utmost discretion. This Homer is a handsome old man—kalos geron —full of dignity. This is best expressed in the long, carefully arranged hair and lush, well-tended beard, as well as other features of the physiognomy, such as the full lower lip. Above all, the treatment of the locks of hair on the brow contributes to this impression of beauty and nobility.

The hair is carefully arranged over the skull and held in place by a band or fillet, while on the sides and in back it falls freely in thick locks. The bald pate that is typical of the iconography of old men is, in addition, concealed by a complicated arrangement: two broad strands are drawn from the crown forward and knotted over the brow. This both calls attention to the subject's baldness and at the same time artfully hides what might detract from his beauty. Similarly, the long locks on the sides are intended to mitigate the sunken cheeks.

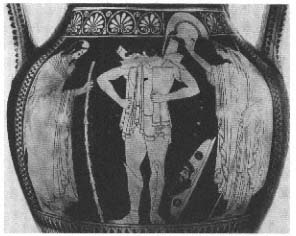

That this arrangement of hair over the forehead is a realistic feature, a hairstyle that men actually wore, is confirmed by a vase painting of ca. 510–500 B.C. , in which Priam wears strands of hair similarly knotted over his bald head (fig. 10). This must be a fashion for old men of the Late Archaic period, which reflects in turn the negative associations of old age and its effect on the body. The aristocrat tries to conceal the less attractive features of the aging process.[16] This particular Late Archaic coiffure was probably out of fashion by the time the portrait of Homer was made, thus characterizing him as a distinguished older man of an earlier generation. We are reminded of the noble old men who advise their king in Greek tragedy.

Fig. 10

Hector arms for battle; at his left, his aged father,

Priam. Red-figure amphora by Euthymides, ca. 500

B.C. Munich, Antikensammlungen.

The notion of Homer's blindness is an old one, first attested by the sixth century (Hymn. Hom. Ap. 172). The model for it is most likely the portrayal of the blind singer Demodokos in the Odyssey (8.62ff.). Even before that, the figure of the blind singer was widespread in Egypt and the Near East. Perhaps this conception arose from a common experience of early civilizations, that the blind often had unusually good memories, a talent that made them useful.[17] In the portrait, however, blindness is not presented so much as a biographical detail, but as a prerequisite for the poet's extraordinary memory and wisdom. Just as the closed eyes are charged with meaning and more than just a realistic touch, so too the lines in the brow signify more than just age. Their strict parallelism looks rather emblematic and probably alludes as well to the poet's prodigious powers of memory. It is surely no coincidence that the same lines appear on the brow of the old seer lost in meditation from the east pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia.[18]

True knowledge is ancient knowledge. The composing of verse is conceived in this portrait as a gift from the gods, akin to that of the

seer, a form of revelation. Greek mythology is full of seers and poets whose powers are directly connected with their blindness. This is true, for example, of Demodokos, the singer at the court in Phaeacia,

whom, the Muse loved above all other men, and gave him

both good and evil; of his sight she deprived him, but

gave him the sweet gift of song.

(Od. 8.63–65, trans. R. Lattimore)

The prophetic power of the blind is generally considered as a kind of compensation. The great seers like Teiresias and Phineus went blind because they had seen the gods, because they knew too much and revealed their knowledge to men. But blindness is more than a punishment or destiny. It sharpens the other senses, especially the power of memory, and thus for some authors becomes a prerequisite for particular transcendental gifts. According to a saying of the Delphic oracle, memory is "the face of the blind."[19] This apparently reflects a widespread belief. The philosopher Democritus was said to have blinded himself so that his spirit would not be distracted by the outside world.[20] By emphasizing Homer's blindness, the artist celebrates above all a wisdom that derives from unsurpassed powers of memory.

But how should we imagine the lost body that went with this head? The nearly upright position of the head, on which all the best copies agree, suggests a standing rather than a seated figure. Based on the standard iconography of old men in this period, he must have been either leaning on a staff, the attribute of the elderly and especially the blind (Soph. OT 455), or at least holding one in his hand.[21] The Late Antique poet Christodoros, ca. A.D. 500, seems to have seen just such a statue of Homer in the Baths of Zeuxippos in Constantinople:

He stood there in the semblance of an old man, but his old age was sweet, and shed more grace on him. He was endued with a reverend and kind bearing, and majesty shone forth from his form. . . . With both his hands he rested on a staff, even as when alive, and had bent his right ear to listen, it seemed, to Apollo or one of the Muses hard by.

(Anth. Gr. 2.311–49)[22]

A statue of this type is in fact known, though in a version of the fourth century B.C. , from a copy found in the gardens of the Villa dei Papiri, which might allow us to associate the portrait of Homer with a similar body.[23] Unsure of his step because of his blindness, he would have supported himself on the staff and, in so doing, turned his head ever so slightly to the right, away from the viewer. This very expressive turn of the head is well preserved in several of the copies. That is, the poet stands directly facing the viewer and yet remains fixed in his own world.

On the question of who put up the original statue and where, we can only speculate. But as luck would have it, the earliest attested statue of Homer belongs to the same period as our original, and Pausanias, who mentions it in his description of the sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia (5.24.6, 5.26.5), also provides some helpful information on its context. About 460 B.C. Mikythos, a well-known Sicilian statesman who had served as regent for the children of the tyrant Anaxilaos in Rhegion and Messana and subsequently emigrated to Tegea in the Peloponnese, made dedications at Olympia of unheard-of proportions, for the recovery of his son. This included a group of at least twenty statues by the sculptor Dionysios of Argos, displayed at a prominent spot north of the great temple.[24] The poets Homer and Hesiod apparently stood alongside the Olympians and other gods, including Asklepios and Hygieia. Their location by the gods can best be interpreted to mean that Homer and Hesiod are the messengers of the gods, who mediate between them and mankind, a sentiment also expressed in a well-known passage of Herodotos: "It was Homer and Hesiod who created a genealogy for the gods, who gave the gods their epithets, allotted them their honors and responsibilities, and put their mark on their forms" (2.53).

This interpretation is also supported by the fact that Mikythos' dedication included a statue of the mythical singer Orpheus as well. He stood like a prophet beside the statue of his divine patron Dionysus, whose mysteries had been associated with the so-called Orphic Hymns since the sixth century.[25]

Even though our portrait type is certainly not to be identified with the Homer in Mikythos' dedication, which was under-life-size, at

least it provides us some notion of where and in what context a statue of Homer could be set up in the fifth century, that is, in a sanctuary, along with other statues, as part of a dedication that expressed certain concerns and intentions of the dedicator. In the case of Mikythos, his son's illness may not have been the only motive. No doubt this recent émigré to mainland Greece managed to call attention to himself in spectacular fashion by making a dedication of such outsized proportions. The very fact that the two poets were so prominent in the group says something about the importance of such figures in Greek society of the time.

In this connection, the "realism" of the Homer portrait also takes on some significance. He is not like those images of mythical old men in vase painting or even the seer from Olympia, who, despite bald head and white hair, have an ageless and idealized face. Rather, Homer's face is marked by a new kind of physical immediacy, not so much in its individual traits, but as the face of a typical old man who is at the same time an individual, with protruding cheekbones, sharply arched brows, sagging flesh, furrows, and wrinkles. Along with contemporary likenesses of Themistocles and Pindar, he is among the very earliest Greek portraits.[26] This new kind of portraiture brings Homer out of the distant past and into the present.

In this light, we might imagine that such a portrait, especially one displayed in a conspicuous public place like the dedication of Mikythos, was meant as a conservative response to the enlightened criticism of men like Xenophanes, who spoke out not only against the agonistic values of the aristocracy, but against traditional religious piety associated with Homer.[27] In any case, a portrait like this surely implies the recognition accorded the sophia that poets and thinkers had claimed for themselves. In this same period, in Athens, Aeschylus' Eumenides brought him the status of political and religious commentator, even a kind of theologian of the city.[28]

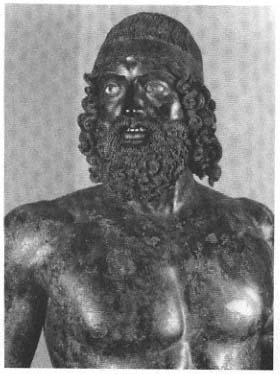

It is astonishing that a society like that of the Greeks in the sixth and fifth centuries, which so glorified youthful vigor, should have accorded the ultimate spiritual and religious authority to the figure of a decrepit old man. We should keep in mind that in a sanctuary like Olympia such a portrait statue would have stood not far from divine and heroic statues like the Riace Bronzes (fig. 11). The juxtaposition

Fig. 11

Bronze statue of a hero found in the sea at

Riace. Greek original ca. 450 B.C. Reggio

Calabria, Museo Nazionale.

of two such antithetical statues must have intensified the contrast, the unbounded glorification of youth and strength in a warrior or athlete set against the wisdom of age and corporeal frailty. The polarity of these images exemplifies the diversity and vitality of Greek culture. Finally, in this Homer are the roots of the extraordinary portraiture of aging philosophers of the Hellenistic period.

The reconstruction of the statue of Homer and its possible context are of course too vague and speculative to be conclusive. The question of where the actual statue stood simply cannot be answered.[29] But this example has at least demonstrated that even a single relatively faithful copy can offer new insights, when we focus on the question of con-

text. And that it is often better to ask unanswerable questions than to ask none at all.

In the Greek imagination, all great intellectuals were old. The portrait of Homer stands at the beginning of a long tradition that reaches to the end of antiquity. There exists no portrait of a truly young poet, and certainly not of a young philosopher.