IV.

In the Shadow of the Ancients

Stand here still and look on Archilochus, the Singer from ancient times [ ton palai poietan].

—Theocritus of Syracuse Anthologia Graeca 5.664

There are fundamental differences between the statue of the comic poet Poseidippus (fig. 75), the last monument we considered in chapter 3, and that of an old lyric poet in Copenhagen (fig. 79). The former is a portrait of a contemporary poet laboring mightily to find just the right words, while the latter is an extraordinary vision of the poetic force embodied in a "singer from ancient times" (ton palai poietan ). The statue of Poseidippus must have been created about the middle of the third century, that of the lyric poet perhaps a half century later. Yet the differences cannot be attributed to changes in style or varieties of sculptural schools alone. Rather, as the Hellenistic period wore on, a gulf arose between the portraiture of contemporary intellectuals and the visual imagery of the great minds of the past. This contrast has barely been recognized in previous scholarship, and I should like to make it the focus of this chapter. Retrospective portraits as such were, of course, nothing new. What, then, is the difference between such imagined portraits of the fifth and fourth centuries as the Anacreon on the Acropolis (fig. 12) or the Sophocles in the Theatre of Dionysus (fig. 25) and works like the singer in Copenhagen? What was the purpose of this new kind of portraiture?

The Old Singer

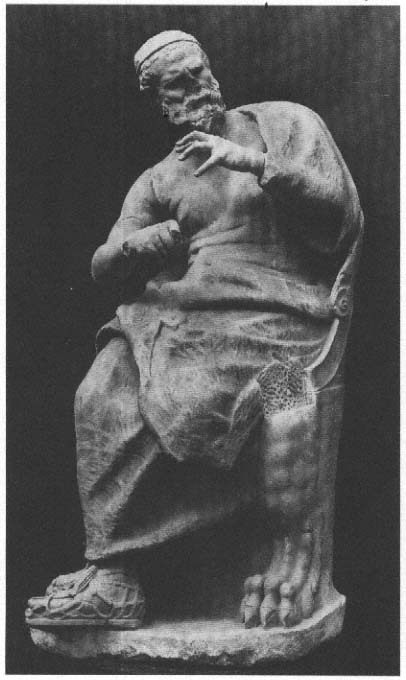

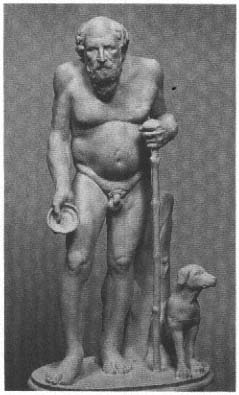

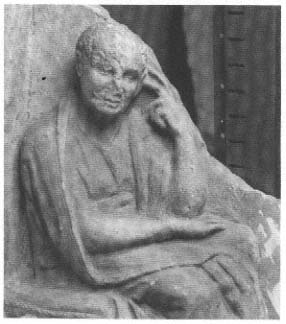

The singer is known from a superb copy of the first century B.C. , almost completely preserved (fig. 79).[1] He held a lyre in his left hand

and the plectrum in the right, just like the statue of Anacreon, which, incidentally was found in the same Roman villa at Rieti. But while the Classical statue's physique and contrapposto stance conform fully to the standard citizen image of the Periclean age, the old singer is presented to us as an awe-inspiring figure from the distant past. He sits on a tall throne with mighty lion-paw feet and has a thick, old-fashioned cloak of matted wool draped about his hips. He wears a luxuriant beard that is utterly different from the contemporary fashion. His powerful build implies that in his youth he was a tough opponent, while the slack limbs and the creases in the chest and belly are striking reminders of his advanced age.

But old age has not stilled the singer's energy and passion. He has sung himself into a state of ecstasy, his entire body seized by the enthusiasm with which he strikes his stringed instrument. His feet are intertwined, as if they had to brace themselves against the surge of energy and prevent the old man from leaping up. The upper body, with the instrument, curves like a spiral to the right, but the head, in its passionate movement, is turned away from the viewer. The singer is completely caught up in his song, enthralled by the instrument and oblivious of the world around him. To judge by the excited expression of his face, the verses he recites have a contentious tone. His inlaid eyes, now gone, must have considerably heightened the pathos of the expression.

A certain identification of the singer is not possible; Pindar and Archilochus have been suggested. What is certain is that the artist meant to represent a specific poet. The detailed characterization presupposes a viewer who was able to infer an association between the portrait and the poetry or the life of the poet. The viewer would have made such observations as these: it must be a lyric poet of the distant past whose work is highly prized in the present, as indicated by the beard, cloak, and throne; this is a poet of strong temperament who sang contentious songs, lived into old age, and had been very strong as a young man. He must have composed not only hymns and battle songs, but also drinking songs for the symposium. The ancient viewer would have inferred this last element from the ivy wreath, a rare attribute, which is preserved in most of the copies (cf. fig. 4).

Fig. 79 a–b

Statue of an old singer. Roman copy of a statue ca. 200 B.C.

Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek. (79a restored).

Of all the renowned Archaic poets, the one who fits this description best is Alcaeus of Lesbos (ca. 600 B.C. ). He himself speaks in one poem of his "greying breast," and we know how passionate and contentious he remained well into old age.[2] The severe and serious Pindar, with his mighty kithara, was imagined very differently in this same period, as we can see in the majestic enthroned statue that stood in an exedra in the sanctuary of Serapis in Memphis.[3] It follows from these observations that we have here most likely a "character portrait" reconstructed from the subject's poetry and what was known of his biography. A retrospective portrait of this kind can have been created only in an environment where there were people familiar with poetic traditions who felt a need for such an image and were able to advise the sculptor accordingly. The statue presupposes a viewer who is also a cultivated reader.

A Peasant-Poet

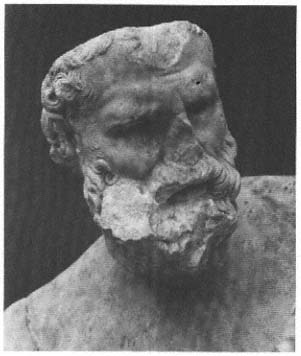

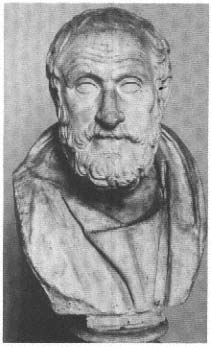

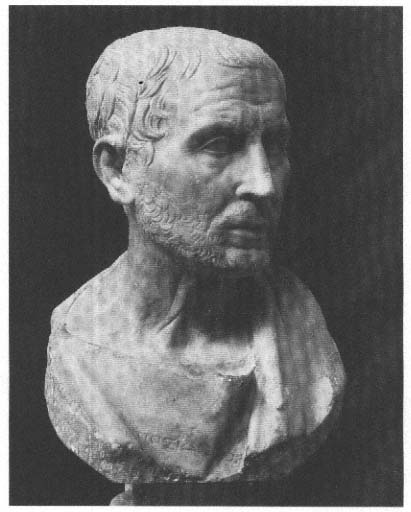

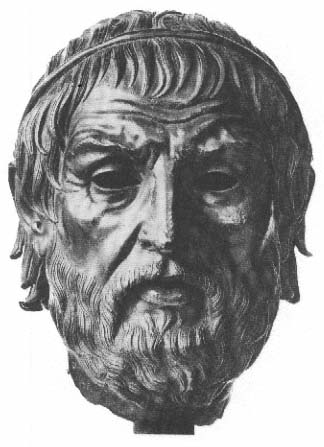

The portrait of the old singer is not a unique phenomenon. There is a whole series of these retrospective images of great men of the past among the Roman copies of Hellenistic intellectual portraits. But unfortunately, as is so often the case, for almost all of them only the head is preserved, thereby severely limiting our ability to interpret them. This is true, for example, of the most problematic case, a portrait that was once taken to be Seneca and has thus acquired in the archaeological literature the rather odd nickname of Pseudo-Seneca. We are fortunate that the superb copy in a bronze bust from the Villa dei Papiri in Herculaneum (fig. 80a–c) gives at least a hint of the body type.[4] The head represents a complete break with the traditional aesthetic of Classical art. Among Hellenistic portraits, apart from the statue of the Cynic in the Capitoline (cf. fig. 72), there is no other even remotely comparable to this one in its unrestrained rendering of passion, old age, and dishevelment. Rather, the closest comparison might be with the roughly contemporary statue of the pitiful old fisherman, which may give us some idea of the realism with which the poet's desiccated body must have been depicted.[5] Peter Paul Rubens already combined the portrait with the fisherman's body, even though he was aware of the head that went with it. If the large number of copies of the Pseudo-Seneca, one of them a double herm together with Menander, did not guarantee that he must represent one of the most famous Greek poets, we might have suspected that the type is not a portrait at all, but rather a genre figure.

The hair falls over the brow in straggly locks. This is not, however, meant to express poetic inspiration or enthusiasm, as in other instances, but evidently the unkempt appearance of the peasant. This is particularly obvious at the nape of the neck, where the locks are caked with dirt and sweat, as well as in the crudely trimmed and irregularly growing beard. This last detail is a clear allusion to the iconography of the peasant, as we have seen in our discussion of the portrait of Chrysippus (p. 112). In pseudo-Aristotelian physiognomic theory, peasants and fishermen were marked by their irregular beards (along with other negative traits) as ridiculous and even as morally inferior beings. In the

bronze bust of the Pseudo-Seneca, this trait is only hinted at, but enough to evoke the imagery of fishermen and peasants, with their negative connotations, when contrasted with the beards of contemporary philosopher portraits (excepting Chrysippus, of course). This impression is reinforced by the leathery skin, dried out by the sun, forming ugly furrows on the neck and shoulder, as well as by the shriveled body with bones protruding in face and neck.

But this old man is in no way characterized as sick or dispirited. Instead, he is filled with a passionate energy. The tension in the forehead and eyebrows suggests extreme concentration, as he searches for just the right word. There is something compelling in his expression, as if he just has to express himself, as if something is driving him that is stronger than he is. But who would listen to this unkempt old man, an outsider in polite society?

As in the case of the seated singer, this portrait seems to aim at capturing a specific set of biographical data, at rendering in its particular pathos a specific and unmistakable spiritual physiognomy comprising these elements: manual labor, poverty, a disregard for personal appearance, and a breathless, almost fanatical manner of speech. All this seems to point to the peasant-poet Hesiod, who was called to poetry by the Muses while he was tending his goats on Mount Helikon and who lived and, in his verses, described a life of inexorable toil, worry, and disappointment. That later ages did indeed imagine Hesiod as an old man is confirmed by Vergil, who evokes him as the "old man from Ascra" (Ecl. 6.70: Ascreus senex ).

But I am less concerned here with the identification of the portrait, which must remain a conjecture until an inscribed copy is discovered, than with the boldly rendered "biographical physiognomy" of this old man. One of the great poets of the past is presented with the physiognomic traits of the peasants and fishermen who had always been despised by bourgeois society and had to struggle to eke out a living. This is more than just a retrospective, literary portrait of a poet. Rather, like the silen's mask of Socrates and, later, the portrait of Chrysippus, it is a polemical statement of the independence of intellectual talent from noble birth or societal convention. Even a man who stood on the margins of society, who did not have the benefits of paideia, could

Fig. 80 a–c

Hesiod (?). Augustan bronze bust after an original ca. 200 B.C. Naples,

Museo Nazionale.

become a great poet. And again, a body worn out by toil and privation could still harbor a great spirit. Neither humble birth nor manual labor could rob this man of the power of the poetic word. An image like this implies a fundamental challenge to prevailing norms and values, even if only retrojected into the distant past. We shall return to this point presently.

Invented Faces

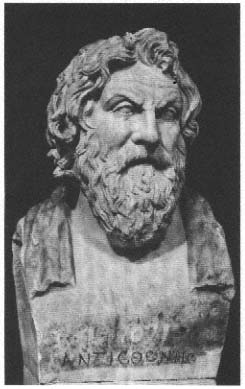

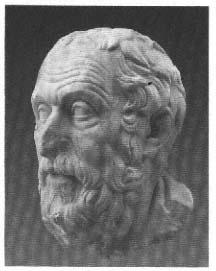

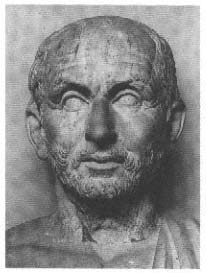

Hellenistic artists, confronted with the new task of creating retrospective literary portraits, must have developed an astonishing range of subtly differentiated types. Although we are mainly dependent on bust and herm copies often of dubious quality, the varied facial expressions of these portraits alone illustrate how the sculptors strived to translate each subject's intellectual, personal, and biographical traits into a "spiritual physiognomy." A few specific examples may make this clear. I have chosen four retrospective portraits that represent different kinds of intellectuals, two poets and two philosophers or scholars, all of them derived from prototypes that can be dated by stylistic criteria to the Middle Hellenistic period, that is, the years ca. 220 to 150 B.C.

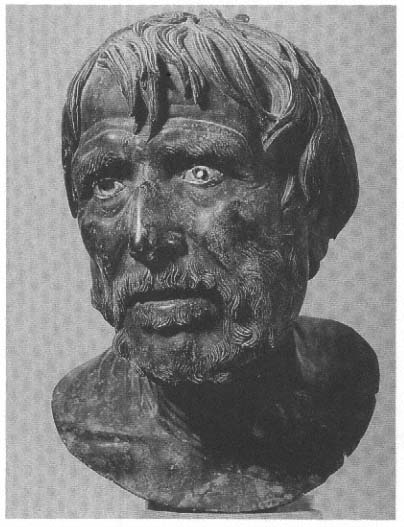

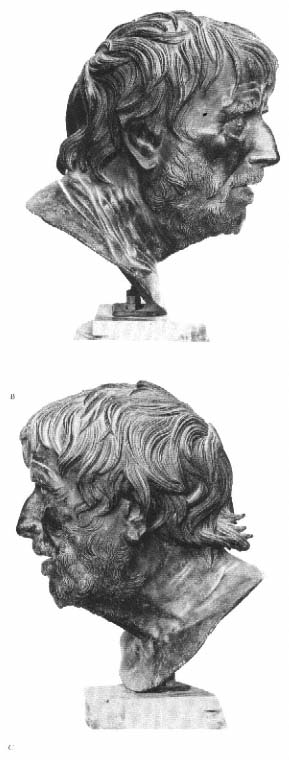

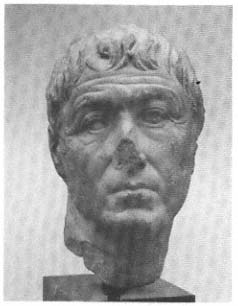

A portrait from the Villa del Papiri is identified by a painted inscription as that of the epic poet Panyassis of Halicarnassus (fig. 81).[6] He was said to have been put to death by the tyrant Lygdamos about 450 and was the author of a Herakles epic that was highly esteemed by Hellenistic philologists and poets. His countenance is tense, almost suffering, the expression quite different, say, from that of a grim old man whose wreath has been thought to mark him as a poet as well (fig. 82), even though both heads show a comparable contraction of the forehead. The piercing look of the latter poet and "the expression of a decrepit and ugly face, filled with hate and sarcastic bile," have suggested the name of Hipponax, the sixth-century poet known for his vicious invective verse.[7]

Equally striking is the contrast between Panyassis' facial expression and the expression of detached observation in the face of a portrait that has, on convincing grounds, been taken as that of the most

Fig. 81

Portrait of the epic poet Panyassis (died ca.

mid-fifth century B.C. ), after an original of the High

Hellenistic period. Naples, Museo Nazionale.

Fig. 82

So-called Hipponax. Hellenistic

original of the second century B.C.

Athens, National Museum.

famous physician of antiquity, Hippocrates of Cos (fig. 83). The seated statue from which this head derives depicted the old man with what must have been his characteristic inclination of the head, and therefore probably with the body tensed as well.[8] The calm objectivity of the so-called Hippocrates is in turn utterly different from the severe and penetrating, almost fanatical intensity of a portrait for which a relief in the Terme Museum has recently suggested an identification as the pre-Socratic philosopher Anaximander (fig. 84).[9]

My deliberately subjective readings of these portraits, based on gut feeling and psychologizing interpretation, are of course not binding but only meant to provoke a response. And even if my reactions are not at all those intended by the artists, the important thing is the phenomenon itself, a completely different conception of the notion of portraiture. No longer, as in the retrospective portraits of the fifth

Fig. 83

Hippocrates. Bust from the grave of

a physician, after an original of the High

Hellenistic period. Ostia Museum.

Fig. 84

Portrait of the pre-Socratic philosopher

Anaximander (?). Roman copy of a Hellenistic

original. Rome, Capitoline Museum.

and fourth centuries, is the goal a paradigmatic display of virtues accepted by the entire society and thereby a didactic and hortatory effect. On the contrary, these new retrospective creations, with their vivid expressions, would be unthinkable in the context of publicly displayed monuments in the Hellenistic cities, as honorific or votive statues. Those statues as a rule continued the fourth-century traditions of the garment correctly draped about the body and the controlled pose based on Classical draped figures. Their expressions may have occasionally conveyed a sense of energy or contemplation, but violent or dramatic elements were avoided (pp. 188f.).[10]

For these portraits striving to capture a literary image, in contrast, there was obviously no need to adhere to such conventions, since the subjects belonged in any case to the far-distant past. Thus in their dress, in their physical characteristics, in the language of gesture and

facial expression, they stand intentionally apart from contemporary conventions of the citizen image. This separation in turn implies that these portraits must have fulfilled new and different functions.

As we have noted, the retrospective portraits presuppose an educated viewer, who would understand the biographical and literary allusions, who was familiar with the literary judgments and characterizations applied to each figure, and who might even have taken part in the ongoing discussion of the great thinkers of the past. It seems only reasonable to associate the origins of this new kind of portraiture with the rise of Hellenistic philology and of the new breed of scholar who flourished in particular at the royal courts.[11] The Museum in Alexandria, founded by Ptolemy I, in whose library "the king had assembled the writings of all mankind, all those that deserved serious attention" (Eus. Hist. eccl. 5.8.11), became a model, and not just for other rulers. The great philosophical schools and gymnasia in Greek cities began to collect the writings of earlier authors, since the reading and interpretation of texts had become the focal point of a new form of education that gradually engaged the whole of Hellenistic society. From the beginning, Alexandrian scholars were conscious of a sharp break between past and present. The writers of the past belonged to a glorious but remote epoch, and their writings were a precious legacy that had to be conserved and used as a source of wisdom and guidance. Contemporary poetry belonged to a different genre that could not be compared to that of the past. This is the same gulf that separates the portrait statues of a Menander or Poseidippus from those of the old singer or the so-called Hesiod.

The professional scholar and poeta doctus under royal patronage was a new breed of intellectual, living in splendid isolation from urban society, freed from the normal citizen responsibilities and able to devote himself fully to his scholarly work. "The melting pot of Egypt nourishes many men, bookish scribblers forever quarreling in the bird cage of the Muses": thus the sharp-tongued Skeptic Timon of Phlius (frag. 12 Diels), who passes judgment from the perspective of an intellectual still fully integrated in the society of the polis. But it was this very isolation, the clustering of scholars in academies and philosophical cliques, that gave rise to a new pursuit, the study of earlier writers as a purely literary and aesthetic pastime, along with an interest in every biographical an-

ecdote, the same interest we see informing the retrospective portraits. If we wish to gain some idea of the range of associations that the ancient viewer might have made, we might take a brief look at two literary genres of the period, the bioi, originating mainly in the tradition of the Aristotelian school, and the epigrams on poets. It may be no accident that, in just the period when the retrospective portrait was at its height, the late third and early second centuries, we hear of a writer of bioi named Satyros. Fragments of his Life of Euripides survive, and they betray an intention to demonstrate, in Ulrich von Wilamowitz's words, "die Harmonie zwischen Wesen, Leben, und Dichtung." Satyros' reconstruction of Euripides' life is derived mainly from the poet's work, and this is just how we must suppose the sculptor (or his adviser) proceeded. Biography and portrait, both inspired by the new philological bent, had the same goal: to gather impressions from the great man's work and then translate these into a specific image, a uniquely individual presence. But while the intellectual level of most of the bioi, as they are known to us, is rather modest, the portraiture—to judge from certain Roman copies—must have included some true masterpieces. Satyros, incidentally, is known to have written lives not only of poets, but of great men of all sorts, including Alcibiades, Philip of Macedon, and even philosophers such as Diogenes.[12] We may therefore assume that the retrospective portrait statues also included philosophers, statesmen, and other historical worthies.

Even more informative, and certainly more enjoyable to read, are some of the more artful epigrams. These imagine the reader at the tomb or even before a statue of one of the poets of old and try to evoke reminiscences of his life and work. The process of idealization goes together with a distancing of the reader's present from the "once upon a time" of the past.[13]

The Cult of Poets

Though literary and intellectual in conception, these retrospective portraits, in the purposes they served, went far beyond the interests of a small circle of scholars. The reading and interpretation of literary masters was not restricted to the "bird cages" at the royal courts. The

great library at Alexandria itself was open to all who wished to study and read. Indeed, the preoccupation with literature seems to have become a kind of all-embracing social dialogue in Hellenistic Greek cities of the third and second centuries. While the youth were educated in the classics and made to learn them by heart, their elders would congregate at the gymnasia to hear an itinerant scholar, poet, or philosopher, or other speakers employed by the city. These public lectures often focused on the interpretation of great writers of the past. In this way, the poets of old and the philosophers were elevated to the status of authorities who provided guidance in all of life's important matters. Cities would institute genuine hero cults for their own intellectual heroes, complete with appropriate sacrificial rituals. The establishment of such cults is in itself of less interest for us (kings and benefactors also enjoyed this highest form of public honor) than the artistic elaboration that they occasioned and inspired.

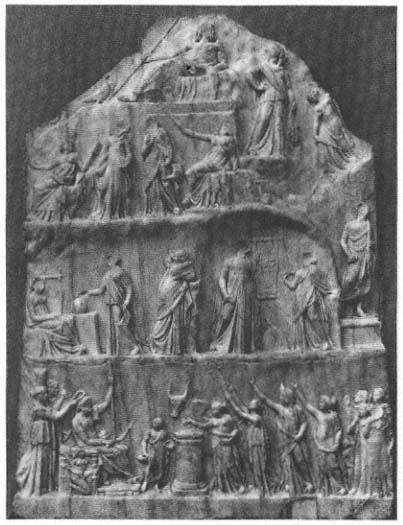

At the very top of the hierarchy, of course, stood Homer, the font of all wisdom, religion, and culture. The relief of the sculptor Archelaos of Priene (fig. 85a, b) translates into visual terms a complete vision of Homer as the ancestor of Hellenic culture.[14] The monument was probably the votive relief of a contemporary poet who had won a tripod in a poetic contest (perhaps in honor of Homer himself) and dedicated it, along with a statue of himself, to Apollo and the Muses. His simple draped statue stands at the right, just at the foot of the hill of the Muses. Below, we are looking into a sanctuary of Homer. He is enthroned, like Zeus, a tall scepter in his right hand and a book roll in the left, while the personifications of the various literary genres, arranged in a careful hierarchy (Historia, Poiesis, Tragodia, Komodia), sacrifice a bull in his honor. The sacrificial attendant is a boy called Mythos. The master's twin works, Iliad and Odyssey, kneel beside the throne. In front of the footstool, two mice nibble on a roll, probably an allusion to the Batrachomyomachia, which was then considered a genuine work of Homer. From behind the throne, the standing figures of Chronos and Oikoumene crown the poet.

Unlike the other figures, these two bear unmistakable portrait features, probably a discreet homage to a royal couple whom we can no longer identify. They may have been responsible for the splendid Homereion depicted here or another one like it. Four female figures

Fig. 85 a

Votive relief of a poet in honor of Homer, by the sculptor Archelaos

of Priene. Ca. 150 B.C. London, British Museum.

on a smaller scale watch the sacrifice from a corner: Arete and Mneme (Memory), with their younger sisters Pistis (Faith) and Sophia. A little girl, Physis, turns to Pistis with a look of supplication and tugs at the hem of her sister, who bids her be silent.

The whole is an extravagant panegyric, celebrating the central im-

Fig. 85b

Detail of an etching. From Ex calcographia Domenici de Rubeis (Rome, 1693).

portance of Homer and, through him, of literature and poetry in education. Particularly striking is the great value attached to certain skills. Among all the Muses, their mother, Mnemosyne, is singled out and stands closest to Zeus. The message of this relief is clear: the standards for the education of the young must be derived from the great literary works of the past, for these are the source of cultural memory. But those writers themselves are all nourished by a single source, Homer. This is truly an image to warm the heart of a classical philologist.

The Archelaos Relief not only presents us with an all-encompassing vision of learning but also gives some idea of how statues of Homer may have been set up in the numerous sanctuaries of the poet in Hellenistic cities that are attested in the literary sources. The Homereion in Alexandria is described as follows by Aelian: "Ptolemy Philopator erected a temple to Homer and placed within it a magnificent seated statue of the poet and, in a semicircle around him, all the cities that laid claim to Homer" (VH 13.22). We may suppose that these various cities, personified in statues in the Homereion at Alexandria, also had richly outfitted sanctuaries of Homer. One that is well attested was in Smyrna, where Strabo saw a temple with cult statue (xoanon ), surrounded by columned porticoes. His use of the word xoanon implies a particularly ancient-looking cult statue, perhaps of wood. This was no doubt intended to legitimize the city's claim to being Homer's birth-

place. "The people of Smyrna have a special claim to Homer, and they even call a bronze coin the Homereion," observed Strabo (10.1.37). But cities of the Greek mainland also accorded the father of poets cultic honors. We hear, for example, of sacrifices conducted by the Argives at a bronze statue of Homer (Cert. Hom. et Hes. 18).

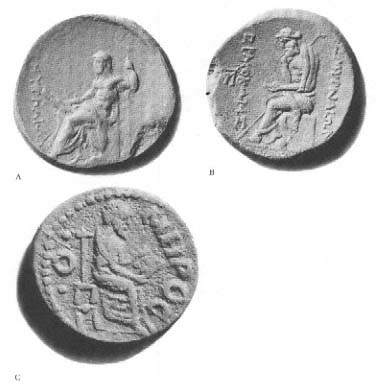

In addition to Homer, many other intellectual heroes enjoyed cult worship. In Priene, for example, stood a heroon of Bias, who had for centuries been numbered among the Seven Wise Men. This small city even issued silver coins about the middle of the second century B.C. with a full-length figure of Bias, probably a rendering of the statue that stood in the "Bianteion" (fig. 86b). The coin depicts a tripod alongside the statue, an allusion to an often-told story. One day in Priene, some people found a golden tripod at the shore bearing the inscription "For the wisest." The city awarded the tripod to Bias, but he in turn, in pious modesty, dedicated it to Apollo (D. L. 1.82).[15] We see here how such a heroon attracted cult legends, just as did the sanctuaries of the traditional gods and heroes, and how cities would strive to propagate these legends, like that of Bias' tripod, throughout the Greek world.

The Archilocheion on Paros, which probably dated back to the Archaic period, was, like other heroa, associated with the poet's grave and a gymnasium.[16] In the third century, a Parian named Mnesiepes ("Collector of Epics") had a temple in honor of Archilochus either built or renovated, by order of the Delphic oracle. A long, partially preserved inscription tells legends from the life of the poet that the dedicator claims to have collected from ancient tales. In reality these stories are paraphrases of Archilochus' poetry, including the story, modeled on Hesiod, of how he was called by the Muses, who made him a gift of a lyre as he was driving a cow to market. A later inscription, of the first century B.C. , contains a list of the poet's writings and deeds in chronological order.

These dedications, with their detailed reports of the life and work of Archilochus, "testify to the poet's continued importance to the people of Paros, who would visit the shrine and read the inscriptions. It is significant that what interested them about Archilochus was not so much his poetry as the relationship of his poetry to his life."[17] In this instance, the sanction of Delphi was particularly important, not only for the cult on Paros, but for its fame beyond the island. Paros

Fig. 86 a–d

Four Hellenistic coins of Greek cities, representing local intellectual heroes

of the past: a, Archilochus of Paros: b, Bias of Priene; c, Anaxagoras of

Clazomenae; d, Stesichorus of Himera (photos enlarged).

issued coins in the first century B.C. with a portrait of the poet as a youthful figure nude to the waist, holding a lyre in his left hand and a book roll in the right (fig. 86a).[18] His one-time reputation for slander and dubious citizen conduct was long forgotten, and all that remained was his fame as a great poet.

There were other cities as well that were putting their intellectual heroes on coins by the second and first centuries B.C. Clazomenae, for

Fig. 87

Homer. Coin from the island of Ios (3:1). Berlin,

Staatliche Münzsammlung.

example, minted coins showing the philosopher Anaxagoras (fig. 86c), and Sicilian Himera the poet Stesichorus (fig. 86d), both represented as vigorously active figures. Stesichorus sings and plays a stringed instrument, while Anaxagoras is shown as a teacher, in the same pose as Hermarchus. The majority of such coins, however, appear first under the Roman Empire. Yet such early examples as those just mentioned suggest how important these figures were to the Greek cities already in the Hellenistic period, both for their image of themselves and for their understanding of their own traditions.[19]

Most numerous, however, are the coin portraits of Homer,[20] minted in several of the cities of Asia Minor. The little island of Ios, for example, which claimed to possess the tomb of Homer, had already in the fourth century B.C. circulated splendid silver coins with a head of Homer that, without the inscription, could easily be mistaken for an image of Zeus with flowing locks (fig. 87). The die cutter probably did in fact simply use a Zeus type with which he was already familiar. We see from this how early Homer was turned into a mythical figure, and how the assimilation of his image to that of Zeus derived from an earlier notion of Homer's unique significance. The figure of the singer is assimilated to that of the gods and heroes of whom he sang.

Fig. 88 a–c

Homer on coins of the cities of Smyrna (a–b ) and Chios (c ).

The city of Smyrna minted several different portrait types, starting in the first half of the second century B.C. , some of them simultaneously. Not all of these images could be based on existing statues, much less "cult statues." This variety shows clearly the intense fascination of Homer in this period, how the popular imagination constantly reshaped his image, while at the same time imagery of the Olympian gods could only imitate fixed Archaic and Classical prototypes. The most popular coin type of Homer in Smyrna shows a Zeus-like enthroned figure, as on the Archelaos Relief, holding a scepter and (in place of the thunderbolt!) a book roll. In one of the earliest issues, he is even more closely assimilated to Zeus, with bare chest and the right hand, with the book roll, outstretched in a commanding gesture (fig. 88a). At the same time, however, beginning in the decade 180

to 170, Smyrna also issued a contemplative Homer, with the head propped on one hand (fig. 88b). Later came other images, the poet reciting dramatically from his work and, on nearby Chios, the poet quietly reading in his Iliad (fig. 88c). This incongruous notion of the quietly reading Homer was also a Hellenistic innovation, in some other medium (cf. fig. 104). The activities of Homeric scholars and connoisseurs are, as it were, retrojected onto the poet himself. The act of reading, of meditating on and immersing oneself in his verse, acquires an almost religious aura.

The Divine Homer

There can be little doubt that one's expectations and attitude toward such a statue as that of Homer on the Archelaos Relief, almost more of a cult image, are quite different from how one might approach the traditional honorific statue for a poet or philosopher. The ancient viewer was invited to discern and reflect upon the biographical and literary elements present in the image, to meditate piously upon them in the spiritual setting of a shrine. It was this aura of the sublime that was evidently the very effect aimed at in a number of the retrospective portraits.

It is this particular aspect I should like to focus on in considering the famous portrait of the blind Homer.[21] Again we have copies of only the head, but some idea of the body may be supplied by the Archelaos Relief and the coin types (figs. 85, 86) that depict Homer as extremely old and blind. The tradition of Homer's blindness is an old one, as we have seen, perhaps derived originally from the blind singer Demodokos in the Odyssey . In any case, it is certainly present in the well-known portrait of the elderly Homer created about 460, with which we have dealt in chapter 1 (fig. 9). The blind Homer was, nevertheless, always only one of several ways of portraying the poet, as the other versions on coins attest. But whereas the early portrait, created at the time of the "Severe Style," conveys a sense of profound calm, the Hellenistic sculptor has rendered his vision of Homer in highly dramatic terms (fig. 89). If the earlier portrait merely hinted at the

Fig. 89

Homer. Roman copy of a High Hellenistic statue ca. 200 B.C. Boston,

Museum of Fine Arts.

blindness in the closed eyes, here it is rendered with almost clinical accuracy, with the eves half-closed and the muscle degeneration around them. And if the early portrait presented a figure that, for all its loftiness, might still be likened to images of contemporary older men, this is now out of the question. The Hellenistic portrait belongs to another category. The heavy, archaizing locks framing the face, the fillet containing the hair rolled up in the back—also an archaizing trait—and the full, heavy beard all conjure up the majestic aura of a god.

The deep-set, lifeless eyes and the whole expression of the facial features are in certain ways rendered very variously by the Roman copyists. As in the case of Menander, it seems to me hardly possible to reconstruct an authentic version of the prototype out of the more than twenty-five surviving copies. Once again it is precisely the copies of highest quality that may turn out to be instead interpretations of the original, pursuing their own interests and intentions. Roughly speaking, the copies may be divided into two groups. Some sculptors emphasize the active features of the face, others the passive. One group of copies emphasizes the intricate forms of the coiffure, especially the archaizing rounded locks at the temples, while the other confuses these, sometimes in an apparently intentional attempt to render a wild and unkempt mass of hair. We may best illustrate the difference in a juxtaposition of two of the most impressive copies, though bearing in mind that because the two are so outstanding in workmanship, they will have absorbed much of the Roman taste of the period in which they were carved.

A head in Boston, probably of Flavian date, stresses more the active features (fig. 89).[22] Brows and forehead are overlaid with little rippling muscles that seem to be in continual irregular motion. Our impression is of a fervid imagination in high gear, and we barely notice the elements of decrepit old age. In the famous head in Naples, on the other hand, a Late Antonine copy, the dominant impression is of the frailty of old age (fig. 90).[23] The visionary aspect is linked to a sense of agonizing struggle. The forehead is almost painfully drawn up, and the eyes and face have a kind of dead look. It was this head that the young

Fig. 90

Homer. Roman copy of the second century A.D. after the same

statue as fig. 89. Naples, Museo Nazionale.

Goethe had in mind in his impassioned description for Lavater's Physiognomische Fragmente:

I enter the presence of this figure uninformed. I say to myself: the man sees nothing, hears nothing, doesn't move, doesn't react. In this head, the midpoint of all the senses is in the high, gently arching hollow of the brow, the seat of memory. Every image is stored here; all the muscles rise up, to conduct the figures of the living down to the cheeks that will give them voice. . . . This sunken blindness, the vision turned inwards, energizes his inner life all the more, and makes the father of poets complete. These cheeks have been molded by never-ending speech, these muscles of speech the well-worn paths down which gods and heroes have made their way to mankind; the willing mouth, only the gateway to such images, seems to babble like a child's, has all the naïveté of youthful innocence; and the enclosure of hair and beard contains and ennobles the breadth of the head.[24]

In the Boston head, in contrast, the power of the will wins out, especially in the mouth and eyes: the mouth holds firm, trying to shape into words the vision of the mind's eye. Even if none of the copies can be proved to be the most "reliable," we must nevertheless once again assume that the original somehow combined the different and sometimes contradictory traits captured in the varying interpretations of the copyists: physical frailty and extreme old age, on the one hand; a god-like loftiness and dazzling inspiration, on the other. The head in Boston and others of its type, with the complicated treatment of the hair and facial features, come closer, in my view, to the High Hellenistic original than the group to which the head in Naples belongs. One could imagine the Boston head joined to an imposing seated statue of the type on the Archelaos Relief, but not the head in Naples. Perhaps the High Hellenistic prototype was adapted by a Late Hellenistic sculptor who stressed such elements as the frailty of age and the unkempt hair and beard of the old man. But since these later copies do not share any features that clearly distinguish them typologically from the version to which the Boston head belongs, it is probably more likely that the Naples head and others like it are independent

variants whose only common element is a reflection of the style of the Antonine period.[25]

Nevertheless, the important point for our interest is that the reinterpretation of Homer's face continued uninterrupted into the Imperial period and that the copyists were neither able nor willing to conceal their own conceptions of the great poet. We should also remember that the Roman patron had, at least theoretically, not only a choice among the different versions of this particular type, but a choice of several types as well. (In addition to the two versions of the blind Homer just discussed, there was yet another popular type, probably Late Classical in origin, showing Homer with the wide-open eyes of the seer and long hair at the nape of the neck, the so-called Apollonios type.) The various portraits, with their diverse emphases, were of course meant to evoke in the viewer a whole range of associations. Alongside the enthroned prince of poets, the seer heralding the gods and heroes, there may be another conception, exemplified by the pseudo-Herodotean bios, of Homer as a poor singer wandering from city to city. This image, however, first became widespread only in Imperial times.[26] It could be the inspiration for the head in Naples and others like it.

Hellenistic Kings and Archaic Poets

The presentation of this type of literary portrait as a kind of cult image, on the one hand, and the more detailed, biographical approach that appealed to the viewer's own literary training, on the other, are not mutually exclusive. Rather, the spiritual aura only intensified the appreciation of the portrait as a work of art and erudition. Generally speaking, in Hellenistic art the object was expected to offer a whole spectrum of associations. This is why, for example, among freestanding sculpture in the round, it was the statue groups that were particularly popular. A multiplicity of figures allowed the message to be enriched with several layers of meaning, and the Hellenistic world, as the inscriptions also reveal, was an extraordinarily communicative place.

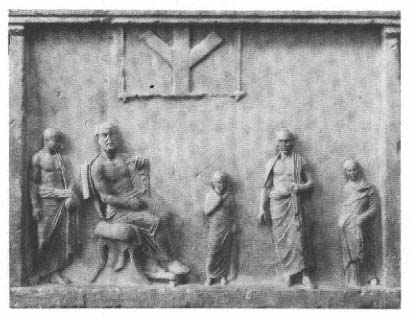

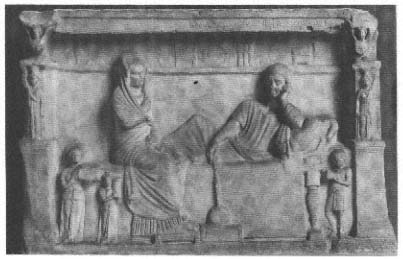

Fig. 91

Exedra with portraits of famous poets and philosophers. Third century B.C.

Memphis, Serapeion.

In the area of literary portraiture as well, the statue group seems to have been of central importance.

We have already seen one example of a meaningful grouping of figures, replete with learned allusions, on the Archelaos Relief. A group of famous poets, original works most likely of the later third or early second century, has been found in the sanctuary of Serapis at Memphis (fig. 91).[27] Twelve over-life-size statues of "ancient" poets and thinkers were arranged here in a semicircle around the seated figure of Homer. Their display, however, represents a renovation of the monument in late antiquity. Once again, the sculptor seems to have used innovative physiognomic characterization to differentiate the various literary genres.

The exedra was placed for maximum effect at the egress of a grand processional street. In earlier times, such an ambitious group would have been conceivable only for mythological heroes or as a gallery of ancestor portraits of a royal house. Astonishingly, among the fragments found at Memphis were two fragmentary heads wearing the royal diadem, one of them a youth. Apparently members of the ruler family responsible for the monument were also depicted among or alongside their intellectual heroes. In other words, the intellectual giants of the past would have been presented as good counselors to the king, as the source of his wisdom and authority. Beyond the immediate historical

or political circumstances, this is clearly a celebration of universal learning as a quality of the good ruler. The cult of learning that manifested itself in the hero shrines of Hellenistic cities finds a close parallel in the public image cultivated by the Ptolemaic kings.

The meagre state of the surviving evidence does not allow us, unfortunately to reconstruct the manner in which retrospective portraits were displayed in other contexts, such as the urban heroon, like the Archilocheion on Paros, or the gymnasia. We may suppose, however, that the association of local literary heroes with their native city would most likely have provided the backdrop for the display of the corresponding portraits, and that cult legends of the type we have preserved for Bias and Archilochus played a central role in this context as well.

The Retrospective Philosopher Portrait: Socrates, Antisthenes, and Diogenes

Another, even more particular function of the retrospective portrait can be inferred from some of the philosopher statues. A Middle or Late Hellenistic Socrates is perhaps the most fascinating of the new interpretations of older philosopher portraits (fig. 92).[28] The artist incorporates elements of both fourth-century portrait types (cf. figs. 21, 35) but creates a new interpretation of the silen's mask. It is for him no longer a metaphor for wisdom, but simply a formula to express extreme ugliness. This new Socrates also has a hideously broad and unattractively shaped nose, a completely bald pate, and sunken cheeks, all of which bespeak an individualized physiognomy. Yet at the same time he is characterized as a mighty thinker in the powerfully arching cranium.

The combination of the dramatically tensed brow and the dignified locks of the archaizing beard with the ugly little pug nose has an almost comic effect for the modern viewer. Socrates has been turned into an intellectual pioneer in the Stoic mold, recalling the mighty strain in the face of a Zeno or Chrysippus (figs. 53, 55). One might easily imagine the commission for this image coming from a Stoic school that wanted to honor its spiritual ancestor with a monument that captured

Fig. 92

Socrates. Roman copy of a Hellenistic

statue. Rome, Villa Albani.

his mental powers in a compelling and contemporary fashion, unlike the Classical portrait type. This vision would of course have been completed with an appropriate body, most likely seated in a vigorous pose of cogitating or instructing. There are several types of seated figures of Socrates that survive in various media, but unfortunately none can be associated with certainty with the type of the portrait head in the Villa Albani.[29]

A similar situation might obtain for the impressive portrait of Socrates' pupil Antisthenes, who was revered as a spiritual ancestor by both Cynics and Stoics (fig. 93). The dating of the portrait type, which is preserved in an inscribed herm copy, has been an unusually thorny problem for scholars.[30] The basic iconographical type is that of the

Fig. 93

Antisthenes (ca. 450–370). Herm copy of a

Hellenistic portrait. Rome, Vatican Museums.

Classical old man of fourth-century grave stelai, with long and sometimes disorderly hair, but here combined with a dramatically rendered brow of the deep thinker, an element that does not occur in Classical portraits. There are physiognomic traits as well, which seem to be linked to the character and intellectual qualities of this particular thinker. All this suggests that the type belongs to that of the retrospective portraits, which in turn supports a dating first suggested long ago, in the early second century B.C.

A clue to the interpretation of the head is suggested by the striking

contrast between the carefully tended beard and the vigorous movement of the long and uncombed hair, something unique to this head among philosopher portraits. The contrast seems to be deliberate, and beard and hair may not necessarily convey the same message. The locks rising from above the forehead had been a popular symbol of strength and energy ever since the portraits of Alexander the Great; and centaurs, silens, and giants were all characterized as "wild" creatures by a similar treatment of the hair. It is tempting to see here a reference, again recalling the bioi, to Antisthenes' vigorous and abrasively contentious character or to his much-admired moral rigor. We may even remember how the chauvinistic Athenians never forgot Antisthenes' half-barbarian origins as the son of a Thracian mother. It is quite conceivable that such a reference could be intended in a biographical portrait of this type; Diogenes Laertius' biography, at least, begins with a mention of this circumstance of the philosopher's birth.

The vigorous movement of the forehead, the eyebrows raised with an almost ferocious intensity, proclaim the intellectual energy of this toothless old man. The well-tended beard, on the other hand, may be interpreted simply as a classical "philosopher's beard," if the second-century date is correct. That is, the beard was meant to label him as "one of the philosophers of old." This handsome and old-fashioned beard balances the individualized characterization embodied in the widly unkempt hair and underlines the seriousness of Antisthenes' philosophy, irrespective of his "character." The pose of the head and the bunching of the drapery at the back of the neck suggest a seated statue. He was evidently depicted as a teacher, unlike the Cynic in the Capitoline (fig. 72). Nor does Antisthenes betray any other Cynic features, and the portrait was surely not conceived as that of the founder of this philosophical "sect." We could, however, imagine a Stoic context for this portrait, as for the Hellenistic Socrates.[31]

The well-known statuette of Diogenes may also be best interpreted within the framework of specific biographical and philosophical/didactic interests (fig. 94).[32] The completely naked body is unique in the iconography of Greek philosophers and might lead one to wonder if this could be an innovation of the Imperial period, reflecting the

Fig. 94

Diogenes (414–323). Statuette of the Imperial

period after a Hellenistic original. H: 54.6 cm.

Rome, Villa Albani. (Cast.)

popular mockery of the philosopher or an interest in the purely anecdotal. On the other hand, the keenly observed realism, especially in the startlingly misshapen and ugly body, is in the direct tradition of works of the third century B.C.

A tired old man, he walks slowly, bent over a staff that he holds in his left hand. The right hand was probably outstretched and might well have made a gesture of begging, as in the eighteenth-century restoration. The body is stiff and ungainly; neither standing still nor moving is easy for the old man. The sagging belly shows that this old man, who

had nothing but contempt for exercise and training in the gymnasium, never did anything to stave off the outward signs of aging. Yet his begging managed to keep him well fed, and the contrast with, say, the emaciated "Old Fisherman" (fig. 61) is obvious. Though these traits could be taken in the anecdotal spirit of later Roman mockery of the intellectual, the impressive bald head of the philosopher, the thoughtful expression, and long, dignified beard (best preserved in the copy in Aix-en-Provence) nevertheless suggest that this Diogenes and his teachings are to be taken seriously. This is surely not the kind of head one would have expected to go with this body, but the sculptor knew what he was doing in this striking contrast.

Once again the ruthless depiction of a decrepit body must be understood in the context of contemporary negatively charged imagery of fishermen and peasants. But, as in the case of the supposed Cynic in the Capitoline (fig. 72) and the Pseudo-Seneca, our reaction is meant to be one of admiration. Diogenes taught his pupils to despise societal convention, including the care of the body, and to renounce all material possessions as a prerequisite to a true independence and spiritual freedom. The naked body is evidently meant to express visually the uncompromising way of life and defiant protest of the founder of the Cynics, truly philosophy in action.

Whereas the realistic appearance of the Cynic in the Capitoline reminds the viewer of the appalling and irritating public behavior of such men and thus presupposes one's experience of them, Diogenes' nudity has a very different significance. Even though the depiction of the body is highly realistic, the figure does not represent an actual encounter. The artist is not striving for the directly provocative effect of the Capitoline Cynic. Even the Cynics did not really walk naked through the streets but wore the tribon made of coarse material (D. L. 6.22). The nudity has rather a didactic meaning and embodies a moral challenge. The sculptor assumes a familiarity with Cynic writings on the part of the viewer, and the statue calls these teachings to mind and "preaches" them, as Diogenes himself once did by means of his appearance: freedom from want and contempt for the body, for physical beauty and bourgeois conventions. Our encounter with the naked Diogenes is, as it were, literary; it takes place not in public, but at home or in

the philosophical school, which is to say in our head. When later Roman writers speak of the nudi cynici (Juv. 14.309; Sen. Ben. 5.4.3), they have in mind just such a portrait.

The iconography of the head, on the other hand, stands in the tradition of Late Classical portrait types, as does that of Antisthenes. Some scholars have even thought they detected similarities to the portrait of Socrates, which escape me.[33] We may once again suspect that the commission for the original came from the Hellenistic Stoics, who are known to have been the first to collect anecdotes about Diogenes.

In spite of his promotion to the status of a serious philosopher, this Diogenes has nothing to do with the popular hero of the Enlightenment, going about with his lantern and searching for the truth, literally bringing it into the light. The Diogenes of this statuette remains purely a figure of dissent. He has no program to offer and no interest in "progress." At most he stands at the threshold of a philosophical school, by exhorting the viewer to contemplation and exposing the superficiality and "unnaturalness" of conventional life-styles through his own unorthodox behavior. When we find him again, on simple gravestones of the Early Empire, reclining in his cask, he has become nothing more than a memento mori, a symbol of contempt for the world, since death is inescapable.[34]

As we have seen, the retrospective portraits of intellectual heroes of the past arose out of a particular need: they functioned as icons in a unique cult of paideia, even to the point of being actual cult statues in hero shrines. Gradually it seemed the whole of society in urban centers was reading and interpreting the great writers of the past, scholars and orators as well as poets and philosophers. In an age when the structure of individual identity was changing and the inexorable power of Rome loomed on the horizon, these portraits were for the Greeks the principal guardians of their cultural identity. One could see them as a kind of exercise in collective memory in the quest for stability and proper orientation in life. The new cult manifested itself not only in the heroa, but in many branches of education that took in a whole spectrum of both private and collective forms of veneration of the poets and philosophers of the past.[35] Alongside public lectures and

poetic and musical competitions in the gymnasia, there is evidence from the private sphere as well. The appearance of images of the poets and illustrations from their work from the first century on, not only on gemstones and silver vessels, but also on the painted walls of Delian houses and even on humble terra-cotta bowls, gives some idea of the ubiquitous presence of this literary culture in the cultivated home.[36] A good example of this is a silver cup from Herculaneum, probably of Augustan date but employing an earlier motif. The scene is the apotheosis of Homer. The poet is carried aloft by a mighty eagle (as Roman emperors later will be). On either side sit female personifications of the Iliad and Odyssey , who assume a remarkable pose, lost in contemplation, that anticipates the proper attitude of the educated reader.[37]

The attitude toward the intellectual giants of the past is now marked by pious meditation, reverence, and the distance inspired by great awe, in contrast to the public monuments honoring the tragedians in Lycurgan Athens. These new images are bold visions, freed from the bourgeois conventions of contemporary life and retrojected onto an idealized past. At first glance the situation may seem to parallel the glorification of the intellectual hero by the educated bourgeoisie of the late nineteenth century (cf. pp. 6ff.). But Hellenistic readers and devotees were different in genuinely and quite actively seeking guidance for their own lives in the writers of the past. Culture was not some ideal world relegated to a few leisure hours spared from the "real world" of commerce and social interaction. Rather it was the focal point of life as it was lived and the foundation of both personal and collective identity.

The "Gentrification" of the Philosopher Portrait: Carneades and Poseidonius

This new state of affairs must naturally have had some impact on how contemporary intellectuals saw and presented themselves, especially in the philosophical schools of the Late Hellenistic period. Whereas philosopher statues of the third century had posed a challenge to society

Fig. 95

Carneades (ca. 214–128). Bust (now lost) after

an honorific statue ca. 150 B.C. Copenhagen,

Museum of Art. (Cast.)

in their bold indifference to conventional norms and their claim to spiritual leadership, those of later philosophers gradually adapt themselves to these very standards of the bourgeois image. With the growing rivalry between the philosophical schools, the stark contrast in image of earlier times eventually disappears.

When a statue of the celebrated philosopher Carneades was dedicated in the Agora by two Athenian citizens about the middle of the second century or just after (fig. 95), the sculptor took as his model the statue of Chrysippus not far away (fig. 54).[38] Both were depicted seated and giving instruction, turning their concentrated attention to an imaginary interlocutor. The similarity is quite surprising, for Carneades was the head of the revived Platonic Academy, and his own

fame was due not least to his lifelong struggle with the dialectic of Chrysippus. He was supposed to have said of himself. "Without Chrysippus there would have been no Carneades" (D. L. 4.62).

However striking the similarities to the older portrait, there are also differences. Like the standard honorary statues of the day, Carneades wears a chiton under his himation. Toughness and the refusal to succumb to the needs of the body and one's own mortality are no longer a part of the philosopher's message. In place of the careless external appearance and passionately aggressive energy of Chrysippus, we see an elegant figure, with well-groomed beard and a countenance of fine proportions derived from Late Classical art. Yet the strenuously raised furrows of the brow recall at first glance the expressions of the Stoics. If we compare this, however, with the portraits of Zeno, or even Chrysippus (cf. figs. 53, 60), it becomes clear that in Carneades a different kind of thinking is meant: not the vigorous and direct attack on an opponent, but rather a distanced scrutiny and weighing of arguments. Interestingly the contraction of the brows that was so characteristic of third-century portraits is no longer present. Instead, the deep furrows running in "orderly" parallel lines dominate the facial expression. This is a man of contemplation, who listens carefully and calmly formulates his argument. The portrait makes no particular ethical claims.

The fact that the statue quotes from an earlier Hellenistic philosopher portrait seems to be not a special case, but rather symptomatic of a broader trend. By the mid-second century, the great poets and philosophers of the previous century already enjoyed the status of classics. This retrospective tendency, which had informed so much of Hellenistic culture by the middle of the second century, is particularly tangible here. This backward-looking stance is accompanied by a kind of eclecticism, which had the effect of smoothing over any uncomfortable disagreements between philosophical schools. Under these circumstances, it is not so astounding after all if the image of a Stoic is taken as the model for that of the leader of the Academics.

There is yet another way in which the portrait of Carneades differs from that of his predecessor. The long hooked nose and crooked

Fig. 96

Carneades. Roman copy of the period of

the emperor Trajan. Munich, Glyptothek.

mouth, which are well preserved in a new copy in Munich (fig. 96), are striking features of an unmistakable, individual physiognomy. For the first time, a Hellenistic portrait of a philosopher clearly reveals the man himself, as an individual, not merely in his role as the representative of a particular school. Not surprisingly, of all the philosopher statues in Athens, this one made the greatest impression on the young Cicero (Fin. 5.4).

In the course of the second century, philosophers of every stripe were steadily integrated into urban social and political life. A typical example is Athens, which in the year 155 B.C. sent the heads of three philosophical schools, the Stoa, the Peripatos, and the Academy, as envoys to Rome (where Carneades held his famous speeches for and against justice). In 124/3, the polls officially recognized these same three schools as centers of education, and at the funeral of the great

Fig. 97

Stoic philosopher of the late second century

B.C. , perhaps Panaitios (died 109 B.C. ). Roman

copy. Rome, Vatican Museums.

Stoic Panaitios all the philosophers in Athens took part as a corporate entity. There was a reconciliation between Epicureans and Stoics, and some Epicureans even agreed to serve as public magistrates.[39]

Along with this rapprochement of the philosophical schools, it appears that the differentiation of the portraits according to school that had been the norm in the third century, expressed in particular mimetic and physiognomic formulas, gradually disappeared, to make way for a more general look of contemplation. This is the same look, as we shall soon see, to which many citizen portraits of the period also adapt. There are, unfortunately, no securely identified philosopher portraits of the later second century. The portrait of a man with unusually large eyes might be that of a Stoic (fig. 97). The closely shorn but untended beard recalls Chrysippus, while the forehead raised in a gesture of skepticism is closer to Carneades. The portrait is preserver in three

copies found in Rome and must represent a popular figure in Late Hellenistic philosophy. A possible candidate would be Panaitios, who molded out of the classical tradition a straightforward and pragmatic ethical theory well suited to the needs of Roman aristocrats. The style of the portrait would be consistent with a dating toward the end of his life in 109.[40]

The end of this development may be represented by the portrait of Poseidonius of Apamea in Syria (ca. 135–50 B.C. ), created about 70 B.C. (fig. 98). Poseidonius was a pupil of Panaitios and, like him, taught on the island of Rhodes. The portrait is known from only a single copy of superb quality, a bust of early Augustan date.[41] From the preserved portion of the chest we can infer that the figure was standing and clad in chiton and himation, thus no different from standard portrait statues of contemporary Greeks and essentially the same as those of the fourth century B.C. The modest expression no longer betrays him as a philosopher, and certainly not as a Stoic struggling with his thoughts. In fact only the beard signals the philosopher, and it is so closely trimmed as to be barely noticeable. Nevertheless, unlike the beard of the so-called Panaitios, this one has been carefully trimmed. A number of contemporary portraits are known from Rhodes featuring this kind of closely trimmed beard, but it is unlikely that all of them are philosophers. Rather, it must be a kind of "philosopher look" that was fashionable in this university town. The typical citizen image and the would-be philosopher seem, at least on Rhodes, to have become virtually indistinguishable.

Most striking, however, in the portrait of Poseidonius is the self-consciously classicizing quality, which becomes almost oppressive in the "Polyclitan" locks of hair. This is the hallmark of a man who saw it as his primary responsibility to gather the spiritual heritage of the Greeks and pass it on to the Romans who flocked to his lectures. For a man of his eclectic philosophy, there would have been no point in modeling his image after that of Chrysippus. There is nothing left in this portrait of intellectual passion. The quiet, serious features are those of a tenured professor, self-satisfied both with his own methods

Fig. 98

Poseidonius (ca. 135–50 B.C. ). Roman bust after an original

of the philosopher's lifetime. Naples, Museo Nazionale.

and research and with the recognition accorded him by his pupils and by society, a man who identifies fully with the values of that society and has no more interest in changing it.

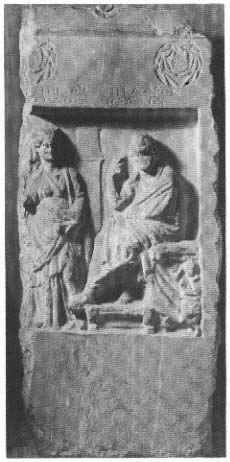

Yet in spite of these changing circumstances, the philosopher remained a figure of great authority in the Late Hellenistic age. His reputation now rested primarily on his role as interpreter of the classical tradition. For example, a certain Hieronymos, active on Rhodes in the second century B.C. , had himself depicted, on the doorway of his funerary naiskos, reading and lecturing to a circle of his pupils. Characteristically, he holds an open book roll from which he reads and interprets the text.[42] The role of interpreter is in turn closely linked to that of the educator and counselor.

This association is well expressed by a relief of the first century B.C. (fig. 99) that has provoked a great deal of interest on account of a mysterious psi-shaped symbol.[43] Underneath the large framed picture (or window?) bearing the enigmatic sign, a philosopher is seated with his family. His portrait, like that of Poseidonius, is patterned after Late Classical models. Although he has no other heroic traits and sits comfortably in a chair, he is shown on a much larger scale than all the other, standing figures. This is presumably a grave monument that a father commissioned for the resident philosopher to whom he had entrusted the education of his three children. The difference in scale is supposed to convey the great awe in which the teacher is held, and the success of his teaching is expressed in the well-bred manners and poses of the children, a young man, a youth, and a girl. The father is characterized by his bald head and realistically rendered face as an unmistakable individual and wears the same outfit as the philosopher and elder son, a himation without a garment beneath it. This is not the current fashion and marks him as an adherent of the philosophical way of life. If we interpret the curious symbol above the philosopher as a psi, it could be a reference to the concern for the peace and security of the soul common to all those depicted here. The intimate ambience of the scene brings to mind the Greek philosophers employed in the households of contemporary Roman aristocrats. But there, no matter how much the Romans valued the company of the philosopher and

Fig. 99

Grave relief (?) of an in-house philosopher with his host family.

First century B.C. Berlin, Staatliche Museen.

relied on his advice in times of spiritual crisis, they would not have accorded him such a position of honor within the family. The relief is thus a particularly impressive testimony to the high status accorded philosophical teaching in the Late Hellenistic world.[44]

The "Intellectualization" of the Citizen Portrait

A brief look at the imagery of the ordinary citizen in Late Hellenistic art will make clear that we are dealing here with a reciprocal process. At the same time that the distinguishing characteristics of the philosopher portrait become less pronounced, citizens of the Greek cities put the emphasis on learning and a contemplative nature in their own self-image. From the second century on, reading and contemplation are

Fig. 100

Portrait of a contemplative citizen, from a

Late Hellenistic funerary or votive monument.

Athens, National Museum.

seen as outstanding values and appropriate motifs for the representation of a male citizen on his tomb monument. It is only against the background of this intellectualization of everyday life that we can understand the place of the retrospective portraits within this cultural system.[45] A number of portraits of the later second century from Delos, Athens, and elsewhere have a markedly contemplative expression. Occasionally a raised brow seems to allude directly to the appearance of Carneades or another philosopher (fig. 100).[46] We have already observed the beginnings of this process of assimilation in the portraiture and grave reliefs of the Late Classical period (cf. pp. 67ff.). Now, however, it becomes much more apparent and is no longer limited to older citizens.

The contemplative expression is, however, often combined with a dramatic turn of the head and other formulas that denote energy

and determination, derived from the repertoire of contemporary ruler portraits. The citizen male evidently sought to portray himself as a combination of philosophical meditation and energetic vitality, or, in more personal terms, a combination of the new intellectual hero of the polis and the dynamic and beneficent monarch. The resulting ambiguity is perhaps reflected in the oddly contradictory appearance of certain heads.[47]

The description of this physiognomy as "contemplative" would be no more than a subjective impression if we did not have other evidence of the central importance of philosophy scholarship, and learning that helps give voice to these "contemplative" men. We have already noted the significance of the gymnasia, as well as the appearance of learned motifs on objects of daily use and even in the painted decoration on the walls of private homes. A particularly valuable testimony is the widespread adoption of the imagery of paideia on the funerary reliefs. These are preserved in large numbers, especially from the cities of Ionia, and provide direct evidence of the way in which a broad stratum of the bourgeoisie wished to see itself represented.[48]

The first thing we notice on these reliefs is the large number of book rolls and writing tablets and implements. These meaningful attributes are displayed on shelves, presented by slaves, and of course also held by the deceased and others. They may belong to youths of school age, to men in the prime of life, or to old men, and even some women are also celebrated in this manner for their paideia . The epigrams accompanying the reliefs confirm that such attributes do refer specifically to the notion of learning and education. The virtues of a "universal" learning are suggested in the plethora of volumes, often depicted in bundles or stored in a case.

In addition to this general praise of learning through the use of attributes, there are also more explicit images, particularly from those cities that have left us the largest number of grave stelai. For example, in Smyrna, Cyzicus, and Delos, it is not unusual for an older man to be depicted as a seated "thinker." His authority may be expressed in his elevated position or in the lavish and dignified chair on which he sits. On a fine stele now in Winchester (fig. 101), a citizen of Smyrna gives instruction looking down from his elevated seat, the fingers of his right hand ticking off the arguments. His face, with its look of

Fig. 101

Grave stele from Smyrna. Second

century B.C. Winchester College.

concentration, is turned not to his wife, but to the viewer. As in the portrait of Chrysippus, the image speaks directly to the viewer. The female figure, as on many of these stelai, stands in casual proximity to the "philosopher," her appearance recalling that of a priestess of Demeter. This suggests that in her role as wife, she is celebrated above all for her piety.[49]

It is no accident that the image of the seated man calls to mind that

Fig. 102

Grave stele of an elderly citizen from Smyrna.

Second century B.C. Leiden, Rijksmuseum.

of Chrysippus (fig. 54). Other stelai as well betray a visual association with well-known statues of poets and philosophers of the third century. Interestingly, the most popular motif is that of meditation with the head propped up on one hand, in the manner of the philosopher in the Palazzo Spada and the bronze statuette of Kleanthes (cf. fig. 58), which has the effect of distancing the thinker from the world outside. A particularly fine example, again from Smyrna, shows an old man with markedly individualized features and the unmistakable expression of a thinker (fig. 102).[50]

Such instance are not, however, deliberate quotations of famous monuments. Rather, the familiar images of mental and intellectual activity created in Early Hellenistic art had simply become ingrained in the popular consciousness, along with their connotations of dignity and authority. That these images were indeed understood as signs of

Fig. 103

Grave stele from Byzantium. First century B.C. Istanbul, Archaeological Museum.

outstanding intellectual ability or achievement is confirmed by the fact that the men so depicted can in many instances be shown to have held an office in the gymnasium.[51]

In the course of the later second and first centuries B.C. , the imagery of paideia becomes widespread in the funerary art of Hellenistic cities. In Byzantium, for example, the venerable image of the "Totenmahl" (funerary banquet) relief is transformed into what we might call a "Bildungsmahl." Tables and shelves are filled not with food, but rather food for thought: book rolls and writing implements. Cultivated gentlemen hold open book rolls instead of drinking vessels, and one even seems to be playing the part of one of the Seven Wise Men, the scholar and astronomer expounding on the globe with his pointer (fig. 103).[52] The familiar look of contemplation here gives him a rather self-satisfied appearance. It is worth noting that this motif of the "Bildungsmahl" seems to appear in Byzantium on the largest and artistically most ambitious grave stelai. It is, in other words, the upper class that so insistently lays claim to the value of learning, even in a city that

at this time was still on the margins of Greek cultural life. At one time, in the third century B.C. , such images, attached to pioneering thinkers, were seen as a challenge to society and to traditional political and social ideas, a harbinger of a new way of thinking. Now the image looks merely blasé, the very essence of acceptable behavior among the established bourgeoisie.

Man the Reader: Paradigm for a New Age

Rudolf Pfeiffer christened the Hellenistic world the "Age of the Book."[53] For Alexandrian philologists and scholars, the new age began under Ptolemy I, but as a broad cultural phenomenon it took time to evolve. By the second century, as we have just observed on the gravestones, books and reading occupied a place of central importance in the life of the average city dweller. Unfortunately we know very little about the actual production and distribution of books in the Hellenistic age. On the basis of papyri found in Egypt, we can say that the number of volumes in circulation was increasing in the Late Hellenistic period but was still far fewer than under the Roman Empire. The buying of books must, however, have been an important part of the whole enterprise of education, for about 100 B.C. the grammarian Artemon of Cassandreia could publish two volumes aimed at an already existing clientele, On the Collecting of Books and On the Use of Books . This marked the founding of a new genre of literature that was to become very popular under the Empire.[54]

The image of the reader was already a part of intellectual iconography in Early Hellenistic art (cf. fig. 71). But at that time reading was only one of many possibilities for expressing a particular form of intellectual activity. By Late Hellenistic times, however, reading seems to have become the very essence of the intellectual process in general. From now on it was no longer possible to imagine an intellectual other than with a book in his hand or sitting nearby. The image was evidently so appealing that it was eventually adopted for the great figures of the past, both poets and philosophers. Plato and Sophocles are both turned into avid readers, and even Homer—apparently undeterred by his blindness—is shown as a bent old man reading from his Iliad

Fig. 104

Homer seated on an altar, reading. Fragment of a Tabula

Iliaca. Augustan (?). Berlin, Staatliche Museen.

on a fragment of a Tabula Iliaca (fig. 104). Even the Cynics, who once despised reading, as also every other form of learning, are turned into readers. Diogenes himself emerges from his barrel book in hand, though first on engraved rings of the Early Roman period. In such instances, the motif does not carry a specific message about the subject but serves only as a general symbol of intellectual activity. The writers of old, it suggests, were also learned men.[55]

Compared to the portraits created in the later third and second centuries, these images of the poet or philosopher as reader represent a surprising standardization and impoverishment of the iconography of the intellectual. That said, we should be careful to bear in mind that we are almost entirely dependent on copies in the minor arts. Nevertheless, the coins that we noted with the type of Homer reading

Fig. 105

So-called Arundel Homer. Bronze head, probably from

the seated statue of a reading figure. First century B.C.

London, British Museum.

(fig. 88c) suggest that we cannot dismiss the reader type as an incidental or occasional phenomenon. It must have been used for major public monuments as well. One such may be represented by the impressive life-size bronze head of a poet reading, a Late Hellenistic work said to come from Istanbul and known as the Arundel Homer (fig. 105).[56]

A small marble relief provides at least some idea of the body. The poet sits in a simple chair, bent over and holding in both hands an unrolled book.

The mature, handsome face is placid and patrician. The uniform, classicizing arrangement of hair and beard concentrates our attention on the subtle movements of the lively brow and the deep-set eyes. The effect is not one of energy or mental strain; rather the artist wanted to convey the passive concentration of the reader in the portrait of a poet. The mouth is open but fully relaxed, as he reads aloud to himself. It is not enough to say that this is just an example of classicistic style and the modulation of expressionism. This is rather the new model of the intellectual. The poet is so lost in his reading that he is oblivious of the world around him. The quiet beauty of his physical features reflects a sense of inner perfection, achieved through total dedication to the classics. When viewed in this light, this work too reveals a didactic aspect.

The reader has become the exemplar of an isolated intellectual existence. Reading is a solitary process that removes the reader from the world around him. He lives instead in the world of the author and communicates only with him instead of in open discussion. In so doing, the reader creates his own private world, distant from the public life of his society. In the following chapter we shall observe how this paradigm came to fruition in Rome and its empire.