Soft Pillows and Softer Poets

Just as Menander (fig. 45) had done, Poseidippus also sits on a noticeably plush cushion. It is possible that this is a specific visual symbol in

the iconography of the poet, based on the idea of a comfortable domestic ambience as the prerequisite to poetic inspiration.

This interpretation suggests itself in spite of the meagre state of our evidence. The statue of the so-called pseudo-Menander, which was found together with that of Poseidippus, likewise shows the poet in a relaxed pose on a backed chair with thick cushion.[56] The same motif is also found in the reliefs depicting Menander mentioned earlier, as well as the famous wall painting in the Casa di Menandro in Pompeii. That the cushion is not restricted to comic poets can be inferred from the statue of the tragic poet Moschion (fourth–third century), though in this case, unlike Menander, Poseidippus, and the pseudo-Menander, he wears a simple mantle without the undergarment, and his chair does not have the backrest.[57] The most impressive example, however, is on the Late Antique diptych in Monza ![]() with a poet and Muse. The poet with shaven head (perhaps of the Late Republic) is seated with legs crossed upon a throne with a particularly luxurious cushion. The book rolls and diptychs strewn on the floor, together with the poet's expression, looking out dreamily into the void, can be taken to express poetic activity.[58] The notion that being a poet is well suited to a comfortable, "private" life-style could well have been widespread even before the Early Hellenistic statues. On a painted grave stele of the mid-fourth century, a certain Hermon sits casually leaning back on a splendid chair with a high back and thick cushion.[59] His literary association is made clear by the large cabinet of book rolls beside him, a rather rare motif at this period.[60] If this observation is correct, then the pillow in the statue of Menander may already be understood as a specific "poet's cushion."

with a poet and Muse. The poet with shaven head (perhaps of the Late Republic) is seated with legs crossed upon a throne with a particularly luxurious cushion. The book rolls and diptychs strewn on the floor, together with the poet's expression, looking out dreamily into the void, can be taken to express poetic activity.[58] The notion that being a poet is well suited to a comfortable, "private" life-style could well have been widespread even before the Early Hellenistic statues. On a painted grave stele of the mid-fourth century, a certain Hermon sits casually leaning back on a splendid chair with a high back and thick cushion.[59] His literary association is made clear by the large cabinet of book rolls beside him, a rather rare motif at this period.[60] If this observation is correct, then the pillow in the statue of Menander may already be understood as a specific "poet's cushion."

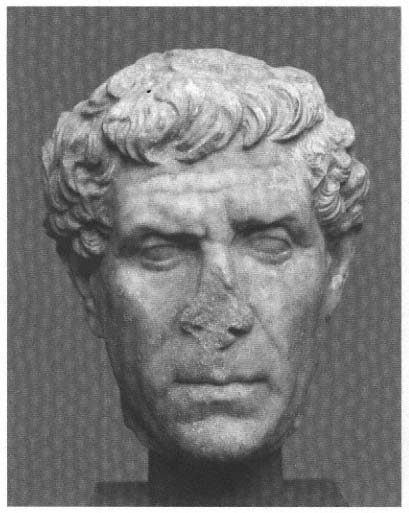

Nevertheless, in the few surviving Hellenistic portraits of poets, at least those whose body is unknown, it is not possible to discern a particular facial expression of a poet, as it is, say, for most third-century philosophers. If, for example, the portrait formerly identified as Vergil did not occur as part of a double herm together with the so-called Hesiod, in one copy wearing an ivy wreath, we would not even be able to recognize him as a poet (fig. 78),[61] for many civilian portraits of the Hellenistic period are marked by a decidedly contemplative quality. In the case of "Vergil," the suggested dating and interpretation

Fig. 78

Portrait of a Hellenistic poet, not yet identified. Roman copy of a statue of

the second century B.C. Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek.

fluctuate between the late third and the first centuries B.C. , between Greek and Roman poets. Stylistic arguments would support a High Hellenistic dating, in the early second century B.C. , but even then will not determine with certainty whether a Greek or a Roman poet is depicted here.

The sculpture was above all trying to convey, as in the case of Poseidippus, intellectual activity in the sense of a restless searching quality, in the powerful but sudden movement of the brow. The expression, which constitutes only one element of the face, is, like that of Poseidippus, almost one of suffering. There is, at any rate, nothing strained or convulsive about it. Mighty mental effort, as we have observed in the Stoics and their associates, is apparently not part of the image of the Hellenistic poet. His work is more dependent on inspiration than on grim perseverance. A striking feature is the full and luxuriant hair, on a man of rather advanced age, perhaps again an allusion to the elegant life-style of the poet.