Bodies, Healthy and Unhealthy

The portrait of Epicurus displays yet another "individual" characteristic. His body, especially those parts of it that are exposed, is rendered as extremely feeble. This is particularly exaggerated in a small statuette in the Palazzo dei Conservatori in Rome (fig. 69).[33] But even in the fine copy of the statue in Naples, the body is flabby and unarticulated in a manner unknown in any other statue type. If the statues of the three philosophers did indeed stand alongside one another in the Kepos, this trait of Epicurus must have been especially noticeable. It is probably meant as a reference to the long, debilitating illness of Epicurus' later years. But again, it is not intended so much as a biographical trait, but rather as a sign of the exemplary and virtuous way of life. The equanimity with which the master not only endured his pain to the end but overcame it through the memory of his earlier happiness

Fig. 69

Small-scale copy of the portrait of Epicurus.

H: 23.5 cm. Rome, Palazzo dei Conservatori.

was much admired by his friends and pupils, who saw him as proof that the truly wise man who follows Epicurus' teachings can attain ataraxia and eudaimonia (peace of mind and happiness) even in the most difficult circumstances (D. L. 10.22).

Metrodorus' relaxed and ample body (fig. 63), on the other hand, looks like the embodiment of a life of pleasure. As we have already observed of the head and masklike face, his body also represents a masculine ideal of Classical art, here expressing well-being, serenity, and conviviality with one's fellow man. The comfortable backed chair on which he sits, like that of Menander and Poseidippus, suggests a pleas-

ant domestic ambience. Metrodorus is completely at ease, leaning back comfortably and placidly looking out. He holds a book roll in his left hand, and the right, drawn back to the body, could have held the edge of his garment. Once again we encounter here the old polis ideal at a time when the polis was long gone. What is particularly significant, however, is that this ideal is now evoked by people whose fulfillment in life can be conceived only in the private sphere. One of Metrodorus' writings bore this revealing title: On the Circumstance That Private Life Leads to Happiness Sooner Than Public (Clem. Al. Strom. 2.21 = II.185 Stahlin).

Just as in Epicurus' own teachings, the statues of his friends and disciples focus on the central goal, the condition of spiritual peace and inner joy. Only the master himself is presented as the pioneering spirit, in fact more as a kind of prophet than as one who teaches his students how to think. In the Kepos, great importance was attached to internalizing the teachings of the master. Epicurus had his pupils learn certain key sayings by heart and memorize them so that they would have them ready to hand at any moment. These sayings of the master, the kyriai doxai, functioned as a kind of catechism (D. L. 10.35,85). Perhaps there is an allusion to this constant memorization in the book rolls in the hands of all three statues, or to pastoral letters of Epicurus, which served the same purpose. Epicurus and Hermarchus pause in their reading, the book roll open, while Metrodorus holds his untied in the right hand, as if he were about to start reading.[34] It is rather striking that it should be the statues of Epicureans that hold the book roll. It cannot be meant simply as a symbol of education, as it will be in later Hellenistic portraiture, since Epicurus explicitly rejected the notion of education for its own sake.

In retrospect, a comparison of the portraits of Epicurus and his two kathegemones with those of Chrysippus and the other mighty thinkers reveals that the former must have had a different purpose. The great teachers are presented as exemplars who have already attained the goal. They are both a reminder and an admonition to succeeding generations. This portrayal is in accord with what we may conjecture about the statues' function in the Kepos, where friends and pupils regularly gathered for ceremonies in memory of Epicurus, Metrodorus, and

members of Epicurus' family perhaps in front of the mnema mentioned earlier. The whole calendar of the Epicurean year was organized around these memorial services, at which they would read from the works of the great teachers. In later times, we have evidence for an actual cult of the Epicureans, complete with icons:[35] "They carry around [painted] portraits [vultus ] of Epicurus and even take them into their bedrooms. On his birthday they make sacrifices and always celebrate on the twentieth of the month, which they call eikas —those same people who, so long as they are alive, insist that they do not want to be noticed" (Pliny HN 35.5). In the context of such rituals, the portraits served as a memorial and an honor, as well as an inspiration to follow in their path.

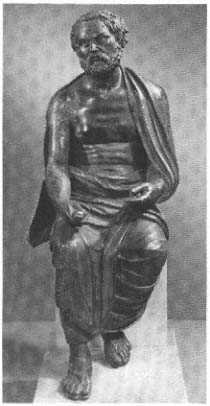

A statuette of the first century B.C. confronts us with a very different image of an Epicurean (fig. 70). If only the head were preserved, with its carefully tended hair and beard, and the contented expression similar to that of Metrodorus, we might well be tempted to identify him as one of the third-century Epicureans. But the proudly displayed fat belly and the uninhibited self-satisfied demeanor, recalling the statue of the Cynic in the Capitoline (cf. fig. 72), suggest that this is not a portrait statue at all, but rather a genre figure, a typical Epicurean. We may be reminded of the type that Horace had in mind, in his ironic characterization of himself:

As for me, when you want a laugh, you will find me in

fine fettle, fat and sleek, a hog from Epicurus' herd.

(Epist. I.4.15f)

This is evidently the image that many people outside the Kepos had of the typical Epicurean: a prosperous bon vivant, always carrying with him the sayings of the master. At least this was the case by the time of Horace, after the popular stereotype had established itself, thanks mainly to New Comedy, that the Epicurean principle of pleasure applied mostly to eating and drinking (fig. 70).[36] The statuette's portrayal of the old hedonist is not marked by genuine mockery, only gentle bemusement, He is indeed a sympathetic figure. This interpre-

Fig. 70

Furniture attachment with statuette of a

"typical" Epicurean. First century B.C. H: 25.5 cm.

New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

tation is also implied in the statuette's original function, for it was the crowning element of a candelabrum that took the form of a column, like those used as table supports. The Ionic capital has two hooks from which lamps could be hung. Thus the jolly old man was visible mainly at symposia. This is a work of exceptional charm, in both style and

iconography, that succeeds in an eclectic combination of contradictory elements in the imagery of the philosopher.[37]

This statuette is a reminder that almost all preserved portraits of the Classical and Hellenistic periods are witnesses to the manner in which the subject understood and wished to present himself. We learn from them a great deal about the image that these intellectuals wanted to project, but as a rule little about how their contemporaries outside their own circle saw them, or to what extent the popular image matched the self-conscious one expressed in the official portraits. One would like to suppose that there had been earlier images that made fun of the all-too-serious thinkers. The statue types that happen to be preserved in Roman copies most likely represent only a small sampling of the variety of images of intellectuals of the Early Hellenistic age. We have, for example, no certainly identified portrait of a third-century Academic or Peripatetic. Surely there continued to be philosophers who clung to the traditional citizen style, such as the long-bearded philosopher on the familiar frescoes from Boscoreale, leaning on a knotty staff in the Classical manner.[38] Furthermore, not all the famous teachers and thinkers were depicted seated, as one might think. For example, the well-known bronze head of an intense philosopher from the Antikythera shipwreck, whose expression and manner recall the portrait of Chrysippus, belonged to a standing statue with the right hand raised in a rhetorical gesture.[39] Stance and pose were presumably no less varied than facial expression.

Another type that seems to have been particularly important was that of the reader, which we have already met in the statue of Metrodorus (fig. 63). Even outside the Kepos, this was already a standard part of the repertoire for representing the intellectual in Early Hellenistic art. Schefold has called attention to two statuettes and suggested identifications for these two as the Academic philosophers Krantor of Soloi and Arkesilaos, probably because the Academics early on turned to the interpretation of Plato's works, and because they were generally reputed to be great readers (D. L. 4.26, 5.31f.).[40] (The story is told of Arkesilaos that he could not go to bed at night without having first read a few pages of Homer, "and in the early morning, when he

Fig. 71

Portrait of a man reading. Bronze statuette after

an original of the third century B.C. H: 27.5 cm.

Paris, Cabinet des Médailles.

wanted to read Homer, he used to say that he was going to see his lover" [D. L. 4.31]. Unfortunately, this is not sufficient grounds for an identification!)

The intellectual depicted in the statuette from Montorio (fig. 71) gestures with his left hand toward the book roll that he holds in his right, like one who is about to begin reading. The left arm is enveloped in the cloak, like that of other seated statues, yet it is captured in

a momentary movement. This is probably meant to suggest the start of a session of reading, "reaching for a book." The head, turned to the side in a contemplative gesture and looking up, would also suit this context. He could scarcely be a philosopher giving instruction, for that entails a gesture of the right hand. Perhaps he is meant to represent a philologist. An interesting life-size seated statue in the Louvre, also derived from an original of the third century, must also have depicted a reader, to judge from the bent-forward position of the upper body and the arms.[41] Particularly noticeable is the casual pose, recalling that of Poseidippus (cf. fig. 75): yet another way of expressing concentration. In the well-known philosopher statue from the Ludovisi Collection, now in Copenhagen,[42] at one time associated with a portrait of Socrates, the figure of the reader acquires an almost exemplary quality through its very high placement and deliberate frontality. The original from which this statue derives probably belongs to the mid-second century, a period in which the motif of reading was of interest not as a process to be physically rendered, but rather as a paradigm for the educated man.